8.3 – Cellular Respiration

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast the electron transport system location and function in a prokaryotic cell and a eukaryotic cell

- Compare and contrast the differences between substrate-level and oxidative phosphorylation

- Explain the relationship between chemiosmosis and proton motive force

- Describe the function and location of ATP synthase in a prokaryotic versus eukaryotic cell

- Compare and contrast aerobic and anaerobic respiration

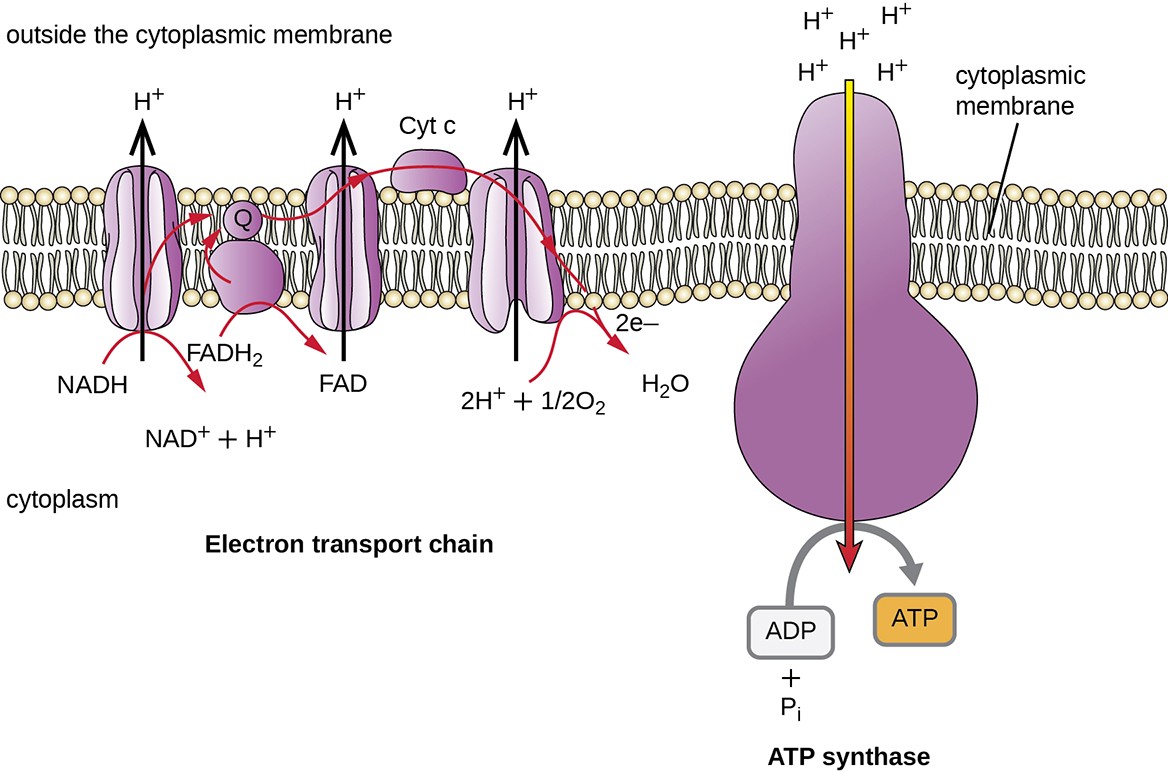

We have just discussed two pathways in glucose catabolism—glycolysis and the Krebs cycle—that generate ATP by substrate-level phosphorylation. Most ATP, however, is generated during a separate process called oxidative phosphorylation, which occurs during cellular respiration. Cellular respiration begins when electrons are transferred from NADH and FADH2—made in glycolysis, the transition reaction, and the Krebs cycle—through a series of chemical reactions to a final inorganic electron acceptor (either oxygen in aerobic respiration or non-oxygen inorganic molecules in anaerobic respiration). These electron transfers take place on the inner part of the cell membrane of prokaryotic cells or in specialized protein complexes in the inner membrane of the mitochondria of eukaryotic cells. The energy of the electrons is harvested to generate an electrochemical gradient across the membrane, which is used to make ATP by oxidative phosphorylation.

Electron Transport System

The electron transport system (E.T.S) is the last component involved in the process of cellular respiration; it comprises a series of membrane-associated protein complexes and associated mobile accessory electron carriers (Figure 8.15). Electron transport is a series of chemical reactions that resembles a bucket brigade in that electrons from NADH and FADH2 are passed rapidly from one ETS electron carrier to the next. These carriers can pass electrons along in the ETS because of their redox potential. For a protein or chemical to accept electrons, it must have a more positive redox potential than the electron donor. Therefore, electrons move from electron carriers with more negative redox potential to those with more positive redox potential. The four major classes of electron carriers involved in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic electron transport systems are the cytochromes, flavoproteins, iron-sulfur proteins, and the quinones.

In aerobic respiration, the final electron acceptor (i.e., the one having the most positive redox potential) at the end of the ETS is an oxygen molecule $$O_2$$ that becomes reduced to water $$H_2O$$ by the final ETS carrier. This electron carrier, cytochrome oxidase, differs between bacterial types and can be used to differentiate closely related bacteria for diagnoses. For example, the gram-negative opportunist Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the gram-negative cholera- causing Vibrio cholerae use cytochrome c oxidase, which can be detected by the oxidase test, whereas other gram- negative Enterobacteriaceae, like E. coli, are negative for this test because they produce different cytochrome oxidase types.

There are many circumstances under which aerobic respiration is not possible, including any one or more of the following:

- The cell lacks genes encoding an appropriate cytochrome oxidase for transferring electrons to oxygen at the end of the electron transport system.

