Settings

Terezín and ‘The Last Cyclist’

Naomi Patz

Film Trailer: “The Last Cyclist”

What We Need to Know about Terezin

Terezín (Theresienstadt, in German), was a Nazi transit camp and ghetto labor camp forty miles from Prague in what is now the Czech Republic. It was built by the Hapsburg monarchy as a walled garrison town and fortress in the 18th century. Early in the Second World War, the Nazis evicted Terezín’s civilian population and forced the camp’s first transports of Jews to reconfigure the garrison into a prison. In 1944, to reinforce the façade that Terezin was a “model camp for Jewish people,” the Nazis spent more than six months meticulously camouflaging the ghetto for inspection by observers from the International Red Cross.

Terezín was a work camp and transit point, not a site of mass murder like the six Nazi death camps: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chelmno, Treblinka, Majdanek, Sobibor, and Belzec. Even so, through starvation and disease, the death rate in Terezín was comparable to that of Buchenwald and Dachau, two notoriously deadly concentration camps in Germany. More than 144,000 Jews were imprisoned in Terezín between 1941- 1945. Only fifteen percent of them survived the Holocaust.

Terezín was a dreadful place. At its most crowded, some 60,000 prisoners were crammed into an area approximately five by eight city blocks which was meant to hold 6,000 people. Escape and hiding were virtually impossible in the context of Nazi practices and Terezín’s design, location, and geography.

Families were divided. There were separate barracks for men, women, and children. Approximately sixty people slept crowded into three tiers of bunks in each poorly heated dormitory room. The prisoners had no privacy, no modesty, no personal space. Three or four hundred people, many of them suffering from dysentery and other stomach ailments, shared a single toilet and often the toilets were backed up and overflowing. Their food ration consisted mainly of bread, potatoes, cabbage, and turnips with virtually no protein in the diet. People lined up for these bare-subsistence meals holding their personal plate, spoon, and mug – vital necessities – and stood to eat whatever was ladled out to them.

The situation in this and other camps was particularly desperate for the elderly. To have enough food to keep the children and workers alive, the Council severely limited the already inadequate rations for those too old to work. As a result, many of the elderly died in Terezín of starvation.

The Terezín Jewish Council of Elders (also known as the Jewish Self-Administration) was a group of prisoners compelled by the Nazis to run Terezín’s internal affairs. Adolf Eichmann himself chose the heads of the Council. The Council organized the work (Nazi-forced labor) that was done by prisoners in the kitchens, hospitals, and schools for children.

The Gestapo forced the Council to compile the deportation lists to what we now know were death camps. “They had to play God,” stated Edgar Krasa, a survivor who worked as a cook in Terezín. Although most of the prisoners had no notion of where the “trains to nowhere” were taking the inmates whose names were posted on the lists, everyone was certain that no matter how bad conditions were in Terezín, things would be much worse in “the East.”

Despite the horrific conditions in the camp, every inmate – including youngsters over the age of fifteen – was forced to work long hours every day of the week. Some were assigned to assembly lines splitting mica or sewing military uniforms or producing other “essentials” for the German war effort. Many worked as draftsmen, designers, artists, and accountants preparing reports for the SS, who required everything under their control to be recorded with graphs, detailed statistics, surveys, and lavishly illustrated documents. Each camp inmate was registered in at least seventeen files.

The work was fraught with tension because a mistake as simple as a typographical or clerical error could lead to drastic punishment, even death. Yet the artists who worked there endangered their lives to steal paper, pencil stubs, colored chalks, and other art supplies to document in secret the horrors and atrocities in the camp, and to provide supplies for the clandestine children’s art classes. Other prisoners did the wide range of jobs necessary to keep the camp functioning. In this environment, what would under normal conditions be insignificant assumed overwhelming importance: breaking a shoelace or losing a spoon was nearly catastrophic. In this way, Terezín was like the other Nazi camps.

Terezin Statistics

Terezín is located about 40 miles from Prague. It was built in the mid-18th century as a Hapsburg garrison town meant for 6,000 people.

Between 1941 and 1945, more than 144,000 Jews were imprisoned in Terezín. Nazi records show that 33,450 of them died in Terezín. Only 15% of these prisoners survived the Holocaust.

Some 88,000 of the Jews who passed through Terezín were sent to the death camps in the East, most of them to Auschwitz. Only 3,000 of them survived.

