14.5 – Drug Resistance

Learning Objectives

- Explain the concept of drug resistance

- Describe how microorganisms develop or acquire drug resistance

- Describe the different mechanisms of antimicrobial drug resistance

Antimicrobial resistance is not a new phenomenon. In nature, microbes are constantly evolving in order to overcome the antimicrobial compounds produced by other microorganisms. Human development of antimicrobial drugs and their widespread clinical use has simply provided another selective pressure that promotes further evolution. Several important factors can accelerate the evolution of drug resistance. These include the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials, inappropriate use of antimicrobials, subtherapeutic dosing, and patient noncompliance with the recommended course of treatment.

Exposure of a pathogen to an antimicrobial compound can select for chromosomal mutations conferring resistance, which can be transferred vertically to subsequent microbial generations and eventually become predominant in a microbial population that is repeatedly exposed to the antimicrobial. Alternatively, many genes responsible for drug resistance are found on plasmids or in transposons that can be transferred easily between microbes through horizontal gene transfer (see How Asexual Prokaryotes Achieve Genetic Diversity). Transposons also have the ability to move resistance genes between plasmids and chromosomes to further promote the spread of resistance.

Mechanisms for Drug Resistance

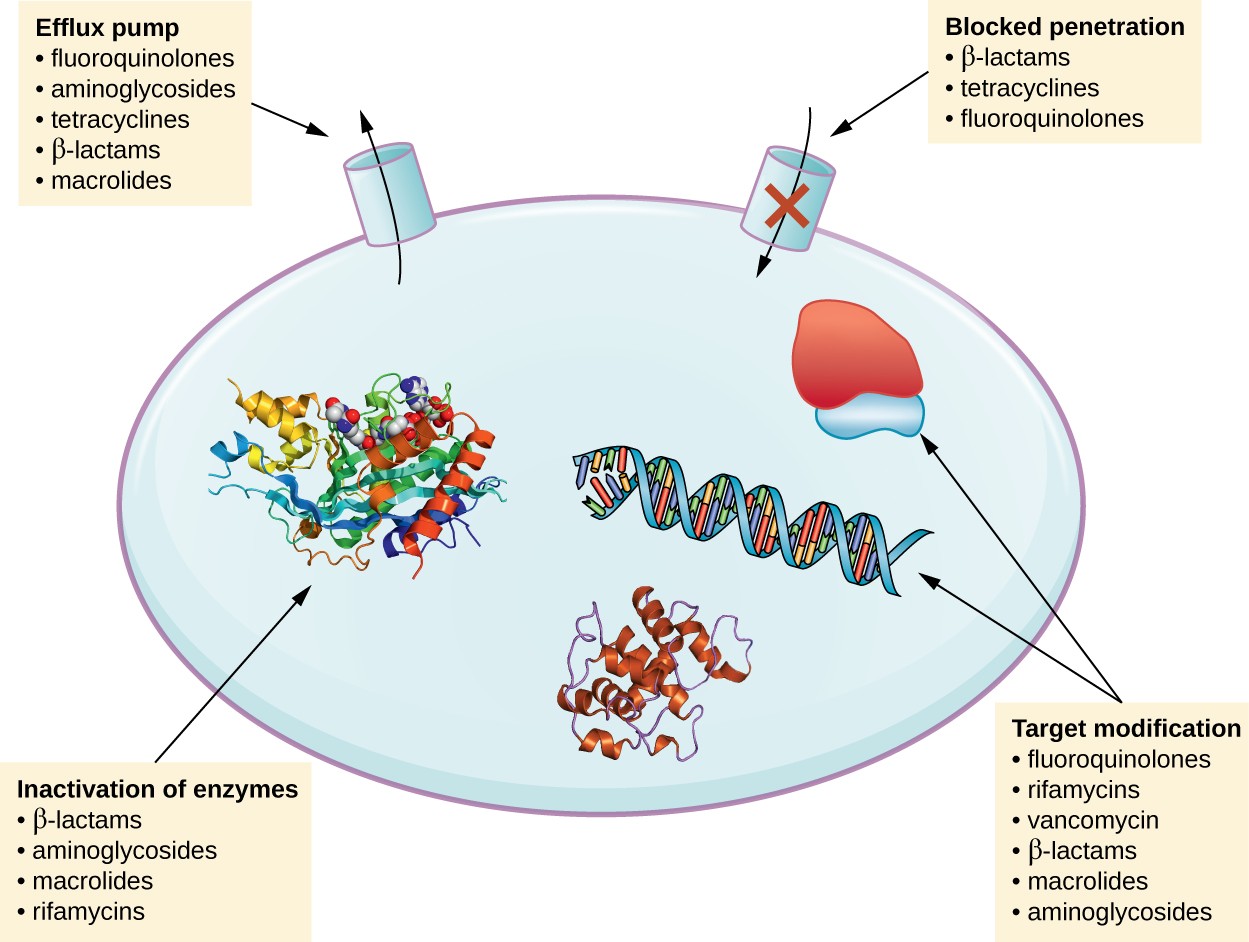

There are several common mechanisms for drug resistance, which are summarized in Figure 14.18. These mechanisms include enzymatic modification of the drug, modification of the antimicrobial target, and prevention of drug penetration or accumulation.

Mechanisms of resistance. Efflux pump (pumping drugs out of the cell): fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, Beta-lactams, macrolides. Blocked penetration (not letting drugs into the cell): beta-lactams, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones. Target modification (changing the target of the drug such as ribosomes or DNA): fluoroquinolones, rfamycins, vancomycin, beta-lactams, macrolides, aminoglycosides. Inactivating enzyme (enzyme that breaks down the drug): beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, macrolides, rifamycins.

