Settings

Remembering Vel d’Hiv: The Largest Mass Arrest in Wartime in French History

Eileen M. Angelini

On July 16-17, 1942, in Nazi-Occupied Paris, more than 13,000 French Jews, including 4,115 children, were arrested by the French National Police. The victims were held in deplorable conditions for almost five days at the Vélodrome d’Hiver or Vel d’Hiv (French) “Winter Velodrome,” an indoor cycling stadium in Paris’ 15th district. These Jews were then sent to detainment camps outside of Paris. They either died in these camps or were later deported to concentration camps outside of France. This violent mass arrest, where families were forcibly separated, became known as the Vel d’Hiv Round-up and remains to this day the largest mass arrest in wartime in French history. Moreover, this single event accounted for a third of all of the Jews that were sent to concentration camps from France in 1942. Eighty years later, the Vel d’Hiv Round-up remains a painful discussion as evidenced by what Parisian Jewish reporter, Jacques Bielinky, wrote: “A cruel destruction of Jewish families. (Yad Vashem, 2022)”

What made the Vel d’Hiv Round-up so appalling was that it was planned and executed by the Vichy government, policemen and other civil servants. German orders originally included only adult Jews. It was the Vichy government that decided to arrest the children in addition to the adults. Detailed planning of this round-up by the Vichy Government include the leading roles of Prime Minister Pierre Laval and Secretary General of the French National Police René Bousquet. Hundreds of French policemen willingly took part in the Vel d’Hiv Round-up. Prime Minister Laval was the main decision maker in the choice to include Jewish children in the arrests. Laval, an avid antisemite, had been quoted as calling Jews “trash” and devoted much of his time to their “extermination.” Secretary General of the French National Police Bousquet agreed with Laval and was equally instrumental in the decision to arrest children as well as adults. After the Vel d’Hiv Round-up, Bousquet silenced the protests of the French Catholic Church by threatening to remove all tax privileges they received. After Germany surrendered to the Allied Forces, Laval escaped to Spain, returning to France in July 1945. He was put on trial for treason and executed, after trying to commit suicide by poison, on October 14, 1945 (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022). Bousquet was assassinated in 1993. Christian Didier, Bousquet’s assassin, pled not guilty, claiming the act was justified by Bousquet’s war crimes.

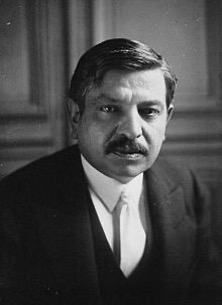

René Bousquet, Secretary General of the French National Police, was a key player in this round-up and deportation. Note the luxurious fur collar on Bousquet ’s coat (shameful behavior given the strict rationing of food and clothing taking place in France during its Occupation by the Germans), the broad smile on his face, and the German officer standing behind him.

One could ask why the French Jews did not resist being rounded-up. Originally the Vel d’Hiv Round-up was planned to take place on or around July 14, 1942, and the goal was to round-up at least 25,000 French Jews as Laval wanted to surpass the total number of victims of any of the round-ups conducted by the Germans in one day across all of Europe. However, July 14th is la Fête nationale française (French) “French National Day” and more commonly known as Bastille Day, which spurred Laval and Bousquet’s efforts to delay the round-up. Underground resistance had word of a possible round-up for July 14th, causing French Jews to flee from Paris. But when the round-up did not take place on the 13th or on the 14th or on the 15th, some French Jews started to return to their homes in Paris. While the actual number of French Jews rounded-up on July 16th and 17th is horrifying, especially because children were included in the round-up, Laval failed to attain his goal of 25,000, even after going beyond the Paris region and clearing out Jewish hospitals of the sick and the elderly.

