12 Problems with the Public Sector

12.1 The design of a tax system

Equity and Taxes

Vertical and Horizontal Equity

From: Wikipedia: Equity (economics)

In public finance, vertical equity is the idea that people with a similar ability to pay taxes should pay the same or similar amounts. It is related to the concept of tax neutrality or the idea that the tax system should not discriminate between similar things or people, or unduly distort behavior.[3]

Vertical equity usually refers to the idea that people with a greater ability to pay taxes should pay more. If the rich pay more in proportion to their income, this is known as a proportional tax; if they pay an increasing proportion, this is termed a progressive tax, sometimes associated with redistribution of wealth.[4]

From: Wikipedia: Horizontal inequality

Horizontal inequality is the inequality—economical, social or other—that does not follow from a difference in an inherent quality such as intelligence, attractiveness or skills for people or profitability for corporations. In sociology, this is particularly applicable to forced inequality between different subcultures living in the same society, i.e inequalities between culturally formed groups, not economically formed ones[1].

In economics, horizontal inequality is seen when people of similar origin, intelligence, etc. still do not have equal success and have different status, income and wealth.

Traditional economic theory predicts that horizontal inequality should not exist in a free market. However, horizontal inequality is observed in real and simulated ‘free market’ systems.

Benefit Principle versus Ability to Pay Principle

From: Wikipedia: Benefit principle

The benefit principle is a concept in the theory of taxation from public finance. It bases taxes to pay for public-goods expenditures on a politically-revealed willingness to pay for benefits received. The principle is sometimes likened to the function of prices in allocating private goods.[1] In its use for assessing the efficiency of taxes and appraising fiscal policy.

The benefit principle takes a market-oriented approach to taxation. The objective is to accurately determine the optimal amount of revenue that should be spent on public goods.

- More equitable/fair because taxpayers, like consumers, would “pay for what they get”

- Taxes are more akin to prices that people would pay for government services

- Consumer sovereignty – specific rather than general…charges are more direct…so the preferences of taxpayers, rather than government planners, are given more weight

- More efficient allocation of limited resources…it is less likely that funds will be overinvested in low priority programs.

- There’s no such thing as a free lunch – taxpayers would have a better understanding of the costs of public goods

- Provides the foundation for voluntary exchange theory.

From: Wikipedia: Theories of taxation

The ability-to-pay approach treats government revenue and expenditures separately. Taxes are based on taxpayers’ ability to pay; there is no quid pro quo. Taxes paid are seen as a sacrifice by taxpayers, which raises the issues of what the sacrifice of each taxpayer should be and how it should be measured:

- Equal sacrifice: The total loss of utility as a result of taxation should be equal for all taxpayers (the rich will be taxed more heavily than the poor)

- Equal proportional sacrifice: The proportional loss of utility as a result of taxation should be equal for all taxpayers

- Equal marginal sacrifice: The instantaneous loss of utility (as measured by the derivative of the utility function) as a result of taxation should be equal for all taxpayers. This therefore will entail the least aggregate sacrifice (the total sacrifice will be the least).

The Cost of a Tax System

The Cost to Taxpayers

Taxpayers face costs in three distinct areas:

- The tax payment itself. This one is simple, when you pay tax, you are incurring a cost because you are giving your money to another entity.

- Deadweight loss. Taxpayers may make decisions based on the tax implications. For example, lower income earners may avoid taking a job because of the loss of other government benefits. Not taking a job can have long-term negative implications for the job-seekers, but makes sense in the short-run.

- Administrative cost. Paying taxes takes some work. In the United States, April 15th is a memorable day because it is the day that federal income taxes (and most state and local income taxes) are due. Tax payers have three and a half months to collect all pertinent tax forms and to complete their returns. The paying of taxes requires record keeping and potentially the use of software to correctly pay taxes.

The Cost to the Government

While the government generates revenue from the collection of taxes, there are still costs that must be paid to collect said taxes.

- Tax collection. The government needs some system to collect taxes. For example, in the United States the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) handles the collection of all federal income taxes (in addition to others.) The operation of the IRS comes at a cost. The IRS also must expend resources to stop evasion which is the act of not paying taxes.

- Tax lawyers. The IRS must expend resources to investigate tax avoidance. Tax avoidance is different from tax evasion. Tax evasion is not paying the taxes you owe. On the other hand, tax avoidance is the use of tax law and loopholes in tax law to avoid paying as much in tax. Tax evasion is illegal while tax avoidance, if done properly, is legal. The IRS must use resources to investigate whether the tax avoidance is being done legally or whether the taxpayer owes additional money.

- Deadweight loss. As mentioned above, changes to the economy also affect the government.

Tax Terminology

From: Wikipedia: Tax rate

Statutory tax rate

the legally imposed rate. An income tax could have multiple statutory rates for different income levels, where a sales tax may have a flat statutory rate.[1] The statutory tax rate is expressed as a percentage and will always be higher than the effective tax rate.[2]

Average tax rate

An average tax rate is the ratio of the total amount of taxes paid to the total tax base (taxable income or spending), expressed as a percentage.[1] If t is the total tax paid and i is the total tax base (income), then the average tax rate is just t/i.

In a proportional tax, the tax rate is fixed and the average tax rate equals this tax rate. In case of tax brackets, commonly used for progressive taxes, the average tax rate increases as taxable income increases through tax brackets, asymptoting to the top tax rate. For example, consider a system with three tax brackets, 10%, 20%, and 30%, where the 10% rate applies to income from $1 to $10,000, the 20% rate applies to income from $10,001 to $20,000, and the 30% rate applies to all income above $20,000. Under this system, someone earning $25,000 would pay $1,000 for the first $10,000 of income (10%); $2,000 for the second $10,000 of income (20%); and $1,500 for the last $5,000 of income (30%). In total, they would pay $4,500, or an 18% average tax rate.

Marginal tax rate

A marginal tax rate is the tax rate on income set at a higher rate for incomes above a designated higher bracket, which in 2016 in the United States was $415,050. For annual income that was above cut off point in that higher bracket, the marginal tax rate in 2016 was 39.6%. For income below the $415,050 cut off, the lower tax rate was 35% or less.

Marginal tax rates are applied to income in countries with progressive taxation schemes, with incremental increases in income taxed in progressively higher tax brackets.

In economics, one theory is that marginal tax rates will impact the incentive of increased income, meaning that higher marginal tax rates cause individuals to have less incentive to earn more.

With a flat tax, by comparison, all income is taxed at the same percentage, regardless of amount. An example is a sales tax where all purchases are taxed equally. A poll tax is a flat tax of a set dollar amount per person. The marginal tax in these scenarios would be zero.

Types of Taxes

Progressive Taxes

From: Wikipedia: Progressive tax

A progressive tax is a tax in which the average tax rate (taxes paid ÷ personal income) increases as the taxable amount increases.[1][2][3][4][5] The term “progressive” refers to the way the tax rate progresses from low to high, with the result that a taxpayer’s average tax rate is less than the person’s marginal tax rate.[6][7] The term can be applied to individual taxes or to a tax system as a whole; a year, multi-year, or lifetime. Progressive taxes are imposed in an attempt to reduce the tax incidence of people with a lower ability to pay, as such taxes shift the incidence increasingly to those with a higher ability-to-pay. The opposite of a progressive tax is a regressive tax, where the average tax rate or burden decreases as an individual’s ability to pay increases.[5]

The term is frequently applied in reference to personal income taxes, in which people with lower income pay a lower percentage of that income in tax than do those with higher income. It can also apply to adjustments of the tax base by using tax exemptions, tax credits, or selective taxation that creates progressive distribution effects. For example, a wealth or property tax,[8] a sales tax on luxury goods, or the exemption of sales taxes on basic necessities, may be described as having progressive effects as it increases the tax burden of higher income families and reduces it on lower income families.[9][10][11]

Progressive taxation is often suggested as a way to mitigate the societal ills associated with higher income inequality,[12] as the tax structure reduces inequality,[13] but economists disagree on the tax policy’s economic and long-term effects.[14][15][16] One study suggests progressive taxation can be positively associated with happiness, the subjective well-being of nations and citizen satisfaction with public goods, such as education and transportation.[17]

Flat Tax

From: Wikipedia: Flat tax

A flat tax (short for flat-rate tax) is a tax system with a constant marginal rate, usually applied to individual or corporate income. A true flat tax would be a proportional tax, but implementations are often progressive and sometimes regressive depending on deductions and exemptions in the tax base. There are various tax systems that are labeled “flat tax” even though they are significantly different.

A true flat-rate tax is a system of taxation where one tax rate is applied to all personal income with no deductions. This is also called a proportional tax.

