Settings

Exterminating Pests: Fireflies, Ladybugs and Children

Judith Brin Ingber

Abstract:

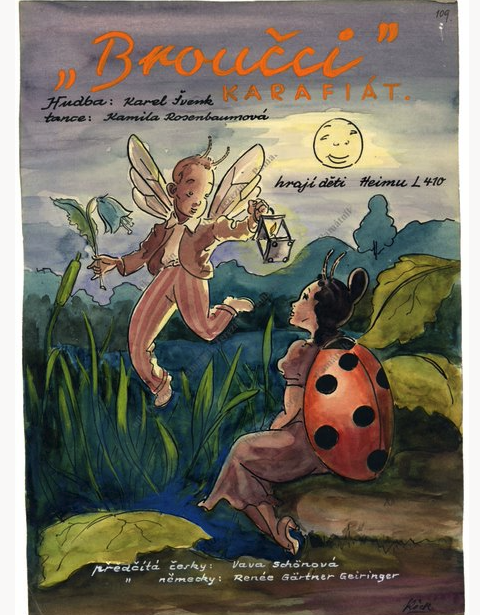

A special quartet of artists imprisoned in the Nazi ghetto camp Theresienstadt created a remarkable production called Broučci “Fireflies”. It was produced in 1943 and 1945, totaling 35 shows performed by casts of imprisoned children. It has been especially challenging to learn about the children, and about these four artists: Composer Karl Schvenk, Director Vava Shoenova, Set Designer/Costumer Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, and especially Choreographer Kamila Rosenbaumová, who had been famous in her own time. No photographs have been located of Broučci, nor any of the usual research materials for productions — no newspaper stories, dance reviews, essays in arts magazines, or information in Jewish archives. Two recent autobiographies, and an unexpected correspondence with the daughter of Kamila Rosenbaumová, were keys to understanding the choreographer’s pioneering work as the key creator responsible for Broučci.

The Unusual Story of Broučci or “Fireflies,” the Children’s Musical from The Ghetto Camp Theresienstadt, and its Choreographer Kamila Rosenbaumová

The city of Prague has had one of the longest and most important Jewish centers in East Central Europe. Jewish merchants in Prague markets are mentioned as early as 970 CE. The European military campaign of the First Crusade (meant to free Jerusalem from the Muslims) caused anti-Jewish riots in many communities, including Prague in 1096. In 1142 there was devastation when the synagogue and private homes were burned down. By 1270, the Jewish quarter on the Vltava river across from the royal castle was re-established, built around the synagogue known as the Altneuschul “Old-New Synagogue”. Today the Altneuschul is the oldest preserved synagogue in Europe.

In my own Czech American family, I grew up on stories of the magical Golem (no translation – Hebrew and Yiddish) created by the revered 16th century rabbi of the Altneuschul, Rabbi Judah Loew. His grave can still be visited in the old Prague Jewish cemetery near the synagogue. Rabbi Loew is remembered not only for his teachings, but for creating the legend of the powerful Golem, a creature fashioned from the mud of Prague’s Vltava River. Breathing life into the Golem, the esteemed rabbi emblazoned its forehead with the three letter Hebrew word for Truth. With a simple command, the rabbi could send the unstoppable Golem to rescue any Jew in peril. Stories of zealous priests kidnapping Jewish children for conversion featured Rabbi Loew sending the Golem to leap over high monastery walls and rescue the kidnapped children. Alas, the Golem couldn’t think for himself and another tale relates the time the rabbi’s wife asked her son to scrub the courtyard before the Sabbath. To save himself the work of bringing water from the Vltava, the son ordered the Golem to bring a pail of water. But nothing could stop the Golem from bringing pail after pail of water from the river, because the unworthy command was not the rabbi’s. The courtyard, the house, and the rabbi’s study all flooded. Rabbi Loew came running and, to stop the Golem, erased the first letter on the Golem’s forehead, the aleph. Instead of the Hebrew word for truth, with the first letter missing only two Hebrew letters remained (mem and tof) spelling the word for death. It was the end of the Golem. Ever after, generations have looked and looked for Rabbi Loew’s Golem. He never has turned up in any of the nooks and crannies of the Altneuschul, though Jews have hoped against hope that once again the Golem could rescue the Jews of Prague. Sadly, the Golem was not able to save the Jewish children of Prague from the Nazis.

By 1939, there were approximately 56,000 Jews living in Prague. Jewish communities from other areas of Czechoslovakia numbered around 356,000 and those in Slovakia included approximately 136,000. When the Nazis annexed what they called the Czech Protectorate on March 16, 1939, the dire situation for Czech Jews began. All the Jewish communities in the areas of Moravia, Bohemia, and Slovakia were centralized in Prague. They were forced to identify themselves by wearing the yellow star, and Nazi race laws were put in place expelling Jewish professionals from their jobs and children from schools. On September 27, 1941 the Nazis began deporting Jews to the fortress town Theresienstadt where they had set up the concentration camp known as Terezin. First to arrive were more than 45,500 Jews from Prague. The deportees were all crammed into Theresienstadt barracks, joined by Jews from Moravia, Bohemia, Slovakia, Austria, and Germany, with children separated from adults. From Theresienstadt Jews were deported to other concentration and extermination camps. By the end of World War II only 5,000 Jews returned from the camps to Prague. (Yad Vashem)

What Was Theresienstadt?

