Representations

The Holocaust and 21st Century Media

Melissa Stanley and Scott Metzger

Introduction

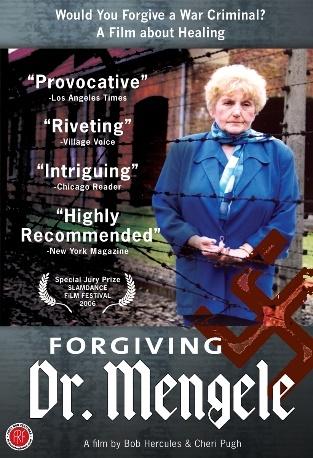

This chapter looks at three categories of visual media that maintain strong influence in the 21st century: popular film, documentary or educational film, and web media. We explore and examine how these media represent the Holocaust. Scholars have shown increasing attention to Holocaust representation in the interconnected areas of film and literature (Baron, 2010; Eaglestone & Langford, 2008; Brownstein, 2020) and in Holocaust education (Schweber, 2010). Popular films are often commercial, mass-media features, such as the Pianist (2002) and The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (2008). Documentary and educational film also has a long history and 21st century examples include work by PBS, BBC, and many others, along with feature-length documentaries such as One Day in Auschwitz (2015) and Forgiving Dr. Mengele (2005).

Web media refers to shorter-length videos available online, often on YouTube. Examples of this type of media are in educational websites dedicated to Holocaust education, such as Echoes and Reflections, Yad Vashem, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), and iWitness, along with YouTube channels. Some YouTube channels such as Crash Course or Time Ghost History serialize a wide range of historical events while others focus specifically on the Holocaust, such as the USHMM ‘First Person’ interview channel. Many online web media are free to use, with or without a user account. Each type of media can be valuable for learning about and understanding the Holocaust and its aftermath. However, each media source is different, and some have limitations, so the viewer is wise to evaluate both source and content. Some of the media detailed in this chapter are included because they are useful for learning about the Holocaust, while others are problematic for learning about the Holocaust.

Evaluating Historical Media

When evaluating any type of historical media, we cannot assume the film, documentary, or video is completely historically accurate. Sometimes this is intentional. For instance, the film The Book Thief (2013) may seem like it is based on a true story, but it is not. The film does depict some factually based events, such as the burning of books by the Nazis and Kristallnacht, but the characters and storyline are fictional. One of the first steps in evaluating historical media is fact-checking. Does what is being portrayed line up with historical facts? If not, why? Media that cannot be supported by historical fact may be displaying bias.

Bias can be identified by asking three simple questions. What facts are inconsistent with historical accounts? Why might those making the media ignore or select particular historical facts? What is the narrative, or overall historical meaning or messaging conveyed by this media? Media creators can selectively use some historical facts and ignore others, which may advance political or social perspectives, including antisemitism, that favor a particular national, ethnic, or group identity or ideology over others. Distortion of history, including Holocaust distortion, can result from this kind of bias because inaccurate or selective narratives can become more widely known to the general public and compete with historical facts. Examples of this are Holocaust distortion and Holocaust denial, which have been condemned by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA).

These three questions will help you determine the motivation behind creation of the media you are viewing, including the form it takes (commercial movie, documentary, web video, etc.). They are good questions to ask yourself when you engage with any type of media. It is important to always remember that all media are created by people for particular purposes. This is not to say that decisions about what historical information to communicate always come from bad intentions, rather it highlights the need to consume media critically. Even when intentions are good, purposes and decisions can still reflect unintended or unavoidable bias in messaging or content. (Marcus, Metzger, Paxton, & Stoddard, 2018).

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) and Echoes & Reflections share important guidelines for evaluating Holocaust education and media. They are helpful to reference when engaging or choosing media to engage with. When viewing Holocaust media, use the following guidance from USHMM and Echoes & Reflections to help ask the right questions.

The Holocaust was not inevitable. The Holocaust was a result of systematic policies, actions, and inactions by governments and groups of people. Media that portrays the Holocaust as an inevitable event that could not have been stopped should be avoided.

The Holocaust was complex. Consider multiple, balanced perspectives. Some media may oversimplify the Holocaust by only representing one perspective or experience. One example of a common misconception is that all concentration camps were extermination camps. Films, and even documentaries tend to focus on the more well-known aspects of the Holocaust such as the concentration and death camp system in Auschwitz. Films may also only depict Jewish people as the victims of the Holocaust, when in reality, other groups were targeted as well.