When I interviewed Régine Winder Barshak, a Vel d’Hiv survivor in 2000, I was struck by her comment that, when the French National Police knocked on her family’s apartment door in the middle of the night, asking them to collect their belongings and go to the police station to verify their identities: Nous étions un peu bête. (French) “We were a bit stupid. (La France divisée, 2001).” But the point is that Régine’s family trusted the French National Police as they did not think that France would deport its own citizens. Régine was able to escape from Drancy, the internment camp near Paris where Jews stayed before deportation to Auschwitz, because her mother convinced the German Commandant to release Régine and her brother as they were French-born Jews. In this particular case, the German Commandant was not aware that Laval had ordered the deportation of Jews from France whether they were foreign or native born, in addition to the order to deport French Jewish children. A few days after retrieving the key to her family’s apartment, Régine heard scratching at the apartment door. When she opened the door, two French National Policemen were sealing the apartment as it was supposed to have been vacated. When asked what she was doing there, she replied that she lived there. One policemen said Mademoiselle, si vous êtes insolente, on vous renvoie, d’où vous venez. (French)“Miss, if you are insolent, we will send you back, where you belong.” This implied being sent back to Drancy, causing Régine to speculate that he was trying to warn her (La France divisée, 2001). This may very well have been the case as I have been told by survivors that not all members of the French National Police were willing participants in the Vel d’Hiv Round-up, clarifying that if the officers did not participate, then their families would be deported.

This first photo of the Vel d’Hiv Round-up shows French Jews casually waiting, with even one man sitting on the ground and leaning against the wall of the building. Directly in front of this man, is a couple speaking with a French police officer.

This second photo from the Vel d’Hiv Round-up shows that the French Jews are not overly panicked, quietly and obediently following the French police officer with even one man smiling directly at the camera. There are no German officers present. Also, even though it is the middle of July, the men are wearing heavy winter clothing, probably thinking that they were headed to a work camp and not an extermination camp.

In this third photo from the Vel d’Hiv Round-up, we see children who have been separated from their parents. One can easily imagine that the trio of children who are at the head of the line is of three brothers, the oldest brother (center) must shoulder the responsibility of taking care of his younger brothers, with one not fighting against having to hold the hand of the oldest brother.

In contrast to the “calmness” that seems apparent in the first two photos of the round-up, survivor testimony speaks to how, as the French Jews were being transported to Vel d’Hiv, many Parisians cheered. Some testimonies speak to the violent manner in which the French National Police separated fathers from their families and then mothers from their children. Furthermore, conditions inside Vel d’Hiv were deplorable. These French Jews were given no food and were provided with only one source of water, a single fire hydrant. There were no working bathrooms. The summer heat combined with the lack of ventilation soon resulted in a horrible stench.

To understand how the French government and people have since dealt with the pain and shame of this traumatic event, it is necessary to frame in a meaningful and concrete manner how France has dealt with les années noires (French), “the dark years,” and successive periods that followed the end of World War II. Henry Rousso (1994) suggests four phases of memory of Vichy France:

- Unfinished Mourning (1944-1954)

- Repressions (1954-1971)

- The Broken Mirror (1971-1974)

- Obsession (1974-present)

Since the premiere of Marcel Ophuls’ groundbreaking documentary on the Occupation years in France, Le Chagrin et la pitié (French) “The Sorrow and the Pity” (1969), France has undergone a radical transformation. French people – writers and historians as well as ordinary citizens – have transformed the ways they understand and represent to themselves the Vichy period in their country’s history. The Vel d’Hiv Round-up has long been a source of deep guilt among the French people. It was not often discussed in politics or in school textbooks for almost five decades after the end of the war. In fact, many French citizens denied its occurrence. Finally, in 1995, President Jacques Chirac issued an official apology at the Place des Martyrs juifs du Vélodrome d’Hiver (French) “Memorial to the Jewish Martyrs of the Winter Velodrome” that officially recognized this horrific event:

“Déportation des Juifs de France : La France reconnaît sa responsabilité”

… la folie criminelle de l’occupant a été secondée par des Français, par l’état français. La France, patrie des Lumières et des Droits de l’homme, terre d’accueil et d’asile, la France ce jour-là, accomplissait l’irréparable. Manquant à sa parole, elle livrait ses protégés à leurs bourreaux… Soixante-quatorze trains partiront vers Auschwitz.