The usual tools for dance research include analyzing photographs, film, or video; studying newspaper reviews and essays in arts publications; interviewing artists and audience members; examining contemporary accounts of the performance in question. Research takes place in archives such as the Dance Division of the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center, the Archives of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, and the Dance Library of Israel in Tel Aviv. But in this case no photographs, articles, or reviews could be found, and none of the usual archives yielded any information about the Terezin musical productions or the artists who created them. It took me almost 50 years to get answers about who guided the children in Terezin to make art, persevering with extraordinary creativity despite imprisonment and death by the Nazis.

I first learned that Terezin was originally called Theresienstadt from the book, I Never Saw Another Butterfly. With its colorful drawings the volume could be mistaken for a picture book, but the poems and drawings by imprisoned children speak to an adult readership, describing the difficult life of the ghetto. Theresienstadt was originally a garrison founded in 1780 by Emperor Joseph II of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He named the army town after his mother, Maria Theresa, setting up army barracks, homes for soldiers’ families, and a little town square featuring a small outdoor stage. Taverns, a post office, bank, brewery, and soccer field were not far off, along with meadows, farmland, fruit trees and poplars. Twelve stone ramparts in the shape of a star enclosed Terezin. Train tracks could take passengers 30 miles to and from Prague, the capitol and biggest city of Czechoslovakia.

When the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia during World War II, they took over the army town of Terezin, transforming it into a ghetto and work camp they called Theresienstadt. After deportations from Prague began in Fall of 1941, the Nazis started deporting Jews from beyond the capitol. Some arrived wearing elegant resort clothing with evening gowns in their suitcases, having been misled into thinking they were traveling to one of Czechoslovakia’s famous spa towns. Upon arrival, however, it became clear Theresienstadt was a work camp. In fact, by August 23, 1942 the average work week lasted from 80-100 hours for anyone older than 14. Due to over-work, punishment, torture, starvation, and disease, approximately 150 Jews died every day. In “this place of famine and of fear… children saw everything that the grown-ups saw: the executions, the funeral carts, the speeches, the shouts of the SS-men at roll call.” (Volavková 1962). Sadly, children rarely survived Theresienstadt. Of the 15,000 children who passed through, it is believed that only 150 survived by the time Theresienstadt was liberated by the Soviet army on May 7, 1945. Terezin website

My Search for Answers

How did I get to Theresienstadt, meet its post-World War II director, and begin to learn about the artists and their creative work in the ghetto camp? In 1971 I convinced my new husband that we should include Prague on our honeymoon itinerary, hoping we could visit nearby Theresienstadt. We were able to get rare visas to visit Communist Czechoslovakia; then a family friend and Holocaust survivor, Eddie Grosmann (Zelle 2014) wrote us a letter of introduction to Dr. Karl Lagus, the director of the Theresienstadt site.

Though our visit occurred 26 years after the Russians had liberated the ghetto camp, not even a sign announced the name of the place. Perhaps the government reasoned that no tourists would arrive, or that none would think that the Czech government had colluded with the Nazis. Thanks to our personal tour conducted by Dr. Lagus, we got a full and horrifying picture of what happened there. For example, he explained that in 1944, the Nazis duped visiting representatives of the International Red Cross (ICRC), the worldwide organization known to help people in need. The Red Cross was convinced by the Germans that Theresienstadt was a model place for Jews to live, subsequently endorsing the Nazi propaganda film, Theresienstadt: Dokumentarfilm aus den jüdische Siedlungsgebiet “Theresienstadt: A Documentary Film from the Jewish Settlement Area.” Screened at locations in Europe and the United States, the film falsely portrayed Theresienstadt as a charming place, deceitfully showing Jewish families from all over Europe gardening, playing soccer, and buying delicious food and goods in shops seemingly filled with fine merchandise. It showed performances of a professional orchestra, opera, and Brundibár, a children’s musical choreographed by Kamila Rosenbaumová. The audiences in the film seemed to be well fed, happy people. As a result of the Nazi campaign, the Red Cross saw no need to help the Jews in Theresienstadt.

With Dr. Lagus, we learned the reality of how children were forced to live in barracks separated from their parents. All adults were housed under terribly crowded conditions. The buildings we saw looked only recently abandoned, with wide wooden slats used for beds attached to the walls, one above the other, once crammed with people. We walked across the ghetto to the rampart walls, where hidden from view stood the small crematoria near the train tracks. Dr. Lagus told us he hoped to build a museum with paintings by artists who had been imprisoned and perished in Theresienstadt, with information about the theatre, concerts, opera and childrens’ musicals as well as a memorial to those who were sent to other camps. That museum, the Terezin Memorial, has since been built, with archives and a restoration of the little upstairs theater where Broučci performances took place.

In 2014, I returned to Terezin and found in the archives a seemingly cheerful poster advertising the performances for the children’s opera Brundibár. Popular with all who came to see it, Nazis officers realized the potential of including it in their propaganda film, creating rare documentation of this children’s musical.

