1 Introduction to the Building Industry

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Learn the Characteristics of the AEC Industry

- Understand the variety of projects performed within the industry

- Describe the scope and scale of the industry

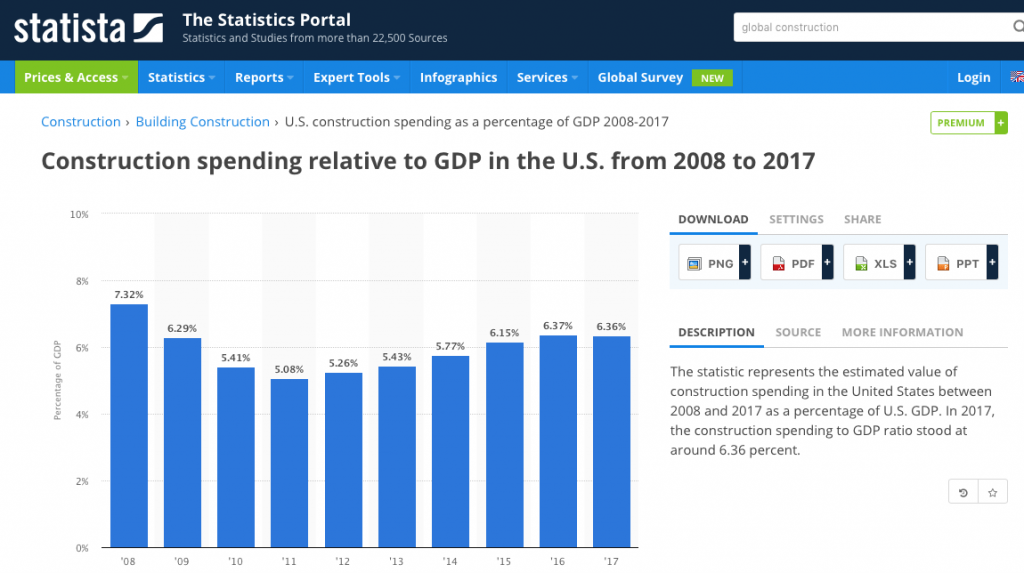

The Building Industry is large, in fact, very large. The overall industry is the 2nd largest industry in the United States economy, 2nd only to the healthcare industry. Within the United States market, the industry accounts for 6.1% (2016 data) of the annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the economy (Market Realist Website). The GDP is the value of all goods and services within an economy. Therefore, the Industry accounts for the same percentage of the economic transactions in the economy.

