15.1 – Characteristics of Infectious Disease

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between signs and symptoms of disease

- Explain the difference between a communicable disease and a noncommunicable disease

- Compare different types of infectious diseases, including iatrogenic, nosocomial, and zoonotic diseases

- Identify and describe the stages of an acute infectious disease in terms of number of pathogens present and severity of signs and symptoms

A disease is any condition in which the normal structure or functions of the body are damaged or impaired. Physical injuries or disabilities are not classified as disease, but there can be several causes for disease, including infection by a pathogen, genetics (as in many cancers or deficiencies), noninfectious environmental causes, or inappropriate immune responses. Our focus in this chapter will be on infectious diseases, although when diagnosing infectious diseases, it is always important to consider possible noninfectious causes.

Signs and Symptoms of Disease

An infection is the successful colonization of a host by a microorganism. Infections can lead to disease, which causes signs and symptoms resulting in a deviation from the normal structure or functioning of the host. Microorganisms that can cause disease are known as pathogens.

The signs of disease are objective and measurable, and can be directly observed by a clinician. Vital signs, which are used to measure the body’s basic functions, include body temperature (normally 37 °C [98.6 °F]), heart rate (normally 60–100 beats per minute), breathing rate (normally 12–18 breaths per minute), and blood pressure (normally between 90/60 and 120/80 mm Hg). Changes in any of the body’s vital signs may be indicative of disease. For example, having a fever (a body temperature significantly higher than 37 °C or 98.6 °F) is a sign of disease because it can be measured.

In addition to changes in vital signs, other observable conditions may be considered signs of disease. For example, the presence of antibodies in a patient’s serum (the liquid portion of blood that lacks clotting factors) can be observed and measured through blood tests and, therefore, can be considered a sign. However, it is important to note that the presence of antibodies is not always a sign of an active disease. Antibodies can remain in the body long after an infection has resolved; also, they may develop in response to a pathogen that is in the body but not currently causing disease.

Unlike signs, symptoms of disease are subjective. Symptoms are felt or experienced by the patient, but they cannot be clinically confirmed or objectively measured. Examples of symptoms include nausea, loss of appetite, and pain. Such symptoms are important to consider when diagnosing disease, but they are subject to memory bias and are difficult to measure precisely. Some clinicians attempt to quantify symptoms by asking patients to assign a numerical value to their symptoms. For example, the Wong-Baker Faces pain-rating scale asks patients to rate their pain on a scale of 0–10. An alternative method of quantifying pain is measuring skin conductance fluctuations. These fluctuations reflect sweating due to skin sympathetic nerve activity resulting from the stressor of pain.[1]

A specific group of signs and symptoms characteristic of a particular disease is called a syndrome. Many syndromes are named using a nomenclature based on signs and symptoms or the location of the disease. Table 15.1 lists some of the prefixes and suffixes commonly used in naming syndromes.

| Affix | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| cyto- | cell | cytopenia: reduction in the number of blood cells |

| hepat- | of the liver | hepatitis: inflammation of the liver |

| -pathy | disease | neuropathy: a disease affecting nerves |

| -emia | of the blood | bacteremia: presence of bacteria in blood |

| -itis | inflammation | colitis: inflammation of the colon |

| -lysis | destruction | hemolysis: destruction of red blood cells |

| -oma | tumor | lymphoma: cancer of the lymphatic system |

| -osis | diseased or abnormal condition | leukocytosis: abnormally high number of white blood cells |

| -derma | of the skin | keratoderma: a thickening of the skin |

Clinicians must rely on signs and on asking questions about symptoms, medical history, and the patient’s recent activities to identify a particular disease and the potential causative agent. Diagnosis is complicated by the fact that different microorganisms can cause similar signs and symptoms in a patient. For example, an individual presenting with symptoms of diarrhea may have been infected by one of a wide variety of pathogenic microorganisms. Bacterial pathogens associated with diarrheal disease include Vibrio cholerae, Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter jejuni, and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC). Viral pathogens associated with diarrheal disease include norovirus and rotavirus. Parasitic pathogens associated with diarrhea include Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium parvum. Likewise, fever is indicative of many types of infection, from the common cold to the deadly Ebola hemorrhagic fever.