First Encounter with dancers in Theresienstadt

After our 1971 visit to Terezin, I kept hunting for information about dance performances in the camp. Years later I read the autobiography of dancer Helen Katz (later Lewis) who grew up in Trutnov, Czechoslovakia, studied and performed in dance productions in Prague, and was deported to Terezin on the 5th of August 1942:

When we finally arrived, half delirious from thirst and fatigue, we were herded into some obscure building and left for hours without food or water…A young uniformed nurse who gave First Aid turned out to be my friend and fellow dance student, Hana…Next morning she took me to the ramparts, the fortress walls overlooking the ghetto which had been planted with grass, and there on the green slopes, I saw a group of young women dancing. I did not even try to understand, I just joined in. And so it was that I spent my first morning in Terezin dancing on the ramparts.…I started work in the children’s home…proper teaching was strictly forbidden on the principle that Jewish children were to be kept uneducated as a punishment for being Jewish. [However] if the weather was good, I would take my charges up onto the ramparts, where we danced to the accompaniment of our own voices. All of us who lived and worked with the children deliberately and actively disobeyed the ‘no schooling’ orders, but we had to appoint lookouts to warn of any approaching danger. Even so, most teaching was done by word of mouth…We tried very hard to keep the children mentally alert, to engage them in interesting and amusing physical activities. (Lewis 1992, pp. 39-40)

I encountered my next clue about dance in Terezin at an art exhibition in the Simon Wiesenthal Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles in 2001. The name Kamila Rosenbaumová and label of choreographer accompanied two small costume designs by Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. Unbelievable to me, it said the costume designs were for dances performed in Theresienstadt. Looking at the watercolors, I couldn’t stop wondering how were there dances in a ghetto, costumed so beautifully, on dancers depicted as so well trained?

How could I find information about Rosenbaumová and her dances, when all seemed to have disappeared in the void of Theresienstadt and the Holocaust? At the Museum of Tolerance, I bought the exhibition book about featured artist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, who painted the two watercolors. From the book I learned that Rosenbaumová and Dicker-Brandeis had worked together on a dance project in Theresienstadt, and that both artists were later deported to Auschwitz. The catalogue explained Dicker-Brandeis was murdered there. I wrongly assumed that Kamila Rosenbaumová was not only deported to Auschwitz but murdered there as well. It took me almost fifty years to learn about Rosenbaumová’s career, her work with children, and her fate.

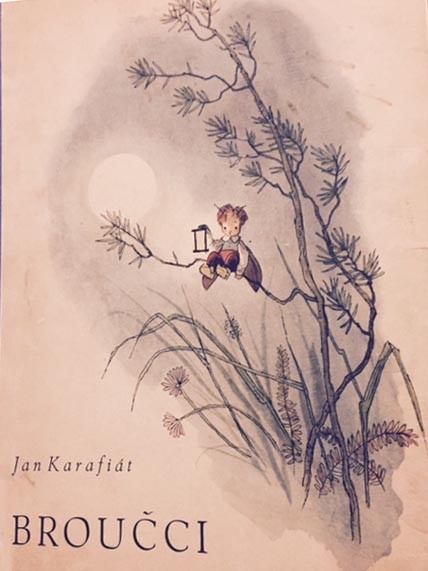

Rosenbaumová was deeply linked to Dicker-Brandeis, through their work creating the children’s musical Broučci, “Fireflies”. It was based on Jan Karafiat’s famous Czech children’s book, Broučci, a perpetual favorite about a little firefly. Many children brought this beloved book with them to Terezin.

