5.1 – Unicellular Eukaryotic Parasites

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the general characteristics of unicellular eukaryotic parasites

- Describe the general life cycles and modes of reproduction in unicellular eukaryotic parasites

- Identify challenges associated with classifying unicellular eukaryotes

- Explain the taxonomic scheme used for unicellular eukaryotes

- Give examples of infections caused by unicellular eukaryotes

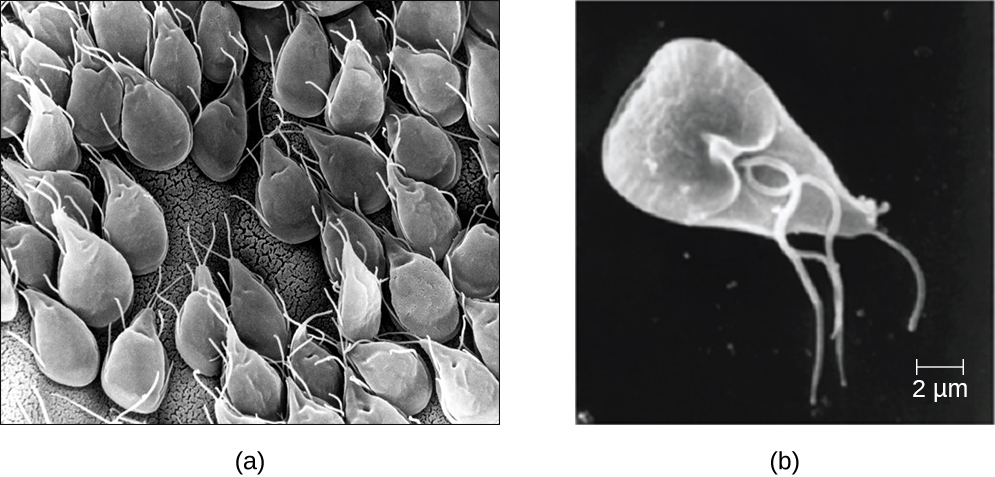

Eukaryotic microbes are an extraordinarily diverse group, including species with a wide range of life cycles, morphological specializations, and nutritional needs. Although more diseases are caused by viruses and bacteria than by microscopic eukaryotes, these eukaryotes are responsible for some diseases of great public health importance. For example, the protozoal disease malaria was responsible for 584,000 deaths worldwide (primarily children in Africa) in 2013, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The protist parasite Giardia causes a diarrheal illness (giardiasis) that is easily transmitted through contaminated water supplies. In the United States, Giardia is the most common human intestinal parasite (Figure 5.2). Although it may seem surprising, parasitic worms are included within the study of microbiology because identification depends on observation of microscopic adult worms or eggs. Even in developed countries, these worms are important parasites of humans and of domestic animals. There are fewer fungal pathogens, but these are important causes of illness, as well. On the other hand, fungi have been important in producing antimicrobial substances such as penicillin. In this chapter, we will examine characteristics of protists, worms, and fungi while considering their roles in causing disease.

Characteristics of Protists

The word protist is a historical term that is now used informally to refer to a diverse group of microscopic eukaryotic organisms. It is not considered a formal taxonomic term because the organisms it describes do not have a shared evolutionary origin. Historically, the protists were informally grouped into the “animal-like” protozoans, the “plant-like” algae, and the “fungus-like” protists such as water molds. These three groups of protists differ greatly in terms of their basic characteristics. For example, algae are photosynthetic organisms that can be unicellular or multicellular. Protozoa, on the other hand, are nonphotosynthetic, motile organisms that are always unicellular. Other informal terms may also be used to describe various groups of protists. For example, microorganisms that drift or float in water, moved by currents, are referred to as plankton. Types of plankton include zooplankton, which are motile and nonphotosynthetic, and phytoplankton, which are photosynthetic.

Protozoans inhabit a wide variety of habitats, both aquatic and terrestrial. Many are free-living, while others are parasitic, carrying out a life cycle within a host or hosts and potentially causing illness. There are also beneficial symbionts that provide metabolic services to their hosts. During the feeding and growth part of their life cycle, they are called trophozoites; these feed on small particulate food sources such as bacteria. While some types of protozoa exist exclusively in the trophozoite form, others can develop from trophozoite to an encapsulated cyst stage when environmental conditions are too harsh for the trophozoite. A cyst is a cell with a protective wall, and the process by which a trophozoite becomes a cyst is called encystment. When conditions become more favorable, these cysts are triggered by environmental cues to become active again through excystment.

