Private: Chapter Seventeen

Electrode and Cell Potentials (17.3)

OpenStax

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe and relate the definitions of electrode and cell potentials

- Interpret electrode potentials in terms of relative oxidant and reductant strengths

- Calculate cell potentials and predict redox spontaneity using standard electrode potentials

Unlike the spontaneous oxidation of copper by aqueous silver(I) ions described in section 17.2, immersing a copper wire in an aqueous solution of lead(II) ions yields no reaction. The two species, Ag+(aq) and Pb2+(aq), thus show a distinct difference in their redox activity towards copper: the silver ion spontaneously oxidized copper, but the lead ion did not. Electrochemical cells permit this relative redox activity to be quantified by an easily measured property, potential. This property is more commonly called voltage when referenced in regard to electrical applications, and it is a measure of energy accompanying the transfer of charge. Potentials are measured in the volt unit, defined as one joule of energy per one coulomb of charge, V = J/C.

When measured for purposes of electrochemistry, a potential reflects the driving force for a specific type of charge transfer process, namely, the transfer of electrons between redox reactants. Considering the nature of potential in this context, it is clear that the potential of a single half-cell or a single electrode can’t be measured; “transfer” of electrons requires both a donor and recipient, in this case a reductant and an oxidant, respectively. Instead, a half-cell potential may only be assessed relative to that of another half-cell. It is only the difference in potential between two half-cells that may be measured, and these measured potentials are called cell potentials, Ecell, defined as

Ecell = Ecathode − Eanode

where Ecathode and Eanode are the potentials of two different half-cells functioning as specified in the subscripts. As for other thermodynamic quantities, the standard cell potential, E°cell, is a cell potential measured when both half-cells are under standard-state conditions (1 M concentrations, 1 bar pressures, 298 K):

