Aftereffects

Denial, Distortion, and Dis/Misinformation

Lara Martin Lengel; Desiree Montenegro; and Victoria Ann Newsom

In his book, Less than human: Why we demean, enslave, and exterminate others, David Livingstone Smith (2011) notes, “The Holocaust is the most thoroughly documented example of the ravages of dehumanization” (p. 16). Even so, denial and distortion are an ongoing problem, compounded by disinformation and misinformation. This chapter will define Holocaust denial and Holocaust distortion, explain some motivations for denial and distortion, and analyze several contemporary examples of erroneous information which can be related to the phenomenon of "fake news".

Defining and Differentiating Terms

While there have been various definitions and conceptions of Holocaust denial and distortion, the most comprehensive and widely accepted definition was established by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA, 2013), an association of 31 countries dedicated to perpetuating the memory of the Nazi genocide. It reads:

“Holocaust denial is a discourse and propaganda that deny the historical reality, and the extent of the extermination of the Jews by the Nazis and their accomplices during World War II, known as the Holocaust or the Shoah. Holocaust denial refers specifically to any attempt to claim that the Holocaust/Shoah did not take place.

Holocaust denial may include publicly denying or calling into doubt the use of principal mechanisms of destruction (such as gas chambers, mass shooting, starvation and torture) or the intentionality of the genocide of the Jewish people.”

Distortion of the Holocaust is defined by the IHRA (2013) as:

- Intentional efforts to excuse or minimize the impact of the Holocaust or its principal elements; including collaborators and allies of Nazi Germany;

- Gross minimization of the number of the victims of the Holocaust in contradiction to reliable sources;

- Attempts to blame the Jews for causing their own genocide;

- Statements that cast the Holocaust as a positive historical event. Those statements are not Holocaust denial but are closely connected to it as a radical form of antisemitism. They may suggest that the Holocaust did not go far enough in accomplishing its goal of “the Final Solution of the Jewish Question”;

- Attempts to blur the responsibility for the establishment of concentration and death camps devised and operated by Nazi Germany by putting blame on other nations or ethnic groups.”

Denial spans a spectrum from more subtle discursive patterns to outright denial that the Holocaust did not occur at all (IHRA, 2019; Long, 2002; Rossoliński-Liebe, 2012; Shermer & Grobman, 2000). To provide context for forms of denial, Dr. Deborah Lipstadt (cited in United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, USHMM, 2016), one of the foremost scholars on the subject, differentiates levels of denial in terms of hardcore and softcore deniers. Hardcore deniers claim the Holocaust did not occur, while softcore deniers confirm the Holocaust happened, but pose questions regarding the number killed, or claim that the gas chambers were not used. In 2022, Dr. Lipstadt was confirmed by the U.S. Senate to serve as Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism.

Motivations and Strategies for Holocaust Denial and Distortion

Deborah Lipstadt notes that there is only one reason to deny or distort historical facts about Holocaust: “to inculcate and foster antisemitism” (cited in USHMM, 2016). However, there are many strategies and tactics that as used in Holocaust denial and distortion. Acknowledging the many variations from outright denial to Holocaust distortion, researchers have identified numerous strategies including comparative Holocaust trivialization, a strategy that has been used by, among others, political leaders from East Central Europe. Trivialization can encourage “organized forgetting,” in order to avoid facing “collective incrimination” (Shafir, 2002, p. 3), “deflective negationism” to deflect blame from one’s own nation, and “strategic revisionism.” These efforts, like propaganda and denialism of many sorts, may (sometimes intentionally) lead to problems that may be described as cultural misrepresentation (Polgar 2019, 86).

Communist regimes in East Central Europe, for instance, engaged in “de-Judaization” of the Holocaust, nationalizing the political discourse about Nazi atrocities, focusing on harm to the nation rather than systemic antisemitism, making “the task of Holocaust negationists easier (Shafir, 2002, p. 4). Examples include the removal or absence of language on memorials honoring Jewish communities who were killed or otherwise harmed by the Nazis, or by using only phrases like “the Polish people” broadly, when the Holocaust was a genocide specifically targeting Polish people of Jewish heritage.

