Chapter One

Phases and Classification of Matter (1.2)

Phases and Classification of Matter

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the basic properties of each physical state of matter: solid, liquid, and gas

- Distinguish between mass and weight

- Apply the law of conservation of matter

- Classify matter as an element, compound, homogeneous mixture, or heterogeneous mixture with regard to its physical state and composition

- Define and give examples of atoms and molecules

Matter is defined as anything that occupies space and has mass, and it is all around us. Solids and liquids are more obviously matter: We can see that they take up space, and their weight tells us that they have mass. Gases are also

matter; if gases did not take up space, a balloon would not inflate (increase its volume) when filled with gas.

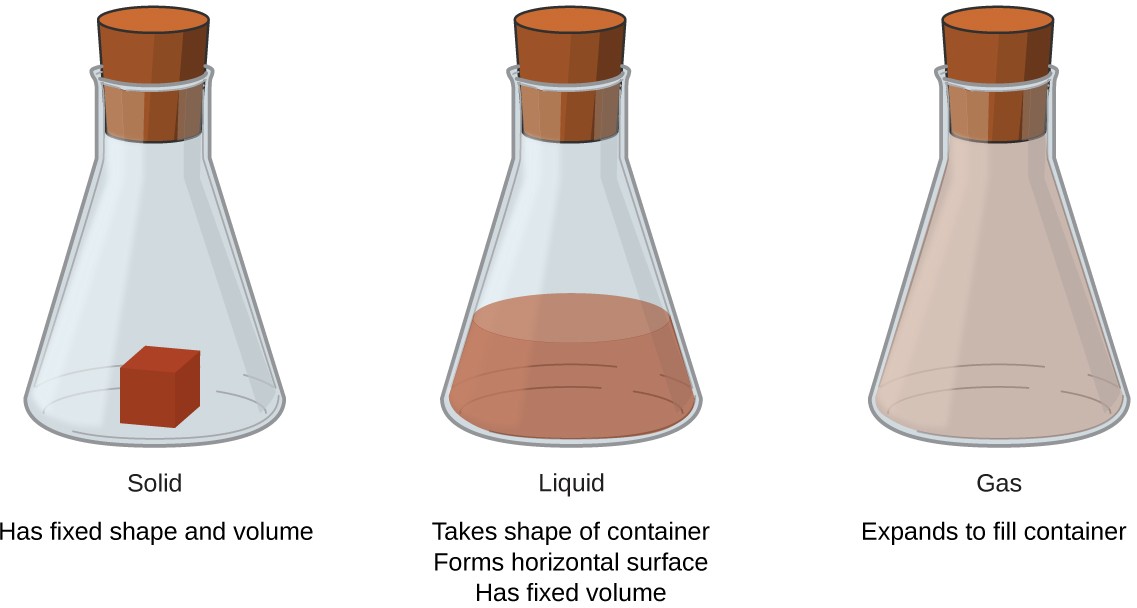

Solids, liquids, and gases are the three states of matter commonly found on earth (Figure 1.6). A solid is rigid and possesses a definite shape. A liquid flows and takes the shape of its container, except that it forms a flat or slightly curved upper surface when acted upon by gravity. (In zero gravity, liquids assume a spherical shape.) Both liquid and solid samples have volumes that are very nearly independent of pressure. A gas takes both the shape and volume of its container.

A fourth state of matter, plasma, occurs naturally in the interiors of stars. A plasma is a gaseous state of matter that contains appreciable numbers of electrically charged particles (Figure 1.7). The presence of these charged particles imparts unique properties to plasmas that justify their classification as a state of matter distinct from gases. In addition to stars, plasmas are found in some other high-temperature environments (both natural and man-made), such as lightning strikes, certain television screens, and specialized analytical instruments used to detect trace amounts of metals.

Link to LearningIn a tiny cell in a plasma television, the plasma emits ultraviolet light, which in turn causes the display at that location to appear a specific color. The composite of these tiny dots of color makes up the image that you see. Watch this video (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/16plasma) to learn more about plasma and theplaces you encounter it.

