1 Welcome to Economics

1.1 Introduction

The Complexity of the Economy

The economy is complex.

A simple sentence to start the semester, but something that is important to remember as we move through this semester. Even if you take both introductory microeconomics and macroeconomics, you will only scratch the surface of how complex the economy is. Consider this scenario below.

Pretend that you intend to construct a regular yellow pencil. What do you need? You will need some wood (cedar wood to be specific), graphite (which comprises the “lead” in the pencil), rubber for the eraser, and metal for the ferrule (the band on the top that connects the eraser to the rest of the pencil.) But, where will you find the wood? Will you need to cut down a tree? If so, where will you find the resources needed to do that like a saw, goggles, gasoline for the saw, etc. Already you are seeing the sheer number of connections before we even have a felled tree. To create something as simple as a pencil, we require the assistance of thousands, or more likely tens of thousands, of others. Now, consider an iPhone or a Galaxy tablet and the sheer increase in complexity with these goods.

The scenario above is not something I came up with. Instead, it is a scenario that countless students have been exposed to over the past half-century. In 1958, Leonard Read published I, Pencil which is the story of the life of a pencil. If you would like to read the short story, you can visit the Foundation for Economic Education or you can also watch a short movie adapted from the book by the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

The Central Problem of Economics

Many students come into economics not really knowing what they will learn. Some students think issues like taxes and the stock market will be discussed. Others believe this is a course about money. None of those things are true. Instead, economics is the study of decision-making due to scarcity of resources.

As humans, our wants are unlimited. While we all have basic needs like food, water, and shelter, it is our desire for wants that puts a strain on the economy. Therefore, we need to decide how to best use our scarce resources. This is the crux of the study of economics.

Over the next several sections we will discuss the ways that individuals make decisions and the way those decisions impacts groups of people. These pillars of economic thought will guide us through the rest of the semester.

1.2 Economic principles of choice

In this section, we will discuss the ways that individuals make decisions. This will be our first set of the pillars of economic thought.

Trade-offs and their Costs

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade-off

A trade-off (or trade-off) is a situational decision that involves diminishing or losing one quality, quantity or property of a set or design in return for gains in other aspects. In simple terms, a trade-off is where one thing increases and another must decrease. Trade-offs stem from limitations of many origins, including simple physics – for instance, only a certain volume of objects can fit into a given space, so a full container must remove some items in order to accept any more, and vessels can carry a few large items or multiple small items. Trade-offs also commonly refer to different configurations of a single item, such as the tuning of strings on a guitar to enable different notes to be played, as well as allocation of time and attention towards different tasks.

The concept of a trade-off suggests a tactical or strategic choice made with full comprehension of the advantages and disadvantages of each setup. An economic example is the decision to invest in stocks, which are risky but carry great potential return, versus bonds, which are generally safer but with lower potential returns.

Every decision we make comes with lost opportunity. If you choose to attend Penn State, that means that you cannot attend West Virginia University. If you choose to have a hamburger for lunch, you are also choosing to not have pizza or chicken tenders for lunch (unless you are really hungry, of course!) If you spend $1 on one item, you are also losing the ability to spend that dollar on another item.

The same thing goes for businesses and the government. If a company has a scare number of resources, they have to decide how to best use them. Suppose that a restaurant has a surplus of $2,000 to spend to introduce new items. They can either buy a new ice cream machine or a new salad bar. If they choose to buy the ice cream machine, that means they have also decided not to get a salad bar.

Similarly, when the government decides to spend an additional $100 million on highways, it also means that said money is no longer available for education, veteran’s affairs, or environmental protection.

Opportunity Cost

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade-off and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opportunity_cost

In economics, a trade-off is expressed in terms of the opportunity cost of a particular choice, which is the loss of the most preferred alternative given up. A trade-off, then, involves a sacrifice that must be made to obtain a certain product, service or experience, rather than others that could be made or obtained using the same required resources. For example, for a person going to a basketball game, their opportunity cost is the loss of the alternative of watching a particular television program at home. If the basketball game occurs during her or his working hours, then the opportunity cost would be several hours of lost work, as she/he would need to take time off work.

