Aftereffects

An Israeli Perspective: Holocaust Dances

Ruth Eshel

Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom HaShoah) is commemorated in Israel annually on a fixed Hebrew calendar date that corresponds generally to mid-April. At 11:00 am, a two-minute siren is sounded. Israel comes to a standstill; the rest of the day is filled with memorial events throughout the country. As I grow older, a mother of children, and a grandmother, my comprehension of the horror intensifies. The emotion may be particularly evident in the Jewish state where Holocaust survivors live, countless families having first-hand experience of relatives murdered by the Nazi regime.

This article focuses on changes which have taken place in Israeli society relative to the Holocaust. Two questions inform the article: Which factors and turning points led to changes in attitudes towards the Holocaust? And how did those changes manifest themselves in dance?

Turning Points in Changing Attitudes Towards the Holocaust

The British Mandate (1920-1948)

When the Nazis seized power in Germany (1933), the flow of escaping Jews increased. Some immigrated to Eretz Israel, the Land of Israel, governed at the time by the British Mandate and called Palestine. My husband’s parents came from Berlin in this wave of immigration. His grandmother refused to join them. She saw herself as German, was not religious, was a respected social figure with many German friends and couldn’t believe anything bad would happen to her.

1938’s Crystal Night pogrom – Kristallnacht, “Night of Broken Glass”, – took place across Germany and Austria. As the numbers of fleeing Jews escalated, countries worldwide began closing their doors. In Mandate Palestine, the British imposed severe restrictions on continued immigration, as published in the White Paper, (May 1939). (Jewish immigration was to be limited to 75,000 over the next five years and then would depend on Arab consent. This policy also restricted Jews from buying Arab land. It acted as the governing policy during War World II to the 1948 British departure.) They were countered by Jewish resistance in the country that created the Ha’apalah, “illegal immigration,” with rickety ships loaded with refugees crossing the Mediterranean, making their way to Palestine, some drowning in the sea, most being seized by the British. Illegal immigrants were imprisoned in detention camps in Palestine, Cyprus, and more remote locations. The outbreak of World War II left European Jewry trapped under Nazi rule.

During World War II, Ausdruckstanz, “Expressionist dance,” was rejected by a world that saw it as affiliated with Nazism. But it flourished in Mandate Palestine. Dancers who fled Europe performed solo evenings, opened dance studios, and performed with their students. The war also brought about altered, light-hearted content. The growing fear of the future was reflected in dance as escapism.

The dimensions of the Holocaust were revealed when WWII ended in 1945. Survivors’ camps, also known as Displaced Persons camps, were established in the immediate aftermath of the war, most of their inhabitants being Jewish. Most demanded to immigrate to Eretz Israel despite the White Paper’s continued enforcement. Several Eretz-Israeli dancers were sent on missions to Germany to meet Holocaust survivors. Dancer Vera Goldman recalls: “They were so beaten down, in such extreme situations. And there we were, beautiful young people with curly hair, the young men especially with their dynamic strength” (Brin Ingber, 2011, 251-280). The emotional encounters between the young dancers and the survivors were a shock for both.

The United Nations’ decision on November 29, 1947 to partition the land into a Jewish and an Arab state was followed the next day with an invasion by seven Arab countries intent on destroying the newborn Jewish state. The Jews won that war in 1948. The State of Israel was created.

Attitude to Holocaust Survivors in Israel: The First Decade

In 1948 Israel was opened to additional Jewish refugees: large numbers from Islamic countries, European Holocaust survivors, and some immigrants from other countries. Among the Holocaust survivors were dance artists, including Yehudit Arnon, Shlomit Raz, Irene Getry and Clara Landau-Bondy. Shlomit Ratz came from Europe and settled in Kibbutz Ein Hamifratz (near Acre) in 1949. Born 1919 in Switzerland, Ratz and her family moved to Paris in 1935. Just before the outbreak of WWII she met a group of refugees from Germany and joined their experimental dance group headed by Heinz Finkel, a dancer/choreographer from Berlin. He lived in Paris undercover and died in the Holocaust, but Ratz managed to escape and return to Switzerland. Polish-born Irena Getry had studied classical ballet with Ruth Sorell in Dresden. During the war she hid in Holland and immigrated to Israel in 1949. Another arrival was Yugoslavian Klara Landau-Bondy, who had studied at the Budapest Opera School. Surviving Auschwitz, she returned to Yugoslavia where she worked with the Yugoslavian Army Dance Company before settling in Jerusalem in 1949 where she taught ballet.

