Aftereffects

A Resilient Response to Genocide: Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village (Rwanda)

Phyllis K. Lerner and Yael Friedman

Part 1 Remembrance

After World War II and the Holocaust, the world pleaded “Never Again.” Almost 50 years later, the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi shocked the world’s complacency—again. These two unique atrocities demand critical examination to better understand the context of and recovery from mass violence. In today’s Rwanda, survivors and perpetrators live alongside each other, and they offer a remarkable example of resilience and rebuilding.

It’s too easy to misunderstand the African continent and people when images, words and history curriculum from the past are frequently biased. To garner a brief overview from the 1960s, review this piece of photo-journalism: Reflections on 1960, the Year of Africa.

Visit this article: Teaching African History and Cultures Across the Curriculum to get a broad overview of Africa across the curriculum.

In 1994, the world was stunned by news reports describing a genocide in Rwanda as the Hutu government planned, led, and implemented a systematic massacre of 800,000 to 1 million people over 100 days between April and July 1994. In diplomat Samantha Power’s haunting book, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (2013), she calls the Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda “the fastest, most efficient mass murder of the 20th century” (Power, p. 334).

Studying history responsibly means learning about life before, during, and after the genocide to better understand its context. Rwanda, a small landlocked country located in East Africa, has been home to several tribal groups for centuries, most notably the Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa. In the pre-colonial period, these groups lived in harmony. Prior to German (1884-1916) and Belgian colonization (post-World War I-1962), “Rwandans swore allegiance to the same monarch [a Tutsi king], had the same culture, the same language, Kinyarwanda, and lived together on the same territory” (McDougall, p. 5). Occupied in 1884, it was one of the last African countries to be colonized (United Nations Rwanda: A Brief History of the Country, n.d.). Historically, Rwanda has been roughly 85% Hutu, 14% Tutsi, and 1% Twa: tribal groupings were determined by a caste system. Tutsis had access to more resources and traditionally herded cattle. Hutus farmed the fields. However, if a Hutu purchased 10 cows, they could then be considered Tutsi, an increase in social standing. Conversely, a Tutsi who lost family wealth might be viewed as Hutu.

In President Paul Kagame’s speech (2014) at the 20th Commemoration of the Genocide against the Tutsi, he shared, “All genocides begin with an ideology – a system of ideas that says: This group of people here, they are less than human and they deserve to be exterminated” (line 28). Following the growing eugenics movement, Belgian colonists believed Tutsis had physical characteristics more like those of Europeans. Due to their physiognomy and historic monarchy, Tutsis were granted more privileges by the Belgians than the Hutu were, even though the Tutsi were in the minority. In 1932, the Belgian colonial authority imposed identity cards, which classified individuals into fixed ethnic groups (United Nations Rwanda: A Brief History of the Country, n.d.).

In 1959, the Belgians switched their allegiance and supported a Hutu revolution, causing an estimated 300,000 Tutsis to flee the country. When the Belgians granted Rwanda full independence in 1962, a Hutu government was in power, inciting discrimination and waves of violence against the Tutsi. Tensions continued for decades with episodes of ethnic violence. Jean-Baptiste Munyankore (2007), a 60-year-old teacher, described the constant stress. “The massacres were unpredictable. That’s why, even when the situation seemed peaceful, both our eyes never slept at the same time” (Hatzfeld, para. 12).

In 1988, descendants of Tutsi refugees living in Uganda created the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). Their aims were for Hutus and Tutsis to share power in a reformed government and secure “repatriation of Rwandans in exile” (United Nations Rwanda: A Brief History of the Country, n.d.). The RPF launched a civil war in Rwanda in October 1990. In response, Hutu extremists blamed Rwandan Tutsis for supporting the RPF. Hutus began stockpiling weapons caches, allegedly receiving these supplies from European countries including France and Belgium, and training youth militia. They even compiled lists of Tutsis and moderate Hutus for assassination (Power, 2013, p. 343).

More information about Aegis Trust’s work in Kigali can be found on the website.

Hutu extremists also implemented an anti-Tutsi propaganda campaign. In December 1990, the Hutu newspaper, Kangura “Wake Up!” , had published the “Ten Commandments of the Hutu,” with content not unlike Hitler’s Nuremberg Laws in the 1930s. Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), a Hutu radio station, aired inflammatory and dehumanizing messages about Tutsis, including calling them inyenzi “cockroaches” and listing their addresses and license plates to pinpoint them (Power, 2013, p. 333).

