16.3 – Modes of Disease Transmission

Learning Objectives

- Describe the different types of disease reservoirs

- Compare contact, vector, and vehicle modes of transmission

- Identify important disease vectors

- Explain the prevalence of nosocomial infections

Understanding how infectious pathogens spread is critical to preventing infectious disease. Many pathogens require a living host to survive, while others may be able to persist in a dormant state outside of a living host. But having infected one host, all pathogens must also have a mechanism of transfer from one host to another or they will die when their host dies. Pathogens often have elaborate adaptations to exploit host biology, behavior, and ecology to live in and move between hosts. Hosts have evolved defenses against pathogens, but because their rates of evolution are typically slower than their pathogens (because their generation times are longer), hosts are usually at an evolutionary disadvantage. This section will explore where pathogens survive—both inside and outside hosts—and some of the many ways they move from one host to another.

Reservoirs and Carriers

For pathogens to persist over long periods of time they require reservoirs where they normally reside. Reservoirs can be living organisms or nonliving sites. Nonliving reservoirs can include soil and water in the environment. These may naturally harbor the organism because it may grow in that environment. These environments may also become contaminated with pathogens in human feces, pathogens shed by intermediate hosts, or pathogens contained in the remains of intermediate hosts.

Pathogens may have mechanisms of dormancy or resilience that allow them to survive (but typically not to reproduce) for varying periods of time in nonliving environments. For example, Clostridium tetani survives in the soil and in the presence of oxygen as a resistant endospore. Although many viruses are soon destroyed once in contact with air, water, or other non-physiological conditions, certain types are capable of persisting outside of a living cell for varying amounts of time. For example, a study that looked at the ability of influenza viruses to infect a cell culture after varying amounts of time on a banknote showed survival times from 48 hours to 17 days, depending on how they were deposited on the banknote.[1] On the other hand, cold-causing rhinoviruses are somewhat fragile, typically surviving less than a day outside of physiological fluids.

A human acting as a reservoir of a pathogen may or may not be capable of transmitting the pathogen, depending on the stage of infection and the pathogen. To help prevent the spread of disease among school children, the CDC has developed guidelines based on the risk of transmission during the course of the disease. For example, children with chickenpox are considered contagious for five days from the start of the rash, whereas children with most gastrointestinal illnesses should be kept home for 24 hours after the symptoms disappear.

An individual capable of transmitting a pathogen without displaying symptoms is referred to as a carrier. A passive carrier is contaminated with the pathogen and can mechanically transmit it to another host; however, a passive carrier is not infected. For example, a health-care professional who fails to wash his hands after seeing a patient harboring an infectious agent could become a passive carrier, transmitting the pathogen to another patient who becomes infected.

By contrast, an active carrier is an infected individual who can transmit the disease to others. An active carrier may or may not exhibit signs or symptoms of infection. For example, active carriers may transmit the disease during the incubation period (before they show signs and symptoms) or the period of convalescence (after symptoms have subsided). Active carriers who do not present signs or symptoms of disease despite infection are called asymptomatic carriers. Pathogens such as hepatitis B virus, herpes simplex virus, and HIV are frequently transmitted by asymptomatic carriers. Mary Mallon, better known as Typhoid Mary, is a famous historical example of an asymptomatic carrier. An Irish immigrant, Mallon worked as a cook for households in and around New York City between 1900 and 1915. In each household, the residents developed typhoid fever (caused by Salmonella typhi) a few weeks after Mallon started working. Later investigations determined that Mallon was responsible for at least 122 cases of typhoid fever, five of which were fatal.[2] See Eye on Ethics: Typhoid Mary for more about the Mallon case.

A pathogen may have more than one living reservoir. In zoonotic diseases, animals act as reservoirs of human disease and transmit the infectious agent to humans through direct or indirect contact. In some cases, the disease also affects the animal, but in other cases the animal is asymptomatic.

In parasitic infections, the parasite’s preferred host is called the definitive host. In parasites with complex life cycles, the definitive host is the host in which the parasite reaches sexual maturity. Some parasites may also infect one or more intermediate hosts in which the parasite goes through several immature life cycle stages or reproduces asexually.