Drug Modification or Inactivation

Resistance genes may code for enzymes that chemically modify an antimicrobial, thereby inactivating it, or destroy an antimicrobial through hydrolysis. Resistance to many types of antimicrobials occurs through this mechanism. For example, aminoglycoside resistance can occur through enzymatic transfer of chemical groups to the drug molecule, impairing the binding of the drug to its bacterial target. For β-lactams, bacterial resistance can involve the enzymatic hydrolysis of the β-lactam bond within the β-lactam ring of the drug molecule. Once the β-lactam bond is broken, the drug loses its antibacterial activity. This mechanism of resistance is mediated by β-lactamases, which are the most common mechanism of β-lactam resistance. Inactivation of rifampin commonly occurs through glycosylation, phosphorylation, or adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribosylation, and resistance to macrolides and lincosamides can also occur due to enzymatic inactivation of the drug or modification.

Prevention of Cellular Uptake or Efflux

Microbes may develop resistance mechanisms that involve inhibiting the accumulation of an antimicrobial drug, which then prevents the drug from reaching its cellular target. This strategy is common among gram-negative pathogens and can involve changes in outer membrane lipid composition, porin channel selectivity, and/or porin channel concentrations. For example, a common mechanism of carbapenem resistance among Pseudomonas aeruginosa is to decrease the amount of its OprD porin, which is the primary portal of entry for carbapenems through the outer membrane of this pathogen. Additionally, many gram-positive and gram-negative pathogenic bacteria produce efflux pumps that actively transport an antimicrobial drug out of the cell and prevent the accumulation of drug to a level that would be antibacterial. For example, resistance to β-lactams, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones commonly occurs through active efflux out of the cell, and it is rather common for a single efflux pump to have the ability to translocate multiple types of antimicrobials.

