Chapter 13.1 – Introduction to the Agriculture Economics

The Agricultural Market Landscape

The agricultural market landscape is the economic system that produces, distributes, and consumes agricultural products and services.

Learning Objectives

Outline the evolution of the agriculture market over time

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The history of agriculture is complex, spanning back thousands of years across a wide variety of different geographic regions, climates, cultures, and technological approaches.

- The roots of agriculture are derived over 10,000 years ago, with tribes executing forest gardening alongside the domestication of animals in the Fertile Crescent region.

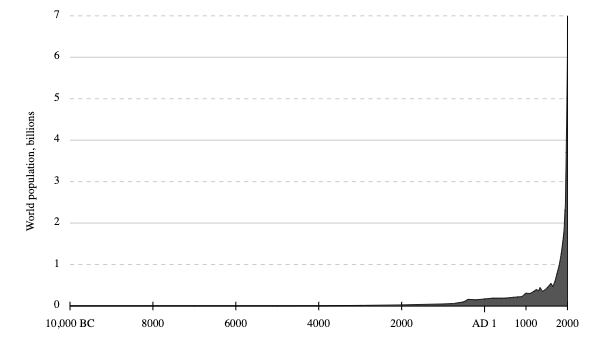

- As population expanded dramatically over time (see, so did the efficiency of agriculture economics. This began with agricultural improvements such as the hoe and is represented today with genetic engineering, robotics, irrigation, etc.

- This rapid expansion coupled with the essential role of food in our society has generated a field of economics solely dedicated to observing and predicting trends within the agriculture market landscape.

- Interesting trends in the agricultural market pertain to the decrease in cost for the actual farming aspects and an increase in costs for the distribution and sales system (particularly in the U.S.). This is largely a result of technological progress.

Key Terms

- Agricultural Economics: The study of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services related to food.

Agriculture, in many ways, has been the fundamental economic industry throughout history. The production and exchange of food laid the groundwork for all bartering, making it likely to be the oldest market in history. The production of food in modern times in developed nations is oddly taken for granted, as surpluses tend to define the market in pursuit of providing options. Developing nations view agriculture quite differently, where famines and low yield years can dramatically affect the overall food supply in a given region. Due to the critical importance of food production, the agricultural market landscape is one of the most studied and evolved economic segments.

The History of Agriculture

The history of agriculture is complex, spanning back thousands of years across a wide variety of different geographic regions, climates, cultures, and technological approaches. Over 10,000 years ago, tribes began executing forest gardening. This evolved in the Fertile Crescent region into the domestication of animals (i.e. cattle, sheep, goats, pigs), growing of wheat and barley in Jordan Valley and the growth of cereal in Syria (all still about 10,000 years ago).

As population expanded dramatically over time (see ), so did the efficiency of agriculture economics. This began with agricultural improvements such as the hoe and the plow (2500 B.C.), irrigation via canals, and biological pest control as early as the bronze and iron ages. This evolved further in the middle ages with the advent of fertilizers, three field techniques, draft horses, and improved international exchange. Indeed, until the Industrial Revolution (18th and 19th centuries) the vast majority of the human population labored long hard days to generate enough food to feed the masses.

The modern era of farming is increasingly defined by selective breeding, crop rotation, economies of scale, electronic machinery, genetic modification, pesticides, and a host of other solutions that have rapidly expanded the overall potential capacity in farming.

Agricultural Economics

This rapid expansion coupled with the essential role of food in our society has generated a field of economics solely dedicated to observing and predicting trends within the agriculture market landscape. Basic macro and micro-economic principles apply to farming, as do the existence of externalities such as climate change and nutritional health. Agricultural economics is defined as the economic system that produces, distributes, and consumes agricultural products and services. This represents a large interconnected supply chain on a global scale.