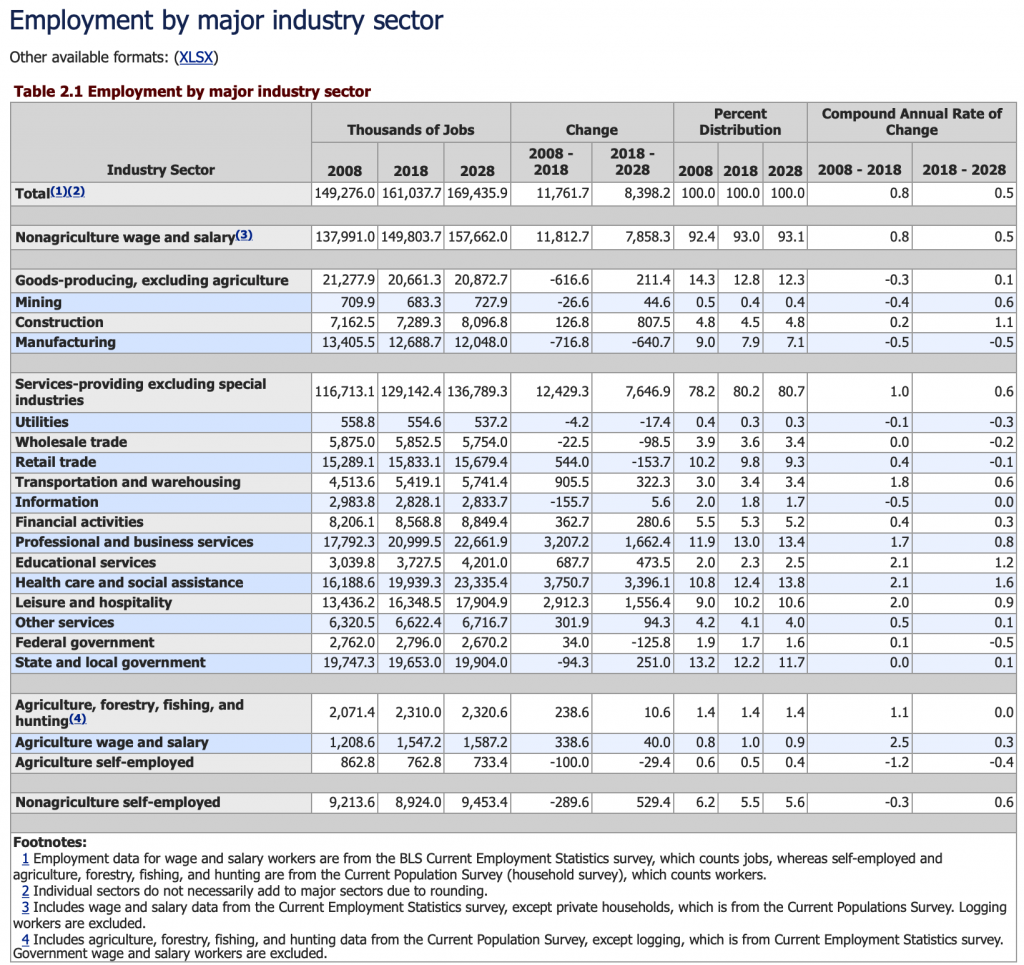

A reliable source of information on the construction sector is the U.S. Census Bureau. They maintain monthly data related to work put into place along with employment (see sample data from the website image in Figure 1). Visit the link to see the most recent data reported.

Figure 1-1: Construction Spending with Private and Public Breakdown

(Source: U.S. Census Bureau accessed Jan. 8, 2022)

Figure 1-1: Construction Spending with Private and Public Breakdown

(Source: U.S. Census Bureau accessed Jan. 8, 2022)

One challenge when discussing our industry is to define the scope and terminology used to describe the industry, or in some cases, subsets of the industry. At a broad level, some people refer to the industry as the Construction Industry, Building Industry, Architecture / Engineering / Construction (AEC) Industry, or even the Architecture / Engineering / Construction / Operation (AECO) Industry. People frequently use these terms interchangeably, and I will also do so throughout this book. The industry typically focuses on all the employees and tasks required to plan, design, construct, operate, and manage the delivery and operations of the built environment (commercial buildings, infrastructure, and industrial facilities). It is important to note that when people use the term ‘Construction Industry’, they are typically referring to the design, construction, and operations of facilities, not just the process of delivering a new facility. And when they use the term ‘Building Industry’, they are typically discussing all types of facilities, not just commercial and residential buildings.

The industry can be separated into different categories. One common breakdown is by the type of owner, and in particular, if the owner is a private entity (an individual or company) vs. a public (or government) entity. Another is to separate the industry by the type of facilities that are constructed. In this manner, we can separate the industry into four broad areas:

- Commercial Buildings;

- Infrastructure;

- Industrial; and

- Residential.

See the following information for some standard definitions of these sectors.

Commercial Buildings: Buildings and enclosures that contain a structure with enclosed space with an enclosure system with a non-industrial purpose. They may be fully enclosed, such are apartments or office buildings, or they may be partially open such as stadiums or monuments. Examples of buildings include office buildings, apartments, hospitals, rail stations, stadiums, arenas, and many more. Commercial buildings are typically designed by an architect. There may be many different types of owners.

Commercial Buildings: Buildings and enclosures that contain a structure with enclosed space with an enclosure system with a non-industrial purpose. They may be fully enclosed, such are apartments or office buildings, or they may be partially open such as stadiums or monuments. Examples of buildings include office buildings, apartments, hospitals, rail stations, stadiums, arenas, and many more. Commercial buildings are typically designed by an architect. There may be many different types of owners.

Infrastructure: Infrastructure facilities serve as core facilities that serve the public, which are not buildings. This category is sometimes referred to as ‘heavy’ construction. Examples include roads, bridges, dams, locks, and tunnels. These facilities are typically funded by the government. The design is typically led by an engineer such as a civil engineer. New infrastructure projects typically require a long planning and design phase.

