4.4 – Gram-Positive Bacteria

Learning Objectives

- Describe the unique features of each category of high G+C and low G+C gram-positive bacteria

- Identify similarities and differences between high G+C and low G+C bacterial groups

- Give an example of a bacterium of high G+C and low G+C group commonly associated with each category

Prokaryotes are identified as gram-positive if they have a multiple layer matrix of peptidoglycan forming the cell wall. Crystal violet, the primary stain of the Gram stain procedure, is readily retained and stabilized within this matrix, causing gram-positive prokaryotes to appear purple under a brightfield microscope after Gram staining. For many years, the retention of Gram stain was one of the main criteria used to classify prokaryotes, even though some prokaryotes did not readily stain with either the primary or secondary stains used in the Gram stain procedure.

Advances in nucleic acid biochemistry have revealed additional characteristics that can be used to classify gram-positive prokaryotes, namely the guanine to cytosine ratios (G+C) in DNA and the composition of 16S rRNA subunits. Microbiologists currently recognize two distinct groups of gram-positive, or weakly staining gram-positive, prokaryotes. The class Actinobacteria comprises the high G+C gram-positive bacteria, which have more than 50% guanine and cytosine nucleotides in their DNA. The class Bacilli comprises low G+C gram-positive bacteria, which have less than 50% of guanine and cytosine nucleotides in their DNA.

The name Actinobacteria comes from the Greek words for rays and small rod, but Actinobacteria are very diverse. Their microscopic appearance can range from thin filamentous branching rods to coccobacilli. Some Actinobacteria are very large and complex, whereas others are among the smallest independently living organisms. Most Actinobacteria live in the soil, but some are aquatic. The vast majority are aerobic. One distinctive feature of this group is the presence of several different peptidoglycans in the cell wall.

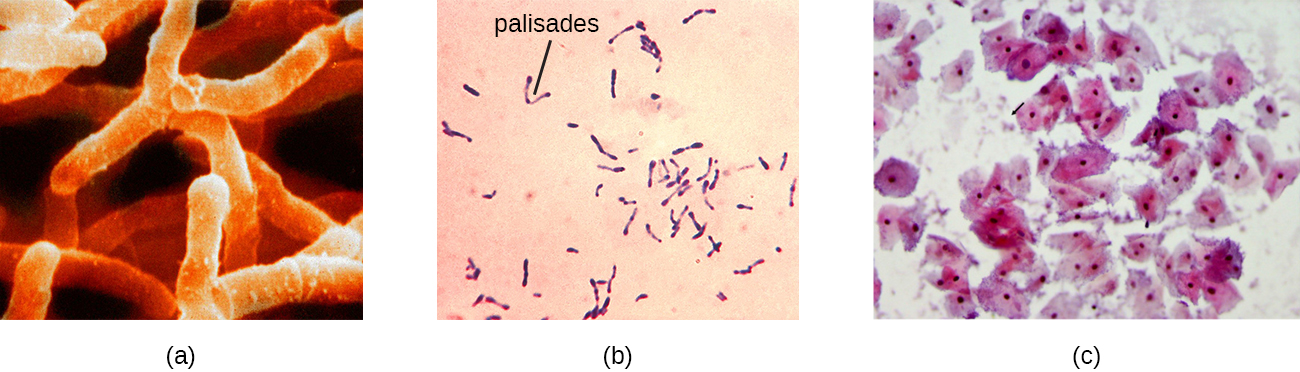

The genus Actinomyces is a much studied representative of Actinobacteria. Actinomyces spp. play an important role in soil ecology, and some species are human pathogens. A number of Actinomyces spp. inhabit the human mouth and are opportunistic pathogens, causing infectious diseases like periodontitis (inflammation of the gums) and oral abscesses. The species A. israelii is an anaerobe notorious for causing endocarditis (inflammation of the inner lining of the heart) (Figure 4.18).