Interesting trends in the agricultural market pertain to the decrease in cost for the actual farming aspects and an increase in costs for the distribution and sales system (particularly in the U.S.). This is largely a result of technological progress greatly reducing the need for human labor in the production of agricultural goods, weighting the costs more heavily on the human resources side of the equation.

The politics and economics of agriculture are also relevant issues on a global scale. US agricultural subsidies have had a large impact on international trade flows. The subsidies make US agricultural products artificially cheap, too cheap for developing nations to compete with. Developing nations, which may rely more heavily on agriculture in their economy than developed nations, argue that the US should reduce its agriculture subsidies. This tension is perhaps the biggest cause of the failure of the Doha Round, a World Trade Organization push for more open global trade, to make any progress since its initiation in 2001.

Subsidies and Income Supports

An agricultural subsidy is a government grant paid to incumbents in the industry to reduce costs and influence the supply of commodities.

Learning Objectives

Analyze the positive and negative affects of subsidies on agricultural economics.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

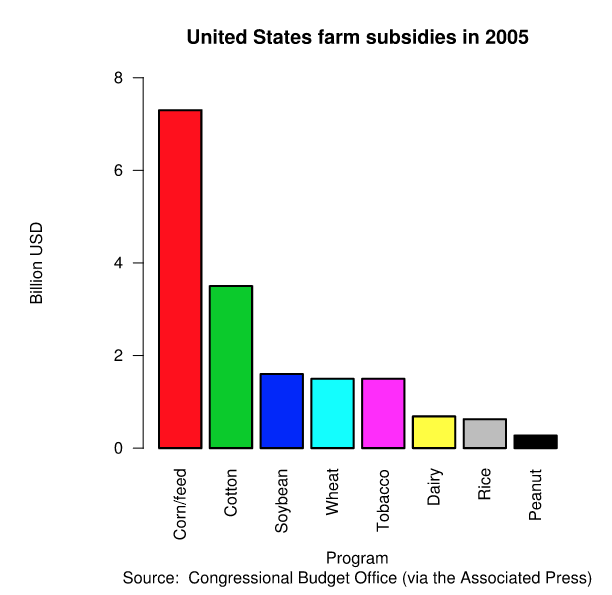

- Subsidized goods generally include wheat, corn, barley, oats, sorghum, milk, rice, peanuts, tobacco, soybean, cotton, lamb, beef, chicken and pork.

- Another, less direct, form of subsidy is in the taxing system for consumers. Consumers are not charged tax on food goods and clothes, which are considered necessities and thus should be provided at the lowest costs possible.

- In the context of international trade, government assistance in industry provides an unfair competitive advantage for those companies receiving the support.

- Overall, while subsidies are largely a good thing and enable individuals to buy the necessities, there are clear cut downsides to subsidies as well.

- Overall, while subsidies are largely a good thing and enable individuals to buy the necessities, there are clear cut downsides to subsidies as well. Politics must find a way to mitigate the negative externalities.

Key Terms

- subsidy: Government assistance to a business or economic sector.

- externalities: Impacts, positive or negative, on any party not involved in a given economic transaction or act.

When governments want to ensure their citizens have access to healthy foods at reasonable prices, a variety of governmental supports are provided to the industry to ensure it maintains low costs of production and high output. This is generally in the form of subsidy and income supports, which alleviate some competitive dynamics and operating expenses to maintain reasonable price points in the market economically.

Subsidies

An agricultural subsidy is defined as a government grant paid to farmers to supplement income and influence the overall cost and supply of certain commodities. In this industry, subsidized goods generally include wheat, corn, barley, oats, sorghum, milk, rice, peanuts, tobacco, soybean, cotton, lamb, beef, chicken and pork. illustrates the governmental priorities, based upon subsidies provided, for specific agricultural goods in the United States. These subsidies play a large role in enabling higher supply at lower price points, supporting the domestic agricultural industry.