Avoid romanticizing history. The Holocaust is sometimes difficult for people to learn about because it was so horrific and so many lives were taken. In an attempt to lessen that difficulty for viewers, those producing media may tend to keep only some facts and fabricate the rest. Movies like The Boy in Striped Pajamas (2008) seek to make a difficult historical reality less difficult for viewers by embracing wishful thinking. Media that romanticizes the Holocaust and other difficult events in history is problematic because the viewer may accept it as factual. Movies that romanticize the Holocaust also intentionally or unintentionally encourage misplacement of the viewer’s empathy from the victim to other figures. In the example of The Boy in Striped Pajamas (2008) empathy is redirected from the Jewish victim to the son of the German camp officer.

Make the Holocaust relevant and foster empathy. Often we see the Holocaust represented simply in terms of statistics or infographics. It is important that we do not forget that those statistics represent enormous harm to real people. If we only look at statistics, we can lose sight of the fact that the Holocaust harmed entire communities and families, as well as individuals. Holocaust media can reflect this by striking a balance between representing the totality of the Holocaust and depicting human experience in ways that foster empathy and connect or relate to diverse audiences. The Pianist (2002) is an excellent example of a film that is both relevant and fosters empathy. It begins by depicting the broad effects of the Holocaust for Jewish people in Warsaw and then switched to focus on Władysław Szpilman’s individual experience.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Guidelines for Teaching about the Holocaust include more specific information for teachers and other educators. Extensive resources are also easily accessed online through the Echoes & Reflections Pedagogical Principles for Effective Holocaust Education.

Popular Film

Popular film or movies are full-length features produced for commercial distribution to mass audiences, often globally and increasingly through streaming services. While historical movies are occasionally produced for artistic purposes, most movies are made for profit. This profit motive often influences what kinds of movies are made. As a result, there are fewer movies about the Holocaust than, for instance, WWII action movies. Holocaust films are those that significantly depict Jews who suffered at the hands of Germans or their proxies during World War II or those who helped (righteous, upstanders, rescuers) or hurt (perpetrators) Jews during the Holocaust. Holocaust films can include depictions of events during and/or after the Holocaust. After the Holocaust, protagonists are more formally defined as victims, survivors, and perpetrators (Brownstein 2021, 13-16).

It is important to note that Holocaust films are not always created from the perspective of Jewish or other groups harmed by persecution and mass atrocities. One of the most highly praised Holocaust films, Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), focused heavily on the conflict between its two non-Jewish figures, Oskar Schindler and concentration camp commandant Amon Goeth. As Brownstein (2021) shows in his extensive review, certain perpetrator characters are well-represented in film. Frequently represented perpetrators include Dr. Josef Mengele and Nazi SS officer Adolph Eichmann, whose capture by Israeli agents is the subject of the 2018 film Operation Finale. Eichmann’s war-crimes trial in Israel in 1961, was the first-ever televised. “Convicted of crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and membership in a criminal organization,” Eichmann was executed by hanging in 1962, the only time that Israel has enacted a death sentence (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, USHMM Encyclopedia, 2022).

When it comes to learning about the past, movies have both great potential and pitfalls. No other type of media can offer as much visual impact or emotional power as feature film (Marcus et al., 2018). They make the past come alive through visualization and drama. However, this kind of visual storytelling also requires considerable imagination on the part of the filmmakers. The film needs scene details and dialogue, along with a clear narrative of heroes and villains and moral lessons that satisfy popular audiences. Still, history rarely conforms to popular tastes and expectations. Consequently, historical movies often balance authenticity with public appeal.

Holocaust films can be factually accurate, based on historical research and documentation. The Pianist (2002) is one example. Popular film can be valuable because it captures the attention of the audience more easily than documentaries, which may be perceived by some people as dry or boring. Bridging the gap between authenticity and imagination, popular film makes it easier for the viewer to be emotionally invested in what is being watched. Despite this, Holocaust movies are not always a reliable source for factual details. The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (2008) is one example that may seem plausible or feel authentic, but in reality is completely fabricated. This becomes problematic when teachers or students view or use this film, and others like it, to teach or learn about the Holocaust. It is a false narrative that can distort people’s understanding and learning of the Holocaust (Marcus, 2017).