- The cell lacks genes encoding enzymes to minimize the severely damaging effects of dangerous oxygen radicals produced during aerobic respiration, such as hydrogen peroxide $$H_2O_2$$ or superoxide $$O_2-$$.

- The cell lacks a sufficient amount of oxygen to carry out aerobic respiration.

One possible alternative to aerobic respiration is anaerobic respiration, using an inorganic molecule other than oxygen as a final electron acceptor. There are many types of anaerobic respiration found in bacteria and archaea.

Denitrifiers are important soil bacteria that use nitrate $$NO_3-$$ and nitrite $$NO_2-$$ as final electron acceptors, producing nitrogen gas $$N_2$$. Many aerobically respiring bacteria, including E. coli, switch to using nitrate as a final electron acceptor and producing nitrite when oxygen levels have been depleted.

Microbes using anaerobic respiration commonly have an intact Krebs cycle, so these organisms can access the energy of the NADH and FADH2 molecules formed. However, anaerobic respirers use altered ETS carriers encoded by their genomes, including distinct complexes for electron transfer to their final electron acceptors. Smaller electrochemical gradients are generated from these electron transfer systems, so less ATP is formed through anaerobic respiration.

Check Your Understanding

- Do both aerobic respiration and anaerobic respiration use an electron transport chain?

Chemiosmosis, Proton Motive Force, and Oxidative Phosphorylation

In each transfer of an electron through the ETS, the electron loses energy, but with some transfers, the energy is stored as potential energy by using it to pump hydrogen ions (H+) across a membrane. In prokaryotic cells, H+ is pumped to the outside of the cytoplasmic membrane (called the periplasmic space in gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria), and in eukaryotic cells, they are pumped from the mitochondrial matrix across the inner mitochondrial membrane into the intermembrane space. There is an uneven distribution of H+ across the membrane that establishes an electrochemical gradient because H+ ions are positively charged (electrical) and there is a higher concentration (chemical) on one side of the membrane. This electrochemical gradient formed by the accumulation of H+ (also known as a proton) on one side of the membrane compared with the other is referred to as the proton motive force (PMF). Because the ions involved are H+, a pH gradient is also established, with the side of the membrane having the higher concentration of H+ being more acidic. Beyond the use of the PMF to make ATP, as discussed in this chapter, the PMF can also be used to drive other energetically unfavorable processes, including nutrient transport and flagella rotation for motility.

The potential energy of this electrochemical gradient generated by the ETS causes the H+ to diffuse across a membrane (the plasma membrane in prokaryotic cells and the inner membrane in mitochondria in eukaryotic cells). This flow of hydrogen ions across the membrane, called chemiosmosis, must occur through a channel in the membrane via a membrane-bound enzyme complex called ATP synthase (Figure 8.15). The tendency for movement in this way is much like water accumulated on one side of a dam, moving through the dam when opened. ATP synthase (like a combination of the intake and generator of a hydroelectric dam) is a complex protein that acts as a tiny generator, turning by the force of the H+ diffusing through the enzyme, down their electrochemical gradient from where there are many mutually repelling H+ to where there are fewer H+. In prokaryotic cells, H+ flows from the outside of the cytoplasmic membrane into the cytoplasm, whereas in eukaryotic mitochondria, H+ flows from the intermembrane space to the mitochondrial matrix. The turning of the parts of this molecular machine regenerates ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) by oxidative phosphorylation, a second mechanism for making ATP that harvests the potential energy stored within an electrochemical gradient.

The number of ATP molecules generated from the catabolism of glucose varies. For example, the number of hydrogen ions that the electron transport system complexes can pump through the membrane varies between different species of organisms. In aerobic respiration in mitochondria, the passage of electrons from one molecule of NADH generates enough proton motive force to make three ATP molecules by oxidative phosphorylation, whereas the passage of electrons from one molecule of FADH2 generates enough proton motive force to make only two ATP molecules. Thus, the 10 NADH molecules made per glucose during glycolysis, the transition reaction, and the Krebs cycle carry enough energy to make 30 ATP molecules, whereas the two FADH2 molecules made per glucose during these processes provide enough energy to make four ATP molecules. Overall, the theoretical maximum yield of ATP made during the complete aerobic respiration of glucose is 38 molecules, with four being made by substrate-level phosphorylation and 34 being made by oxidative phosphorylation (Table 8.2). In reality, the total ATP yield is usually less, ranging from one to 34 ATP molecules, depending on whether the cell is using aerobic respiration or anaerobic respiration; in eukaryotic cells, some energy is expended to transport intermediates from the cytoplasm into the mitochondria, affecting ATP yield.

Table 8.2 summarizes the theoretical maximum yields of ATP from various processes during the complete aerobic respiration of one glucose molecule.

| Source | Carbon Flow | Molecules of Reduced Coenzymes Produced | Net ATP molecules made by Substrate-Level Phosphorylation | Net ATP Molecules made by Oxidative Phosphorylation | Theoretical Maximum Yield of ATP Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis (EMP) | Glucose (6C) to 2 pyruvates (3C) | 2 NADH | 2 ATP | 6 ATP FROM 2 NADH | 8 |

| Transition Reaction | 2 PYRUVATES (3C) TO 2 ACETYL (2C) + 2 CO2 | 2 NADH | - | 6 ATP FROM 2 NADH | 6 |

| Krebs cycle | 2 acetyl (2C) to 4 CO2 | 6 NADH; 2 FADH2 | 2 ATP | 18 ATP from 6 NADH; 4ATP from 2 FADH2 | 24 |

| Total: | glucose (6C) to 6 CO2 | 10 NADH; 2 FADH2 | 4 ATP | 34 ATP | 38 ATP |

Check Your Understanding

- What are the functions of the proton motive force?