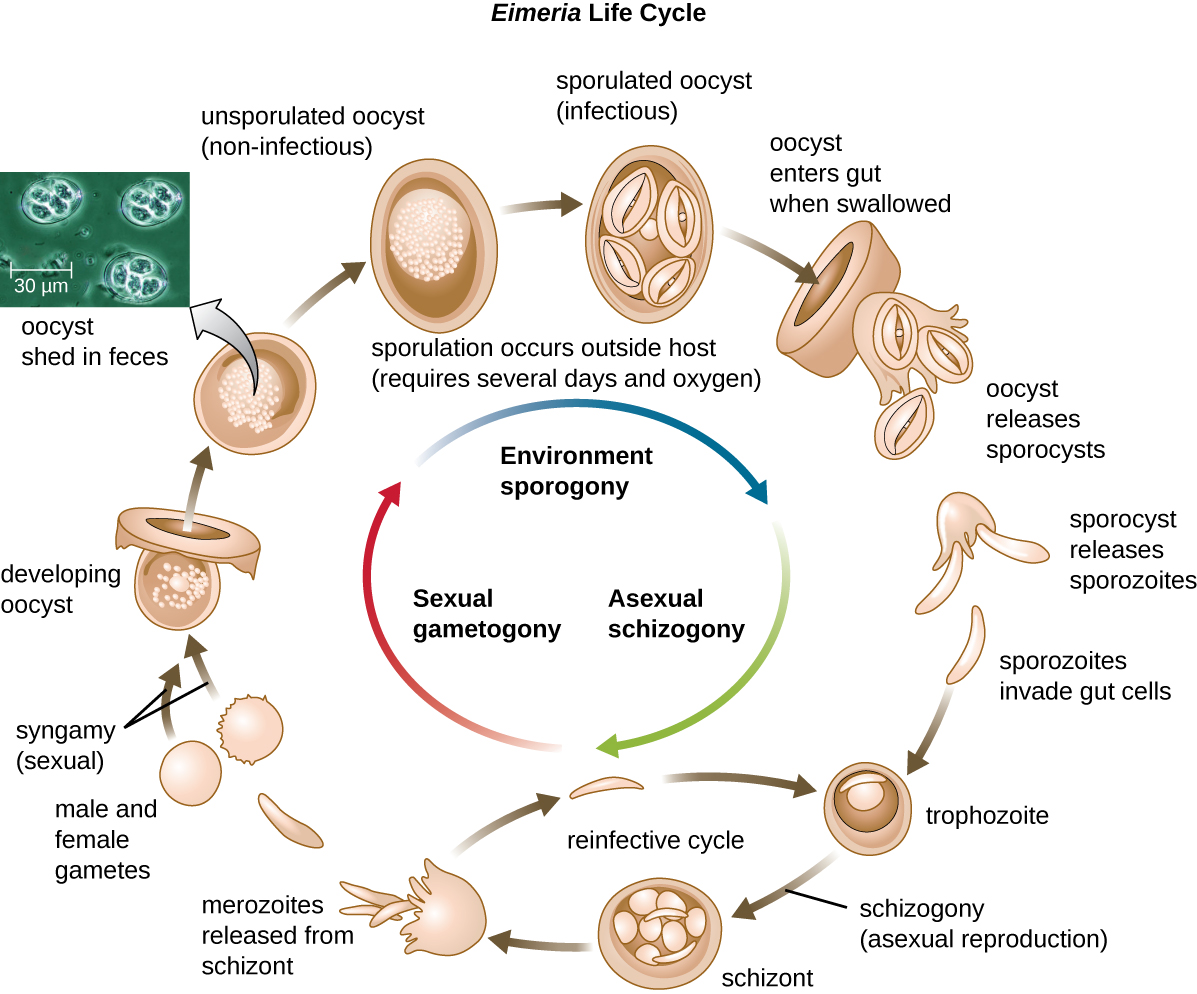

One protozoan genus capable of encystment is Eimeria, which includes some human and animal pathogens. Figure 5.3 illustrates the life cycle of Eimeria.

Protozoans have a variety of reproductive mechanisms. Some protozoans reproduce asexually and others reproduce sexually; still others are capable of both sexual and asexual reproduction. In protozoans, asexual reproduction occurs by binary fission, budding, or schizogony. In schizogony, the nucleus of a cell divides multiple times before the cell divides into many smaller cells. The products of schizogony are called merozoites and they are stored in structures known as schizonts. Protozoans may also reproduce sexually, which increases genetic diversity and can lead to complex life cycles. Protozoans can produce haploid gametes that fuse through syngamy. However, they can also exchange genetic material by joining to exchange DNA in a process called conjugation. This is a different process than the conjugation that occurs in bacteria. The term protist conjugation refers to a true form of eukaryotic sexual reproduction between two cells of different mating types. It is found in ciliates, a group of protozoans, and is described later in this subsection.

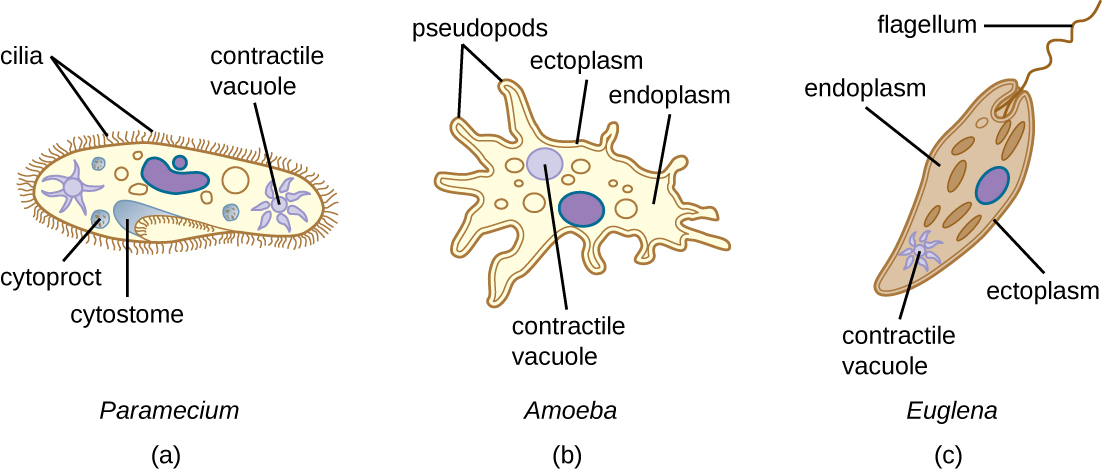

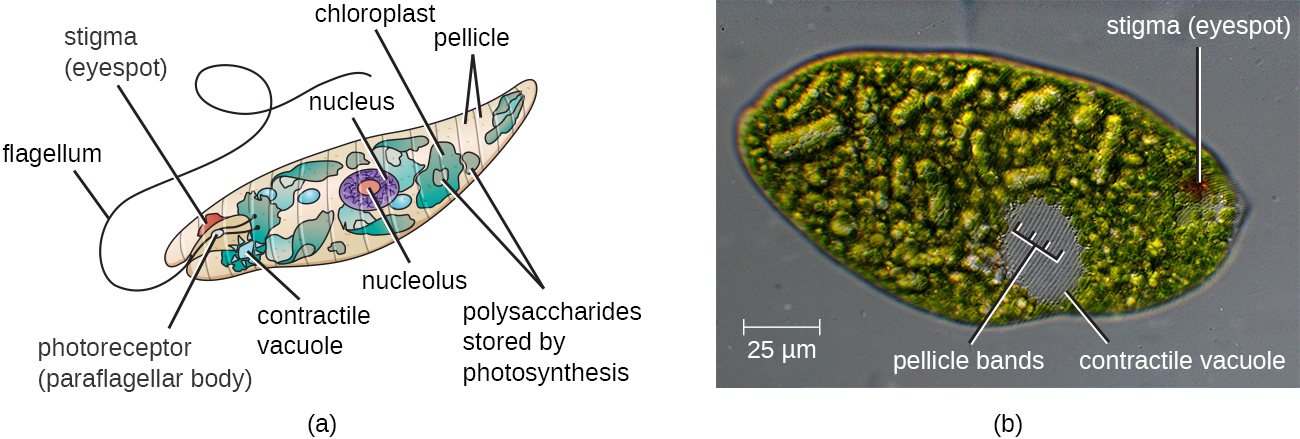

All protozoans have a plasma membrane, or plasmalemma, and some have bands of protein just inside the membrane that add rigidity, forming a structure called the pellicle. Some protists, including protozoans, have distinct layers of cytoplasm under the membrane. In these protists, the outer gel layer (with microfilaments of actin) is called the ectoplasm. Inside this layer is a sol (fluid) region of cytoplasm called the endoplasm. These structures contribute to complex cell shapes in some protozoans, whereas others (such as amoebas) have more flexible shapes (Figure 5.5).