The genus Mycobacterium is represented by bacilli covered with a mycolic acid coat. This waxy coat protects the bacteria from some antibiotics, prevents them from drying out, and blocks penetration by Gram stain reagents (see Staining Microscopic Specimens). Because of this, a special acid-fast staining procedure is used to visualize these bacteria. The genus Mycobacterium is an important cause of a diverse group of infectious diseases. M. tuberculosis is the causative agent of tuberculosis, a disease that primarily impacts the lungs but can infect other parts of the body as well. It has been estimated that one-third of the world’s population has been infected with M. tuberculosis and millions of new infections occur each year. Treatment of M. tuberculosis is challenging and requires patients to take a combination of drugs for an extended time. Complicating treatment even further is the development and spread of multidrug-resistant strains of this pathogen.

Another pathogenic species, M. leprae, is the cause of Hansen’s disease (leprosy), a chronic disease that impacts peripheral nerves and the integrity of the skin and mucosal surface of the respiratory tract. Loss of pain sensation and the presence of skin lesions increase susceptibility to secondary injuries and infections with other pathogens.

Bacteria in the genus Corynebacterium contain diaminopimelic acid in their cell walls, and microscopically often form palisades, or pairs of rod-shaped cells resembling the letter V. Cells may contain metachromatic granules, intracellular storage of inorganic phosphates that are useful for identification of Corynebacterium. The vast majority of Corynebacterium spp. are nonpathogenic; however, C. diphtheria is the causative agent of diphtheria, a disease that can be fatal, especially in children (Figure 4.18). C. diphtheria produces a toxin that forms a pseudomembrane in the patient’s throat, causing swelling, difficulty breathing, and other symptoms that can become serious if untreated.

The genus Bifidobacterium consists of filamentous anaerobes, many of which are commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract, vagina, and mouth. In fact, Bifidobacterium spp. constitute a substantial part of the human gut microbiota and are frequently used as probiotics and in yogurt production.

The genus Gardnerella, contains only one species, G. vaginalis. This species is defined as “gram-variable” because its small coccobacilli do not show consistent results when Gram stained (Figure 4.18). Based on its genome, it is placed into the high G+C gram-positive group. G. vaginalis can cause bacterial vaginosis in women; symptoms are typically mild or even undetectable, but can lead to complications during pregnancy.

Actinobacteria: High G+C Gram-Positive

| Example Genus | Microscopic Morphology | Unique Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Actinomyces | Gram-positive bacillus; in colonies, shows fungus-like threads (hyphae) | Facultative anaerobes; in soil, decompose organic matter; in the human mouth, may cause gum disease |

| Arthrobacter | Gram-positive bacillus (at the exponential stage of growth) or coccus (in stationary phase) | Obligate aerobes; divide by “snapping,” forming V-like pairs of daughter cells; degrade phenol, can be used in bioremediation |

| Bifidobacterium | Gram-positive, filamentous actinobacterium | Anaerobes commonly found in human gut microbiota |

| Corynebacterium | Gram-positive bacillus | Aerobes or facultative anaerobes; form palisades; grow slowly; require enriched media in culture; C. diphtheriae causes diphtheria |

| Frankia | Gram-positive, fungus-like (filamentous) bacillus | Nitrogen-fixing bacteria; live in symbiosis with legumes |

| Gardnerella | Gram-variable coccobacillus | Colonize the human vagina, may alter the microbial ecology, thus leading to vaginosis |

| Micrococcus | Gram-positive coccus, form microscopic clusters | Ubiquitous in the environment and on the human skin; oxidase-positive (as opposed to morphologically similar S. aureus); some are opportunistic pathogens |

| Mycobacterium | Gram-positive, acid-fast bacillus | Slow growing, aerobic, resistant to drying and phagocytosis; covered with a waxy coat made of mycolic acid; M. tuberculosis causes tuberculosis; M. leprae causes leprosy |

| Nocardia | Weakly gram-positive bacillus; forms acid-fast branches | May colonize the human gingiva; may cause severe pneumonia and inflammation of the skin |

| Propionibacterium | Gram-positive bacillus | Aerotolerant anaerobe; slow-growing; P. acnes reproduces in the human sebaceous glands and may cause or contribute to acne |

| Rhodococcus | Gram-positive bacillus | Strict aerobe; used in industry for biodegradation of pollutants; R. fascians is a plant pathogen, and R. equi causes pneumonia in foals |

| Streptomyces | Gram-positive, fungus-like (filamentous) bacillus | Very diverse genus (>500 species); aerobic, spore-forming bacteria; scavengers, decomposers found in soil (give the soil its “earthy” odor); used in pharmaceutical industry as antibiotic producers (more than two-thirds of clinically useful antibiotics) |

Check Your Understanding

- What is one distinctive feature of Actinobacteria?

