Representations

Museums and Memorials: Never Again is Written in Stone

Avril Alba and Judy LaPietra

Introduction

On a winter’s day in 1995, on the fiftieth anniversary of its liberation, Renée Firestone fought back tears as she walked through the open remains of the former Nazi extermination camp known as Auschwitz-Birkenau. She recalled her experiences as a young woman in the camp some fifty years earlier:

If these wires, if these bricks could talk, the stories they could tell,

the suffering, and the starvation, and the beatings, and the

punishments… Well, I hope that the world will see it while it is still

here, because we are not going to be here much longer. And once we,

the survivors, are gone, I’m afraid the world will completely forget (Firestone, 2020).

The remains of the former camp exist today as a reminder of the barbarous history that unfolded there when Renée was a young inmate. Auschwitz-Birkenau served as ground zero for the execution of the so-called Final Solution to the Jewish question during the Nazi European onslaught of the Second World War. Over 1.1 million men, women, and children perished at this infamous site in southern Poland, among whom were the family of Renee Firestone. Today it remains as a prominent memorial in the landscape of Holocaust memory, the ruins of which have become both a testament to the past and a warning for the future.

Firestone’s testimony, delivered at the former Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, raises a number of questions as to the role and nature of these sites. The ‘If’ with which Firestone begins encapsulates both the promise and the limitation of the ruins. They remain, but only as silent witnesses to the crimes committed. In the current moment, as we experience the passing of the survivor generation, Firestone’s exhortation stands as a challenge for practitioners, scholars, and visitors to these sites. What are their potentialities, and equally, their limitations? Can they stand as a bulwark against forgetfulness? Or do they occlude rather than illuminate a brutal history? Can they aid in education about the past to build a better future? What kind of education is necessary for these sites to truly fulfill their role as bastions against the repetition of the human rights abuses?

Such questions apply to the multitude of Holocaust museums and monuments now existent across the globe. While many are not historical sites like Auschwitz-Birkenau, they often aspire to similar memorial goals and face similar challenges. To understand the contemporary dilemmas facing these institutions and the many and varied contributions they make to Holocaust commemoration and education, we need to understand their evolution, the communal and national contexts in which they undertake their work and the contemporary forms and directions they are taking.

Holocaust Memorials and Museums: A Short History

The earliest memorials to the Holocaust were planned and one even established, within the period of the Holocaust itself. In Majdanek, a Catholic Polish artist Albin Boniecki petitioned an SS Administrator to allow him to create a sculpture under the pretense that it would ‘beautify’ the camp. His “Three Eagles” was set upon a 2-metre column which concealed beneath it human ash. The symbolism of the eagle was interpreted by the Nazi guards as a National Socialist symbol but for the Polish prisoners, the eagle was a symbol of freedom. In other words, this monument was a subversive attempt to remember the martyrs while fooling the captors (see Marcuse 2010).

While not built until after the war, Polish Jewish sculptor, Nathan Rapoport developed the design for his Warsaw Ghetto Uprising monument during the period. Rapoport had fled to the USSR from Nazi-occupied Poland and upon hearing news of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising felt compelled to design and petition for a monument in honor of those who resisted. Similarly, many memorials built in the immediate post war period would focus on this and other acts of resistance. Other survivors, liberated in camps, created makeshift memorials on these very sites, often years before permanent memorials were enacted. The need to remember and mourn the dead was paramount (Young, 2000).

In the years to follow, state authorities and local actors in a variety of once Nazi-occupied countries, would begin to erect memorials. These memorials reflected not only the Holocaust past, but how that past connected to prevailing conceptions of national identity. Distinct differences in terms of ‘who’ and ‘what’ was remembered at these sites was evidenced in countries that were part of the former USSR and those in West/Central Europe. For example, in Buchenwald, a site run by Soviet authorities in the immediate aftermath of the war, a plan for a ‘hall of international community’ to commemorate 36 different national groups imprisoned at the site was developed. Other proposals included a pyramid symbolizing prisoner badges, to be inscribed with the words “In memory of the dead victims of fascism, as a warning for us and the world”. Here the emphasis was on the national and the communal, and the war, including the Holocaust, was largely characterized as the “fight against fascism” in Soviet memorialization initiatives (Marcuse, 2010).