Fighting continued until a cease-fire agreement, the Arusha Accords, was reached between the Hutu government and the RPF in August 1993. President Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu who served as Rwanda’s president from 1973 until 1994, signed the Arusha Accords. This pact declared to the international community that Rwanda was committed to peace, and to that end, a United Nations peacekeeping force was created. Commanded by French-Canadian Major General Roméo Dallaire, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) was stationed in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, together with RPF soldiers. Not only was this UN mission severely understaffed with only 2,500 troops, but General Dallaire received limited UN intelligence information. This had devastating consequences on his ability to coordinate a response once the genocide began (Power, 2013, p. 341).

Hutu extremists in Habyarimana’s government, who did not support the Arusha Accords, continued amassing weapons in preparation for renewed violence. World leaders dismissed the violent eruptions as internal conflict. On the evening of April 6, 1994, the plane on which Rwanda’s President Habyarimana and Burundi’s President Cyprien Ntaryamira were returning to Kigali was shot down by a missile. It remains unconfirmed who downed the plane: Hutu extremists argue it was the RPF and Tutsis argue it was Hutu extremists who wanted to escalate the violence against the Tutsis. The plane crash became a pretext to genocide.

Within hours of the plane crash, government soldiers and government-backed militias called interahamwe, “those who attack together” , set up roadblocks throughout the country to identify and kill Tutsis trying to flee. Hutus used the identity cards Belgians had introduced decades earlier to target Tutsis. The killers searched from house to house, massacring neighbors with simple tools: machetes, clubs with nails, knives, and other household objects. Additionally, they looted and burned homes, slaughtered cows and sheep, and inflicted widespread sexual violence against women and girls (Straus, 2016, p. 105). Many Tutsis fled to churches, believing they would be safe. But there was no refuge, save for with the few Hutus and non-Rwandans who were willing to hide Tutsis.

Witnesses and survivors recall bodies lining the streets, thrown in the rivers, subjected to weather and stray dogs. Rwandan survivor and author Celine Uwineza (2019) recalled the moment when, at ten years old, she realized her mother had been murdered by the interahamwe.

There was blood all over their [the interahamwe] bodies. Their traditional wooden weapons and machetes were covered in blood as well. ‘You kids,’ they said, ‘We will come for you tomorrow. We will kill you too. You are children of inyenzi and deserve to die like your parents’ (Uwineza, pp. 42-43).

To watch an interview with General Dallaire, select CLIP 8.

For more information about the United States’ position, please reference Samantha Power’s A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide.

When massacres started in Kigali, the RPF soldiers stationed there as a peacekeeping force began fighting again. Foreigners and expatriates were evacuated within days, and the UN peacekeeping force was reduced to 503 soldiers with few resources. General Dallaire quickly realized the killings constituted genocide, but he lacked the military power and authority to act against them. Over the next 100 days there was no notable international intervention. The genocide ended on July 4 when the RPF, led by General Paul Kagame, gained control of all Rwandan territories. With this defeat, over 2 million Hutus fled to neighboring Zaire, today’s Democratic Republic of Congo. Rwanda’s survivors never understood the abandonment by the UN and others in the international community. Teacher Innocent Rwilliza remembered the sense of neglect:

One day, in Nyamata, white armored cars arrived to collect the White priests. Out in the main street, the interahamwe thought these vehicles had come to punish them, and they fled, yelling to one another that the Whites were going to kill them. The armored cars never even stopped. … So, you can understand that a feeling of abandonment has found its way into the hearts of our survivors, and that it will never go away (Hatzfeld, 2007, para. 45).

The UN, after leaving Rwanda unprotected, claimed the perpetrators violated international humanitarian law. A UN International Criminal Tribunal (ICT) was established in 1995 to prosecute Rwandans accused of organizing, instigating, and perpetrating the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi and violating international humanitarian law. Before its closing in 2015, the ICT indicted 93 Rwandans on charges related to genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes (United Nations International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals, n.d.). Several alleged genocide orchestrators remain at large.