Approximately 10,500 children 15 years and younger were among the Jews imprisoned in Terezín. According to Nazi records, 400 of the children died there.

More than 7,500 children were sent from Terezín on transports to “the East” (to Auschwitz, Treblinka and the other death camps). Only 245 of them were alive at the end of the war.

When Terezín was liberated by the Russians in May 1945, there were about 2,000 children under 15 in the camp, the majority of whom had just arrived on “evacuation” transports from the death camps being liquidated by the retreating Nazis.

Some of the children who were alive at liberation died of disease and the effects of malnourishment within the first days, weeks, and months after the war.

(Statistics provided by Vojtech Blodig, Vice-Director, Terezín Memorial – Ghetto Museum)

The Nazi “Show” Camp

Terezín was unique in the Nazi concentration camp system. It was a most cynical example of the deceptions that Nazis perpetrated on the West. Among the highly cultured Western and Central European Jews whom the Nazis imprisoned in Terezín were many internationally known writers, actors and singers, composers, musicians, scholars, philosophers, scientists, and visual artists. Their sudden disappearance would have created a major public relations problem for the Nazis. To address this, the Nazis created the fiction that Terezín was a “model ghetto.” Terezín prisoners were unusual in that they did not wear uniforms; they wore their own clothing. The Nazis misled the wealthy, elderly German and Austrian Jews whom they were sending to the camp into believing they were going to a spa town where they could sit out the war in safety. So convinced were these deportees that this would be true that they packed fancy dress clothes and some, on arrival, even requested accommodations with a view of the (promised but non existent) lake.

The SS even acceded to the Danish government’s pressure on the Germans to allow a visit to Terezín by the International Red Cross in June 1944. This hoax was a particularly egregious example of the Nazis’ strenuous and persistent efforts at deception. Having allowed the inmates cultural and artistic activities, including an accomplished volunteer choir, the SS perverted those activities to serve their own purposes.

The SS undertook a vast, months-long “beautification” campaign in advance of the Red Cross visit. The campaign involved a physical upgrading of the facilities that the delegation would be taken to see – among other “beautifications,” removing the third tier of bunks on the ground floor of the barracks to be visited, the creation of cafes, a soccer match, a bandstand, a merry-go-round, a performance of the Verdi Requiem, and even the printing of fake currency, as well as the deportation of 7,503 people, largely the sick and elderly, to reduce overcrowding and increase the “healthy appearance” of the prisoners who would become performers in this travesty.

The members of the Red Cross delegation were so thoroughly deceived that they decided not to go on to inspect the ‘family camp’ at Auschwitz-Birkenau, which had been part of their original plan. Whether or not the Nazis would have allowed such a visit, given that Auschwitz-Birkenau was one of the death camps, is another matter. And yet, a member of that delegation, Swiss doctor Maurice Rossel, later claimed that he did visit Auschwitz and had tea with the director of the camp, but that he did not see any other part of Auschwitz itself or Birkenau. (Source: an interview with him by Claude Lanzmann in Lanzmann’s 1999 film, “A Visitor from the Living.”)

The Red Cross visit was followed by the creation of a Nazi propaganda film. Kurt Gerron, a brilliant filmmaker from Berlin, was forced to be its director. The film came to be called “The Führer Gives the Jews a Town.” It presented a totally fraudulent portrait of the camp and hid its deplorable conditions. Gerron and virtually everyone else involved in producing, directing, filming, and acting in the movie were deported immediately afterward to Auschwitz. Only a fragment of the film remains. It is available to visitors to the Ghetto Museum at Terezín and is also accessible at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. See: Theresienstadt: A Documentary Film 1944.

Apart from propaganda purposes, the SS didn’t care what went on in the camp so long as it didn’t involve overt acts of subversion or sabotage:

…the supreme irony of Terezín is that within its walls it was artistically the freest place in occupied Europe. Elsewhere Jewish music was forbidden, so-called “degenerate music” and jazz were banned, but in Terezín they played Mendelssohn, Offenbach and the works of the composers incarcerated in the ghetto. Most of these works would have failed the degeneracy test as well as the racial one. (Broughton, 1993)

A great many inmates contributed in one way or another to the extraordinary flourishing of culture in this most unlikely of places. In the bizarre environment of the concentration camp, in the constant presence of death, they managed to have “an artistic and intellectual life so fierce, so determined, so vibrant, so fertile as to be almost unimaginable (DeSilva, 1996, p. xxxiv) There was a lending library at Terezín with more than 60,000 books, brought by prisoners as part of their precious permitted kilos of luggage when they were deported.

