Private: Chapter Fourteen

Relative Strengths of Acids and Bases (14.3)

OpenStax

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Assess the relative strengths of acids and bases according to their ionization constants

- Rationalize trends in acid–base strength in relation to molecular structure

- Carry out equilibrium calculations for weak acid–base systems

Acid and Base Ionization Constants

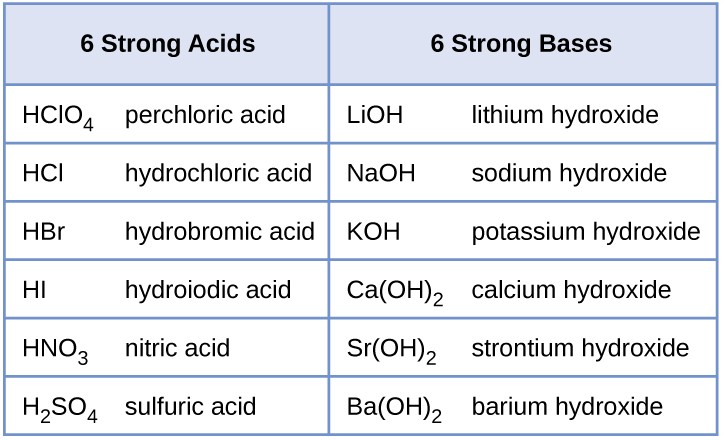

The relative strength of an acid or base is the extent to which it ionizes when dissolved in water. If the ionization reaction is essentially complete, the acid or base is termed strong; if relatively little ionization occurs, the acid or base is weak. As will be evident throughout the remainder of this chapter, there are many more weak acids and bases than strong ones. The most common strong acids and bases are listed in Figure 14.6.

Figure 14.6 Some of the common strong acids and bases are listed here.

The relative strengths of acids may be quantified by measuring their equilibrium constants in aqueous solutions. In solutions of the same concentration, stronger acids ionize to a greater extent, and so yield higher concentrations of hydronium ions than do weaker acids. The equilibrium constant for an acid is called the acid-ionization constant, Ka. For the reaction of an acid HA:

HA(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + A−(aq),

the acid ionization constant is written

Ka = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][A^{-}]}{[HA]}[/latex]

where the concentrations are those at equilibrium. Although water is a reactant in the reaction, it is the solvent as well, so we do not include [H2O] in the equation. The larger the Ka of an acid, the larger the concentration of H3 O+ and A− relative to the concentration of the nonionized acid, HA, in an equilibrium mixture, and the stronger the acid. An

acid is classified as “strong” when it undergoes complete ionization, in which case the concentration of HA is zero and the acid ionization constant is immeasurably large (Ka ≈ ∞). Acids that are partially ionized are called “weak,” and their acid ionization constants may be experimentally measured. A table of ionization constants for weak acids is provided in Appendix H.

To illustrate this idea, three acid ionization equations and Ka values are shown below. The ionization constants increase from first to last of the listed equations, indicating the relative acid strength increases in the order CH3CO2H < HNO2 < HSO4 − :

CH3 CO2 H(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + CH3CO2 −(aq) Ka = 1.8 × 10−5

HNO2(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + NO2 −(aq) Ka = 4.6 × 10−4

HSO4 −(aq) + H2O(aq) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + SO4 2−(aq) Ka = 1.2 × 10−2

Another measure of the strength of an acid is its percent ionization. The percent ionization of a weak acid is defined in terms of the composition of an equilibrium mixture:

% ionization = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}]_{eq}}{[HA]_{0}} \times 100[/latex]

where the numerator is equivalent to the concentration of the acid's conjugate base (per stoichiometry, [A−] = [H3O+]). Unlike the Ka value, the percent ionization of a weak acid varies with the initial concentration of acid, typically decreasing as concentration increases. Equilibrium calculations of the sort described later in this chapter can be used to confirm this behavior.

Example 14.7

Calculation of Percent Ionization from pH

Calculate the percent ionization of a 0.125-M solution of nitrous acid (a weak acid), with a pH of 2.09.

Solution

The percent ionization for an acid is:

[latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}]_{eq}}{[HNO_{2}]_{0}} \times 100[/latex]

Converting the provided pH to hydronium ion molarity yields

[H3O+] = 10−2.09 = 0.0081 M

Substituting this value and the provided initial acid concentration into the percent ionization equation gives

[latex]\frac{8.1 \times 10^{-3}}{0.125} \times 100 = 6.5%[/latex]

(Recall the provided pH value of 2.09 is logarithmic, and so it contains just two significant digits, limiting the certainty of the computed percent ionization.)

Check Your Learning

Calculate the percent ionization of a 0.10-M solution of acetic acid with a pH of 2.89.

Answer: 1.3% ionized

Link to Learning

View the simulation of strong and weak acids and bases at the molecular level.

Just as for acids, the relative strength of a base is reflected in the magnitude of its base-ionization constant (Kb) in aqueous solutions. In solutions of the same concentration, stronger bases ionize to a greater extent, and so yield higher hydroxide ion concentrations than do weaker bases. A stronger base has a larger ionization constant than does a weaker base. For the reaction of a base, B:

B(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ HB+(aq) + OH−(aq),

the ionization constant is written as

Kb = [latex]\frac{[HN^+][OH^-]}{[b]}[/latex]

Inspection of the data for three weak bases presented below shows the base strength increases in the order NO2 -< CH2CO2 − < NH3.

