7.5 – Using Biochemistry to Identify Microorganisms

Learning Objectives

- Describe examples of biosynthesis products within a cell that can be detected to identify bacteria

Accurate identification of bacterial isolates is essential in a clinical microbiology laboratory because the results often inform decisions about treatment that directly affect patient outcomes. For example, cases of food poisoning require accurate identification of the causative agent so that physicians can prescribe appropriate treatment. Likewise, it is important to accurately identify the causative pathogen during an outbreak of disease so that appropriate strategies can be employed to contain the epidemic.

There are many ways to detect, characterize, and identify microorganisms. Some methods rely on phenotypic biochemical characteristics, while others use genotypic identification. The biochemical characteristics of a bacterium provide many traits that are useful for classification and identification. Analyzing the nutritional and metabolic capabilities of the bacterial isolate is a common approach for determining the genus and the species of the bacterium. Some of the most important metabolic pathways that bacteria use to survive will be discussed in Microbial Metabolism. In this section, we will discuss a few methods that use biochemical characteristics to identify microorganisms.

Some microorganisms store certain compounds as granules within their cytoplasm, and the contents of these granules can be used for identification purposes. For example, poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) is a carbon- and energy-storage compound found in some nonfluorescent bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas. Different species within this genus can be classified by the presence or the absence of PHB and fluorescent pigments. The human pathogen P. aeruginosa and the plant pathogen P. syringae are two examples of fluorescent Pseudomonas species that do not accumulate PHB granules.

Other systems rely on biochemical characteristics to identify microorganisms by their biochemical reactions, such as carbon utilization and other metabolic tests. In small laboratory settings or in teaching laboratories, those assays are carried out using a limited number of test tubes. However, more modern systems, such as the one developed by Biolog, Inc., are based on panels of biochemical reactions performed simultaneously and analyzed by software. Biolog’s system identifies cells based on their ability to metabolize certain biochemicals and on their physiological properties, including pH and chemical sensitivity. It uses all major classes of biochemicals in its analysis. Identifications can be performed manually or with the semi- or fully automated instruments.

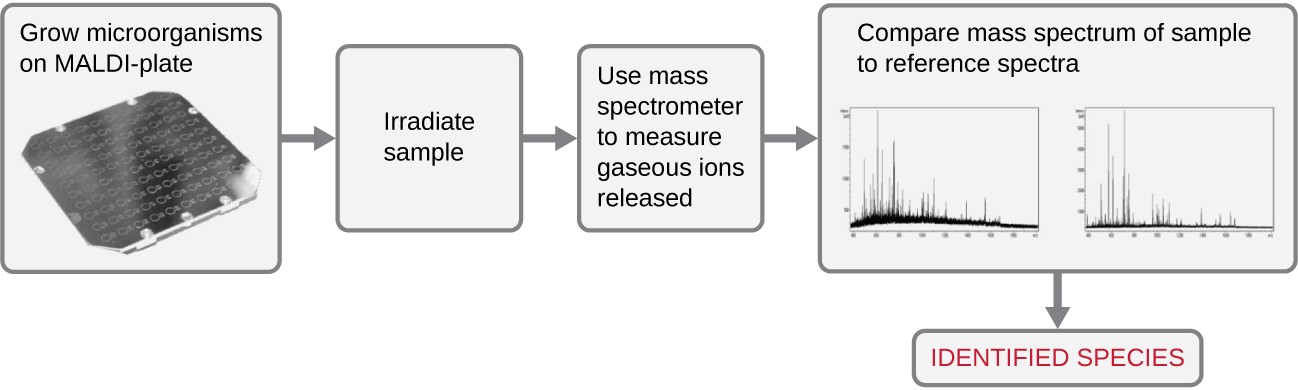

Another automated system identifies microorganisms by determining the specimen’s mass spectrum and then comparing it to a database that contains known mass spectra for thousands of microorganisms. This method is based on matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) and uses disposable MALDI plates on which the microorganism is mixed with a specialized matrix reagent (Figure 7.26). The sample/ reagent mixture is irradiated with a high-intensity pulsed ultraviolet laser, resulting in the ejection of gaseous ions generated from the various chemical constituents of the microorganism. These gaseous ions are collected and accelerated through the mass spectrometer, with ions traveling at a velocity determined by their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), thus, reaching the detector at different times. A plot of detector signal versus m/z yields a mass spectrum for the organism that is uniquely related to its biochemical composition. Comparison of the mass spectrum to a library of reference spectra obtained from identical analyses of known microorganisms permits identification of the unknown microbe.