Some samples of matter appear to have properties of solids, liquids, and/or gases at the same time. This can occur when the sample is composed of many small pieces. For example, we can pour sand as if it were a liquid because it is composed of many small grains of solid sand. Matter can also have properties of more than one state when it is a mixture, such as with clouds. Clouds appear to behave somewhat like gases, but they are actually mixtures of air (gas) and tiny particles of water (liquid or solid).

The mass of an object is a measure of the amount of matter in it. One way to measure an object’s mass is to measure the force it takes to accelerate the object. It takes much more force to accelerate a car than a bicycle because the car has much more mass. A more common way to determine the mass of an object is to use a balance to compare its mass with a standard mass.

Although weight is related to mass, it is not the same thing. Weight refers to the force that gravity exerts on an object. This force is directly proportional to the mass of the object. The weight of an object changes as the force of gravity changes, but its mass does not. An astronaut’s mass does not change just because she goes to the moon. But her weight on the moon is only one-sixth her earth-bound weight because the moon’s gravity is only one-sixth that of the earth’s. She may feel “weightless” during her trip when she experiences negligible external forces (gravitational or any other), although she is, of course, never “massless.”

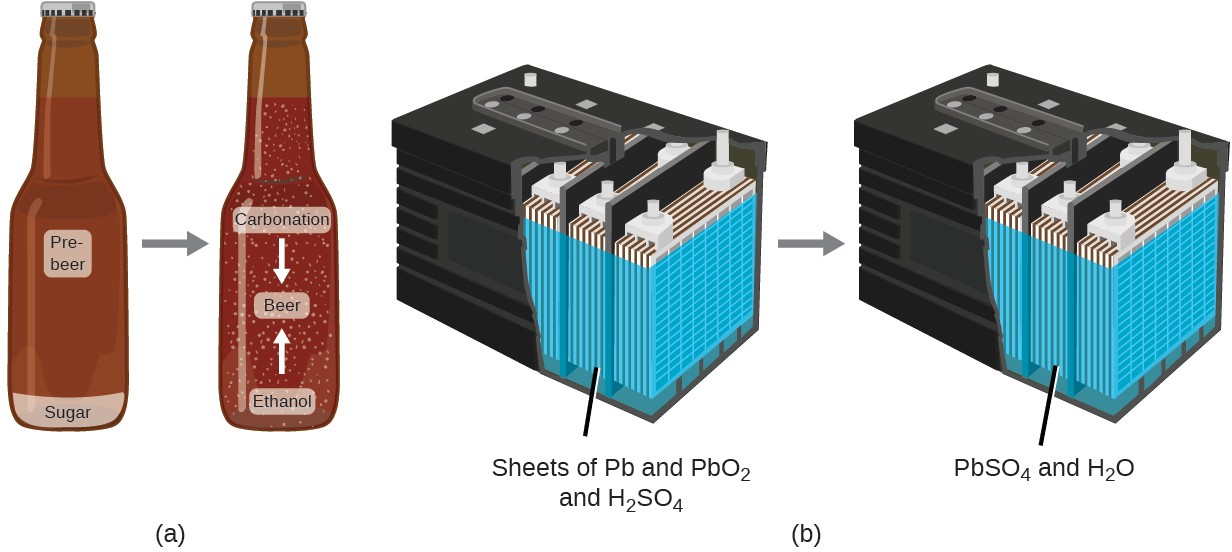

The law of conservation of matter summarizes many scientific observations about matter: It states that there is no detectable change in the total quantity of matter present when matter converts from one type to another (a chemical change) or changes among solid, liquid, or gaseous states (a physical change). Brewing beer and the operation of batteries provide examples of the conservation of matter (Figure 1.8). During the brewing of beer, the ingredients (water, yeast, grains, malt, hops, and sugar) are converted into beer (water, alcohol, carbonation, and flavoring substances) with no actual loss of substance. This is most clearly seen during the bottling process, when glucose turns into ethanol and carbon dioxide, and the total mass of the substances does not change. This can also be seen in a

lead-acid car battery: The original substances (lead, lead oxide, and sulfuric acid), which are capable of producing electricity, are changed into other substances (lead sulfate and water) that do not produce electricity, with no change in the actual amount of matter.

Although this conservation law holds true for all conversions of matter, convincing examples are few and far between because, outside of the controlled conditions in a laboratory, we seldom collect all of the material that is produced during a particular conversion. For example, when you eat, digest, and assimilate food, all of the matter in the original food is preserved. But because some of the matter is incorporated into your body, and much is excreted as various types of waste, it is challenging to verify by measurement.