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum provides bibliography and videography resources for teaching the Holocaust, including a rubric to evaluate books and visual media under consideration. Everything is freely available to teachers, thanks to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

All films, including those in this chapter, should be previewed by educators before sharing with students or others.

The Pianist

The Pianist, released in 2002, is based on the life of Holocaust survivor, Władysław Szpilman. Szpilman was a classical pianist in Poland who played for the Polish National Radio before Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939. While displaced and moved into the Warsaw Ghetto with his family, Szpilman was able to escape deportation to Auschwitz.

This film is closely based on Szpilman’s autobiography and memoir of the same title. Its graphic depiction of Germans’ brutal treatment of Poles, especially Polish Jews, may be difficult for some students to watch. The amount of realistic historical detail and information included in the film is impressive, even daunting.

The film concludes with a powerful scene in which subtle historical details are used to show the coming Cold War. Despite including rich historical information, a film like The Pianist may not be used by many teachers because it is difficult and complex. However, the film is still very enticing because of how powerfully it fosters a sense of historical empathy in viewers as they watch actor Adrien Brody portray Szpilman’s struggle to stay alive. This film also demonstrates the role of music during the Holocaust. Film Rating: R

The Boy in Striped Pajamas

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, released in 2008 and based on a young-adult novel of the same title, is an entirely fictional Holocaust story that may be described as a sort of wishful history. The narrative revolves around the young son of a German concentration camp officer who befriends a Jewish boy in the camp whose prisoner outfit he interprets as striped pajamas. Together they discover shared humanity. This is an example of and educationally dangerous distortion of history. Not only is the plot not based on true events, most events could not have happened in the real Nazi camps.

Unfortunately, this movie has been widely shown in schools since its release. It is likely popular with teachers because of its more hopeful message of humanity. While it certainly draws the viewer into the story and creates a sense of empathy for the different characters, this fictional story’s few realistic representations – such the presence of antisemitism and the gas chambers at the Nazi death camp -are outweighed by its numerous, serious historical problems. Depictions of how Nazi camps operated, and the roles of officers, guards, prisoners, and local civilians are all heavily distorted. The hopeful message of shared humanity, while comforting, requires a completely imagined story to make it possible. Film Rating: PG-13.

The Book Thief

Adapted from a book authored by Marcus Zusak and released in 2013, The Book Thief follows the story of Liesel Meminger as she is adopted and starts her new life in a small German town. Her adoptive family appears to go along with Nazi ideologies, but they end up hiding a young Jewish man in their basement.

While this film is fictional, important historical events such as Kristallnacht and the public burning of (‘un-German,’ often Jewish) books are portrayed. This film is not based on a true story. Despite its fictional plot, the film does have merit. The story of young Liesel Meminger is relatable to students in a way that documentary or educational films typically are not. The film also shows that not all Germans were enthusiastic Nazis, and that some adapted to new antisemitic Nazi policies for their own security or promotion. However, the film does very little to portray the actual horrors of the Holocaust. Instead, it relies on the portrayal of small glimpses of the Holocaust, such as the fear of the young man in hiding or a group of Jewish people marched through the town. One aspect that the viewer does not become aware of until the end of the film, is that the film has been narrated by death. Film Rating: PG-13

Documentary or Educational Film

Educational film or “documentaries” are nonfiction motion-picture releases. They may be feature length (at least 90 minutes) or shorter for television. Documentaries tend to be favored by teachers because they claim to be informational, factual accounts or fact-based narratives (“docu-dramas”). Unlike popular film, documentary or educational film is not about fictionalized story lines or characters. As a media genre, documentaries are concerned with accurate and real information that are drawn from firsthand experiences and historical records. This does not mean, however that documentaries should not be evaluated. This genre of media can still contain biased perspectives or agendas and not all documentaries are factually reliable. Documentaries are often taken as a true representation of facts, so this type of media can be dangerous if not evaluated critically.