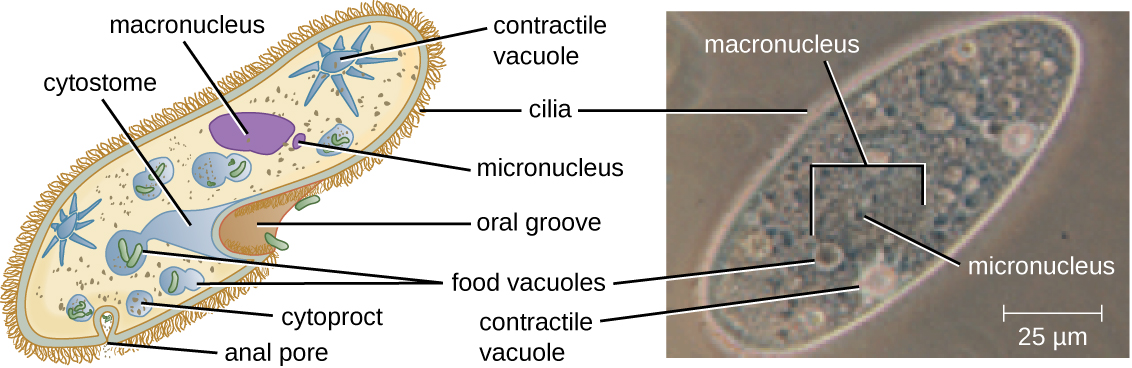

Different groups of protozoans have specialized feeding structures. They may have a specialized structure for taking in food through phagocytosis, called a cytostome, and a specialized structure for the exocytosis of wastes called a cytoproct. Oral grooves leading to cytostomes are lined with hair-like cilia to sweep in food particles. Protozoans are heterotrophic. Protozoans that are holozoic ingest whole food particles through phagocytosis. Forms that are saprozoic ingest small, soluble food molecules.

Many protists have whip-like flagella or hair-like cilia made of microtubules that can be used for locomotion (Figure 5.5). Other protists use cytoplasmic extensions known as pseudopodia (“false feet”) to attach the cell to a surface; they then allow cytoplasm to flow into the extension, thus moving themselves forward.

Protozoans have a variety of unique organelles and sometimes lack organelles found in other cells. Some have contractile vacuoles, organelles that can be used to move water out of the cell for osmotic regulation (salt and water balance) (Figure 5.4). Mitochondria may be absent in parasites or altered to kinetoplastids (modified mitochondria) or hydrogenosomes (see Unique Characteristics of Prokaryotic Cells for more discussion of these structures).

Check Your Understanding

- What is the sequence of events in reproduction by schizogony and what are the cells produced called?

