Settings

France: World War II Occupation and the Holocaust

Eileen M. Angelini

Sections

Acknowledgements

I have had the tremendous fortune of having been able to interview and videorecord the testimonies of Holocaust survivors, hidden children, members of the French Resistance , Righteous Gentiles, French historians, and U.S. servicemen who were in France as part of the D-Day Invasion. By reading this chapter you are allowing me to maintain my promise to each and every one of these individuals that their stories and efforts will not be forgotten. From the bottom of my heart, merci mille fois “a thousand thanks”.

Inspiration for this chapter grew out of Incorporating the Lessons of the Holocaust into French Classes: An Instructor’s Resource Manual (Angelini and Barnett, 2001). This manual was part of a series of 1999-2002 American Association of Teachers of French (AATF) projects that were generously supported by a Title VI Grant from the U.S. Department of Education. For this project series, entitled “Taking French into the Next Century: The Development, Production, and Dissemination of Multimedia Instructional and Promotional Materials,” I co-authored the grant proposal with Steven Sacco and served as Co-Project Director with him.

Introduction

This chapter offers an introduction for understanding the interdisciplinary lessons of the WWII Occupation of France and France’s role in the Holocaust. It is accompanied by two examples of survivor testimony. Essential to keep in mind is the problematic position in which France found itself as it was defeated by the Germans (June 12, 1940), occupied by the Germans (June 14, 1940), collaborated with the Germans (July 1940), and declared victory over the Germans (June 6, 1944: Allied landing in Normandy, France; August 25, 1944: Liberation of Paris by the Allied forces). Let’s dissect these four elements in greater detail.

The German invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium, and France took place between May 10, 1940, and June 25, 1940. It is noteworthy that, during this short period of time, Germany forced the British Expeditionary Forces off the continent of mainland Europe. After the fall of France, General Charles de Gaulle, in a June 18, 1940 radio broadcast from London, called for continued resistance. France Libre “Free France” was the government-in-exile led by de Gaulle. “Free France” fought the Axis powers as a member of the Allied forces with its Forces françaises libres “Free French Forces”. “Free France” also supported the Resistance in Occupied France, the Forces françaises de l’Intérieur “French Forces of the Interior”, and gained strategic footholds in several French colonies in northern Africa. The use of un tract “a tract”, a pamphlet or leaflet used for political or religious purposes, by the French Resistance kept citizens aware of the dangers of the Vichy Government’s collaboration with Germany.

After Paris was captured, the French government surrendered to the German government. Germany then established the occupied zone in the northern half of France and, in July 1940, let the French set up their government in the southern zone at Vichy under WWI hero Maréchal Philippe Pétain. Pétain’s government came to be known as the Vichy government because of its location. Specifically, the southern zone at Vichy was called the la Zone libre “Free Zone” and was the southern two-fifths of France not occupied by the Nazis prior to 1943. Many Jews left Paris for the “Free Zone,” where they sought refuge from the Nazis and French police. Jews fleeing the Nazis were often aided by un passeur “smuggler”, a person who was paid to help Jews cross the demarcation line from the northern zone occupied by the Germans to the “free” zone controlled by the Vichy government. A “smuggler” was also someone who assisted Jews, Resistance fighters, members of the Allied Forces who had parachuted into France, and other targeted by the Germans to cross over the Pyrenees mountains from France into Spain.

The French people trusted Pétain because of his success at the Battle of Verdun during WWI. In addition, because he was 84-years old when he became President of France under the Vichy government, Pétain projected a grandfatherly image. French and German propagandists use this grandfatherly image to their advantage, exhorting the French to have complete faith in Pétain as Pétain pledged that he would give his body and soul to protect France. With Pétain as President of France, Pierre Laval was Prime Minister, the person in charge of the French government. The propagandists’ efforts were extremely necessary to combat negative sentiment. For example, strict rationing of food and gasoline was one of the first actions undertaken by the Vichy government, resulting in the emergence of an active black market. Moreover, Jews were only allowed to use food ration coupons at the end of the day, after other French citizens have used theirs, resulting in Jews having extremely limited access to the worst of the food supplies.

In May 1941, the first round-ups of foreign-born Jews in France began. These foreign-born Jews were either interned in camps in France (many in the southeast of France had previously been used for Spanish refugees fleeing Franco) or deported, via Drancy , to camps in eastern Europe. Then in June 1941, the Vichy Government enacted its Statut des Juifs “Statutes for Jews”, replacing the Law of 3 October 1940 and defining an increasingly stringent definition of who was a Jew in France. This new set of laws excluded Jews from top positions in government, the military, and the professions of teaching, radio, the press, and theater.

Collaboration with Nazi authorities who occupied France took many forms. People who traded goods on the Black Market were viewed as collaborators. Government officials (whether elected or appointed) worked with German officials and then even took action to further the German agenda against Jews without pressure or influence from the Germans. For example, Prime Minister Laval and Secretary General of the French National Police Renee Bousquet who orchestrated the July 16-17, 1942, Vel d’Hiv round-up, the largest mass arrest in France in wartime in French history that included, for the first time, the rounding-up of Jewish children. What made the Vel d’Hiv round-up so shocking was that the Vel d’Hiv round-up was planned and executed by the Vichy government, policemen and other civil servants. German orders originally included only adult Jews. It was the French government that decided to arrest the children in addition to the adults. Approximately 13,152 Jews were arrested and sent to Vel d’Hiv. It is estimated that almost 4,115 of them were children. This single event accounted for a third of all of the Jews that were sent to concentration camps in 1942. After the Vel d’Hiv round-up, more and more French people began to lose faith in Pétain. Bousquet silenced the protests of the French Catholic Church by threatening to remove all tax privileges they received. Indeed, the Vel d’Hiv round-up was a pivotal moment during the Occupation, marking a significant change in public sentiment for Pétain as well as notably by members of the French Catholic Church who had previously supported Pétain. After WWII, Laval was tried by French court and hanged in 1945. See the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s, USHMM, entry on the Vel d’hiv round-up for further detail on the preparations for the round-up and President Jacques Chirac’s official apology in 1995.