Another, less direct, form of subsidy is in the taxing system for consumers. Consumers are not charged tax on food goods and clothes, which are considered necessities and thus should be provided at the lowest costs possible. These consumer-based subsidies are another governmental attempt to enable citizens in the country to purchase basic food stuffs required to survive. Food stamps are a similar concept, used to empower low income individuals and ensure they have access to these basic foods as well (food stamps are often limited to milk, eggs, bread and other core foods).

Impacts of Subsidies

While these subsidies above are designed to have a positive effect on consumers looking to purchase foods, there are externalities to this process that can have a damaging effect on other groups:

- Global Effects: While domestic subsidies are good for driving up production domestically, it suppresses competition in the context of international trade. Government assistance in an industry is argued to provide an unfair competitive advantage for those companies, artificially lowering their costs of production, sometimes below the feasible level for countries (especially developing nations) not receiving these supports.

- Developing Nations: A complement to the above discussion is the effect on poverty and developing nations without the infrastructure to provide subsidies for their own farmers. The International Food Policy Research Institute has estimated a total loss of economic growth in developing nations at $24 billion in 2003, all of which translates to lost income for individuals who desperately need it.

- Nutrition: Another interesting side effect of subsidies and the artificially reduced price of food is obesity and overeating. Some argue that these low prices provide the incentive to buy more food than is necessary, and this overconsumption has resulted in a highly unhealthy culture (particularly in the U.S.).

- Environmental Implications: As food prices reduce distribution increases, thus driving an environmental externality which already existed even further. The cost, environmentally, of transporting a high quantity of agricultural goods across the globe has resulted in high degrees of pollution and waste.

Overall, while subsidies are largely a good thing and enable individuals to buy the necessities, there are clear cut downsides to subsidies as well. Politics must find a way to mitigate the negative consequences while increasing the positive effects, allowing for balanced and healthy consumption across all demographics.

Price Supports

Price supports are subsidies or price controls used by the government to artificially increase or decrease prices in the agriculture market.

Learning Objectives

Assess the way in which price controls affect supply, demand, and equilibrium pricing in agricultural economics.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Governments enact a variety of price controls on the agriculture business, both in the U.S. and abroad, to ensure desired supply and prices for specific necessities.

- Price supports are defined as subsidies or price controls that are leveraged by the government to artificially increase or decrease prices, and alter the supply consumed/quantity demanded by individuals within the system.

- The government may artificially increase prices by purchasing a portion of the consumer surplus or artificially increase quantity by offering subsidies to producers. This allows government control over the established equilibrium in agriculture.

- The United States currently pays out around $20 billion annually to farmers and producers in agriculture in the form of subsidies via farm bills in order to artificially reduce prices and shift the supply curve.

- The subsidies provide a price floor (or a minimum price in which farmers can be reimbursed for certain products). This is a significant economic policy of price control to ensure farmers have proper incentives and revenues to continue to produce.

Key Terms

- Price support: A subsidy or a price control with the intended effect of keeping the market price of a good higher or the quantity consumer higher within a market.

- Subsidies: Financial support or assistance, such as a grant.

The agriculture industry is a critical component of any national economy because it represents both a substantial portion of gross domestic product and it is a core necessity for citizens within the system. Due to the fact that these goods are necessities, it is also important to keep in mind the way in which supply and demand would operate if there was a limited supply (required for survival, and thus potential demand upsides could be boundless). Due to these factors, governments enact a variety of price controls on the agriculture business, both in the U.S. and abroad.

Defining Price Supports

Price supports are defined as subsidies or price controls that are leveraged by the government to artificially increase or decrease prices, and thus alter the supply consumed/quantity demanded by individuals within the system. Understanding the effects of subsidies and price controls is critical in industries with a high degree of government involvement, and agriculture is one of the most affected industries.

