4.1 – Prokaryote Habitats, Relationships, and Microbiomes

Scientists have studied prokaryotes for centuries, but it wasn’t until 1966 that scientist Thomas Brock (1926–) discovered that certain bacteria can live in boiling water. This led many to wonder whether prokaryotes may also live in other extreme environments, such as at the bottom of the ocean, at high altitudes, or inside volcanoes, or even on other planets.

Prokaryotes have an important role in changing, shaping, and sustaining the entire biosphere. They can produce proteins and other substances used by molecular biologists in basic research and in medicine and industry. For example, the bacterium Shewanella lives in the deep sea, where oxygen is scarce. It grows long appendages, which have special sensors used to seek the limited oxygen in its environment. It can also digest toxic waste and generate electricity. Other species of prokaryotes can produce more oxygen than the entire Amazon rainforest, while still others supply plants, animals, and humans with usable forms of nitrogen; and inhabit our body, protecting us from harmful microorganisms and producing some vitally important substances. This chapter will examine the diversity, structure, and function of prokaryotes.

Learning Objectives

- Identify and describe unique examples of prokaryotes in various habitats on earth

- Identify and describe symbiotic relationships

- Compare normal/commensal/resident microbiota to transient microbiota

- Explain how prokaryotes are classified

All living organisms are classified into three domains of life: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya. In this chapter, we will focus on the domains Archaea and Bacteria. Archaea and bacteria are unicellular prokaryotic organisms. Unlike eukaryotes, they have no nuclei or any other membrane-bound organelles.

Prokaryote Habitats and Functions

Prokaryotes are ubiquitous. They can be found everywhere on our planet, even in hot springs, in the Antarctic ice shield, and under extreme pressure two miles under water. One bacterium, Paracoccus denitrificans, has even been shown to survive when scientists removed it from its native environment (soil) and used a centrifuge to subject it to forces of gravity as strong as those found on the surface of Jupiter.

Prokaryotes also are abundant on and within the human body. According to a report by National Institutes of Health, prokaryotes, especially bacteria, outnumber human cells 10:1.1 More recent studies suggest the ratio could be closer to 1:1, but even that ratio means that there are a great number of bacteria within the human body.2 Bacteria thrive in the human mouth, nasal cavity, throat, ears, gastrointestinal tract, and vagina. Large colonies of bacteria can be found on healthy human skin, especially in moist areas (armpits, navel, and areas behind ears). However, even drier areas of the skin are not free from bacteria.