Rwanda is committed to remembering its history and bearing witness to the testimonies of survivors and perpetrators. In 2016, at the annual commemoration called Kwibuka, “to remember,” , Germany’s former Ambassador to Rwanda, Peter Fahrenholtz, said

If there is anything Germany can share from its own experience, it is this: facing up to the grim truth of what took place is the only path to begin reconciliation. A past that is not examined fully and honestly will remain a burden for the future (Fahrenholtz, lines 12-13).

Part 2 Respect

Following World War II, Israel welcomed an influx of orphans, primarily child survivors of concentration camps. Traumatized and vulnerable, the children were accommodated in special youth villages. The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda resulted in a similar crisis, leaving about one million orphans living on the streets or in child-led households (United Nations Supporting Survivors, n.d.). In response, the Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village was created to ensure “healing, education, and love, which empowers orphaned and vulnerable Rwandan youth to build lives of dignity and contribute to a better world.” (ASYV, Our Mission, n.d.)

Anne Elaine Heyman, founder of Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village, was born and raised in South Africa. She witnessed the terrible segregation of apartheid, which stayed with her when she and her family moved to America. Years later, Anne and her husband Seth Merrin attended a Rwandan lecture about the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. They were deeply moved when the speaker revealed a most significant concern—a relentless orphan crisis. With no way to care for the abundance of children, many were woefully left on their own. How does a nation recover from a genocide when so many young people have survived with trauma? Anne had spent time in Israel, where she was introduced to youth villages like Yemin Orde, which had cared for and educated concentration camp orphans. With respect for the child, the sites created a family environment of joy and security to promote healing, under the long-time leadership of Dr. Chaim Peri.

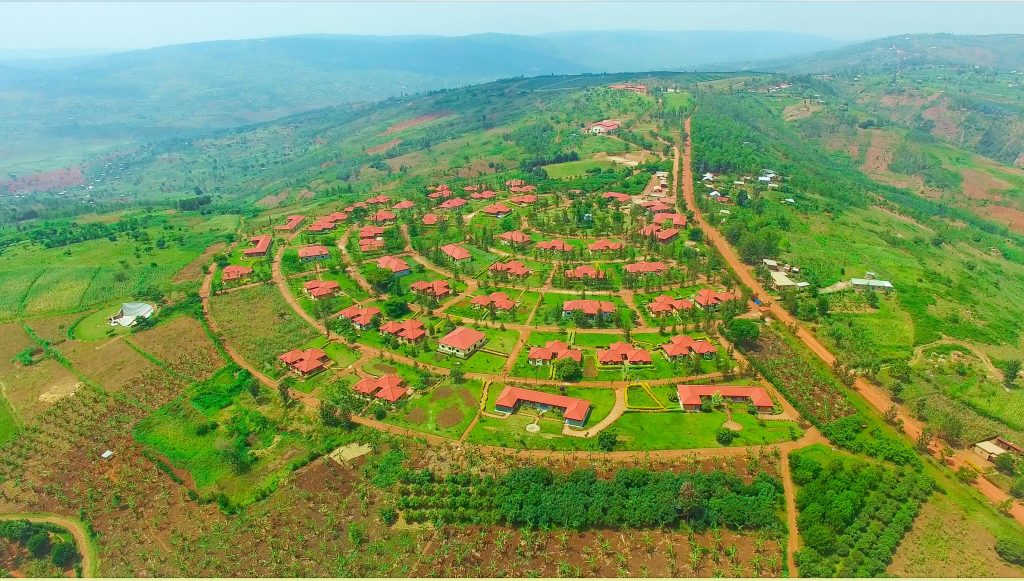

Anne’s vision was to adopt and adapt a “youth village” high school model in Rwanda and enroll genocide survivors while they were still under 18. To cultivate her ideas, Anne worked with Rwandan, American, and Israeli partners, including the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) and Yemin Orde Youth Village. Anne and her local team believed community engagement was important for success. In the Village center, a plaque at the Mango tree marks the spot where the team negotiated a fair price with 96 different landowners. Anne spent two years living in six-week cycles. First, time in Rwanda to connect with architects, builders, and psychologists, many of whom traveled with her to Israel’s Yemin Orde. Next in Israel, time was filled with analysis and discussions, designed to reframe the youth village with Rwandan culture and context. Then, back to Pennsylvania to fundraise and be with family. Finally, on December 15, 2008, the first 128 students moved in to make Agahozo-Shalom their new home. By 2011, they reached full capacity with 500 youth. In 2012, the first class graduated.