The Vichy Government collaborated with Germany and as result, via propaganda, influenced French citizens to believe that collaboration was the correct path to follow. Moreover, in January 1943, the Milice “milita”, a paramilitary organisation, was set up in France. The Milice first supported the Vichy government in unoccupied France but was later used in German-occupied France where it supported the Nazi government in Paris. Even so, by the end of WWII France was recognized as one of the Allied powers and declared victory over Germany. The “Free French Forces” and the Comité français de Libération nationale “French Committee of National Liberation” continued to work with the other Allied powers, the United Kingdom, United States and the former Soviet Union. The enemies of the Allied powers were the three principal members of the Axis alliance, specifically Germany, Japan, and Italy.

Nonetheless, during the Occupation of France, one cannot underestimate the contributions made by the French Resistance, whether armed militarily or not. Some estimate that only 2% of the population was in the armed Resistance, whereas most French people would not claim active membership in the Resistance as they were just trying to survive the war. Yet those who helped Jews by hiding them or providing food were resisting since it was against French law to aid a Jew. These Christians or les Justes “righteous gentiles” who risked their lives to save Jews were later honored by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center.

Following its libération “liberation”, France has undergone a painful process of remembering, commemorating, and coming to grips with this difficult period in its history or les années noires “the dark years”. To frame in a meaningful and concrete manner how France has dealt with les années noires “the dark years” as well as the years that followed the end of WWII, it is highly recommended to consider the four phases of memory of Vichy France put forth by Henry Rousso in Le syndrome de Vichy (Paris: Seuil, 1990)/The Vichy syndrome: history and memory in France since 1944 (Translated by Arthur Goldhammer and foreword by Stanley Hoffman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1994):

- Unfinished Mourning (1944-1954);

- Repressions (1954-1971);

- The Broken Mirror (1971-1974); and,

- Obsession (1974-present).

Two testimonies accompany this chapter. The first is written by the husband of a hidden child, and the second is written by a woman who, as a child with her family, escaped from France to Spain via les Pyrénées “the Pyrenees mountains”. The suggested activities in the sidebar, the Chronology of the Holocaust: Focus on France, the glossary terms in this chapter, and the list of terms and people specific to the WWII Occupation of France will all help students to read these two testimonies and others with greater understanding and empathy. An excellent resource for oral testimonies is the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive Online.

U.S. educators will note that their French-language students may find comfort in being able to express themselves easily via cognates [e.g., camp de concentration = “concentration camp”] and from drawing on knowledge acquired in other classes. To help U.S. students understand the context of the WWII Occupation of France and how the impact of the events of World War II and the Occupation of France still play a major role in the cultural and economic forces at work in contemporary France, the Chronology of the Holocaust: Focus on France includes a focus on the United States viewpoint on entering WWII. For example, while the focus of this chronology is on events that took place in France, the chronology includes events important to both the WWII Occupation of France, Hitler’s strategic plan to dominate the world, and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s actions. In this way, students can see how the rationing of food and gasoline was not unique to one country.

For those seeking current research on the American perspective during WWII and the Holocaust, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM)’s exhibit “Americans and the Holocaust” is an excellent resource (as is the new PBS documentary by Ken Burns). The groundbreaking USHMM exhibit was five years in the making and opened on April 23, 2018 to tremendous success.

Chronology of the Holocaust: Focus on France

As a complement to this chronology, the USHMM’s The Path to Nazi Genocide is highly recommended. In addition, the USHMM Holocaust Timeline Activity is an excellent model that is easily adaptable for timeline lessons with a focus on France as well as for those done in the French-language classroom. For example, students can be encouraged to do further research on a specific event that took place in France during WWII (e.g., the Vel d’Hiv Round-Up) and, for the French-language classroom, illustrate event cards with the art media of their own choosing to accompany their French-language text. Echoes and Reflections also provides timeline of the Holocaust illustrated with authentic photographs that can serve as a source of inspiration to students. In addition, Echoes and Reflections dedicates specific sections of its timeline to France, such as the formation of the Vichy government.

During the period from 1894-1906 , the Third French Republic was complicated by The Dreyfus Affair. Captain Alfred Dreyfus was falsely convicted of Treason in 1894, but later exonerated and reinstated in the military. This series of events divided French society and came to symbolize injustice related to French antisemitism.

Two recent events exemplify how France has come to terms with some of its actions during World War II: On July 16, 1995, at the Place des Martyrs juifs du Vélodrome d’Hiver, President Jacques Chirac officially recognized the Vel d’Hiv round-up; and, on September 30, 1997 in a ceremony at Drancy, France’s transit camp to Auschwitz, Bishop Olivier de Berranger apologized for the silence of the French Catholic Church and its clergy from 1940 to 1942.

Terms and People Specific to the World War II Occupation of France

Key concepts definitions with the assistance of Epstein, Eric Joseph and Philip Rosen. (1997) Dictionary of the holocaust: biography, geography, and terminology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Another source for helping students grasp key concepts is the Key Words column that appears on the right-hand side of the page for each lesson of Echoes and Reflections, such as the lesson on Antisemitism. Especially appealing is the ability to access an audio recording of each word with one click.

Barbie, Klaus (le “boucher de Lyon”)

Gestapo leader stationed in Lyons and responsible for the murder of French Resistance leader Jean Moulin and many Jewish children. Convicted in France in 1987 for “crimes against humanity.”

Benoit, Abbé Marie

French priest in Marseilles and “righteous gentile” who smuggled more than four thousand Jews to safety.

Bousquet, René

Secretary general of the French National Police in Vichy responsible for ordering the Vélodrome d’Hiver (Vel d’Hiv) “Winter Velodrome” round-up in July 1942. He was assassinated in 1993 before being brought to trial for “crimes against humanity.” Christian Didier, Bousquet’s assassin, pled not guilty, claiming the act was justified by Bousquet’s war crimes.

Brunner, Alois

SS major, head of Drancy internment camp and assistant to Eichmann. He was responsible for sending more than twenty-three thousand Jews from France to Auschwitz.

Chambon-sur-Lignon, le

Small farming village in central France whose largely Huguenot population saved thousands of Jews, including American filmmaker Pierre Sauvage.