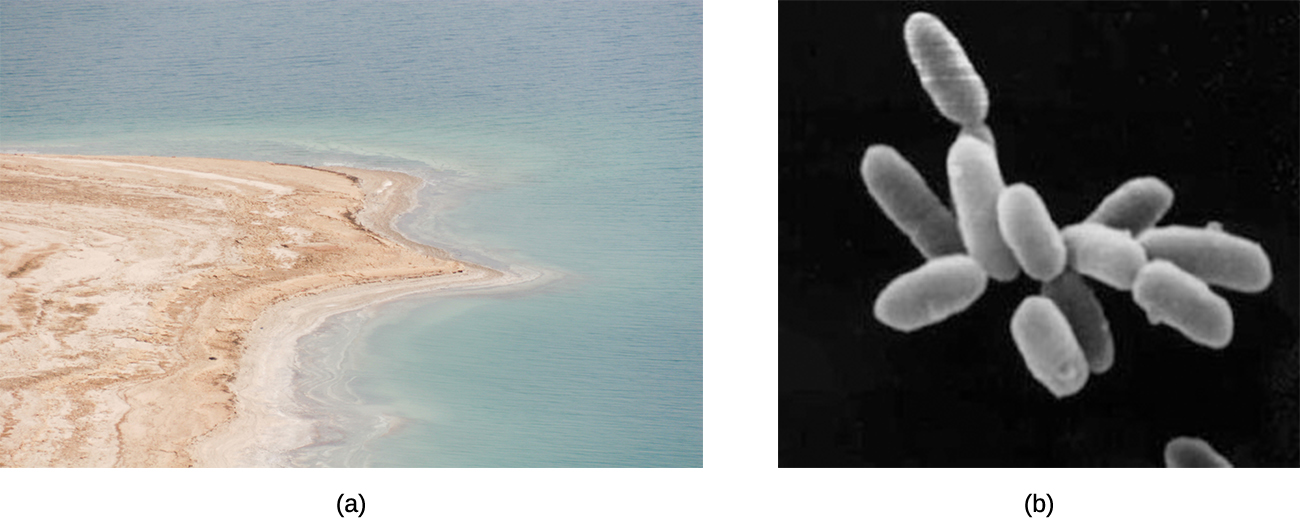

The existence of prokaryotes is very important for the stability and thriving of ecosystems. For example, they are a necessary part of soil formation and stabilization processes through the breakdown of organic matter and development of biofilms. One gram of soil contains up to 10 billion microorganisms (most of them prokaryotic) belonging to about 1,000 species. Many species of bacteria use substances released from plant roots, such as acids and carbohydrates, as nutrients. The bacteria metabolize these plant substances and release the products of bacterial metabolism back to the soil, forming humus and thus increasing the soil’s fertility. In salty lakes such as the Dead Sea (Figure 4.2), salt-loving halobacteria decompose dead brine shrimp and nourish young brine shrimp and flies with the products of bacterial metabolism.

In addition to living in the ground and the water, prokaryotic microorganisms are abundant in the air, even high in the atmosphere. There may be up to 2,000 different kinds of bacteria in the air, similar to their diversity in the soil.

Prokaryotes can be found everywhere on earth because they are extremely resilient and adaptable. They are often metabolically flexible, which means that they might easily switch from one energy source to another, depending on the availability of the sources, or from one metabolic pathway to another. For example, certain prokaryotic cyanobacteria can switch from a conventional type of lipid metabolism, which includes production of fatty aldehydes, to a different type of lipid metabolism that generates biofuel, such as fatty acids and wax esters. Groundwater bacteria store complex high-energy carbohydrates when grown in pure groundwater, but they metabolize these molecules when the groundwater is enriched with phosphates. Some bacteria get their energy by reducing sulfates into sulfides, but can switch to a different metabolic pathway when necessary, producing acids and free hydrogen ions.

Prokaryotes perform functions vital to life on earth by capturing (or “fixing”) and recycling elements like carbon and nitrogen. Organisms such as animals require organic carbon to grow, but, unlike prokaryotes, they are unable to use inorganic carbon sources like carbon dioxide. Thus, animals rely on prokaryotes to convert carbon dioxide into organic carbon products that they can use. This process of converting carbon dioxide to organic carbon products is called carbon fixation.