The Rwandan Project Coordinator and founding Executive Director, Sifa Nsengimana, said after study trips to Israel

The Yemin Orde philosophy in general is very compatible with the Rwandan tradition, the Rwandan culture, the Rwandan social life. And the most outstanding one is the idea of Tikkun Ha’lev” and Tikkun Olam,” of healing the self (heart) and healing the world and giving to community being part of a larger reality than oneself and that is something that will resonate with Rwandans (Reuters, 2007, 0:52).

These healing principles guide young people through trauma, first by living in a family unit, providing love, stability, sustenance, and health care. Once the students’ hearts have begun the healing process, they often develop a passion, take on leadership roles, and participate actively in the community. Additionally, repairing the world is a part of Village programming. By improving ASYV and local communities, the kids learn to be held accountable, build confidence, think critically, and find empowerment and joy serving others.

A Rwandan proverb Anne and Sifa often repeated is “If you see far, you will go far.” The notion is for students (usually referred to in the Village as kids) to look far across the horizon, see how big the world is and imagine countless possibilities. When the Village first opened for orphans in 2008, very few could see far. They knew Agahozo meant “a place where tears are dried”. They soon learned Shalom is Hebrew for hello, goodbye and peace. Agahozo-Shalom—a youth village of peace, where tears are dried. The staff welcomed

… a long line of teenagers, alone and shattered, (who) stood in the blazing sun holding paper bags containing all their possessions. Entire families of some had been wiped out, and they had no photographs. Some did not know their birthdays, or even what their real names were (Martin, 2014, para. 8).

There are several post-genocide schools, both public and private, for Rwanda’s most academic achievers. With intention, ASYV searches for at-risk teens. Recruited across all thirty districts, the students are nominated by the local Mayor, Government Minister, or School Principal. They are visited, interviewed, and selected by ASYV staff. The ASYV definition of vulnerability is drawn from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Bank, and Rwanda’s national policy which states, “A vulnerable child is a person under the age of 18 exposed to conditions which do not permit him/her to fulfil his/her fundamental rights for his/her harmonious development” (Ministry of Local Government, Information and Social Affairs, 2003).

ASYV does not consider the academic performance of potential recruits, as they recognize vulnerability and childhood trauma often hinder one’s school performance school. The kids (usually between 14-17 years) might have been silent in class, missed school to babysit siblings, or been labeled unmotivated. Most of the students are chosen because they reflect resilience—a spark—such as a passion around public speaking, playing sports, writing personal stories, or singing in church. Sixty percent are females, as Rwanda’s girls, like those of many other developing nations, are more at risk than their male counterparts. Just under half would not have been eligible for academic secondary school, had ASYV not intervened (ASYV, Finding Their Identity, Finding Their Home, 2019).

Many new students don’t know what’s ahead when they enter the gate. Some guardians want their kids to go because they needed fewer mouths to feed. Other families hope one successful youngster might ensure their future financial stability. The Village provides necessary items, from toothbrushes to sanitary pads, from notebooks to sport shoes, on site. The kids learn to use beds and linens, bathrooms with running water and toilets, hand washing stations, the routine of the dining hall’s three daily meals, and the benefits of a health clinic with social workers and a medical team. Student Jennifer Kabayiza Mbabazi said, “From the first time I entered the Village, I felt like … I now saw my future. The support we get from our family, from our leaders here – it’s not like in other schools” (ASYV, Beginning the Journey, 2019).

What the kids cherish immediately is becoming part of the family structure at ASYV. Mamas are the heart of the program and create a home for 20-24 adolescents. Most mamas have been with Agahozo-Shalom since the beginning. Many are genocide survivors, some lost entire families. The mamas are resilient, knowledgeable, and loving—and this job gives them a place and a purpose. An ASYV graduate serves as a family sibling, role model and intern. Cousins are English-speaking westerners (young career professionals) who work in special areas (hospitality, health clinic, English teaching, photography) for a fellowship year. From the first day of orientation, to the rituals that close their fourth year, the family is the center of healing and life lessons.

The cycle of Village life includes service in the kitchen, attending evening Family Time, performing at Friday night’s Village Time, going to school, and joining enrichment activities like clubs, sports and music. Friday Specials target learning opportunities beyond the academic curriculum, such as Life Skills, Career Development, Science Center, and Enrichment English. Add laundry and laughter, and the days and nights are quickly filled.