CFLN, le (Comité français de Libération nationale)

The Comité français de Libération nationale “French Committee of National Liberation” was a provisional government of Free France formed by the French generals Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle to provide united leadership, organize, and coordinate the campaign to liberate France from Nazi Germany during World War II…The committee directly challenged the legitimacy of the Vichy regime and unified all the French forces that fought against the Nazis and collaborators. The committee… evolved into the Provisional Government of the French Republic, under the premiership of Charles de Gaulle.” (Source: Wikipedia)

CIMADE, le (Comité Inter-Mouvement auprès des Evacués)

French organization responsible for rescuing Jews and escorting them to Switzerland.

CRIF, le (Comité Représentatif des Israelites de France)

French organizations representing major Jewish institutions.

Dark Years (les Années noires)

The years following its liberation when France underwent the painful process of remembering, commemorating, and coming to grips with this difficult period in its history.

Death March (La Marche de la Mort)

The Nazis forced camp prisoners to walk toward the center of Germany when Russian troops approached. The Nazis destroyed the gas chambers at Auschwitz and tried to evacuate concentration camps to obliterate evidence of their extermination policy.

Prisoners on death marches were forced to walk long distances without food, water and satisfactory clothing. Many died or were shot by guards along the way.

Denounce (dénoncer)

To turn in Jews and other groups considered undesirable to the S.S. or the Gestapo. People who were denounced were usually taken prisoner by the Nazis and deported to concentration camps.

Deportation (la déportation)

The resettlement of Jews and other groups from France to concentration camps and extermination camps in Germany, Poland and Eastern Europe. French officials and police helped Nazis find Jews and other “undesirables.”

Drancy

The internment camp near Paris where Jews stayed before deportation to Auschwitz. Before the war, Drancy served as police barracks.

Dreyfus Affair (l’Affaire Dreyfus)

A controversial political and judicial scandal that began in 1894 when Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew from Alsace, was found guilty of treason. Pardoned in 1899, he was eventually restored to his rank, promoted and decorated. Political opponents of Dreyfus were known for their antisemitism and the affair aroused a wave of antisemitism in France.

Free Zone (la Zone libre)

The southern two-fifths of France which was not occupied by the Nazis prior to 1943. Many Jews left Paris for the “Free Zone,” where they sought refuge from the Nazis and French police.

Four Phases of Memory (les Quatre phases de la mémoire)

Put forth by Henry Rousso in Le syndrome de Vichy (Paris: Seuil, 1990)/The Vichy syndrome: history and memory in France since 1944 (Translated by Arthur Goldhammer and foreword by Stanley Hoffman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1994):

- Unfinished Mourning (1944-1954);

- Repressions (1954-1971);

- The Broken Mirror (1971-1974); and,

- Obsession (1974-present).

Fry, Varian

American rescuer and “righteous gentile” who saved more than 4,000 people from the Nazis, many of whom were prominent scholars, writers and artists.

Gerlier, Cardinal Pierre-Marie

Archbishop of Lyons and “righteous gentile” who ordered Catholic institutions to hide Jewish children.

Glasberg, Alexandre (Abbé)

Catholic priest converted from Judaism who helped rescue Jews.

Gurs

French internment camp used to house non-French Jews prior to deportation.

Hautval, Dr. Adelaide

French doctor and “righteous gentile” deported to Auschwitz.

Internment Camp (un camp d’internement)

A camp in which foreigners, prisoners of war, or others considered dangerous to pursuing a war effort are confined during wartime.

Jew (juif)

Pejorative term marked on yellow badge triangle in Occupied France beginning in June 1942.

Klarsfeld, Serge and Beate

Nazi hunters in Paris responsible for apprehending Klaus Barbie and documenting the deportations from France.

Laval, Pierre

Vice-premier of Vichy appointed in 1942 tried by French court and hanged in 1945. Responsible for deporting women and children as well as men.

Leguay, Jean

Vichy police chief and director of transit camps in French Occupied Zone.

Les Milles

Detention camp in southern France.

Liberation (la Libération)

Allied forces liberated Paris in August 1944. General Charles De Gaulle marched victoriously into Paris on August 25, 1944. The Liberation was followed by joyous celebration in the streets as well as a sense of joy and optimism that lasted many months.

Maquis (le Maquis)

French underground active in the Massif Central.

Milice (la Milice)

Pro-Nazi Vichy French paramilitary of 30,000 formed in 1943 to support German Occupation and Pétain. It was active until August 15, 1944.

OSE (Œuvre de Secours aux Enfants israelites)

Society for the rescue of Jewish children. From 1938 to 1944, several thousands of children were saved from deportation by the OSE by rescuing, hiding, and helping them escape into Italy, Switzerland, Spain, and the United States.

Papon, Maurice

Vichy official involved in deporting 1690 Jews. Convicted for “crimes against humanity” in 1998. After 14 years of bitter legal wrangling, Papon finally went to trial on 8 October 1997. His trial was the longest in French history and did not finish until 2 April 1998.

Pétain, Maréchal Henri Philippe

After the fall of France, the National Assembly voted to suspend the constitutional laws of the Third Republic and gave World War I hero Maréchal Pétain full power as Head of State. The new government of Unoccupied France made its capital in the resort town of Vichy in South Central France.

Pithiviers

French internment and transit camp sixty-five miles south of Paris.

Resistance (la Résistance)

Opposition to Nazi occupation.

Righteous gentiles (les “Justes”)

Christians who risked their lives to save Jews later honored by Yad Vashem in Israel.

Rivesaltes

French internment camp in southern France near Spanish border.

Saliège, Monsignor Jules-Gérard

Archbishop of Toulouse who actively opposed Vichy’s anti-Jewish measures.

Shoah (la Shoah)

The Hebrew word for the Holocaust.

Smuggler (un passeur)

A person who was paid to help Jews cross the demarcation line from the northern zone occupied by the Germans to the ‘free” zone controlled by the Vichy government or someone who assisted Jews, Resistance fighters, members of the Allied Forces who had parachuted into France, and other targeted by the Germans cross over the Pyrenees mountains from France into Spain.