A Czech theater director who was deported to Terezín in August 1943 and survived the war, expressed it this way:

If Terezín was not hell itself, like Auschwitz, it was the anteroom to hell. But culture was still possible, and for many this…was the final assurance. We are human beings, and we remain human beings, they were saying in this way, despite everything! And if we must perish, the sacrifice must not have been made in vain. We must give it some meaning! (Frýd, 1965, p. 217)

According to another survivor, “… the only means to survive, if at all, was for the spirit to transcend the pain of the body.” Heroism was “in the will to create, to paint, to write, to perform and to compose in hell.” (Tuma, 1976, p. 15)

As Jana Šedová wrote in 1965,

Hardly anywhere in the world was there such a grateful audience as in the attics of Terezín. Hardly a single actor anywhere else has ever been rewarded for his endeavors by such love from his public. … a great hunger for culture in a place where there was not even enough bread to eat. (p. 221)

Cultural and educational activities, secret archives, hidden synagogues, and clandestine religious observances reaffirmed a sense of Jewish community, history, and civilization in the face of physical and spiritual degradation – and, ultimately annihilation, although that was unimaginable to the Jews in Terezín. They refused to allow their spirit to be broken even under profoundly dehumanizing circumstances. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2018).

Entertainment in a Concentration Camp?!

It defies our understanding to imagine concentration camp inmates singing, playing classical music, and dancing on makeshift stages or in crowded barracks while cattle cars transported fellow inmates toward Auschwitz. The grotesquerie of such events suggests frivolity and even sacrilege. If people could act in plays and create art while facing death, that would have to mean that life in the camps could not have been so desperate. But the inmates knew that the camps were evil. And we know that they were very evil. And we now know that people sang and danced despite and because of the Nazi hell and the murderous ‘Final Solution.’ (Rovit, 1999, p. 4)

An amazing number of prisoners produced an incredible range of cultural activities. Inmates performed classical and jazz favorites and wrote their own new music. They mounted operas (Smetana’s being far and away the favorite). They presented major choral works, including the Verdi Requiem which featured more than one hundred singers, all of whom had to learn the score by heart since only one copy of the music had been brought to the camp. More than 500 prisoners presented over 2,400 lectures in their various fields of interest. (Makarova, et al., 2000)

Many playwrights, actors, singers, directors, stage, and costume designers were among the camp inmates. They mounted well-known plays by Chekhov, Gogol, Cocteau, Molière, as well as original cabarets and skits satirizing life in the concentration camp. Productions involved careful preparation and high standards were maintained.

The staging of every single play, cabaret, opera, solo performance, and concert was accompanied by immense difficulties resulting from the camp’s conditions. At every turn it was necessary to get over new obstacles: the acquiring of dramatic texts, night rehearsals, seeking for convenient rooms for staging and rehearsing. The theatre ensembles used to rehearse in various garrets, cellars, in cold, dark lofts without light. František Zelenka, who had been an architect and a renowned scenographer in Prague, managed to create even in the environment and conditions of Terezín, many original theatrical scenes as well as costumes full of imagination, metaphor, and poetry. It was unbelievable how much he was able to get out of the minimum material at his disposal. (Pechová, 1973, p. 34)

Zelenka worked wonders with bedsheets, torn pieces of paper, bits of clothing and whatever other scraps were available to him. In his fifteen months in Terezín, Zelenka designed sets and costumes for thirty productions including The Last Cyclist, which we examine in detail, as well as the set for the children’s opera Brundibar. František Zelenka was murdered in Auschwitz in October 1944.

By unspoken agreement, no tragedies were staged. Plots were satiric and upbeat, although the reality of their situation often crept in simply by being the very opposite of what was being presented. For example, one of the skits written in the camp praises the amazing Terezín weight loss diet that has everyone absolutely emaciated. Another gushes with excitement about a pet flea. The prisoners didn’t need to be reminded of the dangers, fears, and horrific living conditions in Terezín. They wanted to laugh, to be entertained, to forget reality, if only for an hour (Peschel, 2014).

