Settings

Music and Concentration Camps: A Look at Terezín

Karen Uslin

Terezín is a small town located about forty miles northwest of Prague, the capital of what is now the Czech Republic. Today, around 2,900 residents live there, and its history has led it to become a memorial and place where people go to learn, visit, and remember (see: Terezín Memorial).

Terezín’s history begins in 1780, when Emperor Joseph II founded the town and named it after his mother, Empress Maria Theresa. The town included two parts: the town itself, and the military prison called the Small Fortress (which became what we now refer to as the Terezín ghetto and concentration camp). The name of the ghetto or camp can itself be described in two ways: Terezín, its Czech name, or Theresienstadt, its German name. In this article, I will use ‘Terezín’ to refer first to the location and then to the Nazi concentration camp or ghetto therein. When Terezín no longer needed to be used as a fortress, it became a military barracks town. The Small Fortress remained in use as a military prison; one famous prisoner who spent time in the Small Fortress prior to the Holocaust was Gavrilo Princip, the man whose assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand sparked World War I.

Terezín’s function would change from a military barracks town to a ghetto and concentration camp in 1941, when the first transport to the camp departed from the city of Prague. The idea to turn Terezín into a camp came in 1939, after Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, and after several years, a concentration camp was constructed in Terezín. The residents living in the town of Terezín were removed to make room for the camp prisoners. The first transports to Terezín in 1941 were made up of men who volunteered for construction work; in return they were promised that their families would remain safe from being sent to the death camps in Poland. Unfortunately, in most cases, those promises were not kept. Subsequently, Terezín served as a ghetto and transit camp, sending prisoners to infamous camps in ‘the east,’ often sites of mass murder in Poland.

Terezín has several elements that make it unique among the Nazi concentration camp system. One of these elements was how the camp was organized and used for deception and propaganda. One of the goals of the Nazis was to use this camp as a false representation of their prison camp system, as if it was a “spa town” where people were happy, culture continued, and elderly Jews could retire. Terezín would misrepresent concentration camps to the outside world, suggesting that Jews were being treated well by the Nazis. Of course, all of this was a horrible lie.

Deception was further elaborated inside the camp through in the hierarchy by which the camp was organized. When Terezín was turned into a ghetto and camp, the Nazis required that the Jewish leaders in Prague submit a list of both Zionist and non-Zionist Jews that could act as a Jewish Council (Judenräte). This falsely suggested that a Jewish “Council of Elders” could “lead” the camp, with one Elder being named the head leader. As in other ghettos during the Holocaust, such organization promoted a general deception that included the illusion that the Jews were self-governing and even policing themselves, if not autonomous, but most such Councils of Elders had very little power. They simply were in place to carry out Nazi directives each day, tragically being forced to choose who would be on the transport lists for deportations. Elders took orders from an SS-commander. “Self-administration” of Terezín is more fully described by the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure.

Life in Terezín

A prisoner’s journey to Terezín began when men, women, and children received their deportation notices, which often arrived three days before they had to report for deportation. Each deportee, first coming from Czechoslovakia and later from Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, or Denmark, could only take a limited amount of luggage with them (Berkeley, 2002 p. 42). Prior to train tracks being built in Terezín, prisoners were taken to the neighboring town of Bohusovice and then walked the two miles to Terezín. Once in the camp, new prisoners were taken to the Schleuse where they were ‘processed.’ This included being cleaned to make sure they had no lice on them, being physically examined, and filling out paperwork. After being processed, the new prisoners were given a work assignment and a barracks assignment. The barracks in Terezín were horribly overcrowded. Rooms that held three to four people comfortably before the war were used to hold as many as seventy people during the war.

Terezín survivor Edgar Krasa said that “Life of the adults was monotonous, the same every day” (2005 email to Karen L. Uslin). Most days contained a mix of work, eating what little food was provided, and trying to survive the stress and horror of camp life. Because of the cramped living quarters, and other aspects of the horrible living conditions, diseases spread quickly. A daily diet in Terezín consisted of substitute (sometimes called ersatz) coffee, watery soup which sometimes included scraps of vegetables or horsemeat, a third of a loaf of bread twice a week, and sometimes some sort of dumpling. Occasionally a teaspoon of margarine or jam was included. Another significant and tragic aspect of life in Terezín involved the ‘transports to the east,’ or deportations. Terezín became a holding camp from which prisoners were regularly sent to death camps in Poland.

International Red Cross Visit

One of the most infamous events in Terezín’s history was the visit from the International Red Cross (IRC) to the camp on June 23, 1944. This visit was preceded by one of many examples of forced labor during the Holocaust. Nazis ordered a “beautification process,” where the ghetto was to be cleaned up by prisoners and made to look like a charming country town. The idea for the IRC visit had its roots in late 1943, when the King of Denmark put pressure on the IRC to visit Terezín; Danish Jews were prisoners in the camp and King Christian X was greatly concerned for their well-being.