By contrast, in the West, early memorials were mainly influenced by World War I memorials and emphasized the individual. Yet despite this focus, the particular nature of Jewish persecution under the Nazis was often subsumed into more generalized memorialization initiatives. For example, a proposed monument for the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising initiated during a rally on April 19 1944 in New York City (the first anniversary of the uprising) but not ultimately built until the 1980s (the Museum of Jewish Heritage) was constantly thwarted by objections that the designs were ‘too Jewish’ and would fuel antisemitism even in the aftermath of the war.

A ‘memory boom’ in the 1970s and 80s saw popular knowledge of the Holocaust increase through film and television depictions (Mintz, 2001). As a result, there was a rapid growth of a vast array of site specific and purpose-built Holocaust museums and memorials. They range from monumental examples such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington DC to small, local initiatives like Raoul Wallenberg Garden in Woollahra, Sydney. Each site embodies a particular approach to Holocaust memorialization, and often this approach changes and develops over time.

It is now difficult to think of a major city in Europe, North America or other western nation that does not have some kind of Holocaust memorial or museum. These sites testify to the international reach of Holocaust memory and its embodiment in memorial and museum forms. They also often relate to the histories of the places, communities and individuals in which they are built, and provide a backdrop for consideration of contemporary issues that these communities currently face. For example, the history of the Holocaust and of the Rwandan genocide are displayed together at the Johannesburg Holocaust and Genocide Centre. The history of Apartheid is also examined at South African Holocaust museums. What does such a coupling tell us about the contemporary relevance of the Holocaust in Africa today? (see Nates 2010)

The diverse nature of Holocaust sites around the world today raises questions as to how Holocaust memory is shaped at these locations. The continued increase and geographical spread of Holocaust museums in the present impels us to ask about the form and purpose of these sites. At the heart of such questions is the understanding that the Holocaust is not singularly defined at these sites, but rather it derives meaning from the time and place in which it exists. The following three examples of Holocaust memorialization illustrate this diversity of form and representation.