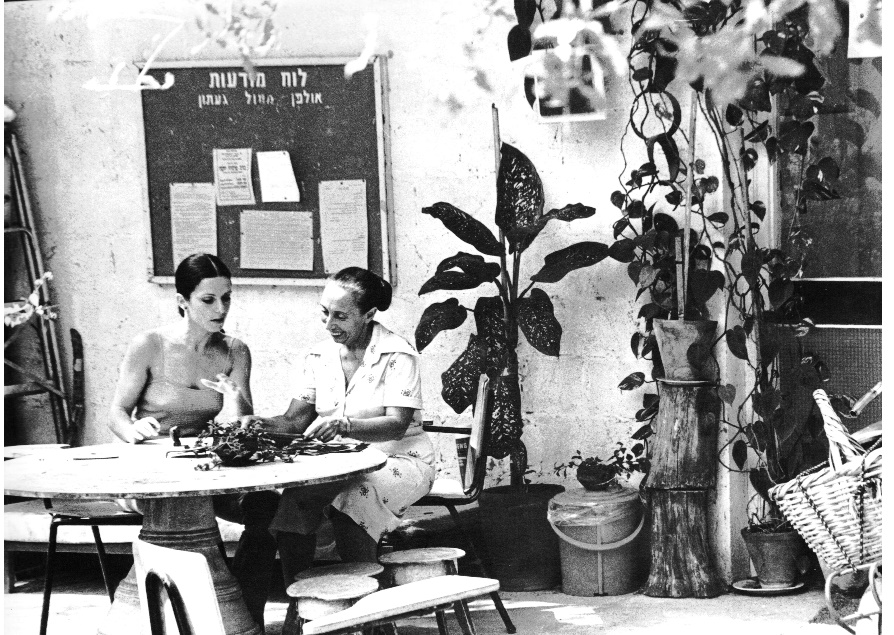

Perhaps the most influential of this group was Yehudit Arnon, born in 1926 in Komárno, Czechoslovakia. She was a fluent speaker of German with her father, and Hungarian with her mother. The Nazi invasion had cut short her studies in 1943 and she was sent to the Auschwitz extermination camp. She spoke to Dr. Josef Mengele when she disembarked from the train car; impressed by her fluent German he spared her by sending her to “work.” Two years later she was liberated. She went to Budapest, seeking to enroll at the Opera Ballet School, where she was told she was too old and should renounce the idea of becoming a dancer and choreographer. Arnon, undeterred, took classes with Irena Dykstein, a former student of Kurt Jooss, the ground-breaking German choreographer. Jooss’ masterpiece, The Green Table, is widely considered the greatest anti-war ballet ever produced. Jooss fled Germany in 1933 after refusing a Nazi request to dismiss the Jews from his dance company. As his student, Dykstein was influenced by Jooss’ principles of composition as applied to socially worthwhile subjects. Through Dykstein, Jooss’ concepts of socially relevant choreography were instilled in Arnon, who went on to implement these principles with the Hungarian branch of the socialist Zionist youth movement. As a counselor for Ha’shomer Ha’tzair, “The Young Guard”, Arnon made dances with hundreds of orphaned children whom the Young Guard took under its wing at the end of World War II. Arnon, along with her husband and their fellow counselors, needed to smuggle 100 children into Italy and then to Palestine. During the long journey, Arnon whiled away the time making dances out in the open. In 1947 the couple arrived with a group of children whom they delivered to Aliyat Hano’ar, “Youth Immigration”, which settled them in kibbutzim (plural of kibbutz) and youth villages which became both home and school. It was 1947 and the canons of the Israeli War of Independence were still thundering when Arnon arrived at Kibbutz Ga’aton in the Upper Galilee, near the border with Lebanon. Arnon would be the driving force behind establishing the world renown Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company in Israel. In 1998 she received the country’s prestigious Israel Prize.

