Settings

Camps and Ghettos in Europe during the Holocaust

Michael Polgar

Learning Objectives:

- Readers will learn how Nazi camps and ghettos were tools of the state used to persecute Jewish and other groups of people during the Holocaust.

- Readers will learn about concentration camps, including death camps, in Nazi-occupied Europe during the Holocaust

- Readers will learn details about ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during the Holocaust

Teaching Resources:

- iWitness has recordings of Holocaust and other genocide survivors, along with both curricula and opportunities to design customized curricular materials.

- Facing History and Ourselves has excellent online curricula for teaching the Holocaust and Human Behavior.

- Echoes and Reflections inspires educators and students to learn about the past and build a better future.

The Holocaust developed in a series of stages, from 1933-1945, starting with categorization, and including definition-by-decree (Berenbaum, 1997; Hilberg, 2003). In 1935, the Nuremberg laws divided, categorized, and set the parameters for systemic exclusion of Jewish Germans. People were defined as Jewish according to descent, creating a form of racialized antisemitism. Nazi law and practice thereafter denied rights and persecuted people classified as belonging to a Jewish “race,” which involved having a specific heritage that defined Jewish “blood.” Nazi laws also established other arbitrary categories for the basis of state-supported discrimination. Government officials, agencies, and many collaborating groups supported growing and expanding systems of general, political, and specifically antisemitic persecution.

Antisemitic policies in the early and mid-1930s initially involved encouraging Jewish emigration (Dwork & Van Pelt, 2009). Throughout their authoritarian rule, Nazis systematically expropriated resources from Jewish and other persecuted populations (Hilberg, 2003, p. 94). Once group membership was established, Nazis concentrated in prison camps members of persecuted groups, including political opponents, people defined as Jewish, and a variety of other populations. Concentration forced Jewish populations and others into camps and ghettos; this created the sites of dehumanization and murder that are the foci of historical reflection and of this chapter. Before and especially during the second world war (1939-45), the Nazi authoritarian government murdered millions of Jewish people and members of other persecuted groups, both within Germany and in the many nations Nazis annexed and occupied.

Tools of the State

Nazi concentration camps were tools of the state designed for persecution. Megargee (2020, p. 95) notes that there were about two dozen types of camps within a system that grew in number into thousands of sites and sub-camps. Their interrelated purposes included detention, punishment, labor, and racial eugenics. These camps, along with Nazi ghettos, were ultimately used for genocide.

Jewish people and communities were the focal target group during the Holocaust, while people with disabilities, communists, Roma and Sinti people, Jehovah’s Witnesses, gay men, Afro-Germans, and others were also systematically targeted and often murdered. Stone (2017) also notes that Nazis designed another and different kind of specialized and exclusive paramilitary training camps for those privileged by racism and discrimination, such as Nazi youth communities. The numbers and varieties of camps and ghettos used for Nazi persecution (mass or industrialized murder of innocent people) are staggering, filling multiple volumes of an encyclopedia (Megargee, 2009).

Teaching Resources:

- Echoes and reflections includes many resources about camps and ghettos, including summaries in it video toolbox.

- The US Holocaust Memorial Museum has excellent resources on the Holocaust, including online resources for students and teachers.

All Nazi concentration camps and ghettos, regardless of type, served to detain, controlling space and time. Even so, detention of populations and groups, which as publicly rationalized by false and dehumanizing propaganda, was not the sole or primary purpose of these prisons. Over time and in phases (1933-39, 1939-42, and 1942-45), camps were used to detain, deter opposition to the state, force labor (enslave), extort personal and real property, and ultimately to contribute to a process of industrial mass murder, which later became known as a genocide. Some people and groups, including prisoners of war (POWs), were selected for forced labor and survived, at least for a time. Even so, camp detention was often lethal as well; 3.3 million Red Army (Soviet) prisoners died in Nazi camps, representing approximately 58% of all Soviet prisoners, along with 2 to 3% of US and British POWs (Megargee, 2020, p. 97).

Forced labor by enslaved prisoners was a primary purpose of the camp system, with thousands of camps supporting the German war economy in every sector, involving major German corporations (some of which remain operational, popular, and profitable). Forced laborers, including POWs, provided the economic benefit of offsetting labor shortages created by mass conscription of German men into the Nazi armed forces. Forced labor also masqueraded as reform for people-deemed-unworthy, suggesting that discipline and work would promote freedom. Cruel irony and strategic deception met prisoners at the gates of many camps, including Auschwitz: ARBEIT MACHT FREI, or “Work will set you free”. Work was a means of punishment and control, exhausting prisoners to death, while at the same time educating others in the trades. For example, The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz (Geve & Inglefield, 2021) documents a brick-laying school for boys. Jewish prisoners were often subject to harsh and dehumanizing punishment; all were subject to persecution and control. Punishments were frequent, cruel, and mundane, including starvation, abuse, torture, and executions.