The IRC made plans, with Nazi permission, to visit the camp, and the Nazis took this as an opportunity to show the world how “well” the Jews were being treated under their regime. During this temporary measure, buildings were freshly painted, sidewalks were paved, the main square was now opened to the Jews, and it included a coffeehouse and a music pavilion where Terezín’s jazz musicians, called the Ghetto Swingers, would play. A playground for the children was also added. In addition to all of this, however, another consequence of the beautification process was the deportation of anyone who looked unhealthy, so that the IRC would only see vibrant looking people on their visit.

Survivor Edgar Krasa describes his memories of the Red Cross visit and the beautification process:

The ‘beautification’ of the Ghetto was started soon after the commander accepted the idea of a propaganda program. Right after the first transport arrived, tents and prefab buildings were put up on the town square, and all prisoners, men and women, were put to work on war industry and consumer goods that were produced there. A huge barter economy developed in absence of real money. Inside the Ghetto were no German guards except the Nazis in charge of the camp, a Jewish police force was established. Also an economy police, whose job it was to try to prevent stealing community and personal property. When it was decided to invite the International Red Cross, the tents and barracks on the town square were removed, grass was planted, flower beds established, a music pavilion built on the town square for the ‘promenading’ public.

All old people were sent away, so that only young, good-looking people would be seen. A playground was built with swings and everything that is on a playground. I could not understand that members of the Red Cross, who were asked to do the Nazis a favor, agreed not to interview people they met at random on the street, but only those whom they were introduced to by the Commander accompanying them. These were auditioned under threat of deportation to say what the SS wanted the visitors to hear. So were little children, who, when the visitors came to the playground, were given chocolate and had to address the commander [SS Colonel Karl Rahm], whom they have never seen, as uncle, and by his name: Uncle Rahm, again chocolate?! Many children did not even know chocolate because it was not on their ration tickets at home. Everything was a farce. (Edgar Krasa, personal email, 2005).

The Nazis planned every detail of the IRC visit. Everything was for show; prisoners were even placed along the IRC delegation’s route and given whistle signals to respond to by looking as though they were laughing, playing, or walking to work. The IRC also saw several musical activities; these included a performance of the children’s opera Brundibar by Hans Krasa, a performance of Verdi’s Requiem, and the jazz band, the Ghetto Swingers, performing in the coffeehouse pavilion in the center square. The IRC never spoke to any of the prisoners. Once back in Switzerland, the IRC wrote a report saying that nothing seemed out of place (the original report is kept in the H.G. Adler collection in the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam. The NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies is a national and international center of expertise for interdisciplinary research into the history of world wars, mass violence, and genocides, including their long-term social consequences.

The IRC visit was so ‘successful’ that the Nazis decided to make a film, which they titled The Fuhrer Gives a City to the Jews. The film is sometimes referred to by the title Terezín: A Documentary Film from the Jewish Settlement Area. This film, which prisoner and veteran actor Kurt Gerron was forced to direct, was created after the IRC’s visit to Terezín. Intended to be used for propaganda, the film showed Terezín to be a ‘spa town’ where everyone was happy and healthy. Before the film was made, all unhealthy prisoners were deported to Auschwitz. After the filming, prisoners featured in close-ups were also deported to Auschwitz. Approximately twenty minutes of this film survives from Periscope films, and the clip can be found on YouTube.

Nazi Minister of Propaganda Director Joseph Goebbels intended to use the film to prove to the International Red Cross and the world that Jews were being well-treated in the camps. The film, however, is an elaborately staged hoax presenting a completely false picture of camp life. Upon completion, the director and most of the cast of prisoners were condemned to Auschwitz. Only a few survived to attest to the falsity of the film.

Verdi in Terezín

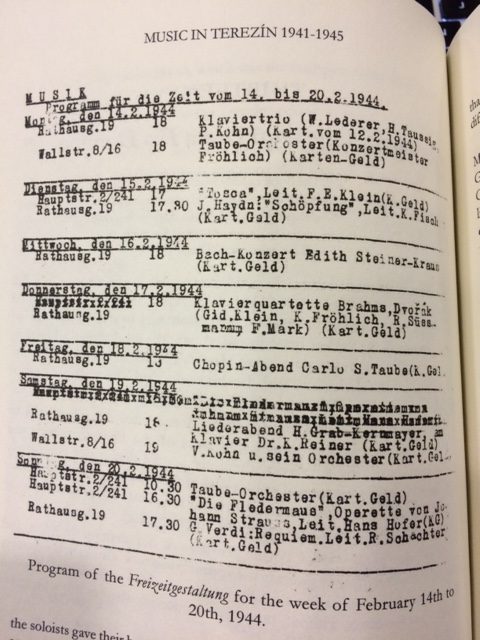

Despite the horrific circumstances in Terezín, culture continued in the camp, thanks to many performing and other visual artists, musicians, writers, teachers, and academics imprisoned in the camp. The first documented musical performance occurred in 1941 and included a chamber music concert (though there had been some prior communal singing at night in the barracks). Cultural activities became an actual part of the governing of the camp, under a department called the Freitzeitgestaltung “Free-time Activities Council.” All kinds of concerts and performances happened in Terezín, including theater shows, sports games, academic lectures.

