14.2 – Fundamentals of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy

Learning Objectives

- Contrast bacteriostatic versus bactericidal antibacterial activities

- Contrast broad-spectrum drugs versus narrow-spectrum drugs

- Explain the significance of superinfections

- Discuss the significance of dosage and the route of administration of a drug

- Identify factors and variables that can influence the side effects of a drug

- Describe the significance of positive and negative interactions between drugs

Several factors are important in choosing the most appropriate antimicrobial drug therapy, including bacteriostatic versus bactericidal mechanisms, spectrum of activity, dosage and route of administration, the potential for side effects, and the potential interactions between drugs. The following discussion will focus primarily on antibacterial drugs, but the concepts translate to other antimicrobial classes.

Bacteriostatic Versus Bactericidal

Antibacterial drugs can be either bacteriostatic or bactericidal in their interactions with target bacteria. Bacteriostatic drugs cause a reversible inhibition of growth, with bacterial growth restarting after elimination of the drug. By contrast, bactericidal drugs kill their target bacteria. The decision of whether to use a bacteriostatic or bactericidal drugs depends on the type of infection and the immune status of the patient. In a patient with strong immune defenses, bacteriostatic and bactericidal drugs can be effective in achieving clinical cure. However, when a patient is immunocompromised, a bactericidal drug is essential for the successful treatment of infections. Regardless of the immune status of the patient, life-threatening infections such as acute endocarditis require the use of a bactericidal drug.

Spectrum of Activity

The spectrum of activity of an antibacterial drug relates to diversity of targeted bacteria. A narrow-spectrum antimicrobial targets only specific subsets of bacterial pathogens. For example, some narrow-spectrum drugs only target gram-positive bacteria, whereas others target only gram-negative bacteria. If the pathogen causing an infection has been identified, it is best to use a narrow-spectrum antimicrobial and minimize collateral damage to the normal microbiota. A broad-spectrum antimicrobial targets a wide variety of bacterial pathogens, including both gram- positive and gram-negative species, and is frequently used as empiric therapy to cover a wide range of potential pathogens while waiting on the laboratory identification of the infecting pathogen. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials are also used for polymicrobic infections (mixed infection with multiple bacterial species), or as prophylactic prevention of infections with surgery/invasive procedures. Finally, broad-spectrum antimicrobials may be selected to treat an infection when a narrow-spectrum drug fails because of development of drug resistance by the target pathogen.

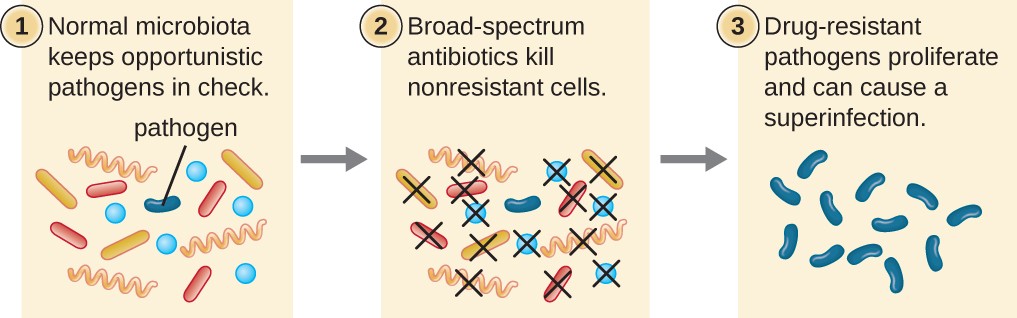

The risk associated with using broad-spectrum antimicrobials is that they will also target a broad spectrum of the normal microbiota, increasing the risk of a superinfection, a secondary infection in a patient having a preexisting infection. A superinfection develops when the antibacterial intended for the preexisting infection kills the protective microbiota, allowing another pathogen resistant to the antibacterial to proliferate and cause a secondary infection (Figure 14.6). Common examples of superinfections that develop as a result of antimicrobial usage include yeast infections (candidiasis) and pseudomembranous colitis caused by Clostridium difficile, which can be fatal.