Nazis and their collaborators imprisoned political, social, national, and ‘racial enemies,’ persecuting ‘racial enemies’ (Jewish people specifically) most harshly. Punishment was also cruel and unusual for ‘political enemies,’ such as communists, socialists, and conscientious objectors to Nazi ideology. From the beginning of Nazi rule in 1933, political prisoners were incarcerated without due process in police barracks and in early camps like Dachau, the first Nazi concentration camp (Stone, 2017, p. 403). Racist dogma translated into unequal treatment in many ways, For example, Slavic political prisoners (including Poles) were treated more harshly than western European prisoners. Some ‘Germanic’ children in occupied nations, orphaned or separated from their families, could be adopted and treated as human; other children were routinely mistreated and even subject to medical experimentation to the point of murder (Heberer, 2011).

Over the course of twelve years of Nazi power, camps and ghettos grew in number and size, creating evolving and extensive systems to support expulsion, detention, forced labor, and ultimately annihilation. The interior conditions were dehumanizing, giving rise to a range of degrading processes, including disease and death, suffering and starvation. Camps were regimented; prisoners who were not murdered by initial selections at death camps were called not by name but by assigned numbers (which were tattooed on their arms at Auschwitz). Numbered prisoners were subject to roll call morning and night, a process that could involve selections for murder of the infirm or undisciplined, people deemed unfit for labor and survival. Camp barrack assignment involved segregation by sex, national origin, ethnicity. No personal belongings were allowed in most camps; food and clothing were minimal. Women were mistreated and medical care was virtually absent (Lengyel, 2000).

While interior conditions in camps and ghettos varied widely, both over time and by location, some camps were particularly harmful while others had special functions. In addition to the six killing centers in occupied Poland, there were camps for people and groups in transit. The Holocaust required many evolving Nazi policies that incorporated, compensated, and strained German railway systems during wartime (Hilberg, 1985). “Model camps,” in particular Terezin (nearby Prague), were set up and on occasion ‘dressed up’ to mollify and deceive visiting international group delegations (such the International Red Cross). Because it could maintain cultural activities, Terezin provided the location for a short Nazi propaganda film, misrepresenting life in detention to hide cruel and inhuman truth. Camps and ghettos were sites of mass harm, where people suffered in what one historian called a ‘tide of death’ that swamped central Europe and European Jewry (Yahil, 1991, p. 359).

Teaching Resources:

- The Defiant Requiem Foundation has educational materials for teaching about the Holocaust and specifically about Terezín Ghetto.

- The Jewish Partisans Educational Foundations has high-quality e-learning resources that elaborate forms of resistance during the Holocaust.

In the early stages during the 1930s, there was usually no veil of secrecy about the presence and purposes of concentration camps, which were at times featured in Nazi propaganda. This stands in contrast to the latter and infamous death camps, which were initially a secret Nazi operation that soon became an open secret (Bergen, 2016). In the 1940s, mass murder was discussed in distorted terms with imperial language (Klemperer & Brady, 2006), for example as the “final solution” to the “Jewish Problem.” The early camp system was harmful but less lethal, an “ever-expanding system of extra-judicial system of exclusion and incarceration” (Stone, 2017, p. 35). The earlier stages of the camp system were in the news, both nationally and internationally, in real-time journalism and scholarly analyses. One man’s unjust experience of camp life was described by Hungarian Stefan Lorant (Lorant, 1935) in a best-selling book published in the United Kingdom. Camps were microcosms of totalitarianism, described by some as laboratories of violence. Camps were, especially once run by the SS, ‘a state within a state,’ with their own rules, including systems of terror, torture, and murder.

The killing centers, sites of mass murder, had daily routines. Prisoners who were retained after selections were awakened very early (often before dawn), made ‘beds’ of straw, leaving barracks quickly for line up in the dark. There were few facilities for washing or what we now call using the toilet. There was no soap or towel, little cold water, limited or no time to clean one’s body. After roll call, work groups were assembled and either marched or otherwise transported to sites of what was usually hard manual labor. To ‘motivate’ or speed up daily routines and forced labor, individuals were publicly beaten up, tortured, and killed to ‘teach’ inmates their roles and responsibilities (Bauer & Keren, 2001). In women’s barracks, pregnancy and childbirth were forbidden and would usually lead to murder of both mother and child (Lengyel, 2000).