Classifying Matter

Matter can be classified into several categories. Two broad categories are mixtures and pure substances. A pure substance has a constant composition. All specimens of a pure substance have exactly the same makeup and properties. Any sample of sucrose (table sugar) consists of 42.1% carbon, 6.5% hydrogen, and 51.4% oxygen by mass. Any sample of sucrose also has the same physical properties, such as melting point, color, and sweetness, regardless of the source from which it is isolated.

Pure substances may be divided into two classes: elements and compounds. Pure substances that cannot be broken down into simpler substances by chemical changes are called elements. Iron, silver, gold, aluminum, sulfur, oxygen, and copper are familiar examples of the more than 100 known elements, of which about 90 occur naturally on the earth, and two dozen or so have been created in laboratories.

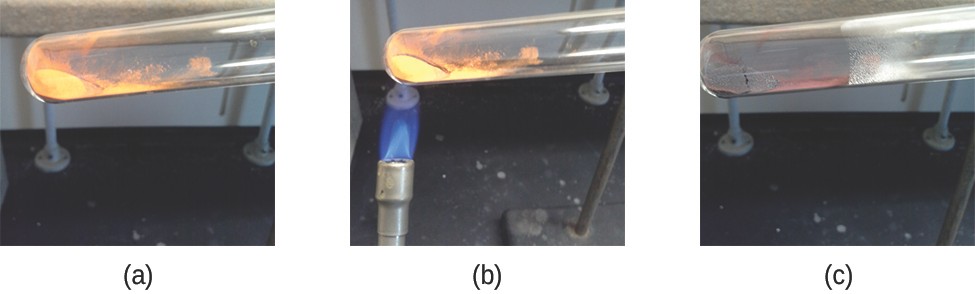

Pure substances that can be broken down by chemical changes are called compounds. This breakdown may produce either elements or other compounds, or both. Mercury(II) oxide, an orange, crystalline solid, can be broken down by heat into the elements mercury and oxygen (Figure 1.9). When heated in the absence of air, the compound sucrose is broken down into the element carbon and the compound water. (The initial stage of this process, when the sugar is turning brown, is known as caramelization—this is what imparts the characteristic sweet and nutty flavor to caramel apples, caramelized onions, and caramel). Silver(I) chloride is a white solid that can be broken down into its elements, silver and chlorine, by absorption of light. This property is the basis for the use of this compound in photographic

films and photochromic eyeglasses (those with lenses that darken when exposed to light).

Link to LearningMany compounds break down when heated. This site (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/16mercury) shows the breakdown of mercury oxide, HgO. You can also view an example of the photochemical decomposition of silver chloride (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/16silvchloride) (AgCl), the basis ofearly photography.

The properties of combined elements are different from those in the free, or uncombined, state. For example, white crystalline sugar (sucrose) is a compound resulting from the chemical combination of the element carbon, which is a black solid in one of its uncombined forms, and the two elements hydrogen and oxygen, which are colorless gases when uncombined. Free sodium, an element that is a soft, shiny, metallic solid, and free chlorine, an element that is a yellow-green gas, combine to form sodium chloride (table salt), a compound that is a white, crystalline solid.