Soixante-seize mille n’en reviendront pas. Nous conservons à leur égard une dette imprescriptible.

… Je veux me souvenir que cet été 1942, qui révèle le vrai visage de « la collaboration, » dont le caractère raciste après les lois anti-juives de 1940, ne fait pas de doute, sera pour beaucoup de nos compatriotes, celui du sursaut, de point de départ d’un vaste mouvement de résistance car il y a aussi la France droite, généreuse, fidèle à ses traditions, à son génie. Comment négliger les valeurs humanistes, les valeurs de liberté, de justice, de tolérance qui fondent l’identité française et nous obligent pour l’avenir.”

“Deportation of Jews from France: France Recognizes its Responsibility”

… the criminal madness of the Occupant was supported by the French, by the French state. France, home of the Enlightenment and the Rights of Man, land of welcome and asylum, France that day committed the irreparable. Breaking its word, it delivered those it protected to their executioners… Seventy-four trains will leave for Auschwitz.

Seventy-six thousand will not return.We maintain an imprescriptible debt towards them.

… I want to remember that this summer of 1942, which reveals the true face of “collaboration,” whose racist character after the anti-Jewish laws of 1940, is no doubt, will be for many of our compatriots, that of a start, the starting point of a vast resistance movement because there is also a righteous France, generous, faithful to its traditions, to its genius.How can we neglect the humanist values, the values of freedom, justice, tolerance which are the basis of French identity and guide us for the future. (Translation by E. Angelini)

The Vel d’hiv round-up has since become a symbol of French collaboration in the deportation and eventual extermination of Jews living in France. France now annually commemorates the deportation of the Jews on July 16 at an official ceremony in the Place des Martyrs Juifs du Vélodrome d’Hiver. In 2022, Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne attended the ceremony in the presence of Paris Mayor Anne Hildago, emphatically affirming “N’oubliez pas, n’oubliez jamais!/ Don’t forget, never forget! (Le Figaro 2022b)” The monument at the Place des Martyrs Juifs du Vélodrome d’Hiver in honor of the victims of the Vel d’Hiv Round-up was erected in 1994. It is located in Paris, Metro Bir Hakeim, very near the Eiffel Tower. As one can see in the photo of the monument below, it has a row of bushes that prevent one from seeing it from the street, thus making the monument difficult to find unless one knows exactly where to go. Why is the monument hard to find? Is it to hide French government guilt? Or is it to protect the monument from anti-Semitic violence? There is no official explanation.

Today, the actual Vélodrome d’Hiver no longer exists. In its place is a memorial plaque describing what once stood there. The plaque was erected on the Boulevard de Grenelle in the 15th district of Paris, facing metro Bir-Hakeim, on July 20, 2008. The ceremony was led by Jean-Marie Bockel, Secretary of Defense and Veterans Affairs, with Simone Veil, a Holocaust survivor and former minster, and anti-Nazi activist Beate Klarsfeld in attendance (Wikipedia 2022).

The 16th and 17th of July 1942

13152 Jews were arrested in Paris and its suburbs

Deported and assassinated at Auschwitz

In the Vélodrome d’Hiver which stood here

4115 children

2916 women

1129 men

were detained in inhumane conditions

by the police of the Vichy Government

on order of the Nazis occupants

to those who tried to help them

that they be thanked

those who pass by here, remember!

(Translation by E. Angelini)

Of note on this memorial plaque is the fact that 4115 plus 2916 plus 1129 equals 8160, not 13,152. The likely reason is that not all of the French Jews arrested and deported during the Vel d’Hiv Round-up were detained in the velodrome. In addition, the five Hebrew letters in the lower right-hand column are a tribute to what one will find on Jewish tombstones. At the bottom of most Jewish tombstones you will often find an abbreviation ת נ צ ב ה of a verse from the Bible, the first book of Samuel, 25:29, “May his soul be bound up in the bond of eternal life.” The other Hebrew text on a headstone or memorial marker will be the deceased’s Hebrew name.