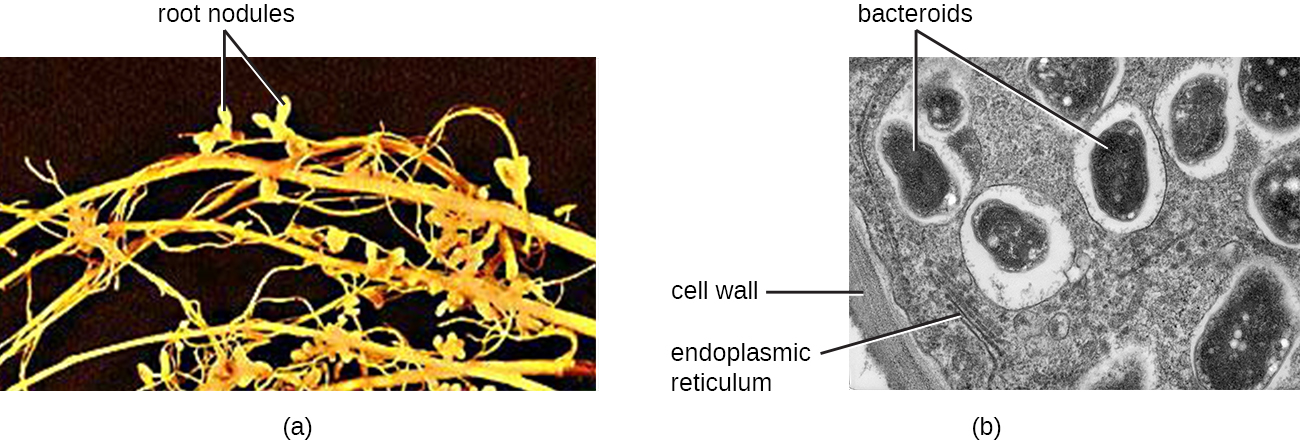

Plants and animals also rely heavily on prokaryotes for nitrogen fixation, the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, a compound that some plants can use to form many different biomolecules necessary to their survival. Bacteria in the genus Rhizobium, for example, are nitrogen-fixing bacteria; they live in the roots of legume plants such as clover, alfalfa, and peas (Figure 4.3). Ammonia produced by Rhizobium helps these plants to survive by enabling them to make building blocks of nucleic acids. In turn, these plants may be eaten by animals—sustaining their growth and survival—or they may die, in which case the products of nitrogen fixation will enrich the soil and be used by other plants.

A) photo of roots with small nodules labeled root nodules. B) A micrograph of a root nodule. A thick cell wall is on the outside. Lines inside are labeled endoplasmic reticulum. Large ovals in clear structures are labeled bacteroids.

Another positive function of prokaryotes is in cleaning up the environment. Recently, some researchers focused on the diversity and functions of prokaryotes in manmade environments. They found that some bacteria play a unique role in degrading toxic chemicals that pollute water and soil.3

Despite all of the positive and helpful roles prokaryotes play, some are human pathogens that may cause illness or infection when they enter the body. In addition, some bacteria can contaminate food, causing spoilage or foodborne illness, which makes them subjects of concern in food preparation and safety. Less than 1% of prokaryotes (all of them bacteria) are thought to be human pathogens, but collectively these species are responsible for a large number of the diseases that afflict humans.

Besides pathogens, which have a direct impact on human health, prokaryotes also affect humans in many indirect ways. For example, prokaryotes are now thought to be key players in the processes of climate change. In recent years, as temperatures in the earth’s polar regions have risen, soil that was formerly frozen year-round (permafrost) has begun to thaw. Carbon trapped in the permafrost is gradually released and metabolized by prokaryotes. This produces massive amounts of carbon dioxide and methane, greenhouse gases that escape into the atmosphere and contribute to the greenhouse effect.

Check Your Understanding

- In what types of environments can prokaryotes be found?

- Name some ways that plants and animals rely on prokaryotes.

Symbiotic Relationships

As we have learned, prokaryotic microorganisms can associate with plants and animals. Often, this association results in unique relationships between organisms. For example, bacteria living on the roots or leaves of a plant get nutrients from the plant and, in return, produce substances that protect the plant from pathogens. On the other hand, some bacteria are plant pathogens that use mechanisms of infection similar to bacterial pathogens of animals and humans.

Prokaryotes live in a community, or a group of interacting populations of organisms. A population is a group of individual organisms belonging to the same biological species and limited to a certain geographic area. Populations can have cooperative interactions, which benefit the populations, or competitive interactions, in which one population competes with another for resources. The study of these interactions between microbial populations and their environment is called microbial ecology.

Any interaction between different species that are associated with each other within a community is called symbiosis. Such interactions fall along a continuum between opposition and cooperation. Interactions in a symbiotic relationship may be beneficial or harmful, or have no effect on one or both of the species involved. Table 4.1 summarizes the main types of symbiotic interactions among prokaryotes.

Types of Symbiotic Relationships

| Type | Population A | Population B |

|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Benefitted | Benefitted |

| Amensalism | Harmed | Unaffected |

| Commensalism | Benefitted | Unaffected |

| Neutralism | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Parasitism | Benefitted | Harmed |

When two species benefit from each other, the symbiosis is called mutualism (or syntropy, or crossfeeding). For example, humans have a mutualistic relationship with the bacterium Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, which lives in the intestinal tract. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron digests complex polysaccharide plant materials that human digestive enzymes cannot break down, converting them into monosaccharides that can be absorbed by human cells. Humans also have a mutualistic relationship with certain strains of Escherichia coli, another bacterium found in the gut. E. coli relies on intestinal contents for nutrients, and humans derive certain vitamins from E. coli, particularly vitamin K, which is required for the formation of blood clotting factors. (This is only true for some strains of E. coli, however. Other strains are pathogenic and do not have a mutualistic relationship with humans.)