Infrastructure: Infrastructure facilities serve as core facilities that serve the public, which are not buildings. This category is sometimes referred to as ‘heavy’ construction. Examples include roads, bridges, dams, locks, and tunnels. These facilities are typically funded by the government. The design is typically led by an engineer such as a civil engineer. New infrastructure projects typically require a long planning and design phase.

Industrial: Industrial facilities house core industrial processes, and the facility’s design is focused on the industrial process. Examples include refineries, power plants, chemical plants, and manufacturing facilities. The design of these facilities heavily depends on the process they support, so specialty engineers, in collaboration with civil engineers, frequently design them. Most of these projects are privately funded. Many of these projects are schedule-driven in order to start the process as soon as possible.

Industrial: Industrial facilities house core industrial processes, and the facility’s design is focused on the industrial process. Examples include refineries, power plants, chemical plants, and manufacturing facilities. The design of these facilities heavily depends on the process they support, so specialty engineers, in collaboration with civil engineers, frequently design them. Most of these projects are privately funded. Many of these projects are schedule-driven in order to start the process as soon as possible.

Residential: Residential buildings are built to house individuals or families. For the purpose of defining markets, the residential sector is focused on single-family detached housing or duplexes. These structures are typically wood, and they may be designed by an architect, or even a residential builder. While there are large-scale residential developers, many residential buildings are built by smaller companies. The barriers to entry into the residential market are less than other sectors since the buildings have a lower cost and lower level of sophistication. But, there are also many residential construction companies that fail each year.

Residential: Residential buildings are built to house individuals or families. For the purpose of defining markets, the residential sector is focused on single-family detached housing or duplexes. These structures are typically wood, and they may be designed by an architect, or even a residential builder. While there are large-scale residential developers, many residential buildings are built by smaller companies. The barriers to entry into the residential market are less than other sectors since the buildings have a lower cost and lower level of sophistication. But, there are also many residential construction companies that fail each year.

Note that this is not a perfect set of categories since it is sometimes difficult to define clear lines between the categories, as well as defining how to separate a large project into smaller components, but these categories do help us define the types of players in each market, and the typical characteristics of these different market sectors. Residential construction is a unique sector of our industry, and the market conditions for residential construction can vary significantly from the rest of the industry.

