Enablers

The Arts and Nazism: Aesthetic Adventure and Political Terror

Marion Kant

Part I: The Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda and the Reich Culture Chamber

On March 13, 1933, only a few weeks after the Nazi ascent to power, a new ministry was founded by decree: the Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda, “Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda”. Dr. Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945 suicide) was put in charge as Reich Minister. The Ministry attempted to take total control over every feature of culture and the arts; all aspects of artistic production, distribution, and communication now fell under ministerial influence, supervision, and inspection. Art was to proclaim, convince and celebrate – to propagate in the widest sense – the revolutionary changes that were sweeping across Germany and “to place the nation firmly behind the idea of the National Revolution” (Goebbels 1933a). It was to secure the hegemony of Nazi ideology and instigate an intellectual and spiritual mobilization throughout Germany (Goebbels, 1933b), it was to “make propaganda for our own honest convictions.” The Ministry was meant to advertise for the Nazi ideal, and to “fight using all good means to make good propaganda to win the soul of our people.” (Fritzsche,1934, 330f) Propaganda became “the neglected weapon of German politics … a creative art.” (Fritzsche,1934, 330)

The Ministry took its seat in the government quarter in Berlin, in the Ordenspalais, “Palace of the Order”, an 18th century building on the Wilhelmstrasse “Wiliam Street”, opposite the Reichskanzlei “Reich Chancellery” where Adolf Hitler (1889-1945 suicide) had his office. Replications of the ministerial structure were put in place in every Reichsgau or “regional administrative unit in the Third Reich”, in every region of the Third Reich, with miniature administrative entities throughout the country. That amounted to a tight and formidable net of institutional authority, erected at rapid speed.

Every political system is based on some kind of ideological orientation that makes it possible to turn ideas into practice; every political system establishes a legal framework that enables and protects the realization of such philosophies and ideologies.

Nazism represented the continuation of conservative and folkish movements of the 19th century. Like its predecessors, it cultivated particular aesthetic approaches, and sustained those approaches that stressed German and Germanic cultural values. The Third Reich “Empire” broke with the democratic and broadly social democratic attitudes that governed the Weimar Republic. But it continued massive support of many art forms and continued with the assumption that the arts were a vital part of the construction of a national identity.

The newly founded Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda was the most important bureaucratic structure to further Nazi ideology, to enable the creation of a Nazi aesthetic and secure the Nazification of the arts. It centralized federal institutions and henceforth attempted to exert total control over all intellectual life in the Third Reich. This was a huge, ambitious, and unheard-of task. The Ministry started with five departments and 350 employees. But the mission was so immense that its structure grew steadily. By 1939 it had three state secretaries and 17 departments that observed all intellectual activities that were happening throughout the German Reich.

State Secretaries, or deputy ministers, were responsible for different aspects and portfolios of the Ministry’s work. The position of State Secretary I oversaw the German press, the foreign press, and newspapers in general. Economist Walther Funk (1933–1937) was installed as State Secretary I, followed by political scientist Otto Dietrich (1937–1945). The role of State Secretary II was a particularly large portfolio, responsible for the budget, law, propaganda, radio, film, staff matters, defence, international matters, theatre, music, literature, and visual arts. This position was filled by Karl Hanke (1937–1940), a milling engineer, followed by Leopold Gutterer (1940–1944), who had studied German philology, theatre studies and ethnology. Werner Naumann (1944-1945), a political economist, served very briefly at the end of the Third Reich. As State Secretary III, the journalist Hermann Esser (1939–1945) served in the least important role that oversaw tourism in the German Reich.

How can anyone, let alone a bureaucratic structure, exercise such total control over artists and their works? This control worked in several ways.

The Ministry, like a huge censorship office, established rules that provided guidelines for what was allowed and what was forbidden. But it wanted much more than censorship; it wanted to be the force that stimulated artistic creation. It attracted artists with their works of art and asked them to integrate into its structure, and at the same time, it barred and persecuted those who did not fit into its ideological frame. It administered financial means to support preferred works of art; it spent substantial sums of money on the arts throughout the existence of the Third Reich. The ministry could exert control through its structural set-up on a theoretical as well as practical level; it could advise how to enable the creation of works and it could outline the aesthetic orientation that it wanted artists to follow. Some artists were easily enticed by the advantageous working conditions that the Ministry offered; others were coerced by pressure put on them to engage with the artistic propaganda effort.

The Propaganda Ministry understood itself as the “spiritual center of power that stays in constant touch with the whole people on political, spiritual, cultural, and economic matters. It is the mouth and ear of the Reich government.” (Fritzsche 1934, 330-342) For this reason, to spread the message and enable artistic propaganda country-wide, another administrative structure was created, that of the Reichskulturkammer “Reich Culture Chamber”.

Goebbels explained its role: “It is a fundamental mistake to think that the task of the Reich Chamber of Culture is to produce art. It cannot, it will not, and it may not. Its task is to bring culture-creating people together, to organize them, to remove the restrictions and contradictions that surface and to assist in administering existing art, the art being produced today, and the art that will be produced in the future for the benefit of the German people.” (Fritzsche, 1934, 330-342)

The Reich Culture Chamber acted as a subsidiary force of the Propaganda Ministry. With its seven sub-chambers, each dedicated to one of the arts – literature, music, fine arts, theater, film, print media, radio – it held a tight grip on all aspects of culture and art. It did precisely what Goebbels had outlined: it assisted in creating conditions that encouraged art, old and new, to be produced and reproduced.

Mirror images of the chambers were also erected throughout the Reich, just like the Ministry replicated its structure, so did the Reich Culture Chamber; this cultural administration covered the whole country like a spider’s web. Membership in one of the chambers was obligatory for those pursuing professional artistic careers. Proof of Aryan ancestry (fulfilling the “Aryan Paragraph”) was the precondition for applying and being granted membership. Here, in the acceptance of and submission to the application criteria lay the ultimate complicity with the racial politics of the Nazi regime. It is shocking to look at the members’ lists and consider how high this complicity of artists was. In this act of membership lay the first step to assist the regime and it is with this act that artists can and have to be held responsible for their involvement in the regime.

The chambers were led by artists as well as lawyers or party functionaries; the artists sometimes were members of the Nationalsozialistische Arbeiterpartei (NSdAP or Nazi) “National Socialist Workers Party” but often they were not. In other words, party membership did not determine artistic success or failure in the Third Reich. Yet we cannot make a distinction between Nazis on the one hand controlling and enforcing an aesthetic, and “artists” on the other, forced and condemned to follow such a prescribed aesthetic.

After March 1933, all the arts were realized and coordinated within this new, powerful, centralized administration in which artists were active participants and administrators in similar structures to other Nazi offices. The creation of new organizations and institutions was to make total Reich regulation possible through voluntary efforts and direct involvement of the artists.

Nazi vocabulary and Nazi legal codes might not have been set up by artists, but artists accepted and exploited them. Artists sat in the administrative offices of the Propaganda Ministry or the Reich Culture Chamber, directed the educational authorities, and assisted the propaganda units in the Reichsgaue. The racial Nazi ideology as the guiding principle for the making of any art became a reality throughout Germany, both in theory and in practice; artists knew and approved of the fact that they were becoming the ‘ideologues’ and the ‘propagandists’ of the Third Reich. They took the power offered to them and they used it.

The Nazi Aesthetic

An aesthetic philosophy can only develop if an ideology is strong enough to carry and define it. Whether a Nazi ideology existed is as contested as the associated question that concerns the existence of a Nazi aesthetic. (See Mosse 1964) If it is assumed that such a coherent ideology did not exist, an associated aesthetic can also not have emerged. In that case, independent ideological strands would loosely outline equally independent artistic practices.

But we suggest the opposite: that we can speak of a Nazi ideology that was coherent, powerful and convincing; as a result, we can speak of a Nazi aesthetic which followed the fundamental ideological orientation of the Nazi state. If a Nazi aesthetic existed, how could it be defined and what would characterize it? How are politics translated into aesthetics, and how do aesthetics conceptualize and drive politics? Aesthetics established as well as fulfilled the ideological framework of the Third Reich in a dialectical and dynamic relationship in the following ways:

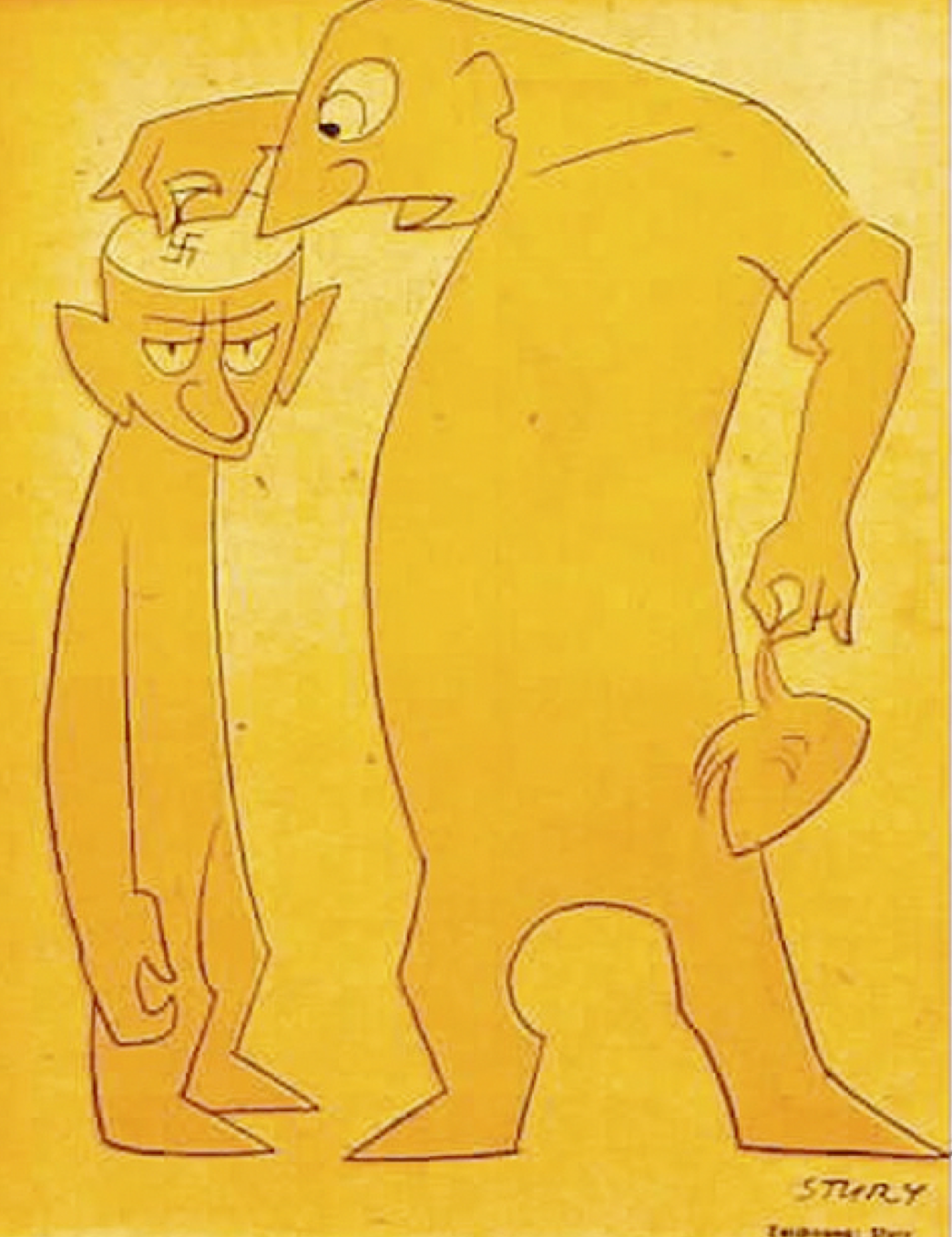

- Aesthetics reinforced propaganda and beliefs of a superior “Aryan race” and an inferior Jewish race; Jews produced entartete Kunst “degenerate art” because they belonged to a “degenerate” race.