Since the Holocaust, many educational films and Holocaust documentaries have been made. Early documentaries helped the world awaken to the atrocities of the Holocaust. While many got a first view of the destruction in Europe from newsreels during the 1940s, this genre has grown and evolved. One important docudrama, made in the 1970s was NBC miniseries Holocaust. Watching this miniseries prompted US President Jimmy Carter to create the US Holocaust Commission (headed by Eli Wiesel) that ultimately established the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum (USHMM) (Fallace, 2008).

Documentary filmmaking about the Holocaust has been active in nations that are locations of significant Jewish migrant populations (the US, England, Canada, and Israel) and in nations that were sites of the Holocaust (Germany, Russia, Poland, and others). Holocaust documentaries range in length, with classics ranging from Resnais’ Night and Fog (1955, 32 minutes) and Landzmann’s 1985 epic Shoah (9.5 hours). Early and impactful documentaries were made by British and American allied forces upon their arrival at and liberation of Nazi concentration camps. Many shorter documentaries that compile footage and often include expert narrators have been made for classroom use. The ‘video toolbox’ from Echoes and Reflections is one example.

Documentaries, like all visual representations or propaganda, take a point of view that may impact historical memory. The settings and subjects, especially the range of those included or excluded, given voice or without voice, impact the narrative. Many documentaries, such as Night and Fog (1955), are among the visual representations that portray the ugly and shocking violence of Nazi mass atrocities. Some films simply depict the aftermath to show the scope of the violence; others interact with the subjects of the violence, both victims and perpetrators, often through interviews with survivors (a visual style that continues in the 21st century). One recent and notable documentary is Final Account (2020), which focuses on Germans who perpetrated or witnessed the Holocaust. Debates in both visual media and in memorial culture arise over the form and content of Holocaust representation, including the representation (or lack thereof) of Jewish people and subjects, but there remain many important subjects and themes represented by Holocaust documentary (Fallwell & Weiner, 2011). Some documentaries seek to humanize the Holocaust by remaining concerned with individual accounts. Issues of responsibility and moral transformation are sometimes the focus: Forgiving Dr. Mengele (2005) may lead the viewer to ask difficult questions, to simplify, or to over-generalize, but it does present different points of view about survivor forgiveness of Nazis like Dr. Mengele. It clearly positions Eva Kor’s decision to forgive her persecutor as a moral reckoning worth attention and perhaps emulation.

All documentaries should be previewed by educators before sharing with students and others. Because they can contain graphic descriptions of or images from the holocaust, USHMM recommends that Holocaust education should not begin before sixth grade. Recognizing the importance of Holocaust education, he Never Again Education Act and some state laws suggest or mandate that Holocaust education begin in sixth grade.

One Day in Auschwitz

One Day in Auschwitz, released in 2015, follows Holocaust survivor Kitty Hart-Moxon as she returns to Auschwitz with two high school aged girls and tells them her story. Kitty Hart-Moxon was sixteen years old when she was sent to Auschwitz with her mother. Hart-Moxon shares her experiences at Auschwitz, including her work in the Kanada, a codename for a warehouse full of Nazi stolen property (with vast stores of clothes and shoes. One of many forced laborers, she sorted the belongings taken from people deported to and often murdered in Auschwitz. From her workplace-in-confinement, she could see the gas chambers and witnessed Jewish partisan resistance in the form of a prisoner uprising.

The documentary strikes a balance between depicting the horrors of the Holocaust and being appropriate for younger audiences. Scenes that viewers may find difficult are tempered by sketches of what Kitty Hart-Moxon is describing. The fact that she was in Auschwitz when she was just sixteen is relatable for students, especially those in high school, making it easier for students to empathize with her and her experiences at Auschwitz. Rating: Not Rated

Forgiving Dr. Mengele

Released in 2005, Forgiving Dr. Mengele, is a unique documentary film. Eva Moses Kor, a Holocaust survivor and a twin who survived one of Dr. Mengele’s horrific human experiments, talks about her path to forgiving Dr. Mengele and others who took part in the war. While released in 2005, this documentary feels dated and may have less appeal to students. The tensions between Eva Kor and fellow survivors, however, is important for students to watch and offers some interesting discussion points. Many of the other Holocaust survivors who are featured in the documentary are opposed to Eva’s forgiveness of Dr. Mengele and other Nazis. Some argue that she had no right to forgive. The documentary also demonstrates how antisemitism has survived beyond WWII as Eva’s Candles Holocaust Museum was burned by an arsonist.