A type of symbiosis in which one population harms another but remains unaffected itself is called amensalism. In the case of bacteria, some amensalist species produce bactericidal substances that kill other species of bacteria. The microbiota of the skin is composed of a variety of bacterial species, including Staphylococcus epidermidis and Propionibacterium acnes. Although both species have the potential to cause infectious diseases when protective barriers are breached, they both produce a variety of antibacterial bacteriocins and bacteriocin-like compounds. S. epidermidis and P. acnes are unaffected by the bacteriocins and bacteriocin-like compounds they produce, but these compounds can target and kill other potential pathogens.

In another type of symbiosis, called commensalism, one organism benefits while the other is unaffected. This occurs when the bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis uses the dead cells of the human skin as nutrients. Billions of these bacteria live on our skin, but in most cases (especially when our immune system is healthy), we do not react to them in any way. S. epidermidis provides an excellent example of how the classifications of symbiotic relationships are not always distinct. One could also consider the symbiotic relationship of S. epidermidis with humans as mutualism. Humans provide a food source of dead skin cells to the bacterium, and in turn the production of bacteriocin can provide an defense against potential pathogens.

If neither of the symbiotic organisms is affected in any way, we call this type of symbiosis neutralism. An example of neutralism is the coexistence of metabolically active (vegetating) bacteria and endospores (dormant, metabolically passive bacteria). For example, the bacterium Bacillus anthracis typically forms endospores in soil when conditions are unfavorable. If the soil is warmed and enriched with nutrients, some B. anthracis endospores germinate and remain in symbiosis with other species of endospores that have not germinated.

A type of symbiosis in which one organism benefits while harming the other is called parasitism. The relationship between humans and many pathogenic prokaryotes can be characterized as parasitic because these organisms invade the body, producing toxic substances or infectious diseases that cause harm. Diseases such as tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, tuberculosis, and leprosy all arise from interactions between bacteria and humans.

Scientists have coined the term microbiome to refer to all prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms that are associated with a certain organism or environment. Within the human microbiome, there are resident microbiota and transient microbiota. The resident microbiota consists of microorganisms that constantly live in or on our bodies. The term transient microbiota refers to microorganisms that are only temporarily found in the human body, and these may include pathogenic microorganisms. Hygiene and diet can alter both the resident and transient microbiota.

The resident microbiota is amazingly diverse, not only in terms of the variety of species but also in terms of the preference of different microorganisms for different areas of the human body. For example, in the human mouth, there are thousands of commensal or mutualistic species of bacteria. Some of these bacteria prefer to inhabit the surface of the tongue, whereas others prefer the internal surface of the cheeks, and yet others prefer the front or back teeth or gums. The inner surface of the cheek has the least diverse microbiota because of its exposure to oxygen. By contrast, the crypts of the tongue and the spaces between teeth are two sites with limited oxygen exposure, so these sites have more diverse microbiota, including bacteria living in the absence of oxygen (e.g., Bacteroides, Fusobacterium). Differences in the oral microbiota between randomly chosen human individuals are also significant. Studies have shown, for example, that the prevalence of such bacteria as Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Neisseria, and others was dramatically different when compared between individuals.4

There are also significant differences between the microbiota of different sites of the same human body. The inner surface of the cheek has a predominance of Streptococcus, whereas in the throat, the palatine tonsil, and saliva, there are two to three times fewer Streptococcus, and several times more Fusobacterium. In the plaque removed from gums, the predominant bacteria belong to the genus Fusobacterium. However, in the intestine, both Streptococcus and Fusobacterium disappear, and the genus Bacteroides becomes predominant.

Not only can the microbiota vary from one body site to another, the microbiome can also change over time within the same individual. Humans acquire their first inoculations of normal flora during natural birth and shortly after birth. Before birth, there is a rapid increase in the population of Lactobacillus spp. in the vagina, and this population serves as the first colonization of microbiota during natural birth. After birth, additional microbes are acquired from health-care providers, parents, other relatives, and individuals who come in contact with the baby. This process establishes a microbiome that will continue to evolve over the course of the individual’s life as new microbes colonize and are eliminated from the body. For example, it is estimated that within a 9-hour period, the microbiota of the small intestine can change so that half of the microbial inhabitants will be different.5 The importance of the initial Lactobacillus colonization during vaginal child birth is highlighted by studies demonstrating a higher incidence of diseases in individuals born by cesarean section, compared to those born vaginally. Studies have shown that babies born vaginally are predominantly colonized by vaginal lactobacillus, whereas babies born by cesarean section are more frequently colonized by microbes of the normal skin microbiota, including common hospital-acquired pathogens.