- Another category of this racial view was the classification of Slavs, Russians, Poles, Ukrainians, White Russians as ‘untermenschen’ “subhuman”, along with the identification of Jews as Marxist and Marxism/Bolshevism as Jewish.

- The “degeneracy” of race extended further to Sinti and Roma, to the mentally unstable and physically disabled, to Afro-Germans or Africans, and this mattered in the context of music and primitivism in art.

- Aesthetics reinforced the leadership principle, embodied in Adolf Hitler as Führer, “Leader”. The leader became “a social product” as Ian Kershaw suggests, and a whole state machinery had to work towards the Führer: “The legacy of Hitler belongs to all of us. Part of that legacy is the continuing duty to seek understanding of how Hitler was possible … the character of his power derived only in part from Hitler himself. In greater measure, it was a social product – a creation of social expectations and motivations vested in Hitler by his followers.” (Kershaw 1998, xiv, xxvi).

- The Volksgemeinschaft “People’s Community” was represented as the embodiment of the racially, ethnically, and culturally homogenous community.

- This imagined community required an ever-expanding Lebensraum “living space” to fulfill its destiny, to conquer and rule the world.

- There was the need for culture and the arts to articulate, propagate and activate the essences of the race and community, to infuse the Lebensraum with meaning and values.

These were the main political-ideological categories that stood in relation to — and needed to be transformed into — art. Vice versa, art and artists tested the viability of political concepts and now helped to articulate them in a new social and political context. The Third Reich established an aesthetic reference framework that was inseparably connected to its racial ideology and thus art also became part of the Nazi racial state.

The control exerted over all arts through the various cultural institutions – a control carried out by artists, not anonymous Nazi bureaucrats – guaranteed that artists adhered to the announced framework. In most cases this was voluntary. Artists acknowledged and worked in accordance with this framework – either because they had already discovered and promoted racially driven ideas — or because they were willing to integrate them into their works after the Nazi ascent to power.

That does not mean that all art was the same; this Nazi aesthetic framework was complex, multi-dimensional, and sophisticated. It valued and incorporated important historical trajectories yet also created new formal points of orientation. There was only one acceptable ideology that of the Nazis. But the creation of art did not become impossible.

Interpretation was possible, even necessary, and that makes the assessment of art created under the Nazi regime so difficult today. Creativity was possible not least because the ideas that flowed into the Nazi ideology encompassed many artistic traditions that evolved during the late 18th and the 19th century. These were then synthesized into a folkish, nationalist way of thinking. These were not insignificant movements. They had explored German identity through concepts such as patriotism, nationhood and citizenship, heroism, religiosity, and belief, sacrifice and transcendence, notions of a unified country and who did or did not belong to the nation (this aspect specifically discussed the status of the Jews). We can trace these concepts in the works of romantic philosophers and writers, painters and composers. The traditions on which the Nazis built the aesthetic canon were rich, but often also contradictory.

The aesthetic framework that the Nazi regime assembled mainly followed along conservative interpretations of the classical and romantic traditions of German literature and the arts, of German culture in general. This canon contained the works that had provided a German national identity in the past and that remained especially important as a guide towards the making of new works of art. It was juxtaposed by the “negative aesthetics” of art that was deemed “degenerate”.

Of particular importance were Richard Wagner’s (1813-1883) aesthetics. His operas and his theories, above all the concept of a Gesamtkunstwerk, the “total work of art”, that enabled a people to bring together all arts in a new unity and that circumscribed a communal, national, German cultural consciousness, were declared a perfect embodiment of the approach to the creation of art. Wagner’s operas displayed all the qualities that German art should have. It is therefore no coincidence that Hitler’s musical preferences lay with the Wagnerian works. This preference went far beyond personal taste. If Hitler was the product of social forces, as Ian Kershaw suggests, if he represented the “Will of the German people,” then his aesthetic choices represented the expression of “German aesthetics” and his particular interest in Wagner’s writings and works demarcated national “German” music and “German” art.

There was no interruption of the “German” performance repertoire in theaters or opera houses, nor were “German” museums destroyed – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), Heinrich von Kleist (1777 – 1811), Gerhart Hauptmann (1862-1946), above all William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), inspired the dramatic repertoire; Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), Richard Wagner as case of German perfection, as mentioned, Robert Schumann (1810-1856), Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), Max Reger (1873-1916), Hans Pfitzner (1869-1949), Richard Strauss (1864-1949) defined the concert programs; Caspar David Friedrich, Adolph von Menzel (1815-1905) or Ludwig Richter (who illustrated the brothers Grimm’s “Children and Household Fairy Tales” were exhibited and upheld as aesthetic prototypes. Yet, at the same time, anything labelled “Jewish” was banned and any “Jewish” influences were discontinued.

In addition to the nurture of the traditional values, there was an attempt to create and support modern and contemporary works of art, in music, theater, literature, the fine arts, and particularly in film. They too were broadly defined by rediscovering the classical and romantic traditions. Works were to be invented that furthered the ethics of Nazi society and embraced the Nazi view of history. This modern, contemporary art was to accept tradition as guiding example and was to model itself on established aesthetic criteria yet, at the same time, present a contemporary and modern society. The processes of “re-orientation towards Nazism” and the cleansing “degenerate art” from the German canon through “Aryanization” were just the overt manifestations of finding new definitions and a new meaning for the new, Nazi society.

To grasp the existence of a Nazi aesthetic, it is vital to understand the ideological framework with its racial logic. The Nazi cultural administration had strong views on aesthetic conceptions and on many aesthetic practices. But the framework was never so strict that the creation of art became impossible. The interpretative space was large and flexible enough to accommodate many different forms of exploration and many styles and modes. It is a serious misunderstanding to think that the Third Reich was without art, even without its own modern art. The barbarism of the regime lay in the paradox of the German nation: a rich cultural heritage that it treasured and cultivated along with the destructive and murderous politics that it advanced in the name of its culture.

The Importance of the Arts in Germany

The arts had been a vital factor in establishing a national German identity; the Nazis, with their focus on propaganda as the art of ideological indoctrination, needed them ever more. No political pamphlet could achieve what literature, music or theater could. One of the most influential positions in the Propaganda Ministry, following closely after Goebbels as minister, was that of the Reichsdramaturg “Reich Dramaturg”. This position was occupied by Rainer Schlösser (1899-1945, convicted by a Soviet army tribunal of war crimes and executed). He was, like Goebbels, a university educated man with a PhD. Goebbels had been awarded a doctorate in philology for writing on the romantic German playwright Wilhelm von Schütz. Schlösser earned his doctorate on the analysis of depictions of the historical figure Johann Friedrich Struensee in German literature.

The term “dramaturge” was used by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781) in his work Hamburgische Dramaturgie (1767), to denote someone who constructs conceptual dreams and designs programs for the national theater. The creation of the position of Reichsdramaturg, therefore, points to the strong sense of historical obligation that the Nazis felt and wanted to demonstrate to the German population. It points to the deliberate continuation of traditions and their renewed contemporary application and gives a concrete example of how historical knowledge was applied in 1933 and 1934. The Nazi narrative, drawn from a careful selection of historical events, was about struggle, racial oppression, sacrifice, and victory. The past provided material for the myth of German supremacy. The arts were utilized by the Nazi administration to make this supremacy visible, audible, comprehensible – to make the arts the embodiment of a German conscience, of national-socialist values and visions. The Reichsdramaturg envisioned, orchestrated, and enabled the making of Nazi art, always following the ministerial mode of Goebbels’ precedent.

The arts became national institutions – a national literature, a national theater, a national music – and contributed to the making of the German nation in a major way. Romanticism in the early 19th century drove this process and projected a unified Germany when such a country and nation did not yet exist as a political entity. Politics, in this and many other instances, followed the arts and their utopian projections. The arts set the political agenda rather than only responding or reacting to social changes. Germany was known as the Kulturnation, the “nation of culture”. Culture was the basic tenet on which the idealized nation – Germany – rested.

In the Nazi view of history and politics, no other state and nation placed so much value on the arts and on culture; their admiration and protection of the arts placed them in the long line of rightful heirs of a great past. The Nazis acknowledged and exploited that heritage to legitimize their own racial politics.

