8.1 – Energy, Matter, and Enzymes

Learning Objectives

- Define and describe metabolism

- Compare and contrast autotrophs and heterotrophs

- Describe the importance of oxidation-reduction reactions in metabolism

- Describe why ATP, FAD, NAD+, and NADP+ are important in a cell

- Identify the structure and structural components of an enzyme

- Describe the differences between competitive and noncompetitive enzyme inhibitors

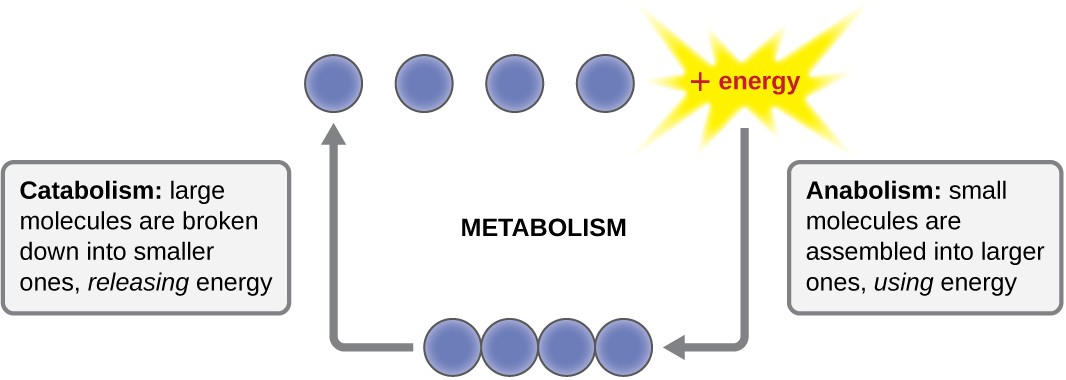

The term used to describe all of the chemical reactions inside a cell is metabolism (Figure 8.2). Cellular processes such as the building or breaking down of complex molecules occur through series of stepwise, interconnected chemical reactions called metabolic pathways. Reactions that are spontaneous and release energy are exergonic reactions, whereas endergonic reactions require energy to proceed. The term anabolism refers to those endergonic metabolic pathways involved in biosynthesis, converting simple molecular building blocks into more complex molecules, and fueled by the use of cellular energy. Conversely, the term catabolism refers to exergonic pathways that break down complex molecules into simpler ones. Molecular energy stored in the bonds of complex molecules is released in catabolic pathways and harvested in such a way that it can be used to produce high-energy molecules, which are used to drive anabolic pathways. Thus, in terms of energy and molecules, cells are continually balancing catabolism with anabolism.

Classification by Carbon and Energy Source

Organisms can be identified according to the source of carbon they use for metabolism as well as their energy source. The prefixes auto- (“self”) and hetero- (“other”) refer to the origins of the carbon sources various organisms can use. Organisms that convert inorganic carbon dioxide (CO2) into organic carbon compounds are autotrophs. Plants and cyanobacteria are well-known examples of autotrophs. Conversely, heterotrophs rely on more complex organic carbon compounds as nutrients; these are provided to them initially by autotrophs. Many organisms, ranging from humans to many prokaryotes, including the well-studied Escherichia coli, are heterotrophic.

Organisms can also be identified by the energy source they use. All energy is derived from the transfer of electrons, but the source of electrons differs between various types of organisms. The prefixes photo- (“light”) and chemo- (“chemical”) refer to the energy sources that various organisms use. Those that get their energy for electron transfer from light are phototrophs, whereas chemotrophs obtain energy for electron transfer by breaking chemical bonds. There are two types of chemotrophs: organotrophs and lithotrophs. Organotrophs, including humans, fungi, and many prokaryotes, are chemotrophs that obtain energy from organic compounds. Lithotrophs (“litho” means “rock”) are chemotrophs that get energy from inorganic compounds, including hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and reduced iron. Lithotrophy is unique to the microbial world.

The strategies used to obtain both carbon and energy can be combined for the classification of organisms according to nutritional type. Most organisms are chemoheterotrophs because they use organic molecules as both their electron and carbon sources. Table 8.1 summarizes this and the other classifications.

