Aftereffects

Memorializing the Holocaust: Public Art, Collective Memory, and Upstander Education

George Dalbo

Why is There a Holocaust Memorial Here?

While driving from Wisconsin to Georgia to visit family, my partner and I stopped in rural south-central Tennessee to visit a Holocaust memorial. The memorial, which grew from ‘the Paper Clips Project,’ is located on the grounds of the middle school in Whitwell, a community near Chattanooga of roughly1600 people. The memorial seemed out-of-place, despite the well-known story of how this memorial was created in the late-1990s. It was the subject of a book, Six Million Paper Clips: The Making of a Children’s Holocaust Memorial (Schoeder & Schroeder-Hildebrand, 2004), and a documentary, Paperclips (Berlin & Fab, 2004).

Tennessee includes only a very small percentage of Jewish people and, while driving into the town through the mountains, we saw a lot of Confederate flags prominently displayed on front porches. I felt a noticeable and unnerving juxtaposition between a Holocaust memorial that explicitly calls for tolerance and a Confederate flag that is widely viewed and recognized as a symbol of hate (ADL, 2020).

The memorial’s most prominent feature is a wooden railroad car used to transport Jewish prisoners to concentration camps. This boxcar is now filled with 11 million paper clips that were collected by middle school students in the late 1990s and early 2000s to represent the roughly 11 million victims of the Holocaust and Nazi aggression, including six million Jews and five million others: Roma and Sinti, people with mental and physical handicaps, LGBTQ+ individuals, and political and religious prisoners. In addition to some information about the victims, the site signage and audio guide explicitly reference Christian themes and scripture. Such references seem less a representation of the victims and more a reflection of the collective identity and aspirations of the community of Whitwell. As my partner and I stood looking at the memorial, overwhelmed by its solemnity and the enormity of the task of collecting 11 million paperclips, as well as the incongruity of a Holocaust memorial in rural Tennessee, my partner turned to me and whispered, with a hint of incredulity in her voice: “Why is there a Holocaust memorial here?”

Given contemporary Americans’ temporal and spatial distance from the events of the Holocaust, one might wonder why there are so many Holocaust museums and memorials around the United States. While many of these museums and memorials are the result of efforts by local Jewish communities and Holocaust survivors who settled in the United States after World War II, some, like the memorial in Whitwell, are not. Over the last several decades, according to historian Peter Novick (2000), the Holocaust has been Americanized or become “an American memory” (p. 15). In other words, the Holocaust has become an important aspect of American history and collective memory. While museums and memorials are often designed as spaces to remember and honor the victims of the Nazi (National Socialist) regime and their collaborators, they also function as spaces to educate students and the public about the Holocaust, to represent and transmit American values to current and future generations. For many Americans, the single most important lesson from a study of the Holocaust is the crime of indifference, or the failure of individuals and societies to speak out and stand up in the face of injustice, persecution, and genocide (Schweber, 2004).

“Never again,” a phrase taken up as a vow against future mass atrocities in the aftermath of the Holocaust, has been Americanized to mean never again will individual Americans and the United States stand idly by in the face of persecution or mass violence. Thus, in addition to the history of the Holocaust, many U.S. museums and memorials seek to impart moral lessons for the visitors about the evils of intolerance and, especially, indifference and the necessity of awareness and action.

Memorials in the United States represent public consciousness and collective memory around the Holocaust, and they function as sites of public education to engender upstanders. Holocaust memorials often represent and reflect American society and values; many are designed to inspire and educate individuals and groups to stand up to injustice, persecution, and mass violence. As we examine a group of memorials, we define and discuss the concepts of Holocaust consciousness, collective memory, and upstander in relation to Holocaust memorialization.

Holocaust Consciousness and Collective Memory

From the early 1990s, with the opening of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington DC and the premiere of the academy award-winning film Schindler’s List in 1993, the Holocaust has been firmly established in the collective consciousness of the United States, including in popular culture and, especially, public education (Novick, 2000). Since the 1990s, the goals for Holocaust memorialization and education in the United States have shifted from earlier approaches that often focused on the uniqueness of the Holocaust and centered mostly victims’ experiences to more-recent lessons aimed at providing broader, universalized lessons around tolerance, democratic citizenship, and what it means to stand up against discrimination and mass violence (Dalbo, 2019).

This increase in public consciousness and education about the Holocaust has spurred the creation of dozens of Holocaust museums and memorials across the United States. Many of these regional museums and memorials have centered narratives of tolerance and citizenship education. Like the USHMM, which was designed as both a museum and memorial, many regional museums also serve as powerful memorial spaces. Similarly, many Holocaust memorials, like those that we will explore in Miami Beach, Florida and Boston, Massachusetts, feature robust websites with educational resources and on-site public and educational programming.