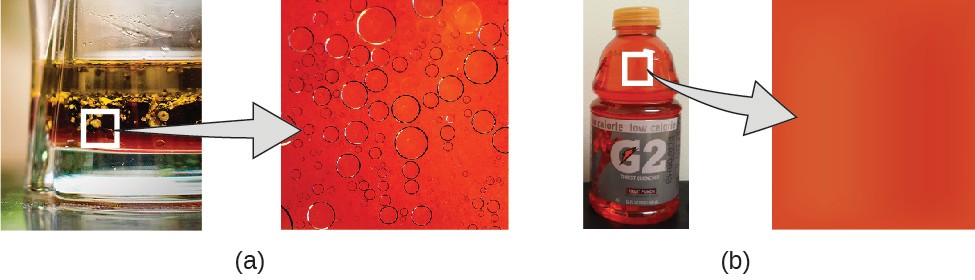

A mixture is composed of two or more types of matter that can be present in varying amounts and can be separated by physical changes, such as evaporation (you will learn more about this later). A mixture with a composition that varies from point to point is called a heterogeneous mixture. Italian dressing is an example of a heterogeneous mixture (Figure 1.10). Its composition can vary because it may be prepared from varying amounts of oil, vinegar, and herbs. It is not the same from point to point throughout the mixture—one drop may be mostly vinegar, whereas a different drop may be mostly oil or herbs because the oil and vinegar separate and the herbs settle. Other examples of heterogeneous mixtures are chocolate chip cookies (we can see the separate bits of chocolate, nuts, and cookie dough) and granite (we can see the quartz, mica, feldspar, and more).

A homogeneous mixture, also called a solution, exhibits a uniform composition and appears visually the same throughout. An example of a solution is a sports drink, consisting of water, sugar, coloring, flavoring, and electrolytes mixed together uniformly (Figure 1.10). Each drop of a sports drink tastes the same because each drop contains the same amounts of water, sugar, and other components. Note that the composition of a sports drink can vary—it could be made with somewhat more or less sugar, flavoring, or other components, and still be a sports drink. Other examples of homogeneous mixtures include air, maple syrup, gasoline, and a solution of salt in water.

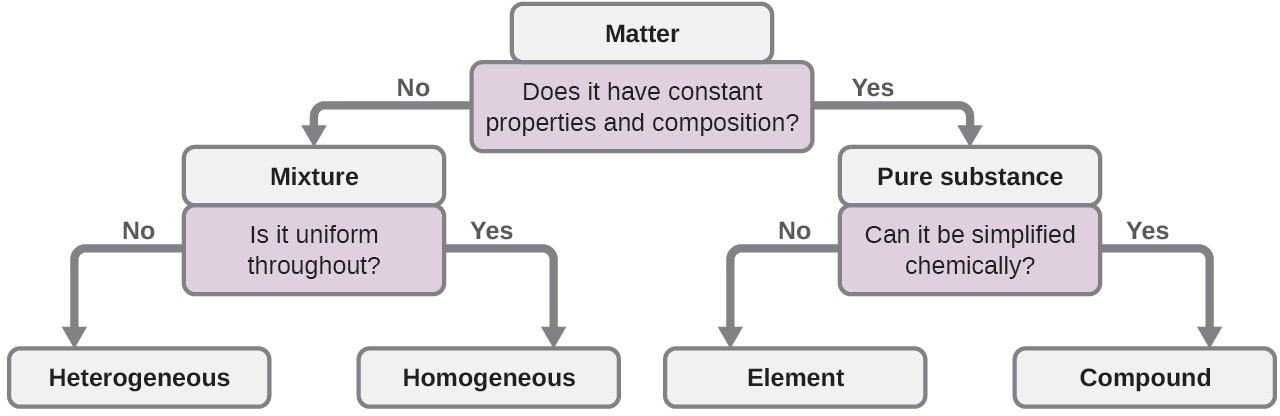

Although there are just over 100 elements, tens of millions of chemical compounds result from different combinations of these elements. Each compound has a specific composition and possesses definite chemical and physical properties that distinguish it from all other compounds. And, of course, there are innumerable ways to combine elements and compounds to form different mixtures. A summary of how to distinguish between the various major classifications of matter is shown in (Figure 1.11).

Eleven elements make up about 99% of the earth’s crust and atmosphere (Table 1.1). Oxygen constitutes nearly one- half and silicon about one-quarter of the total quantity of these elements. A majority of elements on earth are found in chemical combinations with other elements; about one-quarter of the elements are also found in the free state.