NO2 −(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ HNO2(aq) + OH−(aq) Kb = 2.17 × 10−11

CH3CO2 −(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ CH3CO2 H(aq) + OH−(aq) Kb = 5.6 × 10−10

NH3(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ NH4 +(aq) + OH−(aq) Kb = 1.8 × 10−5

A table of ionization constants for weak bases appears in Appendix I. As for acids, the relative strength of a base is also reflected in its percent ionization, computed as

% ionization = [OH−]eq /[B]0 ×100%

but will vary depending on the base ionization constant and the initial concentration of the solution.

Relative Strengths of Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs

Brønsted-Lowry acid-base chemistry is the transfer of protons; thus, logic suggests a relation between the relative strengths of conjugate acid-base pairs. The strength of an acid or base is quantified in its ionization constant, Ka or Kb, which represents the extent of the acid or base ionization reaction. For the conjugate acid-base pair HA / A−, ionization equilibrium equations and ionization constant expressions are

HA(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + A−(aq) Ka = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][A^{-}]}{[HA]}[/latex]

A−(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ OH−(aq) + HA(aq) Ka = [latex]\frac{[HA][OH]}{[A^{-}]}[/latex]

Adding these two chemical equations yields the equation for the autoionization for water:

HA(aq) + H2O(l) + A−(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + A−(aq) + OH−(aq) + HA(aq)

2H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + OH−(aq)

As discussed in another chapter on equilibrium, the equilibrium constant for a summed reaction is equal to the mathematical product of the equilibrium constants for the added reactions, and so

Ka x Kb = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][A^{-}]}{[HA]} \times \frac{[HA][OH^{-}]}{[A^{-}]}[/latex] = [H3O+][OH-] = Kw

This equation states the relation between ionization constants for any conjugate acid-base pair, namely, their mathematical product is equal to the ion product of water, Kw. By rearranging this equation, a reciprocal relation between the strengths of a conjugate acid-base pair becomes evident:

Ka = Kw/Kb or Kb = Kw/Ka

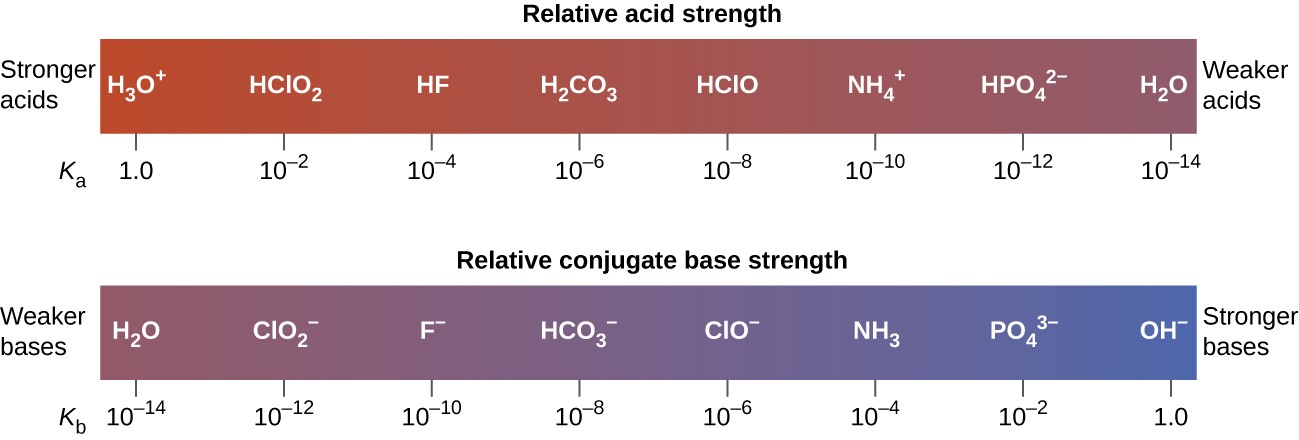

The inverse proportional relation between Ka and Kb means the stronger the acid or base, the weaker its conjugate partner. Figure 14.7 illustrates this relation for several conjugate acid-base pairs.

Figure 14.7 Relative strengths of several conjugate acid-base pairs are shown.