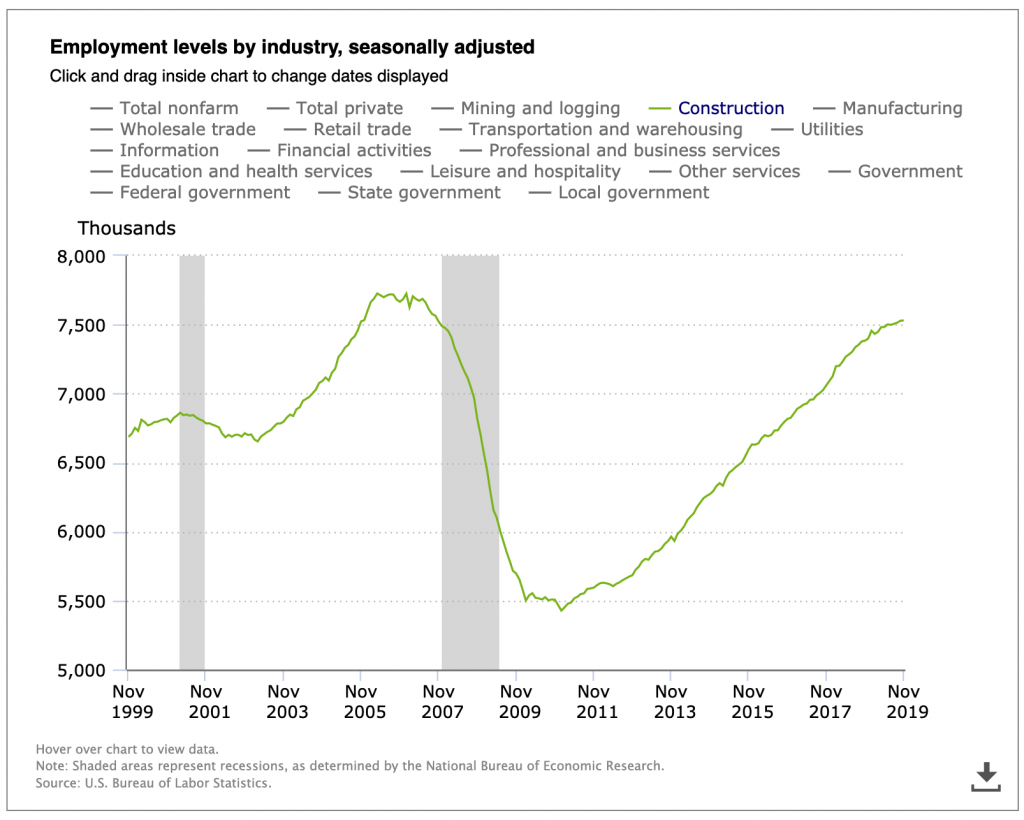

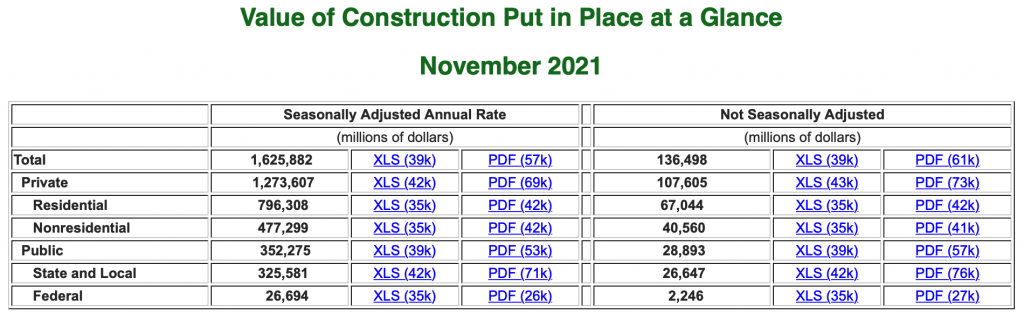

The construction industry is a major source of employment, especially if you also consider all the manufacturing industries that are supported by construction. In the United States, in 2016 it was estimated that the Industry was employing 7.3 million workers (2018 data) (see Fig. 1-2). This is 4.5% of the overall workforce. The Bureau of Labor Statistics is estimating that the workforce will grow at a rate of 1.1% per year between 2018 and 2028 (https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/employment-by-major-industry-sector.htm). In more recent statistics (see Figure 3), the industry employs over 7.5 million people. 14% of these jobs are current employees who are members of a union, which is down from 17.5% in 2000, although quite steady over the past 7 years. Note that these employment figures do not include all professional service employment related to the industry, nor do they include all the manufacturing jobs related to building supplies or transportation services for products to be shipped to the jobsite.

Figure 1-2: Employment Projections for Industry Sectors from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (Source: https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/employment-by-major-industry-sector.htm accessed Jan. 2, 2020)