Target Modification

Because antimicrobial drugs have very specific targets, structural changes to those targets can prevent drug binding, rendering the drug ineffective. Through spontaneous mutations in the genes encoding antibacterial drug targets, bacteria have an evolutionary advantage that allows them to develop resistance to drugs. This mechanism of resistance development is quite common. Genetic changes impacting the active site of penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) can inhibit the binding of β-lactam drugs and provide resistance to multiple drugs within this class. This mechanism is very common among strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, which alter their own PBPs through genetic mechanisms. In contrast, strains of Staphylococcus aureus develop resistance to methicillin (MRSA) through the acquisition of a new low-affinity PBP, rather than structurally alter their existing PBPs. Not only does this new low-affinity PBP provide resistance to methicillin but it provides resistance to virtually all β-lactam drugs, with the exception of the newer fifth-generation cephalosporins designed specifically to kill MRSA. Other examples of this resistance strategy include alterations in

- ribosome subunits, providing resistance to macrolides, tetracyclines, and aminoglycosides;

- lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure, providing resistance to polymyxins;

- RNA polymerase, providing resistance to rifampin;

- DNA gyrase, providing resistance to fluoroquinolones;

- metabolic enzymes, providing resistance to sulfa drugs, sulfones, and trimethoprim; and

- peptidoglycan subunit peptide chains, providing resistance to glycopeptides.

Target Overproduction or Enzymatic Bypass

When an antimicrobial drug functions as an antimetabolite, targeting a specific enzyme to inhibit its activity, there are additional ways that microbial resistance may occur. First, the microbe may overproduce the target enzyme such that there is a sufficient amount of antimicrobial-free enzyme to carry out the proper enzymatic reaction. Second, the bacterial cell may develop a bypass that circumvents the need for the functional target enzyme. Both of these strategies have been found as mechanisms of sulfonamide resistance. Vancomycin resistance among S. aureus has been shown to involve the decreased cross-linkage of peptide chains in the bacterial cell wall, which provides an increase in targets for vancomycin to bind to in the outer cell wall. Increased binding of vancomycin in the outer cell wall provides a blockage that prevents free drug molecules from penetrating to where they can block new cell wall synthesis.

Target Mimicry

A recently discovered mechanism of resistance called target mimicry involves the production of proteins that bind and sequester drugs, preventing the drugs from binding to their target. For example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces a protein with regular pentapeptide repeats that appears to mimic the structure of DNA. This protein binds fluoroquinolones, sequestering them and keeping them from binding to DNA, providing M. tuberculosis resistance to fluoroquinolones. Proteins that mimic the A-site of the bacterial ribosome have been found to contribute to aminoglycoside resistance as well.[1]

Check Your Understanding

- List several mechanisms for drug resistance.

Multidrug-Resistant Microbes and Cross Resistance

From a clinical perspective, our greatest concerns are multidrug-resistant microbes (MDRs) and cross resistance. MDRs are colloquially known as “superbugs” and carry one or more resistance mechanism(s), making them resistant to multiple antimicrobials. In cross-resistance, a single resistance mechanism confers resistance to multiple antimicrobial drugs. For example, having an efflux pump that can export multiple antimicrobial drugs is a common way for microbes to be resistant to multiple drugs by using a single resistance mechanism. In recent years, several clinically important superbugs have emerged, and the CDC reports that superbugs are responsible for more than 2 million infections in the US annually, resulting in at least 23,000 fatalities.[2] Several of the superbugs discussed in the following sections have been dubbed the ESKAPE pathogens. This acronym refers to the names of the pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter spp.) but it is also fitting in that these pathogens are able to “escape” many conventional forms of antimicrobial therapy. As such, infections by ESKAPE pathogens can be difficult to treat and they cause a large number of nosocomial infections.

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

Methicillin, a semisynthetic penicillin, was designed to resist inactivation by β-lactamases. Unfortunately, soon after the introduction of methicillin to clinical practice, methicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus appeared and started to spread. The mechanism of resistance, acquisition of a new low-affinity PBP, provided S. aureus with resistance to all available β-lactams. Strains of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) are widespread opportunistic pathogens and a particular concern for skin and other wound infections, but may also cause pneumonia and septicemia. Although originally a problem in health-care settings (hospital-acquired MRSA [HA-MRSA]), MRSA infections are now also acquired through contact with contaminated members of the general public, called community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA). Approximately one-third of the population carries S. aureus as a member of their normal nasal microbiota without illness, and about 6% of these strains are methicillin resistant.[3][4]