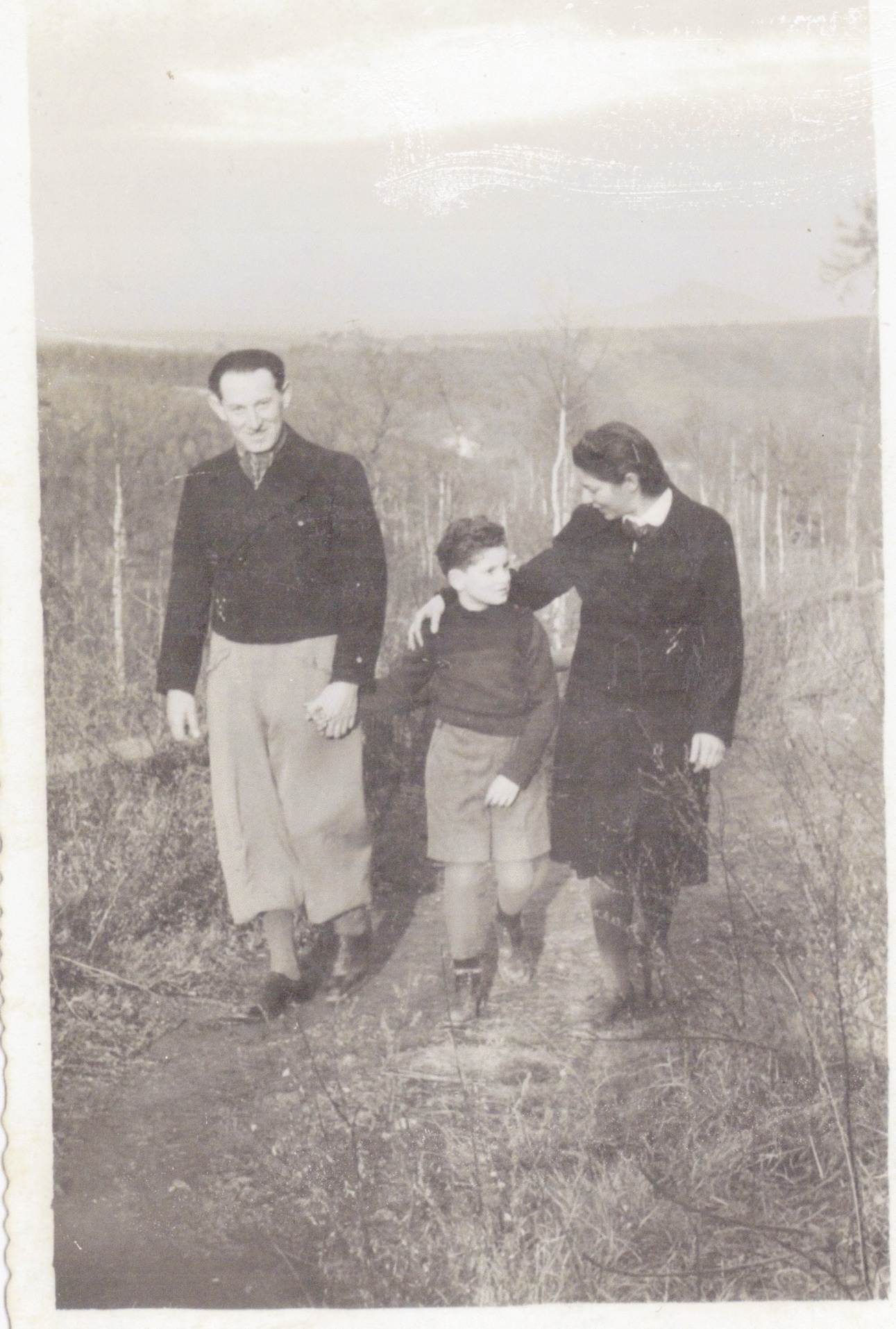

Rosenbaumová arrived in Terezin with her seven-year-old son Ivo and her husband Paul Rosenbaum. Perhaps Ivo also brought his copy of Broučci among the meager possessions allowed in his suitcase. Children over the age of four lived in barracks called “Children’s Houses,” so Ivo was separated from his parents. Divided by gender, each barrack was overseen by “house parents.” Although the Nazis officially banned teaching, the house parents and those who “visited” the children in the evenings would secretly disguise lessons as songs, plays, games, or storytelling. Rosenbaumová became a house parent for a room in the girls’ barracks #L410, inventing unusual dance sequences. These became the basis for the musical she choreographed.

There were 35 performances of Broučci held in two different locations in Terezin. The first series began in May of 1943. A second set of performances took place in 1945 after three of the four creators and many of the children had been transported from Terezin to extermination camps — primarily to Auschwitz. (Makarova 2001, p. 238).

Adult prisoners in Terezin tried to make life as normal as possible, but children were still hungry, ill, and afraid (Thomson 2018, 38). Those caught teaching the children were punished. Nonetheless, the artist, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis was one of the secret teachers. She taught art in the children’s barracks, held art exhibits of the children’s work, and gave lectures to adults about why art classes were important. Despite everyone over 14 working up to 100 hours a week, in the evenings there were concerts, lectures and gatherings.

It wasn’t until 2010 at the Yad Vashem archives that I discovered the autobiography of Broučci director Nava Shean, To Be An Actress. In it, Shean recounts:

One of the counselors in the children’s house was Camilla Rosenbaum (sic) [a.k.a. Kamila Rosenbaumová] who before arriving at the camp was a professional dancer. She told the stories of the fireflies to the children in her group and taught them to dance according to the text in the book. Once the children could happily perform the dances of spring, winter, snowflakes and sun rays, Camilla decided to put together a show for all the children in the camp…I could see immediately there was groundwork for developing something bigger…. I adapted the book into a play…I adapted the play to Camilla’s dances…thus a show was created for scores of participants. (Shean 2010, 33).

Painter and set designer Freidl Dicker-Brandeis understood the therapeutic power of artmaking. When she and her husband were deported to Terezin she filled her allotted two suitcases with art supplies. She also took bedsheets which she had dyed green. “Friedl decided right away that bedsheets would be used in plays they would stage with the children. For example, a sheet dyed green, thrown over the children, would represent a forest. ….” (Makarova 2001, 28).

Children in Dicker-Brandeis’ art classes produced the incredible paintings I had found so inspiring in the book, I Never Saw Another Butterfly. Dicker-Brandeis’ art classes were vehicles for self-expression and therapy, resulting in the outpouring of children’s artwork from Theresienstadt. This unsung heroine even organized clandestine art exhibits in the basement of Barrack L417.

In addition to [art] classes, Friedl worked with the traumatized and the infirm. A group of children from Germany arrived whose fathers had been shot before their very eyes. They were in a state of severe shock, clinging to each other…[nonetheless] she sternly informed the children they needed clean hands to draw. To the great delight of the children, she brought them paints and paper and soon they were caught up in Friedl’s lesson. (Makarova 2001, p.31).