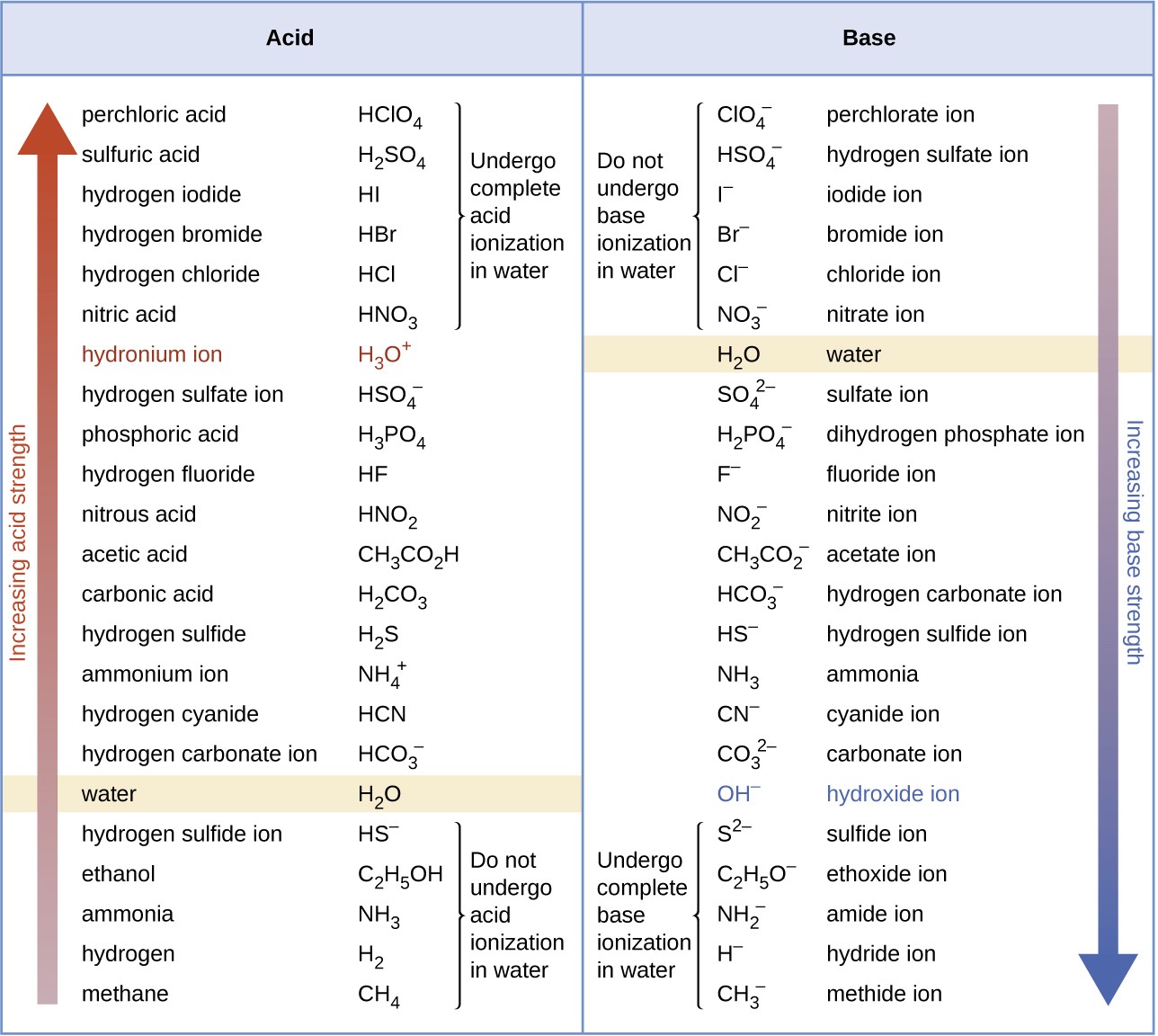

Figure 14.8 This figure shows strengths of conjugate acid-base pairs relative to the strength of water as the reference substance.

The listing of conjugate acid–base pairs shown in Figure 14.8 is arranged to show the relative strength of each species as compared with water, whose entries are highlighted in each of the table’s columns. In the acid column, those species listed below water are weaker acids than water. These species do not undergo acid ionization in water; they are not Bronsted-Lowry acids. All the species listed above water are stronger acids, transferring protons to water to some extent when dissolved in an aqueous solution to generate hydronium ions. Species above water but below hydronium ion are weak acids, undergoing partial acid ionization, wheres those above hydronium ion are strong acids that are completely ionized in aqueous solution.

If all these strong acids are completely ionized in water, why does the column indicate they vary in strength, with nitric acid being the weakest and perchloric acid the strongest? Notice that the sole acid species present in an aqueous solution of any strong acid is H3O+(aq), meaning that hydronium ion is the strongest acid that may exist in water; any stronger acid will react completely with water to generate hydronium ions. This limit on the acid strength of solutes in a solution is called a leveling effect. To measure the differences in acid strength for “strong” acids, the acids must be dissolved in a solvent that is less basic than water. In such solvents, the acids will be “weak,” and so any differences in the extent of their ionization can be determined. For example, the binary hydrogen halides HCl, HBr, and HI are

strong acids in water but weak acids in ethanol (strength increasing HCl < HBr < HI).

The right column of Figure 14.8 lists a number of substances in order of increasing base strength from top to bottom. Following the same logic as for the left column, species listed above water are weaker bases and so they don’t undergo base ionization when dissolved in water. Species listed between water and its conjugate base, hydroxide ion, are weak bases that partially ionize. Species listed below hydroxide ion are strong bases that completely ionize in water to yield hydroxide ions (i.e., they are leveled to hydroxide). A comparison of the acid and base columns in this table supports the reciprocal relation between the strengths of conjugate acid-base pairs. For example, the conjugate bases of the strong acids (top of table) are all of negligible strength. A strong acid exhibits an immeasurably large Ka, and so its conjugate base will exhibit a Kb that is essentially zero:

strong acid :Ka ≈ ∞

conjugate base : Kb = Kw/Ka = Kw /∞ ≈ 0

A similar approach can be used to support the observation that conjugate acids of strong bases (Kb ≈ ∞) are of negligible strength (Ka ≈ 0).

Example 14.8

Calculating Ionization Constants for Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs

Use the Kb for the nitrite ion, NO2−, to calculate the Ka for its conjugate acid.

Solution

Kb for NO2 − is given in this section as 2.17 × 10−11. The conjugate acid of NO2 − is HNO2; Ka for HNO2 can be calculated using the relationship:

Ka × Kb = 1.0 × 10−14 = Kw

Solving for Ka yields

Ka = [latex]\frac{K_{w}}{K_{b}} = \frac{1.0 \times 10^{-14}}{2.17 \times 10^{-11}}[/latex] = 4.6 x 10-4

This answer can be verified by finding the Ka for HNO2 in Appendix H.

Check Your Learning

Determine the relative acid strengths of NH4+ and HCN by comparing their ionization constants. The ionization constant of HCN is given in Appendix H as 4.9 × 10−10. The ionization constant of NH4+ is not listed, but the ionization constant of its conjugate base, NH3, is listed as 1.8 × 10−5.

