Aftereffects

The Unwanted: Refugees, Migration and Resettlement

Suzanne D. Rutland

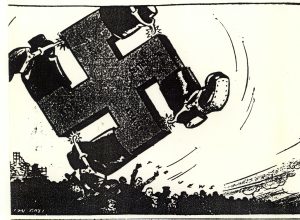

Immediately with the Nazi assumption of power in March 1933, Hitler began to implement racist policies that were outlined in Mein Kampf (The Struggle, 1923). In the antisemitic propaganda promoted by Hitler, Jewish people were like germs, bacilli and parasites, who were destroying Germany and had to be removed. Initial Nazi policies were designed to make life for the Jewish population of Germany so difficult that they would be forced to emigrate (Dwork & Pelt, 2009; Berenbaum, 1997).

Initial anti-Jewish Nazi policies and actions included:

- 1 April 1933 – a one-day, government endorsed boycott of Jewish businesses

- 7 April – introduction of the Civil Service Law, which meant that any Jewish person or political opponent employed by the government immediately lost their job. This included teachers, university lecturers, doctors and other medical people working in hospitals, as well as judges and lawyers working for the government.

- 8 April – Beginning of a campaign by the German Students Union leading to the raiding of libraries and bookshops and burning of any book written by a Jewish author or dealing with Jewish topics.

These actions were portents of what was to come. In response, out-migration of refugees from German began. Some saw the danger on the horizon and sought to escape as quickly as possible, especially those associated with Communism and Socialism. Non-Jewish people were also being persecuted and sent to the first concentration camp opened in 1933 at Dachau. Famous novelist Thomas Mann (a Hitler critic), his Jewish wife, and his adult children were among a small group of Germans who “voted with their feet” and migrated from Germany early in 1933, following Hitler’s rise to power (Dwork & Pelt, 2009).

After the boycott and first wave of discriminatory laws, some Jewish Germans fled without any plans. Others were able to return to home countries. Jewish photo-journalist and Hungarian Stefan Lorant, who would later publish his diary (Lorant, 1935), was arrested and sent to the newly opened concentration camp in Dachau, but later released and able to escape persecution (Gilbert, 2001).

Some refugees made more careful preparations to migrate. Otto Frank, father of the famous child-diarist, left for Holland in the summer of 1933 and registered his office with the Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce (his wife and children joined him a few months later). The Frank family were among about 45,000 Jewish and 10,000 gentile (mostly urban) Germans who fled in 1933 to find (at least temporarily) safe havens (Dwork & Pelt, 2009). Holland (Moore, 1986), France (Caron, 1999) and Belgium (Michman, 1998) were among the first nations to create national committees for refugees, developing programs (including agricultural training) for the growing flow of people coming from Germany. The Nobel laureate Albert Einstein was traveling and a visiting lecturer in the United States when the Nazis came to power; he resigned his German job in March 1933 and became an early faculty member at the newly created Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton New Jersey (Dwork & Pelt, 2009; Gilbert, 2007).

However, the majority of German Jews were not willing or able to emigrate from Germany or later from occupied zones. They believed that Nazism was a passing phenomenon and that they just had to sit it out. Those who had fought in World War I thought that their army service would protect them and their families; some Nazi restrictions initially excluded these veterans, as a concession to Paul von Hindenburg, a hero of World War 1 (Berenbaum, 1997).

Even so, Hitler’s government in Berlin did not initially respond to the out-flow of these early refugees. However, after anti-Nazi demonstrations in New York took place, Nazi leaders and people in other nations became more concerned about troubles from refugees who supported human rights. This was only one stage in the systemic scapegoating of competing and stigmatized groups, including political opponents, Jewish and Roma people, and people with disabilities.

The German Jewish poet, Heinrich Heine, who had converted to Christianity but could not escape his Jewish heritage, wrote in the early 1800s that those who burn books will, in the end, burn people. Tragically, these words were to prove prophetic, not just for the Jewish population of Germany but for all European Jews who came under German domination. The Jews of Germany were then a small minority of the population, constituting only 0.8% of the population, but they faced an ongoing process of exclusion from German society.

In September 1935 the “Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honour” was introduced and was further refined in November 1935 with the “First Supplementary Decree of the Rich Citizenship Law” which defined who was a Jewish person as “anyone who is descended from at least three grandparents who are racially full Jews” (Dwork & Pelt, 2009: 88-89). These laws, known collectively as the Nuremberg Laws, led to a further deterioration of conditions. Jewish people became second class citizens in Germany, with no protection from false accusations and the wide-spread loss of their livelihoods. For example, Jewish men could be accused of having sexual relations with a non-Jewish woman, which was forbidden under the new laws. This could lead to their imprisonment and loss of everything they owned.

The English-speaking countries, and indeed the world, reacted with mixed responses (Marrus, 1985; Wyman 1968). In England, Churchill denounced the measures as ‘persecution’ in an article in Strand magazine (Gilbert, 2001) but introducing practical proposals for a solution did not eventuate. Nations were enduring the Great Depression following the Wall Street crash of 1929. A high proportion of their citizens were unemployed so that the key players argued that they were in no position to assist the Jewish refugees. Many considered Nazism to be preferable to Communism; as the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald wrote on March 2, 1933, “German civilisation and all that it means to the world should be able without difficulty to survive a Hitler dictatorship. But no West European could regard without despair a repetition of the destruction which Sovietism wrought in Russia” (Rutland, 1978, p. 144).

