Representations

Arts of Disruption

Ron Weisberger and Howard Tinberg

Arts of Disruption: A Deep Reading of Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” and Dan Pagis’s “Autobiography”

Abstract

The Holocaust is a complex subject. The facts are, of course, important and accessible: the date of Kristallnacht, for example, or the timing of the 1942 Wannsee Conference. But if history is in part a study of causation, the Holocaust invites a deep dive into examining long-term causes. Moreover, the study of the Holocaust in some ways disrupts our sense of the past, muddles clear lines of cause and effect. Perpetrators portray themselves as victims, and guilt is apportioned retrospectively and prospectively: before and after the event of the Holocaust itself. Adopting an interdisciplinary approach, as we intend to do in this chapter, both enriches our understanding of the Holocaust while at the same time challenges casual assumptions and previously learned beliefs. Moreover, the study of the Holocaust in some ways disrupts our sense of the past and muddles clear lines of cause and effect. Perpetrators portray themselves as victims, and guilt is apportioned retrospectively and prospectively: before and after the event of the Holocaust itself. Adopting an interdisciplinary approach, as we intend to do in this chapter, both enriches our understanding of the Holocaust while at the same time challenges casual assumptions and previously learned beliefs.

In this chapter, we intend to demonstrate the disruptive nature of Holocaust study by focusing on the work of Art Spiegelman and Dan Pagis. We will discuss Spiegelman’s graphic memoir, Maus, and a poem by Dan Pagis, “Autobiography.” We hope to give our readers- a roadmap with which to read thoughtfully these challenging works. For example, we share a reading exercise in which you are initially given a page from Maus for analysis, prompting you to think about how Spiegelman disrupts chronology to produce an ironic juxtaposition of past and present, showing how Spiegelman artfully breaks the wall between that which came before and that which is happening now. Similarly, when reading Dan Pagis’ poem, “Autobiography,” we hope to show you how poetry can disrupt our conventional expectation as to the uniqueness of the Holocaust in human history.

Introduction

We start with a paradox. The study of the Holocaust is a lesson in unlearning. We don’t mean that the Holocaust didn’t happen, quite the opposite. The evidence is overwhelming. As historians have shown us, over six million Jews (as part of the “Final Solution”) and countless others were murdered by the Nazi régime. Beginning with the Nuremberg Trials immediately after the war from 1946-1947, a vast amount of documentation was collected. Subsequently, historians such as Raul Hilberg, Yehuda Bauer, Saul Friedlander, Doris Bergen, and many others have researched and continue to do so in order to amplify the events and to illuminate how these crimes were carried out. In addition, we have the testimony of literally thousands of survivors and many perpetrators as well as those we would call bystanders, which add to the body of evidence attesting to the Holocaust’s effects on individuals and society.

Yet to truly at least begin to understand the Holocaust, we ask that you go beyond the facts–as important as they may be. We ask that you dig deeper. We have found that beyond the facts, it is the insights of the artists themselves that students like you have found most compelling. In this essay we highlight two important artists and their works and some of the ways we have used their work in the process of disrupting and unlearning previously held views about the Holocaust.

Maus: The Form Provides the Message

In our own course on the Holocaust, we have used Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning work, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. Spiegelman is what he calls a “comix” artist, producing comics for adult readers on provocative subjects, and was one of the innovators in the 1960s, making his mark first as an underground artist who would gain a mainstream following with the publication of Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. Maus is based on Spiegelman’s extensive interview with his father Vladek, who along with his mother, was a Holocaust survivor. At the same time, he bolstered the interviews with extensive research, including a visit to Auschwitz, the concentration camp where both his parents were imprisoned. We urge you to read both volumes of Maus before doing the exercises given in this chapter.