Taxonomy of Protists

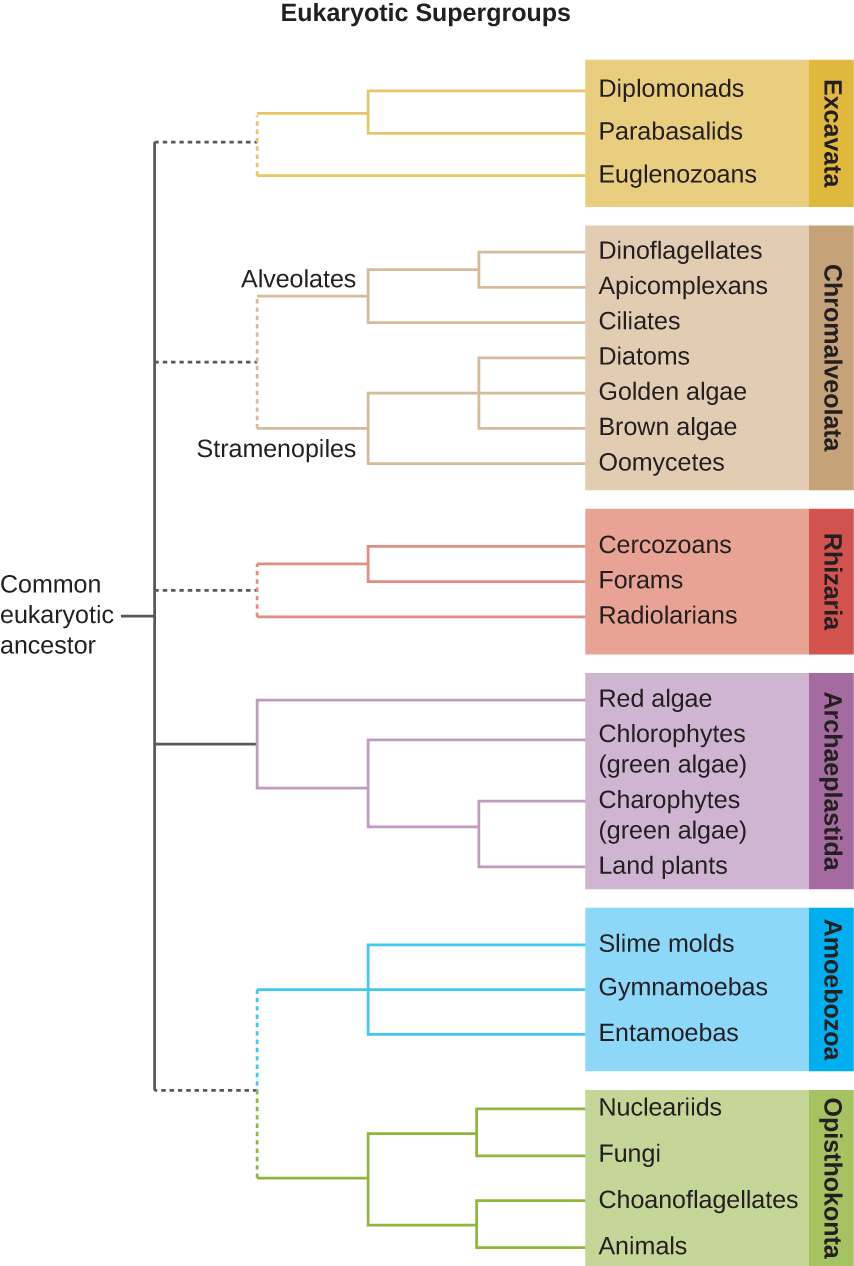

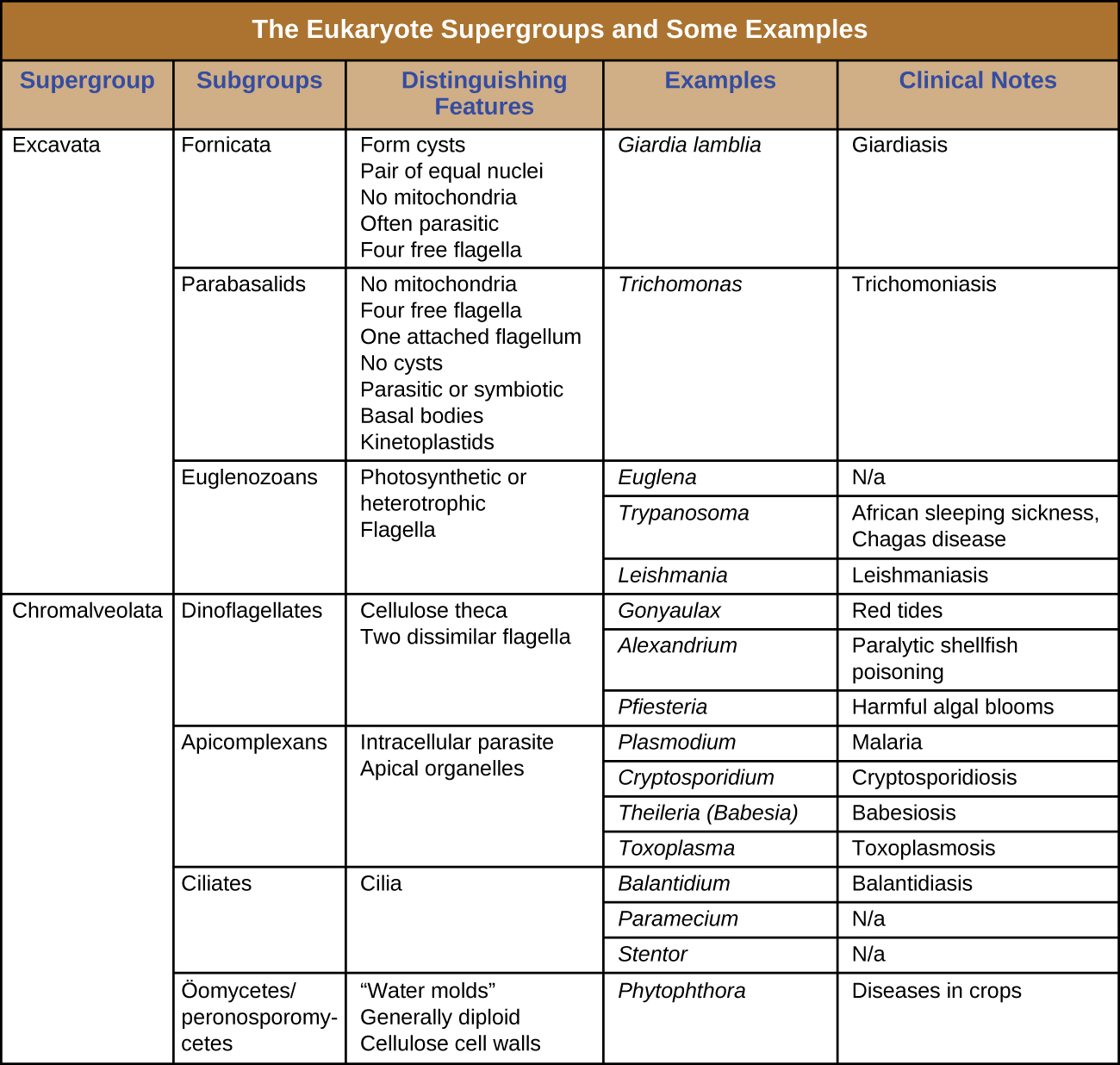

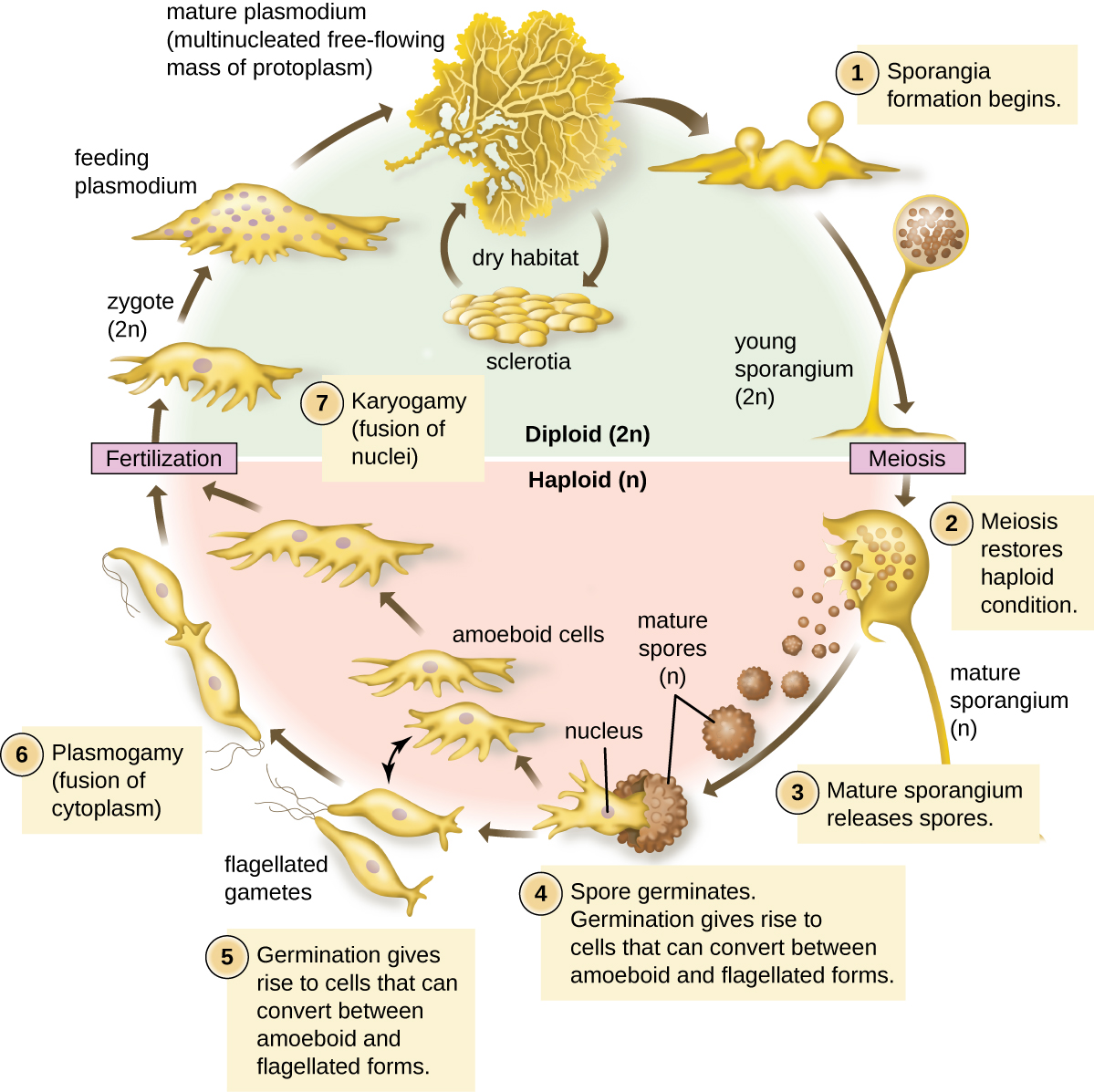

The protists are a polyphyletic group, meaning they lack a shared evolutionary origin. Since the current taxonomy is based on evolutionary history (as determined by biochemistry, morphology, and genetics), protists are scattered across many different taxonomic groups within the domain Eukarya. Eukarya is currently divided into six supergroups that are further divided into subgroups, as illustrated in (Figure 5.5). In this section, we will primarily be concerned with the supergroups Amoebozoa, Excavata, and Chromalveolata; these supergroups include many protozoans of clinical significance. The supergroups Opisthokonta and Rhizaria also include some protozoans, but few of clinical significance. In addition to protozoans, Opisthokonta also includes animals and fungi, some of which we will discuss in Parasitic Helminths and Fungi. Some examples of the Archaeplastida will be discussed in Algae. Figure 5.6 and Figure 5.7 summarize the characteristics of each supergroup and subgroup and list representatives of each.

Check Your Understanding

- Which supergroups contain the clinically significant protists?

Amoebozoa

The supergroup Amoebozoa includes protozoans that use amoeboid movement. Actin microfilaments produce pseudopodia, into which the remainder of the protoplasm flows, thereby moving the organism. The genus Entamoeba includes commensal or parasitic species, including the medically important E. histolytica, which is transmitted by cysts in feces and is the primary cause of amoebic dysentery. The notorious “brain-eating amoeba,” Naegleria fowleri, is also classified within the Amoebozoa. This deadly parasite is found in warm, fresh water and causes primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). Another member of this group is Acanthamoeba, which can cause keratitis (corneal inflammation) and blindness.