Antisemitic attitudes in the free world contributed to opposition to Jewish refugee migration (Wasserstein, 1999; Kushner, 1989). The typical stereotypes of Jewish persons tended to be highlighted, together with fears that the refugees would undermine living standards and create economic competition, displacing local workers. In May 1939 in Australia, Sir Frank Clarke, president of the Victorian Legislative Council, bitterly attacked the refugees, claiming “Hundreds of weedy East Europeans, slinking rat-faced men under five feet in height… worked in backyard factories in Carlton and North Melbourne for two or three shillings a week and their keep… No Australian factory could compete with such prices and pay awards” (Rutland, 2001, p. 190).

Winston Churchill warned that “there is a danger of the odious conditions now ruling in Germany being extended by conquest to Poland and another persecution and pogrom of Jews being begun in this new era” (Gilbert, 2007, p.100). After a meeting with Albert Einstein, who described the dire situation for Jews in Germany, Churchill tried to advocate for German Jewish medical and science students at the University of Bristol, where he had been Chancellor. The response of the university administration was that there was no place for students from foreign countries (Gilbert, 2007). Similarly, in Australia, the medical associations sought to keep Jewish doctors out (Rutland, 1983).

British policy towards the plight of Jewish people responded to the worsening situation, as well as to events in Palestine (London, 2001, Sherman, 1973, 1994). The Labour government, headed by Ramsay MacDonald, but with Conservative support, strongly supported the post-World-War I German disarmament. While he did not support the Nazi regime, MacDonald felt that this was an internal German matter and that “the fierce passions that are raging in Germany have not found, as yet any other outlet but upon Germans” (Gilbert, 2007, p. 100). Thus, initially Britain was slow to accept Jewish refugees, although this was to change dramatically with the events of 1938 (Wasserstein, 1979).

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the U.S. president who had been elected in November 1932, was faced with the task of repairing the American economy. He introduced a “New Deal,” with major economic reforms for industry and agriculture beginning in 1933. Faced with public fears of immigrants and national isolationism, the U.S. leadership was not prepared to liberalise immigration policies for Jewish refugees from Nazism (Erbelding, 2018; Wyman, 1985; Feingold, 1970). In Canada, there were similar issues (Abella and Troper, 1983).

Australia was particularly badly hit by the Depression. With a third of its workforce out of work, and with many having lost their homes and being forced to live in tent cities, there was to be no liberalisation of immigration laws before 1936. Only dependent children and single women were allowed to enter, and there was a requirement for £200 landing money, a sum more than the annual average Australian salary. In the period from 1933-1937, only a few hundred Jewish refugees managed to find sanctuary in Australia (Rutland, 2001; Bartrop, 1994; Blakeney, 1985)

With the Olympic Games being held in Berlin, Hitler temporarily halted his anti-Jewish campaign and tried to camouflage his anti-Jewish policies. Signs such as “Jews not wanted here”, or “No Jews allowed” on park benches, and other antisemitic slogans were removed. His anti-Jewish policies continued into 1937, but most German Jews stayed put.

The European situation changed dramatically in March, 1938 with the Nazi takeover of Austria, known as the Anschluss. While Nazi anti-Jewish policies had evolved in a piecemeal fashion in the five years since Hitler’s take over in 1933, the situation was very different in Austria. From the very beginning of German occupation, Jewish people felt the full brunt of Nazi anti-Jewish policies. Viennese Jews were persecuted, made to scrub the streets with toothbrushes to remove graffiti. They faced violence and looting from Nazi supporters when “the mob fury was let loose on the defenceless Jews” (Grenville, 2010).

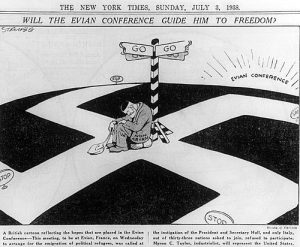

In response to the increasing numbers of German and Austrian Jews seeking to emigrate, President Roosevelt convened an international Evian Conference at Lake Evian in France. However, since the United States did not wish to change its own quotas and immigration policies, Roosevelt wrote that no country would be required to change its policies specifically to assist Jewish people. Thirty-two nations assembled at Evian in June 1939 to discuss the mounting refugee crisis (Bartrop, 2018). The Australian delegate, Thomas W. White, the Minister for Trade and Commerce visiting Europe at the time, stated that “Australia does not have a racial problem and is not desirous of importing one by encouraging any scheme of large-scale foreign migration.” As Australian historian Paul Bartrop, stated, “Australia typified the world’s approach as it stood in mid-1938. Only the tiny Dominican Republic in the Caribbean was prepared to take in refugees” (Bartrop, 1994, p.78).

In his summing up the significance of Evian, Australian External Affairs adviser at the conference, Alfred Stirling, stated that the Conference “made little or no progress” on the refugee issue. It merely acted “as a salve for the international conscience” (Rutland, 2001, p.180). Its only success was the creation of the International Government Committee with a permanent office in London, headed by an American (Bartrop, 2018). Given American’s isolationist policy, for the Europeans this was an achievement, although the Committee was soon dormant because it lacked substantial funds. German and Austrian Jews had to rely on the Jewish organisations, such as the Jewish Refugee Fund established at Woburn House, London, in 1933, and the American Jewish welfare organisations for assistance.

For Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime, the Evian Conference was a green light. The reactions of the various countries attending made it clear that the world was not prepared to act to save Jewish people. This was a turning point, which led to the second immigration phase.

Migrations out from Germany and occupied nations

From mid-1938 the situation for the Jews of Europe rapidly deteriorated. Hitler started to make demands on Czechoslovakia relating to the Sudetenland, a mountainous area on the border of Czechoslovakia, which had a large German speaking population and formed a natural defense barrier for the central European country. In September 1938, French, British and Italian leaders met with Hitler to discuss the mounting crisis in the region and signed what became known as the Munich Agreement, granting Germany control of the region. This meant even more Jews coming under Nazi rule. In March 1939 Hitler was able to march in a take over all of Czechoslovakia (Rosenbaum, 2017).

Then on 26 and 28 October 1938 the “Polish Action” took place in Germany. At all hours, the state police officers raided the homes of Polish Jews who had migrated to Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, arrested them, and forcibly loaded them onto specially guarded trains to the Polish border, where they were deposited in a no-man’s land. Poland refused to let them in, and these families were stranded, with no food and nowhere to stay (Dwork & Pelt, 2009). A total of ~17,000 were forced into exile in this way and faced catastrophic conditions on the German/Polish border.

Herschel Grynspan was a son of one such expelled and dislocated couple. Grynspan was living in Paris and responded by marching into the German Embassy where he attempted to assassinate the third consul, Ernst Von Rath. While there were complexities with this story, Hitler used it as a pretext to launch what he called “a spontaneous response of the German people.” In fact, this was an orchestrated police action, a German pogrom on 9-10 November (Dwork & Pelt, 2009). Known as Kristallnacht because of shop windows which were smashed during the violent rampage which occurred across Germany. Jewish property was destroyed, synagogues were burnt to the ground and Jewish vulnerability fully revealed. 30,000 men and boys were arrested and incarcerated in concentration camps in inhumane conditions (Friedlander, 1997, 2007). This was a watershed event that marked a major turning point in the destruction of European Jewry.

Kristallnacht convinced most German and Austria Jews that they had to leave immediately. At the same time, incarcerated men could only be released if the family could provide (difficult-to-obtain) emigration papers (Dwork & Pelt, 2009). One choiceless choice that was discussed by families was where to go; the doors of most countries remained firmly shut. Neither the United States (Breitman & Kraut, 1987) nor Canada (Abella & Troper, 1986) were prepared to increase their immigration quotas.

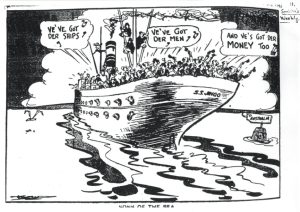

The South African government’s response was initially quite liberal in the period from 1930-1936, but in 1936 the SS Stuttgart arrived with 500 German Jewish refugees on board, resulting in a public outcry. In response, the government cut off further Jewish refugee migration to South Africa. Only a total of 6,000 were permitted to enter with half arriving before 1936 (Shain, 2015).

The Australian agent-general representing the Australian government in London and former prime minister, Stanley Bruce, sent an urgent telegram to the Australian government, urging them to increase the planned quota from 15,000 over three years to 30,000. The Australian government rejected this request, and on 1 December 1939, John McEwen, the Minister in charge, formerly announced the quota of 15,000 in parliament (Rutland, 2001; Bartrop, 1994).

Shanghai was one of the few places in the world which offered a refuge. It had been captured by the Japanese in 1937 and did not require a formal visa. Around 20,000 German, Austrian and Czechoslovak Jews managed to travel there before the war broke out in September 1939 (Ristaino, 2001; Kranzler, 1976).

British policy was complex. On the one hand, the British government restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine and tried to cut off the illegal immigration of German and later Austrian Jews who tried to enter the Jewish homeland. In response to the Arab revolt of 1936-1939, the MacDonald White Paper was introduced, limiting Jewish migration to 75,000 over five years, after which all Jewish migration to Palestine was to cease (Kushner, 2002; London, 2001; Sherman, 1984; Wasserstein, 1979).

On the other hand, in response to an outcry in Britain from private citizens and the church and from a sense of British guilt over its appeasement of Hitler with the Munich agreement with the subsequent violence of Kristallnacht, various programs were introduced enabling large numbers of refugees to arrive in the year before the outbreak of war (Kushner, 2002). These permitted certain categories of refugees to enter Britain: those who had capital to establish new industries; domestic servants; and children under the age of 17. As a result, over 60,000 Jews were rescued by migrating to Britain. This was a significant number and proportionately the most generous response, although the British hoped many of these would migrate onto the “colonies,” that is Canada, Australia, and South Africa (London, 2001; Sherman, 1984; Wasserstein, 1979).

One of the most moving of these programs was the Kindertransport an organized program to bring children from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, which in the end rescued over 10,000 children. The sense of stress and impending doom of parents in Austria and Germany was seen in their willingness to part from their children, some as young as three, sending them to Britain, not knowing if they would ever see them again. It was a heartrending decision (Dwork & Pelt, 2009).