Link to Learning

George Soper, the sanitary engineer who traced the typhoid outbreak to Mary Mallon, gives an account of his investigation, an example of descriptive epidemiology, in “The Curious Career of Typhoid Mary”.

Check Your Understanding

- List some nonliving reservoirs for pathogens.

- Explain the difference between a passive carrier and an active carrier.

Transmission

Regardless of the reservoir, transmission must occur for an infection to spread. First, transmission from the reservoir to the individual must occur. Then, the individual must transmit the infectious agent to other susceptible individuals, either directly or indirectly. Pathogenic microorganisms employ diverse transmission mechanisms.

Contact Transmission

Contact transmission includes direct contact or indirect contact. Person-to-person transmission is a form of direct contact transmission. Here the agent is transmitted by physical contact between two individuals (Figure 16.9) through actions such as touching, kissing, sexual intercourse, or droplet sprays. Direct contact can be categorized as vertical, horizontal, or droplet transmission. Vertical direct contact transmission occurs when pathogens are transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding. Other kinds of direct contact transmission are called horizontal direct contact transmission. Often, contact between mucous membranes is required for entry of the pathogen into the new host, although skin-to-skin contact can lead to mucous membrane contact if the new host subsequently touches a mucous membrane. Contact transmission may also be site-specific; for example, some diseases can be transmitted by sexual contact but not by other forms of contact.

When an individual coughs or sneezes, small droplets of mucus that may contain pathogens are ejected. This leads to direct droplet transmission, which refers to droplet transmission of a pathogen to a new host over distances of one meter or less. A wide variety of diseases are transmitted by droplets, including influenza and many forms of pneumonia. Transmission over distances greater than one meter is called airborne transmission.

Indirect contact transmission involves inanimate objects called fomites that become contaminated by pathogens from an infected individual or reservoir (Figure 16.10). For example, an individual with the common cold may sneeze, causing droplets to land on a fomite such as a tablecloth or carpet, or the individual may wipe her nose and then transfer mucus to a fomite such as a doorknob or towel. Transmission occurs indirectly when a new susceptible host later touches the fomite and transfers the contaminated material to a susceptible portal of entry. Fomites can also include objects used in clinical settings that are not properly sterilized, such as syringes, needles, catheters, and surgical equipment. Pathogens transmitted indirectly via such fomites are a major cause of healthcare-associated infections (see Controlling Microbial Growth).

Vehicle Transmission

The term vehicle transmission refers to the transmission of pathogens through vehicles such as water, food, and air. Water contamination through poor sanitation methods leads to waterborne transmission of disease. Waterborne disease remains a serious problem in many regions throughout the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that contaminated drinking water is responsible for more than 500,000 deaths each year.[3] Similarly, food contaminated through poor handling or storage can lead to foodborne transmission of disease (Figure 16.11).

Dust and fine particles known as aerosols, which can float in the air, can carry pathogens and facilitate the airborne transmission of disease. For example, dust particles are the dominant mode of transmission of hantavirus to humans. Hantavirus is found in mouse feces, urine, and saliva, but when these substances dry, they can disintegrate into fine particles that can become airborne when disturbed; inhalation of these particles can lead to a serious and sometimes fatal respiratory infection.

Although droplet transmission over short distances is considered contact transmission as discussed above, longer distance transmission of droplets through the air is considered vehicle transmission. Unlike larger particles that drop quickly out of the air column, fine mucus droplets produced by coughs or sneezes can remain suspended for long periods of time, traveling considerable distances. In certain conditions, droplets desiccate quickly to produce a droplet nucleus that is capable of transmitting pathogens; air temperature and humidity can have an impact on effectiveness of airborne transmission.

Tuberculosis is often transmitted via airborne transmission when the causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is released in small particles with coughs. Because tuberculosis requires as few as 10 microbes to initiate a new infection, patients with tuberculosis must be treated in rooms equipped with special ventilation, and anyone entering the room should wear a mask.