Classifications of Organisms by Energy and Carbon Source

| Chemo/Photo | Auto/Hetero | Energy Source | Carbon Source | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotroph | Chemoautotroph | Chemical | Inorganic | Hydrogen-, sulfur-, iron-, nitrogen-, and carbon monoxide-oxidizing bacteria |

| Chemotroph | Chemoheterotroph | Chemical | Organic compounds | All animals, most fungi, protozoa, and bacteria |

| Phototroph | Photoautotrophs | Light | Inorganic | All plants, algae, cyanobacteria, and green and purple sulfur bacteria |

| Phototroph | Photoheterotrophs | Light | Organic compounds | Green and purple nonsulfur bacteria, heliobacteria |

Check Your Understanding

- Explain the difference between catabolism and anabolism.

- Explain the difference between autotrophs and heterotrophs.

Oxidation and Reduction in Metabolism

The transfer of electrons between molecules is important because most of the energy stored in atoms and used to fuel cell functions is in the form of high-energy electrons. The transfer of energy in the form of electrons allows the cell to transfer and use energy incrementally; that is, in small packages rather than a single, destructive burst. Reactions that remove electrons from donor molecules, leaving them oxidized, are oxidation reactions; those that add electrons to acceptor molecules, leaving them reduced, are reduction reactions. Because electrons can move from one molecule to another, oxidation and reduction occur in tandem. These pairs of reactions are called oxidation-reduction reactions, or redox reactions.

Energy Carriers: NAD+, NADP+, FAD, and ATP

The energy released from the breakdown of the chemical bonds within nutrients can be stored either through the reduction of electron carriers or in the bonds of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In living systems, a small class of compounds functions as mobile electron carriers, molecules that bind to and shuttle high-energy electrons between compounds in pathways. The principal electron carriers we will consider originate from the B vitamin group and are derivatives of nucleotides; they are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphate, and flavin adenine dinucleotide. These compounds can be easily reduced or oxidized. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+/NADH) is the most common mobile electron carrier used in catabolism. NAD+ is the oxidized form of the molecule; NADH is the reduced form of the molecule. Nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), the oxidized form of an NAD+ variant that contains an extra phosphate group, is another important electron carrier; it forms NADPH when reduced. The oxidized form of flavin adenine dinucleotide is FAD, and its reduced form is FADH2. Both NAD+/NADH and FAD/FADH2 are extensively used in energy extraction from sugars during catabolism in chemoheterotrophs, whereas NADP+/NADPH plays an important role in anabolic reactions and photosynthesis. Collectively, FADH2, NADH, and NADPH are often referred to as having reducing power due to their ability to donate electrons to various chemical reactions.