Museums and memorials have long served as sites for groups and nations to publicly remember and mourn their dead, celebrate their heroes and triumphs, and express and transmit their collective values, commitments, and desires. Memorials are less representative of the history of a particular society; rather, they often exemplify the collective memory of a nation. Collective memory is a term that represents the shared memories of a particular social or national group, such as Americans or Jewish Americans, that are passed from one generation to the next. Collective memory is often understood to be a significant aspect of a group’s identity and culture (Novick, 2000). Collective memory differs from historical narrative in that history is meant to be a complete and unbiased account of past events, while collective memory represents the past in ways that are partial and intertwined with a group’s values and biases. For example, in the United States, historical narratives, supported by evidence such as newspaper articles, attest to the fact that many, if not most, Americans were aware of the widespread discrimination and persecution of the Jews in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe (Papadakis, 2003). However, some individual and some American collective memories of the period insist that many or most Americans had no knowledge of the Holocaust until the news of the liberation of concentration camps in 1945. This lack-of-knowledge narrative is more aligned with an imagined, hopeful collective vision of the United States that erroneously suggests that had Americans known about the persecution and murder of Jews in the 1930s and 1940s; surely there would have otherwise been a tremendous outcry against the Nazis and an overwhelming outpouring of support for the Jews and other victims. It has also been common for Holocaust representations to show the United States in a singularly positive light as liberators of the Jews in 1945 while omitting any mention of American indifference or even the widespread antisemitism in the United States during or after the 1930s.

In addition to honoring the victims and liberators, Holocaust memorials have become a site for U.S. society to express collective hope and commitment to the spirit of “never again.” Memorials have often been erected in prominent public spaces such as parks and state capitol grounds to express a collective commitment to publicly speaking out and standing up through government action. Through explicit signage or their design, memorials frequently encourage visitors to reflect on their individual commitments to speak out and stand up against intolerance, discrimination, and mass violence. However, while serving a role as powerful public symbols, Holocaust memorials have also been the targets of hate crimes such as vandalism including antisemitic graffiti, reflecting that antisemitism that is still prevalent in contemporary U.S. society.

Bystanders and Upstanders

In the aftermath of World War II, with the liberation of the concentration camps in 1945, Nuremberg Trials in 1945-1946, and the televised trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, public attention was focused on the victims and perpetrators of the Holocaust. More recently, however, especially in terms of Holocaust education, the roles of bystanders and rescuers or upstanders have become central to studying or representing the Holocaust. Bystanders to the Holocaust are those individuals in Germany or Nazi-occupied territories who witnessed the persecution of Jews and others but did nothing to speak out against discrimination, deportations, and mass murder or act to, for example, hide Jews or help them escape. Unlike victims, perpetrators, or rescuers, most people in Germany and occupied Europe were bystanders. The term bystander may also refer to groups or countries, such as the Catholic Church or the United States, that did little or nothing to intervene before or during the Holocaust, despite the abundance of other or singularly nationalist perspectives.

In contrast, upstanders are those individuals, groups, or countries that did speak out and intervened on behalf of the victims of the Holocaust. The term upstander was coined more recently and promoted by genocide scholar and former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power, who spoke of “standing up rather than standing by” in the face of genocide (quoted in Zimmer, 2016). Upstanders were individuals that rescued victims during the Holocaust, including many recognized by Yad Vashem as “Righteous Among the Nations.” Unlike bystanders, upstanders account for a very small number of individuals or groups. It is precisely this sobering fact that far fewer people were upstanders than bystanders during the Holocaust that has led many museum and memorial designers to try to educate and inspire visitors to become upstanders in the future.

Chiune Sugihara Memorial in Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles, California (left). Sugihara was a Japanese official who helped roughly 6,000 Jews escape by providing transit vias for Japanese-occupied territories. Raoul Wallenberg Memorial in Los Angeles (right). Wallenberg was a Swedish diplomat who saved thousands of Jews in Nazi-occupied Hungary. Sugihara and Wallenberg are recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. (Author’s photographs)