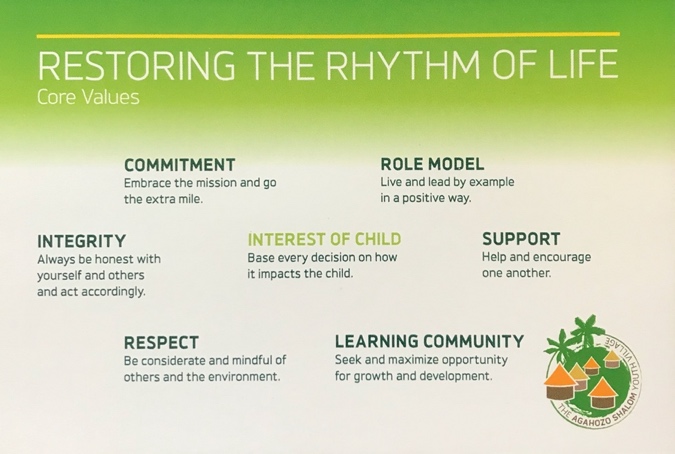

Sifa Nsengimana passed away suddenly, at 37, on November 23, 2012 in South Africa. Anne Elaine Heyman died in a horseback riding accident, at 52 years old, on January 31, 2014. Both women remain ASYV’s respected role models. Their core values, which are central ASYV pillars, have restored the rhythm of life for students and staff, who will forever pay it forward.

Long Description

The graphic is a diagram with seven words surrounding the phrase “Interest of child”. Click this text to see details below.

Title: Restoring the rhythm of life: Core values

In the center:

Interest of child: Base every decision on how it impacts the child.

Surrounding Interest of a child:

- Commitment: Embrace the mission and go the extra mile.

- Role model: Live and lead by example in a positive way.

- Support: Help and encourage one another.

- Learning Community: Seek and maximize opportunity for growth and development.

- Respect: Be considerate and mindful of others and the environment.

- Integrity: Always be honest with yourself and others and act accordingly.

Part 3 Resilience

One of the hardest characteristics to capture, and one of the most vital, is resilience. To heal at ASYV, to learn to build a self-reliant future, a vulnerable child must have the capacity for resilience. ASYV, too, must be resilient. We must be ready to stick by our kids through the challenges they will face at ASYV and in the world. (ASYV, Annual Report, 2019)

Ervin Staub was a Jewish Hungarian child during World War II. While many in his family, including his father, were killed in Auschwitz, he and his sister were taken into hiding by a Christian family. His astounding survivor story carried him towards a Ph.D. in psychology from Stanford followed by teaching clinical psychology at Harvard University. His focus? Good and evil. Why did the Holocaust happen, to people, by people? Dr. Staub’s research revealed four patterns, also evident in the Genocide Against the Tutsi. First, some people or “others” must be situated as separate and evil. Second, attitudes and antagonism can gradually become violent. Third, bystanders, outliers to good and evil, allow shifts to violence. Finally, in order to have resilience and healing, every side must gain deep understandings (Staub, 2020, pp. 3-5).

Following the Holocaust, the majority of Jewish survivors resettled in countries outside of Europe. They did not awaken daily to Nazi uniforms or German commands. However, Hutu and Tutsi neighbors returned to their homes, living side by side. Thousands of suspected murderers were arrested and placed in overcrowded local prisons. National courts tried as many as 10,000 defendants. From 2005-2010, gacaca courts, based on the “traditional community level grassroots judicial system”, were conducted within local districts to try other individuals suspected of crimes – from murder to stolen property – using the testimony of survivors and witnesses (Straus, 2016, p. 213). In 12,000 gacaca courts, approximately 1.2 million people were adjudicated to promote reconciliation. People painfully described their truths and provided killers the opportunity to confess their crimes and request forgiveness.

As of 2004, it became illegal for Rwandans to identify as Tutsi or Hutu. Reconciliation was meant to codify the Rwandan identity by nation rather than by tribe. Yet culture and government systems do not change quickly and certainly not overnight. Global activist and author of Manifesto for a Moral Revolution: Practices to Build a Better World (2020), Jacqueline Novogratz, who worked in Rwanda, wrote “the world needs brave people to create models of companies, organizations, schools, religious institutions, hospitals, prisons, and governments designed for a world interdependent” and the peoples’ spirits will be sustained by this challenge (p. 32). The challenge of being a resilient people and nation cannot just be managed by courts and settlements. Individual, family and community resilience are primary to Rwanda’s existence every day.