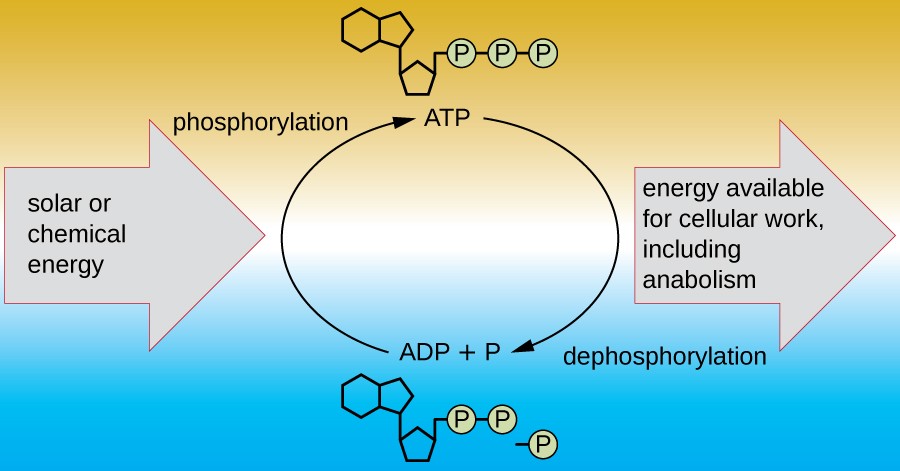

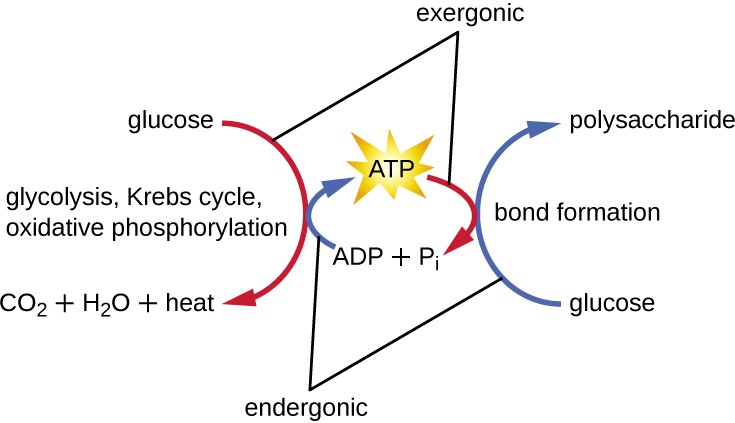

A living cell must be able to handle the energy released during catabolism in a way that enables the cell to store energy safely and release it for use only as needed. Living cells accomplish this by using the compound adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is often called the “energy currency” of the cell, and, like currency, this versatile compound can be used to fill any energy need of the cell. At the heart of ATP is a molecule of adenosine monophosphate (AMP), which is composed of an adenine molecule bonded to a ribose molecule and a single phosphate group. Ribose is a five-carbon sugar found in RNA, and AMP is one of the nucleotides in RNA. The addition of a second phosphate group to this core molecule results in the formation of adenosine diphosphate (ADP); the addition of a third phosphate group forms ATP (Figure 8.3). Adding a phosphate group to a molecule, a process called phosphorylation, requires energy. Phosphate groups are negatively charged and thus repel one another when they are arranged in series, as they are in ADP and ATP. This repulsion makes the ADP and ATP molecules inherently unstable. Thus, the bonds between phosphate groups (one in ADP and two in ATP) are called high-energy phosphate bonds. When these high- energy bonds are broken to release one phosphate (called inorganic phosphate [Pi]) or two connected phosphate groups (called pyrophosphate [PPi]) from ATP through a process called dephosphorylation, energy is released to drive endergonic reactions (Figure 8.4).

Check Your Understanding

- What is the function of an electron carrier?

Enzyme Structure and Function

A substance that helps speed up a chemical reaction is a catalyst. Catalysts are not used or changed during chemical reactions and, therefore, are reusable. Whereas inorganic molecules may serve as catalysts for a wide range of chemical reactions, proteins called enzymes serve as catalysts for biochemical reactions inside cells. Enzymes thus play an important role in controlling cellular metabolism.

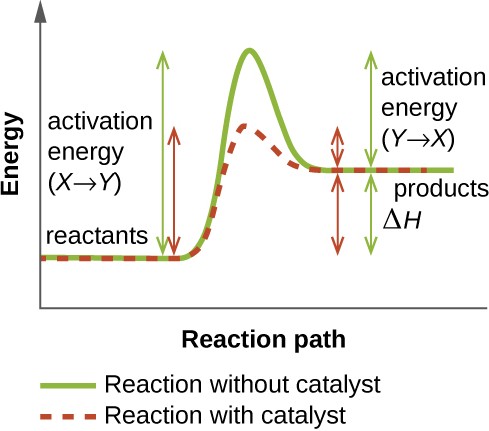

An enzyme functions by lowering the activation energy of a chemical reaction inside the cell. Activation energy is the energy needed to form or break chemical bonds and convert reactants to products (Figure 8.5). Enzymes lower the activation energy by binding to the reactant molecules and holding them in such a way as to speed up the reaction.