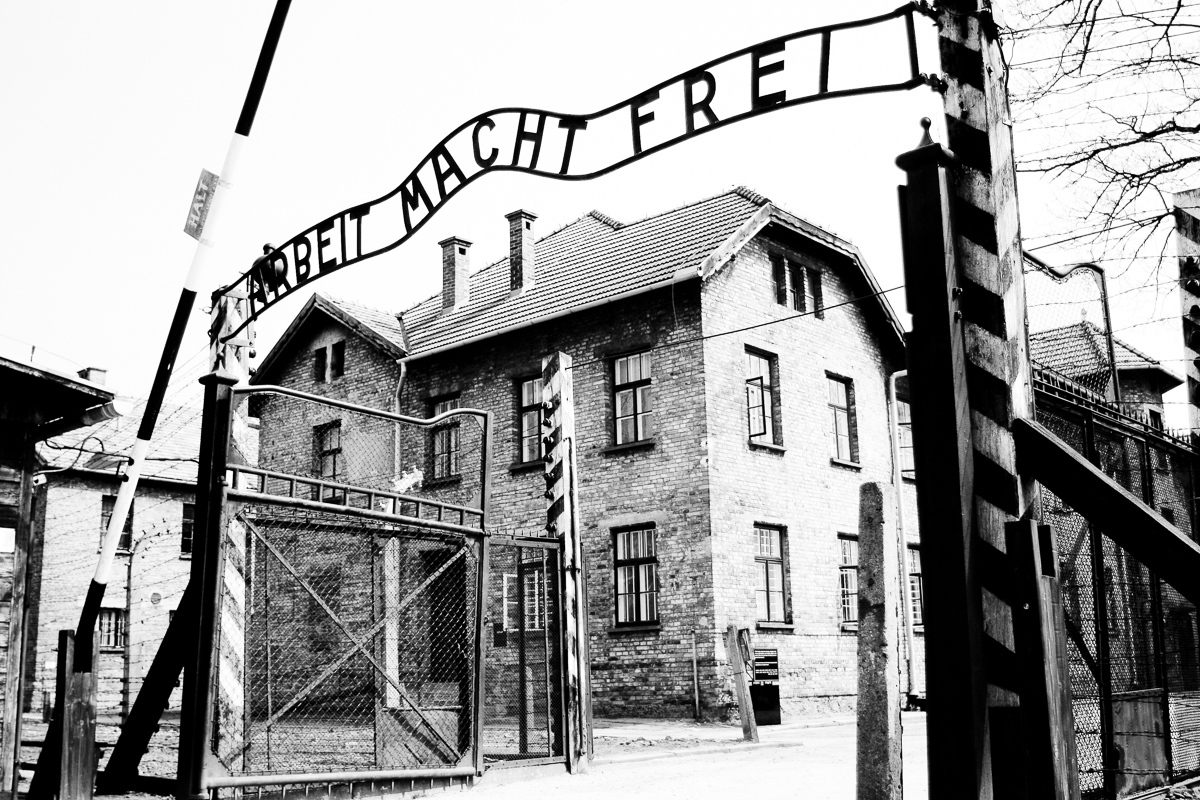

The Ruins of the Past as Memorial Sites: Auschwitz-Birkenau

Some of the earliest memorial sites to the Holocaust were the ruins of the extermination camps where so many perished at the hands of the Nazi’s during the war. The town of Oświęcim, Poland, or Auschwitz in German, is known for its role in the systematic extermination of European Jews and many others. As the largest of the Nazi extermination sites, the history of the Auschwitz site unfolded in stages, from early operations in May 1940 to its liberation by the Soviet Army in January 1945. During this time approximately 1.1 million victims perished in the Auschwitz camp system (Auschwitz 2021). The need to document the crimes at Auschwitz began in 1947 with the remains of the camp to be “forever preserved as a memorial” to Nazi depravity (Young, 1993). Today what remains are the modified remnants of the former camp, at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. The evolution of Auschwitz as a memorial site and its continued preservation prompts questions as to why there remains a need to memorialize such a place.

As liberating Soviet troops receded from Auschwitz in late 1945, the unprecedented human tragedy of what was carried out there during Nazi occupation necessitated recognition. The subsequent evolution of the Museum and Memorial over time have reflected the changing nature of what historian Pierre Nora refers to as “the will to remember” (Young, 2001). This will reflected in both national identity and location informed the ever-changing narrative of this Memorial.

The post-war Eastern European political landscape included Auschwitz, not as the defining symbol of the Holocaust, but as a symbol of fascist aggression where a perceived ongoing threat by West Germany was countered by the protection of the Soviet Union (Cole, 1999). Due to its location east of the Iron Curtain, Poles were placed at the center of memorialization at Auschwitz I during the early post-war years. Jewish victimhood, particularly at Birkenau, was largely marginalized as Auschwitz I alone was initially slated to represent a permanent exhibit. In fulfilling its stated mandate, it was thus fitting to have the “Monument to the Martyrdom of the Polish People” be reflected at Auschwitz I which underscored Polish victimhood at the hands of Nazi perpetrators. The mass murder of European Jews that occurred at Birkenau was relegated to a secondary position in Poland’s post-war narrative.

A 1957 international competition to create a monument at Birkenau amidst camp relics resulted in proposals for sculpture and architecture that would never come to fruition. At the core of this effort at memorialization was the conundrum of whose memory is represented at Auschwitz. Early unifying memorialization efforts proved futile due to an absence of common memory. It would largely become the contestation of Jewish and Polish narratives that would define the early years of the Memorial.

Competing Jewish and Polish ownership of the Auschwitz site continued after the fall of communism and was evident when, at the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation of the camp, former Jewish victims such as Renée Firestone were forced to facilitate a separate Jewish commemoration at Birkenau in response to then Polish President Lech Walesa’s exclusive commemoration of Polish victims without mention of Jewish victims of Auschwitz. Further revisions were made in 1996 with the creation of a Master Plan conceived by the Auschwitz Proposal Review Committee which included Polish government officials as well as leaders from international organizations such as Yad Vashem, the Anti-Defamation League, and the World Jewish Congress (Dwork, 2008). With the reorganization of the Museum and Memorial to include agreed upon principles of memorialization, the site was again transformed according to evolving political realities (Young, 2000).

The Auschwitz Museum and Memorial reminds us that, like all memorials, its meaning is ephemeral in that future generations will derive new meanings and understandings at this historic marker. Does this shift in the kind of memory constructed at Auschwitz today have consequences in the significance of our historical understanding? Can historical consciousness and remembrance be achieved at such sites of destruction over time in a way that does not trivialize the ‘experience’ of such a place given the fact that we cannot separate the site from its public life? With the recognition that such memorials depend upon the ever-changing public memory of the present, perhaps the Auschwitz site does contain an element that can be fixed over time, that cannot be altered by the numbers of visitors; that of the sacredness of the place of the deceased.