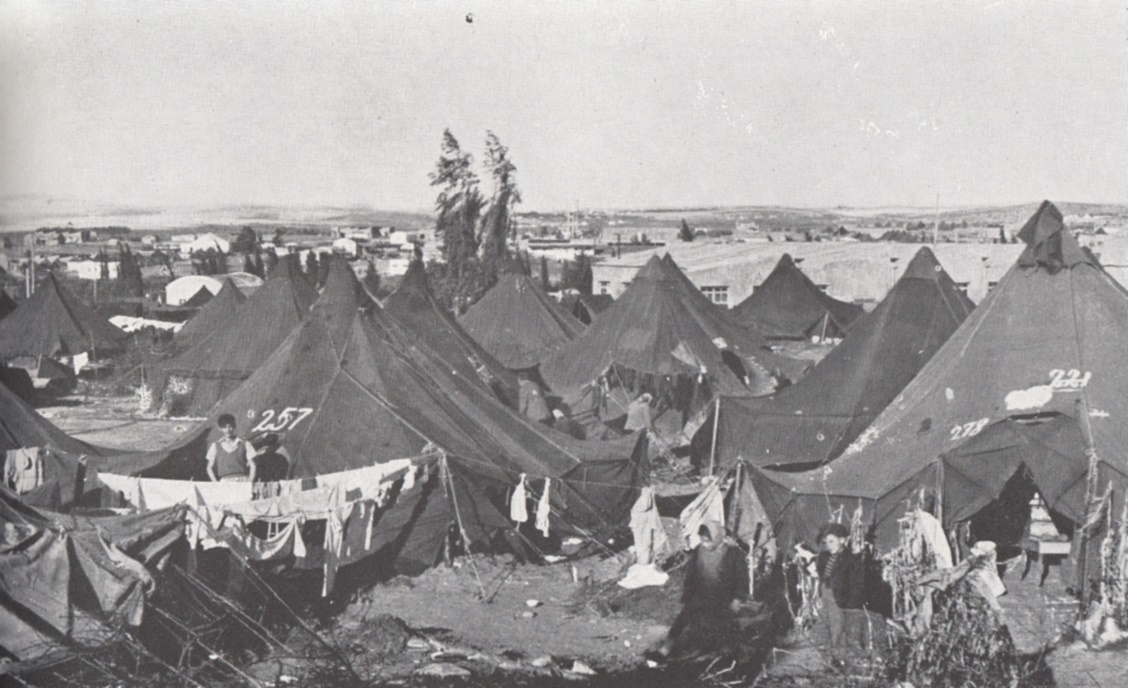

As a child, I remember the vast tent camps scattered across Israel to absorb the immigrants. Born in Haifa, I clearly remember these refugee camps at Haifa’s entrance and on Mt. Carmel’s peak. Beaten in winter by strong winds and torrential rain, the tents sank in the mud. Come summer, there was severe heat, mosquitoes, and flies. There I encountered Holocaust survivors marked by tattooed numbers. I do not remember children or the elderly among Holocaust survivors, who were often alone, painfully thin, nervous, their eyes pools of sorrow. My mother explained that they had been through terrible experiences, lost their dear ones, and some had gone crazy. It was better not to be in their company alone because they might behave strangely, she added. I also remember the daily early morning radio program seeking lost relatives. The news was the most important broadcasting program: the search for relatives was a close second.

Building new lives, Holocaust survivors sought to forget the past, which also helped maintain sanity. Mostly, they hid their personal stories. They married, had children (known as second generation survivors), but did not share their narratives, determined that not a grain of Holocaust suffering would cling to their young Israelis. Children did not insist on hearing their parents’ histories, not wanting to revive the horrors.

My friends and I used to wonder how European Jews went to the gas chambers like “lambs to slaughter“. It was the diametric opposite of the Zionist Israeli’s lauded image as the people who fought for their lives in our War of Independence. This misconception started to change in 1953 when Yad Vashem became Israel’s official Holocaust commemorative institution, located above Jerusalem’s Mount Herzl. Slowly information about the Holocaust began to disclose evidence of heroism that utterly discredited the stereotypical view of “lambs to slaughter.” In 1959, Menahem Begin, an Israeli politician and later the Prime Minister, (whose parents and brothers were murdered in the Holocaust) changed “Holocaust Day” to “Holocaust and Heroism Day.”

Turning Point

A turning point was the 1961 Adolf Eichmann trial. It cracked open the wall of silence around Holocaust experiences. After a protracted hunt, Nazi war criminal Eichmann was captured in Argentina and brought to Israel for trial. He was among the most senior of the SS responsible for implementing the Final Solution, a plan to exterminate all Jews. At the trial, survivors mounting the witness box described what they had concealed for 16-20 years. The trial was broadcast in entirety on the radio and followed by every household in Israel. During and after the trial, survivors began publishing autobiographies, which also helped change the population’s attitude toward the Holocaust.

Wars also played a part in changing the attitude towards the Holocaust. The Six-Day War (1967) between Israel and the neighboring states of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria ended with tremendous victory for Israel, but the menacing pre-war period reawakened the sense of existential threat and Holocaust trauma in many Israelis.

The 1973 Yom Kippur War which took Israel by surprise, further altered perspectives on the Holocaust. Yom Kippur is Judaism’s holiest day: even generally secular Israelis go with their families to synagogue to pray or simply listen to prayers. Streets are quiet, there is no public or private transport, no official broadcasts. Everything is closed. I was walking home from synagogue with my family and some neighbors. Suddenly the siren sounded. It took several moments to realize that this was the undulating siren used to warn of an enemy attack. Pictures of Israeli prisoners of war, of weakness and humiliation, were aired on TV for the first time. In the wake of the shock these evoked, a door was opened to the legitimacy of portraying other kinds of Israelis, including those whose identity encompassed the Holocaust.