Statutes for Jews (les Statuts des Juifs)

Anti-Semitic laws issued by the Vichy government in June 1941 known as Statuts des Juifs which defined who was Jewish in the eyes of the French State and excluded Jews from top positions in government, the military, and the professions of teaching, radio, the press, and theater.

Tract (le tract)

A pamphlet or leaflet used for political or religious purposes. During the WWII Occupation of France, the Resistance used tracts to keep citizens aware of the dangers of the Vichy Government’s collaboration with Germany.

Winter Vélodrome (le Vélodrome d’hiver)

An indoor bicycle arena in Paris where more than 13,000 Jews were kept after being rounded up on July 16 and 17, 1942. After being held for almost five days at the Vel d’hiv, the Jews were transported to Auschwitz. The Vel d’hiv round-up has become a symbol of French collaboration in the deportation and eventual extermination of Jews living in France. France annually commemorates the deportation of the Jews on July 16 at an official ceremony in the Place des Martyrs Juifs.

Vichy France (la France de Vichy)

After the fall of France and the occupation of three-fifths of the country, the government of France—under the leadership of Maréchal Pétain—moved to the city of Vichy. Although the town of Vichy was in the unoccupied part of France, the French government collaborated with Nazi antisemitism and deportations of Jews and other “undesirables.”

Yellow Star (L’étoile jaune)

Jews in France and other European countries were required by law to wear a yellow star embroidered with “Jew” to identify them as Jews.

Written Testimony #1

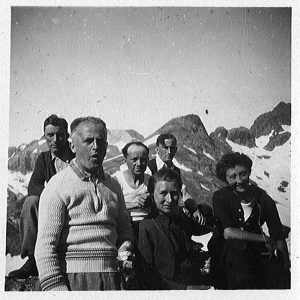

RENEE LISSE SACHS

March 13, 1940 – March 8, 2015

Note from Keith Sachs: Before WW II began, there were 16.5 million Jews living in Europe of which approximately 10% were children. By 1945, when the war ended, 6 million Jews were killed, and over one million of those who were killed were Jewish children. Only 5% of the Jewish children survived. Renee Lisse Sachs was one of those children who survived. Renee was born in Paris, at the very start of German occupation of France. After her mother was arrested, and life in Paris for Jewish people became dangerous, four-year-old Renee was sent to live with a relative in a small town in France where she learned to hide her identity and live as a Catholic.

Renee’s story shines a light on the toll war and the Holocaust took on the lives of surviving children. As a young child, she only knew that her mother and father were no longer caring for her and that it was dangerous to be herself, a Jewish girl. As with many hidden children, Renee’s experience of abandonment and fear shaped her life, especially as she struggled to make sense of why she survived when so many others did not. She became a teacher of foreign languages and then a Holocaust Educator. She wanted her students to understand the responsibility we all have to ensure that no future child should ever suffer as the hidden children suffered, and no parent should ever lose his child to the insanity of this world.

Renee documented her story in her testimony and presentations she made but passed away after reaching only one generation. What follows was largely written by her. I am only the messenger. I was her husband for 47 years. (K. Sachs, [2022])

This story is my story, told from the memory and viewpoint of a very young child who, from the age of four in 1944 until the end of WWII, was a hidden child. It’s a story about fear, separation from family, traveling on a long train ride to a place you know nothing about. It’s about guilt, seen through a child’s eyes and guilt, now seen through the eyes of a 68-year-old lady who is still trying to figure out why she survived while other children died (R. Sachs [2010]).

This is also about courage. The courage you get after tragedy. It’s about the will to live and to make each day a gift, which you have to constantly deserve.

It’s about the search for love that transcends hate and helps to heal the world.

Do not make me a hero or a victim. I had a terrible childhood both during and after the war, but I survived. And so, can each of you, no matter how difficult your problems are. You can also survive and both learn and teach that there are better ways to solve the world’s problems than war.

The world you are inheriting from us is a cruel and ugly world. There is hatred, war, famine, prejudice, racism and hunger. But it is also a beautiful world. Full of good compassionate people who can make a difference.

For every evil, there is hope. I am asking you to choose hope, not despair. Tolerance not evil.

You must speak out against evil when it appears. Speak out for those who cannot speak and stand for those who cannot stand. I cannot change the world alone and neither can you. But I can change people and people can change the world. Until, one day, after enough generations have heard the message, we will, at last, have peace for all peoples of the world.

I will tell you my story.

By the age of 15 and a half, I had spent more than half of my life as a hidden child in St. Pardoux de Riverie, or in a post war children home, Preventorium Vladik , in Brunoy, a town outside of Paris. I was born on 13 Mar 1940. Less than 100 days later, the French sued for peace. That is how my life began.

My mother, father and I lived in a two-room apartment in the 20th arrondissemont * of Paris. A neighborhood where the trade workers who had left Eastern Europe after WWI lived. There was a bedroom and one other room that served as a kitchen, living and dining room. There was a coal burning stove and a bin in which the coal was kept.

The units were very sparse. There were no toilets in the apartments. There was, instead, one toilet for the entire building. It was on the second floor. No apartment had a refrigerator or bathing facility. My mother went to the stores each day where she bought what she needed for the day. There was a box that hung outside the window. She would put food that needed to be kept cool, like butter or eggs, in that box. Once a week, we went to the public showers. During the week, we washed with a pan of water.

Before I became a hidden child at the age of four, I lived with my parents in this apartment. Though my mother and to some extent, my father, tried to make it a warm loving home, it never was one.

Their marriage was a marriage of survival – not love. My father was paid to marry my mother. That marriage enabled her to leave Poland. This was not uncommon. Her dowry was a sewing machine. They agreed that when the war ended, they could stay together or separate.

My mother and her sister left their parents and three of their five siblings when they came to France. Two brothers had left Poland earlier, in the late 1920s and early 1930, when exit visas were easier to obtain. One came to the U.S. and the other to France. My mother and her sister survived the war. Those who stayed in Poland did not.

My father never loved my mother. He told me that years later, but her brother, Martin, had paid him to marry her so she could leave Poland. This was apparently not uncommon. People were struggling to survive.