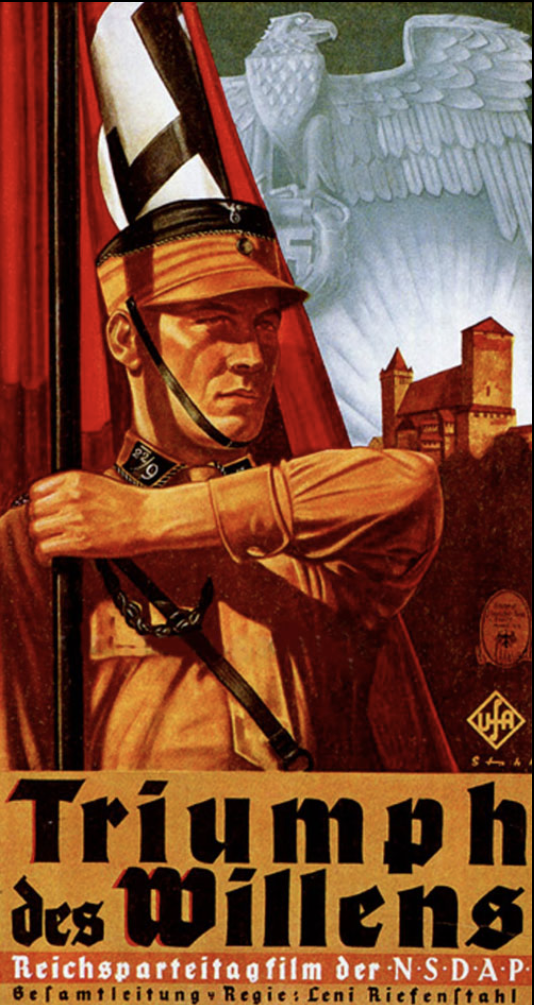

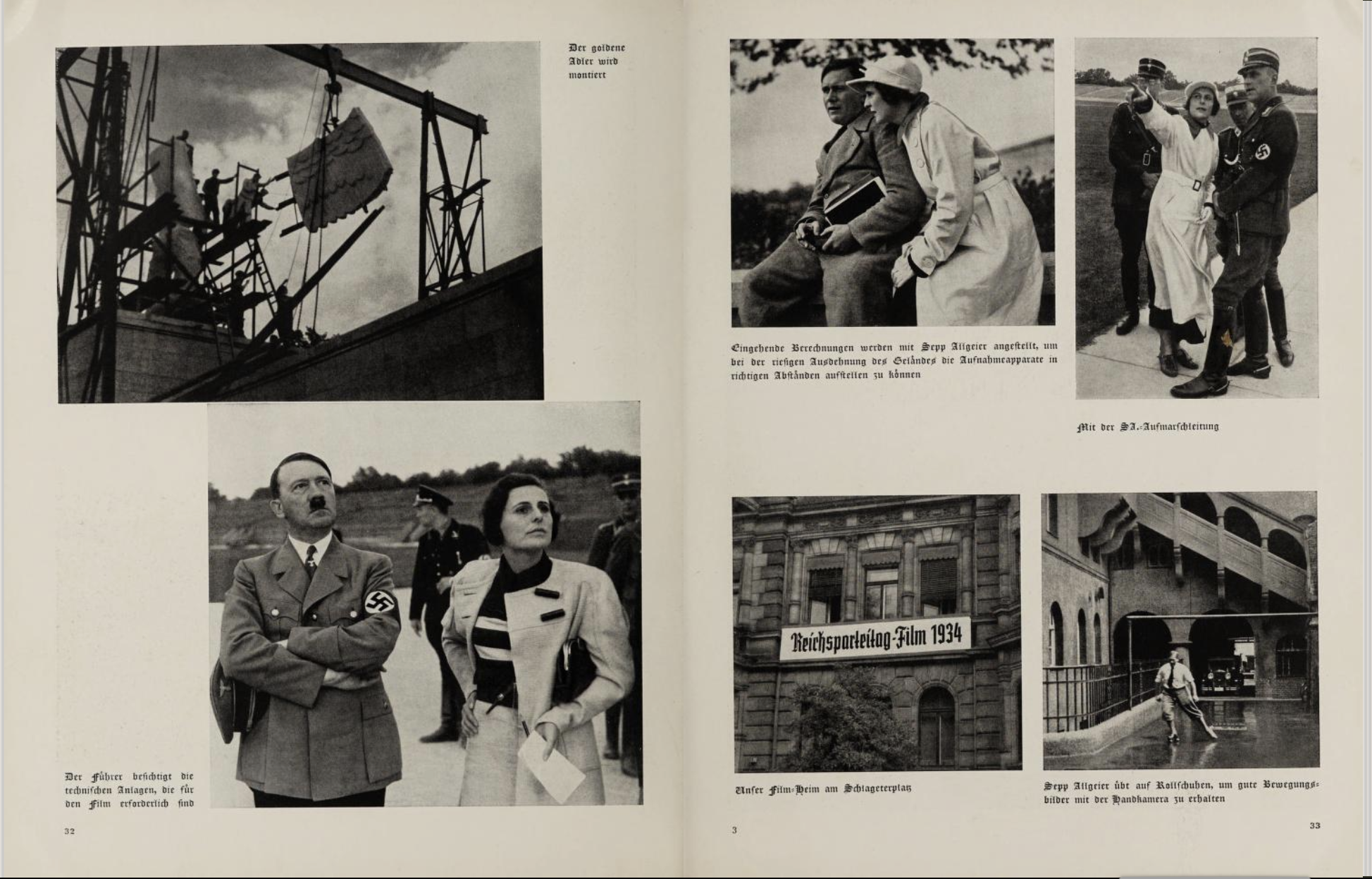

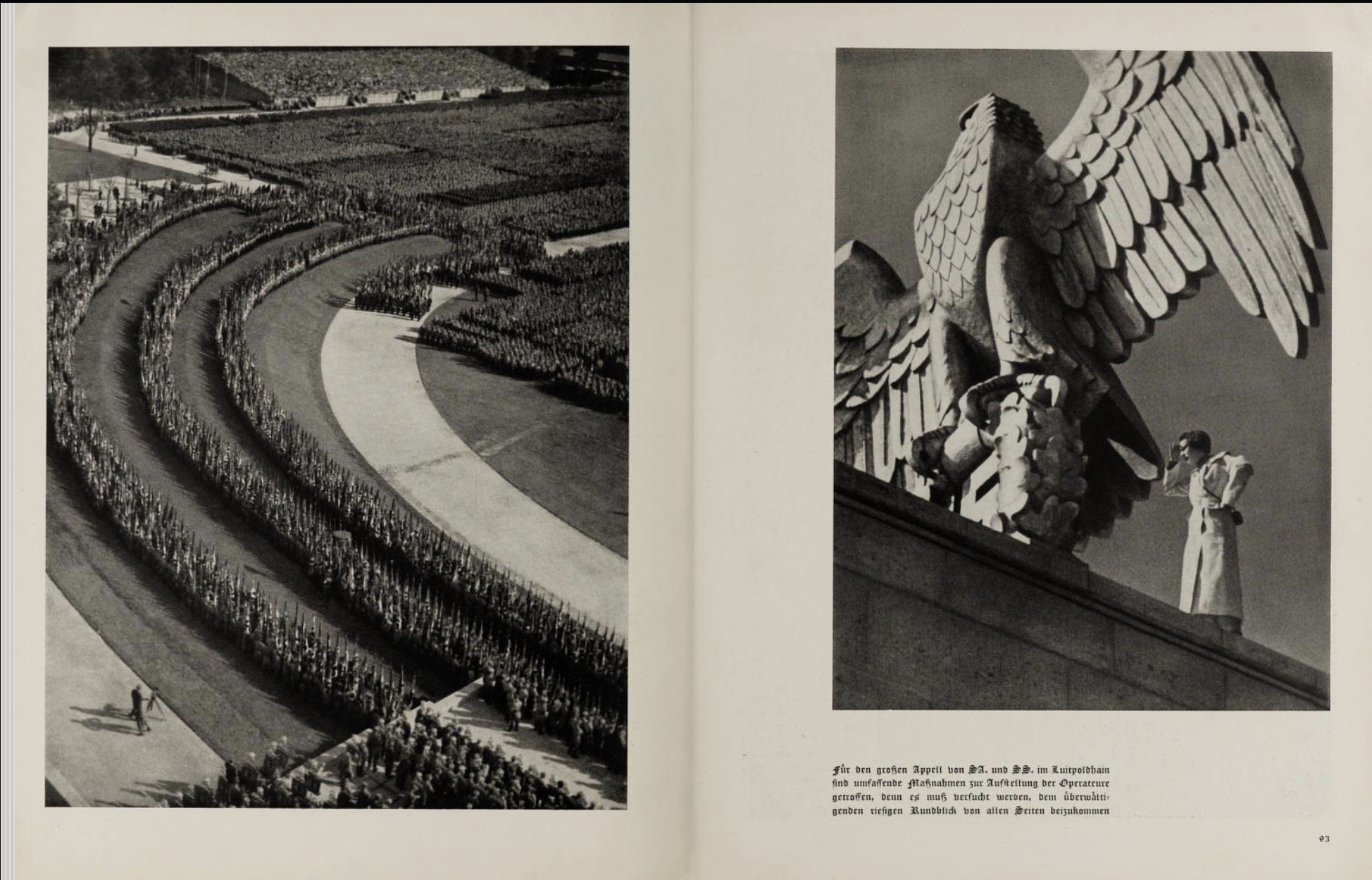

Several scenes in Leni Riefenstahl’s (1902-2003) films demonstrate how this perspective was translated into images. In Triumph of the Will, the film on the 1934 Party Congress of the NSdAP, the town of Nuremberg is framed as medieval incarnation of the previous glorious German centuries. It is also the town of Richard Wagner’s opera The Master Singers of Nuremberg (1867). Hitler, the savior of Germany, descends from the heavens to bring the message of hope to the jubilant Germans who line the picturesque streets to greet him, follow him, and turn his message into action. The historical trajectory creates a route from a desired past, the Middle Ages, to the present that is so full of promise. It conveniently eliminates ‘unwanted’ pasts, the recent years of the Weimar Republic, for instance, in a few statements and images.