Regressive Tax

From: Wikipedia: Regressive tax

A regressive tax is a tax imposed in such a manner that the average tax rate (tax paid ÷ personal income) decreases as the amount subject to taxation increases.[1][2][3][4][5] “Regressive” describes a distribution effect on income or expenditure, referring to the way the rate progresses from high to low, so that the average tax rate exceeds the marginal tax rate.[6][7] In terms of individual income and wealth, a regressive tax imposes a greater burden (relative to resources) on the poor than on the rich: there is an inverse relationship between the tax rate and the taxpayer’s ability to pay, as measured by assets, consumption, or income. These taxes tend to reduce the tax burden of the people with a higher ability to pay, as they shift the relative burden increasingly to those with a lower ability to pay.

The regressivity of a particular tax can also factor the propensity of the taxpayers to engage in the taxed activity relative to their resources (the demographics of the tax base). In other words, if the activity being taxed is more likely to be carried out by the poor and less likely to be carried out by the rich, the tax may be considered regressive.[8]

Poll Tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual.[1]

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments from ancient times until the 19th century. In the United Kingdom, poll taxes were levied by the governments of John of Gaunt in the 14th century, Charles II in the 17th and Margaret Thatcher in the 20th century. In the United States, voting poll taxes have been used to disenfranchise impoverished and minority voters (especially under Reconstruction).[2]

Poll taxes are considered very regressive taxes, and are usually very unpopular and have been implicated in many uprisings.

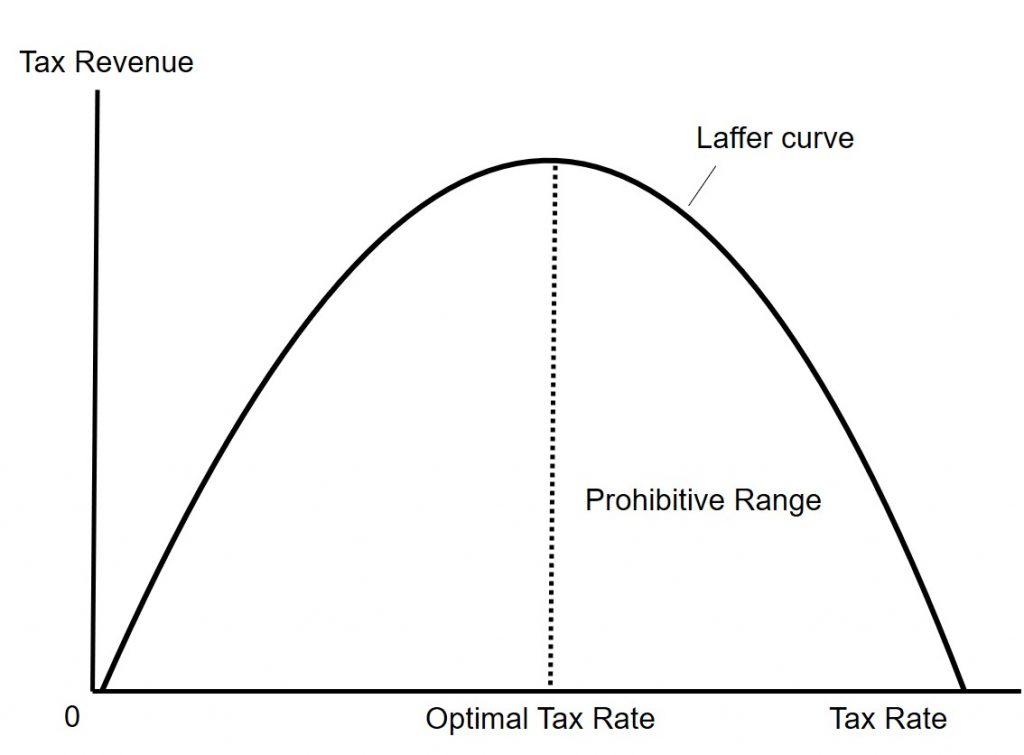

The Laffer Curve

From: Wikipedia: Laffer curve

In economics, the Laffer curve illustrates a theoretical relationship between rates of taxation and the resulting levels of government revenue. It illustrates the concept of taxable income elasticity—i.e., taxable income changes in response to changes in the rate of taxation. The Laffer curve assumes that no tax revenue is raised at the extreme tax rates of 0% and 100%, and that there is a rate between 0% and 100% that maximizes government taxation revenue. The Laffer curve is typically represented as a graph that starts at 0% tax with zero revenue, rises to a maximum rate of revenue at an intermediate rate of taxation, and then falls again to zero revenue at a 100% tax rate. However, the shape of the curve is uncertain and disputed among economists. A graphical representation of a “basic” Laffer Curve is presented below.

One implication of the Laffer curve is that reducing or increasing tax rates beyond a certain point is counter-productive for raising further tax revenue. A hypothetical Laffer curve for any given economy can only be estimated and such estimates are controversial. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics reports that estimates of revenue-maximizing tax rates have varied widely, with a mid-range of around 70%.[4] There is a consensus among leading economists that a reduction in the US federal income tax rate would not raise annual total tax revenue.[5]

12.2 The role of the government

To this point, we have discussed some of the following roles of the government:

- Regulation/taxation of goods which emit a negative externality

- Providing/subsidizing goods which emit a positive externality

- Free rider problem

- Provision of information

- Fraud prevention

We will discuss several more below.

Rights

From: Wikipedia: Rights

In one sense, a right is a permission to do something or an entitlement to a specific service or treatment from others, and these rights have been called positive rights. However, in another sense, rights may allow or require inaction, and these are called negative rights; they permit or require doing nothing. For example, in some countries, e.g. the United States, citizens have the positive right to vote and they have the negative right to not vote; people can choose not to vote in a given election without punishment. In other countries, e.g. Australia, however, citizens have a positive right to vote but they don’t have a negative right to not vote, since voting is compulsory. Accordingly:

- Positive rights are permissions to do things, or entitlements to be done unto. One example of a positive right is the purported “right to welfare.”[4]

- Negative rights are permissions not to do things, or entitlements to be left alone. Often the distinction is invoked by libertarians who think of a negative right as an entitlement to non-interference such as a right against being assaulted.[4]

Though similarly named, positive and negative rights should not be confused with active rights (which encompass “privileges” and “powers”) and passive rights (which encompass “claims” and “immunities”).

For example, consider the United States Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution:

- Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

- A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

- No soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

- The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

- No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

- In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

- In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

- Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

- The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

- The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

If you browse through them, you realize that these are all negative rights. Simply put, as long as the government does not forbid the activity, the rights are upheld. For example, as long as the government does not prevent you from speaking (or jail you for speaking), your right to free speech is upheld. The government does not need to do anything to provide this right to you. On the other hand, consider the proposed Second Bill of Rights which was authored by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (from: Wikipedia: Second Bill of Rights )

- The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

- The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

- The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

- The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

- The right of every family to a decent home;

- The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

- The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

- The right to a good education.

Notice that all of these are positive rights. For example, consider the right of every family to a decent home. If a family does not have a decent home, who provides it? In this case, the government must provide a house to those without it. If the government does not act, then the right is not upheld.

12.3 growth of government

Government Expenditures

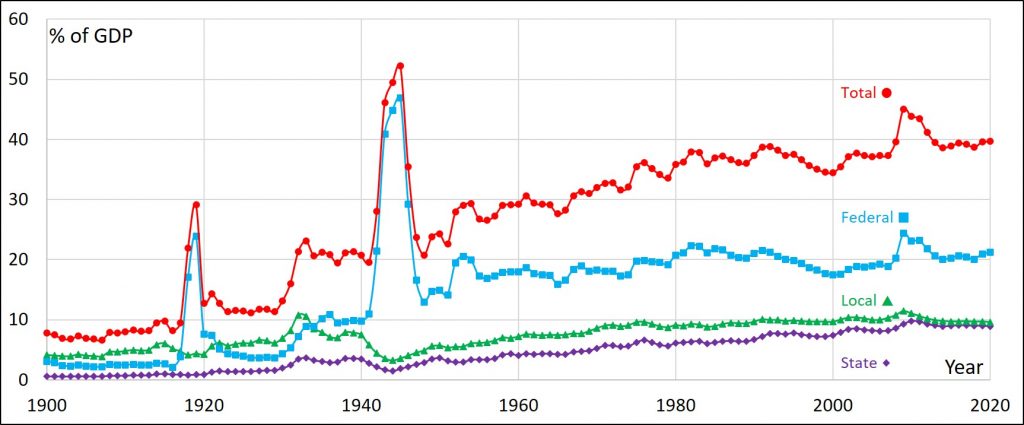

This section will outline how much money is spent by the government, how it is spent, and who spends it. We begin by looking government spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (a measure of national production) for the past 80+ years.