Finally, some diseases may be asymptomatic or subclinical, meaning they do not present any noticeable signs or symptoms. For example, most individual infected with herpes simplex virus remain asymptomatic and are unaware that they have been infected.

Check Your Understanding

- Explain the difference between signs and symptoms.

Classifications of Disease

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is used in clinical fields to classify diseases and monitor morbidity (the number of cases of a disease) and mortality (the number of deaths due to a disease). In this section, we will introduce terminology used by the ICD (and in health-care professions in general) to describe and categorize various types of disease.

An infectious disease is any disease caused by the direct effect of a pathogen. A pathogen may be cellular (bacteria, parasites, and fungi) or acellular (viruses, viroids, and prions). Some infectious diseases are also communicable, meaning they are capable of being spread from person to person through either direct or indirect mechanisms. Some infectious communicable diseases are also considered contagious diseases, meaning they are easily spread from person to person. Not all contagious diseases are equally so; the degree to which a disease is contagious usually depends on how the pathogen is transmitted. For example, measles is a highly contagious viral disease that can be transmitted when an infected person coughs or sneezes and an uninfected person breathes in droplets containing the virus. Gonorrhea is not as contagious as measles because transmission of the pathogen (Neisseria gonorrhoeae) requires close intimate contact (usually sexual) between an infected person and an uninfected person.

Diseases that are contracted as the result of a medical procedure are known as iatrogenic diseases. Iatrogenic diseases can occur after procedures involving wound treatments, catheterization, or surgery if the wound or surgical site becomes contaminated. For example, an individual treated for a skin wound might acquire necrotizing fasciitis (an aggressive, “flesh-eating” disease) if bandages or other dressings became contaminated by Clostridium perfringens or one of several other bacteria that can cause this condition.

Diseases acquired in hospital settings are known as nosocomial diseases. Several factors contribute to the prevalence and severity of nosocomial diseases. First, sick patients bring numerous pathogens into hospitals, and some of these pathogens can be transmitted easily via improperly sterilized medical equipment, bed sheets, call buttons, door handles, or by clinicians, nurses, or therapists who do not wash their hands before touching a patient. Second, many hospital patients have weakened immune systems, making them more susceptible to infections. Compounding this, the prevalence of antibiotics in hospital settings can select for drug-resistant bacteria that can cause very serious infections that are difficult to treat.

Certain infectious diseases are not transmitted between humans directly but can be transmitted from animals to humans. Such a disease is called zoonotic disease (or zoonosis). According to WHO, a zoonosis is a disease that occurs when a pathogen is transferred from a vertebrate animal to a human; however, sometimes the term is defined more broadly to include diseases transmitted by all animals (including invertebrates). For example, rabies is a viral zoonotic disease spread from animals to humans through bites and contact with infected saliva. Many other zoonotic diseases rely on insects or other arthropods for transmission. Examples include yellow fever (transmitted through the bite of mosquitoes infected with yellow fever virus) and Rocky Mountain spotted fever (transmitted through the bite of ticks infected with Rickettsia rickettsii).

In contrast to communicable infectious diseases, a noncommunicable infectious disease is not spread from one person to another. One example is tetanus, caused by Clostridium tetani, a bacterium that produces endospores that can survive in the soil for many years. This disease is typically only transmitted through contact with a skin wound; it cannot be passed from an infected person to another person. Similarly, Legionnaires disease is caused by Legionella pneumophila, a bacterium that lives within amoebae in moist locations like water-cooling towers. An individual may contract Legionnaires disease via contact with the contaminated water, but once infected, the individual cannot pass the pathogen to other individuals.