Diagram of process of superinfection. 1: Normal microbiota keeps opportunistic pathogens in check. Image shows many different bacteria, only 1 of which is labeled pathogen. 2: Broad-spectrum antibiotics kill nonresistant cells. Image shows all cells but pathogen being killed. 3: Drug-resistant pathogens proliferate and can cause a superinfection. Image shows many of the pathogen.

Check Your Understanding

- What is a superinfection and how does one arise?

Dosage and Route of Administration

The amount of medication given during a certain time interval is the dosage, and it must be determined carefully to ensure that optimum therapeutic drug levels are achieved at the site of infection without causing significant toxicity (side effects) to the patient. Each drug class is associated with a variety of potential side effects, and some of these are described for specific drugs later in this chapter. Despite best efforts to optimize dosing, allergic reactions and other potentially serious side effects do occur. Therefore, the goal is to select the optimum dosage that will minimize

the risk of side effects while still achieving clinical cure, and there are important factors to consider when selecting the best dose and dosage interval. For example, in children, dose is based upon the patient’s mass. However, the same is not true for adults and children 12 years of age and older, for which there is typically a single standard dose regardless of the patient’s mass. With the great variability in adult body mass, some experts have argued that mass should be considered for all patients when determining appropriate dosage.[1] An additional consideration is how drugs are metabolized and eliminated from the body. In general, patients with a history of liver or kidney dysfunction may experience reduced drug metabolism or clearance from the body, resulting in increased drug levels that may lead to toxicity and make them more prone to side effects.

There are also some factors specific to the drugs themselves that influence appropriate dose and time interval between doses. For example, the half-life, or rate at which 50% of a drug is eliminated from the plasma, can vary significantly between drugs. Some drugs have a short half-life of only 1 hour and must be given multiple times a day, whereas other drugs have half-lives exceeding 12 hours and can be given as a single dose every 24 hours. Although a longer half-life can be considered an advantage for an antibacterial when it comes to convenient dosing intervals, the longer half-life can also be a concern for a drug that has serious side effects because drug levels may remain toxic for a longer time. Last, some drugs are dose dependent, meaning they are more effective when administered in large doses to provide high levels for a short time at the site of infection. Others are time dependent, meaning they are more effective when lower optimum levels are maintained over a longer period of time.

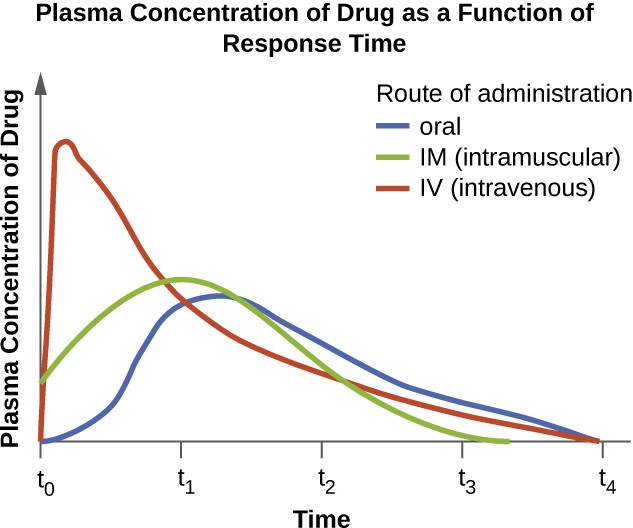

The route of administration, the method used to introduce a drug into the body, is also an important consideration for drug therapy. Drugs that can be administered orally are generally preferred because patients can more conveniently take these drugs at home. However, some drugs are not absorbed easily from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract into the bloodstream. These drugs are often useful for treating diseases of the intestinal tract, such as tapeworms treated with niclosamide, or for decontaminating the bowel, as with colistin. Some drugs that are not absorbed easily, such as bacitracin, polymyxin, and several antifungals, are available as topical preparations for treatment of superficial skin infections. Sometimes, patients may not initially be able to take oral medications because of their illness (e.g., vomiting, intubation for respirator). When this occurs, and when a chosen drug is not absorbed in the GI tract, administration of the drug by a parenteral route (intravenous or intramuscular injection) is preferred and typically is performed in health-care settings. For most drugs, the plasma levels achieved by intravenous administration is substantially higher than levels achieved by oral or intramuscular administration, and this can also be an important consideration when choosing the route of administration for treating an infection ( Figure 14.7).