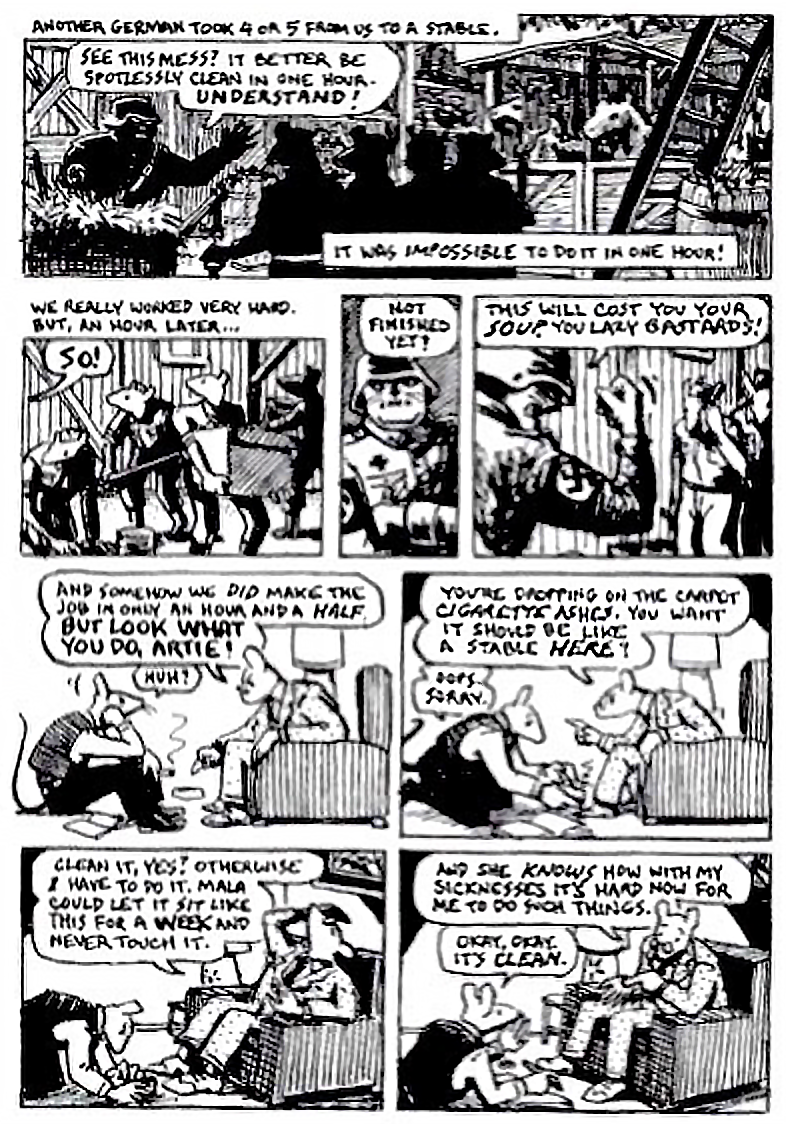

Maus can be read on several different levels. As a reader, you can gain what might be called a micro view of the periods before, during, and after the Holocaust as you read what happens to Vladek, his wife, Anja, and their family as they confront the rise of Nazism, the conquest of Poland and its effects on the Jewish population, life and death in the camps, and, finally, liberation. At the same time, events in the book occur in real time as Vladek’s son, Artie, interviews his dad and deals with Vladek, who can be very difficult. At this level, we see the effect of the Holocaust on the children of survivors, as well as the fraught relationship between a father and son. This all occurs in the form of a comic with Jews portrayed as mice, Germans as cats, etc. What can be startling but effective when read carefully is that each page contains a variety of panels that cross time periods. While a history teacher may balk at the interruption of the chronology, you will find it helps to gain a more nuanced understanding of the effects of the Holocaust on multiple generations. For example, in utilizing this graphic form, Spiegelman is able to demonstrate how historical events, like what Vladek experienced as a survivor of the Holocaust, affects his behavior in the present (see sample below). In reflecting on this work, consider some of the questions and insights that Maus raises for you.