Holocaust humor “focused attention on what was wrong and sparked resistance to it…It created solidarity in those laughing together at the oppressors…[and] it helped the oppressed get through their suffering without going insane” (Morreall, 1997). Humor is a brave coping mechanism for people who are otherwise powerless.

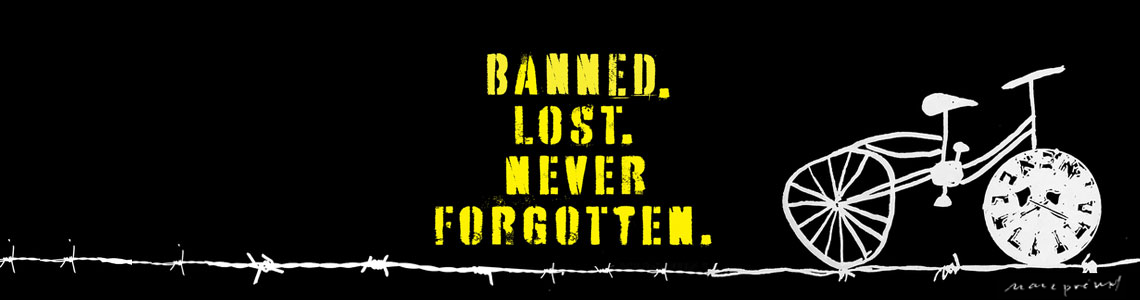

Banned

A cynical joke that made the rounds in European Jewish communities between the First and Second World Wars captured the irrational but growing European antisemitism that accompanied the rise of Hitler and the Holocaust. Here is the joke. The first person says, “The Jews and the cyclists are responsible for all of our misfortunes.” The second person asks, “Why the cyclists?” The third asks, “Why the Jews?”

“Everyone” knew the joke. In her book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt characterized the joke as “the best refutation” of identifying the Jews as “the hidden authors of all evil” (1973, p.5). The playwright Berthold Brecht uses the joke in The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. Some who were born in Europe in those years remember how their mothers, on hearing disturbing news, would say with a mix of frustration and fear, “… And the cyclists,” meaning “We Jews get blamed for everything.”

In 1944, a cabaret called The Last Cyclist, which took its inspiration from the joke, was written and rehearsed in Terezín. It is a bitter allegory, a zany, avant-garde comedy with archetypal, commedia dell’arte characters. The basic plot involves a group of lunatics who escape from the asylum and set out to take over the world. Because they hate their bike-riding physician, they target everyone who rides or owns a bicycle, the people who sell biking gear, and all who have been related to cyclists for generations back, pinning blame on them for every trouble afflicting society. Their rallying cry is “Death to cyclists.” Ma’am is the lunatic leader. Rat is a hospital orderly who becomes her partner in evil.

Together with their lunatic followers they create and exploit growing anti-cyclist hysteria and plot to send everyone who has anything to do with bicycles to Horror Island, where they will be not-so-slowly starved to death. When Ma’am has a moment of hesitation, Rat reminds her that “cyclists always make the best scapegoats”. A sad sack of a hero, who buys a bike to impress his girlfriend, becomes the lunatics’ prime enemy. Complications – and subplots – follow, culminating in the lunatics’ foiled attempt to send him, the last remaining cyclist, into space in a rocket ship. Good thus conquers evil, but only on the stage. “Out there, where you are,” as the hero’s girlfriend reminds their Terezín audience, “the rule of madness continues.”

Nothing in the original production in Terezín is about the Holocaust, or Nazis, or Jews. The camp inmates didn’t need that information; they were living it. They wanted to be distracted and amused. And The Last Cyclist gave them all that and more: a frisson of excitement and daring. The allegory was clear to all of them. It mocked the dangers of totalitarian, herd-like behavior, and the frightening extremes to which bullying can lead. They understood that they, the prisoners in Terezín, were the cyclists – and the lunatics intent on destroying them were the Nazi SS guards, and that Horror Island was where they were now or, perhaps, even worse, was the dreaded, unknown “East” they feared awaited them.

The Red Cross visit is mocked in a scene in Karel Svenk’s play The Last Cyclist. Although this scene was possibly written by Šedová for its 1961 production, the visit took place either before or around the time the cast was rehearsing in 1944. And it was certainly something every camp prisoner knew about because elaborate preparations for the visit were carried on over nearly half a year.

