4 Muscular Strength and Endurance

Objectives:

- Describe muscular structure and function

- Identify types of muscles

- Describe an effective resistance exercise program

- Assess your muscular strength and endurance

- Understand the dangers of supplements

Muscular Physiology

Muscles are highly specialized to contract forcefully. Muscles are powered by muscle cells, which contract individually within a muscle to generate force. This force is needed to create movement.

There are over 600 muscles in the human body; they are responsible for every movement we make, from pumping blood through the heart and moving food through the digestive system, to blinking and chewing. Without muscle cells, we would be unable to stand, walk, talk, or perform everyday tasks.

Muscles are used for movement in the body. The largest portion of energy expenditure in the body happens in muscles while helping us perform daily activities with ease and improving our wellness.

Muscular strength is the amount of force that a muscle can produce one time at a maximal effort, and muscular endurance is the ability to repeat a movement over an extended period of time. Resistance training is the method of developing muscular strength and muscular endurance, which in turns improves wellness. This chapter explores many ways to resistance train. However, achieving the best muscular performance requires the assistance of a trained professional.

For more information on muscular fitness and endurance, please click on the link below:

Muscular Strength and Endurance

Types of Muscle

There are three types of muscle:

- Skeletal Muscle

Responsible for body movement.

- Cardiac Muscle

Responsible for the contraction of the heart.

- Smooth Muscle

Responsible for many tasks, including movement of food along intestines, enlargement and contraction of blood vessels, size of pupils, and many other contractions.

Skeletal Muscle Structure and Function

Skeletal muscles are attached to the skeleton and are responsible for the movement of our limbs, torso, and head. They are under conscious control, which means that we can consciously choose to contract a muscle and can regulate how strong the contraction actually is. Skeletal muscles are made up of a number

of muscle fibers. Each muscle fiber is an individual muscle cell and may be anywhere from 1 mm to 4 cm in length. When we choose to contract a muscle fiber—for instance we contract our bicep to bend our arm upwards—a signal is sent from our brain via the spinal cord to the muscle. This signals the muscle fibers to contract. Each nerve will control a certain number of muscle fibers. The nerve and the fibers it controls are called a motor unit. Only a small number of muscle fibers will contract to bend one of our limbs, but if we wish to lift a heavy weight then many more muscles fibers will be recruited to perform the action. This is called muscle fiber recruitment.

Each muscle fiber is surrounded by connective tissue called an external lamina. A group of muscle fibers are encased within more connective tissue called the endomysium. The group of muscle fibers and the endomysium are surrounded by more connective tissue called the perimysium. A group of muscle fibers surrounded by the perimysium is called a muscle fasciculus. A muscle is made up of many muscle fasciculi, which are surrounded by a thick collagenous layer of connective tissue called the epimysium. The epimysium covers the whole surface of the muscle.

Muscle fibers also contain many mitochondria, which are energy powerhouses that are responsible for the aerobic production of energy molecules, or ATP molecules. Muscle fibers also contain glycogen granules as a stored energy source, and myofibrils, which are threadlike structures running the length of the muscle fiber. Myofibrils are made up of two types of protein: Actin myofilaments, and myosin myofilaments. The actin and myosin filaments form the contractile part of the muscle, which is called the sarcomere. Myosin filaments are thick and dark when compared with actin filaments, which are much thinner and lighter in appearance. The actin and myosin filaments lie on top of one another; it is this arrangement of the filaments that gives muscle its striated or striped appearance.

When groups of actin and myosin filaments are bound together by connective tissue they make the myofibrils. When groups of myofibrils are bound together by connective tissue, they make up muscle fibers.

The ends of the muscle connect to bone through a tendon. The muscle is connected to two bones in order to allow movement to occur through a joint. When a muscle contracts, only one of these bones will move. The point where the muscle is attached to a bone that moves is called the insertion. The point where the muscle is attached to a bone that remains in a fixed position is called the origin.

How Muscles Contract

Muscles are believed to contract through a process called the Sliding Filament Theory. In this theory, the muscles contract when actin filaments slide over myosin filaments resulting in a shortening of the length of the sarcomeres, and hence, a shortening of the muscle fibers. During this process the actin and myosin filaments do not change length when muscles contract, but instead they slide past each other.

During this process the muscle fiber becomes shorter and fatter in appearance. As a number of muscle fibers shorten at the same time, the whole muscle contracts and causes the tendon to pull on the bone it attaches too. This creates movement that occurs at the point of insertion.

For the muscle to return to normal (i.e., to lengthen), a force must be applied to the muscle to cause the muscle fibers to lengthen. This force can be due to gravity or due to the contraction of an opposing muscle group.

Skeletal muscles contract in response to an electric signal called an action potential.

Action potentials are conducted along nerve cells before reaching the muscle fibers. The nerve cells regulate the function of skeletal muscles by controlling the number of action potentials that are produced. The action potentials trigger a series of chemical reactions that result in the contraction of a muscle.