Furthermore, according to the editor of the American Historical Review (2018), “Holocaust deniers like David Irving wrap their ideology in the cloak of historical objectivity in order to get dangerous falsehoods accepted as objective ‘truth’ by credulous readers” (para. 6). These calculated, strategic, and deliberative efforts distort and suppress historically accurate realities. They redirect the narratives that acknowledge the injustices that have ravaged certain ethnic and cultural groups or that justify reparations. Accepting such false revision can set a precedent, suggesting that all injustices may be re-defined or even erased from our history and time.

Historical Contexts

Holocaust denial and distortion have extensive histories that are linked to both historical antisemitism and antisemitic Nazi propaganda. Hitler and Joseph Goebbels renewed the defamatory term Lügenpresse or “Lying Press” that dated back to the mid-1800s.

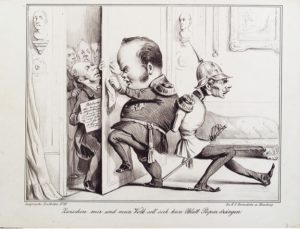

Image 1: “Zwischen mir und mein Volk soll sich kein Blatt Papier drängen” “There shouldn’t be a sheet of paper between me and my people”

The term Lügenpresse appeared in print in 1914, in Reinhold Anton’s “The Lying Press: The Lies Campaign of Our Enemies: Another Comparison of German and Hostile News.” The term appeared again in 1918, when international media organizations reported that Germany was likely to lose the World War I. The War Press Office of the Bundesverteidigungsministerium “Federal Ministry of Defense” released the similarly titled book, Die Lügenpresse unserer Feinde, that targeted international media as “enemy propaganda.” Like its usage during the First World War, the term Lügenpresse was intended to counter what the Germans determined to be allied propaganda campaigns. Historical accounts have since confirmed that a substantial amount of such allied “propaganda” was accurate (Frankl, 2019; See, also, The Economist, 2016a; 2016b; Haller, & Holt, 2016; 2017).

Just over a decade later, the term Lügenpresse was used in a stigmatizing way to provoke hatred against Jewish people and communists, both within and outside Germany. Critics of Adolf Hitler’s regime were frequently referred to as members of the “Lügenpresse apparatus.”

Under the direction of Joseph Goebbels, a writer who became Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda in Nazi Germany, the defamatory term Lügenpresse was renewed and frequently used to scrutinize, vilify, attack, blame, and undermine the trust in reputable, established German journalists and media organizations (Holt & Haller, 2017). The term Lügenpresse was also used to claim that the media was Jewish-dominated.

The Nazis first criticized and then (once in power) shut down competing (non-Nazi) news organizations, along with any organizations that were critical of the Hitler and the idea of a Third Reich. Lügenpresse was also used condemn the international press that reported anything unfavorable about the Nazi regime. Hitler called international press coverage “atrocity propaganda.”

Even before he rose to power Hitler, Goebbels, and others, used this pejorative term to claim the press was Jewish-dominated. This proved a successful rhetorical strategy: vilification of the ‘lying’ press and using slogan “Lügenpresse apparatus.” Dr. Richard Frankel (2019, p.3) notes the notion of a Jewish-biased press “stretched back decades. By the 1920s it was all but an unspoken assumption within German antisemitic circles. So now, if the press was critical of the Nazis, the explanation was clear: the Jews. And since, according to Hitler, Jews were fundamental enemies of Germany, the press, too, was the enemy of the people.”

From Lügenpresse to “Fake News”

The term Lügenpresse made a disconcerting reappearance in 2014 in the context of an increase of immigrants to Germany seeking asylum from oppression in Syria. Analysts find it in PEGIDA (Patriotische Europäer Gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes)(Beiler & Kiesler, 2018; Haller & Holt, 2016; 2019; Koliska & Assmann, 2019). Then, in 2016, when two supporters at a Trump campaign rally shouted the term at the press in attendance to cover the rally (Nesbitt, 2016).

The increase of reports of verbal and physical attacks on journalists and media organizations by alt-right individuals calling them Lügenpresse increased public discourse about the disturbing history of accusations of “fake news” in Germany (Koliska & Assmann, 2019). The resurgence of the term signaled concern by contemporary German citizens who are aware of the use of the defamatory term as an anti-democracy strategic narrative by Nazis and, later, by the East German government (Noack, 2016). Lügenpresse was awarded the annual “Unwort des Jahres” by a panel of linguists in Germany, after PEGIDA and other organizations, such as Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, AfD), used it frequently to discredit reputable journalists (Chandler, 2015; Kirschbaum, 2015).