Fortunately, thanks to Chirac’s official recognition of the Vel d’Hiv Round-up, there is more understanding and interest of this singular event of the Holocaust. Perhaps the most well-known manifestation of this interest is the novel, and subsequent film, Sarah’s Key (2007 novel by Tatiana de Rosnay; 2010 film directed by Gilles Paquet-Brenner). Sarah’s Key follows a journalist in Paris as she uncovers the truth about her new apartment which centers on the truth about a particular family in the middle of the Vel d’Hiv Round-up. Critics argue that the two stories that are at work in this film, that of the journalist in modern day and that of Sarah and her family during the Vel d’Hiv Round-up, are sometimes downplayed in the film. Some feel that the history that is meant to be honored is trivialized at some points. However, critics agree that the film keeps the audience guessing as to what exactly happened. When the audience finally finds out, the result is heart-wrenching.

Another significant feature-length film about the Vel d’Hiv Round-up is the 2010 French film La Rafle (French) “The Round-Up,” directed by Rose Bosch. The film follows a young boy, Jo, as he is arrested and held at Vel d’Hiv. At Vel d’Hiv, he is introduced to a Protestant nurse and a Jewish doctor. The audience sees Jo transported to a detainment camp, from which he escapes just before the children are to be sent to an extermination camp. Years later, the nurse searches for survivors and finds Jo. Hailed by critics as a powerful film with examples of everyday bravery and those who would collaborate with the evil of the world. This film shows how the French people cooperated with the Germans in their goal of extinguishing the Jews. The real horror of this film, according to critics, is how the film focuses on the children and how life in Occupied France as a French Jew is viewed through the eyes of children. The audience sees them interacting with friends and family in freedom and watches as that freedom is stolen away from them.

The magnitude of the monument at the Place des Martyrs Juifs du Vélodrome d’Hiver and the Vel d’Hiv Round-up memorial plaque cannot be overstated. Given recent political events in France, specifically right-wing Jewish author Eric Zemmour’s shocking climb in the polls during the 2022 French presidential elections, are a blatant reminder that we must not let the stories of past atrocities be forgotten. In their article, “Author Eric Zemmour, the French Jewish Trump, Storms to Top of Presidential Polls,” Mitchell Abidor and Miguel Lago (2021) explain:

In his 2014 bestseller Le Suicide français, Zemmour made the claim that the Vichy government (1940-1944) actually protected French Jews. That this was simply false was amply demonstrated by historians; that it did nothing to change his mind was made abundantly clear when he repeated the claim as recently as September 2020. Nor did it end with Vichy. Zemmour has also lamented the focus on the Holocaust in French schools, claiming that it was not a “central” event of the war. That such a comment would be forbidden to a non-Jew is proved by the fate of Jean-Marie Le Pen who, in 1987, dismissed the Holocaust as a “point de detail” of the war. Le Pen (and, by extension, his party) was condemned as an antisemite, a label he has never been able to shake, and which played no small part in his replacement as party leader by his daughter Marine, culminating in the later rebranding of the Front National as the Rassemblement National.

Even more distressing is Zemmour’s position on there not being a need for memorials dedicated to Jews who perished during World War II nor for the French to apologize for the crimes against humanity that it conducted during the Occupation. Abidor and Lago (2021) elucidate:

But Zemmour goes further than Le Pen père. He is opposed to any memorialization of the murder of the Jews during the Second World War, and of laws protecting the memory of the Holocaust. He rejects the legitimacy of the apologies offered for France’s role in the massacre of its Jews, claiming this was part of an enterprise to make the French feel guilty for crimes perpetrated by Germans alone. In his latest book, which sold 200,000 before it was even published, Zemmour cited the work of “anthropologists” when he labeled the four Jews killed by a terrorist at a Jewish school in Toulouse in 2012 as “above all foreigners,” because their bones were eventually buried not in French soil but in Israel. (According to Zemmour’s anthropologists, it is the final resting place of one’s remains that determines nationality.) Not even Captain Dreyfus escapes Zemmour’s scorn, as he insists that the French general staff had good reason to suspect him of espionage since he was “German.” Alfred Dreyfus was, in reality, Alsatian, and his family chose France after Germany conquered Alsace in the Franco-Prussian War. It is not surprising that the monarchist and antisemitic organization L’Action Française, which led the charge against Dreyfus in the 1890s, posts videos of Zemmour on its YouTube channel.