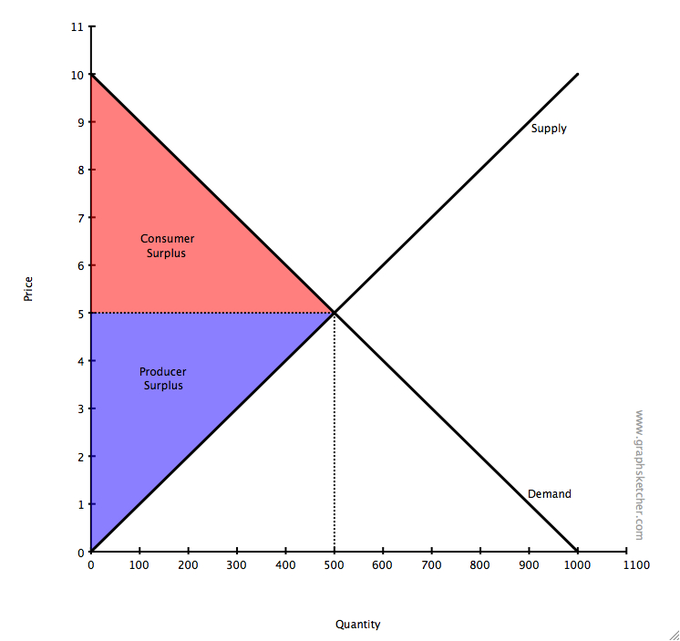

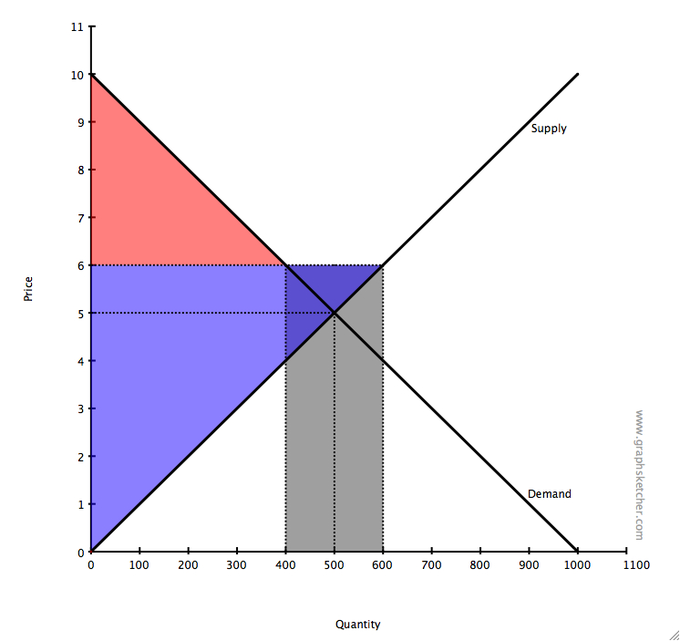

Figure 13.3 is simply a supply and demand curve that demonstrates the consumer surplus and producer surplus opportunities in basic supply and demand chart. In this scenario, without external governmental intervention, the price equilibrium will remain in the center of the graph. However, the government may implement price supports that artificially consume some of the consumer surplus (in, this is 200 units). This drives the price upwards to $6 per unit despite the fact that the consumer is not gaining additional quantity (it is artificial quantity, as purchased by the government).

Applying Price Supports to Agricultural Economics

The United States currently pays out around $20 billion annually to farmers and producers in agriculture in the form of subsidies via farm bills in order to artificially reduce prices and shift the supply curve outward to ensure the overall supply in the market is high enough to satisfy all prospective consumers. It is important to note how dramatically the recipients of farming subsidies have changed over time in the United States. In 1925, there were around 6,000,000 small farms of which 25% of the nation resided. By 1997, 72% of farm sales come from 157,000 large farms and only 2% of the U.S. population resides there. This is an interesting economic factor in farm subsidies, as these subsidies are largely going to corporations of substantial size, as opposed to small farmers.