Answer: NH4+ is the slightly stronger acid (Ka for NH4+ = 5.6 x 10-10)

Acid-Base Equilibrium Calculations

The chapter on chemical equilibria introduced several types of equilibrium calculations and the various mathematical strategies that are helpful in performing them. These strategies are generally useful for equilibrium systems regardless of chemical reaction class, and so they may be effectively applied to acid-base equilibrium problems. This section presents several example exercises involving equilibrium calculations for acid-base systems.

The Ionization of Weak Acids and Weak Bases

Many acids and bases are weak; that is, they do not ionize fully in aqueous solution. A solution of a weak acid in water is a mixture of the nonionized acid, hydronium ion, and the conjugate base of the acid, with the nonionized acid present in the greatest concentration. Thus, a weak acid increases the hydronium ion concentration in an aqueous solution (but not as much as the same amount of a strong acid).

Acetic acid, CH3CO2H, is a weak acid. When we add acetic acid to water, it ionizes to a small extent according to the equation:

giving an equilibrium mixture with most of the acid present in the nonionized (molecular) form. This equilibrium, like other equilibria, is dynamic; acetic acid molecules donate hydrogen ions to water molecules and form hydronium ions and acetate ions at the same rate that hydronium ions donate hydrogen ions to acetate ions to reform acetic acid molecules and water molecules. We can tell by measuring the pH of an aqueous solution of known concentration that only a fraction of the weak acid is ionized at any moment (Figure 4). The remaining weak acid is present in the nonionized form.

For acetic acid, at equilibrium:

Ka = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][CH_{3}CO_{2} ^{-}]}{[CH_{3}CO_{2}H]}[/latex] = 1.8 x 10-5

pH paper indicates that a 0.1-M solution of HCl (beaker on left) has a pH of 1. The acid is fully ionized and [H3O+] = 0.1 M. A 0.1-M solution of CH3CO2H (beaker on right) is a pH of 3 ([H3O+] = 0.001 M) because the weak acid CH3CO2H is only partially ionized. In this solution, [H3O+] < [CH3CO2H]. (credit: modification of work by Sahar Atwa)

| Ionization Reaction | Ka at 25 °C |

|---|---|

| [latex]\text{HSO}_4^{\;\;-}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{SO}_4^{\;\;2-}[/latex] | 1.2 × 10−2 |

| [latex]\text{HF}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{F}^{-}[/latex] | 3.5 × 10−4 |

| [latex]\text{HNO}_2\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{NO}_2^{\;\;-}[/latex] | 4.6 × 10−4 |

| [latex]\text{HCNO}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{NCO}^{-}[/latex] | 2 × 10−4 |

| [latex]\text{HCO}_2\text{H}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{HCO}_2^{\;\;-}[/latex] | 1.8 × 10−4 |

| [latex]\text{CH}_3\text{CO}_2\text{H}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{CH}_3\text{CO}_2^{\;\;-}[/latex] | 1.8 × 10−5 |

| [latex]\text{HCIO}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{CIO}^{-}[/latex] | 2.9 × 10−8 |

| [latex]\text{HBrO}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{BrO}^{-}[/latex] | 2.8 × 10−9 |

| [latex]\text{HCN}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}\;+\;\text{CN}^{-}[/latex] | 4.9 × 10−10 |

| Table 2. Ionization Constants of Some Weak Acids | |

pH paper indicates that a 0.1-M solution of NH3 (left) is weakly basic. The solution has a pOH of 3 ([OH−] = 0.001 M) because the weak base NH3 only partially reacts with water. A 0.1-M solution of NaOH (right) has a pOH of 1 because NaOH is a strong base. (credit: modification of work by Sahar Atwa)

| Ionization Reaction | Kb at 25 °C |

|---|---|

| [latex](\text{CH}_3)_2\text{NH}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;(\text{CH}_3)_2\text{NH}_2^{\;\;+}\;+\;\text{OH}^{-}[/latex] | 5.9 × 10−4 |

| [latex]\text{CH}_3\text{NH}_2\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{CH}_3\text{NH}_3^{\;\;+}\;+\;\text{OH}^{-}[/latex] | 4.4 × 10−4 |

| [latex](\text{CH}_3)_3\text{N}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;(\text{CH}_3)_3\text{NH}^{+}\;+\;\text{OH}^{-}[/latex] | 6.3 × 10−5 |

| [latex]\text{NH}_3\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{NH}_4^{\;\;+}\;+\;\text{OH}^{-}[/latex] | 1.8 × 10−5 |

| [latex]\text{C}_6\text{H}_5\text{NH}_2\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{C}_6\text{N}_5\text{NH}_3^{\;\;+}\;+\;\text{OH}^{-}[/latex] | 4.3 × 10−10 |

| Table 3. Ionization Constants of Some Weak Bases | |

Example 14.9

Determination of Ka from Equilibrium Concentrations

Acetic acid is the principal ingredient in vinegar (Figure 14.9) that provides its sour taste. At equilibrium, a solution contains [CH3CO2H] = 0.0787 M and [H3O+] = [CH3CO2−] = 0.00118 M. What is the value of Ka for acetic acid?

Figure 14.9 Vinegar contains acetic acid, a weak acid. (credit: modification of work by “HomeSpot HQ”/Flickr)

Solution

The relevant equilibrium equation and its equilibrium constant expression are shown below. Substitution of the provided equilibrium concentrations permits a straightforward calculation of the Ka for acetic acid.