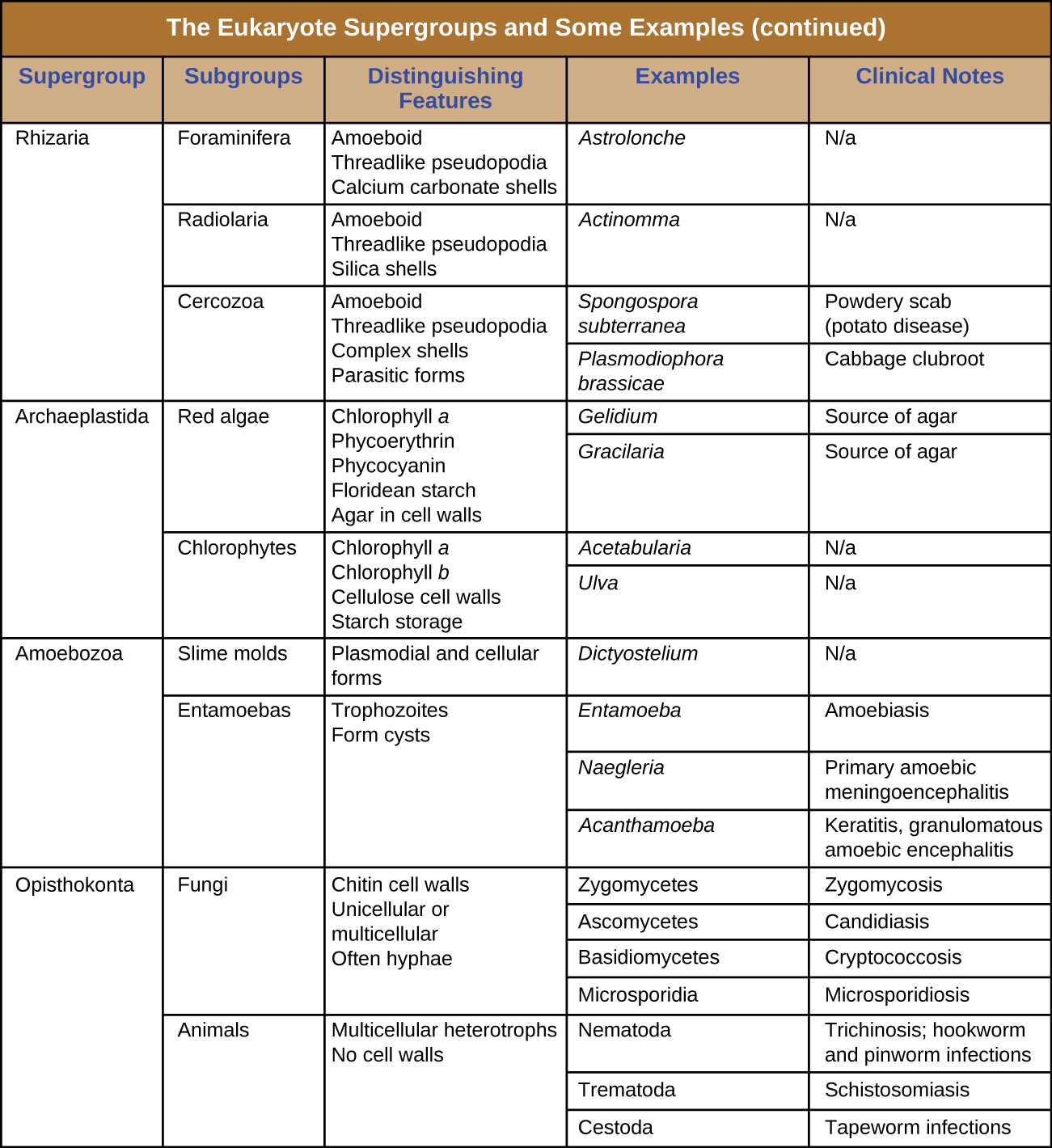

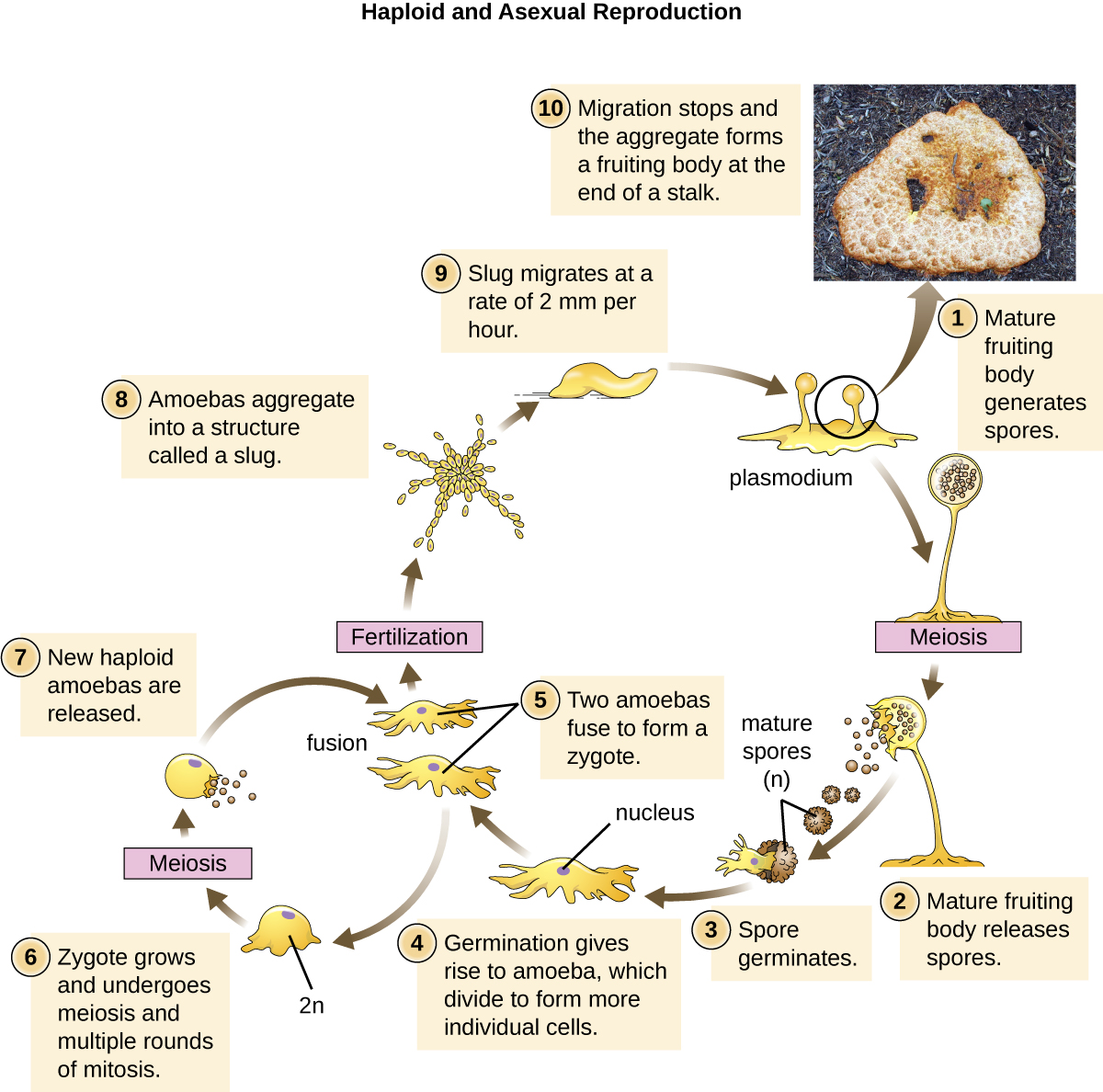

The Eumycetozoa are an unusual group of organisms called slime molds, which have previously been classified as animals, fungi, and plants (Figure 5.8). Slime molds can be divided into two types: cellular slime molds and plasmodial slime molds. The cellular slime molds exist as individual amoeboid cells that periodically aggregate into a mobile slug. The aggregate then forms a fruiting body that produces haploid spores. Plasmodial slime molds exist as large, multinucleate amoeboid cells that form reproductive stalks to produce spores that divide into gametes. One cellular slime mold, Dictyostelium discoideum, has been an important study organism for understanding cell differentiation, because it has both single-celled and multicelled life stages, with the cells showing some degree of differentiation in the multicelled form. Figure 5.9 and Figure 5.10 illustrate the life cycles of cellular and plasmodial slime molds, respectively.

Chromalveolata

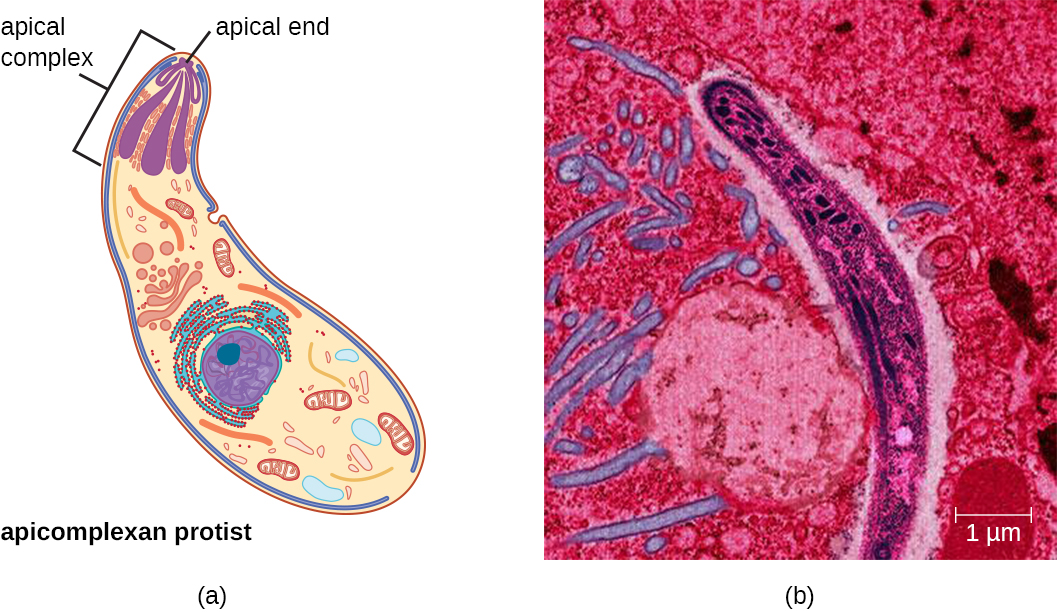

The supergroup Chromalveolata is united by similar origins of its members’ plastids and includes the apicomplexans, ciliates, diatoms, and dinoflagellates, among other groups (we will cover the diatoms and dinoflagellates in Algae). The apicomplexans are intra- or extracellular parasites that have an apical complex at one end of the cell. The apical complex is a concentration of organelles, vacuoles, and microtubules that allows the parasite to enter host cells (Figure 5.11). Apicomplexans have complex life cycles that include an infective sporozoite that undergoes schizogony to make many merozoites (see the example in Figure 5.5). Many are capable of infecting a variety of animal cells, from insects to livestock to humans, and their life cycles often depend on transmission between multiple hosts. The genus Plasmodium is an example of this group.