Ghettos

The idea of a ghetto has developed over centuries. Historically, the initial location called a ghetto in the 1500s was a segregated Italian (Venetian) neighborhood for Jews that included a copper factory. In the 19th century, Jewish emancipation in Europe temporarily led to the elimination of Jewish ghettos. Then, Nazi-ordered displacement of European Jews created a new generation of ghettos in Europe. In the 1930s, ghettos of African Americans in the US, marked by restrictive housing covenants and coercion, developed into forms more familiar to modern readers. A system of discrimination that W.E.B. Dubois had observed both in the US and in Europe was re-established by Nazis to detain Jewish people in occupied eastern Europe (particularly but not only in Poland) starting shortly after the outbreak of the War (Duneier, 2016).

The idea to establish ghettos during a wartime emergency was raised in October 1938 by Nazi leader Hermann Goring. He viewed a process of removal through forced emigration of all Jewish populations as difficult and expensive (Dean, 2010). Reinhard Heydrich ordered ghettoization of Jews in all annexed or occupied territories, segregating Jews and concentrating them in delimited areas near rail lines. Large urban ghettos housed numbers up to six figures; medium-sized and smaller ghettos were diverse and widespread. Ghettos operated from periods of months or years, often falling into disuse after ‘liquidation.” The creation and later emptying of Jewish ghettos took place gradually and during the war.

Thousands of ghettos of varying size and type were created in many occupied locations. Ghettos were rationalized using reasons that were ideological, economic, and related to health and security (Dean, 2010, p. 341). Ghettos were seen by German Nazis as a source of labor and production, a form of destruction through attrition (producing greater ‘racial hygiene’), a source of financial gain through extraction of Jewish goods and assets, and a form population concentration, which aided the military as it marched east to widen Germany’s empire. Some ghettos were surrounded by fences or walls, but not all. In the Baltic states, they were often transit locations holding people for merely days or weeks before annihilation (Dean, 2010).

Differences among ghettos by location and region are traced in part to the fact that Heydrich’s order of 21 September 1939 had no specifications except that Jewish resident councils, Judenraete, were forcibly obligated to manage each ghetto’s internal decisions, including the horrific task of selecting who would fill quotas for transits to unknown and foreboding locations, which were often suspected to be sites of mass destruction. None of the Jewish councils made choices that were not ordered or constrained by Nazi German authorities (Hilberg, 2003). Some resistance grew from within and beyond ghettos, with partisan groups growing in part from people escaping the ghettos.

Resistance to Nazi persecution, too often minimized in historical accounts of the Holocaust, was at best exceedingly difficult, but did take place at many points and in many ways during the Holocaust. Among the forms of resistance, not always recognized by post-war authors or audiences, were forms of spiritual (unarmed) resistance; to maintain dignity or morale (through culture, prayer, hope, and education) was a form of resistance to Nazi persecution. Armed revolts took place in many locations, within ghettos (including Warsaw and Vilna) and camps (including sites of murder at Sobibor and Auschwitz). Resistance could be collective or individual, open or (more often) clandestine, and it was limited or hampered by Nazi threats-of-reprisal to both families and communities. Revolts and rebellions took place, often without support from the general (non-Jewish) public, most often in western European locations (Bauer & Keren, 2001).

High rates of morbidity and mortality in the ghettos were related to their increasingly horrific conditions. In the Polish capital of Warsaw, the pre-war Jewish population represented about 30% of the city. Mistreatment was not new to this community; waves of discrimination were documented back to 1500s. The Nazi occupation of Warsaw in 1939 and punishing deprivations led to both a Jewish exodus and large-scale ghettoization. The Warsaw ghetto was decreed in October and walled off in November 1940 (Laqueur, 2001). In the Warsaw ghetto, deaths (years prior to population decreases from ‘liquidation’ and uprising) represented about 10% of 450,000 registered Jews in 1941 (Dean, 2010). Disease, overcrowding, and starvation were widespread and well-documented across occupied lands. Ghettoization eroded networks of support, pressuring support structures and many Jewish families, as well as individuals. For women, ghetto-related strain included deprivations of food, health care, and other necessities. Gendered inequalities were documented by witnesses including Cecilya Slepak, a Jewish journalist in the Warsaw ghetto (Ofer & Weitzman, 1998).

While most of the surviving accounts come from male witnesses to the variations in ghetto life, feminist historians help us see women doing and describing important relief and other types of ghetto work. Respected women include author Rachel Auerbach, one of a few surviving members of the clandestine Warsaw ghetto resistance organization Oneg Shabbat or “sabbath delight”. While Nazis ordered that women be excluded from Jewish Councils, women performed important roles in health care, education, and other forms of social welfare (Ofer & Weitzman, 1998, p. 29). Women were also instrumental leaders to the underground resistance movements in ghettos (Batalion, 2020).