Rwanda’s resilience includes umuganda, a word that translates to “coming together in common purpose to achieve an outcome”. The Rwanda Governance Board designed this community service, based on a decades-old tradition, to rebuild the country (2017, p. 1). Reestablished in 2009, umuganda falls on the last Saturday morning of every month. Those aged 18-65, who are able, participate in local projects: environmental efforts include cleaning streets, cutting grass, and picking up litter; building and repair might improve roads and drainage ditches. A majority believe it “sheds light on a nation that has long been an example of how to recover from a devastating conflict with grace, hard work, and community involvement” (Bresler, 2019, para. 10).

Just as Rwanda’s policies and practices to promote reconciliation and resilience are crucial to its recovery, Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village must ensure the same for its at-risk youth. The opportunity to survive and thrive begins with ensuring life’s essentials; food, water, shelter, a family, health care, schooling, and a community of values, enrichment, and faith all form a child’s sense of security. The kids rise together for breakfast in the dining hall, attend school and numerous after-school activities. The Village enrichment program emphasizes the Core Values. Student Janvier Dushimimana was engaged in the Rwandan Culture course, which included drumming, dancing, public speaking and storytelling. “The curiosity of knowing where the dignity of Rwandans started inspired me to join the program. I have learned how we can still maintain our culture in this developing world” (ASYV, Healing the Heart, 2019). At night, they gather in a circle for Family Time, pondering life lessons that reflect resilience. As Mama Joy, at ASYV since 2010, shared, “I work hard on building a relationship with each child, and that allows me to know how to best support them” (ASYV, Healing the Heart, 2019). Former teacher and Director of Operations and Procurement Issa Sikubwabo describes Village success as

…healing, being healed, being empowered, and being a changemaker. Someone who will be impacted and will impact the community. For us we don’t want one who will maximize on the exam in the future become income addicted. This one, according to psychology, is not successful. We want someone who will succeed academically but also will have a great impact to the community. (B. Rosa, personal communication, April 29, 2016)

Umuganda is folded into ASYV’s concept of Tikkun Olam, repairing the world through service. Each Saturday morning, all kids are tasked with assignments. Some support the kitchen staff to harvest produce; others work on the farm cleaning up after animals or learning how to use agricultural tools; and everyone washes their clothes, homes, and communal spaces. On the last Saturday of the month, grade-level or special interest groups perform umuganda service in nearby Rubona. ASYV kids might make clay bricks for a new home or clear a drainage ditch to minimize flooding. Others teach local children English Language with games or work in the health clinic packaging pills for HIV patients. The kids learn how to give back to their communities by paying it forward at ASYV.

By their final year, the students’ spark is bright, giving them a meaningful sense of self and a resume of accomplishments. They typically excel academically and in a variety of enrichment activities. Yet one of the important things ASYV does for kids, instead of teaching them how to always be successful, is to teach them how to respond when they are not. Through Village life, they have proven they are resilient and talented, and possess the potential to build self-sufficient and fulfilling lives. They are ready for the future, and Rwanda and the world are ready for them.

Many ASYV students become global storytellers and advocates as they navigate and respond to life outside of the Village, including racial injustice and the Covid-19 pandemic. Liliane Pari Umuhoza was in the first class to enter and graduate from ASYV. Years later she continues to reflect the mission of the Village.

Each one of us has the power to take action. To the Black American community, I recognize your pain and I empathize with you. To the rest of the world, I urge you to STAND UP and SPEAK OUT! As Martin Luther King said, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ What are you doing to stop history from repeating itself? (Survivor’s Fund, 2020).