Another turning point occurred in the early 1980s when the Education Ministry introduced the Roots project, initially to students at the junior high school level. It raised young Israelis’ interest in the Holocaust to which so many of their grandparents were connected, either directly or indirectly. The Roots project usually consists of building a family tree, recording family member’s experiences, personal interviews with family members, collecting photos and documents, documenting family history and historical objects and more. Over the years, the project has resulted in all family members being harnessed to help prepare the project, which frequently encouraged Holocaust survivors to break their silence. The Roots project remains integral to school syllabi.

Dance as a Reflection of Changing Attitudes toward the Holocaust

Until the 1980s, Israeli art about the Holocaust was limited. “The world of Auschwitz lies outside speech as it lies outside reason,” stated the Jewish philosopher and educator George Steiner (1967, 123). But where words are inadequate, the language of dance may be able to convey narratives and transmit emotional content.

Following are several examples demonstrating how the change in attitude towards the Holocaust manifested in dances presented and audience responses.

The first attempt was made by well-known dancer and ballet teacher Mia Arbatova. Earlier in her career, in view of the prevailing anti-Semitism in Russia, Mia Hirshwald took the non-Jewish surname Arbatova and began to wear a blond wig. Arbatova danced with the Riga Opera Ballet for six years. She married dancer Valentin Ziglovsky and joined him to dance in the Monte Carlo Ballet. When the winds of war began to blow, they preferred to distance themselves from Europe and moved to New York, where they worked with choreographer Michael Mordkin. In 1938 Arbatova immigrated to Palestine as a single woman. In 1945, she concluded her concert program by surprising the audience. Appearing on stage in the striped cloth of concentration camps, she neither danced, expressed pain nor despair but walked slowly, diagonally, across the stage, as though showing that while the Holocaust could not yet be danced, it should not be ignored. Haim Gamzo (1945), art critic at Haaretz newspaper, wrote that it was artless and tasteless to “represent a figure of the inferno.”

In 1953, a commemorative event marked a decade since the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, held in the evening at the open amphitheater near the museum of Kibbutz Lohamei HaGeta’ot (Ghetto Fighters), founded in 1949 by Holocaust survivors, partisans and ghetto fighters. Noa Eshkol, who invented the Eshkol/Wachman’s movement notation, performed for 50 minutes on several stages set at varying heights and scattered throughout the area. The piece was performed by Eshkol’s Movement Quartet and dozens of high school students to original music by Herbert Brün. A huge crowd, including my 11-year-old self, watched the minimalist symbolic choreography where Eshkol chose to eliminate a number of elements from the realistic narrative, compressing everything into abstract symbols. We simply accepted that a connection existed and blamed our non-comprehension on our own lack of depth in dance rather than express uncertainty or convey a negative reaction. No criticism of the work appeared in the media.

Provoking both positive and negative reactions on the moral appropriateness of dancing the Holocaust, Dreams (1962) was created by Anna Sokolow, a renown Jewish American dancer and choreographer. Splitting her time between Israel and the US, Sokolow founded the Lyric Theater in Tel Aviv in 1962, producing four programs. Each of Dreams’ eight scenes, with its clear concise but powerfully emotive structure, addressed a different aspect of the Holocaust. The Al Hamishmar newspaper’s Olya Zilberman wrote that Sokolow’s work “is on a subject that is painful, tragic and very complicated to turn into a work of art. Grave doubts awaken in us whether we should even venture into this subject precisely because of our need for abstract aesthetic symbols” (Zilberman, 1963). One scene presented a trio of girls forced by Nazis to provide sexual services in the camp. Their long hair loose, they moved from one position to the next, using positions reminiscent of whores waiting for their clients, thrusting pelvises out, turning their heads, gazing seductively, but when they opened their hands, flowers were revealed. In a lecture she gave in 1980 to dance students at the Jerusalem Rubin Music Academy, which I attended, Sokolow explained “that in the mirror we are prostitutes but within ourselves, we are flowers.”