When a nerve impulse stimulates a motor unit within a muscle, all of the muscle fibers controlled by that motor unit will contract. When stimulated, these muscle fibers contract on an all-or-nothing basis. The all- or-nothing principle means that muscle fibers either contract maximally along their length or not at all. Therefore, when stimulated, muscle fibers contract to their maximum level and when not stimulated there is no contraction. In this way, the force generated by a muscle is not regulated by the level of contraction by individual fibers, but rather it is due to the number of muscle fibers that are recruited to contract. This is called muscle fiber recruitment. When lifting a light object, such as a book, only a small number of muscle fibers will be recruited. However, those that are recruited will contract to their maximum level. When lifting a heavier weight, many more muscle fibers will be recruited to contract maximally.

When one muscle contracts, another opposing muscle will relax. In this way, muscles are arranged in pairs. An example is when you bend your arm at the elbow: you contract your bicep muscle and relax your tricep muscle. This is the same for every movement in the body. There will always be one contracting muscle and one relaxing muscle. If you take a moment to think about these simple movements, it will soon become obvious that unless the opposing muscle is relaxed, it will have a negative effect on the force generated by the contracting muscle.

A muscle that contracts, and is the main muscle group responsible for the movement, is called the agonist or prime mover. The muscle that relaxes is called the antagonist. One of the effects that regular strength training has is an improvement in the level of relaxation that occurs in the opposing muscle group.

Although the agonist/antagonist relationship changes, depending on which muscle is responsible for the movement, every muscle group has an opposing muscle group.

Below are examples of agonist and antagonist muscle group pairings:

|

AGONIST(Prime Mover) |

Antagonist |

|

Latimus Dorsi (upper back) |

Deltoids (shoulder) |

|

Rectus Abdominus (stomach) |

Erector Spinae (back muscles) |

|

Quadricepts (top of thigh) |

Hamstrings (back of thigh) |

|

Gastrocnemius (calf) |

Tibialis Anterior (front of lower leg) |

|

Soleus (below calf) |

Tibialis Anterior (front of lower leg) |

Smaller muscles may also assist the agonist during a particular movement. The smaller muscle is called the synergist. An example of a synergist would be the deltoid (shoulder) muscle during a press-up. The front of the deltoid provides additional force during the press-up; however, most of the force is applied by the pectoralis major (chest). Other muscle groups may also assist the movement by helping to maintain a fixed posture and prevent unwanted movement. These muscle groups are called fixators. An example of a fixator is the shoulder muscle during a bicep curl or tricep extension.

Types of Muscular Contraction

- Isometric

This is a static contraction where the length of the muscle, or the joint angle, does not change. An example is pushing against a stationary object such as a wall. This type of contraction is known to lead to rapid rises in blood pressure.

- Isotonic

This is a moving contraction, also known as dynamic contraction. During this contraction the muscle fattens, and there is movement at the joint.

Types of Isotonic Contraction

- Concentric

This is when the muscle contracts and shortens against a resistance. This may be referred to as the lifting or positive phase. An example would be the lifting phase of the bicep curl.

- Eccentric

This occurs when the muscle is still contracting and lengthening at the same time. This may be referred to as the lowering or negative phase.

Muscle Fiber Types

Not all muscle fibers are the same. In fact, there are two main types of muscle fiber:

- Type I

Often called slow-twitch or highly- oxidative muscle fibers

- Type II

Often called fast-twitch or low- oxidative muscle fibers

Additionally, Type II muscle fibers can be further split into Type II A and Type II B.

Type II b fibers are the truly fast twitch fibers, whereas Type II a are in between slow and fast twitch. Surprisingly, the characteristics of Type II a fibers can be strongly influenced by the type of training undertaken. Following a period of endurance training, they will start to strongly resemble Type I fibers, but following a period of strength training they will start to strongly resemble Type II b fibers. In fact, following several years of endurance training they may end up being almost identical to slow-twitch muscle fibers.

Type I (Slow-Twitch Muscle Fibers)

Slow-twitch muscle fibers contain more mitochondria, the organelles that produce aerobic energy. They are also smaller, have better blood supply, contract more slowly, and are more fatigue resistant than their fast-twitch brothers. Slow-twitch muscle fibers produce energy, primarily, through aerobic metabolism of fats and carbohydrates. The accelerated rate of aerobic metabolism is enhanced by the large numbers of mitochondria and the enhanced blood supply. They also contain large amounts of myoglobin, a pigment similar to hemoglobin that also stores oxygen. The myoglobin provides an additional store of oxygen for when oxygen supply is limited. This extra oxygen, along with the slow-twitch muscle fibers’ slow rate of contraction, increases their endurance capacity and enhances their fatigue resistance. Slow-twitch muscle fibers are recruited during continuous exercise at low to moderate levels.