Preparing to Read Deeply a Page from Maus

Spiegelman in Maus raises the question of whether someone such as Artie, or you yourself, can ever really understand the experience of those who were murdered in or who survived the Holocaust. As the Holocaust scholar Michael Bernard-Donals writes, Spiegelman attempts to balance “the telling of his father’s witnessing with his own account of witnessing, moving back and forth between what his father is telling of the past and his own perception of his father’s experience” (2006:168). Artie’s attempt to understand the Holocaust through his father’s experience is colored by his mother’s suicide when he was an adolescent, his perception that he couldn’t live up to the memory of his parents’ first son Richieu, who died during the Holocaust, and his ongoing struggles with his father’s eccentricities. His own experiences do not allow him to relate to his father’s struggles. In one set of panels, Artie says to his therapist: “No matter what I accomplish, it doesn’t seem much compared to surviving Auschwitz” (1991: 44). Who “owns” the story of the Holocaust as relayed in Maus? The father or the son? Or, to put it another way, what meaning should the survivor’s story have on the child of the survivor?

Reading a Page from Maus: An Exercise

In order to gain a deeper appreciation for Spiegelman’s method in Maus, read the page below carefully. We suggest reading it more than once. Then answer the questions that follow. We suggest writing these answers down and identifying which panels connect to your answers. We will follow with some reflections.

Approximately when do the events that are described on this page take place? How do you know?

Notice that all of the panels on the page have frames—with the exception of one. Which panel is that? What is happening there? Why does the artist not put a frame around that action?

Stepping back a bit, do you notice any difference in the content between the top and the bottom halves of the page? Be as precise as you can.

Looking again, do you notice any similarity in content between the top and bottom halves? Again, try to be precise.

Stepping back even further, try to speculate as to the artist’s intention and meaning here: why does he juxtapose the two halves of the page? Please explain fully.

Following up on the previous question: In reading this page (and Maus, generally) reflect on what you might have had to “unlearn” about how the story of the past is best told. To put it another way, when we try to capture in words what has happened in the past, is following chronology the only effective way to do so? Or might we follow a different order or logic? What might that be?

Reflecting after Reading “Maus”: An Unlearning

In this sample we see in graphic terms how the Jewish soldiers were treated by the Germans differently from the non-Jewish prisoners. This excerpt takes place immediately after the invasion of Poland in September 1939, but before the start of what is often considered the Holocaust. However, we can see Spiegelman foreshadowing what is to come. We also notice how Spiegelman can show abruptly but clearly the relationship between past and present. The sample makes the point that the barrier between the past and the present is porous, and the legacy of the Holocaust is palpable to those who experienced it, as well as those who inherit it. Vladek has not forgotten his treatment as a prisoner of war and relates it in some detail to his son; survivors often pull from their long-term memories very graphic details of their experiences. At the same time, as Spiegelman points out in this sample, it can have long-reaching effects on their behavior positively and negatively.

Another point reflected in this sample and throughout the work is that those individuals such as Vladek are more than victims. He is a complex person, who throughout his life, exhibits a great deal of ingenuity. This trait helps him, and in some ways his wife, to survive. In addition, towards the end of Maus, we see a photograph of Vladek in a crisp, new uniform worn by camp inmates (see below). As we point out elsewhere, “This photograph is startling in Vladek’s attempt to appropriate symbols of his suffering for ends other than what the perpetrators intended.” In this sense, Vladek appears to “assert some control over his past” (Tinberg and Weisberger 2014:72). It complicates our understanding of the term “victim.” We tend to see the victim as powerless in the face of the perpetrators, but here we see Vladek take charge of his life and use the tools of the oppressor (the camp uniform) for his own purposes. This is important because we don’t want to view those like Vladek who were caught up in the Holocaust simply as passive victims who were unwilling to resist. In fact, when possible, victims fought back as best they were able, sometimes in the form of an actual revolt, the most famous example being the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. At other times, resistance was a matter of preserving their religious beliefs and practices or recording for posterity what was occurring to them even if they themselves did not survive, as provided, famously, in the Oneg Shabbat archive.