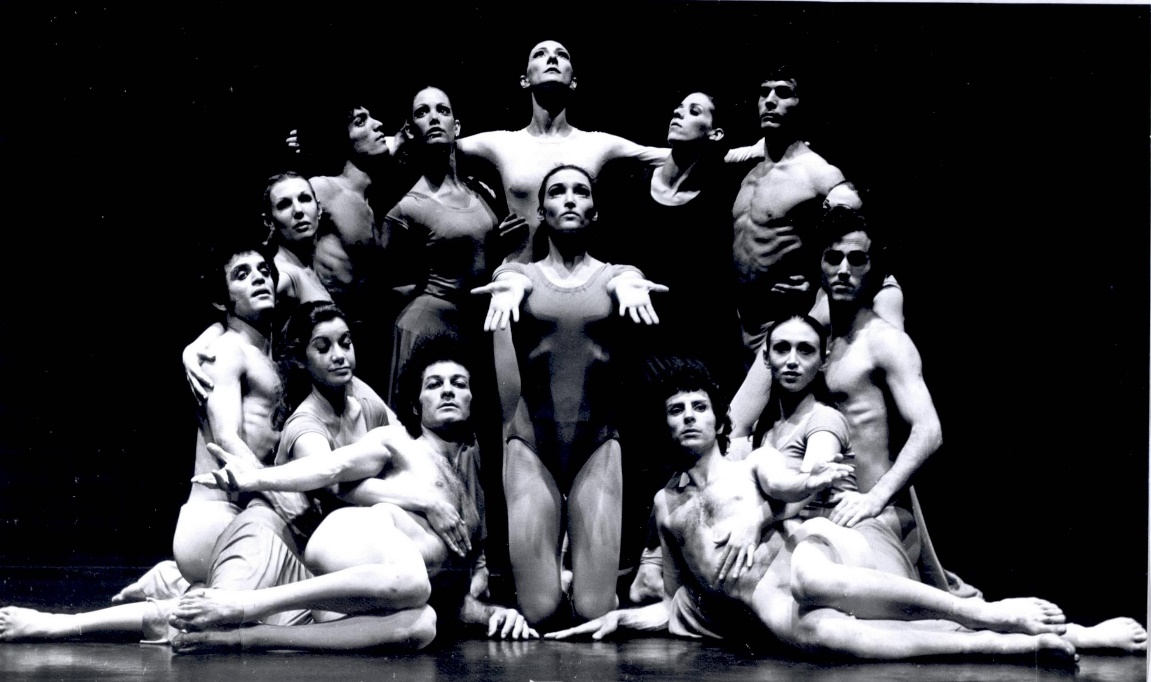

In 1971, a decade after the Eichmann trial, Stuttgart Ballet artistic director John Cranko premiered Song of My People – Forest People – Sea, referencing both the Holocaust and the resurrection of Israel. He set the piece on Israel’s Batsheva Dance Company, one of the foremost contemporary dance companies in the world. Ruth Ben Zvi and Dubi Zeltzer created the “musical set” and actress Hannah Meron recited accompanying poetry. Certain scenes in the work were accompanied by poems, including Uri Zvi Greenberg’s A Mound of Bodies in the Snow; Haim Nahman Bialik’s I Saw Light from the Darkness, Take Me Under Your Wing; and Until I Know by German Jewish poet Elsa Lasker Schüler. The final scene was set to a poem by a younger generation Israeli, Nathan Zach’s, I always want eyes to see the beauty of the world, and to praise this wondrous beauty that is without exception (Zach, 2009). Cranko was amazed by the upheaval the Jews had undergone in so few years: from near extermination to national independence. Choosing this epic subject was a serious commitment to his “Jewish blood.” Israeli choreographer Domy Reiter-Soffer later shared that Cranko confessed: “Do you know that I have Jewish blood in me, in fact a lot of Jewish blood in me? Too much Jewish blood in me to ignore that part of me, and the strangest thing about it is, here I am in Germany promoting and helping to build dance in the very country that helped to exterminate that part of me. In fact, if I was living in Stuttgart then I would have ended in some goddamn oven” (Percival 1983, 216). Batsheva rehearsal director Moshe Romano related that “The piece was a sequence of theatrical scenes and the movement material was both expressive and minimalist. . . . Choice of the subject caused disagreement among the dancers as did the use of text. Cranko succeeded in creating an up-to-the-minute, touching piece yet neither pathetic nor emotional” (Romano, 1991).

Since the premiere, 50 years have passed, yet the opening scene of Mound of Bodies is engraved in my memory today. Dancer Rahamim Ron came on the bare stage. A voice broke the silence: “And when my father was taken out to the mound of corpses, the German officer screamed: Ausziehen!” (Undress!) The dancer advanced several steps and halted. “And my father understood the verdict,” and the dancer bowed his head slowly, following orders, beginning to undress, garment after garment. “My father took off his shirt and his trousers, like someone discarding the materiality of this world,” and when he was naked and still standing, his white skin gleamed under the intense light. “He, the vicious one, inflicted a blow between his shoulders with his cold weapon, my father coughed and fell upon his face; as if prostrating himself before God; a deep bow to the bottom of life, and he never rose up again.” Then more and more dancers entered, stood, undressed, and fell one on top of the other so that the mound of white bodies grew, creating a cruel and horrifying beauty, a beauty that betrayed what happened. As actress Hannah Meron read the terrible words, her voice was hypnotic, emotionless. I remember that scene to this day. The audience did not breathe.

Some critics disagreed with the choice of subject. Miriam Bar wrote in Davar daily newspaper: “It’s hard to grasp how an artist of the stature of John Cranko does not sense that Auschwitz is not yet history, that one is already at liberty to search for its metaphors, stage and visual enactments, and so forth” (1971). She also wrote that one should not demonstrate death camps, and Jews who undress before entering the gas chamber, when the audience at Nahmani Hall in Tel Aviv included survivors of those camps. The critic continued, “it’s hard to accept the death camps of a generation ago in the stage images of dance.”