Type IIb (Fast-Twitch Low-oxidative Muscle Fibers)

These fibers are larger in size, have a decreased blood supply, have smaller mitochondria and less of them, contract more rapidly, and are more adapted to produce energy anaerobically (without the need for oxygen) than slow-twitch muscle fibers. Their reduced rate of blood supply, together with their larger size and fewer mitochondria, makes them less able to produce energy aerobically, and are therefore, not well suited to prolonged exercise. However, their faster rate of contraction, greater levels of glycogen, and ability to produce much greater amounts of energy anaerobically make them much more suited to short bursts of energy.

Because of their greater speed of contraction and reduced blood supply, they are far less fatigue resistant than slow- twitch fibers, and they tire quickly during exercise.

Numbers of Slow and Fast-Twitch Fibers

The number of slow and fast-twitch fibers contained in the body varies greatly between individuals and is determined by a person’s genetics. People who do well at endurance sports tend to have a higher number of slow-twitch fibers, whereas people who are better at sprint events tend to have higher numbers of fast-twitch muscle fibers. Both the slow twitch and fast-twitch fibers can be influenced by training. It is possible through sprint training to improve the power generated by slow twitch fibers, and through endurance training, it is possible to increase the endurance level of fast-twitch fibers. The level of improvement varies, depending on the individual, and training can never make slow-twitch fibers as powerful as fast- twitch, nor can training make fast-twitch fibers as fatigue resistant as slow-twitch fibers.

Cardiac Muscle Structure and Function

Cardiac muscle cells are only found in the heart. They are elongated and contain actin and myosin filaments, which form sarcomeres; these join end to end to form myofibrils. The actin and myosin filaments give cardiac muscle a striated appearance. The striations are less numerous than in skeletal muscle. Cardiac muscles contain high numbers of mitochondria, which produce energy through aerobic metabolism. An extensive capillary network of tiny blood vessels supply oxygen to the cardiac muscle cells. Unlike the skeletal muscle cells, the cardiac cells all work as one unit, all contracting at the same time. In short, the sinoatrial node at the top of the heart sends an impulse to the atrioventricular node, which sends a wave of polarization that travels from one heart cell to another causing them all to contract at the same time.

Smooth Muscle Structure and Function

Smooth muscle cells are variable in function and perform numerous roles within the body. They are spindle shaped and smaller than skeletal muscle and contain fewer actin and myosin filaments. The actin and myosin filaments are not organized into sarcomeres, so smooth muscles do not have a striated appearance. Unlike other muscle types, smooth muscle can apply a constant tension. This is called smooth muscle tone. Smooth muscle cells have a similar metabolism to skeletal muscle, producing most of their energy aerobically. As such, they are not well adapted to producing energy anaerobically.1

