Private: Chapter Thirteen

Chemical Equilibria (13.1)

OpenStax

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the nature of equilibrium systems

- Explain the dynamic nature of a chemical equilibrium

The convention for writing chemical equations involves placing reactant formulas on the left side of a reaction arrow and product formulas on the right side. By this convention, and the definitions of “reactant” and “product,” a chemical equation represents the reaction in question as proceeding from left to right. Reversible reactions, however, may proceed in both forward (left to right) and reverse (right to left) directions. When the rates of the forward and reverse reactions are equal, the concentrations of the reactant and product species remain constant over time and the system is at equilibrium. The relative concentrations of reactants and products in equilibrium systems vary greatly; some systems contain mostly products at equilibrium, some contain mostly reactants, and some contain appreciable amounts of both.

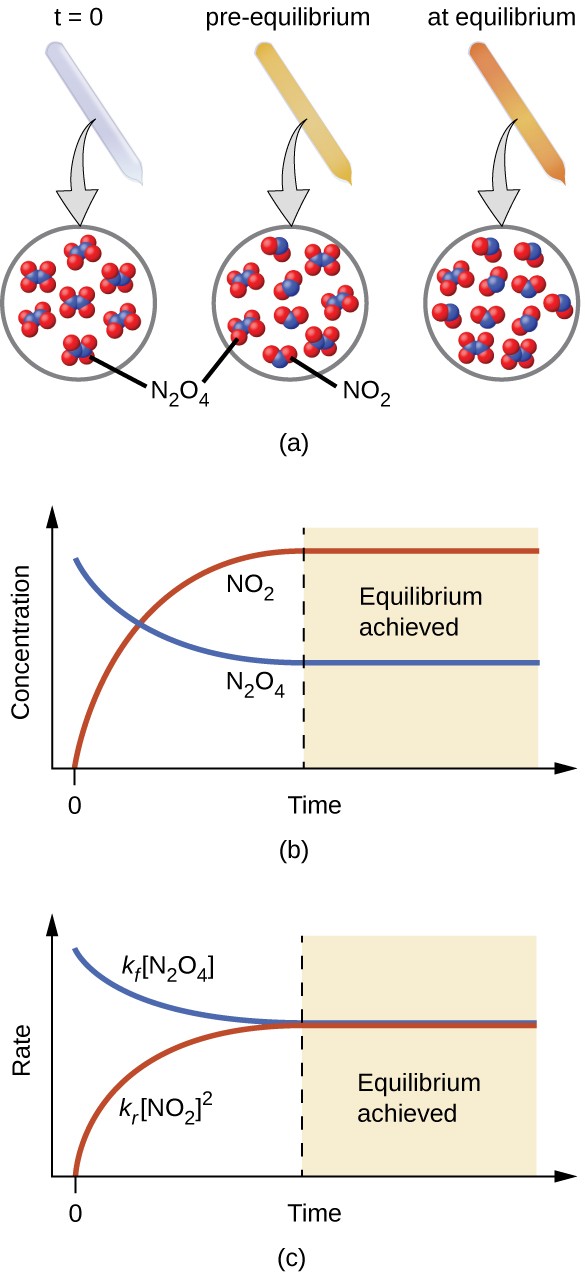

Figure 13.2 illustrates fundamental equilibrium concepts using the reversible decomposition of colorless dinitrogen tetroxide to yield brown nitrogen dioxide, an elementary reaction described by the equation:

N2 O4(g) ⇌ 2NO2(g)

Note that a special double arrow is used to emphasize the reversible nature of the reaction.

Figure 13.2 (a) A sealed tube containing colorless N2O4 darkens as it decomposes to yield brown NO2. (b) Changes in concentration over time as the decomposition reaction achieves equilibrium. (c) At equilibrium, the forward and reverse reaction rates are equal.

For this elementary process, rate laws for the forward and reverse reactions may be derived directly from the reaction stoichiometry:

rate f = k f [N−2 O4]

rate r = kr[NO2 ]2

As the reaction begins (t = 0), the concentration of the N2O4 reactant is finite and that of the NO2 product is zero, so the forward reaction proceeds at a finite rate while the reverse reaction rate is zero. As time passes, N−2O4 is consumed and its concentration falls, while NO2 is produced and its concentration increases (Figure 13.2 b). The decreasing concentration of the reactant slows the forward reaction rate, and the increasing product concentration speeds the reverse reaction rate (Figure 13.2 c). This process continues until the forward and reverse reaction rates

become equal, at which time the reaction has reached equilibrium, as characterized by constant concentrations of its reactants and products (shaded areas of Figure 13.2 b and Figure 13.2 c). It’s important to emphasize that chemical equilibria are dynamic; a reaction at equilibrium has not “stopped,” but is proceeding in the forward and reverse directions at the same rate. This dynamic nature is essential to understanding equilibrium behavior as discussed in this and subsequent chapters of the text.

Figure 13.3 A two-person juggling act illustrates the dynamic aspect of chemical equilibria. Each person is throwing and catching clubs at the same rate, and each holds a (approximately) constant number of clubs.

Physical changes, such as phase transitions, are also reversible and may establish equilibria. This concept was introduced in another chapter of this text through discussion of the vapor pressure of a condensed phase (liquid or solid). As one example, consider the vaporization of bromine:

Br2(l) ⇌ Br2(g)

When liquid bromine is added to an otherwise empty container and the container is sealed, the forward process depicted above (vaporization) will commence and continue at a roughly constant rate as long as the exposed surface area of the liquid and its temperature remain constant. As increasing amounts of gaseous bromine are produced, the rate of the reverse process (condensation) will increase until it equals the rate of vaporization and equilibrium is established. A photograph showing this phase transition equilibrium is provided in Figure 13.4.

Figure 13.4 A sealed tube containing an equilibrium mixture of liquid and gaseous bromine. (credit: http://images-of- elements.com/bromine.php)

Key Concepts and Summary

A reaction is at equilibrium when the amounts of reactants or products no longer change. Chemical equilibrium is a dynamic process, meaning the rate of formation of products by the forward reaction is equal to the rate at which the products re-form reactants by the reverse reaction.

Chemistry End of Chapter Exercises

- What does it mean to describe a reaction as “reversible”?

- When writing an equation, how is a reversible reaction distinguished from a nonreversible reaction?

- If a reaction is reversible, when can it be said to have reached equilibrium?

- Is a system at equilibrium if the rate constants of the forward and reverse reactions are equal?

- If the concentrations of products and reactants are equal, is the system at equilibrium?

Glossary

- equilibrium

- in chemical reactions, the state in which the conversion of reactants into products and the conversion of products back into reactants occur simultaneously at the same rate; state of balance

- reversible reaction

- chemical reaction that can proceed in both the forward and reverse directions under given conditions

Solutions

Answers to Chemistry End of Chapter Exercises

1. The reaction can proceed in both the forward and reverse directions.

3. When a system has reached equilibrium, no further changes in the reactant and product concentrations occur; the reactions continue to occur, but at equivalent rates.

5. The concept of equilibrium does not imply equal concentrations, though it is possible.