Many experts on World War II and the Holocaust have made a connection between certain strategies of former U.S. President Donald Trump and those used in Nazi Germany. Comparisons include, but are not limited to, vilification of reputable media organizations. What Hitler and Goebbels labeled Lügenpresse, Trump identifies as “fake news” adding fuel to public dissent and fostering distrust of credible media outlets. One consequence can be the popularization and consumption of underground media as a primary trusted source of information (Eberl, 2019; Woeste, 2017).

Not only are denial and distortion narratives promoted by dubious media sources, but information containing historical facts about the Holocaust may be aggressively labeled “fake news” by those on the political right in the U.S. and Europe. There are a variety of styles of Holocaust denial and distortion that are promoted as strategic narratives for audiences in right-of-center demographic groups. Deniers sometimes promote the idea that the genocide was not deliberate, suggesting Jewish people in Europe were merely negatively impacted by the of hardships of war. Denial also tries to cast doubt upon the existence of the gas chambers, sometimes fabricating statistics and other times pointing out discrepancies that may be simply related to approximation in reports of the numbers of casualties (Ochab, 2020; Southern Poverty Law Center, 2019).

How Disinformation Leads to Hate Crimes and Bias Incidents

Scholars and political scientists have long argued that Holocaust denial leads to a rise in antisemitic activity (Asfari & Hirschebein, 2018; Feingberg, 2020; Lobba, 2017; McElligott & Herf, 2017; Tye, 2020). Contemporary Holocaust denial and distortion are visible in various contexts and strategic narratives through the world today in many forms including, but not limited, to conspiracy theories, alternative truths, “fake news”, underground media, and hate groups. It grows in popularity on public forums with little to no oversite, inciting hate crimes, attacks on synagogues, verbal abuse or hate speech and abusive memes on social media (Woeste, 2017). Particularly problematic is increasing hate speech in social media, which can foster increases in antisemitic bias incidents and hate crimes, and also harm community trust and security.

The assumed anonymity of digital spaces furthers the spread of propaganda and misinformation, resulting in the proliferation of real and imagined extremist narratives (Daniels, 2018; Kellner, 2017). While not everyone who resends extremist propaganda and rhetoric are part of the extremist group, curiosity and lack of awareness may draw people to a particular online report, video, or image that they resend without recognizing its contextual and historical implications (Love, 2017).

Online activity, and the confirmation bias that often accompanies it, can expand to more extreme enactments. Oren Segal, Vice President of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) Center on Extremism (cited in Jewish Telegraphic Agency & Sales, 2020), notes, “It starts with reading a narrative or posting material on a poll, and maybe that leads to joining a march and more. And we must remember that these are fundamentally narratives that inform violent extremist movements” (para. 6). In Charlottesville, Virginia, protesters chanted “Jews will not replace us” (Green, 2017, para. 2), and the mass murderer of worshippers at the Tree of Life synagogue was overheard telling Pittsburgh police that “all these Jews need to die” (cited in Timsit, 2018, October 27, para. 6).

These incidents are related to a recent study by Anti-Defamation League (2020) which reports that, in 2019, there were 2,713 pieces of what the organization labels propaganda was distributed in the U.S. by white supremacist groups, more than double the that reported during the previous year (1,214 incidences of propaganda), concentrated mostly in California, Texas, and New York. One example of the 2,173 is a flier that reads “Holocaust=fake news” (cited in Jewish Telegraphic Agency & Sales, 2020, para. 3).

Distorting the Holocaust in ‘Secondhand Memory’

These intentionally distorted histories and ethno-centrist narratives are at the core of the conspiracy-driven actions of January 6, and multiple related activities and events of recent years. These events coincide with continually rising visibility for alt-right groups and actors, continually increasing examples of violent acts perpetrated by alt-right and ethno-nationalist proponents and increasing authoritarian shifts toward nationalist government representations across the globe. These events further illustrate how the re-creation of historical narratives and cultural memory can re-direct understandings of hate and Othering, particularly in the case of Holocaust distortion and denial.