Low G + C Grab-positive Bacteria

The low G+C gram-positive bacteria have less than 50% guanine and cytosine in their DNA, and this group of bacteria includes a number of genera of bacteria that are pathogenic.

Clostridia

One large and diverse class of low G+C gram-positive bacteria is Clostridia. The best studied genus of this class is Clostridium. These rod-shaped bacteria are generally obligate anaerobes that produce endospores and can be found in anaerobic habitats like soil and aquatic sediments rich in organic nutrients. The endospores may survive for many years.

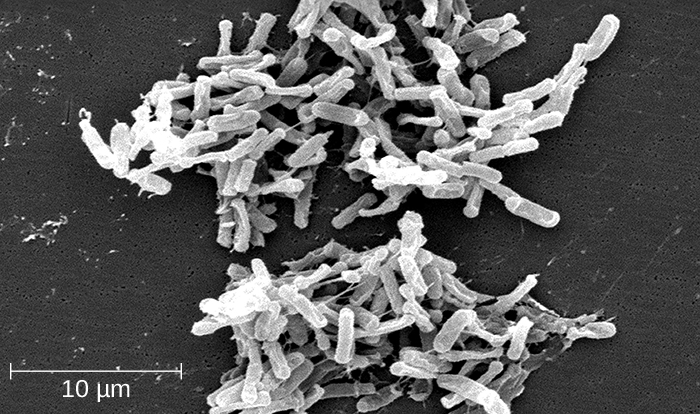

Clostridium spp. produce more kinds of protein toxins than any other bacterial genus, and several species are human pathogens. C. perfringens is the third most common cause of food poisoning in the United States and is the causative agent of an even more serious disease called gas gangrene. Gas gangrene occurs when C. perfringens endospores enter a wound and germinate, becoming viable bacterial cells and producing a toxin that can cause the necrosis (death) of tissue. C. tetani, which causes tetanus, produces a neurotoxin that is able to enter neurons, travel to regions of the central nervous system where it blocks the inhibition of nerve impulses involved in muscle contractions, and cause a life-threatening spastic paralysis. C. botulinum produces botulinum neurotoxin, the most lethal biological toxin known. Botulinum toxin is responsible for rare but frequently fatal cases of botulism. The toxin blocks the release of acetylcholine in neuromuscular junctions, causing flaccid paralysis. In very small concentrations, botulinum toxin has been used to treat muscle pathologies in humans and in a cosmetic procedure to eliminate wrinkles. C. difficile is a common source of hospital-acquired infections (Figure 4.19) that can result in serious and even fatal cases of colitis (inflammation of the large intestine). Infections often occur in patients who are immunosuppressed or undergoing antibiotic therapy that alters the normal microbiota of the gastrointestinal tract. Appendix D lists the genera, species, and related diseases for Clostridia.

Lactobacillales

The order Lactobacillales comprises low G+C gram-positive bacteria that include both bacilli and cocci in the genera Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus. Bacteria of the latter three genera typically are spherical or ovoid and often form chains.