One of the great heroes of rescue was Nicholas Winton. A British businessman, Winton was in Prague in December 1938, after the Nazi takeover of the Sudetenland created a severe refugee problem and was shocked at the situation. While other refugee organizations were focusing on assisting adults to leave Europe, he decided to try and rescue as many children as he could. He returned to London, and single handed created a rescue operation which in the end saved the lives of 669 Czech children (Emanuel & Gissing, 2020).

The governments of the Anglo-world would permit only certain categories of refugees to enter. They used the fear of an increase in antisemitism as a reason for their restrictive policies; expected the newcomers to acculturate immediately, not to speak German in public and to minimize their “foreignness.”

In the 1930s, with countries still deeply affected by the depression, antisemitic and other concerns that Jewish refugees should not become a public charge on the state led to administrative requirements being introduced by bureaucrats to limit the number of immigration visas and to ensure that the refugee migration programs were financed by the local Jewish communities, so that the Jewish refugees would not become a charge on the state (London, 2001; Rutland, 2001, Kushner, 1994). As Breitman and Kraut (1987) note, “few bureaucrats were willing to consider the rescue of persecuted foreigners as compatible with the defense of the national interest… so that bureaucratic indifference to moral or humanitarian concerns was a more important obstacle [than antisemitism] to an active refugee policy” (p. 9).

With the outbreak of war in September 1939, the escape routes seemed to all be closed due to the danger of shipping being attacked by German submarines. Following the British withdrawal from the European continent with Dunkirk, Jewish men and boys in Britain from the age of 16 were classified as “enemy aliens” and many were placed in internment camps (Cesarani and Kushner, 1993). A number were sent to Canada and a group of over 2000 also sent to Australia (Bartop, 1994). This mindless action, which meant that Jews were placed together with actual Nazis led to further suffering for these internees who had already gone through significant trauma with their escape from the Nazi clutches.

The phase of forced emigration by the Nazis came to an end with the Nazi Operation Barbarossa, the German government breaking their treaty agreement with the Soviet Union and invading Eastern Europe in July 1941. Groups of ‘action squads’ organized many mass shootings, which led to a million Jews being murdered by the end of 1941. This ‘Holocaust by bullets” was followed by the construction of death camps, of which Auschwitz-Birkenau was the largest. By the end of 1942, the mass murder of over three million Jews had been revealed. Britain and the United States announced strong statements in mid-December 1942 and many called for rescue efforts.

The public outcry in both countries led to the need to act. Again, a conference was held, this time in Bermuda with just British and American representatives. The delegates spent ten days discussing and debating ways to assist Jewish refugees, but neither country was prepared to increase their quotas, or to even countenance establishing camps for large numbers in the North African countries which they had already conquered. This was particularly important for those refugees who had managed to escape from Vichy France by crossing the Pyrenees into Spain and then into Portugal. Both countries raised various obstacles and limitations to every proposal (Breitman & Kraut, 1987; Wasserstein, 1979).

After the meeting, the British delegates admitted that the results had been “insubstantial” and noted that there would be no change if “the present combination, in so many countries, of pity for Jews under German control and extreme reluctance to admit further Jews into their borders persists” (Wasserstein 1979, 201). Thus, the result of the Bermuda Conference paralleled that of the Evian Conference and there was no progress.

Only in 1944 did Roosevelt finally act with the establishment of the War Refugee Board, which provided significant funding to save civilians who were being murdered in war zones (Erbelding, 2018; Wyman, 2007; Breitman & Kraut, 1987). This assisted but did not prevent the Nazis from mass murder of Hungarian Jewry, by then the largest Jewish community remaining intact. Funding from the United States assisted Raoul Wallenberg and others to establish safe houses in Budapest, helping to save thousands of lives. However, this aid was too little too late.

In the meantime, throughout the war years, Britain continued to prevent Jewish refugees from arriving in Palestine by maintaining a severe military blockade, leading to tragic consequences. For example, the VD Struma, an “illegal”, unseaworthy immigrant ship which had sought to land its passengers in Palestine, was turned back at Constantinople after the British mandatory authorities refused its entry into Palestine. On March 25, 1942, the ship sunk in the Black Sea with the loss of 762 lives (Rutland, 2001). By removing Palestine as an escape route, as well as refusing to admit significant numbers of refugees elsewhere, British decisions sent many Jews to their death (London 2000; Wasserstein 1979).

The record of the other English-speaking countries, including the United States, Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand was even less impressive than the British (Beaglehole, 2015; Shain 2015; Wyman, 2007; Bartrop, 1994; Breitman & Klaut, 1987; Abella and Troper, 1986; Blakeney, 1985). In all, in the period between 1933 and 1944, Breitman and Kraut estimate that a maximum figure of 250,000 Jewish immigrants entered the United States, with the annual quota never exceeding 54% of the overall quota (153,774). Britain accepted about 70,000, Australia about 9,000, and Canada only 5,000 (Arbella and Troper, 1986).

There has been significant academic debate about these restrictive policies. Initially, the Allies believed that in defeating Nazism, their conduct was justified and there was “self-congratulation, rather than self-approach” (Cesarani and Levine, 2002, p.5). From the late 1970s and 1980s, as government archives began to open up, the debate focused on the anti-Jewish attitudes of public servants and politicians (Sherman, 1987; Breitman and Kraut, 1987; Abella and Troper, 1986; Wyman, 1985; Feingold 1970).