The New Oxford American Dictionary defines it as “the loss of potential gain from other alternatives when one alternative is chosen.” Opportunity cost is a key concept in economics, and has been described as expressing “the basic relationship between scarcity and choice.”[2] The notion of opportunity cost plays a crucial part in attempts to ensure that scarce resources are used efficiently.[3]Opportunity costs are not restricted to monetary or financial costs: the real cost of output forgone, lost time, pleasure or any other benefit that provides utility should also be considered an opportunity cost.

Costs can take two forms: explicit costs and implicit costs.

Explicit costs are opportunity costs that involve direct monetary payment by producers. The explicit opportunity cost of the factors of production not already owned by a producer is the price that the producer has to pay for them. For instance, if a firm spends $100 on electrical power consumed, its explicit opportunity cost is $100.[5]This cash expenditure represents a lost opportunity to purchase something else with the $100.

Implicit costs (also called implied, imputed or notional costs) are the opportunity costs that are not reflected in cash outflow but implied by the failure of the firm to allocate its existing (owned) resources, or factors of production to the best alternative use. For example: a manufacturer has previously purchased 1000 tons of steel and the machinery to produce a widget. The implicit part of the opportunity cost of producing the widget is the revenue lost by not selling the steel and not renting out the machinery instead of using it for production.

Example: Suppose you bought two tickets for a total of $100 for a sold out sporting event. You will also spend $70 on gas/parking/food/etc. By going to the sporting event, you must call off of 8 hours of work where you make $10/hour. What is/are the explicit costs? What is/are the implicit costs?

Answer: The explicit cost is the total amount of money you actually paid. This is the $100 on the tickets and the $70 on the other goods. Thus, the explicit costs total $170. The implicit cost is what you gave up or sacrificed. This is going to work. By going to the sporting event, you did not go to work. Therefore, you missed 8 hours of work where you could have earned $80. Thus, the total implicit cost is $80. Note that you did not have to pay $80; instead, it was simply money you did not make (that you could have.)

Example: You have to decide whether to work tomorrow or go to a party with your friend. If you work, you will earn $200. What is the opportunity cost of going to work?

Answer: If you go to work, you will miss out on going to the party (since that is your next best option.) Therefore, the implicit cost here is non-monetary. The implicit cost is the enjoyment you would have received by going to the party.

Rationality and Marginal Decision-Making

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rationality#Economics

Rationality plays a key role and there are several strands to this.[14] Firstly, there is the concept of instrumentality—basically the idea that people and organizations are instrumentally rational—that is, adopt the best actions to achieve their goals. Secondly, there is an axiomatic concept that rationality is a matter of being logically consistent within your preferences and beliefs. Thirdly, people have focused on the accuracy of beliefs and full use of information—in this view, a person who is not rational has beliefs that don’t fully use the information they have.

One term that you will hear about a lot this semester is ‘marginal.’ Whether it is marginal benefit, marginal cost, marginal revenue, or marginal utility, this term is not going away. When we make decisions, we think incrementally. For instance, when looking to buy a new car, you typically set a price range. Let us say that you have found two cars: one costs $10,000 and the other costs $11,000. You will compare what additional features you get for the additional $1,000. At the same time, you are probably not going to decide between a $5,000 used Toyota Camry and a brand-new $325,000 Bentley Mulsanne. Again, we make decisions in increments.

Some examples of marginal variables are:

Marginal Utility (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marginal_utility):

In economics, the utility is the satisfaction or benefit derived by consuming a product; thus the marginal utility of a good or service is the change in the utility from an increase in the consumption of that good or service.

Marginal Cost(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marginal_cost):

In economics, marginal cost is the change in the total cost that arises when the quantity produced is incremented by one unit, that is, it is the cost of producing one more unit of a good.[1] Intuitively, the marginal cost at each level of production includes the cost of any additional inputs required to produce the next unit. At each level of production and time period being considered, marginal costs include all costs that vary with the level of production, whereas other costs that do not vary with production are considered fixed. For example, the marginal cost of producing an automobile will generally include the costs of labor and parts needed for the additional automobile and not the fixed costs of the factory that have already been incurred. In practice, marginal analysis is segregated into short and long-run cases, so that, over the long run, all costs (including fixed costs) become marginal.