In the nearly eighty years since the Holocaust and WWII, maintaining factual historical has never been more crucial. For the last living witnesses, those women and men who were in their youth and young adulthood during the 1930s and 1940s, this might be the last anniversary they will be present to commemorate. By the time the 80th anniversary of the end of WWII arrives, it is likely that what historian Adelaide Assmann (2006) calls “communicative memory” or “the direct oral tradition between generations” will be “coming to an end, to be replaced by the secondhand memory of textbooks and documents. Memory is about to enter its ‘cultural phase’” (p. 6). This “secondhand” memory” could be, as Ricoeur (2004) argues, subject to “the abuses of a memory manipulated by ideology” (p. 68).

Central to the ideological manipulation of memory, both distant and recent, is a phenomenon widely labeled by the right as “fake news.” Several critical incidents listed below have targeted “Othered” non-Christian religion and spiritual traditions. Scholars and political voices also raise concerns about the potential impact of Holocaust denial when amplified by alt-right media (Lengel, Newsom & Yeung, 2020). Communication scholar Aaron Delwiche (cited in Gstalter, 2018) notes antisemitic incidents are a reminder that this sort of rhetoric has consequences.

Holocaust Denial and Distortion Disguised as Nationalism

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) points out a rise of 60% in antisemitic incidences in the United States from 2016 to 2017, which coincided with the election of Donald Trump and the increase in Holocaust denial by labelling the Holocaust as “fake news” (Rubin, 2018). Examples include a December 2019 knife attack at a Rabbi’s home in Monsey, New York (Romero & Dienst, 2019). The ADL further notes “the rise in propaganda, however, comes alongside a 20 percent drop in events held by white supremacists, to 76 from 95, according to the report. Most of the events were not publicized in advance, as groups opted for so-called ‘flash demonstrations’ in which protesters gathered quickly without notice” (Jewish Telegraphic Agency & Sales, 2020, para. 7).

The reclamation of the ethno-nationalist rhetoric has motivated extremist groups to action and extremist activity. The denial of historical facts has been a vehicle for ethno-nationalism to justify hate against groups who do not represent their agenda. As a result, counter and reclamation hate based rhetorical campaigns initiated and perpetuated by the ethno-nationalist agenda have functioned as an attempt to rewrite, redefine, and advertise false and baseless claims previously only existing in specialized groups and now being distributed to mainstream audiences.

Dorothy Kim (2017; 2018) argues the rise of white supremacism takes on a medieval, crusade-based form of ideology with an inherent antisemitism. The ties to ethnocentric histories and Holocaust denial and distortion express not only Whiteness, but Northern European racial purity. These approaches “whitewash” medieval Europe as aggressively as they seek to devalue non-European heritage (Fink, 2018). By choosing perceptual elements from both real and imagined histories, they can define their own traditions and versions of “truth”, rather than relying on specific historic data. Thus, ethno-nationalists build their interpretations of history around both unknown and known facts and focus on interpretive elements reinforcing their collective biases.

An additional strategy is the use of subtle, veiled, and/or coded language by neo-Nazi and white supremacists, such as the terms globalist and globalism which are “often associated with antisemitic conspiracy theories” (Stutman, 2019, para. 6). Additional examples include terms such as “anti-white” and “anti-American” on handbills printed from the Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi website that targeted Jewish elected representatives, including Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) in the midst of the 2018 Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court nomination hearings (Stutman, 2019, para. 8).

Deliberate Disinformation and Incorrect Misinformation

Disinformation and misinformation have complicated both Holocaust memory and modern political discourse. The complicity of social media in the Holocaust denial, distortion, and trivialization is significant (Bareither, 2020). There are many examples of antisemitic and Holocaust denial narratives promoted in social media, fanning across multiple platforms (Greenblatt, 2020; Oster, 2020). Social media user protection and free speech policies make blocking this form of hate activity problematic, and social media have been resistant to placing limits.

Especially prior to 2020, Facebook was accused of complicit behavior. Founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg acknowledged, but made light of, the fact that Facebook and other similar public forums have the potential of amplifying and perpetuating alternative face and false truths such as the denial of the Holocaust and genocides (Chappell, 2018). That changed in October 2020 when Zuckerberg announced a new Facebook policy prohibiting “any content that denies or distorts the Holocaust” (cited in Clayton, 2020, para. 1).