Scholarship gradually became more nuanced, examining a series of factors (Wasserstein, 1999). A polarization emerged, with Penkower (1988) being highly critical of the Anglo-nations failure of rescue, while, in his book, The Myth of Rescue, Rubinstein (1997) argued that the Allies did everything they could in their power, and that no Jewish lives were lost due to Allied policies – Hitler and Nazi held primary responsibility for the Holocaust. Since then, more nuanced studies have emerged such as London (2002) which seek to understand the complexity of human motivations. As Marrus argues, a historian’s task is to explain and not to condemn (Kushner, 2002).

Post-war: Migrations from DP camps

At the end of the war, as allied troops liberated camps and the Nazis surrendered, there were over eight million Displaced Persons (DPs), or foreign nationals who needed Allied assistance and care before being repatriated to their nations-of-origin. DPs included forced and voluntary laborers, POWs, and remaining concentration camp inmates. Many needed immediate assistance and care, and some were still living in former concentration camps. Among the DPs were ninety thousand Jewish DPs, many of whom became known as the ‘surviving remnant’ of European Jewry (Patt, 2020, 163).

Some liberated Jews made the choice to return to their nations-of-origin, searching for families and pre-war homes and communities. Others refused and sought new lives in new nations, hoping for greater safety and opportunities. Those unable to return to pre-war homes became stateless, but there were many needs among many national groups. Relief efforts grew, led by the Allies, and included the UNRRA, the JDC, and others.

In order to deal with this crisis and situation the UN established the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) in December 1946. By the early 1950s most of non-returning DPs been assisted to migrate elsewhere, including to the United States, UK, Canada and Australia. Australia received 170,000 almost all non-Jews as Jewish persons were excluded from the Australian program, and the other English-speaking countries also introduced similar policies, so that the post-war Jewish story was different.

After Germany’s surrender in May 1945, there were strong reactions to DPs from members of both the American and British armies. US General Dwight Eisenhower visited concentration camps beginning in April 1944, writing to US Army Chief George Marshall that cruelty in the (too often minimized) atrocity reports were an “understatement” of the situation. Marrus (1985), wrote that Jewish survivors liberated from concentration camps were so emaciated and degraded that “an abyss separated inmates of camps like Dachau from the rest of humanity… However horrified, the liberators failed to see the victims as fellow creatures” (pp. 307-308). At the same time, national policies were less than conducive to migration; immigration was still limited and guarded. The British government avoided introducing any notion of Jewish particularity into their official policies, because of their desire to prevent Jewish refugees from having any claim to Palestine.

Jewish survivors initially were grouped together with non-Jews, and all were grouped by place of origin (Patt 2020). Every effort was made to repatriate them to eastern Europe, a policy strongly advocated by Ernest Bevin, the British Foreign Secretary (Kushner, 1994). Many of these Jewish DPs did return to the East, to their hometowns in Poland and elsewhere, as did those Jews who had survived in the Soviet Union. On their return they often found that their non-Jewish neighbours had taken over their homes and, in most cases, refused to hand them back. They faced further antisemitism and in July 1946 a pogrom took place in the Polish city of Kielce, when 41 Jews were murdered and many others wounded (Bauer, 1970).

This was a catalyst for the flight of Jews from Poland, back to the DP camps in 1946 and 1947 (Berenbaum & Peck, 1998). They wished to leave Europe but faced the prospect that they were still not welcomed anywhere. The British government was still severely restricting Jewish migration to Palestine, although efforts were made to smuggle in Jewish survivors of the Holocaust (Cohen, 1991; Szulc, 1991, Sachar, 1983; Bauer, 1970).

After 1945, throughout the English-speaking world and including the United States, Britain, Canada, and Australia, there was a fear of an influx of Jewish survivors. This fear was fuelled by xenophobia and antisemitism in these countries (Rutland, 2001), as well as by what Kushner (2002, 1994) has described as “liberal ambivalence”, that is the fear that “[Jews] bring antisemitism with them” (67). As noted by Irving Abella and Harold Troper (1986) in their study of Canadian responses to the refugee crisis, the Western world was “prepared to eulogize the Jews; it was not prepared to offer them a new home” (p. 284).

In the US, only one refugee resettlement camp was created, located in Oswego NY. Even there, Jews remained behind fences and treated with uncertainty for a long time. In many places, Jews were too often unwelcome and subject to pervasive antisemitism, cast as “clannish, aggressive and cosmopolitan,” a group that did not assimilate easily and whose loyalty would always be suspect (Abella and Troper, 1983, p. 281).

Consequently, many felt that Jewish refugees should be kept out, even while native-born Jewish people often enjoyed significant levels of acceptance and integration into English-speaking nations. Politicians did not immediately or often support a broadening of Jewish refugee immigration, often out of fear of a political backlash, and they were largely supported in these policies by cooperative government officials (Kushner, 2002; London, 2001; Kochavi, 2001; Rutland, 2001; Kushner, 1994; Blakeney, 1985; Dinnerstein, 1982).

When Jewish survivors began to stream back to the West from Poland, the British restricted Jewish entry into their post-war occupation zone so that most sought to enter the American zone (Berenbaum & Peck, 1998). Despite the stream of DPs entering the American zone, fear of an influx of displaced persons in the United States combined with antisemitism to limit the number of Jewish DPs permitted to enter the country.