Vector Transmission

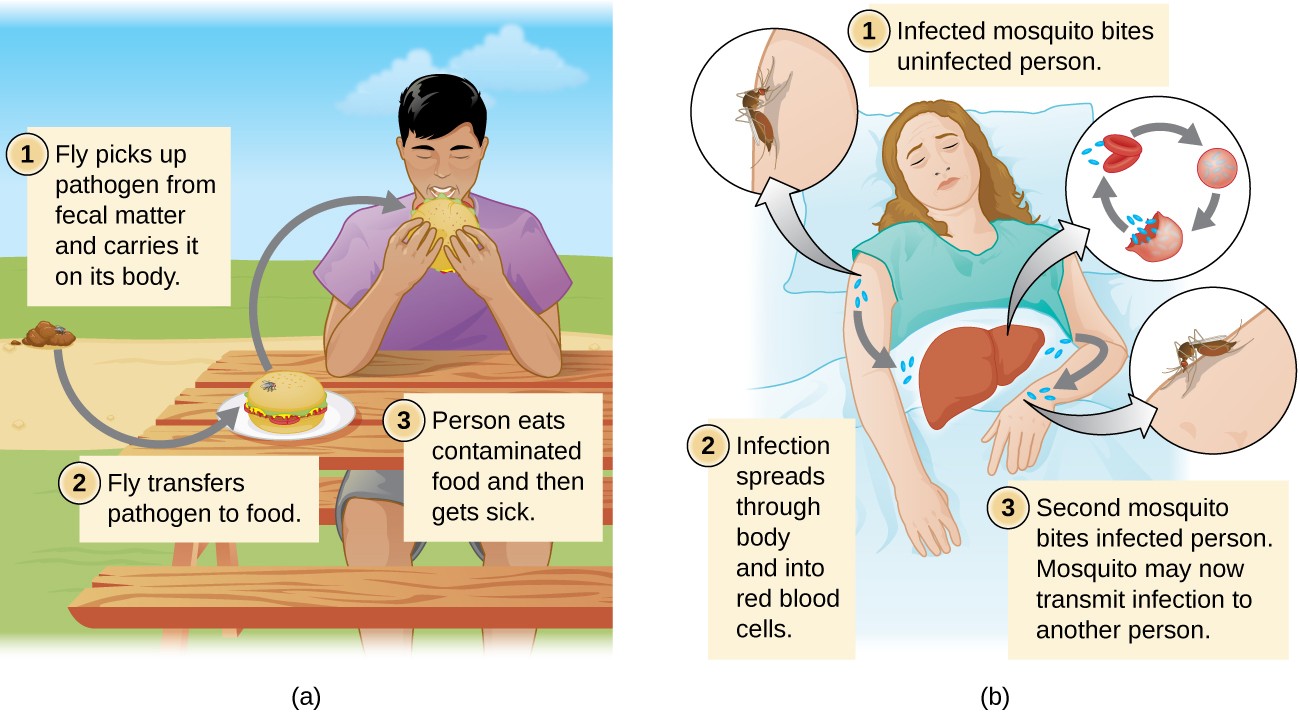

Diseases can also be transmitted by a mechanical or biological vector, an animal (typically an arthropod) that carries the disease from one host to another. Mechanical transmission is facilitated by a mechanical vector, an animal that carries a pathogen from one host to another without being infected itself. For example, a fly may land on fecal matter and later transmit bacteria from the feces to food that it lands on; a human eating the food may then become infected by the bacteria, resulting in a case of diarrhea or dysentery (Figure 16.12).