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reports Holocaust denial is more rampant than ever before, and even though the antisemitic nature of Holocaust denial is clear, social media outlets like Facebook have consistently refused to categorize Holocaust denial as a violation of its terms of service, or “Community Standards” (Anti-Defamation League, 2020). There are also arguments surrounding the complacency of Facebook in other events such as the efforts by Russia to influence voters and divide American society in the 2016 election in favor of Donald Trump.

The rise in “fake news” labeling of Holocaust narratives in social and right-biased media also influences an increase in antisemitic rhetoric and activities. The scope of dis- and misinformation has increased, the generation with first-person Holocaust survivors has dwindled, and the word ‘Holocaust’ has itself been mis-used metaphorically to identify other causes and genocides since the Second World War. In the process, a common understanding of the events of the Holocaust can become diluted, making alternative narratives in social and conservative media appear more legitimate (Ortiz, 2020; Pew, 2020; Reich, 2020). Deniers of the Holocaust and antisemitic messaging disseminated and perpetuated in public forums has led to an increase in hate-crime. For example, recent vandalization of Holocaust memorial sites and active shooter events at synagogue and religious sites have increased the visibility of the rising tone of antisemitic acts and criminal behavior.

As noted, scholars and political scientists have argued for years that Holocaust denial leads to a rise in antisemitic activity throughout Europe and the U.S. (Asfari & Hirschebein, 2018; Feingberg, 2020; Lobba, 2017; McElligott & Herf, 2017; Tye, 2020). Direct attacks on Holocaust sites and efforts include the vandalism of the New England Holocaust Memorial in Boston twice in 2017 (Hauser, 2017), the attack on Seattle’s Temple De Hirsch Sinai with antisemitic and Holocaust denial graffiti (KOMO staff, 2017), the posting of a Holocaust denial flier at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Beachwood, Ohio in July 2019 (Polansky, 2020), vandalism at the Nashville Holocaust Memorial and Santa Rosa Holocaust Memorial in June, 2020 merely two days apart. (Bandler, 2020).

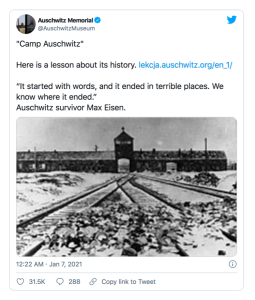

“CAMP AUSCHWITZ” and Holocaust Trivialization

A widely reported incidence of Holocaust trivialization occurred on January 6, 2021, in Washington, DC. Among the cell phone photos and videos of the riot was an image of a man wearing a dark hoodie that read “CAMP AUSCHWITZ” curved over an image of a skull and what appeared to be crossbones but may have been oars (Sales, 2021). Under the skull and oars, one third the size of “CAMP AUSCHWITZ,” read “Work brings freedom,” a rough translation of the German phrase “ARBEIT MACHT FREI,” a motto and iconic disinformation that Nazis used to mislead the newly arriving prisoners to concentration and death camps (Roth, 1980). This deceptive message of false hope remains written-in-steel on several camp entrances, including the large iron gate at the Auschwitz I concentration camp.

There was an extensive and expansive response to Robert Keith Packer, the shirt-wearer, who was identified and arrested one week after the January 6 riot. Numerous U.S. and international media organizations (see Adkins & Burack, 2021; Hall, 2021; JTA & TOL, 2021; Sales, 2021) reported on Packer and the many outraged reactions to the sweatshirt (Devine & Bronstein, 2021).

It may be that outrage in response to this image increased awareness of Auschwitz and its history. The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Memorial responded on its Twitter feed with “’Camp Auschwitz: Here is a lesson about its history,” and a link to extensive educational resources on Auschwitz developed by the Research Centre of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum (Lachendro & Setkiewicz, n.d.), followed by the words of Auschwitz survivor Max Eisen: “It started with words, and it ended in terrible place. We know there it ended.”

Image 2: January 7, 2021 Tweet from Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Memorial

Long Description

Auschwitz

Here is a lesson about its history. “It started with words, and it ended in terrible places. We know where it ended.” Auschwitz survivor Max Eisen.