Ghettos were established in Nazi-occupied nations, including Poland, Baltic nations of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, Bohemia and Moravia, Romania, and later Hungary. Maps show extensive systems of ghettos. The Kovno, Lithuanian ghetto was a major site of cultural destruction and religious persecution (Bauer & Keren, 2001). In Germany, ‘Jewish Houses’ were sometimes created and concentrated in neighborhoods, as temporary locations prior to longer-distance deportations. Of course there are also effects on the lives and minds of segregated and persecuted groups and individuals, which have been called the “social and psychological ghetto” (Kaplan, 1999).

In 1939, a Nazi lawyer named Dr. Ludwig Fischer was appointed governor of the Warsaw district and thus overseer of occupied Warsaw and its ghetto, created through a brutal round-up of Jewish residents. At that time, he wrote about the Warsaw ghetto: “the Jews will croak from hunger and misery. There will be nothing left of the Jewish problem but the cemetery.” Four years earlier in September 1935, Fischer had been a leader among the 45 select Nazi lawyers who visited the US to observe one example of national laws promoting systemic racial exclusion. While the US became an ally and heroically defeated Nazism during the war, racism and white supremacy had been part of the Nazi’s American model (Whitman, 2017). Eliminationist antisemitism and other forms of racism outside of Germany thus influenced both ghettoization and the Holocaust more generally.

Ghetto formation from the autumn of 1939 to the autumn of 1941 followed a series of three types of expulsions. Jews and other Poles were taken from west to east, Jews and Roma were taken from the occupied or incorporated ‘Protectorate’ territories to the administrative area called the General government, and these groups were also into the other incorporated territories. Annexation expanded the scope of antisemitic German segregation. Nazi Hans Frank ordered in November 1939 that all Jews over age 12 wear a white arm band marked with a star of David, though some regions ordered people to sew and show the familiar yellow star on their outer garments. Many prohibitions that limited freedom and rights in Germany, such as free movement, spread east during wartime occupations of nations (Hilberg, 2003, p. 216-218).

Concentration Camps

Stone, as noted, defines a concentration camp as “an isolated, circumscribed site with fixed structures designed to incarcerate civilians” (Stone, 2017, 4). Thousands of Nazi concentration camps were constructed and operated as centers of persecution throughout Nazi-occupied Europe (Wachsmann, 2015). Not the first or only historical instance of concentration camps, Nazi camps came in many types, forms, and sizes. Like all concentration camps, they were designed to remove populations or groups from a state in crisis, specifically targeting groups of people who were represented as or perceived to be traitorous, dangerous, or diseased. These ‘problematic’ population designations were false and exaggerated by both propaganda and pseudoscientific eugenics. Dangers or diseases posed by Jewish people were rooted in antisemitic myths and blatant lies. Definitions of ‘traitorous behaviors’ were expanded to the point where free expression and other human rights were denied any groups that did not obey the Nazi party line; even children’s organizations and choirs excluded Jewish members and others through a Nazi policy of coordination, which was part of the ‘social revolution’ in mid-1930s Germany (Bergen, 2016).

Dachau was the first Nazi concentration camp; it was opened near Munich Germany. It was the longest running Nazi camp and operated from 1933 -1945 (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). Dachau focused on detaining and imprisoning political dissidents without any semblance of due process. Dachau and its political prisoners were widely publicized in the newly nationalized Nazi press as part of a multi-year effort by propagandist Joseph Goebbels; the Nazi state-controlled press focused on presenting both a singular Nazi party line and degrading images of those deemed dangerous to the new and future state (Kaplan, 1999).

Dachau was commanded by Theodor Eicke after July 1934, as appointed by Heinrich Himmler. After Nazi purges of the police forces, Himmler and Eicke created the first camp inspectorate (IKL), which became the central administrative body for the camp system (Orth, 2010). Hitler thereafter reorganized the camps, including camp guards within German military operations (under authority that was separate from the judiciary). Camps thereafter fell under the authority of the newly powerful Schutzstaffel or “SS”, initiating a new era of more singular control that included a consolidated camp system, starting in 1935. This system expanded to cover a large part of the continent. Recent innovations allow scholars to geo-visualize more than 1,100 SS camps using historical geographical information systems. Such modern applications of information technologies improve our understanding and visualization of locations and stages in ghetto and camp system development (Knowles & Jaskot, 2014).

Before the onset of war, several groups of people were incarcerated in camps by Nazi policies. A first group of political prisoners (called ‘political criminals)’ included communists, Jehovah’s witnesses, ‘undesirable’ Christian clergy, purged Nazis. A second group of ‘asocials’ included “habitual criminals” and sex offenders. The third and largest group became those Jewish people who were subject to large-scale police actions and marched into imprisonment (Hilberg, 1985).