In December 1945, U.S. President Harry S. Truman had responded in a humanitarian manner by issuing a special directive permitting the resumption of quota immigration to the United States from the areas of greatest need. In addition, a “corporate affidavit” was introduced, guaranteeing the pledge given by voluntary agencies—including major Jewish welfare organizations—that sponsored immigrants would not become a charge on the state (Cohen, 2007). After years of protesting and being ignored (Sarna 2004), Jewish leaders and relief organizations finally had help from federal authorities to bring refugees to the U.S. (Dinnerstein, 1982).

Between May 1946, when the first refugee ship arrived, until June 1948 when a new act came into operation, Jewish survivors constituted two-thirds of the 41,379 people admitted under the program. However, the program was met with a nativist and antisemitic reaction. For example, shortly after Truman’s policy on refugees was announced, an attorney for the Citizen’s Committee on Displaced Persons noted that “the general sentiment in Congress at the present . . . [is] still too hostile, particularly because of the feeling that too many Jews would come into the country if immigration regulations were relaxed” (Dinnerstein, 1982, pp. 137-8). In November 1946, Republican William Chapman Revercomb visited Europe to investigate DP conditions. Although he praised the non-Jewish DPs from the Baltic states, his report was very critical of the Jewish DPs, whom he associated with Communists. Revercomb, who in 1948 assumed the chairmanship of the U.S. Senate’s immigration subcommittee, predicted that it was “very doubtful that any country would desire these [Jewish] people as immigrants” (Dinnerstein, 1982, pp. 139-140).

These sentiments were reflected in the Displaced Persons Act of June 1948. The U.S. Congress permitted a quota of 205,000 DPs to immigrate to the United States over the subsequent two years, but the act included provisions that worked against the entry of Jewish refugees. It defined a displaced person as one who had been in a DP camp since December 22, 1945. According to Dinnerstein (1982), this decision “reflected the lawmakers’ desire to exclude Jews” (p. 166). Truman reluctantly agreed to sign the bill, while expressing dissatisfaction with its ‘callous’ discrimination against Jewish DPs.

In fact, more than 85 percent of Jewish DPs were rendered ineligible for admission to the United States under the 1948 act because of their late date of arrival in the American, British, or French occupation zones. The act also stipulated that 30 percent of entrance visas be given to agricultural workers, who had to agree to continue as farmers in the United States (Cohen, 2007). This further disadvantaged the Jewish DPs, as few of them were farmers. In addition, 40 percent of the DPs had to come from areas annexed by the Soviet Union after the war, meaning mainly the Baltic countries and the Ukraine, areas where the vast majority of Jews had been murdered. As a result, most DPs who qualified under this provision were non-Jews, including some Nazi collaborators.

At the same time, the Volksdeutsche ethnic Germans” who had lived in the East and had fled to Germany, enjoyed advantages under the act, since they were accepted as part of the German quota and they could apply for a visa if they had reached West Germany by July 1, 1948. The Volksdeutsche also did not need an employment and housing guarantee, which was required for other DPs. With the introduction of the new act, 23,000 European DPs—mostly Jews—who had already been given preliminary approval to resettle in the United States were disqualified. Only the remaining thirty thousand Jewish refugees in the U.S. Zone who met the new cut–off date were allowed to proceed as planned (Dinnerstein, 1982).

The American Jewish leadership was horrified by the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, which it saw as antisemitic. While expressing their opposition to the new act, the key Jewish welfare organizations took an interest in any destination that would allow Jewish DPs to leave behind the horrors of Europe as quickly as possible, but possibilities were limited. The Canadian response was defined by the comment of one Canadian official – off the record – “None it too many!” (Abella and Troper, 1983).

The United Kingdom maintained its restrictive pre-war immigration policy, and did not continue with the more generous policies of special categories that it had introduced after Kristallnacht (London, 2001), and Australia introduced administrative quotas, ensuring that the number of Jewish DPS entering Australia was restricted. In 1950, when Australia accepted 100,000 non-Jewish DPs under the IRO program, the private Jewish quota was only 3,000, and even this was not filled (Rutland 2001).

Both the JDC (America Jewish Distribution Committee) and HIAS (Hebrew Immigration Aid Society) played a key role in assisting Jewish Holocaust survivors after the war (Patt, 2019; Bauer, 1989; Wischnitzer, 1956). In the end, half a million Jewish survivors were ferried to Israel after its creation in May 1948, assisted by the JDC, which received funding from the IRO (Patt, 2019; Bauer, 1989). Many of these survivors were not in the DP camps in 1945.

By 1952 almost all the camps had been closed apart from the Foehrenwald Camp – the last DP camp to be closed in Europe. The JDC and HIAS wanted Australia to take some of the DPs from there but this proved difficult. Many of the most problematic DPs for resettlement, including some who could not cope in Israel and who had returned to Germany, were being looked after there. Eventually solutions were found and this camp was also closed in 1957.

For survivors arriving in their new homelands, speaking about their Holocaust experiences was painful. The issue of what has become known as “The Silence,” that is the failure to address the Holocaust in the post-war era, has been the subject of much scholarly debate with some scholars (Diner, 2009; Cesarani & Sundquist, 2012) arguing that the survivor experience was talked about from the beginning while other scholars have argued that the silence was either due to political factors (Finkelstein, 2000; Novick, 1999), or that the impact of trauma was the main reason (Wajnryb, 2001).

Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate, Elie Wiesel, wrote and taught about his Holocaust experiences. His early text, entitled “And the world remained silent”, was published in Yiddish in 1956 and in French in 1958, but he had trouble finding a publisher for an English edition, with his manuscript being rejected by major American publishers. His first-hand description, entitled Night, was finally published there in 1960 (Borchardt, 2016). Wiesel became a symbol of the Holocaust and taught many of its importance, chairing the U.S. Holocaust commission that, starting in 1978, created the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

References

Abella, I. & Troper, H. (1983). None is too many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948. Random House.

Bartrop, P.R. (2018). The Evian Conference of 1938 and the Jewish refugee crisis. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bartrop, P.R. (1994). Australia and the Holocaust, 1933-1945. Australian Scholarly Publishing.

Bauer, Y. (1989). Out of the ashes: The impact of American Jews on Post-holocaust European Jewry. Pergamon Press.

Bauer, Y. (1970). Flight and rescue: Brichah. Random House.

Beaglehole, A. (2015 [1988]). A small price to pay: Refugees from Hitler in New Zealand 1936–46. Bridget Williams Books.

Berenbaum, M. (Ed.). (1997). Witness to the Holocaust (1. ed). Harper Collins Publ.

Berenbaum, M., and Peck, A.J. (Eds) (1998). The Survivor Experience. In The Holocaust and History: The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed, and the Reexamined, pp. 691-812. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Blakeney, M. (1985). Australia and the Jewish refugees, 1933-1948. Croom Helm.

Borchardt, G. (2016). How NIght was published in America. French Culture Website. https://frenchculture.org/books-and-ideas/3790-how-night-was-published-america. Accessed January 18, 2021.

Breitman, R and Kraut, A.M. (1987). American refugee policy and European Jewry, 1933-1945. Indiana University Press.

Burstin, B.S. (1989). After the Holocaust: The Migration of Polish Jews and Christians to Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh.

Caron, V. (1999). Uneasy asylum: France and the Jewish refugee crisis, 1933-1942. Stanford University Press.

Cesarani, D. and Sundquist, E.J. (Eds.). (2012). After the Holocaust: Challenging the myth of silence. Routledge.

Cesarani, D. and Kushner, T. (1993). The internment of aliens in twentieth century Britain, Frank Cass.

Cesarani, D. and Levine, P.A. (2002) “Introduction”, “Bystanders” to the Holocaust: A re-evaluation. Frank Cass.

Cohen, B.B. (2007). Case closed: Holocaust survivors in post-war America. Rutgers University Press.

Cohen, E.J. (1991). Rescue. Riverside Publishing Company.

Diner, H. R. (2009). We Remember with Reverence and Love: American Jews and the Myth of Silence after the Holocaust, 1945-1962. New York University Press.

Dinnerstein, L. (1982). America and the survivors of the Holocaust. Columbia University Press.

Dwork, D., & Pelt, R. J. van. (2009). Flight from the Reich: Refugee Jews, 1933-1946 (1st ed). W.W. Norton.

Emanuel, M. and Gissing, V. (2002) Nicholas Winton and the rescued generation. Vallentine Mitchell.

Erbelding, R. (2018). Rescue Board: The untold story of America’s efforts to save the Jews of Europe (First edition). Doubleday.

Feingold, H.L. (1970). The Politics of Rescue: The Roosevelt administration and the Holocaust, 1938-1945. Rutgers University Press.

Finkelstein, N. (2000). The Holocaust Industry: reflection on the exploitation of Jewish suffering. VERSO.

Friedlander, S. (2007). Nazi Germany and the Jews: The years of extermination, 1939-1945.

Friedlander, S. (1997). Nazi Germany and the Jews: The years of persecution, 1933-1939.

Gilbert, M. (2007). Churchill and the Jews. Henry Holt.

Gilbert, M. (2001). The Jews in the twentieth century (1st ed). Schocken Books.

Grenville, A. (2010). Jewish Refugees from Germany and Austria in Britain, 1933-1970: Their Image in AJR Information. Vallentine Mitchell.

Hitler, A., Johnson, A. S., & Chamberlain, J. (1923, 1939). Mein kampf, complete and unabridged, fully annotated. Reynal & Hitchcock.

Kochavi, A.J. (2001). Post-Holocaust politics: Britain, the United States, and Jewish refugees, 1945-1948. University of North Carolina Press.

Kranzler, D. (1976). Japanese, Jews and Nazis: The Jewish refugee community, 1938-1945. Yeshiva University Press.

Kushner, T. (2002). “Pissing in the wind?” The search for nuance in the story of Holocaust “Bystanders”, in “Bystanders” and the Holocaust: a re-evaluation, D. Cesarani and P.A. Levine (eds.), 57-76. Frank Cass.

Kushner, T. (1994). The Holocaust and the liberal imagination: A social and cultural history. Blackwell.

Kushner, T. (1989). Persistence and Prejudice: Antisemitism in British society during the Second World War. Manchester University Press.

London, L. (2001). Whitehall and the Jews, 1933-1948: British immigration policy, Jewish refugees and the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press.

Lorant, S. (1935). I was Hitler’s prisoner: A diary. G. P. Putnam’s sons.

Marrus, M. (1985). The Unwanted: European refugees in the twentieth century. Oxford University Press.

Michman, D. (1998). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans. Yad Vashem.