Graph with time on the X axis and Plasma Concentration of Drug on the Y axis. IV route increases plasma concentration very quickly and then tapes off. Intramuscular rout and oral route increase concentrations more slowly with the intramuscular route being a bit faster than oral but also dropping off more quickly.

Check Your Understanding

- List five factors to consider when determining the dosage of a drug.

- Name some typical side effects associated with drugs and identify some factors that might contribute to these side effects.

Drug Interactions

For the optimum treatment of some infections, two antibacterial drugs may be administered together to provide a synergistic interaction that is better than the efficacy of either drug alone. A classic example of synergistic combinations is trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). Individually, these two drugs provide only bacteriostatic inhibition of bacterial growth, but combined, the drugs are bactericidal.

Whereas synergistic drug interactions provide a benefit to the patient, antagonistic interactions produce harmful effects. Antagonism can occur between two antimicrobials or between antimicrobials and nonantimicrobials being used to treat other conditions. The effects vary depending on the drugs involved, but antagonistic interactions may cause loss of drug activity, decreased therapeutic levels due to increased metabolism and elimination, or increased potential for toxicity due to decreased metabolism and elimination. As an example, some antibacterials are absorbed most effectively from the acidic environment of the stomach. If a patient takes antacids, however, this increases the pH of the stomach and negatively impacts the absorption of these antimicrobials, decreasing their effectiveness in treating an infection. Studies have also shown an association between use of some antimicrobials and failure of oral contraceptives.[2]

Check Your Understanding

- Explain the difference between synergistic and antagonistic drug interactions.

Eye on Ethics

Resistance Police

In the United States and many other countries, most antimicrobial drugs are self-administered by patients at home. Unfortunately, many patients stop taking antimicrobials once their symptoms dissipate and they feel better. If a 10-day course of treatment is prescribed, many patients only take the drug for 5 or 6 days, unaware of the negative consequences of not completing the full course of treatment. A shorter course of treatment not only fails to kill the target organisms to expected levels, it also selects for drug-resistant variants within the target population and within the patient’s microbiota.

Patients’ nonadherence especially amplifies drug resistance when the recommended course of treatment is long. Treatment for tuberculosis (TB) is a case in point, with the recommended treatment lasting from 6 months to a year. The CDC estimates that about one-third of the world’s population is infected with TB, most living in underdeveloped or underserved regions where antimicrobial drugs are available over the counter. In such countries, there may be even lower rates of adherence than in developed areas. Nonadherence leads to antibiotic resistance and more difficulty in controlling pathogens. As a direct result, the emergence of multidrug- resistant and extensively drug-resistant strains of TB is becoming a huge problem.

Overprescription of antimicrobials also contributes to antibiotic resistance. Patients often demand antibiotics for diseases that do not require them, like viral colds and ear infections. Pharmaceutical companies aggressively market drugs to physicians and clinics, making it easy for them to give free samples to patients, and some pharmacies even offer certain antibiotics free to low-income patients with a prescription.