Resistance Exercise Programing

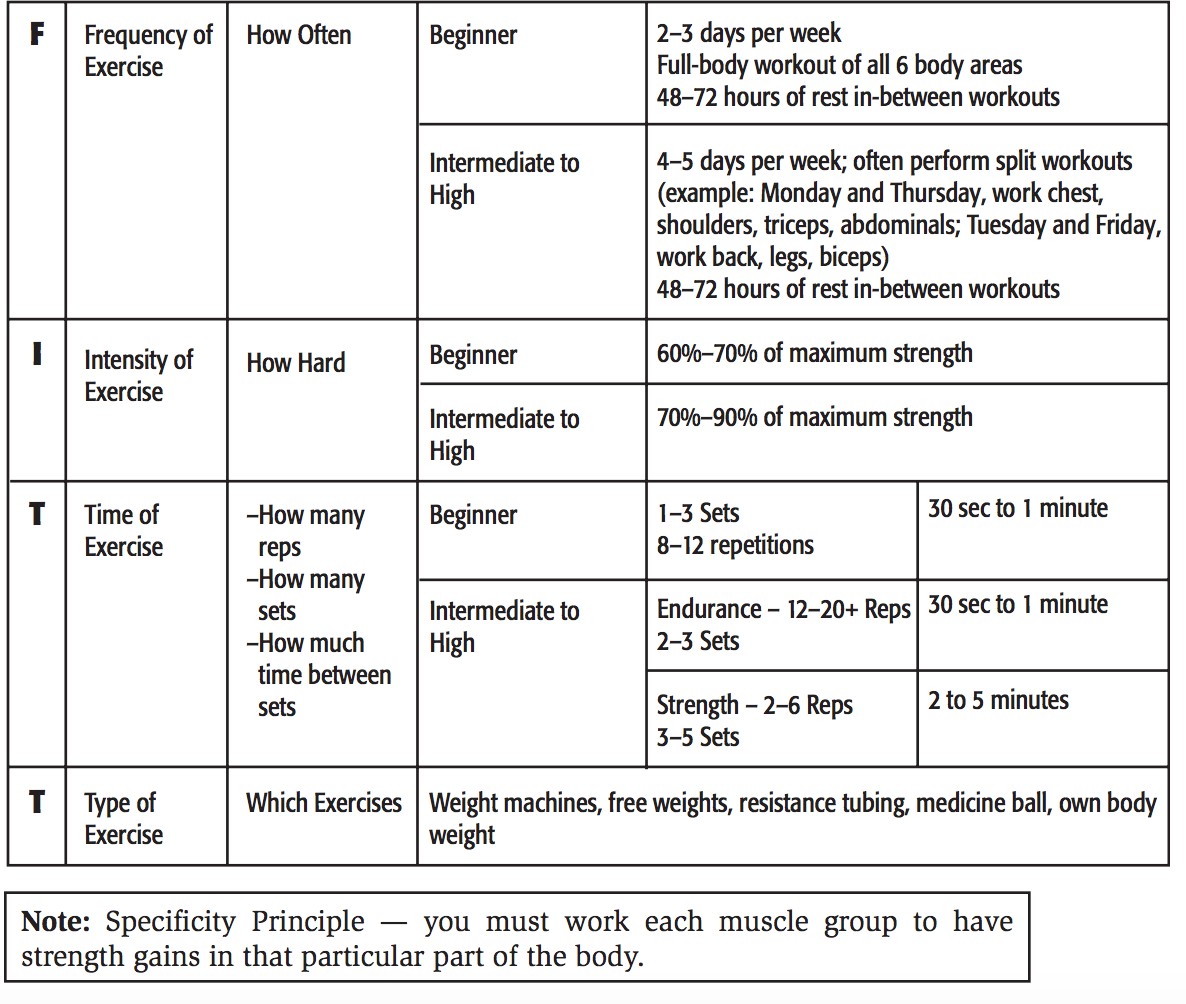

Designing a resistance exercise program can seem like a daunting task. However, the basics are very simple. The table below provides instructions for designing an effective resistance exercise program.

Resistance Exercise Program

Recommendations for Resistance Training Exercise

- Perform a minimum of 8 to 10 exercises that train the major muscle groups.

- Workouts should not be too long. Programs longer than one hour are associated with higher dropout rates.

- Choose more compound, or multi-joint exercises, which involve more muscles with fewer exercises.

- Perform one set of 8 to 12 repetitions to the point of volitional fatigue.

- More sets may elicit slightly greater strength gains, but additional improvement is relatively small.

- Perform exercises at least 2 days per week.

- More frequent training may elicit slightly greater strength gains, but additional improvement is relatively small since progress is made during the recuperation between workouts.

- Adhere as closely as possible to the specific exercise techniques.

- Perform exercises through a full range of motion.

- Elderly trainees should perform the exercises in the maximum range of motion that does not elicit pain or discomfort.

- Perform exercises in a controlled manner.

- Maintain a normal breathing pattern.

- If possible, exercise with a training partner.

- Partners can provide feedback, assistance, and motivation.

Position Stand on Progression Models in Resistance Training for Healthy Adults2

- Both concentric and eccentric muscle actions

- Both single and multiple joint exercises

- Exercise sequence

- large before small muscle group exercises

- multiple-joint exercises before single-joint exercises

- higher intensity before lower intensity exercises

- When training at a specific RM load

- 2-10% increase in load if one to two repetitions over the desired number

- Training frequency

- 2-3 days per week for novice and intermediate training

- 4-5 days per week for advanced training

- Novice training

- 8-12 repetition maximum (RM)

- Intermediate to advanced training

- 1-12 RM using periodization* (strategic implementation of specific training phases alternating between phases of stress and phases of rest)

- eventual emphasis on heavy loading (1-6 RM)

- at least 3-min rest periods between sets

- moderate contraction velocity

- 1-2 s concentric, 1-2 s eccentric

- Hypertrophy training

- 1-12 RM in periodized fashion, with emphasis on the 6-12 RM zone

- 1- to 2-min rest periods between sets

- moderate contraction velocity

- higher volume, multiple-set programs

- Power training (two general loading strategies):

Strength training

- use of light loads

- 30-60% of 1 RM

- fast contraction velocity

- 2-3 min of rest between sets for multiple sets per exercise

- emphasize multiple-joint exercises especially those involving the total body

Local muscular endurance training

- light to moderate loads

- 40-60% of 1 RM

- high repetitions (> 15)

- short rest periods (< 90 seconds)

Recommendations should be viewed within the context of an individual’s target goals, physical capacity, and training status.

Six Types of Resistance Training

Each type of resistance training benefits muscles in a different way. While these types of resistance training are not new, they could be unique sources of resistance that you have not considered in your quest to add muscle to your frame. Using these forms of resistance alone, in combination with one another, or in combination with the more traditional resistance apparatus, can enable you to diversify your efforts to produce valuable and improved results.

In each type of training, you may use an apparatus to create an environment for resistance. The uniqueness of these sources is found in the way they are implemented. You might use a dumbbell for a particular exercise in some of these alternative resistance methods, but the way you use the resistance through a range of motion may be altogether different.

