Private: Chapter Fifteen

Lewis Acids and Bases (15.2)

OpenStax

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the Lewis model of acid-base chemistry

- Write equations for the formation of adducts and complex ions

- Perform equilibrium calculations involving formation constants

In 1923, G. N. Lewis proposed a generalized definition of acid-base behavior in which acids and bases are identified by their ability to accept or to donate a pair of electrons and form a coordinate covalent bond.

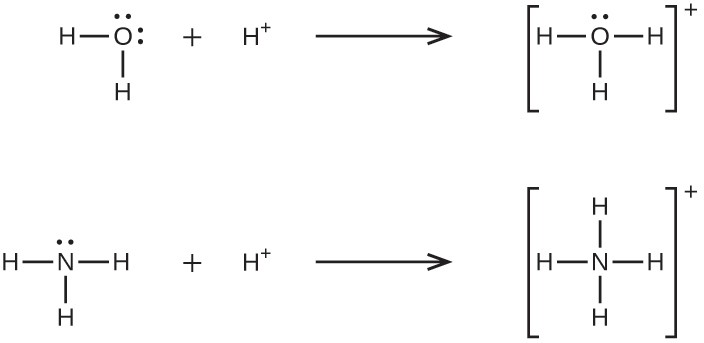

A coordinate covalent bond (or dative bond) occurs when one of the atoms in the bond provides both bonding electrons. For example, a coordinate covalent bond occurs when a water molecule combines with a hydrogen ion to form a hydronium ion. A coordinate covalent bond also results when an ammonia molecule combines with a hydrogen ion to form an ammonium ion. Both of these equations are shown here.

Reactions involving the formation of coordinate covalent bonds are classified as Lewis acid-base chemistry. The species donating the electron pair that compose the bond is a Lewis base, the species accepting the electron pair is a Lewis acid, and the product of the reaction is a Lewis acid-base adduct. As the two examples above illustrate, Brønsted-Lowry acid-base reactions represent a subcategory of Lewis acid reactions, specifically, those in which the acid species is H+. A few examples involving other Lewis acids and bases are described below.

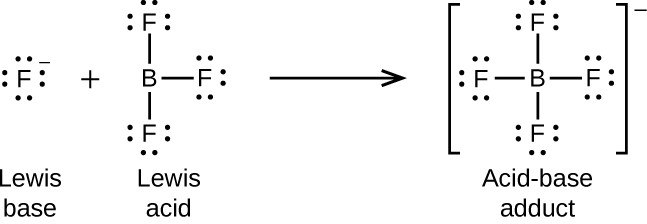

The boron atom in boron trifluoride, BF3, has only six electrons in its valence shell. Being short of the preferred octet, BF3 is a very good Lewis acid and reacts with many Lewis bases; a fluoride ion is the Lewis base in this reaction, donating one of its lone pairs:

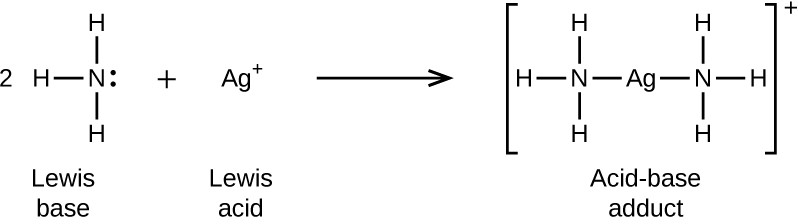

In the following reaction, each of two ammonia molecules, Lewis bases, donates a pair of electrons to a silver ion, the Lewis acid:

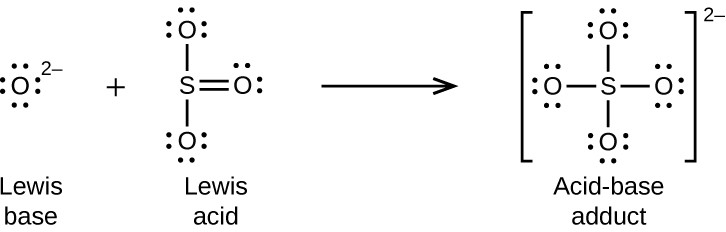

Nonmetal oxides act as Lewis acids and react with oxide ions, Lewis bases, to form oxyanions:

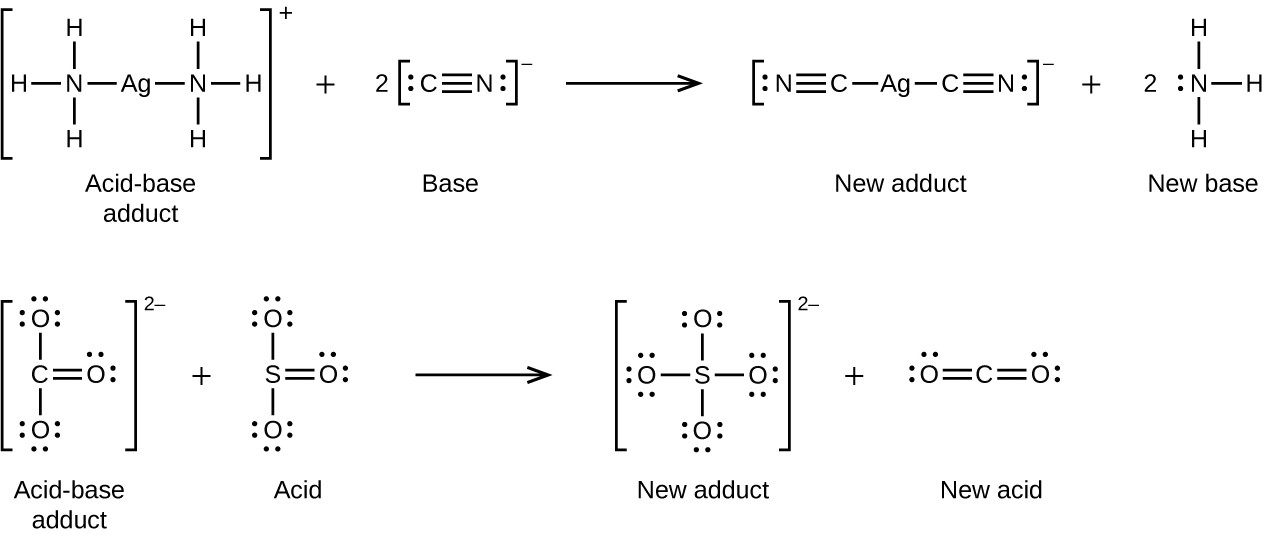

Many Lewis acid-base reactions are displacement reactions in which one Lewis base displaces another Lewis base from an acid-base adduct, or in which one Lewis acid displaces another Lewis acid:

Another type of Lewis acid-base chemistry involves the formation of a complex ion (or a coordination complex) comprising a central atom, typically a transition metal cation, surrounded by ions or molecules called ligands. These ligands can be neutral molecules like H2O or NH3, or ions such as CN– or OH–. Often, the ligands act as Lewis bases, donating a pair of electrons to the central atom. These types of Lewis acid-base reactions are examples of a broad sub-discipline called coordination chemistry—the topic of another chapter in this text.

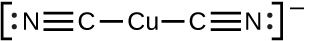

The equilibrium constant for the reaction of a metal ion with one or more ligands to form a coordination complex is called a formation constant (Kf) (sometimes called a stability constant). For example, the complex ion Cu(CN)2 −

is produced by the reaction

Cu+(aq) + 2CN−(aq) ⇌ Cu(CN)2 −(aq)

The formation constant for this reaction is

Kf = [latex]\frac{[Cu(CN)_{2} ^{-}]}{[Cu ^{+}][CN^{-}]^{2}}[/latex]

Alternatively, the reverse reaction (decomposition of the complex ion) can be considered, in which case the equilibrium constant is a dissociation constant (Kd). Per the relation between equilibrium constants for reciprocal

reactions described, the dissociation constant is the mathematical inverse of the formation constant, Kd = Kf–1. A tabulation of formation constants is provided in Appendix K.

As an example of dissolution by complex ion formation, let us consider what happens when we add aqueous ammonia to a mixture of silver chloride and water. Silver chloride dissolves slightly in water, giving a small concentration of Ag+ ([Ag+] = 1.3 × 10–5 M):

AgCl(s) ⇌ Ag+(aq) + Cl−(aq)

However, if NH3 is present in the water, the complex ion, Ag(NH3)2 +, can form according to the equation:

Example 15.14

Dissociation of a Complex Ion

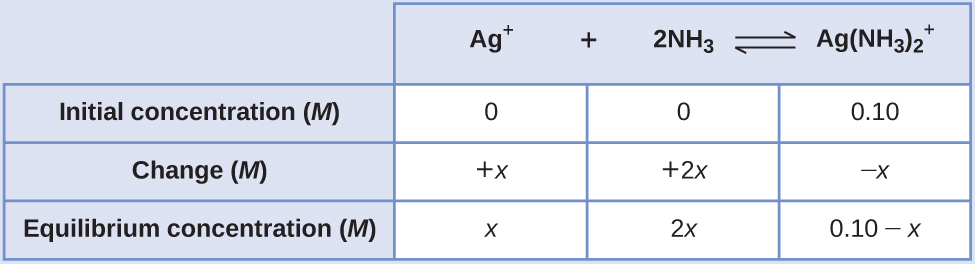

Calculate the concentration of the silver ion in a solution that initially is 0.10 M with respect to Ag(NH3)2 +.

Solution

Applying the standard ICE approach to this reaction yields the following:

Substituting these equilibrium concentration terms into the Kf expression gives

Kf = [latex]\frac{[Ag(NH_{3})_{2} ^{+}]}{[Ag ^{+}][NH_{3}]^{2}}[/latex]

1.7 × 107 =[latex]\frac{0.10 - x}{(x)(2x)^{2}}[/latex]

The very large equilibrium constant means the amount of the complex ion that will dissociate, x, will be very small. Assuming x << 0.1 permits simplifying the above equation:

1.7 x 107 = [latex]\frac{0.10}{(x)(2x)^{2}}[/latex]

x3 = [latex]\frac{0.10}{4(1.7 \times 10^{7})}[/latex] =1.5 x 10-9

x = [latex]^{3}\sqrt{1.5 \times 10^{-9}}[/latex] = 1.1 x 10-3

Because only 1.1% of the Ag(NH3)2 + dissociates into Ag+ and NH3, the assumption that x is small is justified.

Using this value of x and the relations in the above ICE table allows calculation of all species’ equilibrium concentrations:

[Ag+] = 0 + x = 1.1 × 10−3 M

[NH3] = 0 + 2x = 2.2 × 10−3 M

[Ag(NH3)2 +] = 0.10 − x = 0.10 − 0.0011 = 0.099

The concentration of free silver ion in the solution is 0.0011 M.

Check Your Learning

Calculate the silver ion concentration, [Ag+], of a solution prepared by dissolving 1.00 g of AgNO3 and 10.0 g of KCN in sufficient water to make 1.00 L of solution. (Hint (see the video below): Because Kf is very large, assume the reaction goes to completion then calculate the [Ag+] produced by dissociation of the complex.)

The following Youtube video will help you to better understand the "hint" in the Check Your Learning question above.

Answer: 2.5 × 10–22 M