E°cell = E°cathode − E°anode

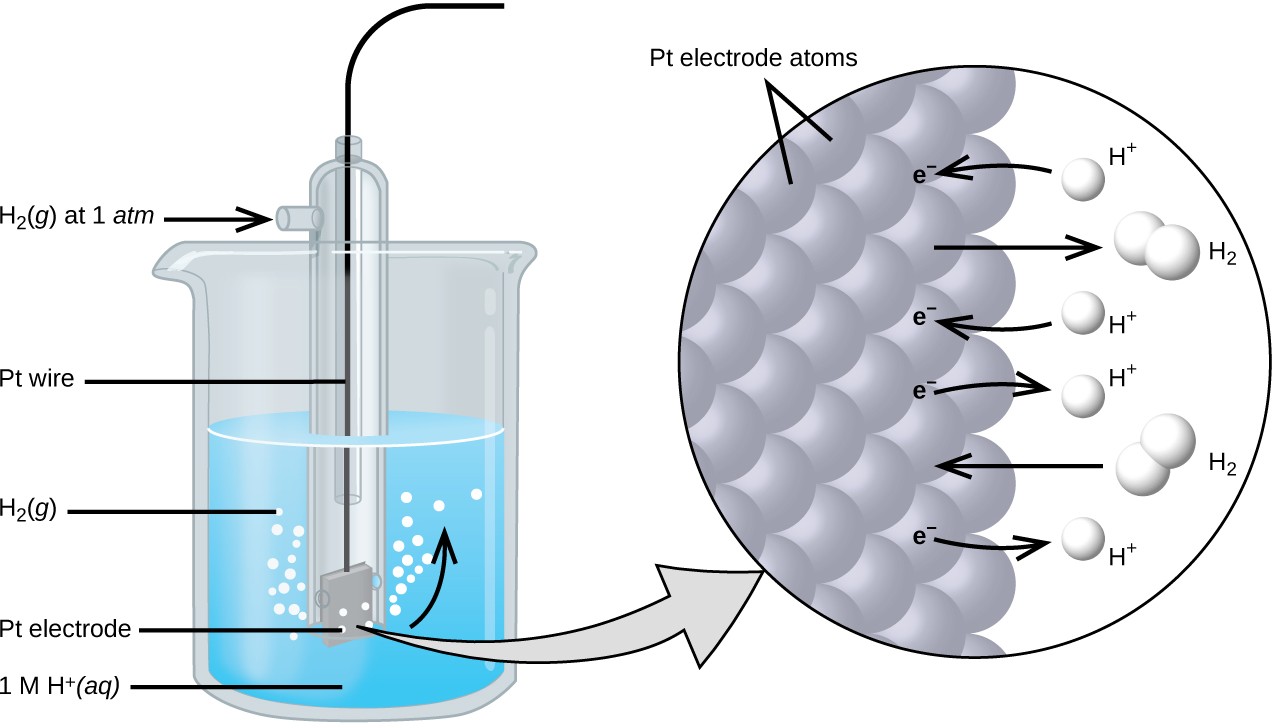

To simplify the collection and sharing of potential data for half-reactions, the scientific community has designated one particular half-cell to serve as a universal reference for cell potential measurements, assigning it a potential of exactly 0 V. This half-cell is the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) and it is based on half-reaction below:

2H+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ H2(g)

A typical SHE contains an inert platinum electrode immersed in precisely 1 M aqueous H+ and a stream of bubbling H2 gas at 1 bar pressure, all maintained at a temperature of 298 K (see Figure 17.5).

Figure 17.5 A standard hydrogen electrode (SHE).

The assigned potential of the SHE permits the definition of a conveniently measured potential for a single half-cell. The electrode potential (EX) for a half-cell X is defined as the potential measured for a cell comprised of X acting as cathode and the SHE acting as anode:

Ecell =EX − ESHE

ESHE = 0 V (defined)

Ecell = EX

When the half-cell X is under standard-state conditions, its potential is the standard electrode potential, E°X. Since the definition of cell potential requires the half-cells function as cathodes, these potentials are sometimes called standard reduction potentials.