The growth in numbers and functions of camps from 1937-38 was part of preparations for an imperialist and expansive war, which would itself scapegoat, and target people falsely cast as political, social, or racial threats. The Kristallnacht or “Night of [Broken] Glass”, was a pogrom designed to increase pressure on Jews to emigrate. History has shown it was an organized police-riot that included sweeping some 30,000 Jewish people into concentration camps, not a German national uprising (Dwork et al., 2002). Property was thereafter extorted from some of these prisoners as the price of release from camp imprisonment. During and after this period, the Nazis also turned forced prison labor from a relatively pointless exercises into profitable and wartime enterprises (Orth, 2010, p. 365).

By the onset of war in 1939, targeted human populations included a variety of Jewish and non-Jewish groups, particularly all people of all nationalities defined as Jewish by the Nazi race laws of 1935, ethnically Roma (Sinti) people, and Afro-Germans. Public memory of the Romani Holocaust is growing and is now described as the Porajmos which translates as “devouring” or “destruction” (Romani). Marginalization and persecution of Roma and Sinti people occurred both before and during the Nazi period. Population groups racialized by Nazi laws and policies were defined as threatening the ‘racial purity’ of a “German folk” (ignoring the fact that most were German nationals, some even military veterans of the First World War). The Nazis encouraged, institutionalized, and supported many forms of eugenic racism and other eugenic pseudoscience (Bergen, 2016).

A second expansion of the camp system corresponded to Nazi-initiated World War II and German territorial annexations, which triggered migrations and millions of deportees. Eicke’s inspectorate could not keep up. After 1940, SS and police leaders established and expanded camps, including the infamous killing centers. Camps were thereafter consolidated again; the centralized systemic network was managed by Oswald Pohl, a former Nazi naval paymaster who lived near Dachau, and his SS Economic-Administrative Main Office (Wachsmann, 2015). Pohl then moved away from this Main Office and established two new bureaucracies and offices that managed SS camp and labor enterprises. The state office (the HHB, which handled German state funds) was created separately from a business venture that was the VWHA. Hilberg notes this gave the camps ‘an economic accent,’ appealing to those who were focus on earning profits during wartime (Hilberg, 2003).

In 1944, Nazi leader Himmler received a report from Pohl that detailed major expansions in the camp system and network, its international jurisdiction, and the consequent growth in the forced labor pool. In the system of camps, Pohl and the VWHA had a forced labor pool that expanded more than twenty-fold, from an estimated 21,400 in 1939 to over 524,000 people in 1944 (Hilberg, 2003). Later in 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights would include Articles Four and Five, which prohibit slavery and degrading punishment respectively, along with Article Nine, which prohibits arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

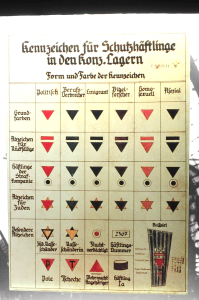

Camps were planned and built using forced and other labor; subsequently the numbers of prisoners quadrupled in the first three years of the War, bringing many new prisoners into the system. The initial prewar and now familiar camp system of signs, markings, and badges for ‘detainees’ included color-coded triangles and letters, shown in Figure 1. This system remains an enduring visual reminder of classifications based on pseudo-scientific, hierarchical, and racial criteria, including continuation of rules that obligated all Jewish people to wear visibly a star of David. Conditions in camps worsened and death rates increased during the initial and throughout the wartime period (Orth, 2010, pp. 366-67).

In 1941, with the German invasion of the former Soviet Union, new camps in what Nazis called ‘the east’ were opened, many for wartime purposes, including death camps and camps confining Soviet POWs. These included the death camp at Chelmno, operational in Poland in December 1941. Many POWs were simply murdered, and millions of incarcerated POWs would be dead by the end of the war, in addition to millions killed in battle. In this period, as the ‘Holocaust by bullets’ was concurrently underway (Desbois, 2009), the camp system became administered by the SS’s Business Administration main office (Acronym: WVHA). Industrial mass killing was systematic, first by bullets and then by gas in death camps.

Some of the six Nazi death camps in occupied Poland (Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka) were built in 1941 (Stone, 2017), marking a transition from Nazi policies of mass exclusion and incarceration to the “final solution” policy of mass murder (later to be described as genocide). Sites of murder (death camps) represent a sixth and final stage of the Holocaust (Berenbaum, 1997; Hilberg, 2003). The cruel calculations that led to this final stage of destruction accounted for the economic savings of mass-murder-by-gassing, the growing psychological impact on Nazi shooters, and shifting wartime strategies.