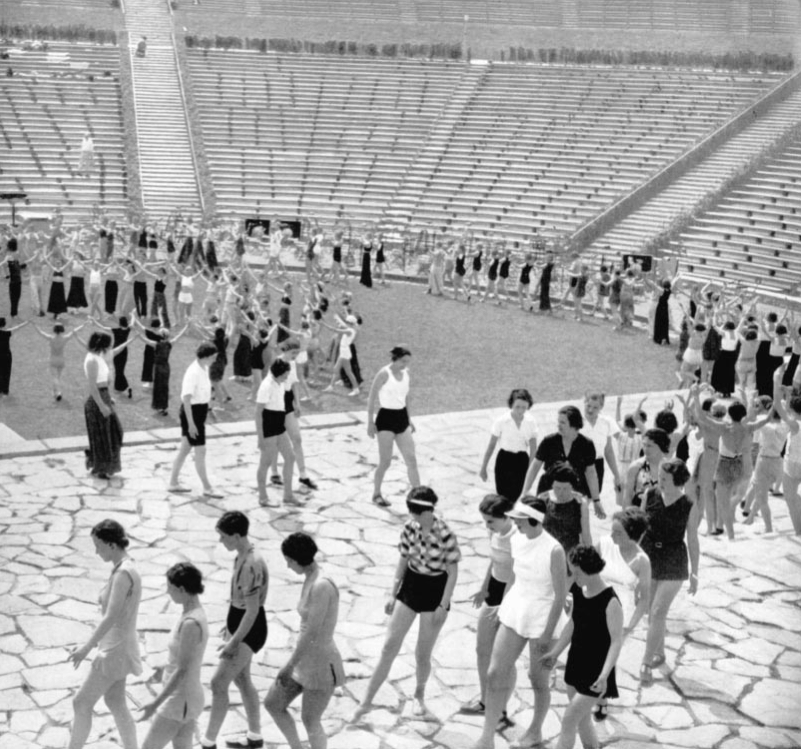

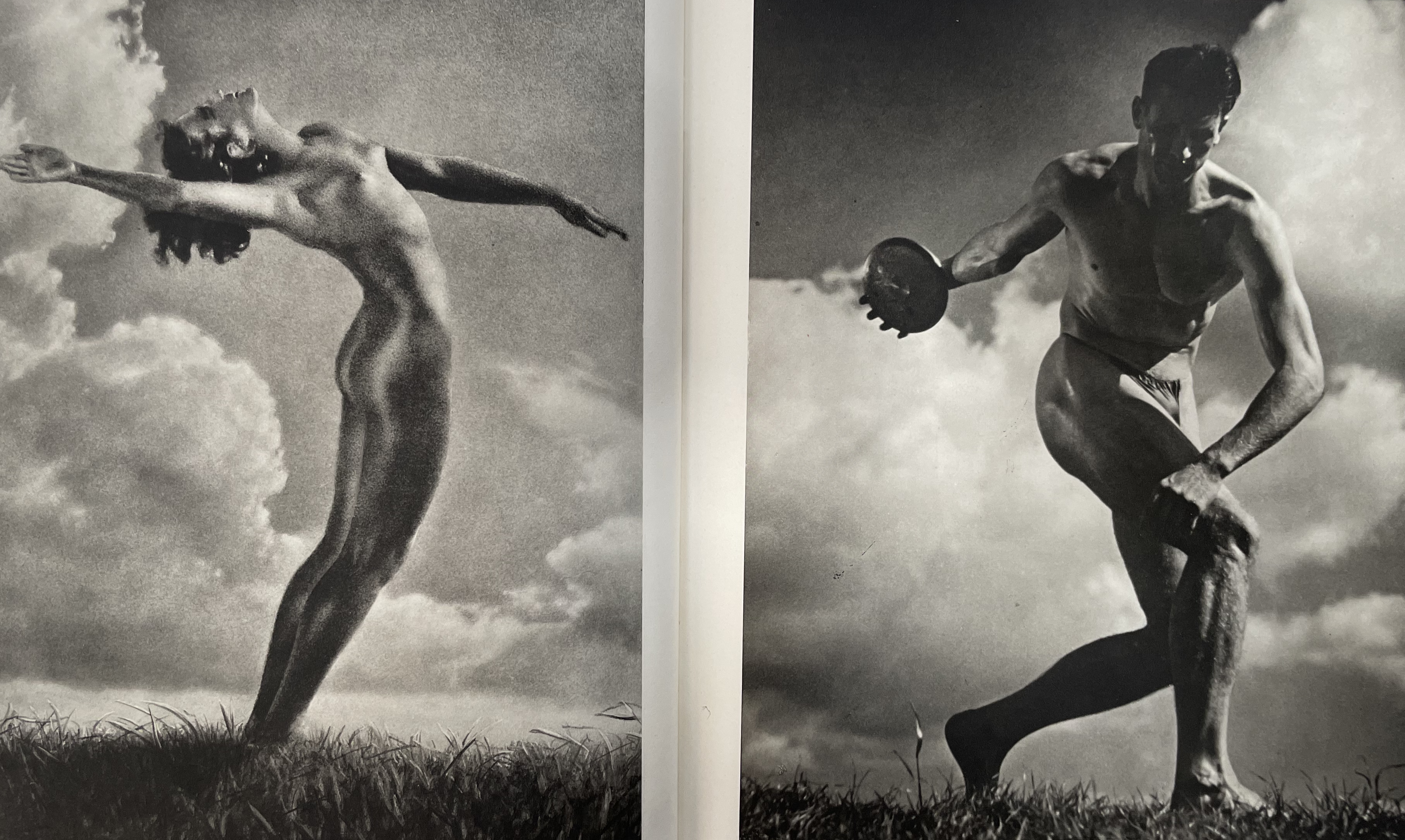

The introduction to Olympia, Festival of the Nations (1938), a film about the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, takes the viewer back to the ruins of Greek antiquity. It traces the birth of the games from the Acropolis to the newly built, modern sports stadium in Berlin. Through historical space and historical time Greece as cradle of Western civilization is transposed to contemporary Germany. Germany, it is implied, is the genuine heir of this ancient civilization, of its beauty, health and strength. The ancient Greek athletes, literally, move into the bodies of German men and women and infuse them with the rhythms of life. The spirit of Myron’s sculpture (460-450 BC) is taken by the torch bearer through the elements of fire, water and wind to the discus and spear throwers competing in 1936.

The inherent barbarism of this Kulturnation – the claim of the greatness of the past created by culture, was already recognized by Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) who wrote: “There is never a document of civilization [Kultur] that is not at the same time one of barbarism. And just as such document is not free of barbarism neither is the process of transmission by which it is transferred from one owner to another.” (Benjamin, 1974, 253f). This barbarism is symbolized by Riefenstahl’s appropriation of ancient Greece, or the concentration camp Buchenwald and its geographical and ideological closeness to the town of Weimar, the center of German classical and national literature, the home of Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller.

As much as the Nazis, and the Propaganda Ministry in particular, furthered the arts and cherished them, they made clear distinctions between the traditions they considered valuable, and those they deemed “degenerate” and hence dangerous and destructive. The preferences of the Nazis were imposed as racial categories on aesthetics: “degenerate races” produced “degenerate art”; they had to be spiritually, intellectually, and physically destroyed. “Culturally he [the Jew] contaminates art, literature, the theater, mocks the natural sensibilities, overthrows all concepts of beauty and of the sublime, of the noble and the good, and instead drags men down into the sphere of his own base nature.” (Hitler, 1943, 358)

Nevertheless, this racial ideology, though imposed consistently from 1933 onwards, never managed to identify general “Jewish” traits in any of the arts. Rather, Judaism in the arts was defined through the specific characteristic of the oeuvre of individual artists. Jews were accused of picking the wrong subjects, distorting German reality and being incapable of understanding the beauty of the German People’s Community. Jews, according to Nazi ideology, contaminated everything that came into contact with them.

Thus, artists and their works were classified as Jewish: Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), who developed the theory and practice of Epic Theater; Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951) who developed the principle of composing with twelve tones; Emil Nolde, an influential expressionist painter who was deemed “degenerate.” But only Arnold Schönberg was Jewish and even he had converted to Protestantism in 1898. He reconverted back to Judaism in 1933 in protest of the Nazi ascent to power. Bertolt Brecht had no Jewish family background, but he was a committed left winger with communist sympathies and that by affiliation made him “Jewish.” The Nazis consistently identified Marxism as Jewish and Judaism as Marxist. Nolde, on the other hand, was a dedicated national socialist and begged Goebbels to accept his modernist stance yet was banned from “German” exhibitions. Instead, his works were placed in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition of 1937. In these few examples we see not so much the randomness of aesthetic decisions but rather the logic that anything that departed from the classic and romantic conservatism that the Nazis favored had to be condemned and excluded. It could then easily be labelled “Jewish,” either because of its modernist associations or for its left-wing political affiliations.

![The title “Kunst” [art] is placed in quotation marks thereby questioning the ethical and aesthetic validity of the exhibited works. The sculpture Large Head by Jewish artist Otto Freundlich (1878-1943) was to represent everything wrong with modernist art.](https://psu.pb.unizin.org/app/uploads/sites/229/2022/09/image9.png)

Though the assessment of “Jewish degeneracy” commenced on a personal and individual basis, with the long and constantly updated blacklists distributed across the country, there were artistic movements and institutions that were accused of “degeneracy.” The Bauhaus (see James-Chakraborty 2006) was one such institution that above all others was considered “Jewish.” It had been founded in Weimar in 1919 and represented the ideals and norms of the Weimar Republic. The connection between Judaism and Marxism led to the closing of the institution in 1933. Few members of the Bauhaus were Marxists and even fewer were Jewish. But the Bauhaus, with its founder Walter Gropius (1883-1969), advocated the social-democratic standards of the Weimar Republic. It envisaged a socially just society, promoted equal opportunities in education and believed in radical social change through aesthetics.

The Bauhaus members believed in the power of the arts and their revolutionary and transformative impact; they taught their artistic programs in this spirit and in the conviction that the arts were able to influence and could change the social environment. When the Bauhaus was closed in 1933, several masters and teachers emigrated after the Nazis began persecuting them: Walter Gropius taught at Harvard University, Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) taught at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Vasily Kandinsky (1866-1944) settled in Paris, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) one of the few Jewish artists, emigrated to the UK and in 1937 to Chicago. The majority of teachers and students, however, remained in Germany and accommodated Nazi demands.

In the next chapter we shall see how Nazism grew its own modernist arts even though it rejected much of the earlier 20th century modernist movements outright. We shall examine how “art and politics were but two sides of the same, racially minted coin.” (Spotts 2003).

Part II: Art as a Weapon: Aesthetic Strategies for the Third Reich

Nazism grew its own modernist art even though it rejected many of the earlier twentieth century modernist movements outright.

Who were the artists who supported the Third Reich? Is Peter Adam correct when he states that: “One can only look at the art of the Third Reich through the lens of Auschwitz”? (Adam, 1992, 12) and: “One cannot stress enough the fact that everybody who built, painted, wrote for the regime, who approved of or encouraged the National Socialist art world, supported at the same time the political system which ruled over it…” (Adam, 1992, 19)

Were these artists – writers, painters, sculptors, architects, filmmakers, dancers, actors and designers – insignificant, poorly educated, ignorant, incompetent people or merely opportunists who were forced into decisions they never chose? They might have been selfish, they might have been ignorant and refused to consciously acknowledge the politics of the regime, but that does not relieve them from taking responsibility for the murderous consequences of Nazi ideology. Nor does it relieve us today from accepting that the Third Reich convinced great and important artists to collaborate with its regime. The arts were the other side of the political coin (Spotts 2003) and we must not make the mistake of underestimating the importance that the arts played, nor of separating art from the politics of the Nazi regime.

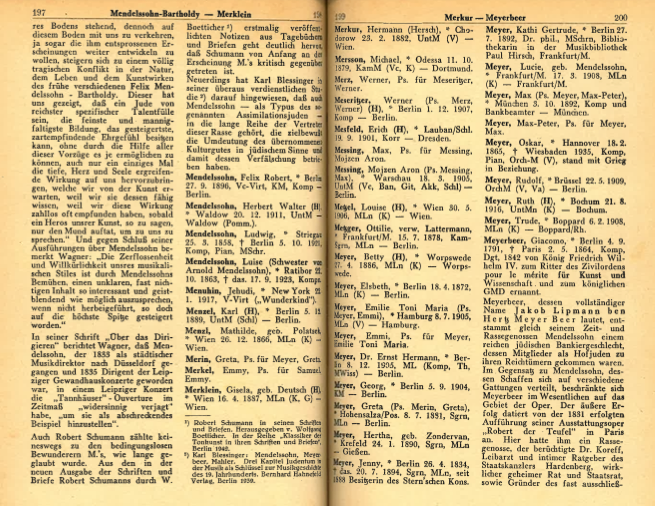

All artists in the Third Reich operated within the racial juxtaposition of German art versus “degenerate” art. They accepted this division when they became members of one of the Reich Culture Chambers. Once they accepted it, and once they had allowed the Nazi takeover of institutions and organizations, the possibilities to protest and resist became fewer. They did not prevent the book burnings in 1933, they did not oppose the lists of banned people and works – of “Jewish” descent and thus “degenerate” – that the Propaganda Ministry and the Reich Culture Chamber regularly published. The exhibitions on “degenerate” art in 1937 (see Barron, 1991) and on “degenerate” music in 1938 (see Dümling, 1988, 1989) were two overt examples of the attempt of racially purging intellectual life. Both exhibitions were complemented by shows with “German” art and music to demonstrate the power of an unpolluted art. Few artists dissented.