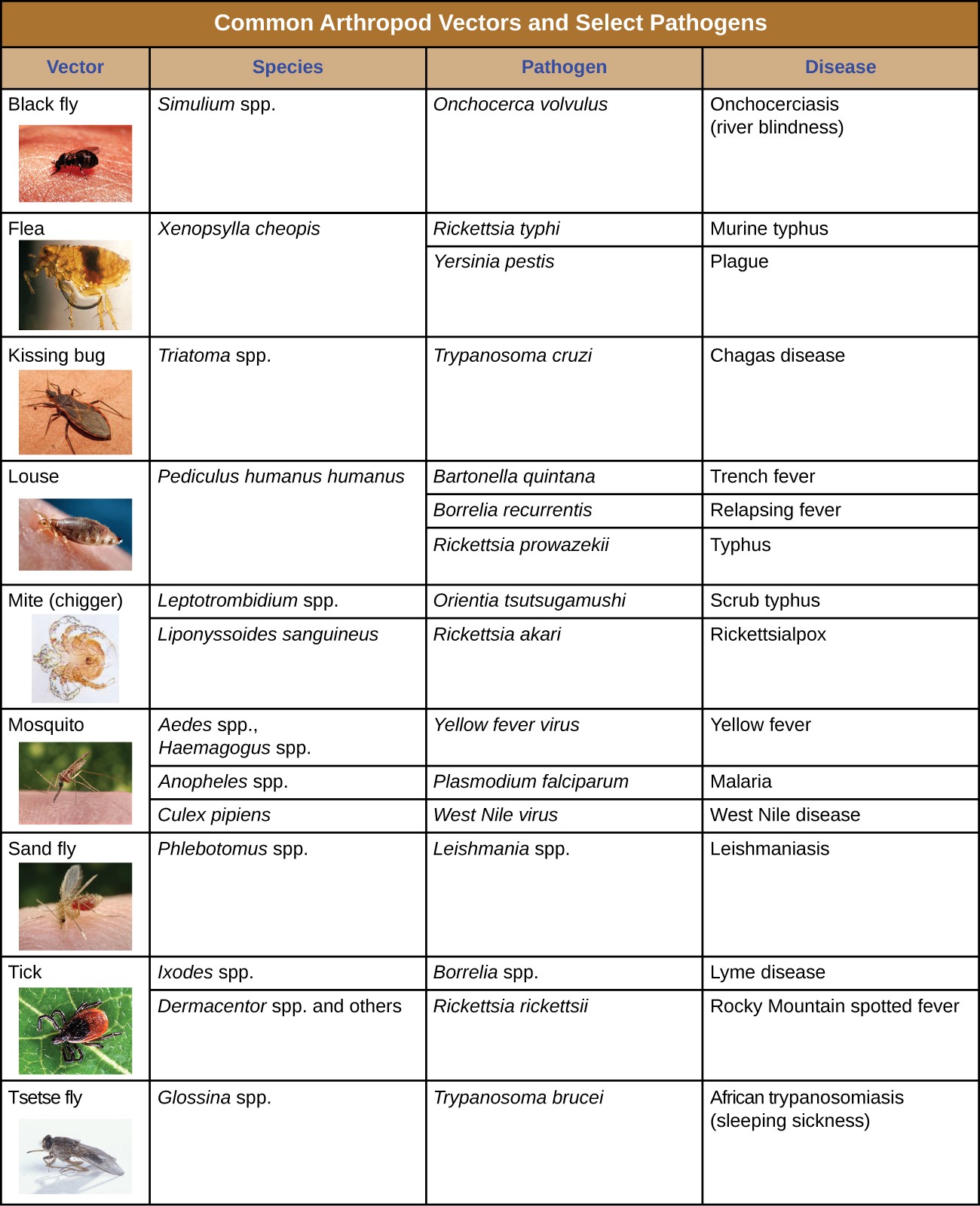

Biological transmission occurs when the pathogen reproduces within a biological vector that transmits the pathogen from one host to another (Figure 16.12). Arthropods are the main vectors responsible for biological transmission (Figure 16.13). Most arthropod vectors transmit the pathogen by biting the host, creating a wound that serves as a portal of entry. The pathogen may go through part of its reproductive cycle in the gut or salivary glands of the arthropod to facilitate its transmission through the bite. For example, hemipterans (called “kissing bugs” or “assassin bugs”) transmit Chagas disease to humans by defecating when they bite, after which the human scratches or rubs the infected feces into a mucous membrane or break in the skin.