Broučci, A Musical in Three Scenes

The Broučci poster states that the musical was based on a fairy tale by the Czech writer J. Karafiat, choreographed by Kamila Rosenbaumová, “adapted for the stage by the director, Vasja.” Vlasta Schoen, aka Vava Schönová, Vasja, or Nava Shean, wrote that at 20 she began doing solo theatre presentations for adults in the ghetto. “I don’t think it was the desire to escape from reality but rather it’s more accurate to say that the cultural activity provided a genuine expression for the desire to prolong our internal life and not let the external conditions affect that life. It was the wish not to surrender to the sub-human conditions.” (Shean, 2010, p. 34)

Composer Karl Schvenk (Švenk) taught the children the Czech folksongs he incorporated into the score for Broučci. He surreptitiously also included elements of the Czech national anthem into the score. He performed in Terezin cabarets with choreographer Rosenbaumová and director Schönová. In the Ghetto Archives, a sheet advertising a play called Esther caught my eye, showing the names of two dancers: Trauta Lachová, and Kamila Rosenbaumová. Even the assimilated Jewish artists in Theresienstadt could relate to the beloved Biblical story of Queen Esther outfoxing the wicked Persian Haman and his plot to kill the Jews.

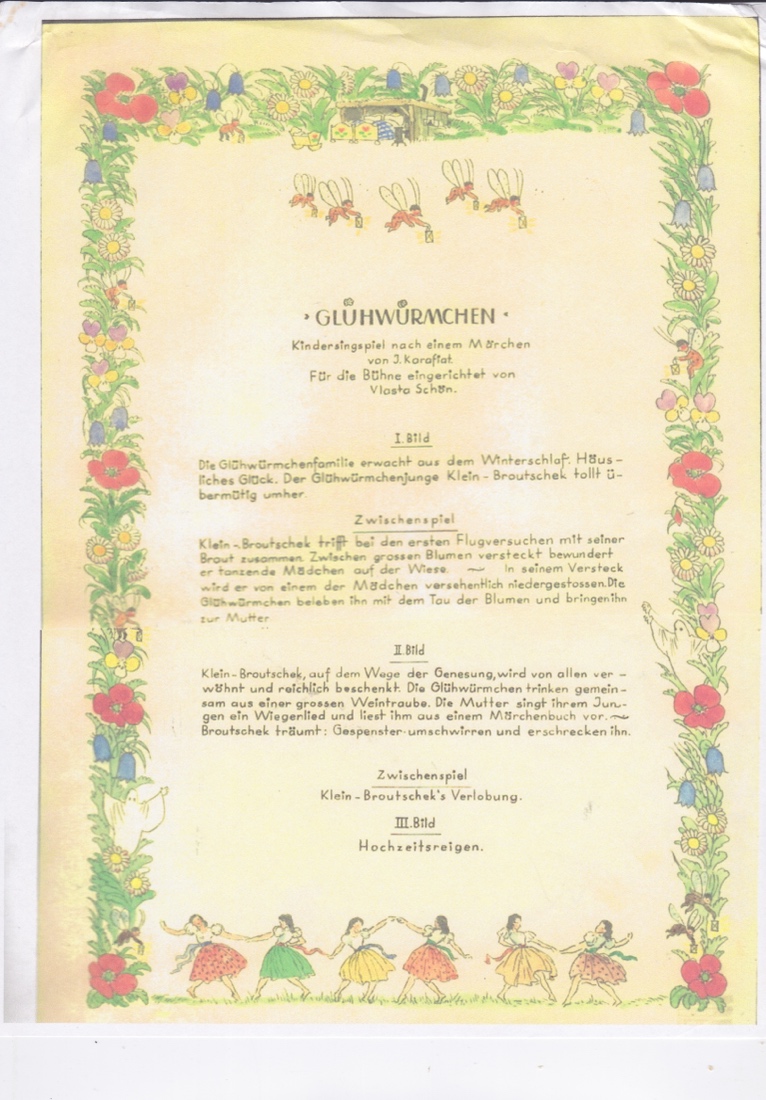

Later, I discovered another priceless document in the Prague Spanish synagogue: a sheet written in German with the title Gluhwurmchen “Fireflies” and decorations in the margin. Four little brown fireflies were shown holding lanterns of white lights. Spring flowers in red and blue interspersed with drawings of little white ghosts, and six young girls danced by the text, “a children’s play based on a fairy tale by J. Karafiat, adapted for the stage by Vlasta Schoen.”

I realized with jubilation that the whole musical was described on that one page in German (It’s not surprising someone wrote the synopsis in German because so many different languages were spoken in Terezin, especially Czech, German and Yiddish). This is the story of Broučci:

Scene I: The firefly family wakes up from its winter slumber. The little boy firefly, Brouček, runs wild all over the place. Between large flowers Little Brouček hides and admires dancing firefly girls in the meadow. While in hiding, one of the girls carelessly hits him and he falls down to the ground and his wing breaks.

Scene II: While convalescing, little Brouček is pampered by everyone, receiving lots of presents. The fireflies drink together from a large grape. Recuperated, Brouček flies over flowers and fields, falling in love.

Scene III: A wedding with circle dances.

This simple summary provided me with a mental image of the children’s roles and their dances.

A Rare Interviewee

The second series of Broučci productions, performed in 1945, were described to me in detail by Vera Meisels, child survivor of Terezin. I originally learned of Meisels through her poem, translated into English in the archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM)in Washington, D.C.:

Firefly

To Naava Shean, Theatre Director in Terezin

The firefly pushes through the leaves,

Often covered completely, its glow

Hidden to near extinction…

On the Terezin ghetto stage, I danced…

Afterwards I learned they just wanted to prove

That culture distracts the mind from hunger.