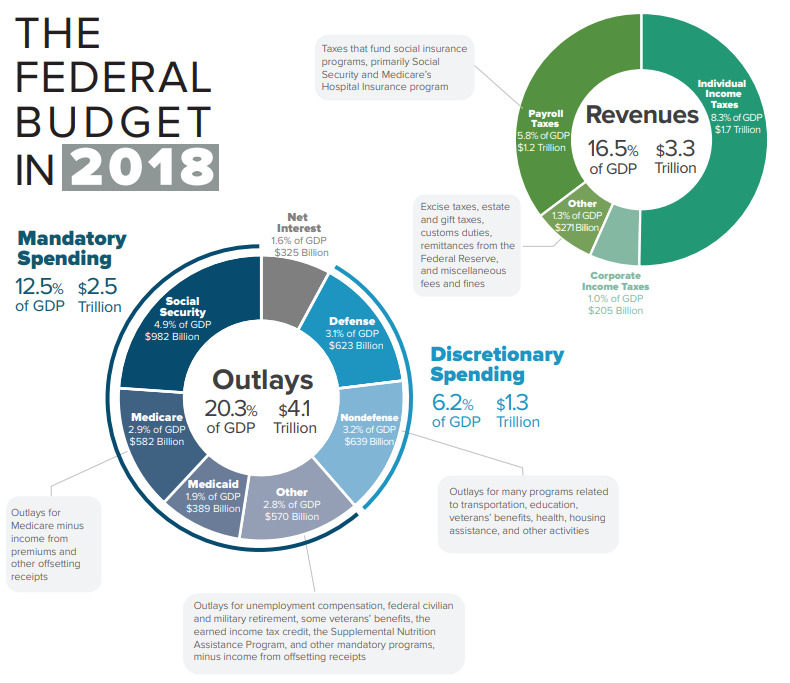

Discussions can be had on the reason why government expenditures have increased. Part of it stems from the 16th amendment which made the income tax constitutional. In addition, the role of government has changed. In the recent decades, the government has placed a larger focus on the provision of social safety nets including Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. So, what does the federal government spend its money on? And where does this money come from? The following graph shows the Congressional Budget Office’s breakdown of the federal budget.

From: Wikipedia: Mandatory spending

The United States federal budget is divided into three categories: mandatory spending, discretionary spending, and interest on debt. Also known as entitlement spending, in US fiscal policy, mandatory spending is government spending on certain programs that are mandated by law.[1] Congress established mandatory programs under authorization laws. Congress legislates spending for mandatory programs outside of the annual appropriations bill process. Congress can only reduce the funding for programs by changing the authorization law itself. This requires a 60-vote majority in the Senate to pass. Discretionary spending on the other hand will not occur unless Congress acts each year to provide the funding through an appropriations bill.

Mandatory spending has taken up a larger share of the federal budget over time.[2] In fiscal year (FY) 1965, mandatory spending accounted for 5.7 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).[3] In FY 2016, mandatory spending accounted for about 60 percent of the federal budget and over 13 percent of GDP.[4] Mandatory spending received $2.4 trillion of the total $3.9 trillion of federal spending in 2016.[4]

Entitlement programs are social welfare programs with specific requirements. Congress sets eligibility requirements and benefits for entitlement programs. If the eligibility requirements are met for a specific mandatory program, outlays are made automatically.[2] Entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare make up the bulk of mandatory spending. Together they account for nearly 50 percent of the federal budget.[2] Other mandatory spending programs include Income Security Programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and Unemployment Insurance. Federal Retirement programs for Federal and Civilian Military Retirees, Veterans programs, and various other programs that provide agricultural subsidies are also included in mandatory spending. Also included is smaller budgetary items, such as the salaries of Members of Congress and the President. The graph to the right shows a breakdown on the percent of mandatory spending each entitlement program receives.

Prior to the Great Depression, nearly all federal expenditures were discretionary. Mandatory spending grew following the passage of the Social Security Act in 1935. An increasing percentage of the federal budget became devoted to mandatory spending.[2] In 1947, Social Security accounted for just under five percent of the federal budget and less than one-half of one percent of GDP.[6] By 1962, 13 percent of the federal budget and half of all mandatory spending was committed to Social Security.[2] Less than 30 percent of all federal spending was mandatory. This percentage continued to increase when Congress amended the Social Security Act to create Medicare in 1965. Medicare is a government administered health insurance program for senior citizens.[7] In the 10 years following the creation of Medicare, mandatory spending increased from 30 percent to over 50 percent of the federal budget.

Government Revenues

From figure 12.3, we see that most of the federal government revenue is generated by income tax and payroll tax. Payroll taxes include several programs but most notably Social Security and Medicare. Only a small percentage of government revenue comes from corporate income tax and other sources, such as excise tax, tariffs, and estate taxes.

Deficits, Surplus, and Debts

From: Wikipedia: Government budget balance

A government budget is a financial statement presenting the government’s proposed revenues and spending for a financial year. The government budget balance, also alternatively referred to as general government balance,[1] public budget balance, or public fiscal balances, is the overall difference between government revenues and spending. A positive balance is called a government budget surplus, and a negative balance is a government budget deficit. A budget is prepared for each level of government (from national to local) and takes into account public social security obligations.

The meaning of “deficit” differs from that of “debt”, which is an accumulation of yearly deficits. Deficits occur when a government’s expenditures exceed the revenue that it levies. The deficit can be measured with or without including the interest payments on the debt as expenditures.[7]

The primary deficit is defined as the difference between current government spending on goods and services and total current revenue from all types of taxes net of transfer payments. The total deficit (which is often called the fiscal deficit or just the ‘deficit’) is the primary deficit plus interest payments on the debt.[7]

Economic trends can influence the growth or shrinkage of fiscal deficits in several ways. Increased levels of economic activity generally lead to higher tax revenues, while government expenditures often increase during economic downturns because of higher outlays for social insurance programs such as unemployment benefits. Changes in tax rates, tax enforcement policies, levels of social benefits, and other government policy decisions can also have major effects on public debt. For some countries, such as Norway, Russia, and members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), oil and gas receipts play a major role in public finances.

Example: Suppose that a government begins the year with $300 billion worth of debt. Further, suppose that the following year, they generate $200 billion in revenue and spend $250 billion on different government programs. In that year, the government ran a deficit of $50 billion (200-250) which increases their debt from $300 billion to $350 billion. Further, suppose that the next year, the government generated $300 billion in revenue but spend $275 billion. Because they generated more revenue than they spent, they ran a surplus. This can be used to pay down the government debt. In the example, they ran a $25 billion surplus meaning that government debt has fallen to $325 billion.

State and Local Expenditures and Revenues

The role of the state and local government is very different than that of the federal government. For example, the federal government spends more than a half-trillion dollars on national defense each year. On the other hand, state and local governments tend to spend money on the provision of services to residents. Table 12.1 below shows the 2017 state expenditures.

| Category | Spending (bil $) | Pct. of Spending |

|---|---|---|

| Education | 687.9 | 34.7 |

| Public Welfare | 675.5 | 34.0 |

| Hospitals | 88.6 | 4.5 |

| Health | 61.8 | 3.1 |

| Highways | 129.4 | 6.5 |

| Police Protection | 17.2 | 0.9 |

| Correction | 51.2 | 2.6 |

| Natural Resources | 24.0 | 1.2 |

| Parks and Recreation | 6.6 | 0.3 |

| Government Administration | 60.7 | 3.1 |

| Interest on Debt | 43.9 | 2.2 |

| Other | 137.4 | 6.9 |

In addition, the way state governments collect revenue is to a certain degree different. The table below shows how states collect tax. One component not mentioned is property tax. This will be discussed shortly as property tax is a component of local tax collection.