Complicating the Bystanders-Upstanders Dichotomy

In the construction of historical narratives and collective memories, there is a tendency within U.S. education and popular culture towards representing historical figures as absolute heroes or villains. This happens with the Holocaust, where the perpetrators and bystanders are represented as the epitome of evil, and rescuers, such as Sugihara and Wallenberg, are represented as heroes. Van Kessel & Crowley (2017) wrote that such absolute and uncritical representation of individuals and groups can obscure our understanding of how and why people acted as perpetrators, bystanders, or upstanders during the Holocaust. Individuals, whether bystanders or upstanders, rarely acted alone; rather, they drew support for their action or inaction from networks of family, friends, and acquaintances. Likewise, both bystanders and upstanders made choices within the context of their circumstances. Additionally, it is important to recognize that, in some instances, the lines between bystander and upstander were blurred. In some very limited instances, people (and groups or countries) acted as upstanders, while, in others, those same people or groups may have been bystanders to the persecution and murder of European Jews and other groups. Expanding and complicating our narratives around bystanders and upstanders allows for deeper reflection on human nature, our circumstances, and our propensity to be bystanders or upstanders in the face of intolerance, persecution, and mass violence. Like other depictions, memorials offer a range of implicit and explicit messages about the Holocaust. As a visitor, it is important to critically analyze these memorials.

Analyzing Holocaust Memorials

In the United States in the twenty-first century, we are temporally and spatially distanced from the events of the Holocaust. However, memorials can serve as spaces to bridge the moral distance between contemporary American society and the victims of the Holocaust. “Moral distance” is a term that refers to the notion that one often feels less obligated to help those who are distanced, either physically far away or perceived as different from us (Singer, 1972). As with literature, memoirs, testimonies, art, and photographs, memorials can serve to humanize the victims of the Holocaust, evoke emotional responses in visitors, and push us to consider our positionality as a bystander or upstander to persecution and mass violence (both during the Holocaust and today). As you examine the four Holocaust memorials that follow, think about how the memorial’s creators have attempted to bridge the moral distance between the visitor and the events of the Holocaust. Additionally, consider how each memorial seeks to encourage visitors to contemplate their actions, educating and inspiring them to become upstanders.

Holocaust Memorials

What follows are photographs and a brief discussion of four Holocaust memorials from across the United States. These memorials are among the dozens of such memorials across the country. As you examine each memorial, keep this chapter’s central questions in mind: (a) How do these memorials represent American public consciousness and collective memory around the Holocaust? (b) How do these memorials function as sites of public education to engender upstanders? Additional critical thinking and discussion questions are provided for each memorial.

Liberation: Jersey City, New Jersey

While many Holocaust memorials in the United States include some reference to American soldiers who fought the Axis powers and liberated concentration camps, the memorial, Liberation, takes this as its central theme. Created in 1985 by Nathan Rapoport, a Jewish artist born in pre-WWII Poland, the memorial is in Liberty State Park in Jersey City, New Jersey, facing both the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. The memorial guide states:

Liberation depicts an American soldier carrying a survivor out of a concentration camp. The chests of the rescuer and rescued are joined, as if sharing one heart. The way that the survivor’s body is cradled in the arms of his liberator reflects comfort and trust. Liberation is a testament to the Americans who liberated the camps, and it is a memorial to those who perished. But it is also a symbol of the strong helping the weak, not persecuting them. It is a vision of one human being supporting another. It is a tribute to the best of America’s dreams: freedom, compassion, bravery, and–above all–hope. (U.S. Department of Defense, 1987)

Both the memorial’s subject and location highlight the United States as an upstander nation. The soldier comes to symbolize all American soldiers past and present, and the Holocaust survivor stands for the weak and oppressed all over the world. Unlike memorials that stress the importance of individual upstanders, Liberation highlights the role of the nation-state as upstander.

The pedestal reads:

Dedicated to America’s role of preserving freedom and rescuing the oppressed, this monument by Nathan Rapoport, of an American soldier carrying a World War II concentration camp survivor, was gifted to the State of New Jersey by the generosity of thousands of people of good will. May 30, 1985; Liberty Park Monument Committee. (Gobetz, 2008)

Discussion Questions:

- How does Liberation’s location near the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, represent the collective memory of the Holocaust in the United States?

- The soldier appears without a weapon. How does the artist’s decision to exclude a weapon impact how one views the monument?