Biological insect vectors include mosquitoes, which transmit malaria and other diseases, and lice, which transmit typhus. Other arthropod vectors can include arachnids, primarily ticks, which transmit Lyme disease and other diseases, and mites, which transmit scrub typhus and rickettsial pox. Biological transmission, because it involves survival and reproduction within a parasitized vector, complicates the biology of the pathogen and its transmission. There are also important non-arthropod vectors of disease, including mammals and birds. Various species of mammals can transmit rabies to humans, usually by means of a bite that transmits the rabies virus. Chickens and other domestic poultry can transmit avian influenza to humans through direct or indirect contact with avian influenza virus A shed in the birds’ saliva, mucous, and feces.

a) Step 1: fly picks up pathogen from fecal matter and carries it on its body. 2: Fly transfers pathogen to food. 3: Person eats contaminated food and gets sick. B) Step 1: Infected mosquito bites uninfected person. 2: Infections spreads through body and into red blood cells. 3: Second mosquito bites infected person. Mosquito may now transmit infection to another person.

Table titled common arthropod vectors and selected pathogens. Columns: Vector; species, pathogen; disease. Black fly; Simulium spp.; Onchocerca volvulus; Onchocerciasis (river blindness). Flea (has 2). Ctenocephalides felis; Bartonella henselae; cat scratch disease. Xenopsylla cheopis (has 2). Rickettsia typhi; murine typhus. Yersinia pestis; plague. Kissing bug, Triatoma spp.; Trypanosoma cruzi; Chagas disease. Louse; Pediculus humanus humanus (has 3) Bartonella quintana; trench fever. Borrelia recurrentis; relapsing fever. Rickettsia prowazekii; typhus. Mite/chigger (has 2). Leptotrombidium spp.; Orientia tsutsugamushi; scrub typhus. Rickettsia akari; rickettsialpox. Moquito (has 3). Aedes spp and Haemogogus spp.; yellow fever virus; yellow fever. Anopheles spp.; Plasmodium falciparum; malaria. Cutex pipiens; west nile virus, west nile disease. Sand fly; Phlebotomus spp.; Leishmania spp.; Leishmaniasis. Tick (has 2): Ixodes spp; Borrelia spp.; Lyme disease. Dermacentor spp. And others; Rickettsi rickettsia; rocky mountain spotted fever. Tsetse fly; Glossina spp. Trypanosoma brucei Trypanosomiasis (sleepting sickness).

Check Your Understanding

- Describe how diseases can be transmitted through the air.

- Explain the difference between a mechanical vector and a biological vector.

Eye on Ethics

Using GMOs to Stop the Spread of Zika

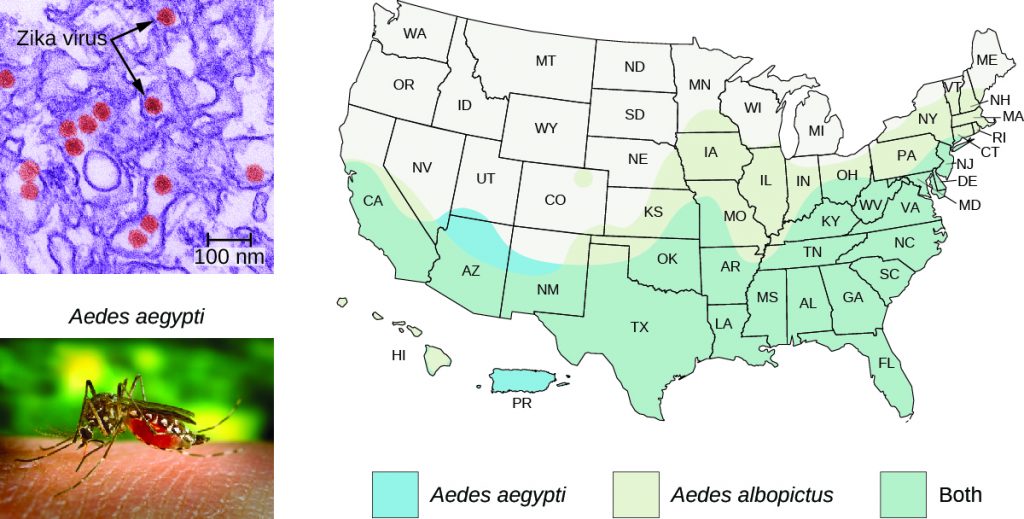

In 2016, an epidemic of the Zika virus was linked to a high incidence of birth defects in South America and Central America. As winter turned to spring in the northern hemisphere, health officials correctly predicted the virus would spread to North America, coinciding with the breeding season of its major vector, the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

The range of the A. aegypti mosquito extends well into the southern United States (Figure 16.14). Because these same mosquitoes serve as vectors for other problematic diseases (dengue fever, yellow fever, and others), various methods of mosquito control have been proposed as solutions. Chemical pesticides have been used effectively in the past, and are likely to be used again; but because chemical pesticides can have negative impacts on the environment, some scientists have proposed an alternative that involves genetically engineering A. aegypti so that it cannot reproduce. This method, however, has been the subject of some controversy.