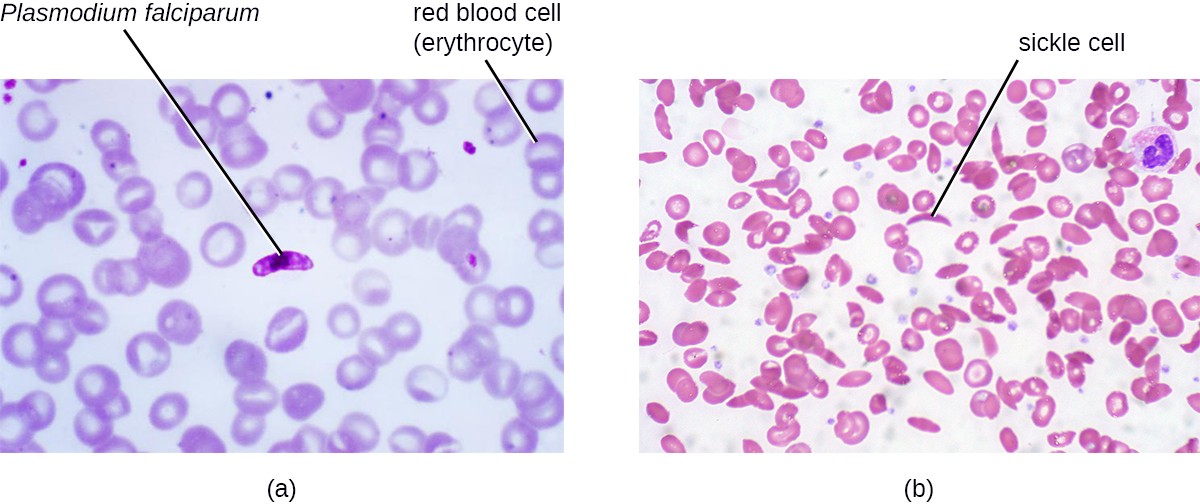

In addition to the wide variety of noncommunicable infectious diseases, noninfectious diseases (those not caused by pathogens) are an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Noninfectious diseases can be caused by a wide variety factors, including genetics, the environment, or immune system dysfunction, to name a few. For example, sickle cell anemia is an inherited disease caused by a genetic mutation that can be passed from parent to offspring (Figure 15.2). Other types of noninfectious diseases are listed in Table 15.2.

Types of Noninfectious Diseases

| Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Inherited | A genetic disease | Sickle cell anemia |

| Congenital | Disease that is present at or before birth | Down syndrome |

| Degenerative | Progressive, irreversible loss of function | Parkinson disease (affecting central nervous system) |

| Nutritional deficiency | Impaired body function due to lack of nutrients | Scurvy (vitamin C deficiency) |

| Endocrine | Disease involving malfunction of glands that release hormones to regulate body functions | Hypothyroidism – thyroid does not produce enough thyroid hormone, which is important for metabolism |

| Neoplastic | Abnormal growth (benign or malignant) | Some forms of cancer |

| Idiopathic | Disease for which the cause is unknown | Idiopathic juxtafoveal retinal telangiectasia (dilated, twisted blood vessels in the retina of the eye) |

a) A micrograph showing round red blood cells (erythrocytes) and a darker oval cell (Plasmodium falciparum).b) A micrograph showing round red blood cells and a “C” shaped red blood cell labeled “sickle cell”.

Link to Learning

Lists of common infectious diseases can be found at the following websites:

Check Your Understanding

- Describe how a disease can be infectious but not contagious.

- Explain the difference between iatrogenic disease and nosocomial disease.