CH3CO2H(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + CH3CO2 −(aq)

Ka = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][CH_{3}CO_{2} ^{-}]}{[CH_{3}CO_{2}H]} = \frac{(0.00118)(0.00118)}{0.0787}[/latex] = 1.77 x 10-5

Check Your Learning

The HSO4− ion, weak acid used in some household cleansers:

HSO4 −(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + SO4 2−(aq)

What is the acid ionization constant for this weak acid if an equilibrium mixture has the following composition: [H3O+] = 0.027 M; [HSO4 −] = 0.29 M; and [SO4 2−] = 0.13 M ?

Answer: Ka for HSO4 − = 1.2 × 10−2

Example 14.10

Determination of Kb from Equilibrium Concentrations

Caffeine, C8H10N4O2 is a weak base. What is the value of Kb for caffeine if a solution at equilibrium has [C8H10N4O2] = 0.050 M, [C8H10N4O2H+] = 5.0 × 10−3 M, and [OH−] = 2.5 × 10−3 M?

Solution

The relevant equilibrium equation and its equilibrium constant expression are shown below. Substitution of the provided equilibrium concentrations permits a straightforward calculation of the Kb for caffeine.

C8H10N4O2(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ C8H10N4O2 H+(aq) + OH−(aq)

Kb = [latex]\frac{[C_{8}H_{10}N_{4}O_{2}H^{+}][OH^{-}]}{[C_{8}H_{10}N_{4}O_{2}]} = \frac{(5.0 \times 10^{-3})(2.5 \times 10^{-3})}{0.050}[/latex] = 2.5 x 10-4

Check Your Learning

What is the equilibrium constant for the ionization of the HPO4 2− ion, a weak base

HPO4 2−(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H2PO4 −(aq) + OH−(aq)

if the composition of an equilibrium mixture is as follows: [OH−] = 1.3 × 10−6 M; [H2PO4 −] = 0.042 M; and [HPO42−] = 0.341 M ?

Answer: Kb for HPO4 2− = 1.6 × 10−7

Example 14.11

Determination of Ka or Kb from pH

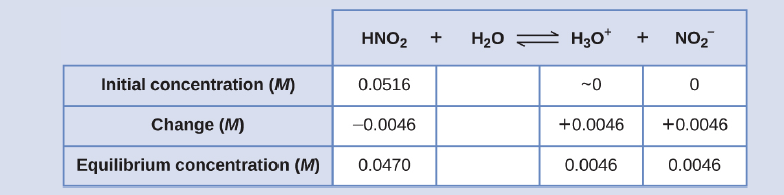

The pH of a 0.0516-M solution of nitrous acid, HNO2, is 2.34. What is its Ka?

HNO2(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + NO2 −(aq)

Solution

The nitrous acid concentration provided is a formal concentration, one that does not account for any chemical equilibria that may be established in solution. Such concentrations are treated as “initial” values for equilibrium calculations using the ICE table approach. Notice the initial value of hydronium ion is listed as approximately zero because a small concentration of H3O+ is present (1 × 10−7 M) due to the autoprotolysis of water. In many cases, such as all the ones presented in this chapter, this concentration is much less than that generated by ionization of the acid (or base) in question and may be neglected.

The pH provided is a logarithmic measure of the hydronium ion concentration resulting from the acid ionization of the nitrous acid, and so it represents an “equilibrium” value for the ICE table:

[H3 O+ ] = 10−2.34 = 0.0046 M

The ICE table for this system is then

Finally, calculate the value of the equilibrium constant using the data in the table:

Ka = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][NO_{2} ^{-}]}{[HNO_{2}]} = \frac{(0.0046)(0.0046)}{(0.0470)}[/latex] = 4.6 x 10-4

Check Your Learning.

The pH of a solution of household ammonia, a 0.950-M solution of NH3, is 11.612. What is Kb for NH3.

Answer: Kb = 1.8 × 10−5

Example 14.12

Calculating Equilibrium Concentrations in a Weak Acid Solution

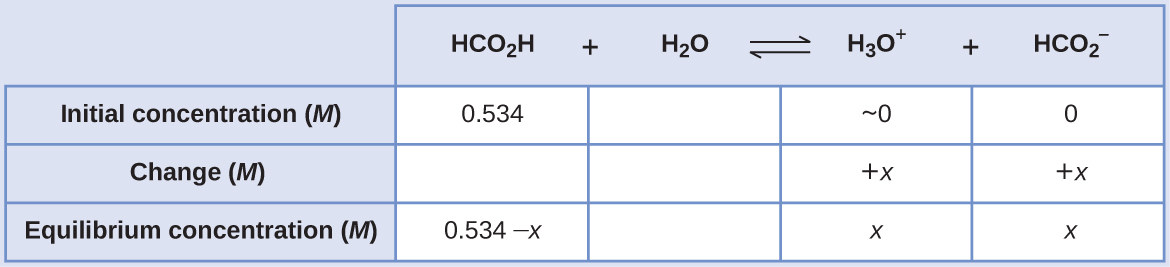

Formic acid, HCO2H, is one irritant that causes the body’s reaction to some ant bites and stings (Figure 14.10).

Figure 14.10 The pain of some ant bites and stings is caused by formic acid. (credit: John Tann)

What is the concentration of hydronium ion and the pH of a 0.534-M solution of formic acid?