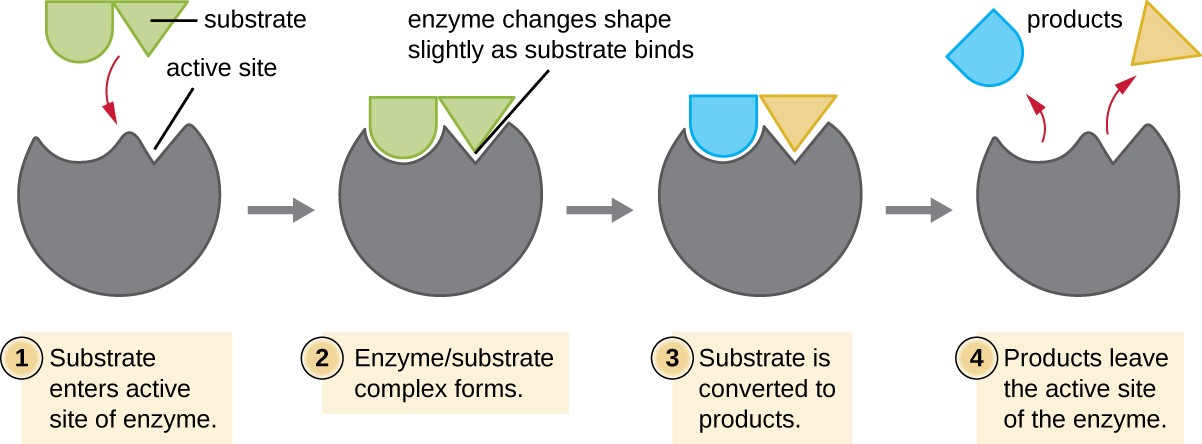

The chemical reactants to which an enzyme binds are called substrates, and the location within the enzyme where the substrate binds is called the enzyme’s active site. The characteristics of the amino acids near the active site create a very specific chemical environment within the active site that induces suitability to binding, albeit briefly, to a specific substrate (or substrates). Due to this jigsaw puzzle-like match between an enzyme and its substrates, enzymes are known for their specificity. In fact, as an enzyme binds to its substrate(s), the enzyme structure changes slightly to find the best fit between the transition state (a structural intermediate between the substrate and product) and the active site, just as a rubber glove molds to a hand inserted into it. This active-site modification in the presence of substrate, along with the simultaneous formation of the transition state, is called induced fit (Figure 8.6). Overall, there is a specifically matched enzyme for each substrate and, thus, for each chemical reaction; however, there is some flexibility as well. Some enzymes have the ability to act on several different structurally related substrates.

Step 1: Substrate enters active site of enzyme. Step 2: Enzyme/substrate complex forms. Enzyme changes shape slightly as substrate binds. Step 3: Substrate is converted to products. Step 4: Products leave the active site of the enzyme.

Enzymes are subject to influences by local environmental conditions such as pH, substrate concentration, and temperature. Although increasing the environmental temperature generally increases reaction rates, enzyme catalyzed or otherwise, increasing or decreasing the temperature outside of an optimal range can affect chemical bonds within the active site, making them less well suited to bind substrates. High temperatures will eventually cause enzymes, like other biological molecules, to denature, losing their three-dimensional structure and function. Enzymes are also suited to function best within a certain pH range, and, as with temperature, extreme environmental pH values (acidic or basic) can cause enzymes to denature. Active-site amino-acid side chains have their own acidic or basic properties that are optimal for catalysis and, therefore, are sensitive to changes in pH.

Another factor that influences enzyme activity is substrate concentration: Enzyme activity is increased at higher concentrations of substrate until it reaches a saturation point at which the enzyme can bind no additional substrate. Overall, enzymes are optimized to work best under the environmental conditions in which the organisms that produce them live. For example, while microbes that inhabit hot springs have enzymes that work best at high temperatures, human pathogens have enzymes that work best at 37°C. Similarly, while enzymes produced by most organisms work best at a neutral pH, microbes growing in acidic environments make enzymes optimized to low pH conditions, allowing for their growth at those conditions.