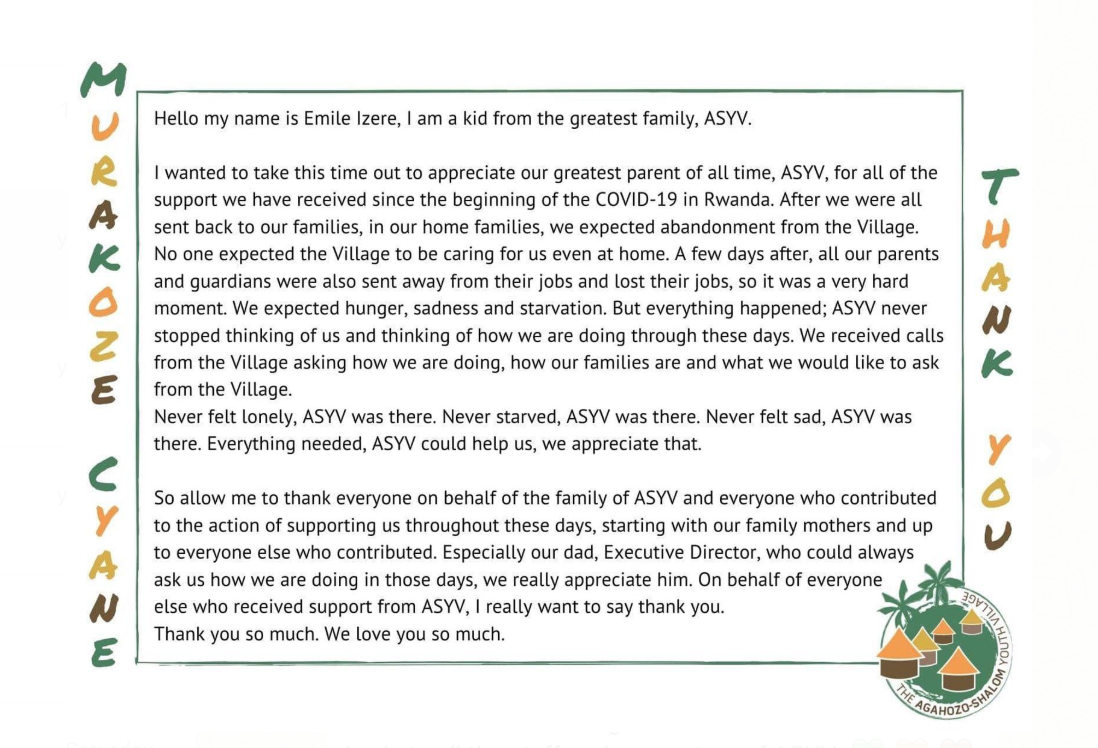

Student Emile I. explains how he managed enormous challenges and risks, while also offering gratitude (in the graphic) to the ASYV family.

Long Description

The image is a thank you note. Click this text to see details below.

Hello my name is Emile Izere, I am a kid from the greatest family, ASYV.

I wanted to take this time out to appreciate our greatest parent of all time, ASYV, for all of the support we have received since the beginning of the COVID-19 in Rwanda. After we were all sent back to our families, in our home families, we expected abandonment from the Village.

No one expected the Village to be caring for us even at home. A few days after, all our parents and guardians were also sent away from their jobs and lost their jobs, so it was a very hard moment. We expected hunger, sadness and starvation. But everything happened; ASYV never stopped thinking of us and thinking of how we are doing through these days. We received calls from the Village asking how we are doing, how our families are and what we would like to ask from the Village.

Never felt lonely, ASYV was there. Never starved, ASYV was there. Never felt sad, ASYV was there. Everything needed, ASYV could help us, we appreciate that.

So allow me to thank everyone on behalf of the family of ASYV and everyone who contributed to the action of supporting us throughout these days, starting with our family mothers and up to everyone else who contributed. Especially our dad, Executive Director, who could always ask us how we are doing in those days, we really appreciate him. On behalf of everyone else who received support from ASYV, I really want to say thank you.

Thank you so much. We love you so much.

References

Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village. (n.d.) Our mission

Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village. (2019). Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village 2019 annual report. Annual Report.

Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village. (2019). Beginning the journey. Annual Report.

Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village. (2019). Finding their identity, Finding their home. Annual Report.

Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village. (2019). Healing the heart. Annual Report.

Bresler, A. (2019, Feb.12). How Rwanda’s mandatory community workday made Kigali the cleanest city in Africa.

Fahrenholtz, P. (2016, Jan. 25). “Remarks by Germany’s Ambassador to Rwanda at Holocaust Remembrance Day.” Kigali Genocide Memorial.