HCO2 H(aq) + H2 O(l) ⇌ H3 O+(aq) + HCO2 −(aq) Ka = 1.8 × 10−4

Solution

The ICE table for this system is

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Ka expression gives

Ka = 1.8 x 10-4 = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][HCO_{2} ^{-}]}{[HCO_{2}H]}[/latex]

= [latex]\frac{(x)(x)}{0.534 - x}[/latex] = 1.8 x 10-4

The relatively large initial concentration and small equilibrium constant permits the simplifying assumption that x will be much lesser than 0.534, and so the equation becomes

Ka = 1.8 x 10-4 = [latex]\frac{x^{2}}{0.534}[/latex]

Solving the equation for x yields

x2 = 0.534 x (1.8 x 10-4) = 9.6 x 10-5

x = [latex]\sqrt{9.6 \times 10^{-5}}[/latex]

= 9.8 x 10-3 M

To check the assumption that x is small compared to 0.534, its relative magnitude can be estimated:

[latex]\frac{x}{0.534} = \frac{9.8 \times 10^{-3}}{0.534}[/latex] = 1.8 x 10-2 (1.8% of 0.534)

Because x is less than 5% of the initial concentration, the assumption is valid.

As defined in the ICE table, x is equal to the equilibrium concentration of hydronium ion:

x = [H3O+] = 0.0098 M

Finally, the pH is calculated to be

pH = −log[H3O+ ] = −log(0.0098) = 2.01

Check Your Learning

Only a small fraction of a weak acid ionizes in aqueous solution. What is the percent ionization of a 0.100-M solution of acetic acid, CH3CO2H?

CH3CO2 H(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + CH3CO2 −(aq) Ka = 1.8 × 10−5

Answer: percent ionization = 1.3%

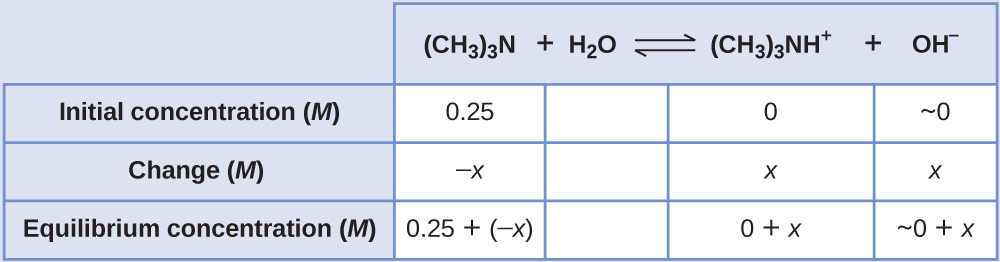

Example 14.13

Calculating Equilibrium Concentrations in a Weak Base Solution

Find the concentration of hydroxide ion, the pOH, and the pH of a 0.25-M solution of trimethylamine, a weak base:

(CH3)3N(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ (CH3)3 NH+(aq) + OH−(aq) Kb = 6.3 × 10−5

Solution

The ICE table for this system is

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Kb expression gives

Kb = [latex]\frac{[(CH_{3})_{3} NH^{+}][OH^{-}]}{[(CH_{3})_{3}N]} = \frac{(x)(x)}{0.25 - x}[/latex] = 6.3 x 10-5

Assuming x << 0.25 and solving for x yields

x = 4.0 × 10−3 M

This value is less than 5% of the initial concentration (0.25), so the assumption is justified. As defined in the ICE table, x is equal to the equilibrium concentration of hydroxide ion:

[OH−] = ~ 0 + x = x = 4.0 × 10−3 M

= 4.0 × 10−3 M

The pOH is calculated to be

pOH = -log(4.0 x 10-3) = 2.40

Using the relation introduced in the previous section of this chapter:

pH + pOH = pKw = 14.00

permits the computation of pH:

pH = 14.00 − pOH = 14.00 − 2.40 = 11.60

Check Your Learning

Calculate the hydroxide ion concentration and the percent ionization of a 0.0325-M solution of ammonia, a weak base with a Kb of 1.76 × 10−5.

Answer: 7.56 × 10−4 M, 2.33%

In some cases, the strength of the weak acid or base and its formal (initial) concentration result in an appreciable ionization. Though the ICE strategy remains effective for these systems, the algebra is a bit more involved because the simplifying assumption that x is negligible can not be made. Calculations of this sort are demonstrated in Example 14.14 below.

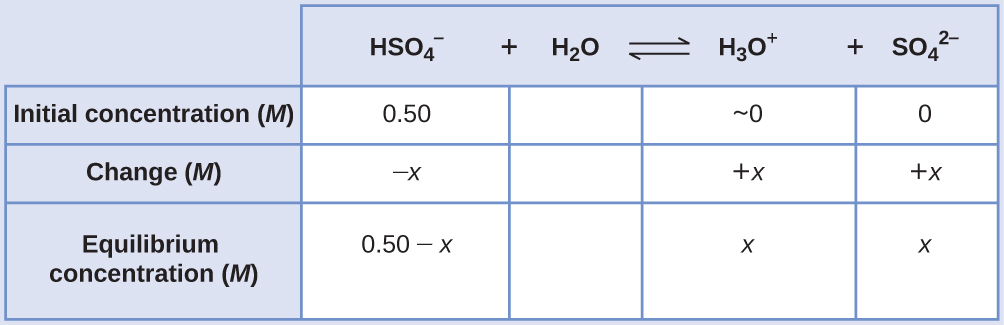

Example 14.14

Calculating Equilibrium Concentrations without Simplifying Assumptions

Sodium bisulfate, NaHSO4, is used in some household cleansers as a source of the HSO4 − ion, a weak acid. What is the pH of a 0.50-M solution of HSO4 − ?