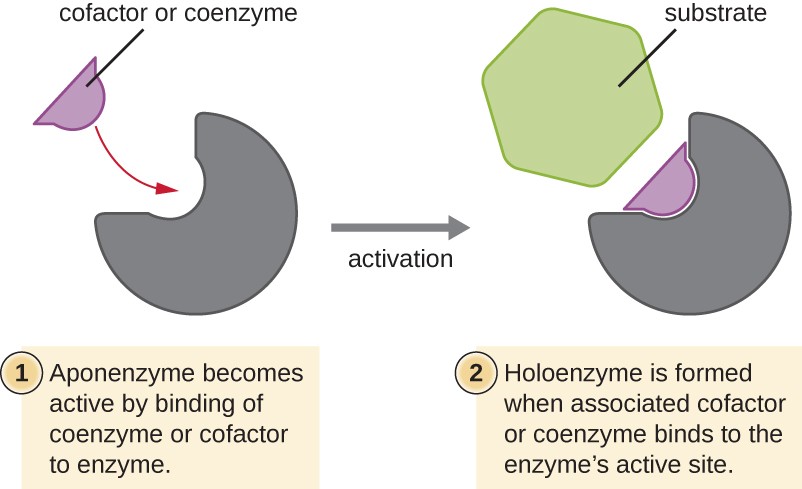

Many enzymes do not work optimally, or even at all, unless bound to other specific nonprotein helper molecules, either temporarily through ionic or hydrogen bonds or permanently through stronger covalent bonds. Binding to these molecules promotes optimal conformation and function for their respective enzymes. Two types of helper molecules are cofactors and coenzymes. Cofactors are inorganic ions such as iron (Fe2+) and magnesium (Mg2+) that help stabilize enzyme conformation and function. One example of an enzyme that requires a metal ion as a cofactor is the enzyme that builds DNA molecules, DNA polymerase, which requires a bound zinc ion (Zn2+) to function.

Coenzymes are organic helper molecules that are required for enzyme action. Like enzymes, they are not consumed and, hence, are reusable. The most common sources of coenzymes are dietary vitamins. Some vitamins are precursors to coenzymes and others act directly as coenzymes.

Some cofactors and coenzymes, like coenzyme A (CoA), often bind to the enzyme’s active site, aiding in the chemistry of the transition of a substrate to a product (Figure 8.7). In such cases, an enzyme lacking a necessary cofactor or coenzyme is called an apoenzyme and is inactive. Conversely, an enzyme with the necessary associated cofactor or coenzyme is called a holoenzyme and is active. NADH and ATP are also both examples of commonly used coenzymes that provide high-energy electrons or phosphate groups, respectively, which bind to enzymes, thereby activating them.

Step 1: Aponenzyme becomes active by binding of coenzyme or cofactor to enzyme. Step 2: Holoenzyme is formed when associated cofactor or coenzyme binds to the enzyme’s active site.

Check Your Understanding

- What role do enzymes play in a chemical reaction?

Enzyme Inhibitors

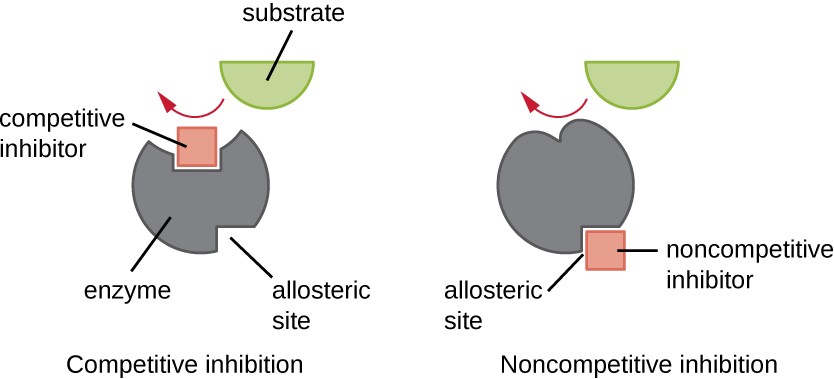

Enzymes can be regulated in ways that either promote or reduce their activity. There are many different kinds of molecules that inhibit or promote enzyme function, and various mechanisms exist for doing so (Figure 8.8). A competitive inhibitor is a molecule similar enough to a substrate that it can compete with the substrate for binding to

the active site by simply blocking the substrate from binding. For a competitive inhibitor to be effective, the inhibitor concentration needs to be approximately equal to the substrate concentration. Sulfa drugs provide a good example of competitive competition. They are used to treat bacterial infections because they bind to the active site of an enzyme within the bacterial folic acid synthesis pathway. When present in a sufficient dose, a sulfa drug prevents folic acid synthesis, and bacteria are unable to grow because they cannot synthesize DNA, RNA, and proteins. Humans are unaffected because we obtain folic acid from our diets.