(Meisels, V. unpaginated single poem, USHMM archives)

In September 2015 I had the privilege of interviewing Vera Meisels in Tel Aviv. She shared priceless information about what it was like to perform as a child in Broučci. A flower she drew in the ghetto camp graces the cover of her newest book, her autobiography, Threshold of Pain (2020). The original artwork can be found in the exhibit “Children of Terezin” in Israel’s Beit Terezin Archives.

Meisels was born in Bratislava, Slovakia in 1936, the same year the Nazis invaded Slovakia. At first, she and her family escaped by hiding in the forests but eventually they were caught and sent to Theresienstadt. She was imprisoned in 1943, surviving and avoiding deportation until the camp was freed by the Russians in 1945. Meisels wrote,

I only recently learned that the play was staged also before my time in the ghetto and that I replaced a girl who was sent to Auschwitz in October 1944, in one of the last transports. I arrived on the 23rd of December, that year… The production included dancing and singing by characters such as fireflies and a ladybird [ladybug] Beruška. I was the ladybird. The many rehearsals kept us busy and full of the joy of creativity. We knew [the performance] was really going to happen when we were measured for our costumes. These are childhood experiences one does not forget.” (Meisels, 2020, p. 174)

During our interview she fluttered her arms as wings, saying, “I exactly remember the arm gestures.” She sang and translated one of Broučci’s theme songs: “‘The spring will come, and again it will bloom and the fields will be green’…Although the words are rather optimistic, we didn’t know exactly when the war would end. The play was performed several times in the months before the Liberation…I think there were hints of death [in the play]; there was a grandmother fly who died. Children have to understand there’s death and life together. The play wasn’t something to give us hope, it wasn’t about a black or white vision, it was a way for us just to keep going. As a child we had many rehearsals, and we all rehearsed many parts. We never knew who would be present for the next rehearsal or for the performances because there was illness; so many might be sick and absent, perhaps ten children rehearsed for each role. A child you knew and rehearsed with might simply disappear and be gone because there were deportations all the time. One never knew who would be missing.” (Meisels, V. interview 2015)

From what Vera Meisels told me, the 1945 performances took place in an attic theatre, quite a different venue than where the first 1943 performances occurred, in the children’s barracks. The attic theatre had been built for cabaret and theatre productions. One performance deeply haunted her. A group of SS officers who had come to watch the show removed their helmets, placing them on the edge of the stage with the Nazi skull and crossbones emblems facing the children. She wrote,

Were the skull and crossbones a warning for the children that the SS officers would kill us after the show? After the performance I thought, they’re going to take us. After all, children aren’t productive. This was the end of us – we were going to die. This is what I had learned at the Selection. It was all a ruse! I was trembling all over. There were no parents to lean on. It was as if they had invested in us for their own amusement. Now it was over. Finished! … My eyes were almost bursting from their sockets, when I saw that the audience had risen as if in salute and was on the way out of the hall. Nava and some others came over with hugs and kisses, to praise, caress and encourage us. Everything was as it was before. It took me a long time to calm down. For three years until that moment, I was poisoned with the pessimism that characterizes me to this day. At the time of that horrifying experience, I had already heard it said that I was ‘going to the slaughter.’ Standing in line at the Selection, I already heard that children, old people and mothers with small children were destined for Auschwitz – for the gas chambers. (Meisels, 2020 p. 176)

What Happened to the Artists?

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis was deported to Auschwitz on October 6, 1944 on transport #167. Before she left, she asked her student Willy Groag to help pack the two suitcases in which she’d brought arts supplies and the green sheets used in Broučci in 1942. This time, they filled the suitcases with as many children’s drawings as they could fit, hiding them in the rafters of the Home. Dicker-Brandeis was gassed in Birkenau on October 9, 1944. (Makarova 2001, p. 238)

Willy survived the war, returning to Theresienstadt to recover the suitcases and bring them to the new Jewish Museum in Prague. The drawings were carefully catalogued and became the basis for the book I Never Saw Another Butterfly. Others are also credited with saving artworks and poetry, including Mrs. A. Flachová of Brno whose husband had been a teacher in the L417 children’s home, as well as individual survivors who were able to saveillustrations and poems.

I learned in the archives at Kibbutz Givat Haim that Jana (or Yana) Urbanova (n.d.) was only eight in 1945 when she joined the second wave of Broučci performances. By this time Rosenbaumová had also been deported to Auschwitz. In a letter Yana wrote, archived at Beit Terezin, she references the choreographer of the second series of Broučci performances, Mariana Šmeralová. Yana also wrote that few of the children in the play could read “because Jewish children had been forbidden to be in school, so we had to memorize everything… It was so incredible for us children to see a play, let alone to be in one. It influenced us from then on. The music was so wonderful, too, and the dance. It raised up our souls. I thought there’s simply nothing in this world as wonderful as theatre.” (Urbanova, Y. letter #94)

I had wrongly assumed Kamila Rosenbaumová, like the three other creators of Broucci, had perished in the death camps. A surprise email from her daughter Kate Rhys revealed the truth: after the deportation to Auschwitz, Rosenbaumová’s son Ivo and husband Pavel were murdered but Kamila survived. After the war she married again and had two daughters, Kate and Mariana.

Kate and I began corresponding and I finally learned more about Rosenbaumová’s long, creative life before World War II, during the war years, and afterwards when she remarried and returned to teaching children and actors. Kate knew her mother was born in Vienna in 1908 to a Czech couple, who then moved back to Prague where Kamila grew up in meager circumstances though she apparently studied ballet, folk, and modern dance. She worked with an avant–garde artists’ group imbued with Socialist ideals before the war, providing free lessons including folk songs and dances for children to easily pick up well-known movements. These simple steps were incorporated into group movements with moral points assailing the inequities of economic life in Prague, criticizing politicians and the bourgeoise.