- Dynamic Constant Training

As the name suggests, the most distinctive feature of dynamic constant training (DCT) is that the resistance is constant. A good example of DCT occurs when you use free weights or machines that do not alter resistance, but redirect it instead. The emphasis shifts to different planes along the muscle group being worked. When you work on a shoulder-press machine, for example, the resistance remains constant over the entire range of motion. It is identical from the bottom of the movement to the top and back down again. Only the direction of the resistance varies.

The resistance redirects itself through the arc and then redirects itself again when the shoulders let the weight come back down to the starting position.

- Dynamic Progressive Training In dynamic progressive training (DPT), resistance increases

progressively as you continue to exercise. DPT is often used as a rehabilitative measure and offers the sort of resistance that builds gradually while remaining completely within the control of the person using it. Equipment includes rubber bands and tubing, springs, and an apparatus controlled by spring-loaded parts. They are low- cost items that are easily accessible and can be used anywhere. Though commonly employed for rehabilitation of torn ligaments, joints, muscles, and broken bones, it is also convenient for travelers on either vacation or business trips.

When combined with traditional forms of resistance, this training creates a better-balanced program and provides the muscles with a welcome alternative from time to time.

- Dynamic Variable Training

This form of resistance exercise takes up where dynamic constant training leaves off. Whereas DCT employs constant resistance, never varying to accommodate the body’s mechanics, DVT can be adapted to the varying degrees of strength of a muscle group throughout a range of motion. Though very few machines succeed in this goal, a few have come close.

Hammer Strength equipment emphasizes common fixed areas of resistance. However, the Strive line of equipment has been able to give the user much more choice in resistance levels during an exercise. Strive equipment uses the DVT principle most effectively because it allows the user to increase resistance at the beginning, middle or end of the range of motion. If your joints are stronger at the end of a movement (the top) or the beginning (the bottom), you can set the resistance accordingly. The Strive line is the most flexible yet of all gym equipment designed to adhere to the DVT principle. It lets you tailor-make your workouts based on your body’s mechanics.

- Isokinetic Training

In isokinetic training (IKT), the muscle is contracted at a constant tempo. Speed determines the nature of this resistance training, not the resistance itself; however, the training is based on movement carried out during a condition of resistance. IKT can be performed with the body’s own weight.

In isokinetic training, resistance is steady while velocity remains constant. For example, isokinetics are at work with any machine that is hydraulically operated. The opposing forces mirror each other throughout the range of motion. A good example would be pressing down for triceps on a hydraulic machine and having to immediately pull up (the resistance is constant in both directions) into a biceps curl while maintaining the same speed. IKT often involves opposing body parts. Trainers can use a variety of apparatus with their clients to achieve isokinetic stasis between muscle groups.

- Isometric Training

Familiar to most people, isometric training (IMT) is an excellent way to build strength with little adverse effect on joints and tendons commonly associated with strength training and lifting heavy weights. Though it appears simple in comparison to traditional resistance training, IMT should not be underrated in its effectiveness. IMT is a method in which the force of contraction is equal to the force of resistance. The muscle neither lengthens nor shortens. You may be wondering how any training occurs without lengthening and shortening the muscles. In IMT, the muscles act against each other or against an immovable object.

Isometric training is what you see swimmers do when they press their hands against a solid wall, forcing all their bodyweight into the wall.

Another common IMT exercise is pressing the hands together to strengthen the pectorals and biceps. Pressing against the wall can involve muscles in the front deltoid, chest and biceps. Isometric training has been proven very effective for gaining strength, but this method usually strengthens only the muscles at the point of the isometric contraction. If the greatest resistance and force are acting upon the mid-portion of the biceps, that is where most of the benefit will occur. A comprehensive isometric routine can serve to increase strength in certain body parts.

- Isotonic Training

This method demands constant tension, typically with free weights. Though this approach may sound a lot like dynamic constant training, it differs because it does not necessarily redirect the resistance through a range of motion, but rather, keeps tension constant as in the negative portion of an exercise. Complete immobility of the muscle being worked is required. For example, in the preacher curl, the biceps are fixed against the bench. They lift (positive), then release the weight slowly downward (negative), keeping the same tension on the muscles in both directions. This is one reason that free-weight exercise is considered the best form of isotonic training. Merely lifting a dumbbell or barbell, however, is not necessarily enough to qualify as isotonic. The true essence of isotonic training is keeping resistance constant in both the positive and negative portions of each repetition.

Exercise Order for Resistance Training

The general guidelines for exercise order when training all major muscle groups in a workout is as follows:

- Large muscle group exercises (i.e., squat) should be performed before smaller muscle group exercises (i.e., shoulder press).

- Multiple-joint exercises should be performed before single-joint exercises.

- For power training, total body exercises (from most to least complex) should be performed before basic strength exercises. For example, the most complex exercises are the snatch (because the bar must be moved the greatest distance) and related lifts, followed by cleans and presses. These take precedence over exercises such as the bench press and squat.