Death Camps

The Wannsee Conference near Berlin in January 1942 was a small lakeside meeting of Nazi leaders. Reinhard Heydrich signed the Wannsee protocol, establishing new methods for genocide (code named the “final solution”) that would be used for destruction in “the east” (Dwork & Pelt, 1996). Methods used in prior years to murder upwards of one million human beings were found to be impractical for the goal of destroying all 11 million Jewish people in occupied lands. As noted, mass shootings (Desbois, 2009) were recognized to be more expensive and demoralizing, and mass killings in the west could provoke stronger opposition (Bauer & Keren, 2001). A “final” and “total solution” to the “Jewish question” would require new plans and new operational measures. “Evacuation to the east” and subsequent genocide was established by this protocol. The Nazi plan to make a German empire that was “free of Jews” would no longer do so through encouraging Jewish emigration; industrial murder with poison gas would be scaled up, requiring new or newly developed facilities and operations.

In 1945 and thereafter, witnesses of the gruesome end-stage of Nazi crimes were shocked to see unforgettable and horrific forms of dehumanization. Seeing the carnage in Nazi camps spurred liberator US General Dwight D. Eisenhower to remark that the world must see the Holocaust and ‘never again’ allow such atrocities. The sites of mass murder created by Nazi policies and practices beggar description. “Industrial death factories” (Snyder, 2022) and assembly-line killing centers are two vivid ways to describe these places. It seems appropriate to use the active voice in describing this planned process of mass murder, since perpetrators of mass crimes should not be absent from their deeds (Goldhagen, 1997). We minimize and distort the Holocaust if we timidly or simply suggest that “many people were killed,” as if perhaps the killers were unknown or acting repeatedly and without intention.

Hilberg (1985 and 2003), excerpted by Dwork (2002), makes it clear:

Camps were the collecting points for thousands of transports converging from all directions… As the transports turn back empty, their passengers disappeared inside. The killing centers worked quickly and efficiently. A man would step off a train in the morning and in the evening his corpse would be burned, and his clothes packed away… a whole army of specialists played their part… (Killing centers were) unprecedented. Never before in history had people been killed on an assembly line basis… no prototype… it was a composite institution: the camp proper and the killing installations in the camp. (Hilberg, 1985, p. 863).

Six death camps (sites of mass murder) were created and operated by Nazis and their accomplices. Three of these sites of murder were implemented in the fall of 1941 as part of Nazi Operation Reinhard. The leadership and camp guards served in a variety of SS and Wehrmacht or “Military”, ranks. Some undesired jobs like those in a Sonderkommando or “special command unit”, were performed under duress by forced (often Jewish) laborers. After millions has already been murdered in mass shootings and buried in mass graves (Desbois, 2009), Nazi planners had understood that there were disadvantages to simply shooting and disposing of large numbers of people. Methods employed by the Einsatzgruppen or “action squads”, in the annexed “east” required supplies and diversion of weapons and materials, which themselves required increased military production. There were also Nazi concerns about shooters who could become demoralized and alcoholic (Westermann, 2021).

In the early 1940s, before the Wannsee Conference, many Nazi mass murders were carried out by forcing human beings into gassing vans, then driving these vans until all prisoners inside were asphyxiated by carbon monoxide exhaust fumes that had been directed back into the vans. This combination of transportation and killing methods left corpses that might need to be burned, buried, or both. Such methods were developed by the T-4 secret operation to gas groups of hospitalized people with disabilities (Kuntz & United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2008). The use of the pesticide Zyklon-B proved easier to administer, especially in death camps designed for this purpose. Thus, in Auschwitz, fake “showers” were sealed death chambers where Nazis dropped poison gas canisters into protected spaces within wire columns.

In Poland, at Chelmno, the initial Nazi mass murder and burial site, many of those asphyxiated were simply dumped and buried; records document almost 300,000 Jews and 5,000 Sinti and Roma lives were taken at or on-route to this location. In the early 1940s, three of the six sites of murder were built nearby rail-access. Belzec was established in March 1942 as part of Operation Reinhard and operated until December of that year. Cremation of bodies began in Belzec the spring of 1943 to cover up the traces of the mass-murders committed (Yad Vashem, 2022), consistent with Nazi policy goals to keep the “final solution” secret and to destroy evidence of mass crimes.