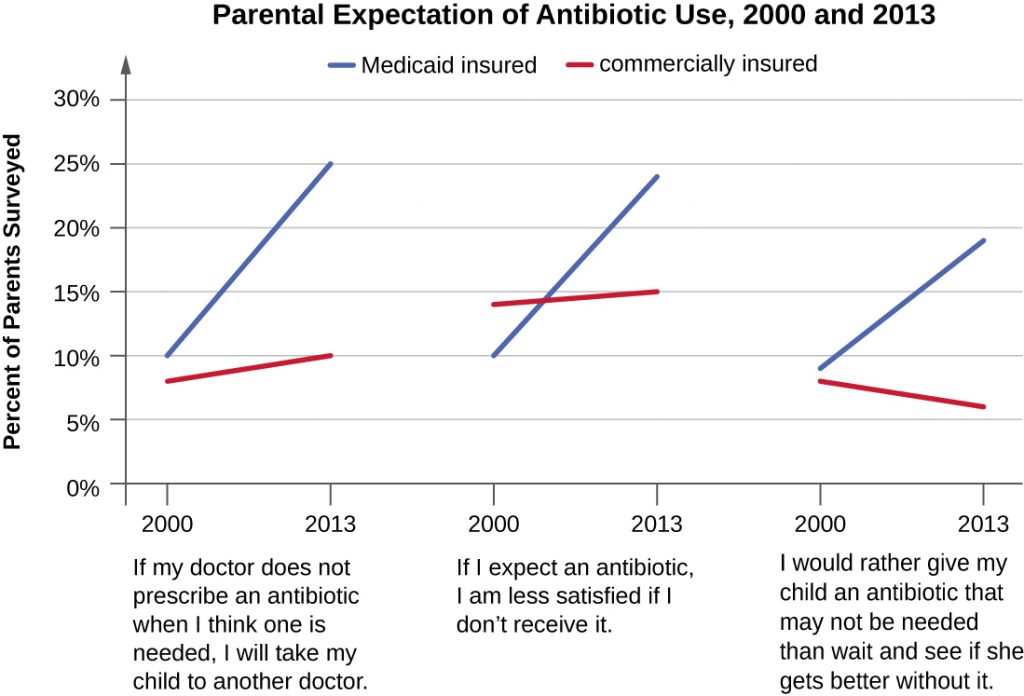

In recent years, various initiatives have aimed to educate parents and clinicians about the judicious use of antibiotics. However, a recent study showed that, between 2000 and 2013, the parental expectation for antimicrobial prescriptions for children actually increased (Figure 14.8).

One possible solution is a regimen called directly observed therapy (DOT), which involves the supervised administration of medications to patients. Patients are either required to visit a health-care facility to receive their medications, or health-care providers must administer medication in patients’ homes or another designated location. DOT has been implemented in many cases for the treatment of TB and has been shown to be effective; indeed, DOT is an integral part of WHO’s global strategy for eradicating TB.[3],[4] But is this a practical strategy for all antibiotics? Would patients taking penicillin, for example, be more or less likely to adhere to the full course of treatment if they had to travel to a health-care facility for each dose? And who would pay for the increased cost associated with DOT? When it comes to overprescription, should someone be policing physicians or drug companies to enforce best practices? What group should assume this responsibility, and what penalties would be effective in discouraging overprescription?

hree graphs showing changes in perception from 2000 to 2013. If my doctor does not prescribe an antibiotic when I think one is needed, I will take my child to another doctor. Medicaid insured insured (2000, 10%) and (2013, 25%); commercially insured (2000, 8%) and (2013, 10%). If I expect an antibiotic, I am less satisfied if I don’t receive it: Medicaid insured (2000, 10%) and (2013, 24%); commercially insured (2000, 14%) and (2013, 15%). If would rather give my child an antibiotic that may not be needed than wait to see if she gets better without it.. Medicaid insured (2000, 9%) and (2013, 19%). Commercially insured (2000, 8%) and (2013, 6%)

Footnotes

M.E. Falagas, D.E. Karageorgopoulos. “Adjustment of Dosing of Antimicrobial Agents for Bodyweight in Adults.” The Lancet 375 no. 9710 (2010):248–251.

B.D. Dickinson et al. “Drug Interactions between Oral Contraceptives and Antibiotics.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 98, no. 5 (2001):853–860.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Tuberculosis (TB).” http://www.cdc.gov/tb/education/ssmodules/module9/ss9reading2.htm. Accessed June 2, 2016.

World Health Organization. “Tuberculosis (TB): The Five Elements of DOTS.” http://www.who.int/tb/dots/whatisdots/en/. Accessed June 2, 2016.

Vaz, L.E., et al. “Prevalence of Parental Misconceptions About Antibiotic Use.” Pediatrics 136 no.2 (August 2015). DOI: 10.1542/ peds.2015-0883.