An outcome of this “Camp Auschwitz” incident may be increased awareness about Auschwitz-Birkenau and, more broadly, the Holocaust. However, as memory of the Holocaust requires longer retrospection, there is a greater threat of disinformation campaigns and related problems of distortion and denial. In addition, political leaders denied or minimized the violence of January 6; Senator Ron Johnson (cited in CNN, 2021) dismissed those who stormed the Capitol as nonviolent “people that love this country,” and Trump himself suggested that rioters were “hugging and kissing” (cited in Stracqualursi, 2021, para. 1). Modern misinformation illustrates the dangerous potential of “alternative facts” to undermine collective memory and rewrite history.

The aftermath of the events of January 6, a riot that included hateful rhetoric and intentional displays of antisemitic symbolism (Dokoupil, 2021), will continue to influence both the lives of the individuals involved and those who witnessed their televised actions. Law enforcement and the Department of Justice continue to investigate and arrest those involved, and they will be tried within the legal system. Even so, antisemitic white supremacists and their supporters, both among the public and among public officials and media pundits, may continue to use these events to highlight issues and narratives for their own empowerment.

The violence of January 6 provides a disturbing comparison with the violence and dehumanization of the Holocaust. Alt-right actors have presented a consistent “tendency to turn a blind eye on Holocaust negation and genocide in the name of a misguided concept of freedom of speech” (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Memorial, 2021, para. 17). This tendency is part of a larger pattern of historical, factual distortion that promotes ethno-nationalism and antisemitism. Distortion of historical facts directly challenges the collective memories of nations and individuals. We remember and cannot forget the full extent of World War II, the deadliest conflict in human history, during which more than 60 million people were killed, and the Holocaust, the most horrific, systematic, state-sponsored killing in human history.

References

Adkins, L.E., & Burack, E. (2021). Neo-Nazis, QAnon and Camp Auschwitz: A guide to the hate symbols and signs on display at the Capitol riots. Jewish Telegraphic Agency, January 7.

Anti-Defamation League. (2020). Facebook has a Holocaust denial problem. Anti-Defamation League, July 1.

Asfari, A., & Hirschbein, R. (2018). Two Semites confront anti-Semitism: On the varieties of anti-Semitic experience. In Peace, culture, and violence (pp. 106-125). Brill Rodopi.

Assmann, A. (2006). Memory, individual and collective. In R.E. Goodin & C. Tilly (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of contextual political analysis. Oxford handbooks online, Oxford University Press. Oxford Academic

Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Memorial. (2021). “Camp Auschwitz.” Tweet. January 9, 2021. Twitter

Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Memorial. (2021). Deniers in different countries. Oświęcim, Poland: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Memorial.

Bandler, A. (2020). Santa Rosa Holocaust Memorial fountain vandalized. Jewish Journal, June 17.

Bareither, C. (2021). Difficult heritage and digital media: “Selfie culture” and emotional practices at the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(1), 57-72.

Beiler, M., & Kiesler, J. (2018). “Lügenpresse! Lying press!” Is the press lying? A content analysis study of the bias of journalistic coverage about ‘Pegida’, the movement behind this accusation. In K. Otto & A. Koheler (Eds.), Trust in Media and Journalism, 155-179.

Chandler, A. (2015). The “Worst” German word of the year. The Atlantic, January 14.

Chappell, B. (2018). Zuckerberg looks to clear up stance on Facebook, fake news and the Holocaust. National Public Radio, July 19.

Clayton, J. (2020). Facebook bans Holocaust denial content. BBC News, October 12.

CNN. (2021). Sen. Ron Johnson’s remarks about Capitol insurrection. New Day (CNN), Aired March 15, 8:30-9:00a ET.

Daniels, J. (2018). The algorithmic rise of the “Alt-Right.” Contexts, 17(1), 60-65. Sage Journals

Devine, C., & Bronstein, S. (2021). Man in “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt during Capitol riot identified. CNN, January 10.

Dokoupil, T. (2021). Some of the pro-Trump rioters who stormed the Capitol this month were closing with anti-Semitic images and messages CBS This Morning, January 26, 2021.

Eberl, J.-M. (2019). Lying press: Three levels of perceived media bias and their relationship with political preferences. Communications, 44, 5–32.

Economist, The. (2016a). America’s alt-right learns to speak Nazi: “Lügenpresse.” The Economist, 421(9017), 44, November 24.

Economist, The. (2016b). Lügenpresse, a history The Economist, November 26.