Sobibor was built behind a dense pine and birch forest in eastern Poland. It operated from April to July 1942, and again from October 1942 to October 1943, killing at least 167,000 people. Its small staff of about 40 people included Austrians along with some German soldiers, including people who had worked in the T–4, or “euthanasia,” program. “On October 14, 1943, the Jewish resistance in Sobibor launched an uprising, during which some 300 prisoners escaped. Most of the escapees were subsequently hunted… and killed, but some 50 survived the war” (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2022). According to Yad Vashem, prisoners who had been deported from their homes and from ghetto communities by train (in cattle cars) were told that they had arrived in a transit camp on the way to forced labor. Thereafter, people were sent to ‘showers’ for ‘disinfection’ and subsequently murdered with poison gas. Use of the term ‘showers’ in this context is only one of many examples of Nazi deception and imperial language designed to mislead both victims and the wider public (Klemperer & Brady, 2006).

Treblinka was also created in Operation Reinhard and was the site of murder of about 870,000 people from July 1942 to August 1943. It was designed to kill Jewish and other people in the General government area of occupied Poland. SS Commandant Franz Stangl managed this camp with assistance from less than 30 SS officers and less than 120 guards, mostly Ukrainian soldiers. Prisoners, as at other death camps, were hurried off trains, told they were at a transit point, promised showers and disinfection, robbed of all possessions, shorn, forced down narrowing paths that acted as chutes or ‘pipes,’ and then killed in gas chambers. Human corpses were then removed and buried by a select and soon-to-be-killed team of forced laborers, Sonderkommando.

Majdanek was, and its state museum and memorial site is, located on 667 acres near Lublin, Poland. The perimeter included an electrified double barbed-wire fence and 19 watchtowers. The camp included 22 prisoner barracks, 7 gas chambers, wooden gallows, a crematorium, and other buildings. Approximately 78,000 people were murdered at Majdanek, including approximately 60,000 Jewish people. Overall, about 150,000 people from 28 countries were incarcerated at Majdanek. Just before Soviet troops captured the site, Nazis tried to destroy it all, but they were not entirely successful (Yad Vashem, 2022).

Auschwitz was established in Oswiecim Poland in 1940 as a concentration camp for Poles. It was for a time slated to become a Soviet POW camp (Bauer & Keren, 2001). Technically a system of three distinct camps outside the town, it included the original concentration camp (Auschwitz I), the infamous site of the gas chambers and crematoria (Birkenau or Auschwitz II), and a forced labor camp (Auschwitz III, or Monowitz). Millions were infamously murdered therein, including Jewish people, other Polish people and Soviet prisoners of war, Roma people, and people of other nationalities (including Jewish Hungarians). Most were murdered, some died in other ways, and a smaller number survived and bore witness.

While operational as early as 1940, Auschwitz became an authorized and central site of industrial murder after the 1942 Wannsee conference. Efforts (including a resident music group or ‘orchestra’) were made to keep deprived and captive deportees from resisting at the entrance ramps. Auschwitz was the only camp that assigned and branded prisoners with numerical ink tattoos (for those selected for work). These identity numbers were used to facilitate daily roll call and to keep ‘order’ at all times, such as during the assignment and movement of people to forced labor.

In sharp contrast to false stereotypes that minimize the scope of Jewish armed resistance, Jewish uprisings or revolts took place in four of these six sites of murder (in addition to some ghettos). In some cases, uprisings by resistance groups damaged camp operations to the point where they became inoperable.

Goldhagen reconceptualizes the meaning of the death camps to highlight the clear intentions and widespread acceptance of these mass murder sites (Goldhagen, 1997). He suggests that long-standing and (by 1900) ubiquitous or “common sense” antisemitism in Germany evolved into a form he calls violent and eliminationist antisemitism. Killing factories were developed to eliminate an entire racialized population, among others, who were treated as natural enemies. Hatred, perhaps with a toxic combination of fear and envy (Aly & Chase, 2015), were used to rationalize the crime of genocide.

Conclusion

Nazi ghettos and camps were destructive tools of Hitler’s regime and the Nazi state. Jewish citizens of Germany and its annexed territories were, along with several other groups, subjected to persecution in actions that involved classification, deportation, segregation, dehumanization, extortion, robbery, forced labor, disease, overcrowding, spiritual and physical violence, and eventually mass murder. Nazis and their collaborators rationalized these crimes by appealing to fear and citing nationalist, expansionist, and racist goals. This evolved through six basic stages, starting with definition of targeted groups, and proceeding through dismissals and expropriations of businesses, concentration, exploitation of labor, annihilation, and confiscation of personal effects (Hilberg, 2003, p. 1065).