Other apicomplexans are also medically important. Cryptosporidium parvum causes intestinal symptoms and can cause epidemic diarrhea when the cysts contaminate drinking water. Theileria (Babesia) microti, transmitted by the tick Ixodes scapularis, causes recurring fever that can be fatal and is becoming a common transfusion-transmitted pathogen in the United States (Theileria and Babesia are closely related genera and there is some debate about the best classification). Finally, Toxoplasma gondii causes toxoplasmosis and can be transmitted from cat feces, unwashed fruit and vegetables, or from undercooked meat. Because toxoplasmosis can be associated with serious birth defects, pregnant women need to be aware of this risk and use caution if they are exposed to the feces of potentially infected cats. A national survey found the frequency of individuals with antibodies for toxoplasmosis (and thus who presumably have a current latent infection) in the United States to be 11%. Rates are much higher in other countries, including some developed countries.3 There is also evidence and a good deal of theorizing that the parasite may be responsible for altering infected humans’ behavior and personality traits.4

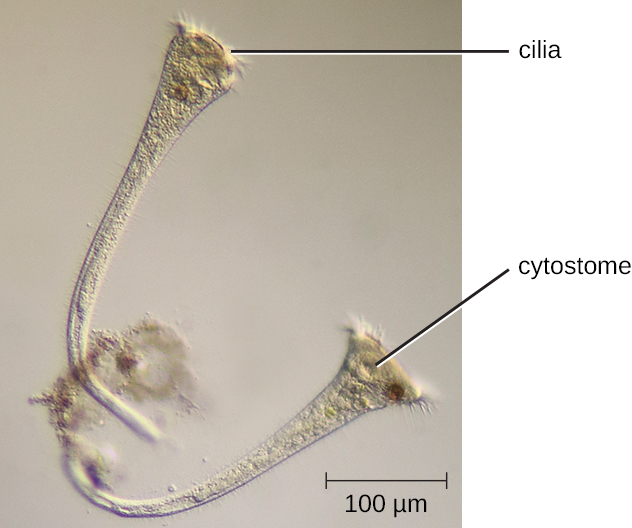

The ciliates (Ciliaphora), also within the Chromalveolata, are a large, very diverse group characterized by the presence of cilia on their cell surface. Although the cilia may be used for locomotion, they are often used for feeding, as well, and some forms are nonmotile. Balantidium coli (Figure 5.13) is the only parasitic ciliate that affects humans by causing intestinal illness, although it rarely causes serious medical issues except in the immunocompromised (those having a weakened immune system). Perhaps the most familiar ciliate is Paramecium, a motile organism with a clearly visible cytostome and cytoproct that is often studied in biology laboratories (Figure 5.12). Another ciliate, Stentor, is sessile and uses its cilia for feeding (Figure 5.15). Generally, these organisms have a micronucleus that is diploid, somatic, and used for sexual reproduction by conjugation. They also have a macronucleus that is derived from the micronucleus; the macronucleus becomes polyploid (multiple sets of duplicate chromosomes), and has a reduced set of metabolic genes.

Ciliates are able to reproduce through conjugation, in which two cells attach to each other. In each cell, the diploid micronuclei undergo meiosis, producing eight haploid nuclei each. Then, all but one of the haploid micronuclei and the macronucleus disintegrate; the remaining (haploid) micronucleus undergoes mitosis. The two cells then exchange one micronucleus each, which fuses with the remaining micronucleus present to form a new, genetically different, diploid micronucleus. The diploid micronucleus undergoes two mitotic divisions, so each cell has four micronuclei, and two of the four combine to form a new macronucleus. The chromosomes in the macronucleus then replicate repeatedly, the macronucleus reaches its polyploid state, and the two cells separate. The two cells are now genetically different from each other and from their previous versions.

Öomycetes have similarities to fungi and were once classified with them. They are also called water molds. However, they differ from fungi in several important ways. Öomycetes have cell walls of cellulose (unlike the chitinous cell walls of fungi) and they are generally diploid, whereas the dominant life forms of fungi are typically haploid. Phytophthora, the plant pathogen found in the soil that caused the Irish potato famine, is classified within this group (Figure 5.15).

Link to Learning

Excavata

The third and final supergroup to be considered in this section is the Excavata, which includes primitive eukaryotes and many parasites with limited metabolic abilities. These organisms have complex cell shapes and structures, often including a depression on the surface of the cell called an excavate. The group Excavata includes the subgroups Fornicata, Parabasalia, and Euglenozoa. The Fornicata lack mitochondria but have flagella. This group includes Giardia lamblia (also known as G. intestinalis or G. duodenalis), a widespread pathogen that causes diarrheal illness and can be spread through cysts from feces that contaminate water supplies (Figure 5.3). Parabasalia are frequent animal endosymbionts; they live in the guts of animals like termites and cockroaches. They have basal bodies and modified mitochondria (kinetoplastids). They also have a large, complex cell structure with an undulating membrane and often have many flagella. The trichomonads (a subgroup of the Parabasalia) include pathogens such as Trichomonas vaginalis, which causes the human sexually transmitted disease trichomoniasis. Trichomoniasis often does not cause symptoms in men, but men are able to transmit the infection. In women, it causes vaginal discomfort and discharge and may cause complications in pregnancy if left untreated.

The Euglenozoa are common in the environment and include photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic species. Members of the genus Euglena are typically not pathogenic. Their cells have two flagella, a pellicle, a stigma (eyespot) to sense light, and chloroplasts for photosynthesis (Figure 5.16). The pellicle of Euglena is made of a series of protein bands surrounding the cell; it supports the cell membrane and gives the cell shape.