|

Element |

Symbol |

Percent Mass |

|---|---|---|

|

oxygen |

O |

49.20 |

|

chlorine |

Cl |

0.19 |

|

silicon |

Si |

25.67 |

|

phosphorus |

P |

0.11 |

|

aluminum |

Al |

7.50 |

|

manganese |

Mn |

0.09 |

|

Element |

Symbol |

Percent Mass |

|---|---|---|

|

iron |

Fe |

4.71 |

|

carbon |

C |

0.08 |

|

calcium |

Ca |

3.39 |

|

sulfur |

S |

0.06 |

|

sodium |

Na |

2.63 |

|

barium |

Ba |

0.04 |

|

potassium |

K |

2.40 |

|

nitrogen |

N |

0.03 |

|

magnesium |

Mg |

1.93 |

|

fluorine |

F |

0.03 |

|

hydrogen |

H |

0.87 |

|

strontium |

Sr |

0.02 |

|

titanium |

Ti |

0.58 |

|

all others |

– |

0.47 |

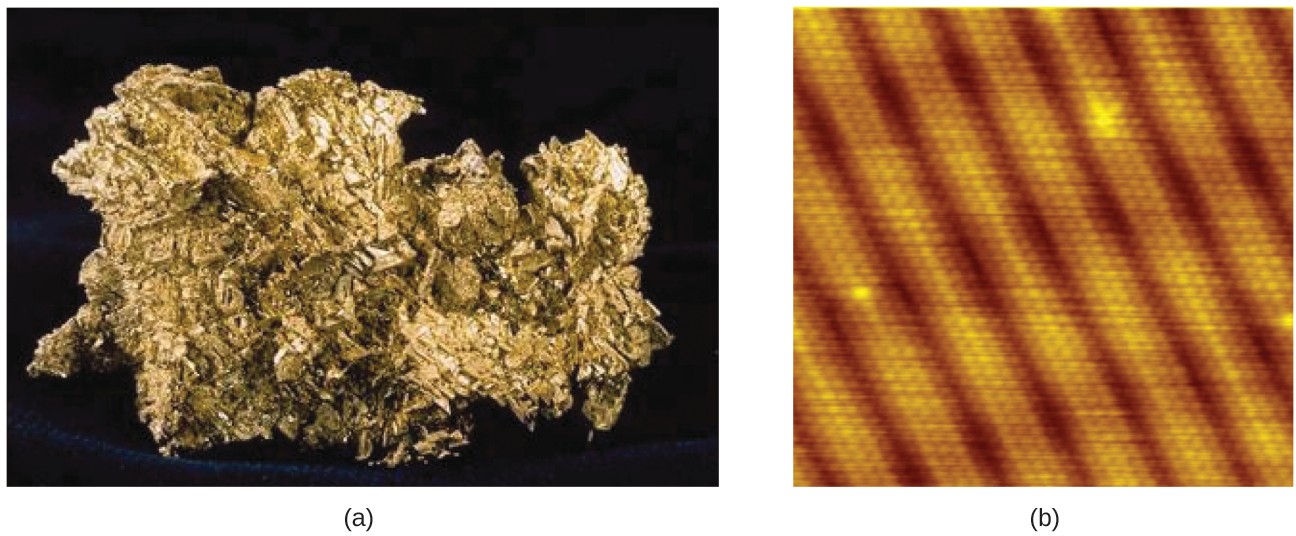

Table 1.2 Atoms and MoleculesAn atom is the smallest particle of an element that has the properties of that element and can enter into a chemical combination. Consider the element gold, for example. Imagine cutting a gold nugget in half, then cutting one of the halves in half, and repeating this process until a piece of gold remained that was so small that it could not be cut in half (regardless of how tiny your knife may be). This minimally sized piece of gold is an atom (from the Greek atomos, meaning “indivisible”) (Figure 1.12). This atom would no longer be gold if it were divided any further.

The first suggestion that matter is composed of atoms is attributed to the Greek philosophers Leucippus and Democritus, who developed their ideas in the 5th century BCE. However, it was not until the early nineteenth century that John Dalton (1766–1844), a British schoolteacher with a keen interest in science, supported this hypothesis with quantitative measurements. Since that time, repeated experiments have confirmed many aspects of this hypothesis, and it has become one of the central theories of chemistry. Other aspects of Dalton’s atomic theory are still used but with minor revisions (details of Dalton’s theory are provided in the chapter on atoms and molecules).An atom is so small that its size is difficult to imagine. One of the smallest things we can see with our unaided eye is a single thread of a spider web: These strands are about 1/10,000 of a centimeter (0.0001 cm) in diameter. Although the cross-section of one strand is almost impossible to see without a microscope, it is huge on an atomic scale. A single carbon atom in the web has a diameter of about 0.000000015 centimeter, and it would take about 7000 carbon atoms to span the diameter of the strand. To put this in perspective, if a carbon atom were the size of a dime, the cross-section of one strand would be larger than a football field, which would require about 150 million carbon atom “dimes” to cover it. (Figure 1.13) shows increasingly close microscopic and atomic-level views of ordinary cotton.