My father could be very harsh. He would yell at my mother and hit her. He had a life before my mother came to Paris and did not sleep at home every night. Yet, as cruel as he was to my mother, my father had a sense of duty to protect both her and me. Even now, I find it hard to understand.

Shortly after the French surrendered, the Germans implemented policies that required Jews to register with the police. They had to surrender their French ID card and would be issued one with the word Juif or “Jew” written on it. Jews also had to wear the yellow star. The penalties for noncompliance were severe.

But my parents and I were relatively safe and my father insisted that we did not need to register as Jews. My father was clever. He was only seventeen years old when he came to France. He came alone, in 1913, most likely to avoid being drafted into the Polish army. He was born in Warsaw during the last decade of the nineteenth century, but never told us about his past. My father could easily pass as an Aryan world. He had blond hair and blue eyes and, having been in France for over twenty-five years, he spoke French without a trace of a Polish accent. I was born with the same blonde hair and blue eyes. His most valuable possession, however, was a forged ID card with the name Claude Bernard. Monsieur Bernard was the name of a scientist, but it’s unlikely that they shared anything else. A false name and the street smarts to use it. With the tools, the family of Claude Bernard’s was not considered Jewish and did not register. My mother, however, was more Semitic looking, more typical of the Polish Jews. Her road would be more difficult.

I was four years old when I was first exposed to anti-Semitism. It happened when my mother and I were standing in a bread ration line. Food was rationed and you could only buy food on special days. It was our day and we were standing in line. The lady who was selling the bread looked at my mother and said, “We don’t serve Jews here.” (“Nous ne servons pas les Juifs ici.”) She said it as loudly as she could. What did she mean?

It was not long after that incident that my mother was reported to the police and arrested. The reward might have been no more than a pack of cigarettes.

My mother was alone, at home, when she was arrested. She was sent her Drancy, a detention camp north of Paris. Drancy was a terrible place and the majority of who were sent there, eventually found themselves in a box car, on a train going east to the camps.

But my father, posing as Claude Bernard, was able to obtain her release. He was a talented tailor. Maybe he made suits for the guards. Maybe he bribed them with money. It took a long time, but she was eventually released. She was not pardoned, just released. She could be arrested again. My father had told me that my mother was in the hospital and I began to think that if she was in a hospital, maybe I was responsible for her illness. This was the first of many times in my life when guilt followed by abandonment would haunt me. My mother’s sister, Tante (aunt) Renée took care of me along with my father during the time my mother was in Drancy. After my mother was released from Drancy, my family moved to another apartment and the decision was made that I would go into hiding. I was told it was for my safety, but I was only four years old and thought, again, that I had done something wrong. I was being punished. But I did not understand what I had done wrong. Where was I being sent?

My aunt, who had taken care of me while my mother was in Drancy, had already left Paris with her boyfriend. They lived in the village of St Pardoux de Riviere. St. Pardoux is several hundred miles southwest of Paris. There were no more than one thousand people in that village, so the Germans would not go there looking for Jews. So, the decision was made that I would go to St Pardoux and live with Tante Renee.

The day I was put on the train marked the end of my childhood. I was given a new name, a new religion in a new place. I was told that I must never tell anyone that I was Jewish or what my real name was. The new place to live was St Pardoux de Riverie, a small town six hundred miles southwest of Paris. There were no Jews in this town of no more than one thousand. Tante Renée had fled Paris and was there to meet me. She also had blonde hair and blue eyes. She had no children, only her male companion, Alexander. He was a Russian who had fled the war in Eastern Europe. The three of us would become a family.

Years later, Tante Renée told me about my first days with her. I was terrified to have been sent away by my parents. I was homesick, I cried and said that I wanted to go home. I sobbed for days about going back to my parents and Tante Renée told me that I would, as soon as I would see the red train (which of course did not exist). I was also very weak and had to be carried, either by Alexandre or in a poussette (baby carriage).

My aunt was very pretty and very smart. She spoke several languages, including German. So, the three of us became a family and over time, I begin to experience life as a “kid.” My aunt was younger and stronger than my mother. And Uncle Alexander was so kind. He would pick me up at school and we would play. He taught me how to read. His was a relationship I wish I had with my own father.

But my mother was always in my thoughts, but so was my aunt. One day I called Tante Renée, maman. It meant mama. Now, I could not tell who was mama and who was not. I was abandoning my own mother.

Despite all that was positive, there was danger around us and Tante Renée made it immediately clear that, although I was no longer in Paris, I could still be exposed as a Jew. I never understood what it meant to be a Jew growing up. And now, at the age of four or five years old, I had to forget being a Jew and become Catholic. I had to forget what I never knew or understood.

Tante Renée taught me how to make people think I was Catholic. I learned the Catholic prayers. She told me to always sit in the back of the church so I would know when to stand up and when to sit down. I was so afraid of the priest. If I saw him running toward the church, I would run and hide in the bushes. Sometimes I would wet myself: I could not control my fear.

Fear was my constant companion. If I made a mistake, my aunt, parents and I would be exposed as Jews. I was taught by the nuns that only Catholics went to heaven. Everyone else went to hell. How could I warn my parents? I must warn them. Otherwise, I would be responsible for hell becoming their destiny.

Strangely, however, there were moments when I actually found comfort in Catholicism. I longed for my parents, especially my mother and found comfort in the Virgin Mary. Everyone called her mother. Why not I? She was beautiful. She had flowers in her arms and she reached out to me with those flowers. I prayed to her quietly and asked her to take care of my parents. I spoke quietly lest someone hear me and know that I was living a lie and did not belong here. Maybe I did not belong anywhere.

During the two years (1944-1945) that I was a hidden child, I went to church and lived as a Catholic. I was told I had to do that to survive. The church taught me about Mary. I believed in Mary and prayed to her. But I don’t remember if I believed in G-d. When the war ended, I was six years old and I returned to my parents in Paris. I had found comfort when praying to Mary and I tried to continue praying to her after the war but stopped after a short time.

The three years I spent in Paris with my parents after the war were devoid of religion. No religion was practiced before and none after the war. I did not know that it meant to be a Jew before I went into hiding and still didn’t know when I returned. But praying to Mary seemed wrong, so I stopped.