The Council of Elders didn’t find the show funny or exciting. They were terrified of SS reprisals because the explicitness of the satire and its references to the irrational behavior of dictators and their followers were so blatant. They banned the production immediately following the dress rehearsal. Among the hundreds of productions prisoners mounted, only two were banned by the Council: The Last Cyclist and an opera called The Emperor of Atlantis, by Viktor Ullmann, in which Death abdicates. Both were too overtly anti-Nazi, too dangerous.

Karel Švenk, the playwright, was a young actor/composer/director born in Prague in 1917. In his late teens and early 20s, he was one of the pioneers of the edgy, immensely popular avant-garde theater in that city, working as part of a theater group whose name is essentially translated into English as the Theater of Needless Talents. An ardent leftist, he very early on introduced political commentary into his work.

Švenk was deported to Terezín on November 24, 1941, on the very first transport, designation “Ak,” one of 342 young men sent to transform the garrison town into a “holding” camp. He brought with him an ebullient sense of humor and the resolve to help himself and his fellow prisoners stay strong, and he very successfully used laughter and satire to achieve those goals. As a result, he was a hero to the Jews in Terezín. He is lovingly remembered in survivor memoirs as “a sad clown with extremely expressive eyes” and a biting wit, “inexhaustibly inventive, always up to practical jokes and improvisations.” Again and again, he is described as Chaplinesque, as reminiscent of Buster Keaton: “a born comic, an unlucky fellow tripping over his own legs but always coming out on top in the end.” ( Sedova, 1965, p. 224) His wit was often unsubtle, unsettling, and bold. The cabarets he wrote in the camp “reflected all the irony, all the mockery, all the distortion of ghetto life” (Bondy, 1989, p. 291).

Švenk and Rafael Schächter (the conductor who led the musical performances of the Verdi Requiem in Terezín) are credited with beginning the cultural activities in the camp. Early in 1942, they produced their first cabaret, The Lost Food Card. The program’s finale, the “Terezín March,” had a simple, catchy melody. It spoke to the prisoners’ situation in the camp, and to their hopes for a brighter future. It became the unofficial anthem of the Terezín inmates, reprised by demand in all Švenk’s later productions, and sung or hummed or whistled by prisoners on every other possible occasion. The lyrics are cited and sometimes quoted in full in many survivor memoirs. The song looks forward with hope to that “tomorrow” when the prisoners will return home and laugh, as Švenk predicted, “on the ruins of the ghetto.”

Author’s Note: My script of “The Last Cyclist” includes Švenk’s most famous and memorable song, known as the “Terezín March (or “Hymn”or “Anthem”). This song was so energizing and electrifying that it captured the hopes of the Terezín inmates, who lived constantly with a sense of numbing despair. It became their unofficial “anthem.” It was reprised again and again to conclude Švenk’s cabarets, sung spontaneously by the audience at the end of other camp productions, and is cited repeatedly and even reproduced word for word in memoirs and other descriptions of the camp written by survivors. The version I wrote for my production is the chorus, modified to omit a reference to the number of words the prisoners were allowed to write on the heavily censored, optimistic postcards they were compelled to send to friends and neighbors back home; it would have had no meaning for audiences today, and for me to include it would have required too much explanation. Instead, I incorporated into the chorus some of the text from one of the verses.

Here are the lyrics as they appear in my script:

Terezin March

Where there’s a will there’s a way.

We’ll survive another day,

And together, hand in hand,

We’ll laugh at hardship.

Don’t despair, still believe

That the sun will shine again

And we’ll live to turn our backs on Terezín.

Listen!

Soon we will be homeward bound,

Our lives will start again.

And tomorrow we will pack our bags,

Free women and free men.

Where there’s a will there’s a way.

We will live to see that day.

On the ruins of the ghetto

We will laugh!

(Svenk’s music is further described by the Terezin Music Foundation).

Parody, jokes, improvisation – all this attracted hundreds of people to the attic where Švenk’s cabaret was performed. When watching … people forgot, albeit for a short moment, the surrounding reality – death, hunger, deportations to the East…. The house was always full; people resorted to various tricks to get the tickets. (Makarova, 2022)

Viktor Ullmann, composer of The Emperor of Atlantis and a noted music critic who even in the concentration camp did not compromise his strict standards of professional excellence, called Švenk “our Terezín Aristophanes” who can himself “hardly imagine just how much material, talent and inventiveness he has in stock. ‘Shake before using’ – but this time it is the patient himself, not the medicine, that gets shaken. Having laughed for two hours, you feel simply incapable of criticizing the show.” (Ludwig, 2021, p. 171)

Švenk wrote four other cabarets in Terezin: Anything Goes (May 1942, forty-two performances), Ghetto in Itself (August 1942, thirty-eight performances), Long Live Life, or Dance Around a Skeleton (early 1943, twenty performances), and his last cabaret, The Same but Different (March 1944, twenty-nine performances) (Karas 1985, 143: Makarova et al. 1995, 136-37).