When watching this documentary be careful not to generalize based on Eva Kor’s experiences. The documentary is shown only from one perspective and can, at times, seem like it is discrediting perspectives other than Eva Kor’s. Forgiveness of war and other crimes, including mass atrocities, is a complex subject, perhaps a basis for advanced discussion of ethics. Rating: Not Rated

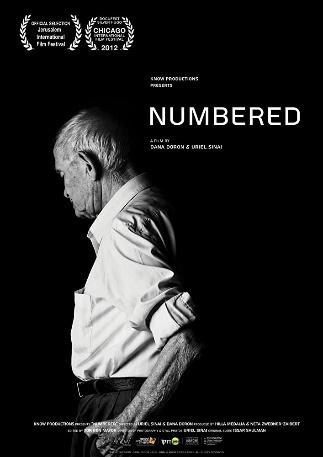

Numbered

Released in 2012, Numbered is an Israeli documentary in which survivors of the Holocaust recall their experiences. One innovative aspect of the documentary is that there is no narrator. The survivors simply tell their stories before, during, and after the war. The common thread through the documentary is the survivors’ discussion of the relationship they have with the number that was forcibly tattooed on their skin during the war. Tattooed numbers were used instead of names to identify and count prisoners at daily roll calls and other times. To learn more about these tattoos, visit the USHMM article on tattooed prisoner numbers. Some survivors in the film proudly still display their tattooed identity number, others hide it, and some had it removed.

The strength of this documentary is in the range of experiences of the Holocaust survivors. Each experienced the war in a different way, and each has dealt with their persecution in a unique way. This documentary does an excellent job of humanizing the Holocaust in a time when a lot of Holocaust education has been relegated to statistics. That humanization, however, may be difficult for some viewers as they hear the different stories. This documentary is best suited for older audiences. The documentary is in Hebrew, but English subtitles are available. Rating: Not Rated

Web Media

“Web media” chiefly consists of digital video productions that do not have physical or standard commercial distribution. They are usually shorter-length videos available on demand through streaming. The most widely used platform is YouTube, but there are now many other and specifically educational platforms, like Ted-Ed. This type of media is much newer than the other categories and was not widely available to the public before the 2010s. However, there has been an explosive growth in the amount of web video productions made and available, including on web media on historical topics. While the Holocaust is not yet a common topic for web media, this type of media is likely to become only more important in the future.

There are several barriers to creating web media about the Holocaust. One is the psychological difficulty of the horrors of the Holocaust. This can dissuade casual viewers. A second is the historical complexity of the Holocaust that makes it cognitively difficult (Walsh, Hicks, & VanHover, 2017) to condense and comprehend in short form. The YouTube channel Time Ghost History is an excellent source of high-quality videos on the era of the World Wars and the Cold War, yet some of their content on the Nazis and Holocaust have been restricted and not openly available to everyone everywhere.

A chief advantage of web media for learning about the past is its diversity. Unlike big-budget studio movies, or even major documentary films, making short videos is far easier, faster, and less expensive. As a result, there is a much wider and more diverse pool of creators for web media. More diverse creators mean more diverse and often specialized coverage of topics. Web videos tend to be much shorter and geared toward casual or “binge” viewing. While nothing today prevents creators from putting feature-length videos online, most web media are less than 30 minutes in length, and many are in the range of 5-15 minutes. A major drawback of using web media to learn about the Holocaust or any other historical topic is trustworthiness. Not all web media are historically accurate or produced by historically informed creators. With such a low barrier to entry, virtually anyone can make a historical video to share online worldwide without having any expertise. Since some web creators may be sloppy or have malicious intent (such as video denying the Holocaust), we must be careful and critical about what we are viewing and look carefully at the material, as well as the creator’s expertise or qualifications.

Crash Course

With more than 10 million subscribers, Crash Course is a very successful YouTube channel that offers a variety of concise, topical educational videos. Produced by Complexly (the team also responsible for the popular SciShow series), Crash Course began with videos on biology and history by the brothers Hank and John Green. It has since expanded into very diverse subjects. Initially teachers and schools were the target audience, but in recent years Crash Course videos have embraced a wider public audience interested in learning.