We were Jews, secular Jews. My parents were never practicing Jews in either Poland or France. Despite their lack of belief, my parents were buried in a Jewish cemetery, by a Jewish burial society.

The two years while I was in hiding took its toll on everyone. My mother had always been a nervous person and my father was never a warm comforting man. He never loved her, but he had been offered money to marry her.

When I was nine years old, my mother suffered a stroke and I was, once again abandoned by my parents and sent away. I wanted to stay and help take care of my mother, but it did not matter what I wanted. I was sent to Preventoriam de Vladik in Brunoy. The Preventoriam was one of many children’s Jewish homes created after the war. A children’s home for children who needed medical attention after the war or had no parent who could take care of them. It was also a place where children could relearn what it meant to be a child.

The Preventoriam de Vladik practiced Judaism in a nontraditional way. Yiddishkeit. It was a celebration of being Jewish. The Jewish tradition, culture, character, or heritage. I found it very confusing. I had been told to never tell anyone you were Jewish.

Life in Brunoy wasn’t terrible. We didn’t starve. We were well taken care of and went to school. But it was pretty lonely. Nobody ever came to visit. I do remember that, vividly.

My mother died when I was eleven years old. No one told me. But she had a friend who wrote letters for her and sent them to me. Once the letters stopped coming, I knew she had died.

I had asked my teachers and the counselors at Brunoy, “What does it mean to be a Jew?” But no one had an answer, so I went in search of answers outside of Brunoy.

Across the street from the Preventoriam was a Yeshiva. The odd-looking men, with beards and unusual clothing had no contact with us, although occasionally they did come to take water from our well. Still, they were Jews. Maybe they could help me. So, I crossed the road and went into one of their buildings. I was looking for someone to talk to about “being Jewish.” I could not find anyone, but there were many books. I picked one up. I could not read the book, but it was a Jewish book. I took it home and put it under my pillow. At night, I would bring it out, hold it to my face and smell it. I wanted to feel Jewish. So, I hoped that it might come from touching this book. A book I could not read. But it didn’t.

I left Brunoy at fifteen and a half years old, no surer of my Jewishness and what it meant to be a Jew than when I came to live there six and a half years earlier. But I learned that the Jews were a people with a history of survival. For over 3500 years, they had survived despite the effort of armies much more powerful than they to destroy them. There must be some “divine intervention” that protects them. So, I promised that when I marry, I would raise my children as Jews. Millions had died in the name of Judaism. How could I forsake them?

At the age of 15 1/2, Renee had finished her education at Brunoy. Her father was a tailor. She was trained to be a seamstress. She dreamed of returning to Paris, to her father and Tante Renee.

“But my father had already been planning for my return. He wrote to his brother-in-law who had gone to America. My father signed away his parental rights and his brother-in-law agreed to sponsor me for a visa. In retrospect it probably was a better decision than remaining in France, but at the time, I viewed it as the third and perhaps final rejection of my young life. No one had asked me what I wanted. I did not want to go. I did not know this man or his wife. I did not understand the culture of this new country. I could not speak, read or write a word of English and now, I would be 6,000 miles from Paris.” (R. Sachs, YR *)

She had no choice, so she went, determined once more to survive, despite the feelings of abandonment. Because she spoke no English, she and was placed in the 7th grade. In seven years, she finished middle school, high school and college. She graduated, with honors, from West Chester College and earned a Masters at Michigan. She could now be financially free but not free of Survivor’s Guilt.

What of her family that she had left behind?

Her father, Tante Renee who had saved her when she was in hiding, and two cousins (brother and sister, one lived in Russia and one in France).

Renee did not return to France until ten years had passed, to see her father and Tante Renee. Visits with her father were difficult. He had sent her away too many times and was cruel to her mother. It was the war. Maybe he was never loved and didn’t know how to love.

We went four times. Two were with our children. She wanted our children to see the beauty of the country—not the ugly part. She also went to visit her mother’s grave. They had spent so little time together. Only five or six years before she died. But each time we went, she said:

“Everyone needs a mother to love her unconditionally and help her through life’s problem.” Each time we left Paris she would look out the window and wonder. “Who will visit me and put bring me flowers?”

One year I had a memorial plaque with her mother’s name on it. I showed it to her on her mother’s Yahrzeit: “Now you can visit you mom whenever you like and stay as long as you like.”

At the time, I did not understand what this would mean to her until she looked at me, with tears in her eyes and said:

“This is the nicest gift anyone has ever given to me.”

Then I understood what I had never fully understood. Renee found the answer to her survivor’s guilt. To teach. And she lived what she taught. In her eulogy, her daughter said, “Most of us treat people the way we are treated. mom treated people as they should be treated.”

Written Testimony #2

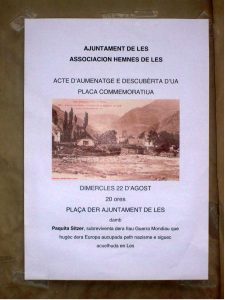

FRANÇOISE BIELINSKI, Better Known as PAQUITA SITZER

August 23, 1937 –

When I was born in Paris on August 23, 1937, my parents named me Françoise. The other members of my immediate family were my Polish born parents – Abraham Bielinski and Estera Markowitz and my older brother Reinhold. My parents met and married in Berlin in 1929. My brother, Rheinhold, was born in Berlin in 1932.

I am honored to share my family’s story of escaping Europe during the Holocaust. Being a child, I was a silent participant. The following sections have been divided by time and place. To add clarity, there are sections on what I was told happened, what I remember happened, and what I wish I had asked when my parents and brother were still alive.

Paris, 1937 – 1940

What I was told

My family moved to Paris from Berlin in 1933 after Hitler was elected to power. My father was a tailor by profession and had a small clothing factory. My brother went to school in Paris. In June 1940, Germany invaded Paris. My 7-year-old brother was in school. When they handed out gas masks for the children, he did not get one. When he asked the teacher where his mask was, the teacher said his mother should come and speak to her. When my mother came, the teacher explained that he was a foreigner and would not be getting a mask. This was the end of his school days in Paris.