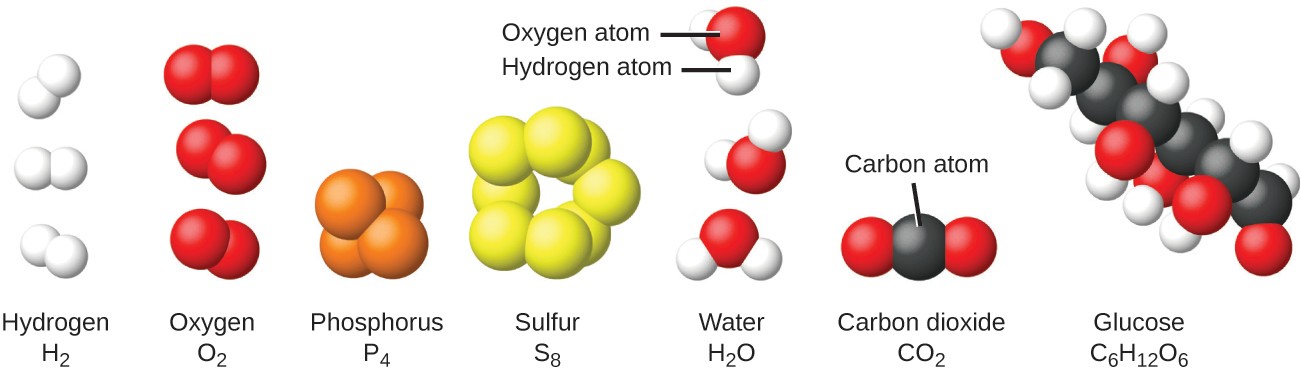

An atom is so light that its mass is also difficult to imagine. A billion lead atoms (1,000,000,000 atoms) weigh about3 × 10−13 grams, a mass that is far too light to be weighed on even the world’s most sensitive balances. It would require over 300,000,000,000,000 lead atoms (300 trillion, or 3 × 1014) to be weighed, and they would weigh only 0.0000001 gram.It is rare to find collections of individual atoms. Only a few elements, such as the gases helium, neon, and argon, consist of a collection of individual atoms that move about independently of one another. Other elements, such as the gases hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and chlorine, are composed of units that consist of pairs of atoms (Figure 1.14). One form of the element phosphorus consists of units composed of four phosphorus atoms. The element sulfur exists in various forms, one of which consists of units composed of eight sulfur atoms. These units are called molecules. A molecule consists of two or more atoms joined by strong forces called chemical bonds. The atoms in a molecule move around as a unit, much like the cans of soda in a six-pack or a bunch of keys joined together on a single key ring. A molecule may consist of two or more identical atoms, as in the molecules found in the elements hydrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, or it may consist of two or more different atoms, as in the molecules found in water. Each water molecule is a unit that contains two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Each glucose molecule is a unit that contains 6 carbon atoms, 12 hydrogen atoms, and 6 oxygen atoms. Like atoms, molecules are incredibly small and light. If an ordinary glass of water were enlarged to the size of the earth, the water molecules inside it would be about the size of golf balls.