Lost

On October 1, 1944, Karel Švenk was among the hundreds of people sent to Auschwitz on transport “Em.” From there he was sent to Meuselwitz, a slave labor sub-camp of Buchenwald which produced ammunition and arms components. Vili and Jiří Suessland, lifelong friends and fellow actors from Prague, were deported with him to Auschwitz and then to Meuselwitz. Immediately after liberation and shortly before his own death, Vili wrote about their experiences in the labor camp, where “those who did not fulfill the norm were flogged with a rubber hose.” He described how Švenk, a man who had been so “immensely popular … overwhelmingly interesting … a legendary person,” had become “quarrelsome, hysterical and rather unpopular.” The three of them were among the prisoners sent, barefoot, starving, and suffering from diarrhea, on a long “death march” in April 1945 when the Nazis evacuated Meuselwitz in the face of the advancing Allied armies. Švenk’s spirit was broken, his energy gone; he could not keep up with the marchers.

Švenk, who inspired so many and gave them hope, at the end had none left for himself. Disoriented and fatally exhausted, he died at the age of twenty-eight just a few weeks before the end of the war in Europe. Vili wrote: “I hid Švenk in the straw of some barn…We don’t know what happened to him” (as cited in Greenbaum, 2008). Both brothers died a few weeks after liberation, among the many short-lived-survivors too ill to survive.

Švenk had been on transport lists twice. The first time, he gave all his writings to a friend to preserve for him and then he was not deported. The second time, he took his manuscripts with him. They are forever lost.

Never Forgotten

Although The Last Cyclist was seen in Terezín only in rehearsals, its message – and its notoriety, because it had been banned – kept it from being forgotten. It is frequently mentioned in survivor memoirs and was the only Terezín cabaret described in detail in an essay called “Theatre and Cabaret in the Ghetto of Terezín” by Jana Šedová in the book called Terezín (p. 224). In that essay, she talks admiringly about Švenk and gives a lengthy plot summary of The Last Cyclist as they rehearsed it in 1944.

To the best of my knowledge, Šedová was the only surviving actor of the original Cyclist cast. Jana Šedová (1920-1995), was born Gertruda (Trude) Skallova in Chrudim, Czechoslovakia, a town about two and a half hours from Prague. Although her family was registered with the Jewish community, they were apparently not very observant. In November 1941 she married Otto Popper, who shortly afterward was arrested and deported to Terezín. On December 14, she too was on a transport to Terezín.

From April to June 1942, Popperova was part of a labor brigade of some 100 women sent to work in a forest. While there, she began creating skits to entertain herself and the other women, although she knew very little about theater. When they returned to Terezín, she joined in the theatrical activities that took place after the grueling workday. She appeared in many camp productions, including The Last Cyclist. Because her job was splitting mica, which was needed for the optical equipment the Germans deemed vital to their war industry, she remained in Terezín throughout the war. After liberation, she moved to Prague, took the stage name Jana Šedová and, as she phrased it, “chose the stage for her life career.”

In Prague in 1961, Šedová adapted The Last Cyclist for a production at the avant-garde Rokoko Theater together with Darek Vostřel, the theater’s director. It was part of the theater’s repertoire for that year. Four years later, she wrote the essay in Terezín where I first encountered the story of The Last Cyclist.

In 1965, in 1968, and again in 1993, she gave survivor testimony about her experiences in the camp. The Holocaust scholar, Elena Makarova, who interviewed her in the 1990s, described her as tiny, energetic, feisty, and never without a cigarette in her hand. Trude Popperova – Jana Šedová – died on September 15, 1995.