| Source | Revenue (bil $) | Pct. of Revenue |

|---|---|---|

| Sales Tax | 299.8 | 31.8 |

| Excise Tax | 151.2 | 16.0 |

| License Tax | 55.0 | 5.8 |

| Individual Income Tax | 350.9 | 37.2 |

| Corporate Income Tax | 44.6 | 4.7 |

| Other | 41.5 | 4.4 |

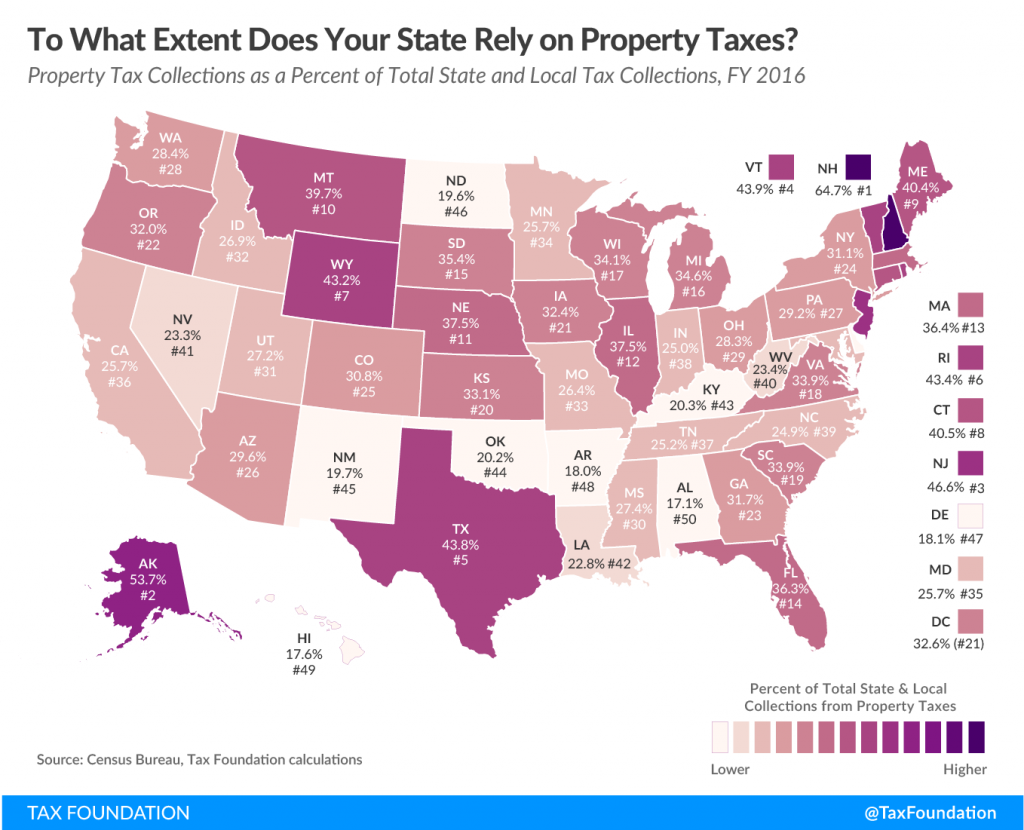

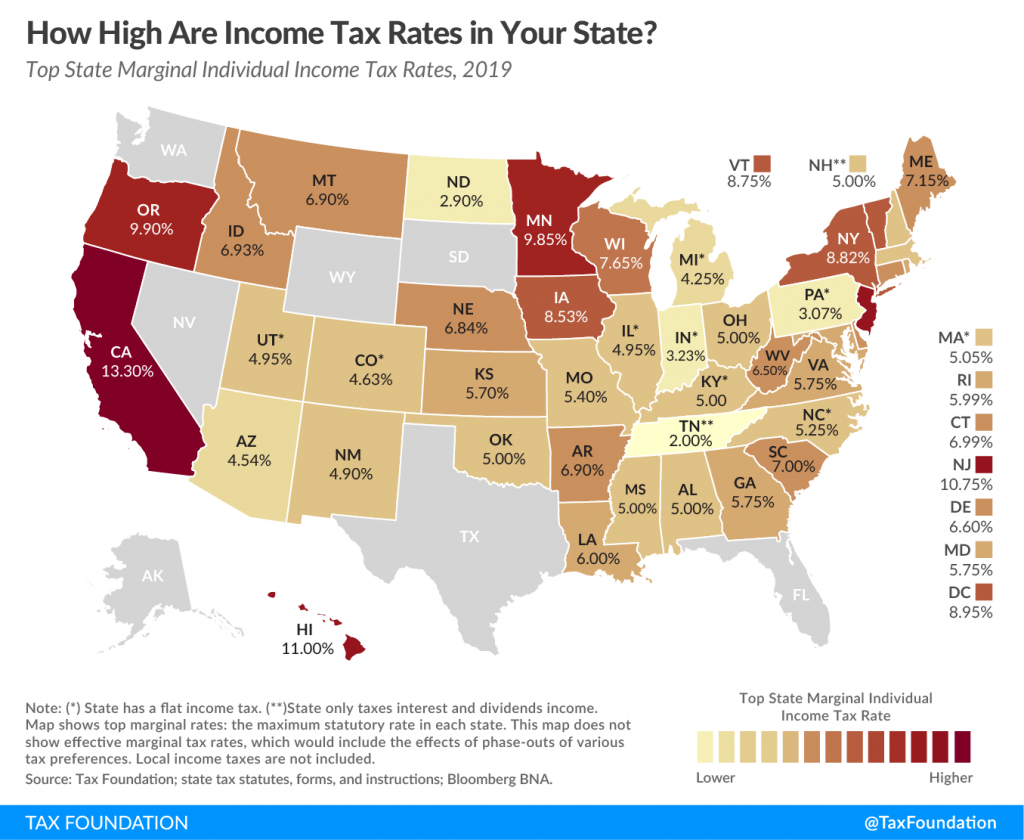

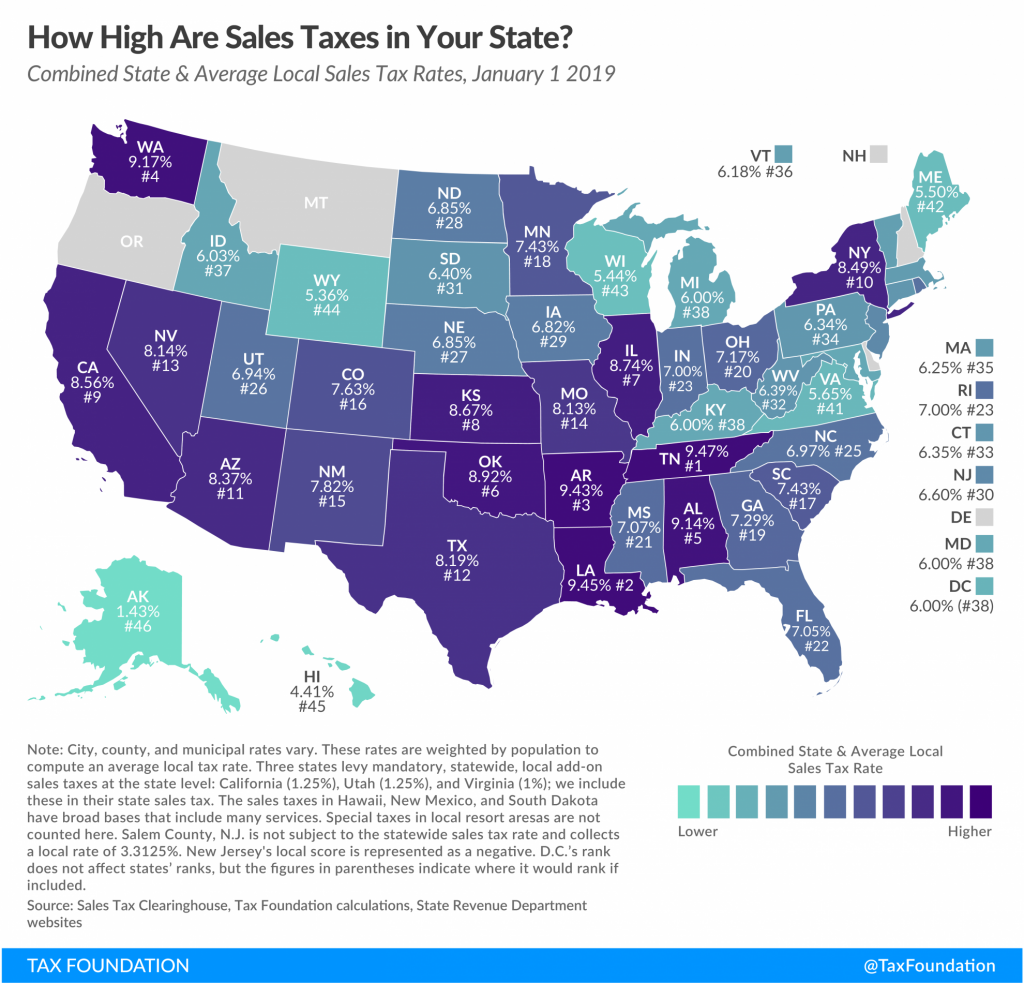

State and local governments tend to collect taxes in three different ways: income tax, property tax, and sales tax. Some states collect all three. Other states only collect fewer. For example, Alaska and New Hampshire does not collect income tax nor does it charge a sales tax. However, New Hampshire does have some of the highest property tax rates in the country. Additionally, Delaware, Montana, and Oregon do not have a sales tax while Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington do not charge an income tax. There are no states that do not have at least some property tax. The following three figures show the breakdown of each type of tax per state.