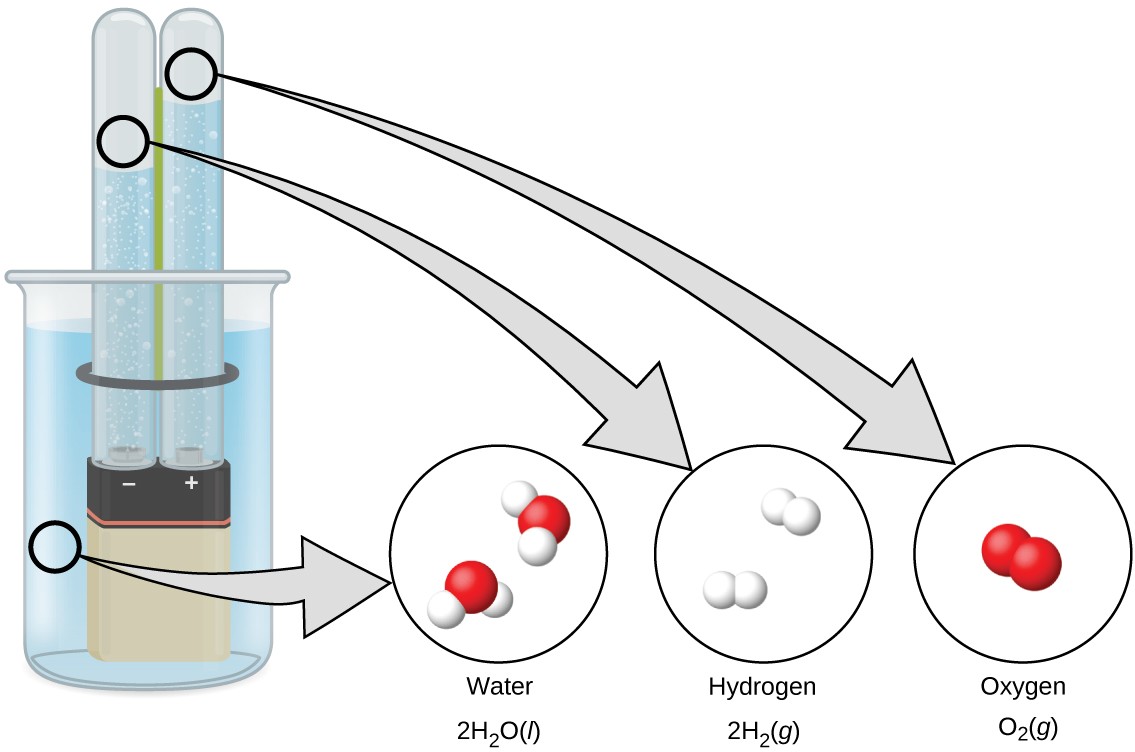

Chemistry in Everyday LifeDecomposition of Water / Production of HydrogenWater consists of the elements hydrogen and oxygen combined in a 2 to 1 ratio. Water can be broken down into hydrogen and oxygen gases by the addition of energy. One way to do this is with a battery or power supply, as shown in (Figure 1.15).

The breakdown of water involves a rearrangement of the atoms in water molecules into different molecules, each composed of two hydrogen atoms and two oxygen atoms, respectively. Two water molecules form one oxygen molecule and two hydrogen molecules. The representation for what occurs,2H2 O(l) ⟶ 2H2(g) + O2(g), will be explored in more depth in later chapters.The two gases produced have distinctly different properties. Oxygen is not flammable but is required for combustion of a fuel, and hydrogen is highly flammable and a potent energy source. How might this knowledge be applied in our world? One application involves research into more fuel-efficient transportation. Fuel-cell vehicles (FCV) run on hydrogen instead of gasoline (Figure 1.16). They are more efficient than vehicles with internal combustion engines, are nonpolluting, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, making us less dependent on fossil fuels. FCVs are not yet economically viable, however, and current hydrogen production depends on natural gas. If we can develop a process to economically decompose water, or produce hydrogen in another environmentally sound way, FCVs may be the way of the future.

Chemistry in Everyday LifeChemistry of Cell PhonesImagine how different your life would be without cell phones (Figure 1.17) and other smart devices. Cell phones are made from numerous chemical substances, which are extracted, refined, purified, and assembled using an extensive and in-depth understanding of chemical principles. About 30% of the elements that are found in nature are found within a typical smart phone. The case/body/frame consists of a combination of sturdy, durable polymers composed primarily of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen [acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and polycarbonate thermoplastics], and light, strong, structural metals, such as aluminum, magnesium, and iron. The display screen is made from a specially toughened glass (silica glass strengthened by the addition of aluminum, sodium, and potassium) and coated with a material to make it conductive (such as indium tin oxide). The circuit board uses a semiconductor material (usually silicon); commonly used metals like copper, tin, silver, and gold; and more unfamiliar elements such as yttrium, praseodymium, and gadolinium. The battery relies upon lithium ions and a variety of other materials, including iron, cobalt, copper, polyethylene oxide, and polyacrylonitrile.