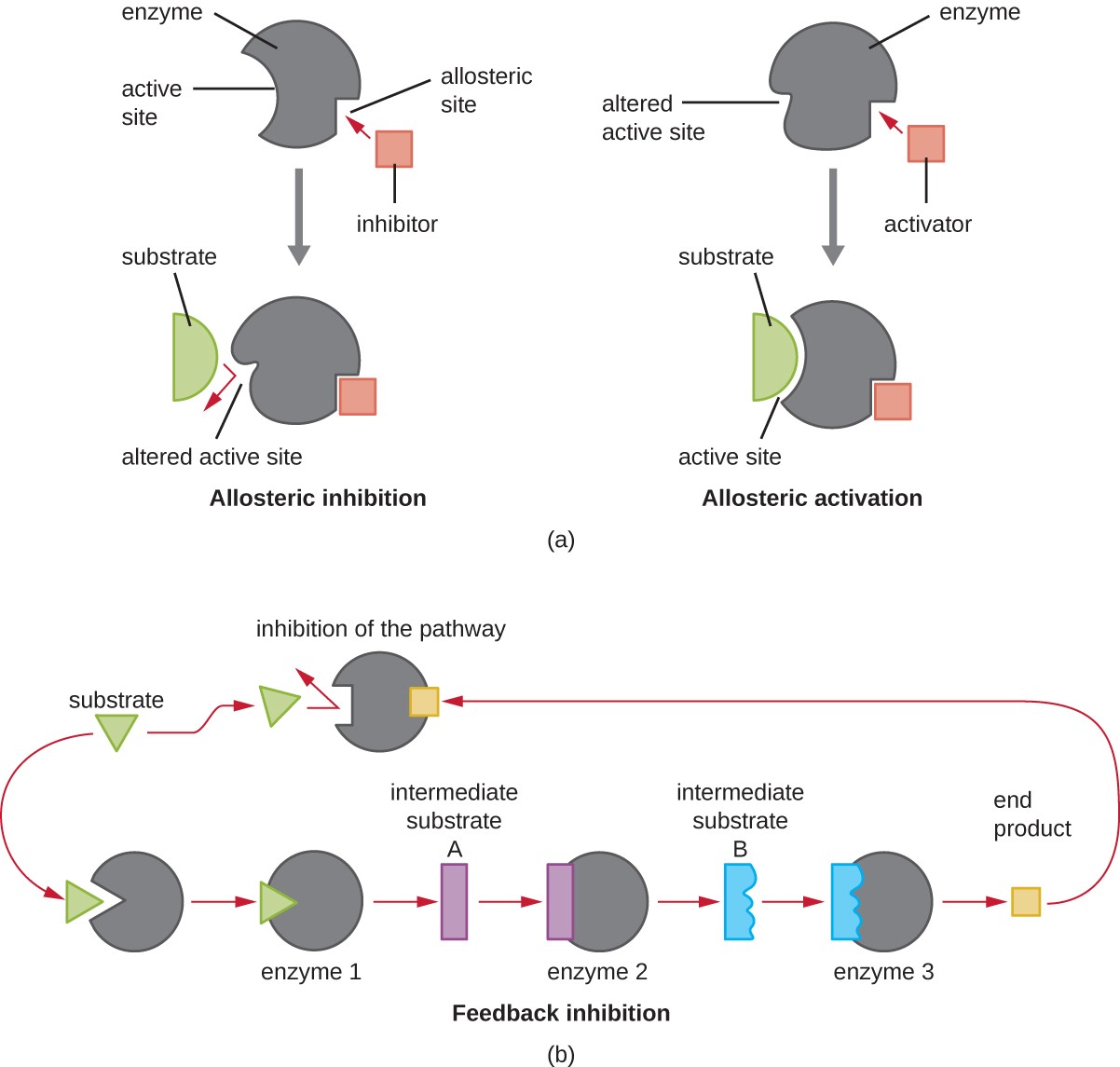

On the other hand, a noncompetitive (allosteric) inhibitor binds to the enzyme at an allosteric site, a location other than the active site, and still manages to block substrate binding to the active site by inducing a conformational change that reduces the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate (Figure 8.9). Because only one inhibitor molecule is needed per enzyme for effective inhibition, the concentration of inhibitors needed for noncompetitive inhibition is typically much lower than the substrate concentration.

In addition to allosteric inhibitors, there are allosteric activators that bind to locations on an enzyme away from the active site, inducing a conformational change that increases the affinity of the enzyme’s active site(s) for its substrate(s).

Allosteric control is an important mechanism of regulation of metabolic pathways involved in both catabolism and anabolism. In a most efficient and elegant way, cells have evolved also to use the products of their own metabolic reactions for feedback inhibition of enzyme activity. Feedback inhibition involves the use of a pathway product to regulate its own further production. The cell responds to the abundance of specific products by slowing production during anabolic or catabolic reactions (Figure 8.9).

Check Your Understanding

- Explain the difference between a competitive inhibitor and a noncompetitive inhibitor.