- Alternating between upper and lower body exercises or opposing (agonist–antagonist relationship) exercises can allow some muscles to rest while the opposite muscle groups are trained. This sequencing strategy is beneficial for maintaining high training intensities and targeting repetition numbers.

- Some exercises that target different muscle groups can be staggered between sets of other exercises to increase workout efficiency. For example, a trunk exercise can be performed between sets of the bench press. Because different muscle groups are stressed, no additional fatigue would be induced prior to performing the bench press. This is especially effective when long rest intervals are used.3

Resistance Training Conclusion

The most effective type of resistance- training routine employs a variety of techniques to create a workout program that is complete and runs the gamut, from basic to specialized. Learning different methods of training, different types of resistance, and the recommended order can help you acquire a balanced, complete physique. That does not mean that these training methods will help everybody to win competitions, but they will help you learn how to tune in to your body and understand its functions through resistance and movement. This knowledge and understanding develops a valuable skill, allowing you to become more adept at finding what works best for you on any given day.

Supplements

Many active people use nutritional supplements and drugs in the quest for improved performance and appearance. Most of these substances are ineffective and expensive, and many are dangerous. A balanced diet should be your primary nutritional strategy.

References

1Information pulled from www.strengthandfitnessuk.com

2(ACSM 2002)

3Information is from the National Strength and Conditioning Association and LiveStrong.org

Bringing Together Top Strength and Fitness Professionals. (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2017, from https://www.nsca.com/

Home. (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2017, from https://www.livestrong.org/

Kraemer, W. J., Adams, K., Cafarelli, E., Dudley, G. A., Dooly, C., Feigenbaum, M. S., . . .

American, M. E. (2002, February).

American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Retrieved April 25, 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11828249

N. (n.d.). Strength And Fitness UK. Retrieved April 25, 2017, from http://www.strengthandfitnessuk.com/

Assessing your Muscular Strength and Endurance

Functional Leg Strength Tests

The following tests assess functional leg strength using squats. Most people do squats improperly, increasing their risk of knee and back pain. Before you add weight- bearing squats to your weight-training program, you should determine your functional leg strength, check your ability to squat properly, and give yourself a chance to master squatting movements. The following leg strength tests will help you in each of these areas.

These tests are progressively more difficult, so do not move on to the next test until you have scored at least a 3 on the current test. On each test, give yourself a rating of 0, 1, 3, or 5, as described in the instructions that follow the last test.

Chair Squat

Instructions

- Sit up straight in a chair with your back resting against the backrest and your arms at your sides. Your feet should be placed more that shoulder-width apart so that you can get them under your body.

- Begin the motion of rising out of the chair by flexing (bending) at the hips-not the back. Then squat up using a hip hinge movement (no spine movement). Stand without rocking forward, bending your back, or using external support, and keep your head in a neutral position.

- Return to the sitting position while maintaining a straight back and keeping your weight centered over your feet. Your thighs should abduct (spread) as you sit back in the chair. Use your rear hip and thigh muscles as much as possible as you sit.

Do five repetitions.

Your rating

Un-weighted Squat

Instructions

- Stand with your feet placed slightly more than shoulder-width apart, toes pointed out slightly, hands on hips or across your chest, head neutral, and back straight. Center your weight over your arches or slightly behind.

- Squat down, keeping your weight centered over your arches and actively flexing (bending) your hips until your legs break parallel. During the movement, keep your back straight, shoulders back, and chest out, and let your thighs part to the side so that you are squatting between your legs.

- Push back up to the starting position, hinging at the hips and not with the spine, maximizing a straight back and neutral head position.

Do five repetitions.

Your rating

Single-Leg Lunge-Squat with Rear-Foot Support

Instructions

- Stand about 3 feet in front of a bench (with your back to the bench).

- Place the instep of your left foot on the bench, and put most of your weight on your right let (your left leg should be bent), with your hands at your sides.

- Squat on your right leg until your thigh is parallel with the floor. Keep your back straight, chest up, shoulders back, and head neutral.

- Return to the starting position.

Do three repetitions for each leg.

Your rating:

Rating Your Functional Leg Strength Test Results

- 5 POINTS

Performed the exercise properly with good back and thigh position, weight centered over the middle or rear of the foot, chest out, and shoulders back; good use of hip muscles on the way down and on the way up, with head in a neutral position throughout the movement; maintained good form during all repetitions; abducted )spread) the thighs on the way down during chair squats and double-leg squats; for single-let exercises, showed good strength on both sides; for single-leg lunge-squat with rear-foot support, maintained straight back, and knees stayed behind toes.

- 3 POINTS:

Weight was forward on the toes, with some rounding of the back; used thigh muscles excessively, with little use of hip muscles; head and chest were too far forward; showed little abduction of the thighs during double-leg squats; when going down for single-leg exercises, one side was stronger than the other; form deteriorated with repetitions; for single-leg lunge-squat with rear-foot support and single-leg squat from a bench, could not reach parallel (thigh parallel with floor).