Throughout the body, resident microbiotas are important for human health because they occupy niches that might be otherwise taken by pathogenic microorganisms. For instance, Lactobacillus spp. are the dominant bacterial species of the normal vaginal microbiota for most women. lactobacillus produce lactic acid, contributing to the acidity of the vagina and inhibiting the growth of pathogenic yeasts. However, when the population of the resident microbiota is decreased for some reason (e.g., because of taking antibiotics), the pH of the vagina increases, making it a more favorable environment for the growth of yeasts such as Candida albicans. Antibiotic therapy can also disrupt the microbiota of the intestinal tract and respiratory tract, increasing the risk for secondary infections and/or promoting the long-term carriage and shedding of pathogens.

Check Your Understanding

- Explain the difference between cooperative and competitive interactions in microbial communities.

- List the types of symbiosis and explain how each population is affected.

Taxonomy and Systematics

Assigning prokaryotes to a certain species is challenging. They do not reproduce sexually, so it is not possible to classify them according to the presence or absence of interbreeding. Also, they do not have many morphological features. Traditionally, the classification of prokaryotes was based on their shape, staining patterns, and biochemical or physiological differences. More recently, as technology has improved, the nucleotide sequences in genes have become an important criterion of microbial classification.

In 1923, American microbiologist David Hendricks Bergey (1860–1937) published A Manual in Determinative Bacteriology. With this manual, he attempted to summarize the information about the kinds of bacteria known at that time, using Latin binomial classification. Bergey also included the morphological, physiological, and biochemical properties of these organisms. His manual has been updated multiple times to include newer bacteria and their properties. It is a great aid in bacterial taxonomy and methods of characterization of bacteria. A more recent sister publication, the five-volume Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, expands on Bergey’s original manual. It includes a large number of additional species, along with up-to-date descriptions of the taxonomy and biological properties of all named prokaryotic taxa. This publication incorporates the approved names of bacteria as determined by the List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN).

Classification by Staining Patterns

According to their staining patterns, which depend on the properties of their cell walls, bacteria have traditionally been classified into gram-positive, gram-negative, and “atypical,” meaning neither gram-positive nor gram-negative. As explained in Staining Microscopic Specimens, gram-positive bacteria possess a thick peptidoglycan cell wall that retains the primary stain (crystal violet) during the decolorizing step; they remain purple after the gram-stain procedure because the crystal violet dominates the light red/pink color of the secondary counterstain, safranin. In contrast, gram-negative bacteria possess a thin peptidoglycan cell wall that does not prevent the crystal violet from washing away during the decolorizing step; therefore, they appear light red/pink after staining with the safranin. Bacteria that cannot be stained by the standard Gram stain procedure are called atypical bacteria. Included in the atypical category are species of Mycoplasma and Chlamydia. Rickettsia are also considered atypical because they are too small to be evaluated by the Gram stain.

More recently, scientists have begun to further classify gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. They have added a special group of deeply branching bacteria based on a combination of physiological, biochemical, and genetic features. They also now further classify gram-negative bacteria into Proteobacteria, Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides (CFB), and spirochetes.

The deeply branching bacteria are thought to be a very early evolutionary form of bacteria (see Deeply Branching Bacteria). They live in hot, acidic, ultraviolet-light-exposed, and anaerobic (deprived of oxygen) conditions. Proteobacteria is a phylum of very diverse groups of gram-negative bacteria; it includes some important human pathogens (e.g., E. coli and Bordetella pertussis). The CFB group of bacteria includes components of the normal human gut microbiota, like Bacteroides. The spirochetes are spiral-shaped bacteria and include the pathogen Treponema pallidum, which causes syphilis. We will characterize these groups of bacteria in more detail later in the chapter.