Fink, J. (2018). “Fake news,” Donald Trump “MAGA” sign placed outside Texas Holocaust Memorial Museum. Newsweek, December 19. Retrieved from Newsweek

Gstalter, M. (2018). “Fake News #MAGA” sign placed outside of Holocaust museum in Texas. The Hill, December 19.

Green, E. (2017). Why the Charlottesville marchers were obsessed with Jews. The Atlantic, August 15. Retrieved from The Atlantic

Greenblatt, J. A. (2020). Facebook should ban Holocaust denial to mark 75th anniversary of Auschwitz liberation. USA Today, January 26. Retrieved from USA Today

Hall, L. (2021). Rioter wearing “Camp Auschwitz” hoodie arrested, report says. The Independent (UK), January 13.

Haller, A., & Holt, K. (2016). The populist communication paradox of PEGIDA: Between “lying press” and journalistic sources. Paper presented at the Preconference: “Populism in, by, and Against the Media” of the 66th annual ICA conference “Communicating with power,” Fukuoka, Japan, 9-13 June.

Haller, A., & Holt, K. (2019). Paradoxical populism: How PEGIDA relates to mainstream and alternative media. Information, Communication & Society, 22(12), 1665–1680.

Hauser, C. (2017). Holocaust memorial in Boston is vandalized for second time this summer. The New York Times, August 15.

Holt, K., & Haller, A. (2017). What does “Lügenpresse” mean? Expressions of media distrust on PEGIDA’s Facebook pages. Politik, 20(4).

Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), & Sales, B. (2020). “Holocaust = fake news”: White supremacist propaganda is on the rise across U.S., ADL says. Haaretz, February 12.

JTA & TOL staff (2021). Capitol rioter in ‘Camp Auschwitz’ sweatshirt said identified as Virginia man. The Times of Israel, January 11.

Kellner, D. (2017). Brexit plus, whitelash, and the ascendency of Donald J. Trump. Cultural Politics, 13(2), 135-149. Duke University Press

Kim, D. (2017). Teaching medieval studies in a time of white supremacy. In the Middle, August 28.

Kim, D. (2018). Medieval studies since Charlottesville. Inside Higher Ed, August 30.

Kirschbaum, E. (2015). Revived Nazi-era term “Luegenpresse” is German non-word of year. Reuters, January 13.

Koliska, M., & Assmann, K. (2019). Lügenpresse: The lying press and German journalists’ responses to a stigma. Journalism. Sage Journals

KOMO Staff. (2017). Temple De Hirsch Sinai vandalized with anti-Semitic graffiti. KOMO News, March 10.

Lachendro, J., & Setkiewicz, P. (n.d.). KL Auschwitz—Concentration and extermination camp (Trans., W. Zbirohowski-Kościa). Research Centre of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Eduexe

Lipstadt, D. (1993). Denying the Holocaust: The growing assault on truth and memory. Free Press.

Livingstone Smith, D. (2011). Less than human: Why we demean, enslave, and exterminate others. MacMillan.

Lobba, P. (2017). Testing the “uniqueness”: Denial of the Holocaust vs denial of other crimes before the European Court of Human Rights. In U. Belavusau & A. Gliszczynska-Grabias (Eds.), Law and memory: Towards legal governance of history (pp. 108-128). Cambridge University Press.

Long, A. (2002). Forgetting the Führer: The recent history of the Holocaust denial movement in Germany. Australian Journal of Politics & History, 48(1), 72-84.

Love, N.S. (2017). Back to the future: Trendy fascism, the Trump effect, and the alt-right. New Political Science, 39(2), 263-268. Taylor & Francis Online

McElligott, A., & Herf, J. (2017). Antisemitism before and since the Holocaust: Altered contexts and recent perspectives. In A. McElligott & J. Herf, (Eds.), Antisemitism before and since the Holocaust (pp. 1-19). Palgrave Macmillan.

Nesbitt, J. (2016). Donald Trump supporters are using a Nazi word to attack journalists. Time, October 25.

Newsom, V.A., Lengel, L., & Yeung, M.F. (2020). Alt-right masculinities: Construction and commodification of the ethnonationalist anti-hero. Women & Language, 43(2), 253-287.

Noack, R. (2016). The ugly history of “Lügenpresse,” a Nazi slur shouted at a Trump rally. The Washington Post, October 24.