Marginal Revenue (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marginal_revenue):

In microeconomics, marginal revenue is the additional revenue that will be generated by increasing product sales by one unit.[1][2][3][4][5] It can also be described as the unit revenue the last item sold has generated for the firm.[3][5]

Incentives

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incentive

An incentive is a contingent motivator.[1] Traditional incentives are extrinsic motivators which reward actions to yield a desired outcome. The effectiveness of traditional incentives has changed as the needs of Western society have evolved. While the traditional incentive model is effective when there is a defined procedure and goal for a task, Western society started to require a higher volume of critical thinkers, so the traditional model became less effective.[1] Institutions are now following a trend in implementing strategies that rely on intrinsic motivations rather than the extrinsic motivations that the traditional incentives foster.

Some examples of traditional incentives are letter grades in the formal school system and monetary bonuses for increased productivity in the workplace. Some examples of the promotion of intrinsic motivation are Google allowing their engineers to spend 20% of their work time exploring their own interests,[1] and the competency-based education system.

| Type of Incentive | Definition |

|---|---|

| Remunerative/Financial | are said to exist where an agent can expect some form of material reward – especially money – in exchange for acting in a particular way.[3] |

| Moral | are said to exist where a particular choice is widely regarded as the right thing to do, or as particularly admirable, or where the failure to act in a certain way is condemned as indecent. A person acting on a moral incentive can expect a sense of self-esteem, and approval or even admiration from his community; a person acting against a moral incentive can expect a sense of guilt, and condemnation or even ostracism from the community.[3] |

| Coercive | are said to exist where a person can expect that the failure to act in a particular way will result in physical force being used against them (or their loved ones) by others in the community – for example, by inflicting pain in punishment, or by imprisonment, or by confiscating or destroying their possessions.[3] |

Incentive structures, however, are notoriously more tricky than they might appear to people who set them up. Incentives do not only increase motivation, but they also contribute to the self-selection of individuals, as different people are attracted by different incentive schemes depending on their attitudes towards risk, uncertainty, competitiveness.[9] Human beings are both finite and creative; that means that the people offering incentives are often unable to predict all of the ways that people will respond to them. While the promotion of intrinsic motivation is sometimes is employed to avoid this uncertainty, using short term incentives can yield similar results.

For example, decision-makers in for-profit firms often must decide what incentives they will offer to employees and managers to encourage them to act in ways beneficial to the firm. But many corporate policies – especially of the “extreme incentive” variant popular during the 1990s – that aimed to encourage productivity have, in some cases, led to failures as a result of unintended consequences. For example, stock options were intended to boost CEO productivity by offering a remunerative incentive (profits from rising stock prices) for CEOs to improve company performance. But CEOs could get profits from rising stock prices either (1) by making sound decisions and reaping the rewards of a long-term price increase, or (2) by fudging or fabricating accounting information to give the illusion of economic success, and reaping profits from the short-term price increase by selling before the truth came out and prices tanked. The perverse incentives created by the availability of option (2) have been blamed for many of the falsified earnings reports and public statements in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Also there is the trade-off of short term gains at the expense of long term gains or even long term company survival. It is easy to plunder the assets of a previously successful company and show spectacular short term gains only to have the enterprise collapse after those responsible have gotten their incentives and left the organization or industry. Although long term incentives could be part of the incentive system, they have been abandoned in the past 20 years. An example of an organization that used long term incentive programs was Hughes Aircraft and was highly successful until the government forced its divestiture from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Recently there has been movement on adopting the benefit corporation or B-Corporation as a way to change the trend away from short term financial incentives to long term financial and non-financial incentives.[10]

Not all for-profit companies used short term financial incentives at levels below the president or very top executive levels. The trend to move financial incentives down the organization hierarchy started in the 1980s as a way to boost what was considered low productivity. Prior to that time the incentives were associated more with customer satisfaction and producing high-quality products. Moving financial incentives down the corporate chain had the unintended consequences of subverting internal processes to save short term costs, forcing obsolescence at the lower levels as investment was deferred or abandoned, and lowering quality. Some of these issues are explored in the British documentary The Trap. This idea of financial incentives and pushing them to the lowest level common denominator has led to a new company structure or organizational ecology where essentially everything is a standalone profit center with the only incentive being short term financial incentives.