In 1941, a conductor and pianist named Rafael Schächter was deported to Terezín on one of the first transports to the camp. Born in Romania, Rafi (as his friends called him) came to Prague to go to university and make his music career. He taught private lessons and worked with some of the avant garde theater groups in town before the Nazi laws prevented Jews from working in Prague. Once Rafi and his fellow prisoners were in Terezín, he led nights of singing Czech folk songs in the barracks to help keep everyone’s spirits up as much as possible. When Rafi was sent to Terezín, he brought two music scores with him: Bedrich Smetana’s The Bartered Bride (the Czech national opera), and Requiem by the Italian composer, Giuseppe Verdi. Rafi did not know he would be using these scores in Terezín; he just wanted to have these two musical pieces that meant so much to him close by.

In 1943, with cultural activities at Terezín fairly well established, Schächter decided to attempt a performance of Verdi’s Requiem in Terezín. A Requiem is a Catholic mass for the dead. Since the Middle Ages, Requiem masses, which focus on ideas of salvation and wrath, have been sung in honor of those who have passed away. Members of the musical community, and the Council of Elders, tried to talk Rafi out of doing the Requiem. They did not understand why Rafi would want Jewish prisoners to sing a Catholic work when there were plenty of pieces by Jewish composers that could be sung instead. Edgar Krasa explained Schächter’s motivation:

Schächter[‘s] drive [was] to tell the Nazis that the day of reckoning will come, and they will not escape punishment. He could not tell them in German but thought singing it in Latin he will be able to get it off his chest. Among the objectors were many musicians, rabbis, and the Council of Elders [who] told Schächter that if the Germans find out the intent, they will hang him and deport the whole choir. He persisted. 7 months after the start of teaching the Czech singers Latin and the difficult music by rote, and 3 times losing always sizeable numbers of choir members, the premiere took place. (Edgar Krasa, 2005 email to Karen Uslin).

Despite these objections Schächter persisted. Though he gave the choir members the option of staying or leaving, not one choir member chose to leave.

The choir rehearsed for seven weeks, and the first performance took place in September 1943. Schächter did not think the choir was ready to perform…by all accounts he was a perfectionist! But rumors had begun that transports to the east would be resuming, and the choir wanted the chance to perform before anyone was forced to leave. After that performance, half of the choir was deported to Auschwitz. Schächter rebuilt the choir but again lost half to deportations. He finally got a choir that was able to perform regularly, and by June 1944, the Verdi had been performed fifteen times in Terezín.

Schächter then received a direct order from Nazi officials at the camp to perform the Verdi for the IRC visit. He initially wanted to refuse, but eventually decided the opportunity to direct his musical message to the Nazis themselves was too much of an opportunity to miss. When the IRC came to Terezín on June 23, 1944, about sixty choir members remained to sing the Verdi. This would be the last performance of this piece in Terezín; four months later, in October 1944, most of the choir, Schächter, and most of the primary musicians and composers from the camp were sent to Auschwitz. Many died in the gas chambers, though some of the choir did survive. Schächter himself was transported to two more camps after Auschwitz before dying on a death march in March 1945.

Liberation

Liberation came to Terezín in the spring of 1945. In those last few months, prisoners from other camps were sent to Terezín. The Danish Jews who had been imprisoned there were sent to Sweden under an agreement with the Swedish Red Cross. A few days after Nazi command officially turned the camp over to the IRC on May 2, 1945, Soviet troops came and officially liberated the camp. Due to a typhoid epidemic, prisoners had to stay in the camp for several more months. The last of Terezín’s former inmates officially left the camp in August 1945.

Defiant Requiem

In the mid-1990s, conductor Murry Sidlin was working at the University of Minnesota when he came across a sidewalk sale at a used bookstore. There he found Joža Karas’s Music in Terezín, 1941-1945 and its chapter on the Verdi Requiem. The story stuck with Maestro Sidlin, and when he moved from Minnesota to become Resident Conductor of the Oregon Symphony, he brought the story with him. After several years’ worth research and contacting survivors, on April 20, 2002, Maestro Sidlin and the Oregon Symphony Orchestra premiered the first Defiant Requiemconcert drama in Portland, Oregon.