Moore, B. (1986). Refugees from Nazi Germany in the Netherlands, 1933-1940. Nijhoff.

Novick, P. (1999) The Holocaust in American Life. Houghton Mifflin.

Patt, A. J. (2020). Life in the Aftermath: Jewish Displaced Persons. In Laura Hilton & Avinoam Patt, Understanding and teaching the Holocaust (pp. 159–177). The University of Wisconsin Press.

Patt, A., Grossmann, A. Levi, L.G. and Mandel, M.S. (eds). (2019). JDC at 100: A century of humanitarianism, Wayne University Press.

Penkower, M. (1988). The Jews were expendable: Free world diplomacy and the Holocaust. Wayne State University Press. Ristaino, M. R. (2001). Port of Last Resort: The Diaspora communities of Shanghai. Stanford University Press. Rosenbaum, A. (2017), The safe house down under: Jewish refugees from Czechoslovakia in Australia, 1938-1944. Peter Lang Ltd. Rubinstein, W.D. (1997). The myth of rescue: Why the democracies could not have saved more Jews. Routledge.

Rutland, S.D. (1978). “The Jewish community in New South Wales, 1914-1939,” unpublished MA Thesis, University of Sydney.

Rutland, S.D. (1983). Take heart again: The story of the Fellowship of Jewish Doctors. Fellowship of Jewish Doctors..

Rutland, S.D. (2001), Edge of the Diaspora: Two centuries of JewishsSettlement in Australia. Holmes & Meier.

Sachar, A. (1983). The redemption of the unwanted: from the liberation of the death camps to the founding of Israel. St. Martin’s/Marek.

Sarna, J. D. (2004). American Judaism: A history. Yale Univ. Press.

Shain, M. (2015). A perfect storm: Antisemitism in South Africa 1930 – 1948. Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Sherman, A.J. (1994, 1973). Island refuge: Britain and refugees from the Third Reich, 1933-1939, (2nd edition). Frank Cass.

Szulc, T. (1991). The Secret alliance: The extraordinary story of the rescue of the Jews since World War II. Ferrar, Straus and Giroux.

Wajnryb, R. (2001). The Silence: how tragedy shapes talk. Allen & Unwin.

Wasserstein, B. (1979) Britain and the Jews of Europe, 1939-1945. Oxford: Institute of Jewish Affairs, Clarendon Press.

Wasserstein, B. (1999). Britain and the Jewish of Europe, 1939-1945 (2. Ed). Leicester University Press.

Wischnitzer, M. (1956). Visas to freedom: The history of HIAS. The World Publishing Company.

Wyman, D.S. (2007). The abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust 1941-1945. The New Press.

Wyman, D.S. (1985). Paper walls: America and the refugee crisis 1938-1941. University of Massachusetts Press. Wyman, D.S. (1968). Paper walls: America and the refugee crisis, 1938-1941, University of Massachusetts Press.

Teaching Resources

The Unwanted: Refugees, Migration and Resettlement

Click to view Teaching Resources for “The Unwanted: Refugees, Migration and Resettlement”

The Unwanted: Refugees, Migration and Resettlement

Students: please read and respond to this chapter from a free OER textbook on the Holocaust. Please write a short essay (parameters noted by the teacher); follow the three-topic writing prompts below. Please use academic writing style in your essays.

Rutland (2023) describes ‘unwanted’ post-war refugees and migrants who resettle in places including Australia.

- How does she describe post-war migrations (in the second part of her chapter)?

- How does she characterize the Displaced Persons Act of June 1948?

- How were refugees helped by the JDC and HIAS (organizations that continue to serve)?

- To explore more terms, students can use this online glossary

- Here is how to cite and reference our online textbook.

Teaching resource by Professor Michael Polgar, May 2023.

The ‘Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service’ excluded people who were Jewish and political opponents of the Nazis from all civil service positions. This law initially exempted veterans of World War I, some long-terms employees, and people with a father or son killed in action in World War I. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

“A conference convened by President Roosevelt in July 1938 to discuss the problem of refugees. While thirty-two countries were represented at the conference in Evian-les-Bains, France, not much was accomplished, since most western countries were reluctant to accept Jewish refugees.” Echoes and Reflections.

In 1938, Hitler threatened war unless the Sudetenland (part of Czechoslovakia bordering Germany, with an ethnic German majority) was surrendered to Germany. Britain, France, Italy, and Germany held a conference in Munich, Germany, on September 29-30, 1938, and agreed to German annexation of the Sudetenland in exchange for a pledge of peace from Hitler. Czechoslovakia, not a party to the Munich negotiations, agreed under pressure from Britain and France. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

“An enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and removed’” Wikipedia

“Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, in June 1941, is considered one of the largest military operations in the history of modern warfare. Germany and its allies assembled more than 3,500,000 troops for the attack.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

“The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was created at a 44-nation conference at the White House on November 9, 1943. Its mission was to provide economic assistance to European nations after World War II and to repatriate and assist the refugees…under Allied control. The US government funded close to half of UNRRA's budget.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

“President Harry S. Truman signed the Displaced Persons Act in June of 1948. The… DP Act seriously limited who was eligible to come to the US as Displaced Persons. The act created a very narrow official definition of a DP .....The act required people to receive medical clearance and secure sponsorship from an American citizen in order to come to the US." United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

"People whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship” Wikipedia