The subsidies provide a price floor (or a minimum price in which farmers can be reimbursed for certain products). This is a significant economic policy of price control to ensure farmers have proper incentives and revenues to continue to produce at the level of goods desired by the U.S. government. Agricultural economics is a highly complicated market as a result of these price supports and controls, particularly from the perspective of subsidization and price control.

Supply Reduction

Agricultural aggregate supply can be reduced through external capacity potential or governmental interventions.

Learning Objectives

Identify factors resulting in global reductions in agricultural supply levels.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Government policy has a large impact on the agriculture market, usually in the form of subsidies and price ceilings, by controlling the overall supply and demand equilibrium points in the market.

- Governments may reduce supply through utilizing quotas (limiting imports ) or providing foreign aid (actively reducing domestic demand).

- Environmental concerns have also been widely cited as a reductive influence on the agriculture market. Global warming (increased average temperatures) has demonstrated a negative effect on overall plant yield for certain products.

- Other concerns reducing supply revolve around dramatic soil damage due to short-term yield increasing strategies, growing immunity to pesticides, loss of rural space for farming (due to urbanization), and availability of clean water for irrigation.

Key Terms

- Dumping: Selling goods at less than their normal price, especially in the export market as a means of securing a monopoly.

- Quotas: A restriction on the import of a good to a specific quantity.

Agricultural economics is largely bound by concepts of climate and overall world food producing capacity (i.e. farmlands and infrastructure), while simultaneously being enabled by government policy, technological advances, and the continued growth of developing nations. Understanding the reductions in aggregate supply in this industry, as a result of government policy or economic limits, is a critical component in understanding agricultural economics. We will look at both the governmental components and the climatic/aggregate demand components contributing to overall supply in this industry.

Governmental Policy

Government policy has a large impact on the agriculture market. Both subsidies and price ceilings are common and affect the overall supply and demand equilibrium points in the market. Governmental policy to reduce supply also exists and is executed often from a global trade perspective. One of the largest risks in this industry, due to the high degree of subsidization, is ‘ dumping. ‘ Dumping is the process of selling undervalued goods in another market, upsetting price points and equilibrium. In this scenario, government policies may set quotas, or import limits, to reduce supply.

A second reduction in supply that is quite common in developed nations is utilizing surplus for foreign aid. Many developing nations lack the requisites to generate the appropriate supply of agriculture to feed the population. In this scenario, the leveraging of the surplus in one country can benefit the other country via aid, and in turn correct the supply/demand equilibrium in the donating country to the desired level.

Climate Change

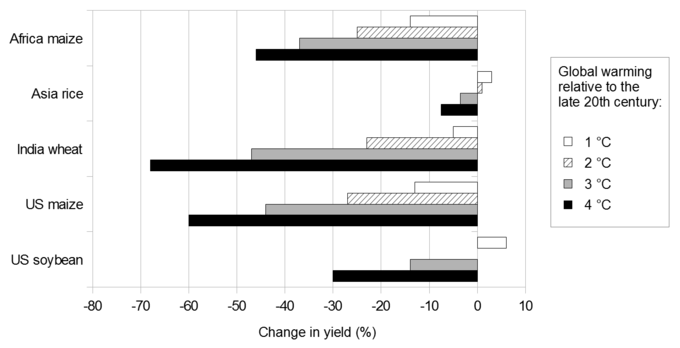

Environmental concerns have also been widely cited as a reductive influence on the agriculture market. Global warming has been slowly increasing temperatures as the ozone layer erodes due to a variety of pollutants, altering the ecosystem averages outside of the evolutionary environment in which many agricultural products historically grew. Climate changes mean a different growing environment for plants, which are not used to it. illustrates the reduction in yield as a result of altering climatic environments. Shifts in climate drastically reduce aggregate supply.

Each set contains 4 bars that represent global warming relative to the late twentieth century: 1 degree Celsius, 2 degrees, 3 degrees and 4 degrees.