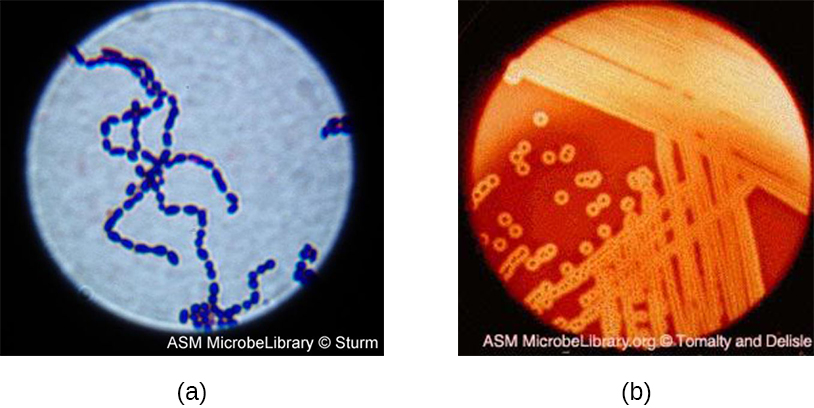

Streptococcus, the name of which comes from the Greek word for twisted chain, is responsible for many types of infectious diseases in humans. Species from this genus, often referred to as streptococci, are usually classified by serotypes called Lancefield groups, and by their ability to lyse red blood cells when grown on blood agar.

S. pyogenes belongs to the Lancefield group A, β-hemolytic Streptococcus. This species is considered a pyogenic pathogen because of the associated pus production observed with infections it causes (Figure 4.20). S. pyogenes is the most common cause of bacterial pharyngitis (strep throat); it is also an important cause of various skin infections that can be relatively mild (e.g., impetigo) or life threatening (e.g., necrotizing fasciitis, also known as flesh eating disease), life threatening.

The nonpyogenic (i.e., not associated with pus production) streptococci are a group of streptococcal species that are not a taxon but are grouped together because they inhabit the human mouth. The nonpyogenic streptococci do not belong to any of the Lancefield groups. Most are commensals, but a few, such as S. mutans, are implicated in the development of dental caries.

S. pneumoniae (commonly referred to as pneumococcus), is a Streptococcus species that also does not belong to any Lancefield group. S. pneumoniae cells appear microscopically as diplococci, pairs of cells, rather than the long chains typical of most streptococci. Scientists have known since the 19th century that S. pneumoniae causes pneumonia and other respiratory infections. However, this bacterium can also cause a wide range of other diseases, including meningitis, septicemia, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis, especially in newborns, the elderly, and patients with immunodeficiency.

Bacilli

The name of the class Bacilli suggests that it is made up of bacteria that are bacillus in shape, but it is a morphologically diverse class that includes bacillus-shaped and cocccus-shaped genera. Among the many genera in this class are two that are very important clinically: Bacillus and Staphylococcus.

Bacteria in the genus Bacillus are bacillus in shape and can produce endospores. They include aerobes or facultative anaerobes. A number of Bacillus spp. are used in various industries, including the production of antibiotics (e.g., barnase), enzymes (e.g., alpha-amylase, BamH1 restriction endonuclease), and detergents (e.g., subtilisin).