Complex productions are notable for their good visual quality and for being well-researched, which adds to the sense that Crash Course is trustworthy. Crash Course videos are still popular with teachers and generally liked by students because they are short (under 15 minutes), but still packed with information, and presented in a colorful, engaging “edutainment” style. History remains a staple of Crash Course, with its European History series reaching the era of WWII and the Holocaust in early 2020.

“Holocaust, Genocide, and Mass Murder of WWII” (Crash Course European History #40) reflects many of the challenges described above facing web media about the Holocaust. While still recognizably Crash Course, its tone and structure are noticeably different than other videos. At just under 14 minutes in length, significantly more time is spent in the introduction than other videos of the series. This is partly due to a discussion of antisemitism and difficult choices of video graphics that must be made in an episode about the Holocaust.

While the video still includes Crash Course’s jaunty title theme, the rest is subdued without the usual light humor and colorful pop-up graphics (only a few portraits of people are shown with playful coloration). Instead, most of the video’s backgrounds are period still photographs that were clearly chosen to be representative but not more disturbingly graphic than necessary. The video avoids Nazi imagery from the time except for what appears in the grainy black-and-white photos.

There are important missing issues (such as the impact of the death camps on Germany’s war effort) and missing details (such as the Jewish breakout at Sobibor), but the video still presents an impressive variety of complex historical information.

Conclusion

Modern media offer viewers more ways to visualize and learn about the Holocaust. However, visual narrative and representation create potential problems, too. Most people already understand that historical movies, by their nature, are at least fictionalized stories and not always factually reliable. Yet it is difficult for many viewers to sort out what elements in movies are accurate and what are imagined or distorted. This is especially problematic for Holocaust films, which may gain trust from viewers through their empathetic appeal. Documentary film is even more complex because its nonfiction format and tone can imply that it is objective history or at least presented from an unbiased perspective. It is important to understand that documentaries are made by people for particular purposes and still involve decisions about what historical information to portray and how. Web media is a growing, popular format, but the reliability of the information portrayed can be even more uncertain. Furthermore, limitations of YouTube as the dominant online platform may limit how much about the Holocaust is likely to be taught through web media. In every form of media, we should remember to critically evaluate what we are watching.

References

Baron, L. (2010). Film. In P. Hayes & J.K. Roth (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Holocaust Studies (pp. 444-460). Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211869.003.0030

Brownstein, R. (2020). Holocaust cinema complete: A history and analysis of 400 films, with a teacher guide. McFarland Books.

Eaglestone, R., & Langford, B. (Eds.). (2008). Teaching Holocaust literature and film. Palgrave Macmillan.

Fallace, T. D. (2008). The emergence of Holocaust education in American schools (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Fallwell, L., & Weiner, R. G. (2011). Holocaust Documentaries. In Friedman, J. C. (Ed.), The Routledge history of the Holocaust (pp. 452–463). Taylor & Francis Group.

Marcus, A. S., Metzger, S. A., Paxton, R. J., & Stoddard, J. D. (2018). Teaching history with film: Strategies for secondary social studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Marcus, Alan S. (2017). Teaching the Holocaust through film. Social Education, 81(3), 172-176.

Schweber, S. (2010). Education. In P. Hayes & J. K. Roth (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Holocaust Studies. Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211869.003.0046

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). (2022). USHMM Holocaust Encyclopedia

Walsh, B., Hicks, D., & van Hover, S. (2017). Difficult history means difficult questions: Using film to reveal the perspective of “the other’ in difficult history topics. In J. Stoddard, A. S. Marcus, & D. Hicks (Eds.), Teaching difficult history through film (pp. 17-36). Routledge.

A personal and sometimes unreasoned judgment. Bias is a synonym of prejudice, which means: (1) a preconceived judgment or opinion, or (2) an adverse opinion or leaning formed without just grounds or before sufficient knowledge. Merriam-Webster

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether nonfictional or fictional. Wikipedia

“Efforts to excuse or minimize the impact of the Holocaust or its principal elements,” including minimizing the number of victims, blaming Jews for genocide, casting the Holocaust as a positive event, or blurring or deflecting the responsibility for the establishment of concentration and death camps. IHRA.

Code name for storage facilities in Auschwitz; buildings were used to store stolen belongings of prisoners, mostly Jews who had been sent to the gas chamber on arrival. Wikipedia.