Eukaryotes

Chapter 6 Introduction

Humans have been familiar with macroscopic organisms (organisms big enough to see with the unaided eye) since before there was a written history, and it is likely that most cultures distinguished between animals and land plants, and most probably included the macroscopic fungi as plants. Therefore, it became an interesting challenge to deal with the world of microorganisms once microscopes were developed a few centuries ago. Many different naming schemes were used over the last couple of centuries, but it has become the most common practice to refer to eukaryotes that are not land plants, animals, or fungi as protists.

This name was first suggested by Ernst Haeckel in the late nineteenth century. It has been applied in many contexts and has been formally used to represent a kingdom-level taxon called Protista. However, many modern systematists (biologists who study the relationships among organisms) are beginning to shy away from the idea of formal ranks such as kingdom and phylum. Instead, they are naming taxa as groups of organisms thought to include all the descendants of a last common ancestor (monophyletic group). During the past two decades, the field of molecular genetics has demonstrated that some protists are more related to animals, plants, or fungi than they are to other protists. Therefore, not including animals, plants, and fungi make the kingdom Protista a paraphyletic group, or one that does not include all descendents of its common ancestor. For this reason, protist lineages originally classified into the kingdom Protista continue to be examined and debated. In the meantime, the term “protist” still is used informally to describe this tremendously diverse group of eukaryotes.

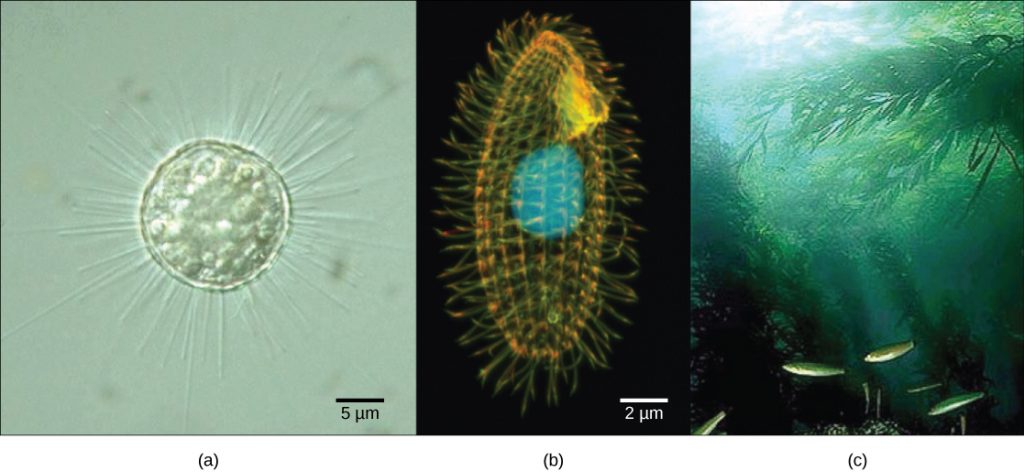

Most protists are microscopic, unicellular organisms that are abundant in soil, freshwater, brackish, and marine environments. They are also common in the digestive tracts of animals and in the vascular tissues of plants. Others invade the cells of other protists, animals, and plants. Not all protists are microscopic. Some have huge, macroscopic cells, such as the plasmodia (giant amoebae) of myxomycete slime molds or the marine green alga Caulerpa, which can have single cells that can be several meters in size. Some protists are multicellular, such as the red, green, and brown seaweeds. It is among the protists that one finds the wealth of ways that organisms can grow.