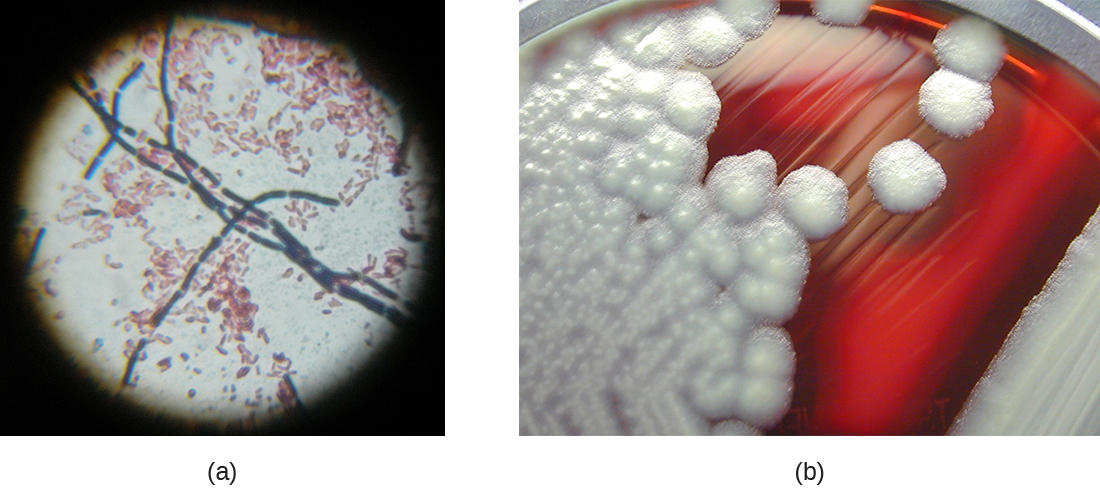

Two notable pathogens belong to the genus Bacillus. B. anthracis is the pathogen that causes anthrax, a severe disease that affects wild and domesticated animals and can spread from infected animals to humans. Anthrax manifests in humans as charcoal-black ulcers on the skin, severe enterocolitis, pneumonia, and brain damage due to swelling. If untreated, anthrax is lethal. B. cereus, a closely related species, is a pathogen that may cause food poisoning. It is a rod-shaped species that forms chains. Colonies appear milky white with irregular shapes when cultured on blood agar (Figure 4.21). One other important species is B. thuringiensis. This bacterium produces a number of substances used as insecticides because they are toxic for insects.

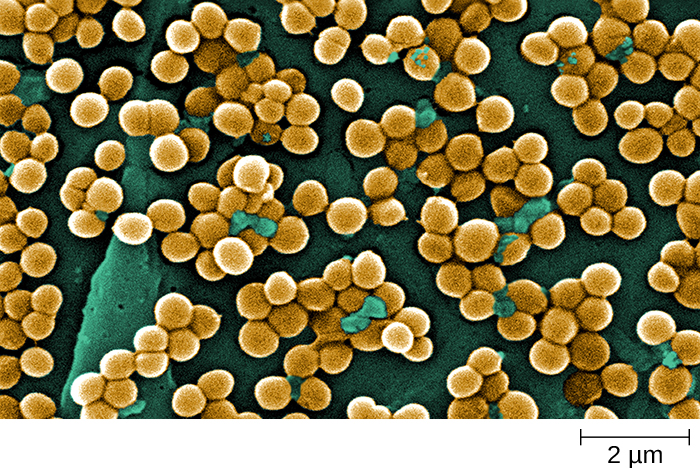

The genus Staphylococcus also belongs to the class Bacilli, even though its shape is coccus rather than a bacillus. The name Staphylococcus comes from a Greek word for bunches of grapes, which describes their microscopic appearance in culture (Figure 4.22). Staphylococcus spp. are facultative anaerobic, halophilic, and nonmotile. The two best-studied species of this genus are S. epidermidis and S. aureus.

S. epidermidis, whose main habitat is the human skin, is thought to be nonpathogenic for humans with healthy immune systems, but in patients with immunodeficiency, it may cause infections in skin wounds and prostheses (e.g., artificial joints, heart valves). S. epidermidis is also an important cause of infections associated with intravenous catheters. This makes it a dangerous pathogen in hospital settings, where many patients may be immunocompromised.

Strains of S. aureus cause a wide variety of infections in humans, including skin infections that produce boils, carbuncles, cellulitis, or impetigo. Certain strains of S. aureus produce a substance called enterotoxin, which can cause severe enteritis, often called staph food poisoning. Some strains of S. aureus produce the toxin responsible for toxic shock syndrome, which can result in cardiovascular collapse and death.

Many strains of S. aureus have developed resistance to antibiotics. Some antibiotic-resistant strains are designated as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA). These strains are some of the most difficult to treat because they exhibit resistance to nearly all available antibiotics, not just methicillin and vancomycin. Because they are difficult to treat with antibiotics, infections can be lethal. MRSA and VRSA are also contagious, posing a serious threat in hospitals, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, and other places where there are large populations of elderly, bedridden, and/or immunocompromised patients. Appendix D lists the genera, species, and related diseases for bacilli.

Mycoplasmas

Although Mycoplasma spp. do not possess a cell wall and, therefore, are not stained by Gram-stain reagents, this genus is still included with the low G+C gram-positive bacteria. The genus Mycoplasma includes more than 100 species, which share several unique characteristics. They are very small cells, some with a diameter of about 0.2 μm, which is smaller than some large viruses. They have no cell walls and, therefore, are pleomorphic, meaning that they may take on a variety of shapes and can even resemble very small animal cells. Because they lack a characteristic shape, they can be difficult to identify. One species, M. pneumoniae, causes the mild form of pneumonia known as “walking pneumonia” or “atypical pneumonia.” This form of pneumonia is typically less severe than forms caused by other bacteria or viruses.