Human Rights formally established at the United Nations in 1948 recognize that we are all born free and with specific rights, regardless of our background. The UN also established and defined the crime of genocide to describe the horrific form of cultural destruction that is exemplified by the Holocaust. Generations since the Holocaust continue to work to educate us all and to prevent future injustices, including crimes of genocide. Member states of the UN continue to act as a global community committed to peace and security. After the Holocaust, many nations have increased our commitments to end crimes against humanity, to fight against prejudice, intolerance, and discrimination, and to include all individuals in the covenants that promote rights and responsibilities essential to the prosperity of our nations and our communities.

References

Aly, G., & Chase, J. S. (2015). Why the Germans? Why the Jews? Envy, race hatred, and the prehistory of the Holocaust.

Batalion, J. (2020). The light of days: The untold story of women resistance fighters in Hitler’s ghettos (First edition). William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Bauer, Y., & Keren, N. (2001). A History of the Holocaust (Rev. ed). Franklin Watts.

Berenbaum, M. (Ed.). (1997). Witness to the Holocaust (1st ed). HarperCollins Publishers.

Bergen, D. L. (2016). War and genocide: A concise history of the Holocaust (Third edition). Rowman & Littlefield.

Desbois, P. (2009). The Holocaust by bullets. Palgrave Macmillan, with the support of the United Stated Holocaust Memorial Museum. VLE Books

Duneier, M. (2016). Ghetto: The invention of a place, the history of an idea (First edition). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Dwork, D., Anger, P., & Jewish Foundation for the Righteous (Eds.). (2002). Voices & views: A history of the Holocaust. Jewish Foundation for the Righteous.

Dwork, D., & Pelt, R. J. van. (1996). Auschwitz: 1270 to the present (1. ed). Norton.

Dwork, D. & Van Pelt, Robert J. (2009). Flight from the Reich: Refugee Jews, 1933-1946 (1st ed). W.W. Norton.

Geve, T. (2021). The boy who drew Auschwitz. Open Athens

Geve, T., & Inglefield, C. (2021). The boy who drew Auschwitz: A powerful true story of hope and survival (First U.S. edition). Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Heberer, P. (2011). Children during the Holocaust. AltaMira Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Hilberg, R. (1985). The destruction of the European Jews (Rev. and definitive ed). Holmes and Meier.

Hilberg, R. (2003). The destruction of the European Jews (3rd ed). Yale University Press.

Kaplan, M. A. (1999). Between dignity and despair: Jewish life in Nazi Germany (First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback). Oxford University Press.

Klemperer, V., & Brady, M. (2006). The language of the Third Reich: LTI, Lingua Tertii Imperii: a philologist’s notebook. Continuum.

Knowles, A. K., & Jaskot, P. B. (2014). Mapping SS Concentration Camps. In Knowledge, Anne Kelly, T. Cole, & Giordano, Alberto, Geographies of the Holocaust. Indiana University Press.

Kuntz, D., & United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (Eds.). (2008). Deadly medicine: Creating the master race (3. printing). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Laqueur, W. (2001). The Holocaust encyclopedia. Yale university press.

Lengyel, O. (2000). Five chimneys: A woman survivor’s true story of Auschwitz (Reprint. der Ausg. 1995). Academy Chicago Publ.

Lorant, S. (1935). I was Hitler’s prisoner: A diary. G. P. Putnam’s sons.

Megargee, G. P. (2020). Tools of the State: The Universe of Nazi Camps. In L. J. Hilton & A. J. Patt (Eds.), Understanding and teaching the Holocaust (pp. 95–107). The University of Wisconsin Press.

Ofer, D., & Weitzman, L. J. (1998). Women in the Holocaust. Yale university press.

Orth, K. (2010). Camps. In The Oxford Handbook of Holocaust Studies (pp. 364–377). Oxford University Press. Oxford Academic

Stone, D. (2017). Concentration camps: A short history. Oxford University Press.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). (2022). Holocaust Encyclopedia. USHMM Holocaust Encyclopedia

Wachsmann, N. (2015). KL: A history of the Nazi concentration camps (First edition). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Westermann, E. B. (2021). Drunk on genocide: Alcohol and mass murder in Nazi Germany. Cornell University Press.

Whitman, J. Q. (2017). Hitler’s American model: The United States and the making of Nazi race law. Princeton University Press.

Yad Vashem. (2022, June). The Holocaust. The Death Camps. Yad Vashem

Yahil, L. (1991). The Holocaust: The fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945 (I. Friedman & H. Galai, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

To take somebody’s property and use it without permission. OED 2022

To be treated in a cruel and unfair way, especially because of race, religion, or political beliefs. OED 2022

To work to make a person lose their human qualities such as kindness, pity, etc.; to make people seem like objects rather than human beings. OED 2022

An isolated, circumscribed site with fixed structures designed to incarcerate civilians. Stone, 2017