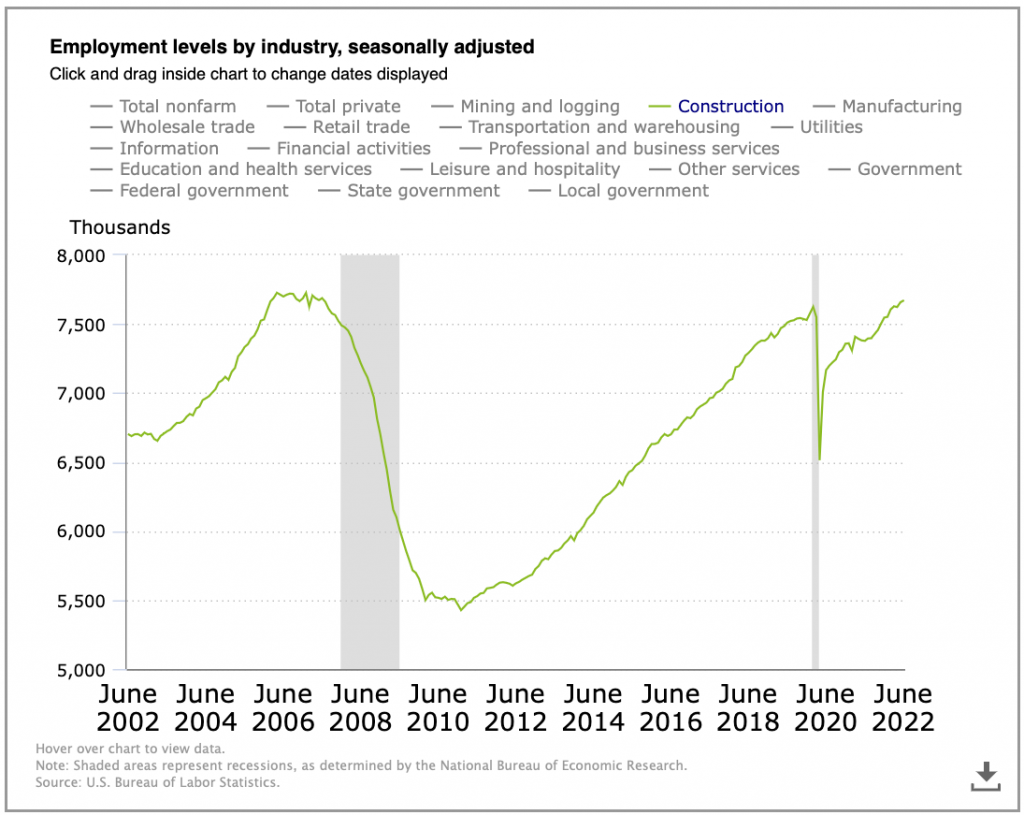

It is important to note that the number of employees within the construction industry can be significantly impacted by economic conditions. Figure 3 shows the construction sector employment against time. As you can see from the graph, the economic recession in 2007 and 2008 had a very significant impact on employment, going from approximately 7,600 employees in 2006 to 5,500 in 2009. This significant employment fluctuation can be a significant challenge. Once people leave the industry, it can be challenging to hire new workers. In fact, the most frequently cited challenge of general contractors right now is the lack of a skilled workforce. It is interesting to note that the recent COVID-19 pandemic has been the latest impact on employment in our industry. The initial onset of the pandemic in early 2020 caused a very abrupt, significant negative impact on employment, but that impact was very short-lived. Figure 1-4 shows the employment trend that includes more recent data, although the time periods are not displayed well in the image. It is interesting to note that the current employment (as of December 2021) is almost the same as the employment prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1-3: Employment Trend for Construction Employment from 1999-2019 (Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics accessed July 1, 2022)

Figure 1-4: Employment Trend for Construction Employment from 1985 to 2022 (Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics accessed July 1, 2022)

While the size and scale of the industry are impressive, this overall size and the nature of developing the built environment can also have significant negative impacts on environmental sustainability. Buildings account for 39% of all greenhouse gas emissions, and 70% of all electricity use (http://www.eesi.org/files/climate.pdf). The construction of the built environment can also add to the noise, light, water, air quality, and other pollutants. These negative impacts can be substantial, and there is a very important need for all members in the industry to focus on minimizing the negative environmental impacts of our industry. There are increasing efforts to address these impacts through increased awareness along with metric systems that provide recognition, and sometimes stipulations through zoning regulations and code requirements, for improved sustainability measures. Examples of these metric systems include the US Green Building Council’s LEED rating system (the most frequently used in the US), the Green Building Initiative’s Green Globes certification, the Living Building Challenge by the International Living Futures Institute, and Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM).