12.4 Collective action and the inefficiency of government

Similarities between Government and Markets

Regardless of what we are looking at, we always face scarcity. Individual firms, as we have discussed, face trade-offs between time, resources, effort, energy, and money. Producing more of this means less of that. This is also true for the government. Even though it may seem like the government has an infinite amount of money to spend, they do not. One dollar of expenditures on education mean one less dollar of expenditures of national defense. Therefore, both the private and public sector experience opportunity costs. Any time one action is taken, another becomes unavailable.

The Four Differences between the Private Sector and the Public Sector

Breaking the Linkage

In the private-sector, goods are allocated to those that are willing to pay for the good. The more you pay, the more you get, and vice versa. On the other hand, government programs rarely connect expenditures with payment. For example, welfare funds are distributed to those with the smallest incomes. At the same time, those with the smallest incomes also pay little to no income tax. Therefore, there is generally a greater demand for government services because people are paying less yet receiving more.

Mutual Agreement versus Majority Rule

As we discussed earlier in the book, trade is founded on the idea of mutual agreement. Both sides must agree for the trade to occur. This means that both sides must feel as though they will be better off in order to agree to the trade. On the other hand, the political process is run by majority rule. Therefore, as long as 50% +1 person agree to something, then everyone must accept the action. This is even true if it makes some groups worse off. Suppose that a new tax plan wants to significantly increase the tax rate on those in the top 1%. This will be favored by those in the bottom 99% and rejected by the top 1%. Regardless of who this helps or hurts, if the law is passed, then everyone must adhere to it.

Bundle Purchases

Think about the last time you went to a grocery store. Were there pre-selected shopping carts filled with different groceries? Were you only able to select something off of the pre-selected menu? Of course not. In the private-sector, we have the ability to purchase whatever quantities of different goods that we desire. We can mix-and-match as much as we want. On the other hand, when we vote for our political representation, we must vote for an entire package. For example, suppose that you vote for John Smith because you agree with his stance on tax policy. But, you disagree with his stance on education reform. You cannot choose one policy and reject another. When you vote for a candidate, you vote for their entire platform.

Income and Influence

In the private-sector, we vote with our dollars. The more people that like a product, the more people that buy the product, thus the more people that “vote” for the product. The more votes that a product receives, the more it will be made available. On the other hand, if no one “votes” for a product, it is unlikely it will continue to be sold. In the political sector, everyone receives one vote. Bill Gates can vote for president the same number of times as you or me. One issue that does come up is the use of money to sway others’ political leanings, but this will be discussed later in the chapter.

Political Decision-Making

In chapter 3, we discussed the supply and demand of a single good. The demand was determined by the buyer while the supply was determined by the producer. The two parties negotiate and attempt to make a trade possible. The political process is a bit different. Specifically, there are three groups to consider.

Voters demand government services. Just like a consumer, they pay for these services. Politicians supply government. Through the political process, politicians pass bills which fund programs and activities. Third, the bureaucrats provide the government services. While the politicians approve the funding, they do not administer the programs. Instead, they create agencies that make the programs possible. For example, your local congressperson authorizes the spending for air quality each and every year. But, they do not actually carryout the air quality testing. Instead, this is done by the Environmental Protection Agency. This third party adds a new dimension to the market relationship.

Voters

Voters tend to be relatively uninterested in the political process. As long as they feel as though they are getting more than they are spending and that the economy is running well, voters are happy. This is because of the rational ignorance effect.

From: Wikipedia: Rational ignorance

Rational ignorance is refraining from acquiring knowledge when the supposed cost of educating oneself on an issue exceeds the expected potential benefit that the knowledge would provide.

Ignorance about an issue is said to be “rational” when the cost of educating oneself about the issue sufficiently to make an informed decision can outweigh any potential benefit one could reasonably expect to gain from that decision, and so it would be irrational to waste time doing so. This has consequences for the quality of decisions made by large numbers of people, such as in general elections, where the probability of any one vote changing the outcome is very small.

The term is most often found in economics, particularly public choice theory, but also used in other disciplines which study rationality and choice, including philosophy (epistemology) and game theory.

The term was coined by Anthony Downs in An Economic Theory of Democracy.[1]

Politics and elections especially display the same dynamic. By increasing the number of issues that a person needs to consider to make a rational decision about candidates or policies, politicians and pundits encourage single-issue voting, party-line voting, jingoism, selling votes, or dart-throwing all of which may tip the playing field in favor of politicians who do not actually represent the electorate.

This does not mean that voters make poor and biased decisions: rather that in carrying out their everyday responsibilities (like working and taking care of a family), many people do not have the time to devote to researching every aspect of a candidate’s policies. So many people find themselves making rational decisions meaning they let others who are more versed in the subject do the research and they form their opinion based on the evidence provided. They are being rationally ignorant not because they don’t care but because they simply do not have the time.

Because the cost/benefit ratio increases with increasing costs or decreasing the benefit, the same effect can occur when politicians protect their policy decisions from the preferences of the public. To the degree that the electorate perceives their individual votes to count for less, they will have less incentive to spend any time actually learning any details about the candidate(s).

A more nuanced example occurs when a voter identifies with a particular political party, akin to the adoption of a favorite movie critic. Based on prior experience a responsible voter will seek politicians or a political party that draws conclusions about social policy that are similar to what their own conclusions would have been had they done a complete analysis. But when voters find themselves agreeing with the same party or politician across a number of election cycles, many voters simply trust that the same will continue to be true and “vote the ticket,” also referred to as straight-ticket voting, instead of wasting time on a complete investigation.

Politicians

This is quite simple. Politicians want to be re-elected. Therefore, they tend to favor policies that increase their likelihood of being re-elected, even if the policy may not be the best choice for the country.

Bureaucrats

In the United States, the bureaucrats are those that run and manage the different governing agencies in the executive branch. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Securities and Exchange Commission. These agencies are charged by the government to perform certain tasks with a given budget.

The outcome is generally the same: the bureaucrat aims to maximize their budget. Agencies do not want to get smaller. A larger budget generally means more regulatory power, more authority, more staffing, and a greater sense of power.

12.5 When government works well

The Four Types of Spending

We can think about the ways that money is spent and the ways that money is collected. Specifically, we can think about how these things are concentrated within the voters. For example, is the money for a project collected from the entire tax base or is it collected from a relatively small, concentrated group. Money collected from income taxes can be thought of as coming from the entire tax base since most people pay at least some federal income tax. On the other hand, money collected from the sale of cigarettes comes from a concentrated group. We can similarly think about how the benefits of a government program are earned. For example, Social Security benefits everybody (eventually). On the other hand, a federal project that allows for a new farmers market to be built in Erie is one with concentrated benefits. We can think about the four different combinations using the table below.

| – | – | Distribution of Benefits | Distribution of Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| – | – | Widespread | Concentrated |

| Distribution of Costs | Widespread | (Widespread, Widespread) | (Widespread, Concentrated) |

| Distribution of Costs | Concentrated | (Concentrated, Widespread) | (Concentrated, Concentrated) |

Widespread Costs and Widespread Benefits

These types of projects deal with the free-rider problem. As discussed in the previous chapter, certain goods will be under-provided if there is not enough payment. Under-payment occurs because people believe that the good will be provided regardless as their own contribution is small relative to the entire group. But when too many people have the same thought, funding is severely cut, and provision is either reduced or eliminated. As discussed, one way for this to be resolved is by government provision of the good. At the same time, the government can collect taxes, which are coercive, to provide enough of the good. These types of programs are generally efficient as they allow for the provision of these goods that would not be possible in the private-sector.

Some examples of this type of cost/benefit relationship are national defense, the interstate system, and, for the most part, public education.

Concentrated Costs and Concentrated Benefits

Consider a new sub-development being built. This new development will contain over 300 houses. This will require an extension of the water and sewer system, new electric and natural gas lines, and perhaps even an addition on the local elementary school. One way this could be accomplished is through increasing the tax rate on the entire city (however taxes are collected). But this does not seem equitable since the people that will benefit are those that are living in the new development. Therefore, the city could also charge a “user charge” which is a payment that the users of a specific good or service are required to pay if they wish to use that good or service. In this example, the fees could be paid by the developer who would then pass those fees on to the new homeowners. These arrangements are also efficient as they match the cost of the provision of government services to those who use those government services.