In 1975, for the 30th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Batsheva’s artistic director Kai Lotman asked Oshra Elkayam-Ronen to choreograph a dance on the Holocaust. Elkayam was a member of the first cast of Batsheva and stood out as a talented choreographer with an individual voice who had already created two dances for the company between 1964-1966. Following her husband, an air force pilot, to his new base at the North of Israel, she left the company in 1966. Three years later, his plane was shot down in Egypt during the War of Attrition that involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) and their allies from 1967 to 1970.

About Lotman’s proposal Elkayam told me: “I told Kai that I’d been waiting a long time for this commission, but why on such a subject? I begged to be let off, but he insisted.” She spoke of the process:

The rehearsals were very hard. It took a while to get the dancers, who were used to big movements and energetic physicality, to fold their wings and feel right about simple movements that were born of an inner, personal feeling. Some of the dancers were against this in the beginning, each for his or her own reasons, but gradually, as each agreed to try, and slowly, slowly, without even being aware of it, they were absorbed into the “experience” of this horror. There were those who had to leave in the middle of the rehearsal from time to time and go outside so they could cry in private (Elkayam, 1994).

Elkayam’s Eclipse of Lights opened with a semi-transparent curtain through which the audience saw movement emulating a frantic mass pointlessly running about in an extermination camp encircled by an electrified fence. It had the feeling of a remembered dream event, beyond belief, that is and is not. Reviews raved. In the journal Musag, “Notion”, Leah Dovev compared John Cranko’s dance, which she thought did not work, to Elkayam’s in a review titled “The Ghastly Possibility Is Possible”:

A truly impressive premiere, not by virtue of Uri Zvi Greenberg’s words, but on its own. A ballet about a concentration camp, (and who in his right mind could even imagine such a pairing?), that can give one the shivers. The very fact that it has happened, that it is possible, perhaps atones for the awful banality inherent in any such experiment. Somehow, what Greenberg, Meron, the acclaimed Cranko and unparalleled soloists could not do, Elkayam did, with a team that worked as an anonymous group, and simple choreography. The success of Eclipse of Lights has no bearing on the question of mounting a ballet on the subject of electrified fences and people running around, trapped. […] There is something terrible in that, to see and to know that to create such a ballet is at all possible, to work on it, think about it in terms of tempo, matching the number of steps, the angle of the spotlights, and applause at the end, to fail with it, or succeed (Dovev, 1975).