Hatzfeld, J. (2007). Jean-Baptiste Munyankore. Life laid bare: The survivors in Rwanda speak. New York: Other Press.

Kagame, P. (2014). “Speech by H.E President Paul Kagame on 20th Commemoration of the Genocide against the Tutsi.”

Republika y’u Rwanda. View page here

Martin, D. (2014, Feb. 8). Anne Heyman, who rescued Rwandan orphans, dies at 52.

McDougall, G. (2011, Nov. 28). “Report of the independent expert on minority issues.” United Nations General Assembly: Human Rights Council Nineteenth Session.

Ministry of Local Government, Information and Social Affairs. (2003). National policy for orphans and other vulnerable children.

Novogratz, J. (2020). Manifesto for a moral revolution: Practices to build a better world. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Power, S. (2013). A Problem from hell: America and the age of genocide. New York: Basic Books.

Reuters. (2007, Feb. 1). ISRAEL: Youth village for orphans based on Israeli educational model is soon to be built in Rwanda.

Rwanda Governance (2017). Board Umuganda-2017.

Staub, E. (2020, January 16). This is how one man has spent his life studying the roots of good and evil.

Straus, S. (2016). Fundamentals of genocide and mass atrocity prevention. Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), Holocaust Encyclopedia

United Nations. “Rwanda: A brief history of the country.” Outreach Programme on the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda and the United Nations.

United Nations. “Supporting survivors.” Outreach Programme on the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda and the United Nations.

United Nations. “United Nations International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals.”

Uwineza, C. (2019). Untamed: Beyond freedom. Celine Uwineza.

“The major ethnic groups in Rwanda are the Hutu and the Tutsi, respectively accounting for more than four-fifths and about one-seventh of the total population. A third group, the Twa, constitutes less than 1 percent of the population. All three groups speak Rwanda (more properly, Kinyarwanda), suggesting that these groups have lived together for centuries.” Britannica

“Genocides have continued to happen since the Holocaust, for example in Rwanda in 1994. In 100 days, from April to July 1994, as many as one million people, mostly Tutsis, were massacred when a Hutu extremist-led government launched a plan to wipe out the country’s entire Tutsi minority and any others who opposed its policies.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Physiognomy, the study of the systematic correspondence of psychological characteristics to facial features or body structure. Because most efforts to specify such relationships have been discredited, physiognomy sometimes connotes pseudoscience or charlatanry. Physiognomy was regarded by those who cultivated it both as a mode of discriminating character by the outward appearance and as a method of divination from form and feature. Britannica

This 1993 agreement aimed to end the conflict between the Rwandan parties that comprises all the agreements achieved through the peace process as an integral part of it. The agreement establishes a Transitional Government and sets out a time frame for implementation. United Nations Peacemaker

The Interahamwe militia played a major role in the Rwandan genocide of 1994. Early in 1992, … political organizations affiliated with President Habyarimana formed two militias the Interahamwe ("Those Who Attack Together") and the Impuzamugambi ("Those Who Have the Same Goal"). They would play a central role in the atrocities that commanded the world's attention in 1994" (USIP Jan. 1995). UNHCR refworld

The ICTR was international in composition and was located in Arusha, Tanzania. The tribunal was not empowered to impose capital punishment; it could impose only terms of imprisonment. The governing statute of the ICTR defined war crimes broadly. Murder, torture, deportation, and enslavement were subject to prosecution, but the ICTR also stated that genocide included “subjecting a group of people to a subsistence diet, systematic expulsion from homes, and the reduction of essential medical services below minimum requirement.” Britannica

“On November 27, 1914, they founded the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC or "Joint"). Originally the result of a merger of two newly established relief committees, the largely Reformed American Jewish Relief Committee and the Orthodox Central Relief Committee, the JDC was joined by a third committee, the People's Relief Committee, composed of labor and socialist groups, in early 1915. The initial purpose of the Joint was to raise and distribute funds to help support the Jewish populations of eastern Europe and the near east during World War I.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Those accused of participating in the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda were primarily tried in one of three levels of court systems: the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), Rwandan national courts, or local gacaca courts. ‘Gacaca’ is derived from a word in Kinyarwanda (for grass) and refers to a traditional mechanism for resolving local disputes that has been revived and adapted to ascertain what occurred during the Rwandan genocide and bring its perpetrators to justice. Oxford Public International Law