These types of arrangements adhere to the benefits principle,

From: Wikipedia: Benefit principle

The benefit principle is a concept in the theory of taxation from public finance. It bases taxes to pay for public-goods expenditures on a politically-revealed willingness to pay for benefits received. The principle is sometimes likened to the function of prices in allocating private goods.[1] In its use for assessing the efficiency of taxes and appraising fiscal policy, the benefit approach was initially developed by Knut Wicksell (1896) and Erik Lindahl (1919), two economists of the Stockholm School.[2] Wicksell’s near-unanimity formulation of the principle was premised on a just income distribution. The approach was extended in the work of Paul Samuelson, Richard Musgrave,[3] and others.[4] It has also been applied to such subjects as tax progressivity, corporation taxes, and taxes on property or wealth.[5] The unanimity-rule aspect of Wicksell’s approach in linking taxes and expenditures is cited as a point of departure for the study of constitutional economics in the work of James Buchanan.[6][3]

For example, consider an education project that is being voted on by five counties in northwestern Pennsylvania. The project is expected to cost $50 million but it also expected to create $150 million worth of benefits. Because the benefits exceed the costs, it is an economically efficient program that should be undertaken. However, those benefits will not be uniformly distributed. They must decide on a way to pay for this program. Two different possibilities are given. A summary is given below.

| County | Benefits | Tax Payment Plan A | Tax Payment Plan B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erie | $90 | $10 | $30 |

| Crawford | $45 | $10 | $15 |

| Warren | $6 | $10 | $2 |

| Mercer | $6 | $10 | $2 |

| Venango | $3 | $10 | $1 |

| Total | $150 | $50 | $50 |

If the county executives need a majority for it to be approved, they will always get to an efficient action if the payments are distributed according to the distribution of the benefits. According to the first payment plan, where the $50 million cost is split equally, the vote will fail 2-3. This is because three of the counties will pay more than the benefits they receive. On the other hand, the second tax payment plan, because the benefits for each individual county exceed the costs, will pass 5-0. For example, Erie County receives 90/150 or 60% of the benefits and will pay 60% of the $50 million cost, or $30 million.

On the other hand, suppose they are also voting on a new prison. The prison is expected to cost $120 million and yield $100 million in benefits. Because the costs exceed the benefits, the prison should not be built. But, again, consider the two voting arrangements.

| County | Benefits | Tax Payment Plan A | Tax Payment Plan B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erie | $35 | $24 | $42 |

| Crawford | $30 | $24 | $36 |

| Warren | $25 | $24 | $30 |

| Mercer | $5 | $24 | $6 |

| Venango | $5 | $24 | $6 |

| Total | $100 | $120 | $120 |

In this scenario, the plan is approved under the first plan by a vote of 3-2 since Erie, Crawford, and Warren Counties all receive more benefits than costs. What this shows is that voting coalitions can be formed which permit costs to be split onto groups that receive very little to no benefit. But, when the costs are split according to the benefits, the bill will fail 0-5.

Ultimately, when costs are distributed the same as the benefits, the vote will always be unanimous. If the benefits exceed the cost, the vote will be 5-0 whereas if the costs exceed the benefits, the vote will fail 0-5.

12.6 When governments work poorly

Widespread Costs, Concentrated Benefits

In this scenario, everybody pays for a geographically concentrated program. One type of spending created is called pork-barrel spending.

From: Wikipedia: Pork barrel

Pork barrel is a metaphor for the appropriation of government spending for localized projects secured solely or primarily to bring money to a representative’s district. The usage originated in American English.[1] Scholars use it as a technical term regarding legislative control of local appropriations.[2][3] In election campaigns, the term is used in derogatory fashion to attack opponents.

Typically, “pork” involves funding for government programs whose economic or service benefits are concentrated in a particular area but whose costs are spread among all taxpayers. Public works projects, certain national defense spending projects, and agricultural subsidies are the most commonly cited examples.

An early example of pork barrel politics in the United States was the Bonus Bill of 1817, which was introduced by Democrat John C. Calhoun to construct highways linking the Eastern and Southern United States to its Western frontier using the earnings bonus from the Second Bank of the United States. Calhoun argued for it using general welfare and post roads clauses of the United States Constitution. Although he approved of the economic development goal, President James Madison vetoed the bill as unconstitutional.

One of the most famous alleged pork-barrel projects was the Big Dig in Boston, Massachusetts. The Big Dig was a project to relocate an existing 3.5-mile (5.6 km) section of the Interstate Highway System underground. The official planning phase started in 1982; the construction work was done between 1991 and 2006; and the project concluded on December 31, 2007. It ended up costing US$14.6 billion, or over US$4 billion per mile.[10] Tip O’Neill (D-Mass), after whom one of the Big Dig tunnels was named, pushed to have the Big Dig funded by the federal government while he was the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.[11]

During the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, the Gravina Island Bridge (also known as the “Bridge to Nowhere”) in Alaska was cited as an example of pork barrel spending. The bridge, pushed for by Republican Senator Ted Stevens, was projected to cost $398 million and would connect the island’s 50 residents and the Ketchikan International Airport to Revillagigedo Island and Ketchikan.[12] Former Hawaii Senator Daniel Inouye described himself as “the No. 1 earmarks guy in the U.S. Congress.”[13] Inouye regularly passed earmarks for funding in the state of Hawaii including military and transportation spending.[14]

Pork-barrel projects, which differ from earmarks, are added to the federal budget by members of the appropriation committees of United States Congress. This allows delivery of federal funds to the local district or state of the appropriation committee member, often accommodating major campaign contributors. To a certain extent, a member of Congress is judged by their ability to deliver funds to their constituents. The Chairman and the ranking member of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations are in a position to deliver significant benefits to their states. Researchers Anthony Fowler and Andrew B. Hall claim that this still does not account for the high reelection rates of incumbent representatives in American legislatures.[15]

The Madrid–Seville high-speed line was a noted example of pork barrel politics in Spain. Pasqual Maragall revealed details of an unwritten agreement between him and Felipe González, the prime minister at the time who was from Seville. The agreement was that Barcelona would receive the 1992 Summer Olympics and Seville would receive the high-speed railway line (which opened in 1992).[16] This was in spite of position of the Madrid–Barcelona high-speed rail line as Spain’s most profitable high-speed line.[17] Barcelona received its AVE connection in 2008, though with many advantages that the line to Seville does not have, e.g. full-speed bypasses LAV Madrid – Sevilla and LAV Madrid – Zaragoza – Barcelona: the decision to construct the line to Seville was only taken in 1986 and construction was rushed, so that the line would be ready for the Seville Expo ’92.

Concentrated Costs, Widespread Benefits

This type of spending is used by politicians to pay for projects while marginalizing as few voters as possible. For example, say a politician wants to fund a new healthcare program. This will obviously be very expensive and require new taxes. Voters do not like taxes. Instead, the politician could place a tax on the wealthiest Americans. This would create a program funded by a small group of people (no longer voting for the politician), but would benefit a large group of people (who now happily vote for the politician.)

Causes of Government Inefficiency

Special-Interest Effect

Why do government policies tend to favor small groups? This is because the small groups that are most affected have the most to gain or lose. For example, sugar prices in the United States are some of the highest in the world. This is because the group of sugar cane growers in the United States has lobbied for a strict import quota which limits how much sugar can be imported from other countries. For instance, in 2017, the average price of a pound of sugar in the United States was 63 cents per pound compared to a global average price of 20 cents per pound. For the average American, this may account for just $10-$20 per year, but for the sugar cane growers, this can mean billions of dollars. The average American has very little incentive to to push against these quotas since it would save them very little whereas the sugar cane growers can, and will, spend a significant amount of money and resources to keep the quotas in place due to the millions, or billions, of dollars available to gain.

Logrolling

From: Wikipedia: Logrolling

Logrolling is the trading of favors, or quid pro quo, such as vote trading by legislative members to obtain passage of actions of interest to each legislative member.[1] In organizational analysis, it refers to a practice in which different organizations promote each other’s agendas, each in the expectation that the other will reciprocate. In an academic context, the Nuttall Encyclopedia describes logrolling as “mutual praise by authors of each other’s work”.

There are three types of logrolling:

- Logrolling in direct democracies: a few individuals vote openly, and votes are easy to trade, rearrange, and observe. Direct democracy is pervasive in representative assemblies and small-government units

- Implicit logrolling: large bodies of voters decide complex issues and trade votes without a formal vote trade (Buchanan and Tullock 1962[2])

- Distributive logrolling: enables policymakers to achieve their public goals. These policymakers logroll to ensure that their district policies and pork barrel packages are put into practice regardless of whether their policies are actually efficient (Evans 1994[3] and Buchanan and Tullock 1962[2]).