Reconstructed and Reimagined:

The Backstory of Naomi Patz’ script for The Last Cyclist

I first encountered The Last Cyclist in 1995, when I was invited to write a simple script for a regional high school youth group “arts weekend” focused on the Jews of Czechoslovakia. I based my script on the description of The Last Cyclist in Šedová’s 1965 essay. The teen production was powerfully moving. Now even more intrigued by Šedová’s description of the impact of The Last Cyclist on the Jews who saw it during rehearsals in Terezín, and not knowing then what I later learned, namely that Švenk’s original script no longer existed, I attempted to track it down.

In 1999, a Czech friend, Dr. Jiřina Šedinová, found a typescript of Šedová’s 1961 version of the play in the library of the Theater Institute in Prague. It had never been published. She also found a Czech translator, Dr. Zdenka Marečková, who – extraordinarily and unexpectedly – volunteered her time to make a rough translation of the play because she was so moved by what she read and excited by the possibility of it reaching an English-speaking audience.

At that point, I didn’t yet know that Šedová had rewritten Švenk’s original, so when I opened the attachment to the email from Prague and read the translation, I was shocked! The second act of Šedová‘s 1961 adaptation was markedly different from her 1965 description of the original plot. Then I figured out why that had to be. During the Communist era, references to Jews and the Holocaust were forbidden, ideologically unacceptable. Seventeen years after The Last Cyclist was rehearsed in Terezín, Jana Šedová had finally found an acceptable way to mount the play, wrapping her recollections of The Last Cyclist into a new script about lunatics and cyclists, with her first act very much like her description of the original and the second act speaking directly to Communist overtures to the newly independent African nations.

This wasn’t the Karel Švenk original! I almost abandoned the project, but I realized how effective the brilliant use of satire to address such a serious topic could be. Today, with fewer and fewer Holocaust survivors to make their experiences “real,” I felt an imperative to use Švenk‘s biting satire for the stage.

It was an intriguing (and sometimes tension-producing) challenge to try to reconstruct the last scenes of Švenk’s original plot. I have edited, reconstructed, and reimagined my version of The Last Cyclist based on the following sources: Šedová‘s 1961 adaptation of the 1944 cabaret; her 1965 description of the original script; the illustrations made by František Zelenka in Terezín for costumes and sets for the original production; and hints about and allusions to the original cabaret in the recollections of survivors.

I needed to convey a sense of the hopes, fears, and coping mechanisms Terezín inmates used to preserve their sanity, to remember that they were civilized human beings despite hunger, disease and indignities they were forced to suffer and the constant uncertainties and fears with which they lived. Because there is nothing in the original that mentions Terezín or the appalling conditions of the inmates’ daily existence – the context in which both the humor and the implicit horror of the play become understandable to us – I created new beginning and ending scenes in which Jana Šedová “remembers” back to the night of the dress rehearsal, and Švenk’s cabaret becomes a play-within-a-play. In my adaptation, the play/film ends abruptly with the announcement of an impending deportation.

Why Does The Last Cyclist Still Matter?

The Last Cyclist opens a window onto a little-known aspect of spiritual resistance to the Nazis during the Holocaust. Despite the harrowing conditions under which they were forced to live and work, Jews in Terezín created a remarkable wealth of cultural offerings, including theatrical performances, concerts, recitals, paintings, drawings, and more than 2000 lectures that gave solace and a boost in morale to this humiliated and disheartened group of highly educated, civilized and cultured urbane people who, despite dire rumors, still often hoped that they would be freed.

For many years after the Holocaust, there was a common misconception that the Jews of Europe who were rounded up, put into transit camps, and then deported to death camps went “like sheep to the slaughter.” Despite the Warsaw Ghetto uprising and isolated acts of resistance such as that of the Bielski brothers (told in the book by Nechama Tec [1993] and the subsequent film, Defiance), some viewed acts of resistance as anomalies. Now, we know better. Memoirs, historical accounts, novels, and films delineate myriad instances of bravery and small and large acts of physical and spiritual resistance to the Nazis.

My play was first mounted in St. Paul, MN in 2009. Since then, it has been performed in high schools and colleges, at community theaters, in synagogues, and at Holocaust museums and Yom HaShoah observances around the United States, in Mexico City (in a Spanish translation), in Poland, and in England. It has been on the syllabus of courses on genocide and the creative arts in at least four universities. In 2017, in light of the drastic increase in bigotry, bullying and overt antisemitic incidents, we filmed The Last Cyclist so it could be seen by much wider audiences. Please visit The Last Cyclist website for more information.