Working through the Past: Holocaust Memorials in German National Memory

German memorials possess a unique perspective and responsibility with regard to the Holocaust past. As James Young surmised, “How would a nation of former perpetrators mourn its victims” (Young, 2002)? The evolution of such memorials in a now-united Germany bears witness to this responsibility.

The answers to Young’s question are, of course, manifold. While still a divided country, Holocaust memorials and museums largely followed the ideological lines of East and West. The late 1980s saw a reckoning with the past that resulted in a Historikerstreit (History wars), about the nature of Nazi crimes and the demands of facing up to them, our how one might go about enacting Vergangenheitsbewältigung (German: coming to terms with the past ). Holocaust museums and memorials become part of this process of national accounting.

A distinctive form of memorialization developed largely in Germany were ‘counter memorials’. These memorials employed unconventional aesthetic forms that rejected the figurative in favour of the abstract, emphasizing ‘lack’ or ‘absence’ with regard to the memorialization of Germany’s Jews. They do not try to describe or reconstruct a place or event but rather attempt to evoke deep feeling and reflection. Examples range from famous, monumental void spaces such as Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum Berlin to the intimate Stolpersteine, (German: ’stumbling stones’) initiated by the German artist Gunter Demnig in 1992. These ten-centimetre square plaques are discretely placed amongst the street stones, commemorating the last place of work or residence of a victim of the Nazis.

Perhaps the most famous Holocaust memorial in Germany is the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, dedicated in Berlin in 2000. Originally a lay initiative headed by journalist Leah Rosh and World War II historian Eberhard Jäckjel, the project eventually became state sponsored and the final design only decided upon after two international design competitions and protracted public debate.

Some of the questions that animated public and scholarly discussion concerning the memorial included: Should the site only commemorate Jewish victims? Does Germany need a centralised memorial given the vast array of sites already in existence (both former camps and purpose-built sites)? Would the memorial simply have the effect of ‘burying’ memory and allowing Germany to assuage its guilt and hence relinquish responsibility for its past?

The design finally chosen, a vast field of ‘stelae’ designed by American architect Peter Eisenman (original design also by Richard Serra) did not put an end to such debates but rather marked their continuation, perhaps assuring those who thought this memorial might generate foreclosure comfort in that it continues to attract controversy and promote further debate on the resonance of the past in the present. Indeed, sites such as the Memorial to the Murdered Jews, have generated discussions concerning commemoration and compensation for an array of victims of National Socialism. Such sites now include a Memorial to the Sinti/Roma and to the victims of the T4 Euthanasia program.

Removed from the Past? Australian Holocaust Memorials

Our final example of Holocaust memorials and museums comes from perhaps an unexpected place, a country far removed from the crimes of National Socialism – Australia. Despite its geographical distance from the European theatres of war, in the post war period, Australia became home to the largest number of Holocaust survivors per capita after Israel and the survivors became central to Australian Holocaust commemoration.

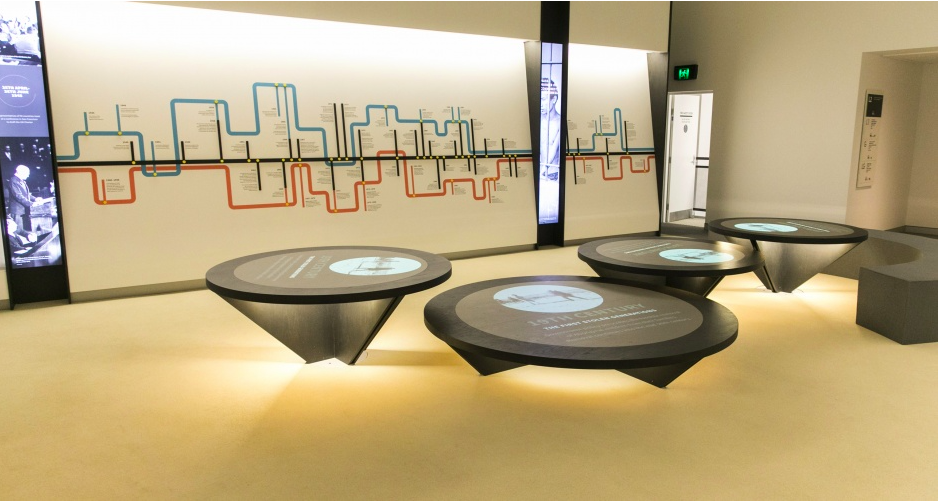

Indeed, Australia’s Holocaust memorial museums were founded and funded by Jewish survivors as centres for remembrance and research. This historical setting stands in sharp contrast to the majority of international sites, which are seldom solely Jewish in derivation; in fact, more often than not they are funded and run by state authorities. This meant that certainly in their first decades of functioning, the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne, opened in 1986 (see Cooke and Frieze, 2015) and the Sydney Jewish Museum, opened 1992, were conceived, funded and staffed largely by survivors (Alba, 2005).