Bacilli: Low G + C Gram-Positive Bacteria

| Example Genus | Microscopic Morphology | Unique Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus | Large, gram-positive bacillus | Aerobes or facultative anaerobes; form endospores; B. anthracis causes anthrax in cattle and humans, B. cereus may cause food poisoning |

| Clostridium | Gram-positive bacillus | Strict anaerobes; form endospores; all known species are pathogenic, causing tetanus, gas gangrene, botulism, and colitis |

| Enterococcus | Gram-positive coccus; forms microscopic pairs in culture (resembling Streptococcus pneumoniae) | Anaerobic aerotolerant bacteria, abundant in the human gut, may cause urinary tract and other infections in the nosocomial environment |

| Lactobacillus | Gram-positive bacillus | Facultative anaerobes; ferment sugars into lactic acid; part of the vaginal microbiota; used as probiotics |

| Leuconostoc | Gram-positive coccus; may form microscopic chains in culture | Fermenter, used in food industry to produce sauerkraut and kefir |

| Mycoplasma | The smallest bacteria; appear pleomorphic under electron microscope | Have no cell wall; classified as low G+C Gram-positive bacteria because of their genome; M. pneumoniae causes “walking” pneumonia |

| Staphylococcus | Gram-positive coccus; forms microscopic clusters in culture that resemble bunches of grapes | Tolerate high salt concentration; facultative anaerobes; produce catalase; S. aureus can also produce coagulase and toxins responsible for local (skin) and generalized infections |

| Streptococcus | Gram-positive coccus; forms chains or pairs in culture | Diverse genus; classified into groups based on sharing certain antigens; some species cause hemolysis and may produce toxins responsible for human local (throat) and generalized disease |

| Ureaplasma | Similar to Mycoplasma | Part of the human vaginal and lower urinary tract microbiota; may cause inflammation, sometimes leading to internal scarring and infertility |

Check Your Understanding

- Name some ways in which streptococci are classified.

- Name one pathogenic low G+C gram-positive bacterium and a disease it causes.

Eye on Ethics

Biopiracy and Bioprospecting

In 1969, an employee of a Swiss pharmaceutical company was vacationing in Norway and decided to collect some soil samples. He took them back to his lab, and the Swiss company subsequently used the fungus Tolypocladium inflatum in those samples to develop cyclosporine A, a drug widely used in patients who undergo tissue or organ transplantation. The Swiss company earns more than $1 billion a year for production of cyclosporine A, yet Norway receives nothing in return—no payment to the government or benefit for the Norwegian people. Despite the fact the cyclosporine A saves numerous lives, many consider the means by which the soil samples were obtained to be an act of “biopiracy,” essentially a form of theft. Do the ends justify the means in a case like this?

Nature is full of as-yet-undiscovered bacteria and other microorganisms that could one day be used to develop new life-saving drugs or treatments.21 Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies stand to reap huge profits from such discoveries, but ethical questions remain. To whom do biological resources belong? Should companies who invest (and risk) millions of dollars in research and development be required to share revenue or royalties for the right to access biological resources?

Compensation is not the only issue when it comes to bioprospecting. Some communities and cultures are philosophically opposed to bioprospecting, fearing unforeseen consequences of collecting genetic or biological material. Native Hawaiians, for example, are very protective of their unique biological resources.

For many years, it was unclear what rights government agencies, private corporations, and citizens had when it came to collecting samples of microorganisms from public land. Then, in 1993, the Convention on Biological Diversity granted each nation the rights to any genetic and biological material found on their own land. Scientists can no longer collect samples without a prior arrangement with the land owner for compensation. This convention now ensures that companies act ethically in obtaining the samples they use to create their products.

Footnotes

[21] J. Andre. Bioethics as Practice. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.