Hitler, in a speech delivered at the NSdAP Party Congress in 1935, outlined what German art should contain: “We shall discover and encourage the artists who are able to impress upon the State of the German people the cultural stamp of the Germanic race . . . in their origin and in the picture which they present they are the expressions of the soul and the ideals of the community.” (Hitler, in Adam, 1992, 15-16) That was a programmatic announcement that provided the general direction, without prescribing a specific aesthetic rendition, toward which artists should work. “Race,” the soul and fate of the German people, the Volksgemeinschaft, the “People’s Community”, led by the Führer Adolf Hitler, provided the main categories that needed to be worked through in art. The Nazis aspired to this ideal community of a racially purified social order, in which “degenerate” elements – Jews, Sinti, Roma, Africans, Bolsheviks, Marxists, etc. – had been eliminated. These categories belong to the index of Nazi ideology, and we are now going to examine how they made their way into aesthetic production and what kind of strategies artists devised to deal with the demand to create a German art.

The main cultural strategies of the Nazis addressed, 1st, the continuation of the artistic traditions, the theatrical and musical repertoire, for instance, 2nd, the creation of new works, for instance the invention of a new performance genre, the Thingspiel “Thing Play” 3rd, the integration of modernist, occult, folkish defined aesthetics, for instance in literature and dance and 4th, the constant counterpoint of trying to define and then eradicate “Jewish” aesthetic tendencies and techniques.

The Policy of Coordination, or “Gleichschaltung”, of the Theater

After 1933, the theatrical traditions of the past centuries were upheld with excellent directors and excellent actors who remained in the Third Reich. They shaped and at the same time took ‘opportunistic’ advantage of the new possibilities. High subsidies for theater productions and advantageous contracts for performers secured the uninterrupted continuation of the repertoire.

Many scholars agree that the “demands placed by the national-socialist regime and its leaders on dramatists and performers were total. Only unconditional surrender was possible, complete conformity, complete withdrawal from public life or emigration. Alfred Rosenberg (1893-1946 execution by hanging), who had contributed to the evolution of a national-socialist ideology in his book Myth of the 20th Century spoke of a ‘unified will’ that intricately wove together ideology and art from the first awakening of the racial soul…” (Simhandl,1996, 252)

That statement is both correct as well as misleading: many artists defined as “Jewish” or “left-wing” emigrated if they had the means and opportunity to do so; some (albeit few) German artists withdrew from public life. Most were happy to conform, either because they agreed or were focused on their career and no price was too high to pay for success. But we must remember that theater, ballet, opera, the concert scene and the film industry thrived with dedicated support, as did artists who did not mind being co-opted into the Nazi cultural administrative system. They did not merely surrender; they adapted to and adopted the new demands of the system; some artists had helped to create these demands in the pre-Nazi years and decades. They supplied the regime with the art it needed and desired. They substantiated the ideological and political programs of the national socialists.

Radical, innovative, and experimental directors such as Gustav Gründgens (1899-1963), Karl-Heinz Martin (1886-1948), Jürgen Fehling (1885-1968) or Lothar Müthel (1896-1964) did not simply surrender. Gustav Gründgens occupied one of the most powerful theater positions as Generalintendant der Preußischen Staatstheater “General Intendant of the Prussian State Theaters” after Jewish director Leopold Jessner (1878-1945) was ousted, exiled, and fled to the United States. Gründgens staged masterly crafted productions and performed in them. His Faust interpretation is admired even today. He produced Shakespeare’s Hamlet as a “Nordic saga” in which the Germanic thinker comes into conflict with powers destroying his race.

This betrayal of every moral principle for the sake of power and career was portrayed in Klaus Mann’s novel Mephisto (published in 1936). The novel, (and the film after the book by István Szabó, 1981), traces the Nazification of the theater and shows how a gifted director and performer like Gustav Gründgens was drawn towards Nazi collaboration and treachery, how he was caught in the net of lies, concessions and deceit; once caught, he could not escape.

“Can the cultural losses which Germany suffered after 1933 at the hands of the N.S. [National Socialist] dictatorship be measured? The number of those emigrants who belonged to the ‘cultural’ emigration is not exactly determinable…” (Strauss et all, 1999, L) About half a million German speakers emigrated; that represents one tenth of the entire European exile movement. (Krohn 1998, 449) Most left because they had been classified as “Jewish”; but about 30,000 exiles were also active opponents of the regime. Many of them belonged to the artistic intelligentsia. (Strauss et all 1999, XIII) We can assume that the emigration in all art forms amounted to 5-10%. That means that all artists who pursued their careers during the Nazi regime, 90-95%, did so while their “Jewish” colleagues were persecuted and forced into exile. Every artist who managed to leave Germany was replaced by an eager “German” colleague, who approved and exploited the racial measures. Dancer Ilse Meudtner exemplified the “us” versus “them” rhetoric with an internalization of Nazi racial categories, claiming that “it was our turn now.” (Meudtner, 1990, 52)

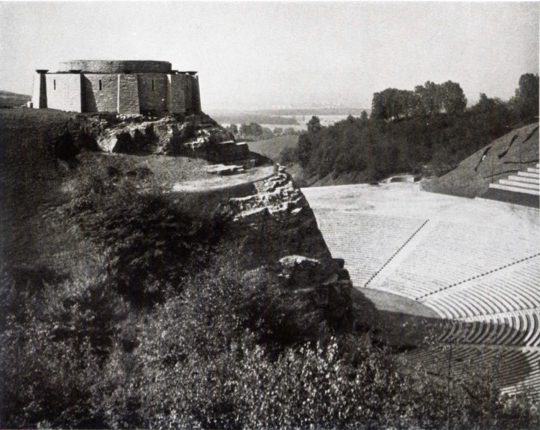

The maintenance of the repertoire, with William Shakespeare and George Bernard Shaw among the most performed playwrights, was only one goal. The other goal was to create a new genre: the Thingspiel “Thing Play,” a multi-disciplinary patriotic spectacle.

The etymology of the term is of importance: Ting or Tie was, according to linguistic studies of the early 19th century, the word for the people’s assembly or the place where Germanic tribes had spoken law, also the thing that was debated or negotiated. The space in which this happened was called the Thingplatz or Thingstätte. It was often a place that was slightly elevated and situated in historically significant areas.

With “immense financial means and human resources” (Simhandl, 1996, 254), the project was officially endorsed in 1934, when Rainer Schlösser, the Reichdramaturg, defined the genre’s fundamental features in his speech the Coming of the Folk Spectacle. Yet only a few years later the Propaganda Ministry withdrew its support.

In response to the first play competition that the Propaganda Ministry launched in 1933, roughly 10,000 plays were sent in. But most were deemed unsuitable and too primitive. Only about 14 pieces were judged good enough to put forward for performance.

The “Thing Play” was supposed to represent the ideal form of a festive, ceremonial play and was to create a cultic popular performance spectacle for the masses. As a mass ritual, it was to reconnect performers and observers to one another and to old Germanic values and enable their incorporation by enacting them.

The content of the “Thing Plays” was driven by ideological concerns. The plays emphasized the forging of the “People’s Community” by embodying it, by playing out the process of becoming part of it.

The topics of many of the plays focused on the heroism and sacrifices of German soldiers in World War I, the coming together of the German people and their desire for a new social form of organization. The shows presented the Weimar Republic as “Jewish,” corrupt and utterly “degenerate”; they resented the democratic, tolerant, and liberal attitudes of the republic. The themes explored heroism in war and conflict, with visions of a rosy future; they offered performers and audiences moments of identification through association with lived experiences which were part of the collective memory, such as the loss of a father or son in battle, imagined as sacrificial death for the fatherland, the economic hardship of inflation and depression, and the struggle towards national unity.

To convey the idea of the “People’s Community” as the perfection of the German nation, its fate and destiny, several existing performance conventions were integrated into the “Thing Plays.” The merging of performers and the audience into a unity of ‘actors’ who celebrated the cultic people’s drama was one aspect that had already shaped the innovative productions during the Weimar years, in Erwin Piscator’s (1893-1966) revolutionary proletarian revues as well as in Bertolt Brecht’s Epic Theater and didactic productions. As committed left wingers, both emigrated and eventually arrived in the United States. But in the “Thing Play” the highly politicized practice was turned into a quasi-religious ceremony, a communal ritual.

Another important aspect lay in the demand for the leader to appear at crucial moments of the drama and disentangle the conflict of the narrative, leading the community towards a resolution. The leader, exemplifying the Führer principle, represented the active element whereas the Volk, “the people,” re-acted and required leadership to establish the new order. Staging was characterized by militaristic configurations, marching on and off stage, the emphasis on rhythmic speaking and the masses moving rhythmically and in unison. The spoken word was only one part of the performances and integrated into the chorus that sang, chanted, and moved together in time. In many ways, the “Thing Play” also owed much to the musical oratorio tradition of the 19th century and in its religious and ritualistic leanings to the passion plays so popular in southern, Catholic Germany and Austria. The plays incorporated pantomimes, allegories, tableaux, and flag ceremonies.

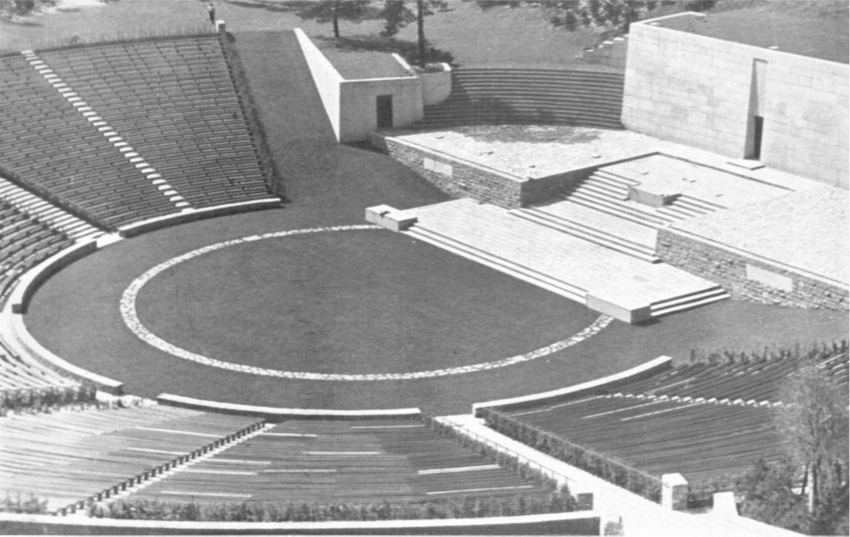

One of the most striking elements lay in the numbers, the audience as well as the performers involved. These were true mass productions that regularly involved tens of thousands of performers and observers. One event, the presentation of one of Gustav Goes’ (1884-1946) plays in 1934 in Berlin, attracted 60,000 people in the audience. These masses were set in contrast to the leader figures. Individual stories became less important; rather, abstract types were presented in tribunals or judgement situations. The underlying narrative stressed the existential need for survival of the community that was taken by the leader towards victory. The average Thing amphitheaters could accommodate on average 20,000 to 25,000 people in the audience and between 3,000 to 5,000 people on stage which made the spaces particularly appealing for Nazi mass rallies.