Approximate bar values:

Africa maize: 1 degree: -15%; 2 degrees: -25%; 3 degrees: -37%; 4 degrees: -47%

Asia rice: 1 degree: 3%; 2 degrees: 1%; 3 degrees: -4%; 4 degrees: -8%

India wheat: 1 degree: -5%; 2 degrees: -23%; 3 degrees: -47%; 4 degrees: -68%

U.S. maize: 1 degree: 5%; 2 degrees: 0%; 3 degrees: -14%; 4 degrees: -30%

Evaluating Policies

Agriculture requires a vast support system and a great deal of oversight, addressing industry threats and utilizing policy-based tools.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the economics of agriculture policies.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The political frame of the agriculture market is complex, with a wide range of critical concerns that need to be addressed both domestically and internationally.

- Concerns to keep in mind revolve around the international markets, bio-security, infrastructure, technology, water, and resource allocation to enable effective agricultural markets.

- Governments can use import quotas, subsidies, price floors, price ceilings, and aid to control their domestic market supply, demand, and equilibrium price point.

- Combining the issues above with tools provided, the agricultural business can change dramatically as a result of the concerns and activities of the respective government in a given economy.

Key Terms

- infrastructure: The basic facilities, services, and installations needed for the functioning of a community or society.

- Biosecurity: The protection of plants and animals against harm from disease or from human exploitation.

The political frame of the agriculture market is hugely complex, with a wide range of critical concerns that need to be addressed both domestically and internationally. Agricultural policy differs from nation to nation, but has a number of key questions and considerations that occur across the board. The purpose of this atom is to outline the various trends in agricultural economic policy, and how these governmental policies can be evaluated for efficacy in their respective markets.

Policy Concerns

Agriculture requires a vast support system and a great deal of oversight, as the consumption of grown foods poses a huge safety threat alongside a critical need for the health and survival of a civilization. Below is a list of core questions to keep in mind when evaluating agricultural policy:

- Biosecurity: The ability of a country to consistently provide enough food for its citizens is a major concern. Pests and diseases are a significant threat to yield rates and must be closely observed and regulated.

- International Trading Environment: Global agricultural trade is a complex issue, with quality control, pricing (dumping), and import/export tariffs. The dangers of biosecurity, or lack thereof, in particular, are quite stringent.

- Infrastructure: Transporting goods, irrigation facilities, land utilization, and a variety of other logistics concerns are required by the government to enable effective economic trade (domestically and internationally).

- Technology: This is a critical driving force in increasing yield and lowering costs in the agriculture business. Enabling technological progress is a critical investment and something governments must provide incentives for.

- Water: Access to clean, potable water is a basic necessity to which not everyone has access. Effective sewage systems for irrigation and effective water treatment for sanitation are a required input and must be provided via governmental centralized infrastructure.

- Resource Access: Ensuring access to land and biodiversity is another important component of a successful agricultural industry. Protection of environmental land and the overall ecosystem is an important policy consideration.

Policy Tools

With the above concerns in mind, it is also useful to understand some of the tools leveraged by governments to enable this industry:

- Subsidies: The government can utilize subsidies to reduce price points and increase the overall supply within a system. The use of subsidies in developed nations has been a major point of international contention, since they may force developing nations out of the global agriculture market.

- Price Floors/Ceilings: Price floors provide a minimum price point for a given product while price ceilings create a maximum price point. These are used to ensure appropriate pricing in a given industry (see ), and are often used in agriculture to control price points.

- Import Quotas: Policymakers often implement quotas in agriculture to retain more control over prices and protect domestic incumbents. Quotas, like other forms of trade protection, benefit the local industry.

- Aid: When aggregate supply is too high in a home country or there is a crisis in another, governments can provide their surplus to nations in need of food. This is both a way to provide utilitarian value while reducing aggregate supply.

Combining the issues above with tools provided, the agricultural business can change dramatically as a result of the concerns and activities of the respective government in a given economy. This is useful in controlling food prices, reducing waste, enabling efficiency and avoiding biosecurity issues.