Periods of Disease

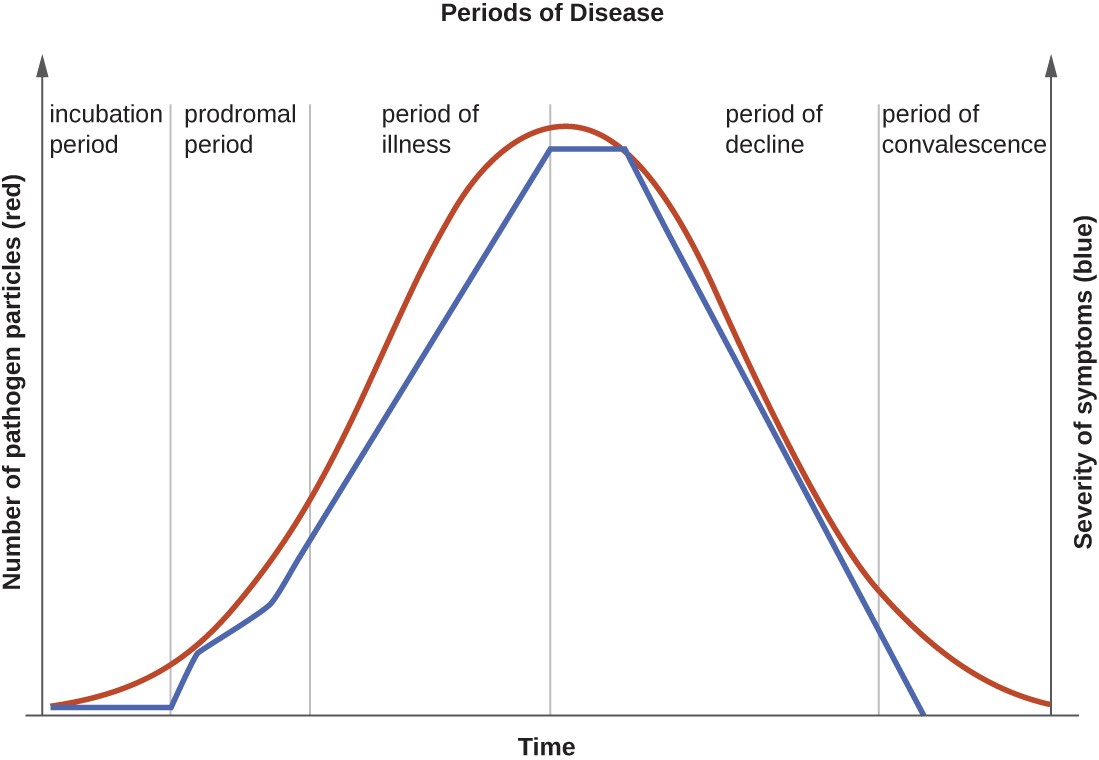

The five periods of disease (sometimes referred to as stages or phases) include the incubation, prodromal, illness, decline, and convalescence periods (Figure 15.3). The incubation period occurs in an acute disease after the initial entry of the pathogen into the host (patient). It is during this time the pathogen begins multiplying in the host. However, there are insufficient numbers of pathogen particles (cells or viruses) present to cause signs and symptoms of disease. Incubation periods can vary from a day or two in acute disease to months or years in chronic disease, depending upon the pathogen. Factors involved in determining the length of the incubation period are diverse, and can include strength of the pathogen, strength of the host immune defenses, site of infection, type of infection, and the size infectious dose received. During this incubation period, the patient is unaware that a disease is beginning to develop.

alt=”A graph titled “Periods of Disease” with time on the X axis and two separate Y-axes: number of pathogen particles (red) and severity of symptoms (blue). Both of these lines mirror each other and have a general bell shape. The first stage is incubation period when there are few pathogens and symptoms are mild. The next stage is prodromal period when the number of pathogens is increasing and symptoms are becoming more severe. The next stage is period of illness where numbers of pathogens and symptoms both continue to increase. The next stage is period of decline in infection where the number of pathogens is decreasing and symptoms are becoming less severe. The final stage is period of convalescence when symptoms go away and the number of pathogens decrease. Note that there are still pathogens present even after there are no more symptoms of the disease.”

The prodromal period occurs after the incubation period. During this phase, the pathogen continues to multiply and the host begins to experience general signs and symptoms of illness, which typically result from activation of the immune system, such as fever, pain, soreness, swelling, or inflammation. Usually, such signs and symptoms are too general to indicate a particular disease. Following the prodromal period is the period of illness, during which the signs and symptoms of disease are most obvious and severe.