Maus, like so many works dealing with the Holocaust, raises more questions than it answers. We would like you to consider, though, whether a work such as this–combining words and images and narrowing the broad scope of history to the story of one family–aides you in both the learning and unlearning process that we are discussing. By transporting you beyond the actual period of the Holocaust into the present and future, we want you to consider how such an approach both complicates but also enhances your understanding of this important subject.

We now turn to another genre—poetry– and one poet who, like Spiegelman, can disrupt prior assumptions in your journey from unlearning to learning.

Holocaust Poetry: Resisting Closure

Poets who choose the Holocaust as their subject often resist closure, leaving us to hang in mid-air and imparting in us an unsettling ambiguity. And, as we shall see, these poets may force us to reexamine previously held beliefs. We believe that poets who choose to write about the Holocaust face a uniquely difficult challenge: how does one put into words something so horrific, so traumatic, so incomprehensible, as the Holocaust?

Dan Pagis, whose work we will now analyze, was a survivor of the Holocaust and, thus, directly affected by the subject he is writing about. Born in Romania in 1930, Pagis, whose father emigrated to what was then called Palestine in 1934 and whose mother died during the war, was raised by his grandparents. In his teenage years, the younger Pagis spent three years in a Nazi camp. After the war, Pagis traveled to Palestine, where he was reunited with his father. Pagis would later settle in Jerusalem and obtain his PhD in Medieval Hebrew literature, becoming a well-known scholar in the field. Pagis was a prolific poet, as well: he began publishing his poetry at the age of 19, from there producing a half-dozen collections of poetry before his premature death at the age of 56. Noteworthy is the fact that Pagis wrote all his work—scholarly and poetic—in his adopted language of Hebrew rather than his mother-tongue of Romanian. The poem that we are about to read is translated from the Hebrew.

Reading Pagis’ “Autobiography”: An Exercise

Please read the Dan Pagis poem, “Autobiography,” below. We suggest that you copy and paste the poem, numbering each of the lines. We recommend that you read the poem aloud initially in order to allow the words to settle in your ear and in your mind. After the first read, please read the questions we have posed below. Then read the poem again, this time silently. After your second reading, please respond to these questions in writing.

When you have “talked back” to the poem, we would like you to read the poem a third time, highlighting any parts that remain confusing or difficult for you. Write down, if you can, the reason(s) for the difficulty. After this third reading, we will offer additional guidance and commentary about this challenging poem.

Autobiography

I died with the first blow and was buried

Among the rocks of the field.

The raven taught my parents

what to do with me.

If my family is famous

not a little of the credit goes to me.

My brother invented murder,

my parents invented grief,

I invented silence.

Afterwards the well-known events took place.

Our inventions were perfected. One thing led to another,

Orders were given. There were those who murdered in their own way

Grieved in their own way.

I won’t mention names

Out of consideration for the reader,

since at first the details horrify

Though finally they’re a bore:

you can die once, twice, even seven times,

but you can’t die a thousand times.

I can.

My underground cells reach everywhere.

When Cain began to multiple on the face of the earth,

I began to multiply in the belly of the earth,

and my strength has long been greater than his.

His legions desert him and go over to me,

And even this is only half a revenge.

- What does the title suggest to you? What associations does it create in your mind? What do you expect the poem to be about?

- To whom does the “I” refer, do you think? Should you assume that it refers to the author, Dan Pagis?

- In line three, there is a reference to a “raven.” Why the “raven”? What do you associate with that bird?

- In line five, what “family” is being referred to here? What clues are given in this stanza (paragraph) that might help you answer that question?

- In line ten, what “events” do you think are being referred to here? Why doesn’t the Speaker name those “events”?

- What are the implications of that word “Our” in line 11? What does the word imply?

- “orders were given” (12): Notice that the sentence is in what we call the “passive voice”—in other words, it is hard to see what the subject of the sentence might be. What are the implications of that fact?

- What does the speaker mean in line 17? If the details are about an event as serious as murder, how can they shift from being “horrific” to being a “bore”?

- In line 18, whom do you think is referred to by “you”?