Kate knew little about the war years but shared that “Mum did expressive dance movement which she incorporated into performance. After all, Mum did that with other performances too, such as in Brundibár where she taught Ela Weissberger who played the cat, not only how to move as a cat on the stage, but also how to dance the waltz…” In 1944 “my Mum, together with her son Ivo and a girl named Eva Wollsteiner [b. 1931] whom she had informally adopted in Terezin were transported to Auschwitz. Immediately after their arrival they were separated and both Ivo and Eva were gassed…” After several days in Auschwitz, Rosenbaumová was sent to a labor camp in Germany. After the War, she learned that her husband Pavel had been gassed in 1944. Rosenbaumová met Ing Otto Guth who had sung next to Pavel in Raphael Schaechter’s male choir in Terezin. “Mum did not want to remain paralyzed by the tragic past,” Kate wrote. She married Guth with whom she had Kate in 1946 and her sister Mariana two years later.

“When I started searching for information about my Mum,” Kate wrote me in a 2015 email, “I knew very little about her previous life, especially about her time in Terezin. Mum didn’t talk about her past much, except for a brief mention of some performance she did with the children in Terezin. While quite young, me and my sister attended a local school and Mum led several after-school classes of movement to music, dancing and ballet, which we both attended. I remember us taking part in a performance of Broučci wearing brown outfits with sequins and antennae and scurrying around the stage with a lantern in one hand. I loved the book, so assume I must have been thrilled to do the performance. Of course, at the time, I had no idea about the connection to Terezin.”

Kate noted the renewed interest in Broučci,“After a long interval, interest in the cultural life at Terezin is growing again and the children’s performances provide an especially important resource for Holocaust education. These performances were important for the spiritual life of children and youth. It is just as important for the children of today to have an opportunity to learn about the tragic past…” (Rys, Dec. 5, 2015)

Kamila Rosenbaumová was born in 1908 and died after a surprisingly long and rich life on July 26, 1988, felled by cancer in Prague, the town she considered home. I have continued to teach about her, writing articles and creating dance programs. My biggest endeavor was to recreate Broučci at the Czech Slovak Sokol Center in St. Paul, MN. An exhibition accompanied the performances which included photos, tape recordings, interactive components about Czech survivors in Minnesota, as well as information about Rosenbaumová and her three fellow creators of Broučci.

The original creators of the musical Broučci took its message quite seriously. Through an imaginative, enchanting story, they found a metaphoric way to give performers and audiences a moment of respite, a path toward hope. The Czech national anthem, embedded in the tunes of Broučci, implied that the Nazi aspirations would not triumph. Ultimately, at the end of every Broučci performance, the children were strong and free, frolicking in the springtime they had created, despite what might be lurking offstage. Onstage, they survived to play and love and magically marry, celebrating life in dance and song.

Broučci (Fireflies)

FIGURE 9: Vimeo of St. Paul performance by author/choreographer Judith Brin Ingber

In honor of the original, I recreated the musical in 2016 with musician Craig Harris and dancer-assistant Blanka Brichta at the Sokol Czech Slovak Center in St. Paul, MN with 42 children.

Key Artists for Broučci:

- Choreographer: Kamila Rosenbaumová, also choreographed the other children’s musical in Theresienstadt, Brundibar and danced in many cabarets and musical productions;.

- Composer Karl Schvenk, also composed many cabarets and musical productions in Theresienstadt.

- Director: Vava (a.k.a. Vlasta ) Shoenova, also performed in other dramas in Theresienstadt. She later wrote her autobiography To Be An Actress (under her Hebrew name Nava Shean);

- Painter/Set Designer/Costumer: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, also known for teaching drawing to children in Theresienstadt. These drawings were found after WWII and collected in the book I Never Saw Another Butterfly; Children’s Drawings and Poems from Theresienstadt Concentration Camp, 1942-1944 (1962).

- Child performer: Vera Meisels; Her recent autobiography Threshold of Pain, provided important information about the production Broučci.

Acknowledgements:

I wish to thank Ruth Eshel for her original encouragement that I should write up the challenge of researching the life and work of choreographer Kamila Rosenbaumová. It was my honor to have the article included in Dance Today #36, published in Israel in September 2019.

I also acknowledge Yehudit Shendar’s encouragement when she was deputy director and senior art curator of the Art Museum at Yad VaShem. She translated the German flyer about Broučci and gave me Shean’s autobiography to read. Her own extensive writing includes information about the dancer Catherine Frank who was imprisoned in Westerbork and Terezin and was a model for painter Charlotte Bureshova.

References

Brundibar Arts Festival Poster, n.d., (accessed July 4, 2019).

Gremlicová, D. ( 2012). Eds. Dunin, E.I., Stavelová, D. and Gremlicová, D. “Traditional Dance as a Phenomenon Inside the Czech Modernism,” Dance, gender and means; contemporizing traditional dance, music: heritage, changes, authenticity”, Academy of Performing Arts and AMU Press Publishing.