Based on their prevalence of guanine and cytosine nucleotides, gram-positive bacteria are also classified into low G+C and high G+C gram-positive bacteria. The low G+C gram-positive bacteria have less than 50% of guanine and cytosine nucleotides in their DNA. They include human pathogens, such as those that cause anthrax (Bacillus anthracis), tetanus (Clostridium tetani), and listeriosis (Listeria monocytogenes). High G+C gram-positive bacteria, which have more than 50% guanine and cytosine nucleotides in their DNA, include the bacteria that cause diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae), tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), and other diseases.

The classifications of prokaryotes are constantly changing as new species are being discovered. We will describe them in more detail, along with the diseases they cause, in later sections and chapters.

Check Your Understanding

- How do scientists classify prokaryotes?

Micro Connections

Human Microbiome Project

The Human Microbiome Project was launched by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2008. One main goal of the project is to create a large repository of the gene sequences of important microbes found in humans, helping biologists and clinicians understand the dynamics of the human microbiome and the relationship between the human microbiota and diseases. A network of labs working together has been compiling the data from swabs of several areas of the skin, gut, and mouth from hundreds of individuals.

One of the challenges in understanding the human microbiome has been the difficulty of culturing many of the microbes that inhabit the human body. It has been estimated that we are only able to culture 1% of the bacteria in nature and that we are unable to grow the remaining 99%. To address this challenge, researchers have used metagenomic analysis, which studies genetic material harvested directly from microbial communities, as opposed to that of individual species grown in a culture. This allows researchers to study the genetic material of all microbes in the microbiome, rather than just those that can be cultured.6

One important achievement of the Human Microbiome Project is establishing the first reference database on microorganisms living in and on the human body. Many of the microbes in the microbiome are beneficial, but some are not. It was found, somewhat unexpectedly, that all of us have some serious microbial pathogens in our microbiota. For example, the conjunctiva of the human eye contains 24 genera of bacteria and numerous pathogenic species.7 A healthy human mouth contains a number of species of the genus Streptococcus, including pathogenic species S. pyogenes and S. pneumoniae.8 This raises the question of why certain prokaryotic organisms exist commensally in certain individuals but act as deadly pathogens in others. Also unexpected was the number of organisms that had never been cultured. For example, in one metagenomic study of the human gut microbiota, 174 new species of bacteria were identified.9

Another goal for the near future is to characterize the human microbiota in patients with different diseases and to find out whether there are any relationships between the contents of an individual’s microbiota and risk for or susceptibility to specific diseases. Analyzing the microbiome in a person with a specific disease may reveal new ways to fight diseases.

Footnotes

[1] Medical Press. “Mouth Bacteria Can Change Their Diet, Supercomputers Reveal.” August 12, 2014. http://medicalxpress.com/news/2014-08-mouth-bacteria-diet-supercomputers-reveal.html. Accessed February 24, 2015.

[2] A. Abbott. “Scientists Bust Myth That Our Bodies Have More Bacteria Than Human Cells: Decades-Old Assumption about Microbiota Revisited.” Nature. http://www.nature.com/news/scientists-bust-myth-that-our-bodies-have-more-bacteria-than-human-cells-1.19136. Accessed June 3, 2016.

[3] A.M. Kravetz “Unique Bacteria Fights Man-Made Chemical Waste.” 2012. http://www.livescience.com/25181-bacteria-strain-cleans-up-toxins-nsf-bts.html. Accessed March 9, 2015.

[4] E.M. Bik et al. “Bacterial Diversity in the Oral Cavity of 10 Healthy Individuals.” The ISME Journal 4 no. 8 (2010):962–974.

[5] C.C. Booijink et al. “High Temporal and Intra-Individual Variation Detected in the Human Ileal Microbiota.” Environmental Microbiology 12 no. 12 (2010):3213–3227.

[6] National Institutes of Health. “Human Microbiome Project. Overview.” http://commonfund.nih.gov/hmp/overview. Accessed June 7, 2016.

[7] Q. Dong et al. “Diversity of Bacteria at Healthy Human Conjunctiva.” Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 52 no. 8 (2011):5408–5413.

[8] F.E. Dewhirst et al. “The Human Oral Microbiome.” Journal of Bacteriology 192 no. 19 (2010):5002–5017.

[9] J.C. Lagier et al. “Microbial Culturomics: Paradigm Shift in the Human Gut Microbiome Study.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 18 no. 12 (2012):1185–1193.