But the most enduring feature of the “Thing Plays” and a demonstration of the scale that the Propaganda Ministry had in mind lay in the architecture. The first Thing Platz was built near the city of Halle, in Saxony-Anhalt; Propaganda Minister Goebbels opened it on June 5, 1934. Several plays by Kurt Eggers (1905-1943) and Kurt Heynicke (1891-1985) formed the repertoire. Both authors are completely forgotten, their works no longer performed.

Thingstätten were built on ancient battle fields, on prehistoric hero’s graves, or sacred mountains, on sites imbued with some sort of sacred historical spirit. The preferred architectural form emulated the ancient Greek amphitheater with a three-part space. The largest part reached into the audience space, placing the proscenium and auditorium on the same level. The “middle section”, formed the second area and the “backstage,” furthest away, was the third area. It constituted the smallest and highest part, a vanishing point for the leader who could oversee the events and intervene in the narrative at crucial moments.

The Nazis reasoned that this new architectural design erased class distinctions that were embedded in the bourgeois theatre with its boxes, its circles, the pit, ‘high’ and ‘low’ seats, and strict hierarchical associations. The amphitheater harked back to ancient Greece and was supposed to create a sense of unity of the German people. The speaking, chanting, rhythmically moving choirs would enter through wide aisles; they would seem to emerge from the midst of the people and guaranteed a flowing transition from performance to viewing areas. The beginning and end of the plays were often marked by fanfares (similar to Richard Wagner’s operas in his festival theater in Bayreuth).

Of the anticipated 400 Thing sites only roughly 40 were actually built. Can we therefore speak of a failure of the Thing Spiel? Did the whole idea, the concept fail or was its realization too ambitious?

The abandonment of the grand Thingspiel plans of and by the Propaganda Ministry must be understood in the context of its rivals and the politics of competing, polycratic power structures: those of Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring (1893-1946 suicide before execution), responsible for the Prussian State theaters in Berlin or Alfred Rosenberg, the chief ideologue of the Third Reich. Goebbels had to be successful under all circumstances. The Thing Plays proved too expensive in their architectural endeavor and in payments to thousands of workers temporarily released from their jobs for performances, too laden with political performance traditions of the social democratic and communist parties, too Catholic in their ritualistic, quasi-religious orientation and, above all, not suited to modern entertainment.

In the end, Goebbels decided that he would support conventional theater, musical revues, operettas, and light entertainment that offered the perfect escapist route out of politics. They could be watched live and broadcast as well. They reached many more people in the German population than the heavy-handed Thing Plays. For some years Goebbels even fought Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945 suicide), Head of the Police and the SS, over jazz and swing music and dance. (See Karina, Kant, 2003)

The “Thing Play” movement faded away and was succeeded by radio and film as better, cheaper, more modern, and subtler entertainment media. But the model of Thing spectacles as grand political performances continued to be employed in the monumental Nazi mass rallies, during the Nazi Party Congresses, during special events such as Hitler’s or Goebbels’ speeches, or during the commemoration of historically significant moments. The choreographies of thousands of people, many in uniform to the sounds of trumpets and fanfares, the ritualistic celebrations with flags, fire and Nazi symbols defined the mass rallies as well as the theater plays until 1945. These principles were never given up and we can observe them in Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph of the Will in 1934, and then two years later, in the opening ceremony of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin.

The venues, the Thing sites, exist to this day and are used for open-air performances. Do they still carry the spirit of Nazi rituals or has that past been thoroughly erased?

The “Gleichschaltung” of Music

Adolf Hitler had harbored ambitions as a painter and later transferred them to architecture. With Albert Speer (1905-1981), who served as Berlin’s General Building Inspector from 1937 to 1942, and Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production from 1942 to 1945, Hitler planned to raze and rebuild the capital Berlin as Germania. But above all, Hitler had a never-ending love for the music of Richard Wagner. “I was immediately addicted. My youthful enthusiasm for the Bayreuth Master knew no bounds.” (Hitler, 1943, 15) Hitler called Wagner “the most prophetic figure the German Volk ever possessed” (Rauschning, 2005, 216). He saw in Wagner’s writings and musical compositions a cultural philosophy for Germany that had to be translated into political action.

In several essays written after the incomplete revolution of 1848 (Art and Revolution, 1849, The Work of Art of the Future 1850, Judaism in Music 1850/1869, Opera and Drama 1851) Wagner outlined a methodology that set the German Volk against the “Jew.” He suggested an approach towards the creation of art that would rescue true national, German values, and secure a great future. Wagner’s inflammatory pamphlet on Judaism in Music was the first systematic evaluation of the cultural evolution of a people and cultural policies based on racial criteria and rooted in antisemitism. Wagner’s essay outlined how aesthetic arguments could be used for an ideology that focused on race. He discussed how artistic aspects represented deeper characteristics of a nation and a people. He traced his ideas from mere observations within a social context to possible political and aesthetic realizations.

In several essays written after the failed revolution of 1848 (Art and Revolution, 1849, The Work of Art of the Future 1850, Judaism in Music 1850/1869, Opera and Drama 1851) Wagner outlined a methodology that set the German Volk against the “Jew” and suggested an approach towards the creation of art that would rescue true national, German values, and secure a great future. Wagner’s inflammatory pamphlet on Judaism in Music was the first systematic evaluation of the cultural evolution of a people and cultural policies based on racial criteria and rooted in antisemitism. Wagner’s essay outlined how aesthetic arguments could be used for an ideology that focused on race. He discussed how artistic aspects represented deeper characteristics of a nation and a people. He traced his ideas from mere observations within a social context to possible political and aesthetic realizations.

Wagner’s racialization of music needed hardly any further enhancement and was used as a blueprint for all aesthetic assessment by the Nazis. Anything that fit within a broad Wagnerian vision was appealing, anything that contradicted or questioned it had to be eliminated as “Jewish.”

Like the Propaganda Ministry and other cultural institutions that continued to pursue Nazi racial politics in music and theater, the Rosenberg Office classified and assessed all new compositions, including symphonic works, operas, songs, incidental music, film music, etc. It coordinated contact between party and governmental offices (often as a challenge to Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry) and offered guidance and leadership to the Music Council of the German Educational Board, that determined what material could be used in schools and higher education. It intervened in the consultation and selection of artists for specific commissions, observing and analysing performance tendencies to control, and if necessary, forbid them. It waged a constant war against Goebbels and the Propaganda Ministry that led to an increase in antisemitic rhetoric and action on all sides.

In 1933 Herbert Gerigk (1905-1996), employed by the Rosenberg Office, headed by chief ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, declared that “Not the degree of talent must alone determine the assessment of an artist but first and foremost it is his blood and belief.” (Gerigk 1933).

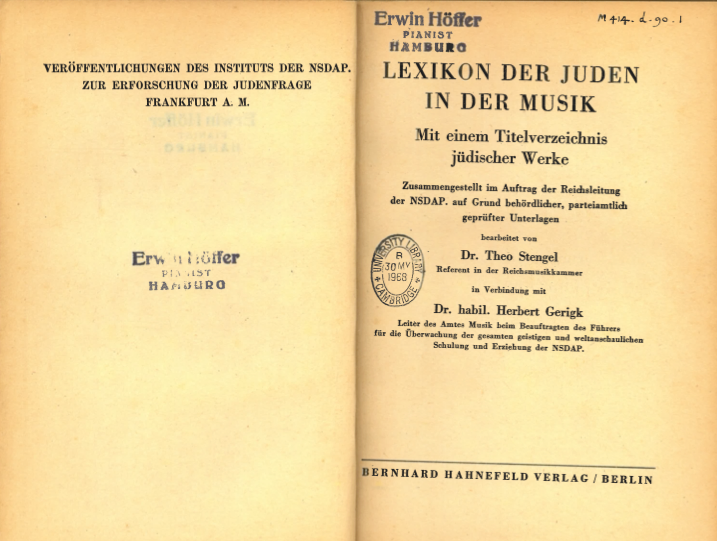

Gerigk also worked together with an employee of the Reich Music Chamber, Karl Theophil Stengel (1905-1995) on the Lexikon der Juden in der Musik “Encyclopedia of Jews in Music”, published in 1940. It included musicians, musicologists, music teachers, librettists, conductors and music publishers, “Jews”, so called “half-Jews”, and their works. It ran to 404 pages in its last edition in 1943.

Joseph Goebbels’ Ten Basic Tenets of German Musical Creation followed Wagner’s and Hitler’s dictum. In 1938 he summarized the principles that German music should follow. It should concentrate on melody, honoring the past, tradition and the Wagnerian heritage; it should battle for a German and fight against an “un-German music.” It should engage in the concept of the Heimat “homeland” and reject the idea of alienness or internationalism, i.e., intellectual and cultural “homelessness.” It should explore folkish characteristics, protect them against foreign influences and find the deep forces that were rooted in folkishness.

In practice that meant that composers were to cultivate 19th century tonality and emphasize the relationship between melodic and harmonic interaction. They should reject unresolved dissonance as a musical principle and anything that sounded like jazz and swing with its syncopations (invented by black and “Jewish” musicians) and reject the twelve-tone-system of Arnold Schönberg and his students, who became prototypes of a “Jewish” compositional style.

Goebbels referenced Wagner directly when he reminded musicians that “the battle against Judaism in German music, once fought by Richard Wagner all on his own, is now the grand and never to be relinquished task of our time, now to be taken up by an entire people… Judaism and German music are antagonisms that, by their very nature, stand in strictest opposition to one another.” (Goebbels, 1938, 1)

But these guidelines, as those for the other art forms, always depended on interpretation; it was up to the composers, conductors, and musicians themselves to label a work as “Jewish” and “degenerate” or “German” and thus acceptable. Composers — such as Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) were immediately banned for the satirical, ironic, and “acidic” “Jewish” stance they took. That, according to Wagner, undermined the integrity of the fabric of German art. Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847) and Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) had been named by Wagner as examples of “Jewish” corruption and debasement of everything German in the essay Judaism in Music. According to Wagner, these Jews were not capable of inventing; they had to steal from German masters. And so the artists in Nazi Germany complied and erased these and many other composers from the musical canon and repertoire. Where the works were too well-known and too beloved by the public, the names of the creators were expunged. Another strategy lay in the commission of new compositions. Carl Orff re-composed one of Mendelssohn-Bartholdy’s most famous pieces, the incidental music for Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1939 after the Propaganda Ministry invited composers to do so. Often the old text would be replaced with new words without fundamentally altering the original libretto. This path was adopted in the case of many operettas and pop songs. In this way, a popular tune could be preserved yet the “Jewish” influence seemingly removed – by silence and non-acknowledgement.

Cultural historian Peter Paret reminds us that “beneath a facade of constantly asserted uniformity, the regime was made up of different, often competing elements.” And he goes on to stress that “the traditionally high standard of concert and opera performances in Germany made the medium a particularly important instrument of cultural propaganda, both at home and internationally.” (Paret, 2006)

This comment underscores the self-perception of the Nazis and their regime as legitimate because of the great cultural legacies they claimed; it also highlights the contradiction of the “Kulturnation” “nation of culture” and its barbarism. At the same time as operas were performed by the German public and concerts enjoyed by an audience in the occupied territories, the plan to annihilate European Jewry was hatched.