Ochab, E.U. (2020). Why challenging Holocaust denial and distortion matters. Forbes, January 27.

Ortiz, J.L. (2020). As world marks International Holocaust Remembrance Day, anti-Semitic attacks are on the rise. USA Today, January 27.

Oster, M. (2020). TikTok social media platform users target young people with anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial, study finds. Cleveland Jewish News, June 22.

Pew Research Center. (2020). What Americans know about the Holocaust. Religion and Public Life, January 22. Pew Research Center

Polansky, R. (2020). 3News investigates: Rise in anti-Semitic incidents goes beyond NYC attacks. WKYC News, February 21.

Polgar, M. F. (2019). Holocaust and human rights education: Good choices and sociological perspectives (First edition). Emerald Publishing.

Popper, I. (1848/1849). Zwischen mir und mein Volk soll sich kein Blatt Papier drängen! Lithographie, 355 x 336 mm. Satyrische Zeitbilder (28). Herzog August Bibliothek Signatur Graph. C: 223. Wikimedia Commons

Reich, W. (2020). Seventy-five years after Auschwitz, anti-Semitism is on the rise. The Atlantic, January 27.

Ricoeur, P. (2002). Memory, history and forgetting. The University of Chicago Press.

Roth, J.K. (1980). Holocaust business: Some reflections on arbeit macht frei. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 450(1), 68–82. JSTOR

Romero, D., & Dienst, J. (2019). Suspect pleads not guilty after five stabbed at Hanukkah party at rabbi’s home in New York. NBC News, December 28.

Rossoliński-Liebe, G. (2012). Debating, obfuscating and disciplining the Holocaust: Post-Soviet historical discourses on the OUN–UPA and other nationalist movements. East European Jewish Affairs, 42(3), 199–241.

Rubin, J. (2018). American anti-Semitism: It’s getting worse. Washington Post, October 27.

Sales, B. (2021). Rioter in ‘Camp Auschwitz’ sweatshirt identified as Virginia man. Cleveland Jewish News, January 10.

Shafir, M. (2002). Between denial and “comparative trivialization”: Holocaust negationism in post-communist East Central Europe. Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism, 19(2), 1-77.

Shermer, M., & Grobman, A. (2000). Denying history: Who says the Holocaust never happened and why do they say it? University of California Press.

Southern Poverty Law Center. (n.d.). Andrew Anglin.

Southern Poverty Law Center. (2019). Holocaust denial.

Stracqualursi, V. (2021). Trump lies about Capitol riot by claiming his supporters were ‘hugging and kissing’ cops. CNN Politics, March 26.

Stutman, G. (2019). White supremacist recruitment flyers found at UC Davis. JWeekly, September 25.

Timsit, A. (2018). The Pittsburgh shooting is the culmination of an increase in anti-Semitism in the US. Quartz, October 27.

Tye, L. (2020). When Senator Joe McCarthy defended Nazis. Smithsonian Magazine, July.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). (2016). Holocaust denial, explained. USHMM Holocaust Encyclopedia. Youtube

United State Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) (n.d.). Dachau. USHMM Holocaust Encyclopedia

Woeste, V.S. (2017). The anti-Semitic origins of the war on “fake news.” Washington Post, September 5.

“Fake News” comprises “purposefully crafted, sensational, emotionally charged, misleading or totally fabricated information that mimics the form of mainstream news.” MIT Press

Holocaust trivialization is any comparison or analogy that is perceived to diminish the magnitude of the Holocaust… The Wiesel Commission defined trivialization as the abusive use of comparisons with the aim of minimizing the Holocaust and banalizing its atrocities. Wikipedia

"De-Judaization” of the Holocaust: Removing or minimizing discussion about Jewish or antisemitic persecution, while nationalizing a political discourse about Nazi atrocities. The Atlantic

(Lying or enemy press) Critique of mass media, news organizations, and print journalism that contradict or oppose a political agenda (in this case: Nazi policy and ideology). In Nazi use, this term became a stigmatizing propaganda slogan. It often referred to international (external) mass media and falsely presumed and promoted the idea that the press was dominated by Jewish interests. Wikipedia

A subset of propaganda... false information that is spread deliberately to deceive people. Wikipedia

Incorrect or misleading information. Social media and networking sites help the spread of misinformation, fake news, and propaganda. Wikipedia