The Holocaust: San Francisco, California

One of the most haunting and pedagogically evocative Holocaust memorials, San Francisco’s Holocaust Memorial, created by renowned sculptor George Segal in 1984, allows visitors to shift perspectives from perpetrator to victim to bystander, while contemplating what it means to be an upstander. Perched on a hill in Lincoln Park overlooking San Francisco Bay and the Golden Gate Bridge, the memorial consists of a large three-sided, open-roofed enclosure set into the hillside. Approaching the memorial, one sees a barbed-wire fence. A lone figure stands looking out with one hand placed on the fence. Behind him, additional figures are heaped together in a pile that forms the approximate shape of the Star of David. The life-sized figures were cast in bronze and coated in white plaster. According to Segal, the memorial was based on Margaret Bourke-White’s (1945) photograph, The Living Dead at Buchenwald, which showed survivors standing behind barbed wire (Center, 2020). Informational plaques are located out of view behind the rear wall of the memorial. Visitors to the memorial can stand outside the fence and see what appears to be a concentration camp. Additionally, visitors can walk into the enclosure to stand next to the lone figure looking out through the barbed wire and walk around the bodies. Thus, during a visit, one shifts perspectives from bystander to victim to perpetrator depending on where one is standing. Taking on the perspective of a bystander, victim, or perpetrator encourages self-reflection around one’s positionality in relation to historical and contemporary discrimination and mass violence.

Discussion Questions:

- The design encourages visitors to walk among the memorial. How should visitors engage with such memorials? How do you feel about visitors touching, taking photographs (or selfies), or picnicking near the memorial?

- The memorial was based on Bourke-White’s photograph, The Living Dead at Buchenwald. What are the differences between the memorial and the photograph?

- Segal’s friends posed for the casts of the man behind the fence and the dead bodies. Thus, the figures are not emaciated like the survivors and victims of the concentration camps. How does this change how one experiences the memorial?

New England Holocaust Memorial: Boston, Massachusetts

Located in downtown Boston, Massachusetts, the New England Holocaust Memorial opened in 1995. It consists of six glass towers, one for each of the Nazi death camps: Auschwitz, Bełżec, Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibor, and Treblinka. The towers represent both crematoria chimneys and menorah candles. Visitors to the memorial walk underneath each tower as vents in the ground emit steam. The glass panels are inscribed with a series of numbers representing the roughly-six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust. In the surrounding park space, several stone monuments feature quotes and poems from survivors and liberators. The interactive and highly sensory experience of visiting the memorial invites people to reflect on the victims’ humanity, as well as their own. The uncomfortable experience of walking through the steam reminds visitors that they are alive, encouraging them to consider their position in relation to the persecution and murder of the Jews in the Holocaust.

New England Holocaust Memorial: Boston, Massachusetts

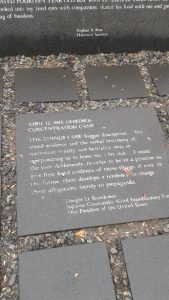

Text from plaque on right reads:

April 12, 1945: Ohrdruf Concentration Camp: “The things I saw beggar description … The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty and bestiality were so overpowering as to leave me a bit sick… I made the visit deliberately, in order to be in a position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to ‘propaganda.’”

Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force

34th President of the United States.” (Author’s Photographs)

Discussion Questions:

- How might the interactive and highly sensory experience of the memorial impact a visitor?

- How might the inclusion of Eisenhower’s quote contribute to the pedagogical aspects of the memorial?

Holocaust Memorial: Miami Beach, Florida

The Holocaust Memorial in Miami Beach, Florida was dedicated in 1990. The vast memorial complex features numerous sculptures and informational panels. According to the designer, Kenneth Treister, the memorial is “a series of outdoor spaces in which the visitor is led through a procession of visual, historical and emotional experiences with the hope that the totality of the visit will express, in some small way, the reality of the Holocaust” (About the Sculptor, 2016). The memorial’s focal point is undoubtedly a roughly four-stories-tall bronze sculpture of an arm reaching out of the center of the memorial space. The arm, tattooed with a number from the Auschwitz Concentration Camp, is covered with nearly life-size figures of emaciated men, women, and children, who cling to the arm, climbing upward, writhing in agony, and reaching out for help. The memorial’s main pedagogical approach is to trigger an emotional reaction in the visitor and, perhaps, foster a conviction to stand up amid such suffering.

Discussion Questions

- How does the sheer scale of the structure influence how visitors interpret the memorial?

- How might an artist or educator use the emotional response of the visitor to engender upstanders? What might the benefits and limitations of such an approach be?

Iowa Holocaust Memorial: Des Moines, Iowa

Iowa’s Holocaust Memorial is located on the grounds of the Iowa State Capitol Building in Des Moines. Constructed in 2013, it consists of four aluminum panels that display engraved images and text. According to its website: “The memorial enshrines the lessons of the Holocaust: to protect democracy, to take action in the presence of evil, and to teach one’s children by example to respect people different from oneself” (Iowa Holocaust Memorial, 2020). These lessons are evident in much of the memorial’s text. One panel prominently includes the phrase, “love thy neighbor,” a direct reference to Christian and Jewish scripture. Other panels highlight the role of Iowan soldiers in the liberation of the concentration camps. Yet another panel discusses the Jewish Holocaust survivors who settled in the state:

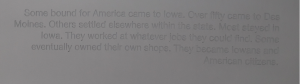

Some bound for America came to Iowa. Over fifty came to Des Moines. Others settled elsewhere within the state. Most stayed in Iowa. They worked at whatever jobs they could find. Some eventually owned their own shops. They became Iowans and American citizens.