This unusual situation meant that the majority of visitors to these museums, in their first iterations would be guided through the museum by a survivor. Thousands of student and general visitors had this unique experience for over three decades. The exhibitions also emphasised the Jewish experience from the perspective of those survivors active in these museums’ creation. In the last two decades, professional educators, descendants and other volunteers have now taken on these tasks, which has meant that the emphasis of the museums’ programs have greatly expanded (Alba, 2014). As well, major renovations and new exhibitions have taken place that have radically changed the nature of these once-particularistic exhibitions. This has resulted in the museums now also addressing topics such as colonial genocide, with reference to Australia’s own history, and the connection between the Holocaust and human rights with a focus on human rights issues currently facing the Australian community (Alba, 2016).

In this respect, Australian Holocaust museums reflect international trends in which we see many museums that began as centres for Holocaust commemoration and education move into related fields such as genocide prevention and human rights (see Blume and Rudling et al., 2014; Blumer, 2015; Chatterley, 2015; Moses, 2012). The influence of Holocaust memorialisation is clearly evidenced in museums commemorating genocide, peace museums, anti-slavery museums and centres for human rights and citizenship education (Dean, 2012).

Holocaust Museums and Memorials: The Future of the Past

Holocaust memorials and museums have emerged over some 80 years from places of immediate mourning and remembrance into international centres for commemoration, education and research. They have been fundamental in shaping national memories, as well as those of communities of interest and individuals both directly affected by the events of WWII and many far removed from these histories. Their prevalence and impact has led some scholars to argue that they have been instrumental in forging a global memory of the Holocaust, while others maintain this memory still retains a predominantly western focus (see Alexander, 2002; Levy and Sznaider, 2006; Rothberg, 2009).

One key question that faces museum professionals, scholars, researchers and visitors to these sites is how these places will continue to tell these histories in a fast-changing world. For some, this will mean investigating the Holocaust’s relevance to local histories, for others it will mean emphasising the Holocaust’s place in global struggles such as universal human rights. The only certainty is that despite being ‘set in stone’, it is the changing nature and meaning of these places that will remain their only constant feature. They will indeed tell stories, as Renée Firestone hoped they would. But what stories they will tell remains to be realized.

References

Alba, Avril. “Integrity and Relevance: Shaping Holocaust Memory at the Sydney Jewish Museum.” Judaism 54, no. 31–32 (2005): 108–15.

———. “Set in Stone? The Intergenerational and Institutional Transmission of Holocaust Memory.” In Remembering Genocide, edited by Nigel Eltringham and Pam Maclean, 92–111. Remembering the Modern World. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2014.

———. “Transmitting the Survivor’s Voice: Redeveloping the Sydney Jewish Museum.” Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust 30, no. 3 (September 1, 2016): 243–57.

Alexander, Jeffrey C. “On the Social Construction of Moral Universals: The `Holocaust’ from War Crime to Trauma Drama.” European Journal of Social Theory 5, no. 1 (2002): 5–85.

Ball, Karyn, and Per Anders Rudling. “The Underbelly of Canadian Multiculturalism: Holocaust Obfuscation and Envy in the Debate about the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.” Holocaust Studies 20, no. 3 (December 2014): 33–80.

Blumer, Nadine. “Expanding Museum Spaces: Networks of Difficult Knowledge at and Beyond the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.” Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 37, no. 2–3 (May 27, 2015): 125–46.

Chatterley, Catherine D. “Canada’s Struggle with Holocaust Memorialization: The War Museum Controversy, Ethnic Identity Politics, and the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.” Holocaust & Genocide Studies 29, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 189–211.

Cole, Tim. Selling the Holocaust: from Auschwitz to Schindler: How History Is Bought, Packaged, and Sold. Routledge, 2017.

Cooke, Steven, and Donna-Lee Frieze. The Interior of Our Memories: A History of Melbourne’s Jewish Holocaust Centre. Melbourne, Victoria: Hybrid Publishers, 2015.