In the late summer of 1940, my father was rounded up and arrested because he was a foreign resident in France. He was a legal resident but still a foreigner. He was sent to a concentration camp in Blois, France. This camp was under the supervision of the French Authorities. He managed to escape and made his way to the south of France which was not occupied by the Germans.

What I remember

My only memory of Paris was hearing sirens and running to a shelter in the basement. It was all dark and a baby was crying. Someone lit a candle. I have no other direct memories of the first three years of my life or the stressful situation my parents and brother experienced.

What I wish I had asked

What propelled my parents to move from Berlin to Paris when so many of their fellow Jews stayed?

How did they manage to relocate and create a new life?

How did my father escape from Blois?

Who helped him get to the south of France?

How did my mother manage without her husband and with 2 young children?

Pau/Lons, 1940 – 1942

What I was told

My father arrived in the city of Pau in the Pyrenees where he started to look for work. He was fortunate to be hired in a men’s shop owned by Victor Mesple-Somps. Victor was also a member of the French Resistance. Through Victor’s Resistance connections, my father made his way back to Paris and brought his family to Pau.

Once there, we were hosted, protected, and cared for during a month in the home of Madame Mesple-Somps and her daughter Henriette. They were Victor’s mother and sister. Afterwards, my father rented a house for the family in Lons on the outskirts of Pau. My brother stayed with Victor’s brother, Gaston, who was the mayor of Lons. At the time, Lons was a very rural area. We raised chickens in Lons. Our neighbors had never met anyone who was Jewish before and were surprised that we did not have horns. They were under the impression that Jewish people had horns.

For two years we lived in comfort. However, we were not really safe. Eventually we had to move on and leave France. Then next challenge for the family was to cross the Pyrenees into Spain.

Before leaving Lons, the chickens were slaughtered. My mother could not eat them as they were our family pets.

What I remember

Our neighbors would fight a lot. I could hear them yelling loudly and smashing glasses. I was surprised that they had so much glass to break.

I went to a kindergarten in Lons and cried when my mother left me there. My favorite after school snack was pain au chocolat (a small bread roll with chocolate in the middle). When the bread got hard my mother made pain perdu (French toast).

What I wish I had asked

What arrangements did my father have to make to return to Paris, pick up his family and take us to Pau in the South?

Was he able to communicate with my mother in advance or did he just show up to get us?

Did my parents agree on the course of action easily or were there a lot of discussions?

Why did my brother live elsewhere and not join our family immediately?

Why did we not give the chickens away?

Les, October 1942

What I was told

Once again Victor and his Resistance contacts came to our rescue. They arranged for our family to travel to Luchon, France. From there we were smuggled over the Pyrenees to Spain. The plan was that once in Spain, we would make our way to a port and leave Europe. My father had acquired entrance visas for Spain, as well as visas for a Central American country. The only item we were missing were exit visas from France. This is why we needed passeurs (smugglers) to help us hike over the mountains. My family arrived in Lerida (present day Lleida). We were stopped by Spanish police who wanted to arrest us. The guard who stopped us asked what my name was. My parents said it was Françoise. He said that the Spanish version of Françoise is Paquita. From this time, I have been known as Paquita. The policeman in Spain had a daughter and said I reminded him of his daughter. This is why they let us go and did not send us to Miranda de Ebros (a Spanish prisoner’s camp).

What I remember

The trip over the Pyrenees was long and I was tired. At some point, the passeurs carried me on their backs. I have no idea how long we walked. During the entire time I was told that we had to walk fast because the Germans were after us. To this day, I am a fast walker.

When the police stopped us, I remember my parents were crying and upset. This scared me.

What I wish I had asked

How did we get from Lons to Luchon?

How did my father pay for the visas and the passeurs (smugglers)?

Did he bribe the police to let us go?

What was the plan after arriving to Spain?

Barcelona and Vigo, October 1942 – February 1943

What I was told

My family spent some time in Barcelona waiting for a ship to take us to the Americas. We sailed out of Vigo, Spain in early 1943 and arrived in Venezuela in February.

What I remember

At some point during these months, I remember living in a pension (rooming house) with my family. I have a very visceral memory of opening a large floor to ceiling window onto a balcony. My parents quickly shut the window as there were police outside and we should not be seen.

What I wished I had asked

How were we moving from one place to the next?

What language were we using to communicate?

How were my parents earning money to pay for this?

If we had visas for a Central American country, how did we end up going to Venezuela?

What I subsequently learned

As refugees, we received assistance and monetary aid from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

Venezuela, February 1943

What I was told

On February 3, 1943, my family arrived in Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. A member of the Jewish community in Venezuela was on the ground and greeted the Jewish Refugees. He informed us that there was a Jewish community already established in Caracas. He let us know that the community members would help us get settled. We stayed in Puerto Cabello for one to two days and then made our way to Caracas.

What I remember

I remember that it was very hot all the time. The beds had mosquito netting over them – I had never seen this before.

What I wished I had asked

How did my parents learn to speak Spanish?

Who helped them enroll their children in school and get jobs?

How did they reconnect with family members that survived the war?

How were they informed of those who did not?

What was the biggest challenge in their new lives?

What came next

We settled into our new life. My father borrowed some money and started making suits. With the money from selling the suits, he was able to pay back the loan and make more suits. Eventually, my parents opened up a store and we were able to have a comfortable life.

My family was saddened to learn that our savior, Victor Mesple-Somps, did not survive the war. He was captured for his Resistance activities and murdered in Sachsenhausen Concentration camp in February 1945.

I was fortunate to attend both boarding school and college in the United States. When I graduated from Russell Sage College in 1958, I found work and settled in New York City. In 1960, I met and married my Polish-born Holocaust-survivor husband, Juan Sitzer. We went to live in Argentina and later relocated to Venezuela in 1963. One of the scars that the war and our escape left in me was the importance of having the right documents and passports. I knew that these could save our lives. Although I was no longer living in the United States, I wanted to give my children the safety of a United States passport. My daughter, Elizabeth, was born in New York in 1961. In the pre-jet times, friends and family thought I was crazy to travel from Argentina to New York to have a baby. I am happy that I have a U.S.-born daughter and that I was able to become a United States citizen, thanks to her sponsorship. When my son, Edward was born in 1963, I was not able to travel to the United States to have him. To this day he regrets not having a U.S. passport.