HSO4 −(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ H3O+(aq) + SO4 2−(aq) Kb = 1.2 × 10−2

Solution

The ICE table for this system is

Substituting the equilibrium concentration terms into the Ka expression gives

Ka = 1.2 x 10-2 = [latex]\frac{[H_{3}O^{+}][SO_{4} ^{2-}]}{[HSO_{4} ^{-}]} = \frac{(x)(x)}{0.50 - x}[/latex]

If the assumption that x << 0.5 is made, simplifying and solving the above equation yields

x = 0.077 M

This value of x is clearly not significantly less than 0.50 M; rather, it is approximately 15% of the initial concentration:

When we check the assumption, we calculate:

[latex]\frac{x}{[HSO_{4} ^{-}]_{i}}[/latex]

[latex]\frac{x}{0.50} = \frac{7.7 \times 10^{-2}}{0.50}[/latex] = 0.15 (15%)

Because the simplifying assumption is not valid for this system, the equilibrium constant expression is solved as follows:

Ka = 1.2 × 10−2 = [latex]\frac{(x)(x)}{0.50 - x}[/latex]

Rearranging this equation yields

6.0 × 10−3 − 1.2 × 10−2 x = x2

Writing the equation in quadratic form gives

x2 + 1.2 × 10−2 x − 6.0 × 10−3 = 0

Solving for the two roots of this quadratic equation results in a negative value that may be discarded as physically irrelevant and a positive value equal to x. As defined in the ICE table, x is equal to the hydronium concentration.

x = [H3 O+] = 0.072 M

pH = − log[H3 O+ ] = − log(0.072) = 1.14

Check Your Learning

Calculate the pH in a 0.010-M solution of caffeine, a weak base:

C8H10N4O2(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ C8H10N4O2H+(aq) + OH−(aq) Kb = 2.5 × 10−4

Answer: pH 11.16

Effect of Molecular Structure on Acid-Base Strength

Binary Acids and Bases

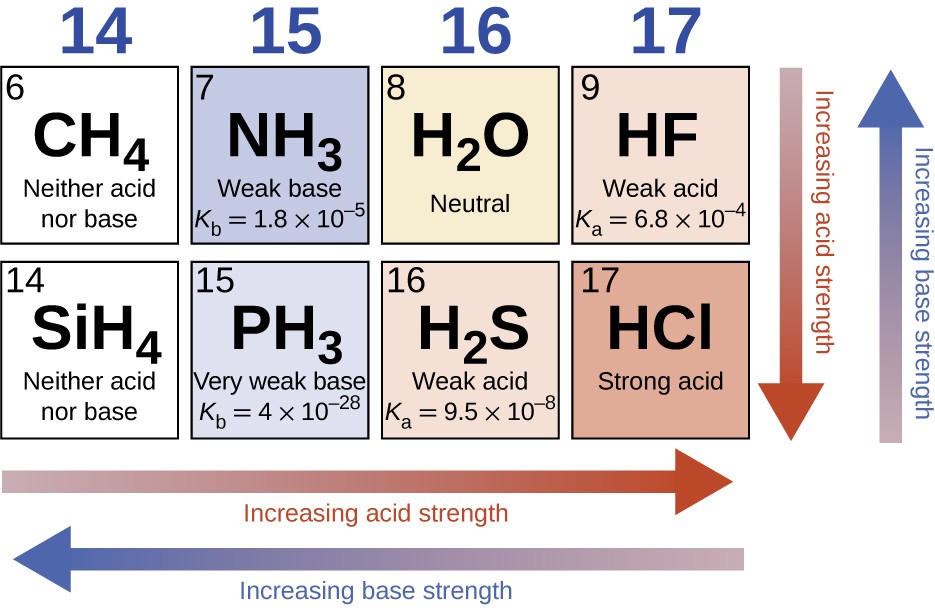

In the absence of any leveling effect, the acid strength of binary compounds of hydrogen with nonmetals (A) increases as the H-A bond strength decreases down a group in the periodic table. For group 17, the order of increasing acidity is HF < HCl < HBr < HI. Likewise, for group 16, the order of increasing acid strength is H2O < H2S < H2Se < H2Te.

Across a row in the periodic table, the acid strength of binary hydrogen compounds increases with increasing electronegativity of the nonmetal atom because the polarity of the H-A bond increases. Thus, the order of increasing acidity (for removal of one proton) across the second row is CH4 < NH3 < H2O < HF; across the third row, it is SiH4 < PH3 < H2S < HCl (see Figure 14.11).

Figure 14.11 The figure shows trends in the strengths of binary acids and bases.

Ternary Acids and Bases

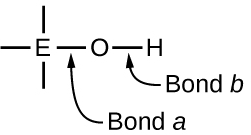

Ternary compounds composed of hydrogen, oxygen, and some third element (“E”) may be structured as depicted in the image below. In these compounds, the central E atom is bonded to one or more O atoms, and at least one of the O atoms is also bonded to an H atom, corresponding to the general molecular formula OmE(OH)n. These compounds may be acidic, basic, or amphoteric depending on the properties of the central E atom. Examples of such compounds include sulfuric acid, O2S(OH)2, sulfurous acid, OS(OH)2, nitric acid, O2NOH, perchloric acid, O3ClOH, aluminum hydroxide, Al(OH)3, calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2, and potassium hydroxide, KOH:

If the central atom, E, has a low electronegativity, its attraction for electrons is low. Little tendency exists for the central atom to form a strong covalent bond with the oxygen atom, and bond a between the element and oxygen is more readily broken than bond b between oxygen and hydrogen. Hence bond a is ionic, hydroxide ions are released to the solution, and the material behaves as a base—this is the case with Ca(OH)2 and KOH. Lower electronegativity is characteristic of the more metallic elements; hence, the metallic elements form ionic hydroxides that are by definition basic compounds.