Dean, David. “Telling Stories, Raising Awareness, Creating Opportunities for Change: Exhibition Proposals for the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 19, no. 4 (2013): 349–52.

Dwork, Deborah, and Pelt R J Van. Auschwitz. W.W. Norton, 2008.

Firestone, Renee (1994). Interview 151. Segment 46. Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation. Retrieved December 2020

Hamber, Brandon. “Conflict Museums, Nostalgia, and Dreaming of Never Again.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 18, no. 3 (2012): 268–81.

Kennedy, Rosanne, and Sulamith Graefenstein. “From the Transnational to the Intimate: Multidirectional Memory, the Holocaust and Colonial Violence in Australia and Beyond.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 32, no. 4 (December 1, 2019): 403–22.

Levy, Daniel, and Natan Sznaider. The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age. [English ed.]. Politics, History, and Social Change. Philadelphia, Pa: Temple University Press, 2006.

Marcuse, Harold. “Holocaust Memorials: The Emergence of a Genre.” American Historical Review 115 (February 2010): 53–89.

Mintz, Alan L. Popular Culture and the Shaping of Holocaust Memory in America. Samuel & Althea Stroum Lectures in Jewish Studies. Seattle, [Washington] ; University of Washington Press, 2001.

Moses, A Dirk. “The Canadian Museum for Human Rights: The ‘uniqueness of the Holocaust’ and the Question of Genocide.” Journal of Genocide Research 14, no. 2 (2012): 215–38.

Nates, Tali. “‘But, Apartheid Was Also Genocide … What about Our Suffering?’ Teaching the Holocaust in SouthAfrica – Opportunities and Challenges.” Intercultural Education 21, no. S1 (2010): S17–26.

Rothberg, Michael. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Cultural Memory in the Present. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2009.

“History.” History / Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Young, James E. “Germany’s Holocaust Memorial Problem—and Mine.” The Public Historian 24, no. 4 (2002): 65–80.

Young, James Edward. The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning. Yale Univ. Press, 2000.

Teaching Resources

Museums and Memorials: Never Again is Written in Stone

Click to view Teaching Resources for “Museums and Memorials: Never Again is Written in Stone”

Museums and Memorials: Never Again is Written in Stone

Students: please read and respond to this chapter from a free OER textbook on the Holocaust. Please write a short essay (parameters noted by the teacher); follow the three-topic writing prompts below. Please use academic writing style in your essays.

Alba and Lapietra (2023) examine museums and memorials around the world.

- How did memorials reflect post-war national identity?

- How do the authors describe a ‘memory boom’ starting in the 1970s?

- How are German and Australian museums serving different purposes?

- To explore more terms, students can use this online glossary

- Here is how to cite and reference our online textbook.

Teaching resource by Professor Michael Polgar, May 2023.

The Auschwitz II camp (also known as Auschwitz-Birkenau) included the most infamous killing center of the Holocaust. It's gate and rail terminals, like cattle cars and piles of remains, have become iconic images of Nazi crimes. The camp was fenced into ten sections, with sections and barracks therein for men, women, and two family camps, one for Roma. Prisoners were continually subject to horrifying conditions and abuses, including 'selection' for death (both on arrival and every day thereafter). Gas chambers and a growing number of crematoria were built and operated within this site, leading some to describe this or other death camps as killing factories. Murder was 'modernized' and industrialized with use of poison gas; handling of human remains was done by forced laborers. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

A Nazi code phrase referring to their systematic plan to murder every Jewish man, woman, and child in Europe. https://echoesandreflections.org/audio_glossary/

One of the six major Nazi death camps or killing centers. It “primarily served as a place to concentrate Jews from occupied-Poland whom the Germans spared temporarily for forced labor. It occasionally functioned as a killing site to murder victims who could not be killed at the Operation Reinhard killing centers, namely at Belzec, Sobibor, or Treblinka. The Majdanek camp also included a storage depot for property and valuables taken from the Jewish victims at the killing centers.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

1943 uprising by the Polish Home Army (commanded by Polish government in exile) with ~60K Polish fighters. The Red Army was approaching but stopped; the uprising was defeated on 10/2/43 by larger numbers of German fighters. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

One of the largest concentration camps established within Germany in 1937. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The Stolpersteine or Stumbling Stone (German) project commemorates those who were persecuted by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945. Wikipedia