One method that has worked in the past to control pests, with little apparent downside, has been sterile male introductions. This method controlled the screw-worm fly pest in the southwest United States and fruit fly pests of fruit crops. In this method, males of the target species are reared in the lab, sterilized with radiation, and released into the environment where they mate with wild females, who subsequently bear no live offspring. Repeated releases shrink the pest population.

A similar method, taking advantage of recombinant DNA technology,[4] introduces a dominant lethal allele into male mosquitoes that is suppressed in the presence of tetracycline (an antibiotic) during laboratory rearing. The males are released into the environment and mate with female mosquitoes. Unlike the sterile male method, these matings produce offspring, but they die as larvae from the lethal gene in the absence of tetracycline in the environment. As of 2016, this method has yet to be implemented in the United States, but a UK company tested the method in Piracicaba, Brazil, and found an 82% reduction in wild A. aegypti larvae and a 91% reduction in dengue cases in the treated area.[5] In August 2016, amid news of Zika infections in several Florida communities, the FDA gave the UK company permission to test this same mosquito control method in Key West, Florida, pending compliance with local and state regulations and a referendum in the affected communities.

The use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) to control a disease vector has its advocates as well as its opponents. In theory, the system could be used to drive the A. aegypti mosquito extinct—a noble goal according to some, given the damage they do to human populations.[6] But opponents of the idea are concerned that the gene could escape the species boundary of A. aegypti and cause problems in other species, leading to unforeseen ecological consequences. Opponents are also wary of the program because it is being administered by a for-profit corporation, creating the potential for conflicts of interest that would have to be tightly regulated; and it is not clear how any unintended consequences of the program could be reversed.

There are other epidemiological considerations as well. Aedes aegypti is apparently not the only vector for the Zika virus. Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito, is also a vector for the Zika virus.[7] A. albopictus is now widespread around the planet including much of the United States (Figure 16.14). Many other mosquitoes have been found to harbor Zika virus, though their capacity to act as vectors is unknown.[8] Genetically modified strains of A. aegypti will not control the other species of vectors. Finally, the Zika virus can apparently be transmitted sexually between human hosts, from mother to child, and possibly through blood transfusion. All of these factors must be considered in any approach to controlling the spread of the virus.

Clearly there are risks and unknowns involved in conducting an open-environment experiment of an as-yet poorly understood technology. But allowing the Zika virus to spread unchecked is also risky. Does the threat of a Zika epidemic justify the ecological risk of genetically engineering mosquitos? Are current methods of mosquito control sufficiently ineffective or harmful that we need to try untested alternatives? These are the questions being put to public health officials now.

Micrograph of brown dots of about 50 nm inside cells; dots re labeled Zika virus. Photo of mosquito labeled Aedes aegypti. Map of where mosquitoes are found in the US. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus are both found in the lower half of the US, reaching up to Connecticut, Missouri, and California. Aedes albopictus reaches further north in the eastern part o the country; through Minnosota. Aedes aegypti reaches a bit further into Utah and is in Puerto Rico.

Quarantining

Individuals suspected or known to have been exposed to certain contagious pathogens may be quarantined, or isolated to prevent transmission of the disease to others. Hospitals and other health-care facilities generally set up special wards to isolate patients with particularly hazardous diseases such as tuberculosis or Ebola (Figure 16.15). Depending on the setting, these wards may be equipped with special air-handling methods, and personnel may implement special protocols to limit the risk of transmission, such as personal protective equipment or the use of chemical disinfectant sprays upon entry and exit of medical personnel.