Defiant Requiem is a multimedia concert drama that honors the story and legacy of Rafi Schächter and the choir that sang the Verdi in Terezín. The entire Verdi Requiem is performed with a full choir and orchestra, amounting to almost 300 people needed for the choir and orchestra. In between the movements of the Requiem, video plays, showing clips of interviews with Terezín survivors (including prisoners who sang in the Verdi choir in Terezín) and clips of the Nazi propaganda film, The Fuhrer Gives a City to the Jews. Defiant Requiem combines all these elements together with narration in order to present the story of Rafi Schächter and the Verdi chorus in Terezín.

Defiant Requiem is a Holocaust commemoration and memorial. The goal is not to re-create for historical accuracy what happened in Terezín but to tell the story in an impactful way and to honor those musical artists who were victims of the Nazis. This can be seen in the trailer to the 2012 documentary, also titled Defiant Requiem, which goes further in-depth in telling the story of the Terezín Verdi performances.

Conclusion

The US Holocaust Memorial Museum affirms that there were more than 44,000 sites in Europe that were used in the Nazi concentration camp system. Music allowed people in this system suffering under tyranny to keep hope and faith alive. One of Terezín’s prominent composers, Viktor Ullmann, wrote twenty-six music critiques and three essays detailing the performances in Terezín. In a 1944 essay, titled Goethe und Ghetto (trans. Uslin), he said:

To emphasize that I have been in my musical work sponsored by Theresienstadt and not inhibited, that we did not merely sit lamenting by the waters of Babylon and that our culture was equal to our will to live. I am convinced that those who have sought to wrest a reluctant substance from form in life and art will prove me right. (Ullmann, 1944. Trans. Uslin, 2015).

Despite being surrounded by the worst of humanity, these musicians and artists found a way to showcase the best of humanity.

The Verdi choir members used their musical talents to show not only humanity but also defiance and resistance through culture. For those who survived, this became something that stayed with them their entire lives. Marianka Zadikow May, one of the few Terezín survivors who sang in all sixteen performances of the Verdi Requiem in Terezín, wrote in the introduction to her published Terezín album that she was:

a Requiem survivor. I survived with, because of, and after the Requiem. I couldn’t say that the music was always protecting me, but I know the music saved my sanity. Whatever is safe, whatever is still human, is not based on any religious belief, but on living music (May, 2008, p.2).

Terezín was a place where music took on a much larger meaning for many of the prisoners and this spiritual resistance shows how culture can be used in ways to make a statement even in the worst of circumstances. In addition to the Terezín memorial, a memorial to the Holocaust has been established at the Jewish Museum in Prague.

References

Berkley, George E. Hitler’s Gift: The Story of Theresienstadt. Wellesley: Braden, 2002.

Defiant Requiem Foundation Retrieved July 23, 2022.

Defiant Requiem film trailer: (July 30, 2012) Retrieved July 23, 2022.

European Holocaust Research Infrastructure: Terezín/self-administration. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

Karas, Joža. Music in Terezín 1941-1945. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Pendragon, 2009.

Krasa, Edgar. Personal e-mails to Karen L. Uslin. August 1, 2005-August 13, 2014.

May, Marianka Zadikow. The Terezín Album of Marianka Zadikow. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Periscope Film: Retrieved July 23, 2022.

Schultz, Ingo. Viktor Ullmann: 26 Kritiken über Musikalische Veranstaltungen in Theresienstadt Reprint (original published Hamburg: Bockel, 1993). Neumünster: Bockel, 2011.

Terezin Memorial Site: Retrieved July 23, 2022.

Uslin, Karen. Grasping at Hours of Freedom: Music in the Terezín Concentration Camp. Dissertation, 2015, The Catholic University of America.

Ghetto: Ghettos were often enclosed districts that isolated Jews from the non-Jewish population and from other Jewish communities. Living conditions were miserable. During the Holocaust, the creation of ghettos was a key step in the Nazi process of brutally separating, persecuting, and ultimately destroying Europe's Jews. Ghettoization: the process of creating these ghettos. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

A Bosnian Serb student who at 19 years old assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, which contributed to the start of World War I. ORIGINS

Judenräte, or Jewish councils, were administrative agencies imposed by Nazi Germany on Jewish communities across occupied Europe, principally within the Nazi ghettos. These councils provided basic community services for ghettoized Jewish populations while also implementing Nazi policies, including providing lists of names for deportation. Wikipedia

A check point in Terezín where incoming prisoners were examined and checked in and given a barracks and work assignment. Jewish Virtual Library

Music written for and performed by a small instrumental ensemble. Chamber Music Columbus

Leisure Time (or Free Time) Activities Council in the Terezín concentration camp which ran the day to day operations of the cultural activities in the camp. GHETTO THERESIENSTADT

A Roman Catholic mass for the dead. Boulder Chamber Orchestra