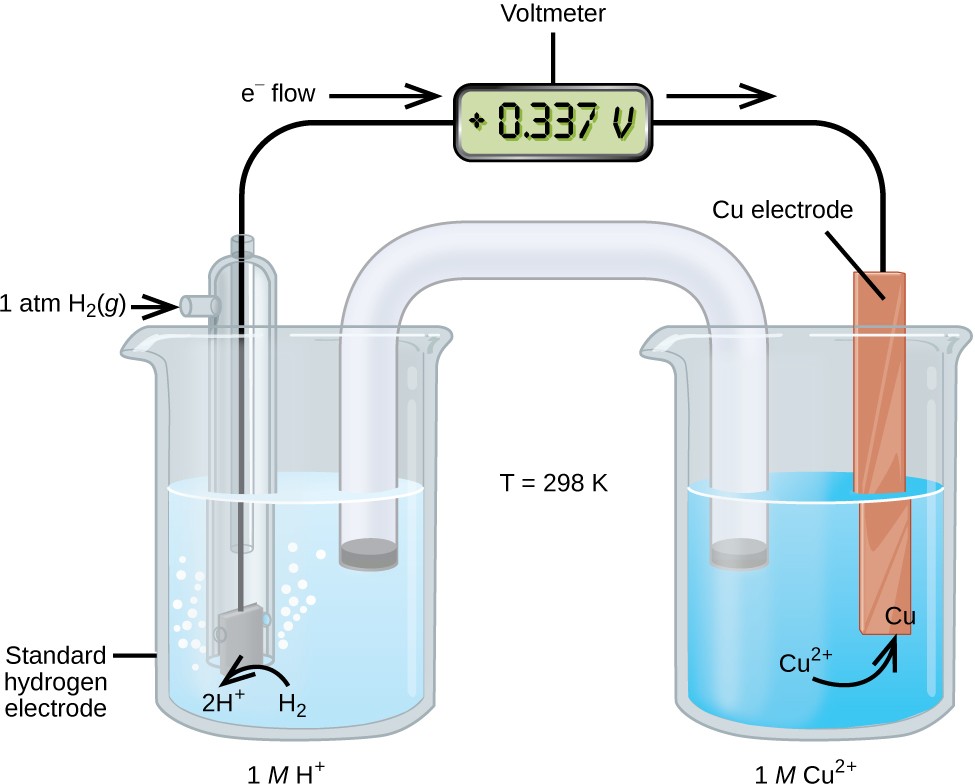

This approach to measuring electrode potentials is illustrated in Figure 17.6, which depicts a cell comprised of an SHE connected to a copper(II)/copper(0) half-cell under standard-state conditions. A voltmeter in the external circuit allows measurement of the potential difference between the two half-cells. Since the Cu half-cell is designated as the cathode in the definition of cell potential, it is connected to the red (positive) input of the voltmeter, while the designated SHE anode is connected to the black (negative) input. These connections insure that the sign of the measured potential will be consistent with the sign conventions of electrochemistry per the various definitions discussed above. A cell potential of +0.337 V is measured, and so

E° cell = E° Cu = +0.337 V

Tabulations of E° values for other half-cells measured in a similar fashion are available as reference literature to permit calculations of cell potentials and the prediction of the spontaneity of redox processes.

Figure 17.6 A cell permitting experimental measurement of the standard electrode potential for the half-reaction Cu2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Cu(s)

Table 17.1 provides a listing of standard electrode potentials for a selection of half-reactions in numerical order, and a more extensive alphabetical listing is given in Appendix L.

Selected Standard Reduction Potentials at 25 °C

|

Half-Reaction |

E° (V) |

|

F2(g) + 2e− ⟶ 2F−(aq) |

+2.866 |

|

PbO2(s) + SO4 2−(aq) + 4H+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ PbSO4(s) + 2H2 O(l) |