The Last Cyclist is an example of the extraordinary resilience displayed by concentration camp inmates. Incredibly, Švenk’s play is funny and was meant to be funny. The audiences in Terezín that attended the open rehearsals of The Last Cyclist laughed and today’s audiences are meant to laugh too. But ours is uncomfortable laughter because we realize that the play is not a joke but a brave protest against totalitarianism. We also know the fate of the cast and the rest of the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

In 1790, President George Washington visited the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island. The letter he delivered to the congregation that day expresses one of the core beliefs of our country from its very beginning, that the United States “gives to bigotry no sanction.” (Sarna, 2005, p. 39). George Washington’s affirmation is in danger today. The Last Cyclist, in a non-confrontational way, reminds us that it is the personal responsibility of every human being to fight intolerance, prejudice, bullying and racism.

Why were six million Jews murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators?

They died because they were not allowed to live.

– Ruth Bondy (1989), Elder of the Jews, p. 447.

References

Arendt, H. (1973). The origins of totalitarianism. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Bondy, R. (1989). “Elder of the Jews”: Jakob Edelstein of Theresienstadt Grove Press

Broughton, S. (1993). BBC Music Magazine.

DeSilva, Cara. (1996). In memory’s kitchen: A legacy from the women of Terezin. Northvale, NJ. Aronson.

Frýd, N. (1965). Culture in the anteroom to hell. In Terezín. Prague. Council of Jewish Communities in the Czech Lands.

Greenbaum, O.L. (2008) The voice of one in the face of tyranny and oppression: the story and legacy of Karel Švenk (1917-1945), a young artist who perished in the Holocaust. [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Hunter College, The City University of New York.

Karas, Joza (1985) Music in Terezin 1941-1945. Beaufort Book Publishers, NY, with Pendragon Press.

Ludwig, M., (Ed.) (2021). Terezin Music Foundation & Steidl-Verlag. Our will to live: the Terezín music critiques of Viktor Ullmann.

Makarova, E. Theater in Terezín. Accessed 2022. Elena Makova Initiatives Group Production. Czech Theater

Makarova E., Makarov, S. & Kuperman, V. (Eds.) (2004). University over the abyss: The story behind 520 lecturers and 2,430 lectures in KZ Theresienstadt 1942-1944. Jerusalem: Verba Publishers.

Makarova E., et al., (1995) Theresienstadt: Culture and Barbarism (1995). Carlsson Bokforlag, Stockholm, Sweden.

Morreall, J (1997). Humor in the Holocaust: its critical, cohesive and coping functions. [Paper presentation]. Annual Scholars’ Conference on the Holocaust and the Churches, Hearing The Voices: Teaching the Holocaust to future Generations, 1997. Holocaust Teacher Resource Center

Pechová Oliva. (1973). Památník Terezín. Arts in Terezin 1941-1945. (Kvíčalová Hana, Trans.). Memorial Terezín, the Small Fort.

Peschel, L. (2014). Performing captivity, performing escape. Seagull Books: London.

Rovit, R., & Goldfarb, A (1999). Theatrical performances during the Holocaust: Texts, documents, memoirs (PAJ books). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sarna, J. D. (2004). American Judaism: A history. Yale Univ. Press.

Šedová, J. (1965). Theater and cabaret in the ghetto of Terezín. In Terezín. Prague. Council of Jewish Communities in the Czech Lands.

Šedová, J. (1961), The Last Cyclist [unpublished, lost manuscript in Czech], archived in the library of the Theatre Institute of Prague. Revised from original and unpublished play by Karel Svenk, The Last Cyclist.

Tuma, M. (1976). Memories of Theresienstadt. PAJ (Baltimore, MD), 1(2), 12-18

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) (2022), Theresienstadt: Spiritual resistance and historical context. USHMM Holocaust Encyclopedia

Six death camps, Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek, and Auschwitz-Birkenau, were used to carry out the systematic mass murder of Jews as part of the ‘Final Solution.’ Murder through poison gassing was done by Nazi design first in gas vans and later in gas chambers. Source: Yad Vashem. See also: ‘Killing center.’

One that bears the blame for others. One that is the object of irrational hostility. Merriam Webster

“…Any actions taken with the intent of thwarting Nazi German goals in the war, actions that carried with them risk of punishment.” Types of resistance include armed resistance, spiritual resistance, organized resistance movements, and other types of resistance. Rowman and Littlefield / Jewish Partisans / Tec 2013