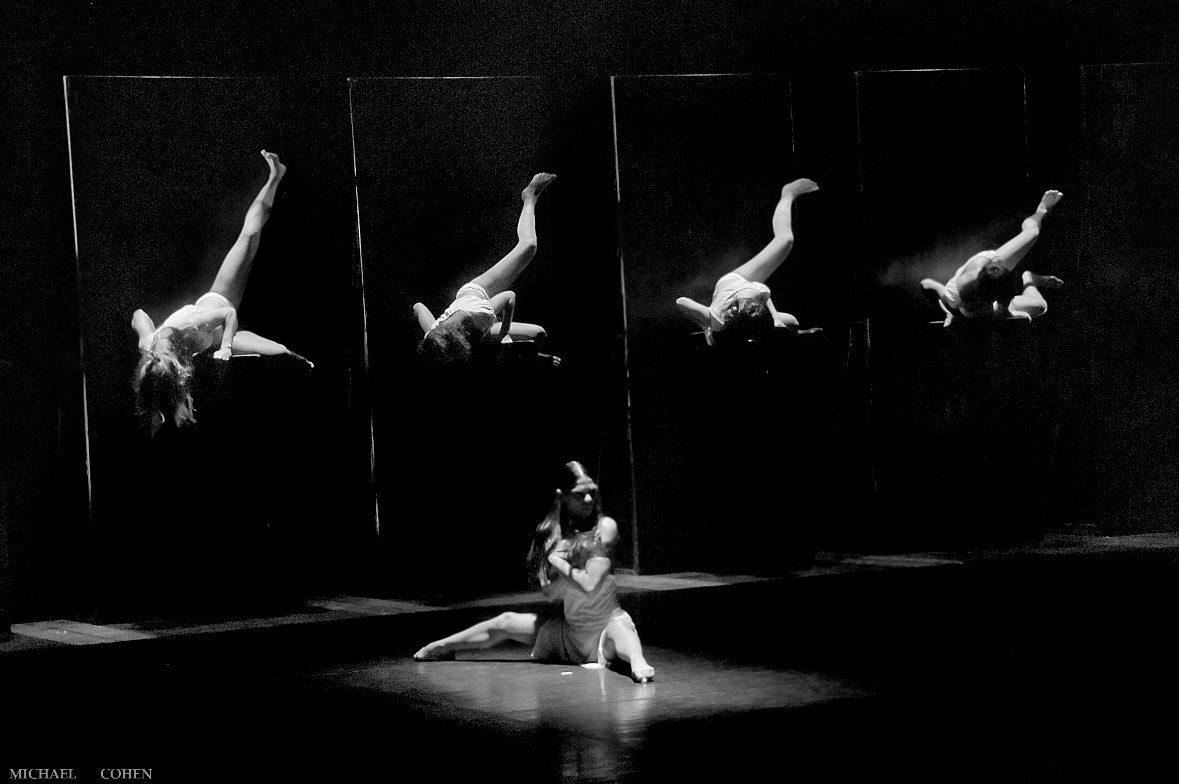

A different attitude to the Holocaust than any of the above is found in the dance Zichron Dvarim, 1994, Aide Mémoire, by Rami Be’er. It did not illuminate awfulness: on the contrary, it went in the direction of a poetic visual beauty that recalled a requiem, its connection to the Holocaust floating up like an echo from the past, permitting a moment of respite to the viewer who finds it hard to confront the subject directly.

The son of Holocaust survivors and a kibbutz member, many of whose friends had come from a similar background, Rami Be’er, artistic director of the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, kept silent for many years. But as the generation of survivors dwindled, the importance of preserving those memories increased, leading Be’er to produce Aide Mémoire.

Movement intersected with impressive stage architecture: huge, horizontal copper oblongs at the rear of the stage, set at equal distances and recalling windowless cattle-cars in which the Jews were transferred to the Death Camps. One could climb the sides, progress single file to the “roof,” descend, wriggle between the cracks, disappear and reappear between them. The copper oblongs also became a huge musical instrument that one could strike to evoke a tempo. Thus, the architecture was directly linked to the subject, yet at the same time offered compositional and movement solutions that were artistically solid even without relating to content.

The musical collage consisted of solo piano, song, the sound of moving trains, bells and drumming on the copper oblongs. But it was the orders bellowed by a man in German and Hungarian, the languages of the lands from which his parents came, and even in English (indicating the importance to the choreographer that they be understood) that caused the dread. The words were Raus, “Out! Get Out”, to those alighting from the carriages or driven from their hiding places, and Schnell, “Hurry”, to the skeletal creatures stumbling along. These were the commands played over the loudspeakers in the extermination camps or at the railroad stations.

Rami Be’er contended: “The piece sends a voice to the past, to the Holocaust, a voice that warns us, and places the responsibility on us as a society, to learn from it. It carries a message against violence, against racism” (2014). Asked how his parents reacted when watching the work, he said, “They, and all their friends, the founders of the kibbutz, were very excited. They came out [of the theater] in tears, saying it touched them most deeply. Some of them came back again and again to watch the work.”

In the first two decades of the 2000s, a number of dance works on the subject of the Holocaust were created. Among the most prominent are dances by Tamar Mielnik who was born in Belgium. Her survivor parents died young and her two brothers had been murdered in Treblinka. Miriam Lounsky-Katz, one of the founders of the Brussels Yiddish Theater, adopted her, and her career as a singer and actress started there. In 1971, at 24, she immigrated to Israel and studied dance at the Rubin Academy in Jerusalem and in 1985 established Jerusalem Dance Theatre. Mielnik’s work, When I Grow Up to Be Little (2007) was based on the writings of Janusz Korczak. Korczak, a Polish Jew, ran an orphanage in Warsaw. At various points during World War II, Korczak was offered sanctuary, but each time he decided instead to stay with the children in his care. Korczak chose to accompany his Jewish orphans to the gas chambers of the Treblinka extermination camp, holding their hands. Mielnik told me that nobody held her brothers’ hands when they were murdered in the Holocaust.

In 2019, Nadia Timofeyeva, artistic director of the Jerusalem Ballet created the ballet Memento. Nadia is the daughter Nina Timofeyeva, a former Bolshoi ballerina who immigrated to Israel in 1991 with her daughter Nadia in the second wave of immigration of Jews from the former USSR, known as the post-Soviet aliyah. (The post-Soviet aliyah began en masse in the late 1980s when the government of Mikhail Gorbachev opened the borders of the USSR and allowed Jews to leave the country for Israel.) Memento tells the heroic and tragic story of ballerina Francesca Mann (née Lola Horowitz) who was murdered on Oct 23, 1943 in a changing room before the “showers” of gas at Auschwitz-Birkenau Crematorium I. She became a legend of resistance, her story told and retold. Mann, a known dancer in Warsaw before the Nazi period, was leered at by the cruel SS Sergeant Josef Schillinger who demanded she dance for him. Though naked, she pranced towards him, grabbed his gun, snaked her body around him and shot him before being killed by his accomplices. In an interview with Sarah Hershenson (2019) of the Jerusalem Post Timofeyeva said: “Even though I am apolitical and live my life in a ‘Ballet Bubble,’ I know everything can happen again. We must be active, not passive.” Timofeyeva has confidence audiences will consider the anti-Semitism rampant in the world then and now. (Ibid).