- 1 POINT

Had difficulty performing the movement, rocking forward and rounding back badly; used thigh muscles excessively, with little use of hip muscles on the way up or on the way down; chest and head were forward; on un-weighted squats, had difficulty reaching parallel; and showed little abduction of the thighs on single-leg exercises, one leg was markedly stronger than the other; could not perform multiple repetitions.

- 0 POINTS

Could not perform exercise.

Using Your Results

Are you at all surprised by your rating for muscular strength?

What factors , if any, influenced your ability to perform these assessments?

Are you satisfied with your current level of muscular strength as evidenced in your daily life? For example, are you happy with your ability to lift objects, climb stairs, and engage in sports and recreational activities?

Muscle Endurance Assessment

For best results, do not do any strenuous weight training within 48 hours of any test.

The 60-Second Sit-Up Test

- Equipment

- Stopwatch, clock, or watch with a second hand

- Partner

To prepare, try a few sit-ups to get used to the proper technique and warm up your abdominal muscles.

- Lie flat on your back on the floor with knees bent, feet flat on the floor, and your fingers interlocked behind your neck and your elbows wide. Your partner should hold your ankles firmly so that your feet stay on the floor as you do the sit-ups.

- When your partner signals you to begin, raise your head and chest off the floor until your chest touches your knees or thighs, keeping your elbows wide, then return to the starting position. Keep your neck neutral. Do not force your neck forward, and stop if you feel any pain.

- Perform as many sit-ups as you can in 60 seconds.

Number of sit-ups:

To rank your results, please see the chart on page 16.

WARNING: DO NOT TAKE THIS TEST IF YOU SUFFER FROM LOW-BACK PAIN.

Ratings for 60-second Sit-up Test:

|

Number of Sit-Ups |

||||||

|

Men |

Very Poor |

Poor |

Fair |

Good |

Excellent |

Superior |

|

Age:Under 20 |

Below 36 |

36 – 40 |

41 -46 |

47 – 50 |

51 – 61 |

Above 61 |

|

20 – 29 |

Below 33 |

33 -37 |

38 – 41 |

42 – 46 |

47 – 54 |

Above 54 |

|

30 – 39 |

Below 30 |

30 – 34 |

35 – 38 |

39 – 42 |

43 – 50 |

Above 50 |

|

40 – 49 |

Below 24 |

24 – 28 |

29 – 33 |

34 – 38 |

39 – 46 |

Above 46 |

|

50 – 59 |

Below 19 |

19 – 23 |

24 – 27 |

28 – 34 |

35 – 42 |

Above 42 |

|

60 and over |

Below 15 |

15 – 18 |

19 – 21 |

22 – 29 |

30 – 38 |

Above 38 |

|

Number of Sit-Ups |

||||||

|

Women |

Very Poor |

Poor |

Fair |

Good |

Excellent |

Superior |

|

Age:Under 20 |

Below 28 |

28 – 31 |

32 – 35 |

36 – 45 |

46 – 54 |

Above 54 |

|

20 – 29 |

Below 24 |

24 – 31 |

32 – 37 |

38 – 43 |

44 – 50 |

Above 50 |

|

30 – 39 |

Below 20 |

20 – 24 |

25 – 28 |

29 – 34 |

35 – 41 |

Above 41 |

|

40 – 49 |

Below 14 |

14 – 19 |

20 – 23 |

24 – 28 |

29 – 37 |

Above 37 |

|

50 – 59 |

Below 10 |

10 – 13 |

14 – 19 |

20 – 23 |

24 – 29 |

Above 29 |

|

60 and over |

Below 3 |

3 – 5 |

6 – 10 |

11 – 16 |

17 – 27 |

Above 27 |

The Push-Up Test

- Equipment:

Mat or towel (optional)

In this test, you will perform either standard push-ups, or modified push-ups, in which you support yourself with your knees. The Cooper Institute developed the ratings for this test with men performing push-ups and women performing modified push-ups.

Biologically, males tend to be stronger than females; the modified technique reduces the need for upper-body strength in a test of muscular endurance. Therefore, for an accurate assessment of upper-body endurance, men should perform standard push-ups and women should perform modified push-ups. (However, in using push-ups as part of a strength-training program, individuals should choose the technique most appropriate for increasing their level of strength and endurance, regardless of gender.)

Instructions

- For push-ups: Start in the push-up position with your body supported by your hands and feet. For the modified push-ups: Start in the modified push-up position with your body supported by your hand and knees. For both positions, your arms and your back should be straight and your fingers pointed forward.

- Lower your chest to the floor with your back straight, and then return to the starting position.

- Perform as many push-ups as you can without stopping.

Number of push-ups: Number of modified push-ups: Rating Your Push-Up Test Result

Your score is the number of completed push-ups or modified push-ups. Refer to the appropriate portion of the table on page 19 for a rating of your upper-body endurance.