Such text seeks to engender attitudes of tolerance and acceptance for (im)migrants and refugees . When located in view of the Iowa State Capitol building, the memorial becomes a reminder to legislators of their duty to uphold the values and commitments of the United States as an upstander nation.

Plaque reads:

“Some bound for America came to Iowa. Over fifty came to Des Moines. Others settled elsewhere within the state. Most stayed in Iowa. They worked at whatever jobs they could find. Some eventually owned their own shops. They became Iowans and American citizens.” (Author’s photograph)

Discussion Questions:

- What messages might the Iowa Holocaust Memorial designers have intended when selecting the capitol grounds as the location for the memorial? Who is the intended audience?

- Given its location on the capitol grounds, what ideas does the Iowa Holocaust Memorial communicate about the role of the Holocaust and Holocaust education in a pluralistic democracy?

Conclusion: What do Holocaust Memorials Say About Us?

Often, coverage of the Holocaust ends with the liberation of the concentration camps in 1945 or, in some cases, the subsequent Nuremberg Trials. We can also consider how the history and collective memories of the Holocaust have developed in the intervening years. Museums and memorials provide a way for us to examine, among other things, the collective memory of the Holocaust. Holocaust scholar James Young (1995) wrote: “Indeed, the further the Holocaust recedes into time, the more prominent its memorials and museums become” (p. 1). Museums and memorials also become important spaces for societies to express their collective values and commitments and preserve them to educate and inspire future generations.

Holocaust memorials in the United States often express that which is best about Americans and America: a commitment to speak out and stand up in the face of tyranny, injustice, persecution, and crimes against humanity. Many of these same memorials, however, may not address the failure of the United States to do more to prevent the Holocaust as it unfolded in the 1930s and the 1940s. Similarly, Holocaust memorials, like the memorial in Whitwell, Tennessee, may exist in uneasy relation to the historical and contemporary injustices within U.S. society, such as slavery and white nationalism, that have yet to be fully acknowledged or addressed. Nonetheless, the Holocaust memorials that occupy the physical and memory landscape of the United States offer hope for inspiring future generations of upstanders.

References

About the sculptor (2016). Holocaust memorial: Miami Beach.

Berlin, E., & Fab, J. (2004). Paper clips [Motion picture]. Miramax Films.

George Segal monument. (2020). Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, University of Minnesota.

Dalbo, G. (2019). The Holocaust as Metaphor: Holocaust and Anti-Bullying Education in the United States. In A. Ballis, M. Gloe Holocaust Education Revisited (pp. 63-85). Springer. Online ISBN: 978-3-658-24205-3.

Gobetz, W. (2008). NJ – Jersey City: Liberty State Park – Liberation. Flickr

Hate on display: Hate symbols database. (2020). Anti-defamation League. ADL

Iowa Holocaust memorial. (2020). Iowa council for Holocaust education. Iowa Holocaust Memorial

Novick, P. (2000). The Holocaust in American life. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Papadakis, A. M. (2003). Why Didn’t the Press Shout?: American & International Journalism During the Holocaust. KTAV Publishing House.

Schroeder, P. W., & Schroeder-Hildebrand, D. (2005). Six million paper clips: The making of a children’s Holocaust memorial. Kar-Ben.

Schweber, S. (2004). Making sense of the Holocaust: Lessons from classroom practice. Teachers College Press.

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, affluence, and morality. Philosophy & public affairs, 1(3), 229-243.

U.S. Department of Defense Guide to Observances, Days of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holocaust (1987). U.S. Government Printing Office.

van Kessel, C., & Crowley, R. M. (2017). Villainification and evil in social studies education. Theory & Research in Social Education, 45(4), 427-455.

Young, J. E. (1995). The changing shape of holocaust memory. American Jewish Committee.

Zimmer, B. (2016, September 9). How high-school girls won a campaign for ‘upstander.’ Wall Street Journal.

The notion that one often feels less obligated to help those who are distanced, either physically far away or perceived as different from us. Singer, P. (1972). "Famine, affluence, and morality," from Philosophy & public affairs, 1(3), 229-243. Wikipedia

The notion that personal values, views, and location in time and space influence how one understands the world... Consequently, knowledge is the product of a specific position that reflects particular places and spaces. Encyclopedia