+1.69 |

|

MnO4 −(aq) + 8H+(aq) + 5e− ⟶ Mn2+(aq) + 4H2 O(l) |

+1.507 |

|

Au3+(aq) + 3e− ⟶ Au(s) |

+1.498 |

|

Cl2(g) + 2e− ⟶ 2Cl−(aq) |

+1.35827 |

|

O2(g) + 4H+(aq) + 4e− ⟶ 2H2 O(l) |

+1.229 |

|

Pt2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Pt(s) |

+1.20 |

|

Br2(aq) + 2e− ⟶ 2Br−(aq) |

+1.0873 |

|

Ag+(aq) + e− ⟶ Ag(s) |

+0.7996 |

|

Hg2 2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ 2Hg(l) |

+0.7973 |

|

Fe3+(aq) + e− ⟶ Fe2+(aq) |

+0.771 |

|

MnO4 −(aq) + 2H2 O(l) + 3e− ⟶ MnO2(s) + 4OH−(aq) |

+0.558 |

|

I2(s) + 2e− ⟶ 2I−(aq) |

+0.5355 |

|

NiO2(s) + 2H2 O(l) + 2e− ⟶ Ni(OH)2(s) + 2OH−(aq) |

+0.49 |

|

Cu2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Cu(s) |

+0.34 |

|

Hg2 Cl2(s) + 2e− ⟶ 2Hg(l) + 2Cl−(aq) |

+0.26808 |

|

AgCl(s) + e− ⟶ Ag(s) + Cl−(aq) |

+0.22233 |

|

Sn4+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Sn2+(aq) |

+0.151 |

|

2H+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ H2(g) |

0.00 |

|

Pb2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Pb(s) |

−0.1262 |

|

Sn2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Sn(s) |

−0.1375 |

|

Ni2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Ni(s) |

−0.257 |

|

Co2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Co(s) |

−0.28 |

|

PbSO4(s) + 2e− ⟶ Pb(s) + SO4 2−(aq) |

−0.3505 |

|

Cd2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Cd(s) |

−0.4030 |

|

Fe2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Fe(s) |

−0.447 |

|

Cr3+(aq) + 3e− ⟶ Cr(s) |

−0.744 |

|

Mn2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Mn(s) |

−1.185 |

|

Zn(OH)2(s) + 2e− ⟶ Zn(s) + 2OH−(aq) |

−1.245 |

|

Fe2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Fe(s) |

−0.447 |

|

Cr3+(aq) + 3e− ⟶ Cr(s) |

−0.744 |

|

Mn2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Mn(s) |

−1.185 |

|

Zn(OH)2(s) + 2e− ⟶ Zn(s) + 2OH−(aq) |

−1.245 |

|

Zn2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Zn(s) |

−0.7618 |

|

Al3+(aq) + 3e− ⟶ Al(s) |

−1.662 |

|

Mg2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Mg(s) |

−2.372 |

|

Na+(aq) + e− ⟶ Na(s) |

−2.71 |

|

Ca2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Ca(s) |

−2.868 |

|

Ba2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Ba(s) |

−2.912 |

|

K+(aq) + e− ⟶ K(s) |

−2.931 |

|

Li+(aq) + e− ⟶ Li(s) |

−3.04 |

Table 17.1

Example 17.4

Calculating Standard Cell Potentials

What is the standard potential of the galvanic cell shown in Figure 17.3?

Solution

The cell in Figure 17.3 is galvanic, the spontaneous cell reaction involving oxidation of its copper anode and reduction of silver(I) ions at its silver cathode:

cell reaction:Cu(s) + 2Ag+(aq) ⟶ Cu2+(aq) + 2Ag(s)

anode half-reaction:Cu(s) ⟶ Cu2+(aq) + 2e−

cathode half-reaction:2Ag+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ 2Ag(s)

The standard cell potential computed as

E° cell = E° cathode − E° anode

= E° Ag − E° Cu

= 0.7996 V − 0.34 V

= +0.46 V

Check Your Learning

What is the standard cell potential expected if the silver cathode half-cell in Figure 17.3 is replaced with a lead half-cell: Pb2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Pb(s) ?

Answer: −0. 47 V

Interpreting Electrode and Cell Potentials

Thinking carefully about the definitions of cell and electrode potentials and the observations of spontaneous redox change presented thus far, a significant relation is noted. The previous section described the spontaneous oxidation of copper by aqueous silver(I) ions, but no observed reaction with aqueous lead(II) ions. Results of the calculations in Example 17.4 have just shown the spontaneous process is described by a positive cell potential while the nonspontaneous process exhibits a negative cell potential. And so, with regard to the relative effectiveness (“strength”) with which aqueous Ag+ and Pb2+ ions oxidize Cu under standard conditions, the stronger oxidant is the one exhibiting the greater standard electrode potential, E°. Since by convention electrode potentials are for reduction processes, an increased value of E° corresponds to an increased driving force behind the reduction of the species (hence increased effectiveness of its action as an oxidizing agent on some other species). Negative values for electrode potentials are simply a consequence of assigning a value of 0 V to the SHE, indicating the reactant of the half-reaction is a weaker oxidant than aqueous hydrogen ions.

Applying this logic to the numerically ordered listing of standard electrode potentials in Table 17.1 shows this listing

to be likewise in order of the oxidizing strength of the half-reaction’s reactant species, decreasing from strongest oxidant (most positive E°) to weakest oxidant (most negative E°). Predictions regarding the spontaneity of redox reactions under standard state conditions can then be easily made by simply comparing the relative positions of their table entries. By definition, E°cell is positive when E°cathode > E°anode, and so any redox reaction in which the oxidant’s entry is above the reductant’s entry is predicted to be spontaneous.