History of Terezin. Terezin. (n.d.). Retrieved February 13, 2023, from History of Terezin

Ingber, J. B. (2011). “Vilified or Glorified? Nazi versus Zionist Views of the Jewish Body,” Seeing Israeli and Jewish Dance. Wayne State University Press.

Ingber, J. B. (September, 2019). “Correcting a published error: ‘Kamila Rosenbaumova, the choreographer of Theresienstadt’s Broučci and Brundibar died in Auschwitz’ and other quandaries,” Dance Today; the dance magazine of Israel, #36.

Ingber, J. B. , (2012) Video recording of “I never saw another butterfly” choreographed by Brin Ingber, performed by Megan McClellan, music by Jim Miller

Ingber, J. B., (2016), Video recordings by Nancy Mason Hauser of Sokol Hall “Broucci” performances:

Broucci (Fireflies);

Broucci Behind the Scenes

Lewis, H. (1992), A time to speak, Carroll & Graf Publishers.

Kulisova, Tana, Karel Lagus, Josef Polak, (1967), Terezin, Z Historie (in Czech).

Makarova, E. (2001), Friedl Dicker-Brandeis; Vienna 1898-Auschwitz 1944; the artist who inspired the children’s drawings of Terezin, Simon Wiesenthal Center Museum of Tolerance.

Meisels, V., Riva Rubin, trans. (2020). Threshold of Pain. E-book.

Meisels, V., Terezin’s firefly; poems by Vera Meisels, WordPress.com.

Meisels, V. (2015), Petitai zichronot (Shreds of memory), Steimatzky.

Meisels, V. September 3 and September 20, 2015, Interview with author (in Hebrew, translated by author).

Peschel. L, Ed. (2014). Performing captivity, performing escape; cabarets and plays from the Terezin/Theresienstadt ghetto. Seagull Books.

Rubin. S. (2000). Fireflies in the Dark; The Story of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis and the Children of Terezin. Holiday House.

Rys, K. E-mail correspondence with author, 2015-2020.

Rys. K. “Remembering Our Mum Kamila.” 2016.

Shean, Nava (2010). To be an actress. Hamilton Books.

Sendak, M. and Kushner, T. (2003). Brundibar. Michael Di Capua Books/Hyperion Books.

Shendar, Y., (January 2002), “Humor and melody: cabaret at the Westerbork transit camp,” Yad Vashem Magazine 25: 10-11.

Šiknerová, M., (March 23, 2021), librarian in Terezin Collection. Email correspondence with author, confirming difference between Nazi ghetto Theresienstadt and Czech town of Terezin.

Thomas, R. (2011), Terezin, voices from the holocaust. Candlewick Press.

Urbanova, Yana, letter marked 94, in the Children’s Museum at Beit Terezin, reference to choreographer Mariana Šmeralová (sic) n.d.

Volavková, H., Ed., (1962), …I never saw another butterfly…; Children’s Drawings and Poems from Theresienstadt Concentration Camp, 1942-1944. McGraw-Hill with the State Jewish Museum in Prague.

Weil, J., (1962), “Epilogue, a few words about this book”, …I never saw another butterfly…; children’s drawings and poems from Theresienstadt concentration camp, 1942-1944, New York: McGraw-Hill with the State Jewish Museum in Prague, (no pagination).

Weiss, H., (2013). Helga’s diary; a young girl’s account of life in a concentration camp, W.W. Norton.

YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Gershon, D.H., Ed., (2008). Yale University Press. 375-380.

Zelle, L. and J. Sussman, editors. Witnesses to the Holocaust; Stories of Minnesota Holocaust Survivors and Liberators. Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas. 2014, 72-78.

Golem (Hebrew and Yiddish) a creature formed out of a lifeless substance such as dust or earth that is brought to life by ritual incantations and sequences of Hebrew letters. The golem, brought into being by a human creator, becomes a helper, a companion. Jewish Museum Berlin

Located in the German-occupied region of Czechoslovakia, Theresienstadt was a ghetto-labor camp, while Nazi propaganda framed Theresienstadt as a “spa town” where elderly German Jews could ‘retire’ in safety.Wikipedia

Terezin, or Theresienstadt, was a concentration camp 30 miles north of Prague in the Czech Republic during World War II. It was originally a holiday resort reserved for Czech nobility. Terezín is contained within the walls of the famed fortress Theresienstadt. The History of Terezin

Theresienstadt: eine Dokumentarfilm aus den jüdische Siedlungsgebiet, (German) “Theresienstadt: A Documentary Film from the Jewish Settlement Area.” After successfully deceiving the Red Cross representatives, two Nazi authorities then decided to make a propaganda film on location at Theresienstadt. The film's "cast," musicians, and director Kurt Gerron were all prisoners of Theresienstadt. The film was made under the close supervision of the SS. A production company was hired from Prague to produce the film, along with a Czech photographer and cameraman named Ivan Fric. The film was shot between August and September of 1944 but was not completed until early 1945. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Brundibár is an opera written for children, composed in 1938 by Hans Krása, with lyrics by Adolf Hoffmeister, as an entry for a children’s opera competition. In July 1943, the score of Brundibár was smuggled into [Theresienstadt], where it was re-orchestrated by Krása for the various instrumentalists who were available to play at that time. The premiere of the Terezín version took place on 23 September 1943 in the hall of the Magdeburg barracks…the same production was performed for the inspection of Terezín by the International Red Cross in September 1944. Music and the Holocaust