- How can the Speaker’s death occur “a thousand times” (19)?

- “Cain began to multiply on the face of the earth” (22): How are the experiences and roles of Cain and the speaker different?

- Why only “half a revenge” (26)?

After the Third Reading: A Commentary on “Autobiography”

The title of this poem, “Autobiography,” would suggest the story of the writer’s life (and, in this case, death). It is important to point out, however, that the “I” of the poem need not be the poet, Dan Pagis. It is especially tempting given Pagis’ experience as a survivor of the Holocaust to read this and other Pagis poems on the subject as directly reflecting the poet’s own experience. Yet the “I” is properly seen as a fiction—something constructed by the poet for a particular meaning and purpose. Rather than referring to the “I” as the poet (who has constructed the whole poem), we will refer to the “I” as the Speaker.

The poem’s first stanza describes the Speaker’s death—at the hands of another. Note the seemingly detached tone the Speaker uses in describing his own demise. This “experience of displacement,” to use the term that the Hebrew literature scholar Robert Alter uses in discussing this poem and other poems by Pagis, is striking (1989; xii). In other words, the expected emotions prompted by shock and loss are displaced with a cool, almost nonchalant telling of one’s own death. Of course, the jarring fact that it is the murdered victim recounting these events (in contrast with the view that “dead men don’t tell tales) is jarring in and of itself. How can the dead speak?

We learn a bit more about the “family” affected by the murder: it is “famous” (5), but the Speaker names no names that would identify this “family.” Instead, we must read on before receiving a clue as to the Speaker’s identity: “My brother invented murder, /my parents invented grief” (7-8). Murder and grief have been with us throughout time, of course. In using the term “invented” to describe each, the Speaker takes us back to the beginning of recorded history—to the first murder and the first time the loss of a loved one was expressed. Before we go forward or backward in time, it is worth noting how unusual that term, “invented,” is in the context of murder. What does the term suggest for you? For us it suggests a machine or a technologically devised tool like the smart phone. Can murder be caused by such a tool? Of course a pistol or an AK47 would do the job or a mustard gas or cyanide or . . . . Depending on the device, murder can be perpetrated on a massive scale, as occurred during the Holocaust—through the use of Zyklon B in gas chambers and, before that, carbon monoxide from mobile vans.

If we retrace Biblically-recorded time, we return to the scene of the first murder—the killing of Abel by his brother Cain, as told in Genesis 4: 1-16 and in Peter Paul Rubens’ painting, “Cain Slays Abel,” reproduced below. The Speaker does not mention Cain by name (nor does the Speaker mention his mother Eve, nor his father Adam, nor even himself, Abel, by name). Yet we can infer, despite what Alter calls Pagis’ “brilliant obliquity” (xiii), the Speaker’s refusal to be direct and assume the deliberate choice to be oblique or indirect. We have the advantage that we have read other works by Dan Pagis which explicitly mention Cain and Abel (such as his “Brothers” or his very famous “Written in Pencil in a Sealed Railway Car,” in which Eve is given a voice). For Pagis, the story of the First Murder—a conflict of brother against brother resulting in death—is a lens through which he views the killing of millions of innocents during the Holocaust. Why does he do so? What are the implications of making that comparison between the First Murder of a brother by a brother and extermination of millions in mid-twentieth century? We hope to gain some answers as we read on in this poem.

The Speaker notes that, like all inventions, murder is capable of being “perfected” (11). In using that term, the Speaker points to a central irony: technological progress does not inevitably lead to a more just and civil society. Advanced machines may be put to the dastardly use of killing. The fact that the Holocaust was perpetrated by a German state known for its high culture (in music, the arts, literature) and technological achievements (well-paved autobahn and, of course, well-designed car engines) should not surprise us, the Speaker is saying. Zyklon B was an efficient, “perfected” killing tool.