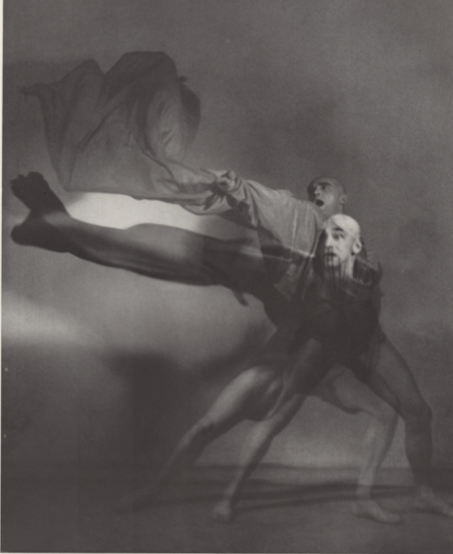

The “Gleichschaltung” of Dance: German Dance, the Movement for the Third Reich

Of all the art forms, it was German Dance that most outspokenly and deliberately attacked the historical performance tradition on which it rested. Its founder, Rudolf von Laban (1879-1958) and his most important student, Mary Wigman (1886-1973) declared ballet, the predominant movement aesthetics in theaters and opera houses, “outdated,” “decadent” and “racially essentially alien” (Wigman, 1929 12f). That attitude seems to run counter to the Nazi belief in history and avowals of legitimacy based on historical trajectories. But in this case, the complete erasure of previous dance history, deemed alien and foreign, and the invention of a new dance guaranteed the incorporation of an entire art form into Nazi culture.

If ballet had stagnated and could not provide a basis for further development, then “dance had to be created anew” (Laban, 1920, 24). Laban, often called the father of modern dance, created it as a new “religion of the act” (Kant, 2002, 44); by 1920 he declared it a “practical religion” (Laban, 1920, 244). Laban’s theory rested on a quasi-religious interpretation of the world. It combined occultism, Catholicism, Masonic rituals, Neo-Platonism – the belief that humanity had to redeem itself by moving according to the natural laws of harmony that Laban thought he had uncovered. This was (and in many ways still is) a sectarian movement with all the attributes and characteristics of cultic behavior. Precisely these characteristics fascinated the Nazis.

Laban anchored his movement system in a specific social space and tied it to a specific concept of movement time. Laban’s dance was “invented tradition” (Hobsbawm, 1983) that rejected not only historical heritage but history per se, and declared itself a necessary replacement of everything that had happened before. It addressed and invited all lay people as well as professionals to partake in the rituals so that humanity could emancipate itself from the shackles of civilization.

Laban’s system of movement and dance was developed systematically over a period of several decades; by the early 1920s, when he settled in Germany, most elements were in place or at least sketched. He offered his thoughts to the public in 1920 in his first major book, Die Welt des Tänzers “The World of the Dancer”. Many more publications were to follow. His is a predetermined movement system that functions as means towards its own end. Ballet technique, on the other hand, must fulfill the opposite: it is the means toward an end – the evening performance in the opera house. Ballet technique is learnt but then will be interpreted and re-defined by every choreographer. Laban’s dance did not (and does not) have this flexibility. It cannot be criticized and altered for performance needs.

Laban considered his contemporary world of the Weimar Republic with its democratic ambitions to be sick, “degenerate” and in need of a cure. This cure had to be focused on movement as means of purification as much as restoration to strength, health, and beauty. His movement system would offer a Christian and racialized revitalization to those who practiced it. Only by dancing could a better future be achieved.

His theory and his practice were unusual and became compatible with the Nazi regime because he devised his aesthetic categories along folkish thought. He conceived of his dancing groups and “Movement Choirs” as communities separate from society. The community/society and civilization/culture debate broke out around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century . It was in favor of a coherent, usually homogenous community, rather than the divisive and alienating civil society. Society produced civilization, but only community could generate culture – a national and true people’s culture. Laban built this community as a dancing commune and would later find no problem with a slight re-orientation towards the “German People’s Community” of the Nazis.

One of the powerful folkish ideas that Laban took up and integrated into his movement system concerned the space in which he placed his dancers: he called it Lebensraum, “the living space” of the community. Lebensraum was the term used to denote the new space that the Germanic, “Aryan race” required to survive the onslaught of the “degenerate” races. It became a component of racial ideology and drove the expansion politics into Eastern Europe. It can be called a form of settler colonialism and was developed by Friedrich Ratzel (1844-1904), then further advanced by Karl Haushofer (1869-1946). According to this theory, the growth of all species is primarily driven by their conquest of and adjustment to geographic spaces that also define cultural and social adaptation.

Laban’s living space was devised as a crystal, a Neo-platonic representation of a better and more spiritual world constructed according to his own harmonic laws of the cosmos. Every Laban-dancer learnt to move within this crystal and learnt to connect the sacred points by executing movement scales and diagonals. Laban rejected the logic and the space of the theatrical stage and had to find new boundaries and definitions; he divided his movements into tiers of high, middle, and low.

According to Laban’s teachings, his contemporary world could only be healed by finding a new Lebensraum for his community. That space was to be found in this real world but also a spiritual world beyond. Through dancing the community would atone and find redemption; it would enter eternal life.

Laban organized the dancing community around a chosen charismatic leader (himself) who had the knowledge, often secret, of the cosmos to lead the group and ‘sub’-leaders who had been trained and prepared by the ultimate leader to guide and organize the life of the community. This hierarchy ensured that all theoretical aspects and elements were internalized by the community, that the complete belief system was unconditionally accepted by all members of the group. The expression of a “self” was not that of the independent individual within capitalist society but a strictly communal self, the self that only functions and finds its meaning within the community.

In German Dance, community and rhythm were biologically determined factors and forces. They had to be felt internally and experienced as rhythm of the body, of blood pulsing, of inhaling and exhaling, of arms swinging and legs walking. The biological definition of movement took up and continued the racial discourse of the 19th century in eugenics. Laban deliberately incorporated the social Darwinist approach to social organization and reformulated conservative and right-wing ideologies for modern dance as concrete aesthetic categories.

In Switzerland Laban had belonged to an occult masonic lodge founded by Theodor Reuss (1855-1923). Laban continued to cultivate these occult masonic connections but also turned to outright folkish organizations when he relocated from Switzerland to Germany in 1919. Laban was testing and realizing his theory and at the same time he was exploring larger social applications. He had contact with the Vortrupp Bund, a conservative folkish umbrella organization that wanted to further “Germanness” in German culture and gave speeches on the “unhealthy intellectual way of life.” (Köhler 2017, 245). In 1922 he visited and set up summer camps in Gleschendorf and the Siedlung Klingberg (Puschner, 1996), a settlement that promoted the breeding of a ‘pure Germanic race’ with an equivalent way of life. There he choreographed summer solstices and became interested in the swastika as a choreographic symbol. In Gleschendorf he also was introduced to the fascist secret society, Order of the New Templars, also known as Ordo Novi Templi (ONT), and the “Thule Society” both notorious antisemitic, folkish-racist organizations.

Laban thus thought tactically and strategically about the implementation of his dance ideology and directed his dance endeavors toward social reform and social revolution by associating with right-wing, Germanic movements and integrating them into the conservative and reactionary racial modernist projects. Laban’s model for a German art, in his case German Dance, also took Wagner’s total work of art as model and point of departure (he had choreographed the Tannhäuser Bacchanale in Bayreuth in the early 1930’s).

Dance became a “racial question” long before the Nazis came to power. Fritz Böhme (1881-1952), one of Laban’s students and disciples, simply found a suitable phrase and turned it into a political slogan in 1933 that advertised the concept as well as the terminology “German Dance” and offered it to the Nazi administration. After World War I, according to Laban, dance had to help rescue the Western world by removing civil society and replacing it with the values of a dancing community. After 1933 it took the next step and became part of Nazi aesthetic politics while enacting the “People’s Community.” Laban was also enchanted by the “Thing Play” movement and wished to participate in it.

Like many other dancers of the modern German persuasion, Laban considered the Nazi regime the ideal political system to realize his grand plans. That is why he and many of his students accepted high positions in the cultural administration and began to translate their theories into practice on a scale they could never have dreamed of before the rise of Hitler. That does not make them lesser artists; therein for many admirers lies the problem: how can great artists be affiliated with Nazism and racism? The short answer is they can.

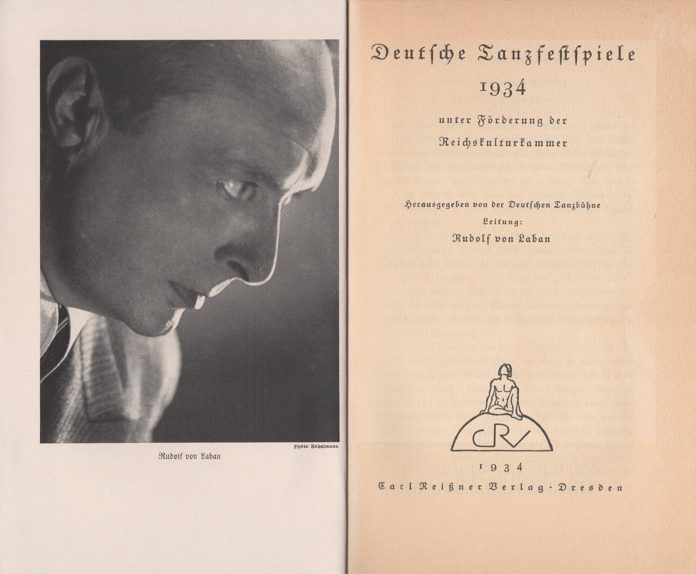

Laban’s success culminated between 1933 and 1937. With the ascent to power of the Nazis, Laban found the strongest support he could imagine. In exchange he supported the Nazi political program – as an artist, theorist, and ideologue. He became an employee of the Propaganda Ministry, as the ‘leader’ of German Dance. He reorganized the entire dance landscape in the German Reich according to the principles that he had developed in the 1910s and 1920s and that Goebbels and the Nazi administration gratefully accepted and implemented.

Laban founded the Deutsche Tanzbühne “German Dance Stage”, a new state sponsored theater. He founded the Deutsche Meisterwerkstätten “German Master Work Shops”, a state-sponsored Dance Academy to train professional dancers.

He reorganized and centralized all dance schools and implemented a new central training and examination program. All dance schools, professional or amateur, had to adhere to these new regulations. He took tight control over all teaching of all dance forms in the German Reich. He instigated regular, annual dance festivals.

He began to reorganize social dance according to his own folkish vision. Social dance, the Foxtrot, Charleston and Quickstep would be replaced with his movement choir exercises. Even though he whole-heartedly supported the Nazi ban on jazz and swing music and dance in 1935, this goal remained incomplete; he ran into strong resistance from the social dance teachers.

The replacement of all “un-German” ballet with his own “German Dance” also remained incomplete, due to the resistance of the ballet dancers, choreographers and, above all, composers like Richard Strauss.