Steps include 1. Grow microorganisms on MALDI plate 2. Irradiate sample 3. Use mass spectrometer to measure gaseous ions released 4. Compare mass spectrum of sample to reference spectra 5. Identify species

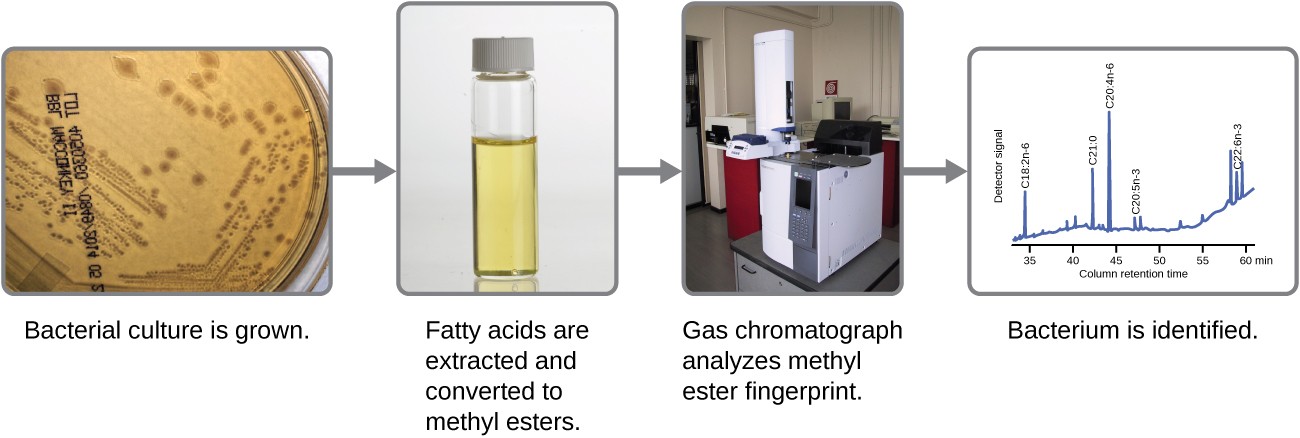

Microbes can also be identified by measuring their unique lipid profiles. As we have learned, fatty acids of lipids can vary in chain length, presence or absence of double bonds, and number of double bonds, hydroxyl groups, branches, and rings. To identify a microbe by its lipid composition, the fatty acids present in their membranes are analyzed. A common biochemical analysis used for this purpose is a technique used in clinical, public health, and food laboratories. It relies on detecting unique differences in fatty acids and is called fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) analysis. In a FAME analysis, fatty acids are extracted from the membranes of microorganisms, chemically altered to form volatile methyl esters, and analyzed by gas chromatography (GC). The resulting GC chromatogram is compared with reference chromatograms in a database containing data for thousands of bacterial isolates to identify the unknown microorganism (Figure 7.27).

steps in the fatty acis methyl ester (FAME) analysis: 1. Bacterial culture is grown. 2. Fatty acids are extracted and converted to methyl esters. 3. Gas chromatograph analyzes methyl ester fingerprint. 4. Bacterium is identified.

A related method for microorganism identification is called phospholipid-derived fatty acids (PLFA) analysis. Membranes are mostly composed of phospholipids, which can be saponified (hydrolyzed with alkali) to release the fatty acids. The resulting fatty acid mixture is then subjected to FAME analysis, and the measured lipid profiles can be compared with those of known microorganisms to identify the unknown microorganism.

Bacterial identification can also be based on the proteins produced under specific growth conditions within the human body. These types of identification procedures are called proteomic analysis. To perform proteomic analysis, proteins from the pathogen are first separated by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), and the collected fractions are then digested to yield smaller peptide fragments. These peptides are identified by mass spectrometry and compared with those of known microorganisms to identify the unknown microorganism in the original specimen.

Microorganisms can also be identified by the carbohydrates attached to proteins (glycoproteins) in the plasma membrane or cell wall. Antibodies and other carbohydrate-binding proteins can attach to specific carbohydrates on cell surfaces, causing the cells to clump together. Serological tests (e.g., the Lancefield groups tests, which are used for identification of Streptococcus species) are performed to detect the unique carbohydrates located on the surface of the cell.