Most likely in response to Zemmour’s rise in the polls, President Emmanuel Macron began to make noteworthy homages to World War II victims. For example, on Tuesday, January 25, 2022 (two days before International Holocaust Remembrance Day), Macron attended a memorial in Oradour-sur-Glane to honor the memory of the 643 residents massacred by a Nazi SS unit on June 10, 1944. He presented Robert Hébras, the lone survivor, with the National Order of Merit and hinted at the dangers of supporting the far-right: “Racism and anti-Semitism are now being legitimized by a certain political discourse. (RFI, 2022)”

Sunday, July 17, 2022 marked eighty years since the Vel d’Hiv Round-up and with it comes the dedication of la gare de Pithiviers/Pithiviers train station as un lieu de mémoire et de témoignages/a place of memory and testimonies. Eight convoys were sent from Pithiviers to Auschwitz-Birkenau, making it the second deportation site after Drancy. The site’s dedication provides Macron with another opportunity to deliver an “offensive speech against anti-Semitism on Sunday (Le Figaro, 2022c).” More importantly, Jacques Fredi, Director of the Mémorial de la Shoah, stated “Cette gare, c’est le lieu où l’évènement français devient génocide européen. (…) C’est un lieu de mémoire unique en France,” (French) “This station is the place where the French event becomes European genocide. (…) It is a unique place of memory in France,” continuing that the site is intended primarily for schoolchildren (Le Figaro, 2021a). May memorials such as the monument at the Place des Martyrs Juifs du Vélodrome d’Hiver and the Vel d’Hiv Round-up memorial plaque continue to be preserved and maintained so that the victims are honored and never forgotten. Moreover, may ceremonies like the one with Chirac in 1995 and Macron in 2022 as well as films such as Sarah’s Key and La Rafle continue to raise the public’s awareness of the need to preserve and maintain these memorials.

References

Abidor, Mitchell and Miguel Lago. (2021, October 21). Author Eric Zemmour, the French Jewish Trump, Storms to Top of Presidential Polls. Tablet.

Angelini, Eileen. “France: World War II Occupation and the Holocaust.” The Holocaust: Remembrance, Respect, and Resilience, edited by Michael Polgar and Suki John, Pennsylvania State University, 2022.

Bosch, Rose. (2010). La Rafle. Film.

De Rosnay, T. (2008). Sarah’s key. St. Martin’s Press.

Encyclopedia Britannica (2022, July 11). Pierre Laval.

La France divisée (France Divided). Dir. Eileen M. Angelini and Barbara P. Barnett. Carbondale, IL and Rosemont, PA: AATF French and the Agnes Irwin School Holocaust Project, 2001.

Le Figaro. (2022a, 17 July). 80 ans après la rafle du Vel d’Hiv.

Le Figaro. (2022b 17 July). Rafle du Vel d’Hiv: Élisabeth Borne appelle à «ne jamais oublier».

Le Figaro. (2022c, 17 July). Vel d’Hiv: Macron prononcera un «discours offensif» contre l’antisémitisme dimanche. Web.

Ophüls, Marcel. (1969). The Sorrow and the Pity [Documentary].

Paquet-Brenner, Gilles. (2010). Sarah’s Key. Film.

RFI (2022, 12 July). France Pays Homage.

Rousso, H., Goldhammer, A., & Rousso, H. (1994). The Vichy syndrome: History and memory in France since 1944. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer and foreword by Stanley Hoffman. Harvard University Press.

Talmor, Angélique. (2022, April 7). Eric Zemmour Has a Vision for French Jews. Will They Follow It? Mosaic Magazine. Web.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “France.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 18 June 2012.

Wikipedia (2022, July 11). Vel d’Hiv Roundup.

Yad Vashem (2022, July 11). Deportation from France.