Reconsideration of the two redox reactions in Example 17.4 provides support for this fact. The entry for the silver(I)/silver(0) half-reaction is above that for the copper(II)/copper(0) half-reaction, and so the oxidation of Cu by Ag+ is predicted to be spontaneous (E°cathode > E°anode and so E°cell > 0). Conversely, the entry for the lead(II)/lead(0) half-cell is beneath that for copper(II)/copper(0), and the oxidation of Cu by Pb2+ is nonspontaneous (E°cathode < E°anode and so E°cell < 0).

Recalling the chapter on thermodynamics, the spontaneities of the forward and reverse reactions of a reversible process show a reciprocal relationship: if a process is spontaneous in one direction, it is non-spontaneous in the opposite direction. As an indicator of spontaneity for redox reactions, the potential of a cell reaction shows a consequential relationship in its arithmetic sign. The spontaneous oxidation of copper by lead(II) ions is not observed,

Cu(s) + Pb2+(aq) ⟶ Cu2+(aq) + Pb(s) E°forward = −0.47 V (negative, non-spontaneous)

and so the reverse reaction, the oxidation of lead by copper(II) ions, is predicted to occur spontaneously:

Pb(s) + Cu2+(aq) ⟶ Pb2+(aq) + Cu(s) E°forward = +0.47 V (positive, spontaneous)

Note that reversing the direction of a redox reaction effectively interchanges the identities of the cathode and anode half-reactions, and so the cell potential is calculated from electrode potentials in the reverse subtraction order than that for the forward reaction. In practice, a voltmeter would report a potential of −0.47 V with its red and black inputs connected to the Pb and Cu electrodes, respectively. If the inputs were swapped, the reported voltage would be +0.47 V.

Diagonal Rule

The standard reduction potential table ordered in a descending order (such as Table 17.1) is a very useful tool to determine the spontaneity of a redox reaction. The diagonal rule states that, chemicals on the left side of the half reaction with a higher E° can spontaneously react with chemicals in the right side of the half reaction with a lower E°, under the standard conditions. The products will the the chemicals of the other sides of half reactions. For example:

I2(s) + 2e− ⟶ 2I−(aq) E° = +0.5355 V

Pb2+(aq) + 2e− ⟶ Pb(s) E° = −0.1262 V

According to the diagonal rule, the following reaction will happen spontaneously under standard conditions:

I2(s) + Pb(s) ⟶ 2I−(aq) + Pb2+(aq)

The standard cell potential is:

E° = (+0.5355 V) – (-0.1262 V) = 0.6617 V

When applying diagonal rule to determine the spontaneity of a redox reaction, please keep three things in mind:

- The standard reduction potential for half reactions has to be in a descending order.

- The direction of the diagonal is top-left and bottom-right.

- This rule only applies when chemicals are under standard conditions.

Example 17.5

Predicting Redox Spontaneity

Are aqueous iron(II) ions predicted to spontaneously oxidize elemental chromium under standard state conditions? Assume the half-reactions to be those available in Table 17.1.

Solution

Referring to the tabulated half-reactions, the redox reaction in question can be represented by the equations below:

Cr(s) + Fe2+(aq) ⟶ Cr3+(aq) + Fe(s)

The entry for the putative oxidant, Fe2+, appears above the entry for the reductant, Cr, and so a spontaneous reaction is predicted per the quick approach described above. Supporting this predication by calculating the standard cell potential for this reaction gives

E° cell = E° cathode − E° anode

= E° Fe(II) − E° Cr

= −0.447 V − −0.774 V = +0.297 V

The positive value for the standard cell potential indicates the process is spontaneous under standard state conditions.

Check Your Learning

Use the data in Table 17.1 to predict the spontaneity of the oxidation of bromide ion by molecular iodine under standard state conditions, supporting the prediction by calculating the standard cell potential for the reaction. Repeat for the oxidation of iodide ion by molecular bromine.

Answer:

I2(s) + 2Br−(aq) ⟶ 2I−(aq) + Br2(l) E ° cell = +0.5518 V (spontaneous)

Br2(s) + 2I−(aq) ⟶ 2Br−(aq) + I2(l) E ° cell = −0.5518 V (nonspontaneous)