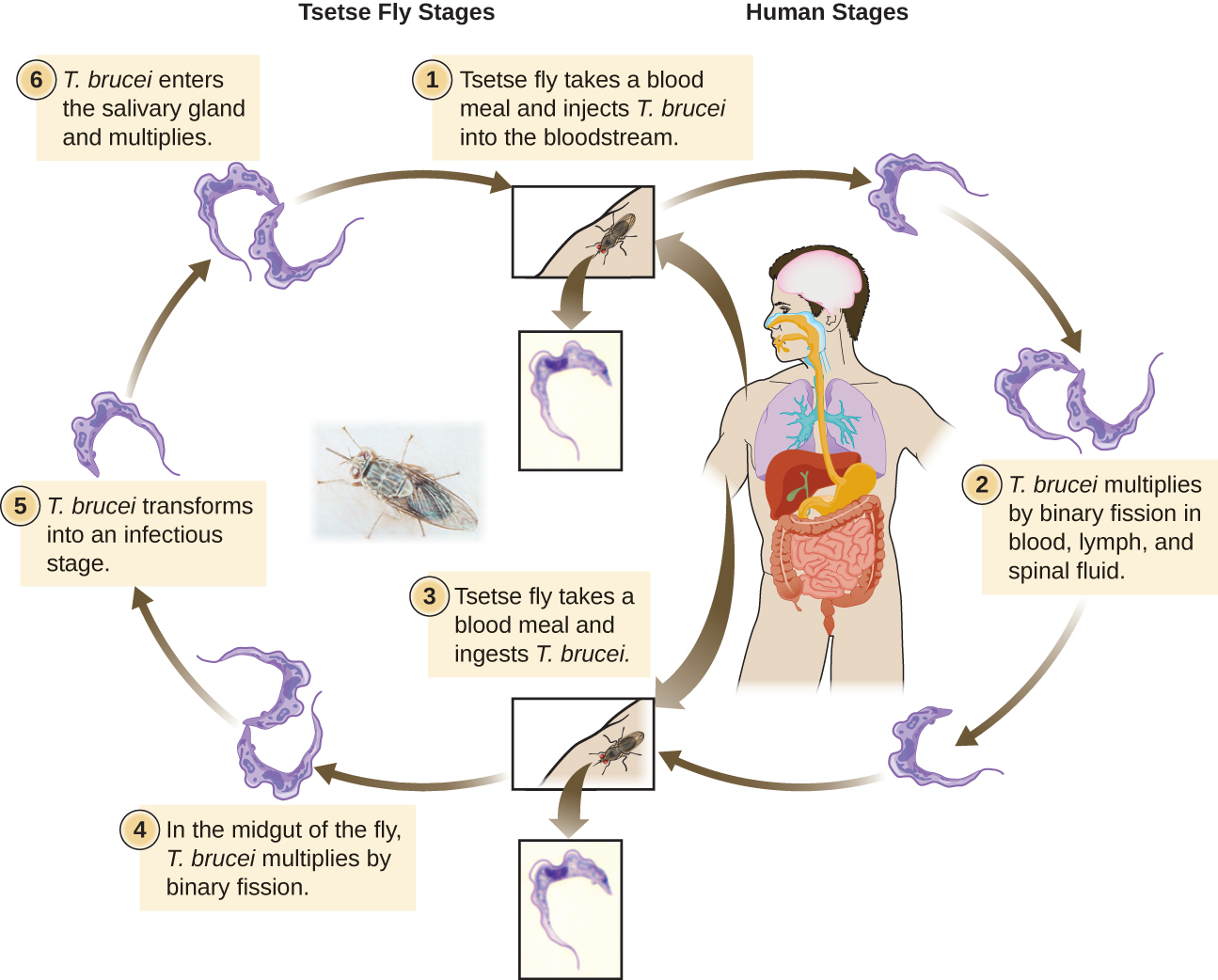

The Euglenozoa also include the trypanosomes, which are parasitic pathogens. The genus Trypanosoma includes T. brucei, which causes African trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness and T. cruzi, which causes American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease). These tropical diseases are spread by insect bites. In African sleeping sickness, T. brucei colonizes the blood and the brain after being transmitted via the bite of a tsetse fly (Glossina spp.) (Figure 5.17). The early symptoms include confusion, difficulty sleeping, and lack of coordination. Left untreated, it is fatal.

Chagas’ disease originated and is most common in Latin America. The disease is transmitted by Triatoma spp., insects often called “kissing bugs,” and affects either the heart tissue or tissues of the digestive system. Untreated cases can eventually lead to heart failure or significant digestive or neurological disorders.

The genus Leishmania includes trypanosomes that cause disfiguring skin disease and sometimes systemic illness as well.

Eye on Ethics

Neglected Parasites

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is responsible for identifying public health priorities in the United States and developing strategies to address areas of concern. As part of this mandate, the CDC has officially identified five parasitic diseases it considers to have been neglected (i.e., not adequately studied). These neglected parasitic infections (NPIs) include toxoplasmosis, Chagas disease, toxocariasis (a nematode infection transmitted primarily by infected dogs), cysticercosis (a disease caused by a tissue infection of the tapeworm Taenia solium), and trichomoniasis (a sexually transmitted disease caused by the parabasalid Trichomonas vaginalis).

The decision to name these specific diseases as NPIs means that the CDC will devote resources toward improving awareness and developing better diagnostic testing and treatment through studies of available data. The CDC may also advise on treatment of these diseases and assist in the distribution of medications that might otherwise be difficult to obtain.5

Of course, the CDC does not have unlimited resources, so by prioritizing these five diseases, it is effectively deprioritizing others. Given that many Americans have never heard of many of these NPIs, it is fair to ask what criteria the CDC used in prioritizing diseases. According to the CDC, the factors considered were the number of people infected, the severity of the illness, and whether the illness can be treated or prevented. Although several of these NPIs may seem to be more common outside the United States, the CDC argues that many cases in the United States likely go undiagnosed and untreated because so little is known about these diseases.6

What criteria should be considered when prioritizing diseases for purposes of funding or research? Are those identified by the CDC reasonable? What other factors could be considered? Should government agencies like the CDC have the same criteria as private pharmaceutical research labs? What are the ethical implications of deprioritizing other potentially neglected parasitic diseases such as leishmaniasis?

Footnotes

J. Flegr et al. “Toxoplasmosis—A Global Threat. Correlation of Latent Toxoplasmosis With Specific Disease Burden in a Set of 88 Countries.” PloS ONE 9 no. 3 (2014):e90203.

J. Flegr. “Effects of Toxoplasma on Human Behavior.” Schizophrenia Bull 33, no. 3 (2007):757–760.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Neglected Parasitic Infections (NPIs) in the United States.” http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/npi/. Last updated July 10, 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Fact Sheet: Neglected Parasitic Infections in the United States.” http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/resources/pdf/npi_factsheet.pdf