The duration of the quarantine depends on factors such as the incubation period of the disease and the evidence suggestive of an infection. The patient may be released if signs and symptoms fail to materialize when expected or if preventive treatment can be administered in order to limit the risk of transmission. If the infection is confirmed, the patient may be compelled to remain in isolation until the disease is no longer considered contagious.

In the United States, public health authorities may only quarantine patients for certain diseases, such as cholera, diphtheria, infectious tuberculosis, and strains of influenza capable of causing a pandemic. Individuals entering the United States or moving between states may be quarantined by the CDC if they are suspected of having been exposed to one of these diseases. Although the CDC routinely monitors entry points to the United States for crew or passengers displaying illness, quarantine is rarely implemented.

Healthcare-Associated (Nosocomial) Infections

Hospitals, retirement homes, and prisons attract the attention of epidemiologists because these settings are associated with increased incidence of certain diseases. Higher rates of transmission may be caused by characteristics of the environment itself, characteristics of the population, or both. Consequently, special efforts must be taken to limit the risks of infection in these settings.

Infections acquired in health-care facilities, including hospitals, are called nosocomial infections or healthcare- associated infections (HAI). HAIs are often connected with surgery or other invasive procedures that provide the pathogen with access to the portal of infection. For an infection to be classified as an HAI, the patient must have been admitted to the health-care facility for a reason other than the infection. In these settings, patients suffering from primary disease are often afflicted with compromised immunity and are more susceptible to secondary infection and opportunistic pathogens.

In 2011, more than 720,000 HAIs occurred in hospitals in the United States, according to the CDC. About 22% of these HAIs occurred at a surgical site, and cases of pneumonia accounted for another 22%; urinary tract infections accounted for an additional 13%, and primary bloodstream infections 10%.[9] Such HAIs often occur when pathogens are introduced to patients’ bodies through contaminated surgical or medical equipment, such as catheters and respiratory ventilators. Health-care facilities seek to limit nosocomial infections through training and hygiene protocols such as those described in Control of Microbial Growth.

Check Your Understanding

- Give some reasons why HAIs occur.

Footnotes

Yves Thomas, Guido Vogel, Werner Wunderli, Patricia Suter, Mark Witschi, Daniel Koch, Caroline Tapparel, and Laurent Kaiser. “Survival of Influenza Virus on Banknotes.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 74, no. 10 (2008): 3002–3007.

Filio Marineli, Gregory Tsoucalas, Marianna Karamanou, and George Androutsos. “Mary Mallon (1869–1938) and the History of Typhoid Fever.” Annals of Gastroenterology 26 (2013): 132–134. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3959940/pdf/ AnnGastroenterol-26-132.pdf.

World Health Organization. Fact sheet No. 391—Drinking Water. June 2005. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs391/en.<

Blandine Massonnet-Bruneel, Nicole Corre-Catelin, Renaud Lacroix, Rosemary S. Lees, Kim Phuc Hoang, Derric Nimmo, Luke Alphey, and Paul Reiter. “Fitness of Transgenic Mosquito Aedes aegypti Males Carrying a Dominant Lethal Genetic System.” PLOS ONE 8, no. 5 (2013): e62711.

Richard Levine. “Cases of Dengue Drop 91 Percent Due to Genetically Modified Mosquitoes.” Entomology Today.

Cases of Dengue Drop 91 Percent Due to Genetically Modified Mosquitoes

Olivia Judson. “A Bug’s Death.” The New York Times, September 25, 2003. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/25/opinion/a-bug-s- death.html.

Gilda Grard, Mélanie Caron, Illich Manfred Mombo, Dieudonné Nkoghe, Statiana Mboui Ondo, Davy Jiolle, Didier Fontenille, Christophe Paupy, and Eric Maurice Leroy. “Zika Virus in Gabon (Central Africa)–2007: A New Threat from Aedes albopictus?” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 8, no. 2 (2014): e2681.

Constância F.J. Ayres. “Identification of Zika Virus Vectors and Implications for Control.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 16, no. 3 (2016): 278–279.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “HAI Data and Statistics.” 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/hai/surveillance. Accessed Jan 2,