If, on the other hand, the atom E has a relatively high electronegativity, it strongly attracts the electrons it shares with the oxygen atom, making bond a relatively strongly covalent. The oxygen-hydrogen bond, bond b, is thereby weakened because electrons are displaced toward E. Bond b is polar and readily releases hydrogen ions to the solution, so the material behaves as an acid. High electronegativities are characteristic of the more nonmetallic elements. Thus, nonmetallic elements form covalent compounds containing acidic −OH groups that are called oxyacids.

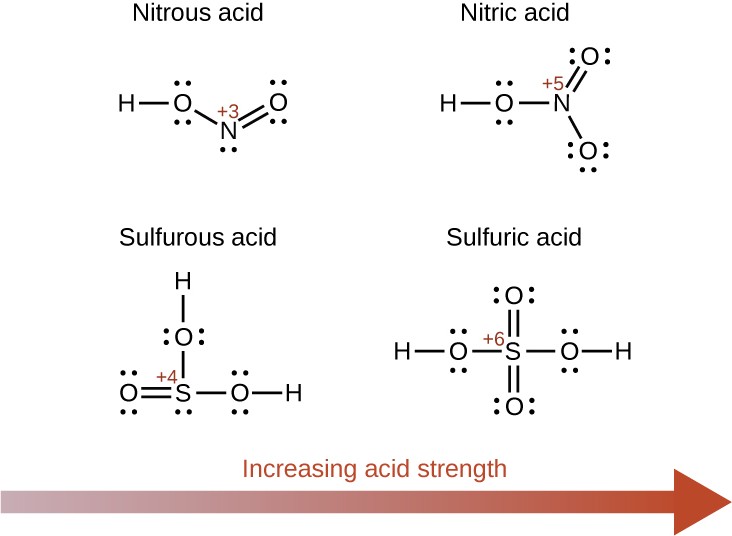

Increasing the oxidation number of the central atom E also increases the acidity of an oxyacid because this increases the attraction of E for the electrons it shares with oxygen and thereby weakens the O-H bond. Sulfuric acid, H2SO4, or O2S(OH)2 (with a sulfur oxidation number of +6), is more acidic than sulfurous acid, H2SO3, or OS(OH)2 (with a sulfur oxidation number of +4). Likewise nitric acid, HNO3, or O2NOH (N oxidation number = +5), is more acidic than nitrous acid, HNO2, or ONOH (N oxidation number = +3). In each of these pairs, the oxidation number of the central atom is larger for the stronger acid (Figure 14.12).

Figure 14.12 As the oxidation number of the central atom E increases, the acidity also increases.

Hydroxy compounds of elements with intermediate electronegativities and relatively high oxidation numbers (for example, elements near the diagonal line separating the metals from the nonmetals in the periodic table) are usually amphoteric. This means that the hydroxy compounds act as acids when they react with strong bases and as bases when they react with strong acids. The amphoterism of aluminum hydroxide, which commonly exists as the hydrate Al(H2O)3(OH)3, is reflected in its solubility in both strong acids and strong bases. In strong bases, the relatively insoluble hydrated aluminum hydroxide, Al(H2O)3(OH)3, is converted into the soluble ion, [Al(H2O)2(OH)4]−, by reaction with hydroxide ion:

Al(H2O)3(OH)3(aq) + OH−(aq) ⇌ H2 O(l) + [Al(H2O)2(OH)4]−(aq)

In this reaction, a proton is transferred from one of the aluminum-bound H2O molecules to a hydroxide ion in solution. The Al(H2O)3(OH)3 compound thus acts as an acid under these conditions. On the other hand, when dissolved in strong acids, it is converted to the soluble ion [Al(H2O)6]3+ by reaction with hydronium ion:

3H3O+(aq) + Al(H2O)3(OH)3(aq) ⇌ Al(H2O)6 3+(aq) + 3H2O(l)

In this case, protons are transferred from hydronium ions in solution to Al(H2O)3(OH)3, and the compound functions as a base.

Key Concepts and Summary

The strengths of Brønsted-Lowry acids and bases in aqueous solutions can be determined by their acid or base ionization constants. Stronger acids form weaker conjugate bases, and weaker acids form stronger conjugate bases. Thus strong acids are completely ionized in aqueous solution because their conjugate bases are weaker bases than water. Weak acids are only partially ionized because their conjugate bases are strong enough to compete successfully with water for possession of protons. Strong bases react with water to quantitatively form hydroxide ions. Weak bases give only small amounts of hydroxide ion. The strengths of the binary acids increase from left to right across a period of the periodic table (CH4 < NH3 < H2O < HF), and they increase down a group (HF < HCl < HBr < HI). The strengths of oxyacids that contain the same central element increase as the oxidation number of the element increases (H2SO3 < H2SO4). The strengths of oxyacids also increase as the electronegativity of the central element increases [H2SeO4 < H2SO4].

Key Equations

- [latex]K_{\text{a}} = \frac{[\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}][\text{A}^{-}]}{[\text{HA}]}[/latex]

- [latex]K_{\text{b}} = \frac{[\text{HB}^{+}][\text{OH}^{-}]}{[\text{B}]}[/latex]

- [latex]K_{\text{a}}\;\times\;K_{\text{b}} = 1.0\;\times\;10^{-14} = K_{\text{w}}[/latex]

- [latex]\text{Percent ionization} = \frac{[\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+}]_{\text{eq}}}{[\text{HA}]_{0}}\;\times\;100[/latex]