Record your rating below and in the chart at the end of this lab.

Rating:

Ratings for the Push-Up and Modified Push-Up Test:

|

Men |

Number of Modified Push-Ups |

|||||

|

Very Poor |

Poor |

Fair |

Good |

Excellent |

Superior |

|

|

Age: 18 – 29 |

Below 22 |

22 – 28 |

29 – 36 |

37 – 46 |

47 – 61 |

Above 61 |

|

30 – 39 |

Below 17 |

17 – 23 |

24 – 29 |

30 – 38 |

39 – 51 |

Above 51 |

|

40 – 49 |

Below 11 |

11 – 17 |

18 – 23 |

24 – 29 |

30 – 39 |

Above 39 |

|

50 – 59 |

Below 9 |

9 – 12 |

13 – 18 |

19 – 24 |

25 – 38 |

Above 38 |

|

60 and over |

Below 6 |

6 – 9 |

10 – 17 |

18 – 22 |

23 – 27 |

Above 27 |

|

Women |

Number of Modified Push-Ups |

|||||

|

Very Poor |

Poor |

Fair |

Good |

Excellent |

Superior |

|

|

Age:18 – 29 |

Below 17 |

17 – 22 |

23 – 29 |

30 – 35 |

36 – 44 |

Above 44 |

|

30 – 39 |

Below 11 |

11 – 18 |

19 – 23 |

24 – 30 |

31 – 38 |

Above 38 |

|

40 – 49 |

Below 6 |

6 – 12 |

13 – 17 |

18 – 23 |

24 – 32 |

Above 32 |

|

50 – 59 |

Below 6 |

6 – 11 |

12 – 16 |

17 – 20 |

21 – 27 |

Above 27 |

|

60 and over |

Below 2 |

2 – 4 |

5 – 11 |

12 – 14 |

15 – 19 |

Above 19 |

SOURCE: Based on norms from the Cooper Institute for Aerobic Research, Dallas, Texas; from the Physical Fitness Specialist Manual, Revised 2002. Used with permission.

The Squat Endurance Test

Instructions

- Stand with your feet placed slightly more than shoulder width apart, toes pointed out slightly, hands on hips or across your chest, head neutral, and back straight. Center your weight over your arches or slightly behind.

- Squat down, keeping your weight centered over your arches, until your thighs are parallel with the floor. Push back up to the starting position, maintaining a straight back and neutral head position.

Ratings for the Squat-Endurance Test:

- Perform as many squats as you can without stopping.

Number of squats:

Rating your Squat Endurance Test Result

Your score is the number of completed squats. Refer to the appropriate portion of the table for a rating of your leg muscular endurance. Record your rating below and in the summary at the end of this lab.

Rating:

Number of Squats Performed

|

Men |

Very Poor |

Poor |

Below Average |

Average |

Above Average |

Good |

Excellent |

|

Age: 18-25 |

<25 |

25-30 |

31-34 |

35-38 |

39-43 |

44-49 |

>49 |

|

26-35 |

<22 |

22-28 |

29-30 |

31-34 |

35-39 |

40-45 |

>45 |

|

36-45 |

<17 |

178-22 |

23-26 |

27-29 |

30-34 |

35-41 |

>41 |

|

46-55 |

<9 |

13-17 |

18-21 |

22-24 |

25-38 |

29-35 |

>35 |

|

56-65 |

<9 |

9-12 |

13-16 |

187-20 |

21-24 |

25-31 |

>31 |

|

65 + |

<7 |

7-10 |

11-14 |

15-18 |

19-21 |

22-28 |

>28 |

|

Women |

Very Poor |

Poor |

Below Average |

Average |

Above Average |

Good |

Excellent |

|

Age: 18-25 |

<18 |

18-24 |

25-28 |

29-32 |

33-36 |

37-43 |

>43 |

|

26-35 |

<20 |

13-20 |

21-24 |

25-28 |

29-32 |

33-39 |

>39 |

|

36-45 |

<7 |

7-14 |

15-18 |

19-22 |

23-26 |

27-33 |

>33 |

|

46-55 |

<5 |

5-9 |

10-13 |

14-17 |

18-21 |

22-27 |

>27 |

|

56-65 |

<3 |

3-6 |

7-9 |

10-12 |

13-17 |

18-24 |

>24 |

|

65 + |

<2 |

2-4 |

5-10 |

11-13 |

14-16 |

17-23 |

>23 |

SOURCE: Top End Sports. www.topendsports.com/testing/tests/home-squat.htm

Summary of Results

|

Test |

Number Performed |

Rating |

|

Sit-up Test |

|

|

|

Push-up Test |

|

|

|

Squat Endurance Test |

|

|

Using Your Results

- Are you at all surprised by your ratings for muscular endurance?

- What factors, if any, influenced your scores?

- Are you satisfied with your current level of muscular endurance as evidenced in your daily life, for example, your ability to carry groceries or your books, hike, and do yard work?