Today more and more people belonging to the third generation of Holocaust survivors feel the responsibility to tell what happened. Some of them remember a story from their grandparents, others find a family document that illuminates a secret story when there is a legitimacy and openness to engage in the subject. Timofeyeva chose to end Memento with the song of Hatikva, “The Hope”, which is Israel’s national anthem. For Timofeyeva who was not born in Israel, and immigrated from the former Soviet Union, Israel represents the hope that there will never again be a situation where Jews will not be able to defend themselves.

References

Bar, M. (1971, October 18). “Three Premiers at Batsheva,” Davar.

Be’er, R. (2014, April 18). Cited in Maya Cohen’s “To Dance the Holocaust,” Israel HaYom.

Brin-Ingber, J. (2011). “Vilified or Glorified? Views of the Jewish Body in 1947.” In Seeing Israeli and Jewish Dance, edited by Judith Brin Ingber, 251-280. Wayne State University Press.

Elkayam-Ronen, O. (1994, April). Interview with Ruth Eshel.

Dovev, L. (1975, April). “Batsheva Dance at the 75’ Israel Festival- The Ghastly Possibility Is Possible,” Musag.

Gamzu, H. (1945, June,8). Haaretz.

Hershenson, S. (2019, August 25). “Memento by Jerusalem Ballet.” Jerusalem Post.

Kaes, A. (1992). “Holocaust and the End of History: Postmodern Historiography in the Cinema.” In Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the “Final Solution,” edited by Saul Friedlander, 206-22. Harvard University Press.

Percival, J. (1983). Theatre in My Blood: A Biography of John Cranko. Franklin Watts.

Steiner, G. (1967). Language and Silence: Essays on Language, Literature, and the Inhuman. Athenaeum.

Romano, M. (1991). Interview with Ruth Eshel.

Zach, N. (2009). “I Always Want Eyes.” Translated by Saul Feinberg. In Life’s Daily Blessings: Inspiring Reflections on and Joy for Every Day Based on Jewish Wisdom, edited by Kerry M. Olitzki. Jewish Lights Publishing.

Zilberman, O. (1963, July,13). “Anna Sokolow’s Lyric theater.” Al Hamishmar.

"Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom HaShoah) on which we remember the Holocaust and honor the memory of those who perished.” URJ

The term Eretz Israel, or Eretz Yisrael refers to the land of the children of Israel. Use of the term Eretz Israel began in the bible (II Kings 5:2) from the time the Israelite tribes began to live in the land. The land - or parts of it -had many other names, including Canaan, Yehuda, Judea, The Holy Land, Terra Sancta and Palestine. It is also referred to as the Promised Land based on God's often-repeated promise to Abraham and his descendants. Rossington Center for Education and Dialogue

The name given to illegal immigration by Jews, most of whom were refugees escaping from Nazi Germany, and later Holocaust survivors, to Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and 1948, in violation of the restrictions laid out in the British White Paper of 1939. With the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948, Jewish displaced persons and refugees from Europe began streaming into the new sovereign state. Wikipedia

Josef Mengele, also known as the Angel of Death, was a German SS officer and physician. He conducted inhuman medical experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz. He was the most prominent of a group of Nazi doctors who conducted experiments that often caused great harm or death to the prisoners. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

“The Young Guard” is a socialist Zionist youth movement founded in 1913. Wikipedia

“Youth Immigration” (Hebrew) is a Jewish organization that rescued thousands of Jewish children from the Nazis during the Third Reich. Youth Aliyah arranged for their resettlement in

Palestine (Eretz Israel) in kibbutzim and youth villages that became both home and school. Wikipedia

The phrase was taken to mean that Jews had not tried to save their own lives, and consequently were partly responsible for their own suffering and death. This myth, which has become less prominent over time, is frequently criticized by historians, theologians, and survivors as a form of victim blaming. Wikipedia / Wikipedia

(Hebrew, Milẖemet Yom HaKipurim), also known as the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, was fought from October 6 to 25, 1973, by a coalition of Arab States, Egypt and Syria, against Israel. Wikipedia

A well-known doctor and author who ran a Jewish orphanage in Warsaw from 1911 to 1942. Korczak and his staff stayed with their children even as German authorities deported them all to their deaths at Treblinka in August 1942. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The immigration of Jews from the diaspora to the Land of Israel historically, which today includes the modern State of Israel. Wikipedia