Distributive logrolling is the most prevalent kind of logrolling found in a democratic system of governance.[4]

“Quid pro quo” sums up the concept of logrolling in the United States’ political process today. Logrolling is the process by which politicians trade support for one issue or piece of legislation in exchange for another politician’s support, especially by means of legislative votes (Holcombe 2006[5]). If a legislator logrolls, he initiates the trade of votes for one particular act or bill in order to secure votes on behalf of another act or bill. Logrolling means that two parties will pledge their mutual support, so both bills can attain a simple majority. For example, a vote on behalf of a tariff may be traded by a congressman for a vote from another congressman on behalf of an agricultural subsidy to ensure that both acts will gain a majority and pass through the legislature (Shughart 2008[6]). Logrolling cannot occur during presidential elections, where a vast voting population necessitates that individual votes have little political power, or during secret-ballot votes (Buchanan and Tullock 1962[2]). Because logrolling is pervasive in the political process, it is important to understand which external situations determine when, why, and how logrolling will occur, and whether it is beneficial, efficient, or neither.

An Example

Table 12.6 explains another example of logrolling. In the example, we have three individuals: Tanya, Alvin, and Rebecca. Tanya favors subsidies for agriculture, Alvin favors school construction, and Rebecca favors the recruitment of more firefighters. It seems as if the proposals are doomed to fail because each is opposed by a majority of voters. Even so, this may not be the outcome. Tanya may visit Rebecca and tell her that she will vote for Rebecca’s bill to recruit more firefighters so long as Rebecca votes for her policy, subsidies for agriculture, in return. Now both proposals will win because they have gained a simple majority, even though in reality the subsidy is opposed by two of the three voters. It’s easy to see the Coase theorem at work in examples like this. Here, transaction costs are low, so mutually beneficial agreements are found, and the person who values the service the most will hold it (Browning and Browning 1979[15]). Still, outcomes may be inefficient.

| Person | Agriculture | Tax | Vote | School | Tax | Vote | Fire | Tax | Vote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanya | $300 | $200 | Y | $150 | $200 | N | $100 | $200 | N |

| Alvin | $150 | $200 | N | $350 | $200 | Y | $150 | $200 | N |

| Rebecca | $100 | $200 | N | $50 | $200 | N | $225 | $200 | Y |

| Total | $550 | $600 | Inefficient | $550 | $600 | Inefficient | $475 | $600 | Inefficient |

If the sum of the total benefit of the legislation for all the voters is less than the cost of the legislation itself, the legislation is inefficient. Despite its inefficiency, however, it still may pass if logrolling is permitted. If Tanya trades her vote to recruit more firemen to Rebecca in exchange for Rebecca’s vote in favor of agriculture subsidies, a mutually beneficial agreement will be reached, even though the outcome is inefficient. On the other hand, if the sum of the total benefit of the legislation for all voters is greater than the cost of the legislation itself, the legislation is efficient. If Tanya trades her vote once again for Rebecca’s vote, both parties will reach a mutually beneficial agreement and an efficient outcome.

If the sum of the total benefit of the legislation for all the voters is less than the cost of the legislation itself, the legislation is inefficient. Despite its inefficiency, however, it still may pass if logrolling is permitted. If Tanya trades her vote to recruit more firemen to Rebecca in exchange for Rebecca’s vote in favor of agriculture subsidies, a mutually beneficial agreement will be reached, even though the outcome is inefficient. On the other hand, if the sum of the total benefit of the legislation for all voters is greater than the cost of the legislation itself, the legislation is efficient. If Tanya trades her vote once again for Rebecca’s vote, both parties will reach a mutually beneficial agreement and an efficient outcome.

Shortsightedness Effect

As mentioned earlier, politicians aim to be re-elected. In order to accomplish this, they may need to approve spending that may not be good for the long-run, but is good for the short-run. For instance, a new jobs program may require extensive debt-financing. But this program may create jobs today. Therefore, the politician should favor this plan even if the long-term costs are large. It does not matter if you cannot be re-elected in twenty years if you lose the next election.

Generally, politicians favor policies with immediate and clear benefits in the near-term but whose costs are difficult-to-identify and occur over time.

Rent-Seeking

From: Wikipedia: Rent-seeking

Rent-seeking is a concept in public choice theory, as well as in economics, that involves seeking to increase one’s share of existing wealth without creating new wealth. Rent-seeking results in reduced economic efficiency through misallocation of resources, reduced wealth-creation, lost government revenue, heightened income inequality,[1] and potential national decline.

Attempts at capture of regulatory agencies to gain a coercive monopoly can result in advantages for the rent seeker in a market while imposing disadvantages on their incorrupt competitors. This is one of many possible forms of rent-seeking behavior.

Rent-seeking is an attempt to obtain economic rent (i.e., the portion of income paid to a factor of production in excess of what is needed to keep it employed in its current use) by manipulating the social or political environment in which economic activities occur, rather than by creating new wealth. Rent-seeking implies extraction of uncompensated value from others without making any contribution to productivity. The classic example of rent-seeking, according to Robert Shiller, is that of a feudal lord who installs a chain across a river that flows through his land and then hires a collector to charge passing boats a fee to lower the chain. There is nothing productive about the chain or the collector. The lord has made no improvements to the river and is not adding value in any way, directly or indirectly, except for himself. All he is doing is finding a way to make money from something that used to be free.[5]

In many market-driven economies, much of the competition for rents is legal, regardless of harm it may do to an economy. However, some rent-seeking competition is illegal—such as bribery or corruption.

Rent-seeking is distinguished in theory from profit-seeking, in which entities seek to extract value by engaging in mutually beneficial transactions.[6] Profit-seeking in this sense is the creation of wealth, while rent-seeking is “profiteering” by using social institutions, such as the power of the state, to redistribute wealth among different groups without creating new wealth.[7] In a practical context, income obtained through rent-seeking may contribute to profits in the standard, accounting sense of the word.

An example of rent-seeking in a modern economy is spending money on lobbying for government subsidies in order to be given wealth that has already been created, or to impose regulations on competitors, in order to increase market share.[12] Another example of rent-seeking is the limiting of access to lucrative occupations, as by medieval guilds or modern state certifications and licensures. Taxi licensing is a textbook example of rent-seeking.[13] To the extent that the issuing of licenses constrains overall supply of taxi services (rather than ensuring competence or quality), forbidding competition from other vehicles for hire renders the (otherwise consensual) transaction of taxi service a forced transfer of part of the fee, from customers to taxi business proprietors.

The concept of rent-seeking would also apply to corruption of bureaucrats who solicit and extract “bribe” or “rent” for applying their legal but discretionary authority for awarding legitimate or illegitimate benefits to clients.[14] For example, tax officials may take bribes for lessening the tax burden of the taxpayers.

Regulatory Capture Theory

From: Wikipedia: Regulatory capture

Regulatory capture (also client politics) is a corruption of authority that occurs when a political entity, policymaker, or regulatory agency is co-opted to serve the commercial, ideological, or political interests of a minor constituency, such as a particular geographic area, industry, profession, or ideological group[1].[2] When regulatory capture occurs, a special interest is prioritized over the general interests of the public, leading to a net loss for society. Government agencies suffering regulatory capture are called “captured agencies.” The theory of client politics is related to that of rent-seeking and political failure; client politics “occurs when most or all of the benefits of a program go to some single, reasonably small interest (e.g., industry, profession, or locality) but most or all of the costs will be borne by a large number of people (for example, all taxpayers).”[3]

For public choice theorists, regulatory capture occurs because groups or individuals with a high-stakes interest in the outcome of policy or regulatory decisions can be expected to focus their resources and energies in attempting to gain the policy outcomes they prefer, while members of the public, each with only a tiny individual stake in the outcome, will ignore it altogether.[4] Regulatory capture refers to the actions by interest groups when this imbalance of focused resources devoted to a particular policy outcome is successful at “capturing” influence with the staff or commission members of the regulatory agency, so that the preferred policy outcomes of the special interest groups are implemented.