The period of illness is followed by the period of decline, during which the number of pathogen particles begins to decrease, and the signs and symptoms of illness begin to decline. However, during the decline period, patients may become susceptible to developing secondary infections because their immune systems have been weakened by the primary infection. The final period is known as the period of convalescence. During this stage, the patient generally returns to normal functions, although some diseases may inflict permanent damage that the body cannot fully repair.

Infectious diseases can be contagious during all five of the periods of disease. Which periods of disease are more likely to associated with transmissibility of an infection depends upon the disease, the pathogen, and the mechanisms by which the disease develops and progresses. For example, with meningitis (infection of the lining of brain), the periods of infectivity depend on the type of pathogen causing the infection. Patients with bacterial meningitis are contagious during the incubation period for up to a week before the onset of the prodromal period, whereas patients with viral meningitis become contagious when the first signs and symptoms of the prodromal period appear. With many viral diseases associated with rashes (e.g., chickenpox, measles, rubella, roseola), patients are contagious during the incubation period up to a week before the rash develops. In contrast, with many respiratory infections (e.g., colds, influenza, diphtheria, strep throat, and pertussis) the patient becomes contagious with the onset of the prodromal period. Depending upon the pathogen, the disease, and the individual infected, transmission can still occur during the periods of decline, convalescence, and even long after signs and symptoms of the disease disappear. For example, an individual recovering from a diarrheal disease may continue to carry and shed the pathogen in feces for some time, posing a risk of transmission to others through direct contact or indirect contact (e.g., through contaminated objects or food).

Check Your Understanding

- Name some of the factors that can affect the length of the incubation period of a particular disease.

Acute and Chronic Diseases

The duration of the period of illness can vary greatly, depending on the pathogen, effectiveness of the immune response in the host, and any medical treatment received. For an acute disease, pathologic changes occur over a relatively short time (e.g., hours, days, or a few weeks) and involve a rapid onset of disease conditions. For example, influenza (caused by Influenzavirus) is considered an acute disease because the incubation period is approximately 1–2 days. Infected individuals can spread influenza to others for approximately 5 days after becoming ill. After approximately 1 week, individuals enter the period of decline.

For a chronic disease, pathologic changes can occur over longer time spans (e.g., months, years, or a lifetime). For example, chronic gastritis (inflammation of the lining of the stomach) is caused by the gram-negative bacterium Helicobacter pylori. H. pylori is able to colonize the stomach and persist in its highly acidic environment by producing the enzyme urease, which modifies the local acidity, allowing the bacteria to survive indefinitely.[2] Consequently, H. pylori infections can recur indefinitely unless the infection is cleared using antibiotics.[3] Hepatitis B virus can cause a chronic infection in some patients who do not eliminate the virus after the acute illness. A chronic infection with hepatitis B virus is characterized by the continued production of infectious virus for 6 months or longer after the acute infection, as measured by the presence of viral antigen in blood samples.

In latent diseases, as opposed to chronic infections, the causal pathogen goes dormant for extended periods of time with no active replication. Examples of diseases that go into a latent state after the acute infection include herpes (herpes simplex viruses [HSV-1 and HSV-2]), chickenpox (varicella-zoster virus [VZV]), and mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]). HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV evade the host immune system by residing in a latent form within cells of the nervous system for long periods of time, but they can reactivate to become active infections during times of stress and immunosuppression. For example, an initial infection by VZV may result in a case of childhood chickenpox, followed by a long period of latency. The virus may reactivate decades later, causing episodes of shingles in adulthood. EBV goes into latency in B cells of the immune system and possibly epithelial cells; it can reactivate years later to produce B-cell lymphoma.

Check Your Understanding

- Explain the difference between latent disease and chronic disease.

Footnotes

F. Savino et al. “Pain Assessment in Children Undergoing Venipuncture: The Wong–Baker Faces Scale Versus Skin Conductance Fluctuations.” PeerJ 1 (2013):e37; https://peerj.com/articles/37/

J.G. Kusters et al. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 19 no. 3 (2006):449–490.

N.R. Salama et al. “Life in the Human Stomach: Persistence Strategies of the Bacterial Pathogen Helicobacter pylori.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 11 (2013):385–399.