In placing the Holocaust among the “well known events” (10) of murder throughout history—starting with Cain’s killing of Abel—the Speaker suggests that “What made has made of man” (to quote another poet, William Wordsworth, writing two centuries earlier) has occurred all too frequently and, perhaps, predictably (“Lines Written in Early Spring” 8). The Holocaust is not unique in that sense, demonstrating that tools for killing merely have been “perfected” over the centuries.

The Speaker’s reticence, in stanza four, to “mention names” (14), that is, to speak in detail about those who have lost their lives in genocides past and present (and who will, sadly, do so in the future) reflects the victim’s ambivalence about disclosing trauma: do I as a survivor-witness want to bring distress to and “horrify” my audience? What would be the point of that? Why should my suffering stand out from that of others, especially given the fact that the true witnesses are those who, in Primo Levi’s words, “saw the Gorgon,” that is, have breathed the killing gas or felt the perpetrator’s bullet piercing their skin (“Shame” 115)? The fear is that such details may overwhelm and then with repetition merely become a “bore.” In other words, the listener may experience “Holocaust fatigue” and become jaded even in the face of the most horrific violence, if referenced often enough.

For the witness of atrocity, every telling of that traumatic experience may bring its own death–a return to the scene of the crime—whether told “once, twice, or even seven times” (18). Despite the similarities between the Speaker’s experience and that of others who have followed him, one characteristic sets him apart from other victims of atrocity. As the first murder victim in recorded human history, the Speaker has a special burden: like the Ancient Mariner in another poem on atrocity and its consequences, the Speaker must tell his story throughout time (and he will “die a thousand times”). He and his brother are progenitors—forebearers—of all the victims and perpetrators that have existed and who will exist in the time to come. The Speaker’s influence as a result continues to “reach everywhere (21).”

After killing his brother, Cain would be punished with life rather than death. He would “multiply,” and his progeny would continue his line. Our Speaker would of course perish, and his descendants, the victims of atrocity, would “multiply in the belly of the earth (22).” Justice for the vast number of victims from Abel through the future seems all but impossible. Perhaps all that can be hoped for is “only half a revenge (26).”

Reflecting after Reading “Autobiography”: An Unlearning

As we note early in this chapter, reading the complex history and literature about the Holocaust “disrupts” many of the assumptions we have about the event and leads us to “unlearn” certain beliefs. For example, prior to reading about the Holocaust, you may have had the view that the Holocaust was a completely unique event in human history. Now, please do not misunderstand: the mass extermination of so many millions by the Nazis—a state-sponsored program of killing on an industrial scale—does in fact place the Nazi-run genocide in a special category. And by no means are we diminishing the extent and nature of this cruel campaign of atrocity. But in the poem “Autobiography,” the Speaker attempts to draw a clear line from the First Murder (Cain’s killing of Abel) to all the acts of murder committed over the panorama of history, including during the Holocaust. “Our inventions were perfected (11),” states the Speaker, meaning that while humanity became more efficient at killing, the precedent had already been set.

The implication that the Cain and Abel story predicted the Holocaust carries this disturbing lesson: that murder has at its root—its template, as it were: a violent act of brother against brother. It is tempting in studying the Holocaust to think of the perpetrators as monsters, capable of inhuman insensitivity and depravity. After all, their crimes were so brutal, so incomprehensible, as to make it exceedingly difficult to think otherwise. That would be a mistake, our author-survivors, Art Spiegelman and Dan Pagis, tell us. If we categorize these perpetrators as inhuman monsters, we relieve them and ourselves of the reckoning necessary to prevent such acts of cruelty in the future. In another poem by Dan Pagis, we are told

No no: they definitely were

Human beings: uniforms, boots.

How to explain? They were created

In the image (“Testimony” 1-4).

As Pagis affirms, if victim and perpetrators are “created/in the image” of God, then we face the troubling realization that any of us might be capable, in certain circumstances, of terrible acts of cruelty.

After Words: What We Hope You Take from This Lesson

We began this chapter with a warning and a paradox. We offered our view that in studying the Holocaust, you might very well find your prior assumptions about the subject disrupted and challenged. And we intimated that, as a result of this disruption, in learning about the Holocaust you likely would need to unlearn aspects that you had considered factual and replace them with new understandings.