The idea of regulatory capture has an economic basis: vested interests in an industry have the greatest financial stake in regulatory activity of any social agent and are thus more likely to be moved to influence the regulatory body than relatively dispersed individual consumers,[4] each of whom has little particular incentive to try to influence regulators. When regulators form expert bodies to examine policy, these invariably feature current or former industry members, or at the very least, individuals with lives and contacts in the industry to be reviewed. Capture is also facilitated in situations where consumers or taxpayers have a poor understanding of underlying issues and businesses enjoy a knowledge advantage.[13]

Crony Capitalism

From: Wikipedia: Crony capitalism

Crony capitalism is an economic system in which businesses thrive not as a result of risk, but rather as a return on money amassed through a nexus between a business class and the political class. This is often achieved by using state power rather than competition in managing permits, government grants, tax breaks, or other forms of state intervention[1][2] over resources where the state exercises monopolist control over public goods, for example, mining concessions for primary commodities or contracts for public works. Money is then made not merely by making a profit in the market, but through profiteering by rent seeking using this monopoly or oligopoly. Entrepreneurship and innovative practices which seek to reward risk are stifled since the value-added is little by crony businesses, as hardly anything of significant value is created by them, with transactions taking the form of trading. Crony capitalism spills over into the government, the politics, and the media,[3] when this nexus distorts the economy and affects society to an extent it corrupts public-serving economic, political, and social ideals.

Crony capitalism exists along a continuum. In its lightest form, crony capitalism consists of collusion among market players which is officially tolerated or encouraged by the government. While perhaps lightly competing against each other, they will present a unified front (sometimes called a trade association or industry trade group) to the government in requesting subsidies or aid or regulation.[7] For instance, newcomers to a market then need to surmount significant barriers to entry in seeking loans, acquiring shelf space, or receiving official sanction. Some such systems are very formalized, such as sports leagues and the Medallion System of the taxicabs of New York City, but often the process is more subtle, such as expanding training and certification exams to make it more expensive for new entrants to enter a market and thereby limiting potential competition. In technological fields, there may evolve a system whereby new entrants may be accused of infringing on patents that the established competitors never assert against each other. The term crony capitalism is generally used when these practices either come to dominate the economy as a whole, or come to dominate the most valuable industries in an economy.[2] Intentionally ambiguous laws and regulations are common in such systems. Taken strictly, such laws would greatly impede practically all business activity, but in practice they are only erratically enforced. The specter of having such laws suddenly brought down upon a business provides an incentive to stay in the good graces of political officials. Troublesome rivals who have overstepped their bounds can have these laws suddenly enforced against them, leading to fines or even jail time. Even in high-income democracies with well-established legal systems and freedom of the press in place, a larger state is generally associated with increased political corruption.[8]

The term crony capitalism was initially applied to states involved in the 1997 Asian financial crisis such as Thailand and Indonesia. Southeast Asian nations still score very poorly in rankings measuring this. Hong Kong[9] and Malaysia[10] are perhaps most noted for this, and the term has also been applied to the system of oligarchs in Russia.[11][12] Other states to which the term has been applied include India,[13] in particular the system after the 1990s liberalization, whereby land and other resources were given at throwaway prices in the name of public private partnerships, the more recent coal-gate scam and cheap allocation of land and resources to Adani SEZ under the Congress and BJP governments.[14]

Similar references to crony capitalism have been made to other countries such as Argentina[15] and Greece.[16] Wu Jinglian, one of China’s leading economists[17] and a longtime advocate of its transition to free markets, says that it faces two starkly contrasting futures, namely a market economy under the rule of law or crony capitalism.[18] A dozen years later, prominent political scientist Pei Minxin had concluded that the latter course had become deeply embedded in China.[19]

Many prosperous nations have also had varying amounts of cronyism throughout their history, including the United Kingdom especially in the 1600s and 1700s, the United States[2][20] and Japan.

More direct government involvement in a specific sector can also lead to specific areas of crony capitalism, even if the economy as a whole may be competitive. This is most common in natural resource sectors through the granting of mining or drilling concessions, but it is also possible through a process known as regulatory capture where the government agencies in charge of regulating an industry come to be controlled by that industry. Governments will often establish in good faith government agencies to regulate an industry. However, the members of an industry have a very strong interest in the actions of that regulatory body while the rest of the citizenry are only lightly affected. As a result, it is not uncommon for current industry players to gain control of the watchdog and to use it against competitors. This typically takes the form of making it very expensive for a new entrant to enter the market. An 1824 landmark United States Supreme Court ruling overturned a New York State-granted monopoly (“a veritable model of state munificence” facilitated by Robert R. Livingston, one of the Founding Fathers) for the then-revolutionary technology of steamboats.[23] Leveraging the Supreme Court’s establishment of Congressional supremacy over commerce, the Interstate Commerce Commission was established in 1887 with the intent of regulating railroad robber barons. President Grover Cleveland appointed Thomas M. Cooley, a railroad ally, as its first chairman and a permit system was used to deny access to new entrants and legalize price fixing.[24]

The defense industry in the United States is often described as an example of crony capitalism in an industry. Connections with the Pentagon and lobbyists in Washington are described by critics as more important than actual competition due to the political and secretive nature of defense contracts. In the Airbus-Boeing WTO dispute, Airbus (which receives outright subsidies from European governments) has stated Boeing receives similar subsidies which are hidden as inefficient defense contracts.[25] Other American defense companies were put under scrutiny for no-bid contracts for Iraq War and Hurricane Katrina related contracts purportedly due to having cronies in the Bush administration.[26]

Gerald P. O’Driscoll, former vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, stated that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac became examples of crony capitalism as government backing let Fannie and Freddie dominate mortgage underwriting, saying. “The politicians created the mortgage giants, which then returned some of the profits to the pols—sometimes directly, as campaign funds; sometimes as “contributions” to favored constituents”.[27]

Bootleggers and Baptists

From: Wikipedia: Bootleggers and Baptists

Bootleggers and Baptists is a concept put forth by regulatory economist Bruce Yandle,[1] derived from the observation that regulations are supported both by groups that want the ostensible purpose of the regulation, and by groups that profit from undermining that purpose.[2]

For much of the 20th century, Baptists and other evangelical Christians were prominent in political activism for Sunday closing laws restricting the sale of alcohol. Bootleggers sold alcohol illegally, and got more business if legal sales were restricted.[1] Yandle wrote that “Such a coalition makes it easier for politicians to favor both groups. … the Baptists lower the costs of favor-seeking for the bootleggers, because politicians can pose as being motivated purely by the public interest even while they promote the interests of well-funded businesses. … [Baptists] take the moral high ground, while the bootleggers persuade the politicians quietly, behind closed doors.”[3]

The mainstream economic theory of regulation treats politicians and administrators as brokers among interest groups.[4][5] Bootleggers and Baptists is a specific idea in the subfield of regulatory economics that attempts to predict which interest groups will succeed in obtaining rules they favor. It holds that coalitions of opposing interests that can agree on a common rule will be more successful than one-sided groups.[6]

Baptists do not merely agitate for legislation, they help monitor and enforce it (a law against Sunday alcohol sales without significant public support would likely be ignored, or be evaded through bribery of enforcement officers). Thus bootleggers and Baptists is not just an academic restatement of the common political accusation that shadowy for-profit interests are hiding behind public-interest groups to fund deceptive legislation. It is a rational theory[7] to explain relative success among types of coalitions.[1][8][9]

Another part of the theory is that bootleggers and Baptists produce suboptimal legislation.[10] Although both groups are satisfied with the outcome, broader society would be better off either with no legislation or different legislation.[11] For example, a surtax on Sunday alcohol sales could reduce Sunday alcohol consumption as much as making it illegal. Instead of enriching bootleggers and imposing policing costs, the surtax could raise money to be spent on, say, property tax exemptions for churches and alcoholism treatment programs. Moreover, such a program could be balanced to reflect the religious beliefs and drinking habits of everyone, not just certain groups. From the religious point of the view, the bootleggers have not been cut out of the deal, the government has become the bootlegger.[3]

Although the bootleggers and Baptists story has become a standard idea in regulatory economics,[12] it has not been systematically validated as an empirical proposition. It is a catch-phrase useful in analyzing regulatory coalitions rather than an accepted principle of economics.[13]

In 2015, liquor stores in the “wet counties” of Arkansas allied with local religious leaders to oppose statewide legalization of alcohol sales. Where the religious groups were opposed on moral grounds, the liquor stores were concerned over the potential loss of customers if rival stores were permitted to open in the “dry” counties of the state.[14]

Bootleggers and Baptists has been invoked to explain nearly every political alliance for regulation in the United States in the last 30 years including the Clean Air Act,[15] interstate trucking,[16] state liquor stores,[17] the Pure Food and Drug Act,[18] environmental policy,[19] regulation of genetically modified organisms,[20] the North American Free Trade Agreement,[21] environmental politics,[22] gambling legislation,[23] blood donation,[24] wine regulation,[25] and the tobacco settlement.[26]