1992

I spent some time in Paris and in Pau, where I wanted to see some of the areas we had lived in during the first five years of my life. My parents were no longer alive, so I did not have any specific information regarding addresses. In Paris, I signed up for French lessons to reconnect with my mother tongue. In Pau, I attempted to reach out to relatives of Victor Mesple-Somps but did not find anyone who was interested in connecting. The rural area of Lons, where we had lived for almost two years, was now a suburb. I was surprised to see it was just three miles from the center of Pau.

2011

For her 50th birthday, my daughter and her husband traveled to Pau, France and then to the Pyrenees. They wanted to experience the area that was so instrumental to my family’s escape.

While they were there, I received a telephone call that would change the latter part of my life. A representative of the Venezuelan Friends of Yad Vashem (the Holocaust Museum in Israel) called to say there was a historian from Spain asking about me using my maiden name (Francoise Bielinski). I am a founding member of this organization in Venezuela. I told her that she can give him my email.

The historian and author, Josep Calvet, asked me if I was the Françoise Bielinski who was arrested in Les, Lleida, Spain in October of 1942 along with Abraham, Estera and Rheinhold Bielinski. Just hearing this question made my blood freeze in my veins. He went on to explain that his area of research is the Jews who escaped Europe via the Pyrenees. While doing research in the police records from the period in the town of Les, he found my family’s name. This was the first time I learned the name of the town where we had been arrested. Dr. Calvet contacted me several times over the next few months and I arranged to return to Les the following summer to celebrate my 75th birthday.

2012

Seventy years after my family’s daring escape via the Pyrenees Mountains, I returned with my children to spend a week in Les. Josep Calvet arranged for me to meet other senior citizens and see what they remembered. One woman remembered that her parents housed some of the “Polish people.” She remembered playing with children even though they could not speak the same language. It was surreal to be back in the area so many years later. As a result of this trip, I was able to connect with the wonderful people of Les. While I do not know the names of the people who asked the guard to let us go, I like to think that I met some of their descendants.

2015

I returned to the Pyrennes Mountains as a guest of the Government of Lleida. During this visit with my daughter and son-in-law, we were treated like VIPs. The purpose of the trip was to showcase the historical markers that the government has erected in many towns. These markers explain the areas where Jewish people escaped to freedom. This was a very emotional trip and I am very grateful to the entities that worked so hard to recuperate the memory of what happened and educate present and future generations.

2016

My daughter and I returned to the Pyrenees Mountains. This time we were again invited by the local government. The purpose of this invitation was to film a documentary. The Xarxa network from Barcelona rounded up two children of survivors and two grandchildren of survivors. I was the only person who actually crossed the Pyrenees Mountains. Filming an educational documentary and hearing the family story of the other people involved was moving and life affirming. There are no words to express my gratitude and admiration.

2018

“Le Dor Va Dor” From Generation to Generation. There was another family trip to the area in the summer of 2018. My daughter and son took their children to Les. They had the opportunity to hike through the Pyrenees Mountains. The same mountains that hosted my family’s escape to Freedom and Life in October 1942 are now a place the next generations can explore without fear. The miracle of the escape is evident. We are all very grateful to our savior, Victor Mesple-Somps and to the countless anonymous agents who made our lives possible. Along with my descendants, we are generations that would not be here if not for all these heroes.

References

Angelini, Eileen. (2022). Envisaging the interdisciplinary lessons of the holocaust via the examination of the WWII occupation of France: an instructor’s resource manual. Westfield, IN: Crane Center for Mass Atrocity Prevention.

Bracher, Nathan, ed. (Summer/Fall 1995). Contemporary French civilization: time to remember 19.2: Entire Issue.

Colman, Penny. (1998). Rosie the riveter: women working on the home front in World War II. New York: Yearling (a division of Penguin Random House).

Epstein, Eric Joseph and Philip Rosen. (1997) Dictionary of the holocaust: biography, geography, and terminology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Paxton, Robert O. (1972). Vichy France: old guard and new order, 1940-1944. NY: Columbia UP.

Rousso, Henry. (1990). Le syndrome de Vichy Paris: Seuil.

Weisberg, Richard H. (1996). Vichy law and the holocaust in France. NY: University Press.

Zucotti, Susan. (1993). The holocaust, the French, and the Jews. NY: Basic Books.

After the fall of France and the occupation of three-fifths of the country, the government of France—under the leadership of Maréchal Pétain—moved to the city of Vichy. Although the town of Vichy was in the unoccupied part of France, the French government collaborated with Nazi antisemitism and deportations of Jews and other “undesirables.” Wikipedia

The Vélodrome D'Hiver (Vel d'Hiv) was an indoor bicycle arena in Paris where more than 13,000 Jews were kept after being rounded up on July 16 and 17, 1942. After being held for almost five days at the Vel d’hiv, the Jews were transported to Auschwitz. The Vel d’hiv round-up has become a symbol of French collaboration in the deportation and eventual extermination of Jews living in France. France annually commemorates the deportation of the Jews on July 16 at an official ceremony in the Place des Martyrs Juifs. Holocaust Memorial Museum of San Antonio

Pro-Nazi Vichy French paramilitary unit of 30,000, formed in 1943 to support German Occupation and Marshall/Marechal Phillipe Pétain. It was active until August 15, 1944. EHRI

The Comité français de Libération nationale (French) or "French Committee of National Liberation", was a provisional government of Free France formed by the French generals Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle to provide united leadership, organize, and coordinate the campaign to liberate France from Nazi Germany during World War II…The committee directly challenged the legitimacy of the Vichy regime and unified all the French forces that fought against the Nazis and collaborators. The committee… evolved into the Provisional Government of the French Republic, under the premiership of Charles de Gaulle. Wikipedia

The years following its liberation when France underwent the painful process of remembering, commemorating, and coming to grips with this difficult period in its history. Oxford University