Micro Connections

Clavulanic Acid: Penicillin’s Little Helper

With the introduction of penicillin in the early 1940s, and its subsequent mass production, society began to think of antibiotics as miracle cures for a wide range of infectious diseases. Unfortunately, as early as 1945, penicillin resistance was first documented and started to spread. Greater than 90% of current S. aureus clinical isolates are resistant to penicillin.[5]Although developing new antimicrobial drugs is one solution to this problem, scientists have explored new approaches, including the development of compounds that inactivate resistance mechanisms. The development of clavulanic acid represents an early example of this strategy. Clavulanic acid is a molecule produced by the bacterium Streptococcus clavuligerus. It contains a β-lactam ring, making it structurally similar to penicillin and other β-lactams, but shows no clinical effectiveness when administered on its own. Instead, clavulanic acid binds irreversibly within the active site of β-lactamases and prevents them from inactivating a coadministered penicillin.

Clavulanic acid was first developed in the 1970s and was mass marketed in combination with amoxicillin beginning in the 1980s under the brand name Augmentin. As is typically the case, resistance to the amoxicillin- clavulanic acid combination soon appeared. Resistance most commonly results from bacteria increasing production of their β-lactamase and overwhelming the inhibitory effects of clavulanic acid, mutating their β- lactamase so it is no longer inhibited by clavulanic acid, or from acquiring a new β-lactamase that is not inhibited by clavulanic acid. Despite increasing resistance concerns, clavulanic acid and related β-lactamase inhibitors (sulbactam and tazobactam) represent an important new strategy: the development of compounds that directly inhibit antimicrobial resistance-conferring enzymes.

Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus

Vancomycin is only effective against gram-positive organisms, and it is used to treat wound infections, septic infections, endocarditis, and meningitis that are caused by pathogens resistant to other antibiotics. It is considered one of the last lines of defense against such resistant infections, including MRSA. With the rise of antibiotic resistance in the 1970s and 1980s, vancomycin use increased, and it is not surprising that we saw the emergence and spread of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA), and vancomycin- intermediate S. aureus (VISA). The mechanism of vancomycin resistance among enterococci is target modification involving a structural change to the peptide component of the peptidoglycan subunits, preventing vancomycin from binding. These strains are typically spread among patients in clinical settings by contact with health-care workers and contaminated surfaces and medical equipment.

VISA and VRSA strains differ from each other in the mechanism of resistance and the degree of resistance each mechanism confers. VISA strains exhibit intermediate resistance, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 4–8 μg/mL, and the mechanism involves an increase in vancomycin targets. VISA strains decrease the crosslinking of peptide chains in the cell wall, providing an increase in vancomycin targets that trap vancomycin in the outer cell wall. In contrast, VRSA strains acquire vancomycin resistance through horizontal transfer of resistance genes from VRE, an opportunity provided in individuals coinfected with both VRE and MRSA. VRSA exhibit a higher level of resistance, with MICs of 16 μg/mL or higher.[6] In the case of all three types of vancomycin-resistant bacteria, rapid clinical identification is necessary so proper procedures to limit spread can be implemented. The oxazolidinones like linezolid are useful for the treatment of these vancomycin-resistant, opportunistic pathogens, as well as MRSA.

Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase–Producing Gram-Negative Pathogens

Gram-negative pathogens that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) show resistance well beyond just penicillins. The spectrum of β-lactams inactivated by ESBLs provides for resistance to all penicillins, cephalosporins, monobactams, and the β-lactamase-inhibitor combinations, but not the carbapenems. An even greater concern is that the genes encoding for ESBLs are usually found on mobile plasmids that also contain genes for resistance to other drug classes (e.g., fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines), and may be readily spread to other bacteria by horizontal gene transfer. These multidrug-resistant bacteria are members of the intestinal microbiota of some individuals, but they are also important causes of opportunistic infections in hospitalized patients, from whom they can be spread to other people.

Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria

The occurrence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and carbapenem resistance among other gram- negative bacteria (e.g., P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Stenotrophomonas maltophila) is a growing health- care concern. These pathogens develop resistance to carbapenems through a variety of mechanisms, including production of carbapenemases (broad-spectrum β-lactamases that inactivate all β-lactams, including carbapenems), active efflux of carbapenems out of the cell, and/or prevention of carbapenem entry through porin channels. Similar to concerns with ESBLs, carbapenem-resistant, gram-negative pathogens are usually resistant to multiple classes of antibacterials, and some have even developed pan-resistance (resistance to all available antibacterials). Infections with carbapenem-resistant, gram-negative pathogens commonly occur in health-care settings through interaction with contaminated individuals or medical devices, or as a result of surgery.

Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The emergence of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (XDR-TB) is also of significant global concern. MDR-TB strains are resistant to both rifampin and isoniazid, the drug combination typically prescribed for treatment of tuberculosis. XDR-TB strains are additionally resistant to any fluoroquinolone and at least one of three other drugs (amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin) used as a second line of treatment, leaving these patients very few treatment options. Both types of pathogens are particularly problematic in immunocompromised persons, including those suffering from HIV infection. The development of resistance in these strains often results from the incorrect use of antimicrobials for tuberculosis treatment, selecting for resistance.

Check Your Understanding

- How does drug resistance lead to superbugs?

Link to Learning

To learn more about the top 18 drug-resistant threats to the US, visit the CDC’s website.

Micro Connections

Factory Farming and Drug Resistance

Although animal husbandry has long been a major part of agriculture in America, the rise of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) since the 1950s has brought about some new environmental issues, including the contamination of water and air with biological waste, and ethical issues regarding animal rights also are associated with growing animals in this way. Additionally, the increase in CAFOs involves the extensive use of antimicrobial drugs in raising livestock. Antimicrobials are used to prevent the development of infectious disease in the close quarters of CAFOs; however, the majority of antimicrobials used in factory farming are for the promotion of growth—in other words, to grow larger animals.

The mechanism underlying this enhanced growth remains unclear. These antibiotics may not necessarily be the same as those used clinically for humans, but they are structurally related to drugs used for humans. As a result, use of antimicrobial drugs in animals can select for antimicrobial resistance, with these resistant bacteria becoming cross-resistant to drugs typically used in humans. For example, tylosin use in animals appears to select for bacteria also cross-resistant to other macrolides, including erythromycin, commonly used in humans.

Concentrations of the drug-resistant bacterial strains generated by CAFOs become increased in water and soil surrounding these farms. If not directly pathogenic in humans, these resistant bacteria may serve as a reservoir of mobile genetic elements that can then pass resistance genes to human pathogens. Fortunately, the cooking process typically inactivates any antimicrobials remaining in meat, so humans typically are not directly ingesting these drugs. Nevertheless, many people are calling for more judicious use of these drugs, perhaps charging farmers user fees to reduce indiscriminate use. In fact, in 2012, the FDA published guidelines for farmers who voluntarily phase out the use of antimicrobial drugs except under veterinary supervision and when necessary to ensure animal health. Although following the guidelines is voluntary at this time, the FDA does recommend what it calls “judicious” use of antimicrobial drugs in food-producing animals in an effort to decrease antimicrobial resistance.

Footnotes

D.H. Fong, A.M. Berghuis. “Substrate Promiscuity of an Aminoglycoside Antibiotic Resistance Enzyme Via Target Mimicry.” EMBO

Journal 21 no. 10 (2002):2323–2331.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Antibiotic/Antimicrobial Resistance.” http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/index.html. Accessed June 2, 2016.

A.S. Kalokhe et al. “Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis Drug Susceptibility and Molecular Diagnostic Testing: A Review of the Literature. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 345 no. 2 (2013):143–148.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): General Information About MRSA in the Community.” http://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/community/index.html. Accessed June 2, 2016

F.D. Lowy. “Antimicrobial Resistance: The Example of Staphylococcus aureus.” Journal of Clinical Investigation 111 no. 9 (2003):1265–1273.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Healthcare-Associated Infections (HIA): General Information about VISA/VRSA.” http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/organisms/visa_vrsa/visa_vrsa.html. Accessed June 2, 2016.