Laban accepted the new structure that the Propaganda Ministry had erected with the Reich Culture Chamber and insisted that “German Dance” was the true artistic movement that represented the political movement of the Nazi revolution. He accepted the racial ideology that was only marginally more extreme than his own views and he accepted the exclusion of Jews from German public life. His refusal to let children defined as “Jewish” study at dance schools and the State Opera Berlin are among the many examples of his own anti-Jewish stance.

His emigration in late 1937 was a result of his miscalculations regarding his own leadership and his own importance. In Great Britain, Laban managed to further implement his ultra-conservative and racist ideas and they became part of secondary curricula and university education.

The End

The Allied bombings of Berlin at the end of 1944 and during the winter months of 1945 turned much of the government district into rubble. The Propaganda Ministry was hit by a bomb and destroyed in March 1945.

Already in February 1945, during the Yalta Conference, the “Dismemberment” and Allied Occupation of Germany by the UK, the US, the Soviet Union, and the French Republic was agreed. That plan was put into practice with further explanation written into the June 5, 1945 Declaration Regarding the Defeat of Germany and the Assumption of Supreme Authority by Allied Powers. The second sentence reads: “There is no central Government or authority in Germany capable of accepting responsibility for the maintenance of order, the administration of the country and compliance with the requirements of the victorious Powers.” That meant that the authority of the Propaganda Ministry had been abolished and its ideological supremacy had ended. The Allied Forces took over all powers of government on state, municipal and local levels.

But more needed to be reconstructed than buildings and ministerial palaces. As The Berlin (Potsdam) Conference recognized in July and August 1945, the German population had to be convinced of its total military defeat and that it would be made responsible for the devastation it wrecked on the world. The Allies specifically demanded the destruction of the National Socialist Party and all its institutions. None of the Nazi administrations, ministries and party offices were to survive. German reconstruction was dependent on the total defeat and removal of the Nazi racial ideology. Just as the program of Nazification had begun in January 1933, so a program of Denazification had to be imposed on the Germans.

Most Germans did not accept it and subverted it whenever and wherever possible. Few artists were made responsible, most were exonerated – because they had “only” been artists. There were a few exceptions: Albert Speer was put before the Nuremberg Tribunal for war crimes and crimes against humanity, not as Hitler’s architect but as minister or armament. He was spared the death penalty and imprisoned in Spandau Fortress. Leni Riefenstahl went through four denazification procedures before being classified as nothing more than a Nazi “fellow traveler.” But her films glorifying the Nazi regime haunted her for the rest of her life. Like Rudolf von Laban or Gustav Gründgens, she refused to acknowledge her role in the making of a Nazi ideology and a Nazi aesthetic. Arno Breker too was denazified as nothing worse than a Nazi “fellow traveler.” He portrayed himself as a victim rather than an ideological perpetrator. His weakness, even sickness, he claimed, was his admiration for the monumental. (Müller 1979)

We are left with works of art created during the Nazi regime and must ask ourselves what to do with them. They cannot be simply banned or erased yet they should not be displayed or exhibited without comment. The architecture of the Thing spaces still exists, as do many of Speer’s buildings or Breker’s sculptures. Strauss’s and Orff’s compositions are performed as staples of concert programs. Orff’s Carmina Burana is beloved by choirs and audiences. The academic discipline of Dance Studies and dance therapy in the UK and the US have fully embraced Laban’s philosophy, without any examination of his role in the Nazification of dance and the historical circumstances that allowed the collaboration of German Dance with the Nazis. These works need to be understood in the context of art celebrating — and made by — accepting and furthering Nazi racial ideology, philosophy, politics, and aesthetics. We must not forget or suppress the aesthetic concepts and practices, but actively remember and acknowledge the foundation on which they were created and assess them accordingly. “National Socialist art is thus not unproblematically ‘beautiful,’ not merely devoted to perfect forms and empty content; it is also imminently brutal, an art based on convictions which, when realised, literally left corpses in their wake.” (Hermand, 1992, 233)

Illustrations

Unless otherwise indicated, third-party texts, images, and other materials quoted in these materials are included on the basis of fair use as described in the Code of Best Practices for Fair Use in Open Education.

References

Adam, Peter. (1992) Art of the Third Reich. London: Thames & Hudson.

Barron, Stephanie. (1991) “Degenerate Art”. The Fate of the Avantgarde. Los Angeles County Museum of Art/New York: H.N. Abrams.

Benjamin, Walter. (1974) Über den Begriff der Geschichte. In: Illuminationen. Ausgewählte Schriften. Vol.1. Frankfurt am Main.

Dümling, Albrecht, Peter Girth. (1988) “Entartete Musik”. Eine kommentierte Rekonstruktion der Düsseldorf Ausstellung von 1938. Düsseldorf: Landeshauptstadt, Düsseldorfer Symphoniker.

Dümling, Albrecht. (1989) Entartete Musik: Eine Tondokumentation zur Düsseldorfer Ausstellung von 1938. Frankfurt/M: Zweitausend Eins.

Dümling, Albrecht. (2011) “Entartete Musik.

Etlin, Richard A. ed. (2002) Art, Culture and Media under the Third Reich. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fritzsche. Hans. (1934) Dr Goebbels and his Ministry. In: Hans Heinz Sadila-Mantau, ed. Deutsche Führer, Deutsches Schicksal: Das Buch der Künder und Führer des dritten Reiches. Berlin: Henius.

Goebbels, Joseph. (1933a) The Tasks of the Propaganda Ministry. Speech to representatives of the German Press, 15 March 1933.

Goebbels, Joseph. (1933b) Speech to the Intendants and Directors of Radio Stations, Berlin, 25 March 1933.

Goebbels, Joseph. (1938) Amtliche Mitteilungen der Reichsmusikkammer. Vol.5., no.11.

Hermand, Jost et al. (1992) Old Dreams of a New Reich. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hitler, Adolf. (1943) Mein Kampf. Munich: Franz Eher Nachf.

Hobsbawm, Eric, Ranger, Terence. (1983) The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen ed. (2006) Bauhaus Culture: From Weimar to the Cold War. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kant, Marion. (2002) Laban’s Secret Religion. In: Discourses in Dance. No.1 issue 2.

Karina, Lilian, Kant, Marion. (2003) Hitler’s Dancers. German Modern Dance and the Third Reich. Oxford, New York: Berghahn.

Kershaw, Ian. (1998) Hitler. London: Penguin.

Köhler, Kristina. (2017) Der tänzerische Film. Frühe Filmkultur und moderner Tanz. Marburg: Schüren

Krohn, Claus-Dieter ed. (1998) Handbuch der deutschsprachigen Emigration 1933 – 1945. Darmstadt: Primus-Verlag.

Laban, Rudolf von. (1920) Die Welt des Tänzers. Stuttgart W. Seifert.

London, John, ed. (2000) Theatre Under the Nazis, Manchester, New York: Manchester University.

Mann, Klaus.(1936) Mephisto. Amsterdam: Querido.

Meudtner, Ilse. (1990) Tanzen konnte man immer noch. Berlin: Hentrich.

Mosse, George. (1964) The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. New York: Grosset & Dunlap.

Müller, Andre. (1979/2006) The monumental is my sickness. Interview with Arno Breker.

Paret, Peter. (2006) Review of Hans Sarkowicz. Hitlers Künstler: Die Kultur im Dienst des Nationalsozialismus. Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 2004.

Puschner, Uwe et al, ed. (1996) Handbuch zur “Völkischen Bewegung” 1871-1918. Munich New Providence, London, Paris: K.G. Saur.

Rauschning, Hermann. (2005) Gespräche mit Hitler. Zurich: Europa Verlag.

Röder, Werner, Strauss, Herbert A. (1999) Biographisches Handbuch der deutschsprachigen Emigration. International biographical dictionary of central European emigrés, 1933-1945. Vol. 1. Munich, New York: Saur.

Simhandl, Peter. Theatergeschichte in einem Band. Berlin: Henschel 1996.

Spotts, Frederic. (2003) Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. Publishers Weekly. Released January 1st.

Steinweis, Alan E. (1993) Art, Ideology, and Economics in Nazi Germany: The Reich Chambers of Music, Theater, and the Visual Arts. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Stengel, Karl Theophil and Gerigk, Herbert. (1940) Lexikon der Juden in der Musik, (Encyclopedia of Jews in Music). Berlin: Bernhard Hahnefeld Verlag.

Stommer, Rainer. (1985) Die inszenierte Volksgemeinschaft: die “Thing-Bewegung” im Dritten Reich Marburg: Jonas.

Wigman, Mary. (1929) Das Land ohne Tanz. In: Die Tanzgemeinschaft.Vierteljahresschrift für tänzerische Kultur. No.1, issue 2.

Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, also called Propaganda Ministry, founded on 13 March 1933 with Dr Joseph Goebbels as Minister, with its seat in Berlin. It was bombed in an Allied attack in 1945 and dissolved on 5 June 1945. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2022

Reich Chancellery. The seat of the Reich Chancellor of Germany, a synonym for the seat of power. German Historical Institute, 2022

Reich District. Regional administrative unit in the Third Reich. German Historical Institute, 2008.

The government agency of the Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda to supervise and control the arts, founded by decree on 22 September 1933. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2022

Degenerate Art. Application of a biological term to the arts. Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum, 2022

Meaning “leader,” the title used by Adolf Hitler to define his role of absolute authority in Germany’s Third Reich (1933–45). Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022

“People’s Community.” Term given to the ideal, racially cleansed German social order. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022

(Living Space) Space for the nation and Germanic race to expand. BBC and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

A total work of art, an aesthetic concept developed by the philosopher K. F. E. Trahndorff (1782-1863) and further advanced from 1849 by composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) that denotes a synthesis of all arts. Wikipedia, 2022

A position created within the Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda to inspire and coordinate cultural and artistic production in the Third Reich. Wikipedia, 2022

Can be translated into English as “nation of culture.” The term denotes a nation or a nation-state that has united social groups into cohesive entities that are linked through language, culture, religion, and shared tradition. The construction of such shared culture is vital for instilling feelings of patriotism and national sentiment. The concept arose towards the end of the 19th century in Germany and expresses cultural nationalism. Wikipedia, 2022

Epic Theater. Performance Theory developed by Bertolt Brecht, discussed in the early 1920s and applied in his Lehrstücke “teaching plays.” The British Library, 2022

Thing Play, a new performance genre, developed after 1933; with Thingplatz or Thingstätte, the space where the Thingspiel happened. Wikipedia

Order of the New Templars. A Fascist secret society in Germany founded by Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels Wikipedia

Also known as the Crimea Conference, this February 1945 meeting was held by the leaders of the United States, the Soviet Union, and United Kingdom to discuss the post-World War II reorganization of Europe. Yale Law School: The Avalon Project See also: Office of the Historian

The Big Three Allies - Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (replaced on July 26 by Prime Minister Clement Attlee), and U.S. President Harry Truman-- met in Potsdam, Germany, from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to negotiate terms for the end of World War II….and determine the postwar borders in Europe. Office of The Historian