For your convenience, we list here all that we hope you’ve taken from this chapter:

The realization that the Holocaust is a multi-dimensional subject which benefits from the use of many disciplines and many genres of representation—poetry, graphic or comic media, as examples of genres usefully studied here;

Recollecting the events of the Holocaust needs to be the work not only of the historians but the poets, artists, and researchers as well as survivors;

Reassembling the past requires not only an adherence to chronology (the facts and dates of events arranged in time), but also the work of memory;

Memory of trauma continues to influence survivors well after the fact: the past “bleeds” into the present;

Perpetrators of the Holocaust should not be denaturalized as monsters but rather seen as human beings who committed cruel atrocities against fellow human beings and whose behavior can be studied so as to enable us to identify and address similar behavior in the future;

The crime of the Holocaust itself is both distinctive and at the same time continuous with what has come before and, sadly, predictive of what might happen in the future;

Progress—advances in technology and culture—did not preclude or prevent an event like the Holocaust from happening, nor will it do so in the future.

References

Alter, R. (1989). “Introduction.” The selected poetry of Dan Pagis. Tr. S. Mitchell. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press.

Bauer, Y. (2003). Rethinking the Holocaust. New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press.

Bergen, D.L. (2016) War and Genocide: A concise History of the Genocide, 3rd. Edition. New York: Rowan and Littlefield.

Bernard-Donals. M. (2006) An Introduction to Holocaust Studies, Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson.

Coleridge, S.T. (1974). The rime of the ancient mariner. Poetical works. Ed. E. H. Coleridge. London: Oxford Univ. Press.

Friedlander, S. (2004). Nazi Germany and the Jews 1933-1845. New York: Harper-Perennial.

Hilberg, R. (2003). The Destruction of the Jews 3 vols. 3rd. Edition. New Haven, Ct. Yale University Press.

Langer, L. (1995). “Poetry.” Art from the ashes. Ed. L. Langer. New York: Oxford University 553-559

Pagis, D. (1989). “Autobiography.” The selected poetry of Dan Pagis. Tr. S. Mitchell. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. 5-6.

Rubens, P.R. (1608-1609). “Cain Slays Abel.” Accessed from Wikipedia Commons. 9 July 2020.

Spiegelman, Art. (1986, 1991) Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. Volumes I, II. New York: Pantheon Books.

Tinberg, H & Weisberger, R. (2014). Teaching, learning and the Holocaust: An integrative approach. Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press.

Wordsworth, W. (1975). “Lines written in early spring. Poetical Works. Ed. T. Hutchinson and E de Selincourt. London: Oxford Univ. Press.

The Holocaust was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its allies and collaborators. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Nazi pogroms against the Jewish population, including vandalism and destruction of businesses, synagogues, and homes (marked by broken glass). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

A Nazi code phrase referring to their systematic plan to murder every Jewish man, woman, and child in Europe. Echoes and Reflections Audio Glossary

"The war crimes trials of twenty-two major Nazi figures in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1945 & 1946 before the International Military Tribunal" Echoes And Reflections Glossary

"Someone who does something that is morally wrong or criminal." Echoes and Reflections Glossary

A person who speaks or acts in support of an individual or cause, particularly someone who intervenes on behalf of a person being attacked or bullied United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Comic books and comic strips, especially ones written for adults or of an underground or alternative nature Lexico

Located in German-occupied Poland, Auschwitz consisted of three camps including a killing center. The camps were opened over the course of nearly two years, 1940-1942. Auschwitz closed in January 1945 with its liberation by the Soviet army. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The freeing of concentration camp prisoners by Allied soldiers (or powers) in the final stages of the war (July 1944-May 1945). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

An advance hint of what is to come later in the story. Literary Devices

A highly poisonous insecticide which when exposed to air is converted into lethal gas. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Trucks reequipped as mobile gas chambers. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

... any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. United Nations