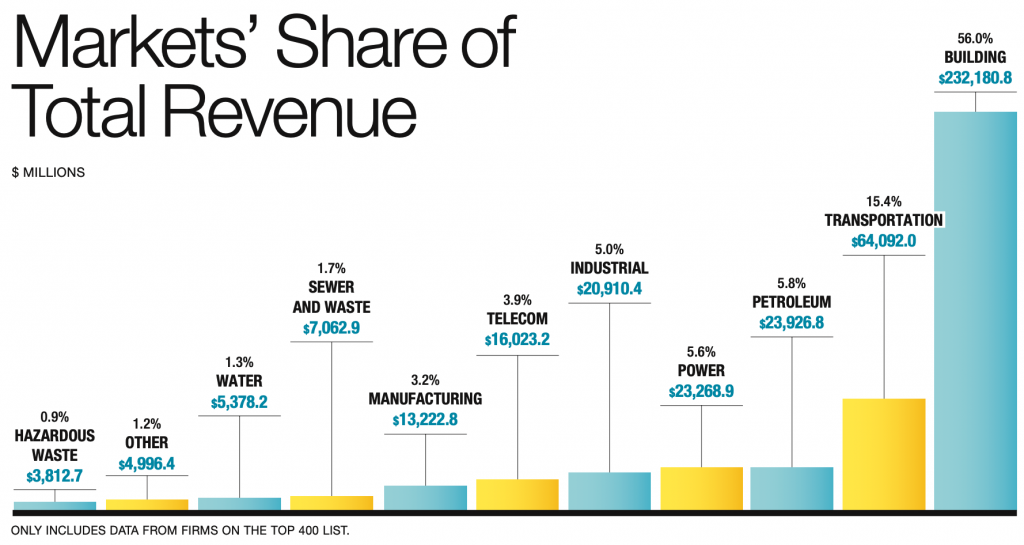

Each year, Engineering News Record (ENR) performs a survey of all larger contractors, as well as designers and owners. ENR then compiles lists of the largest companies by category. One of the reports that they perform is the Top 400 Contractors list. It is important to note that this list is compiled from company self-reported data, not audited financial statements, and the rankings within the list are specific to revenue, which is the value of the revenue that the company receives for annual work performed. For large construction management firms, much of the revenue that they receive is then paid to their subcontractors and suppliers. But this data does show some interesting information. Figure 1-4 shows the breakdown of the revenue by ENR’s project categories. This shows that in 2017, 53% of the revenue from the Top 400 contractors was from Buildings. It also shows that the second-largest category is Transportation, but it is a significantly smaller percentage, at 14%. It is important to note that the recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act federal funding bill will significantly increase this funding for transportation.

Figure 1-4: Top 400 Contractors – Revenue by Project (Source: ENR 2021)

Figure 1-5: Construction Spending Relative to GDP in the US (Source: Statista: The Statistics Portal (2018) Website: https://www.statista.com/statistics/226361/us-construction-spending-relative-to-gdp/ Accessed on July 26, 2018)

Professional Engineering Licensure

Professional Engineering Licensure plays an important role in ensuring that engineers who develop designs and manage the processes to bring them into reality are competent and qualified. Architectural Engineering and Civil Engineering students who complete their degrees should strongly consider a pathway toward becoming a licensed Professional Engineer (PE). For some disciplines, a PE is required to perform certain work tasks, e.g., structural plans must be verified by a PE for submission for a building permit. A PE can also be helpful to illustrate your capabilities when applying for job opportunities or to show your engineering background in a job that may or may not require an engineering degree.

The National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying (NCEES) was established to provide uniformity across states related to obtaining a PE license, although individual states within the U.S. administer the licensing process per their laws and rules, which may have additional requirements.

To obtain a PE License, a professional must:

- Pass the Fundamentals of Engineering (FE) exam (after completing two years of an ABET Accredited Engineering Degree program);

- Graduate from an ABET Accredited Engineering Program;

- Gain four years of progressive experience (note that a graduate degree can count for a year of experience);

- Complete an application to qualify to take the Principles and Practices Exam; and

- Pass the Principles and Practices Exam.

After you receive your PE in Pennsylvania, you must obtain at least 24 hours of continuing education per each 2-year period to maintain your licensure status. Also note that once a candidate has taken and passed the FE exam, they will be notified that they have passed. At this point, it is up to the individual to apply for certification as an Engineer In Training, EIT. When you have graduated, go to the following Professional Credential Services website and follow the instructions on the webpage. The progressive experience only starts following receipt of your EIT status.

For additional information, please see the following online resources:

Review Questions

Independent Activity:

Go online to see the latest reported construction market information from the US Census Bureau. Using seasonally adjusted annual rates, answer the following questions.

a, What is the current annual size of the Construction Market within the US?

b. How much has the market grown or declined in the last year?

c. What percentage of the market is public sector construction?