1.3 The Market

Trade

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods or services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. A system or network that allows trade is called a market.

Trade is meaningful because it is a mutual agreement. We do not voluntarily enter into a trade if we believe it will make us worse off. You will not always be made better off, as we take risks anytime we enter into a trade, but we believe that, on average, we will make ourselves better off.

Trade exists due to specialization and the division of labor, a predominant form of economic activity in which individuals and groups concentrate on a small aspect of production, but use their output in trades for other products and needs.[2]Trade exists between regions because different regions may have a comparative advantage (perceived or real) in the production of some trade-able commodity—including the production of natural resources scarce or limited elsewhere, or because different regions’ sizes may encourage mass production.[3] In such circumstances, trade at market prices between locations can benefit both locations.

We will discuss trade-in more depth in chapter 2.

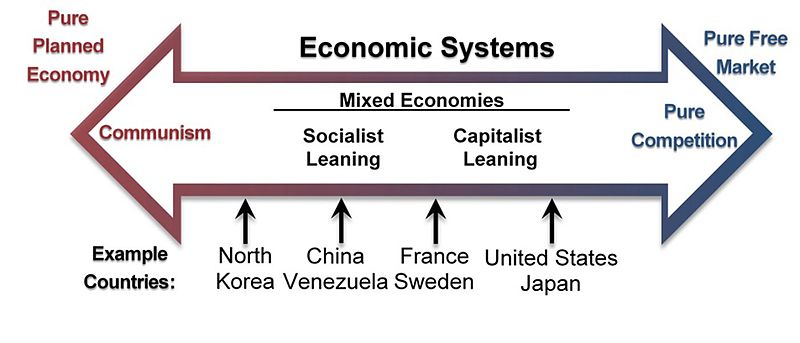

Types of Markets (Economies)

Planned economies

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planned_economy)

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment and the allocation of capital goods take place according to economy-wide economic and production plans.

Planned economies are usually associated with Soviet-type central planning, which involves centralized state planning and administrative decision-making.[5] In command economies, important allocation-decisions are made by government authorities and are imposed by law.[6] Planned economies contrast with unplanned economies, specifically market economies, where autonomous firms operating in markets make decisions about production, distribution, pricing, and investment. Market economies that use indicative planning are sometimes referred to[by whom?] as “planned market economies”.

The traditional conception of socialism involves the integration of socially-owned economic enterprises via some form of planning with direct calculation substituting factor markets. As such, the concept of a planned economy is often associated[by whom?] with socialism and with socialist planning.[7][8][9] More recent approaches to socialist planning and allocation have come from some economists and computer scientists proposing planning mechanisms based on advances in computer science and information technology.[10]

Market economies

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Market_economy)

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production, and distribution are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand. The major characteristic of a market economy is the existence of factor markets that play a dominant role in the allocation of capital and the factors of production.[1][2]

Market economies range from minimally regulated “free market” and laissez-faire systems—where state activity is restricted to providing public goods and services and safeguarding private ownership[3]—to interventionist forms where the government plays an active role in correcting market failures and promoting social welfare. State-directed or dirigist economies are those where the state plays a directive role in guiding the overall development of the market through industrial policies or indicative planning—which guides but does not substitute the market for economic planning—a form sometimes referred to as a mixed economy.[4][5][6]

Market economies are contrasted with planned economies where investment and production decisions are embodied in an integrated economy-wide economic plan by a single organizational body that owns and operates the economy’s means of production.

Rationing

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rationing

Because society can only produce so much with our scarce resources, we must ration.

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, or services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one’s allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular day or at a particular time. There are many forms of rationing, and in western civilization, people experience some of them in daily life without realizing it.[1]

Rationing is often done to keep the price below the equilibrium (market-clearing) price determined by the process of supply and demand in an unfettered market. Thus, rationing can be complementary to price controls. An example of rationing in the face of rising prices took place in the various countries where there was rationing of gasoline during the 1973 energy crisis.

A reason for setting the price lower than would clear the market may be that there is a shortage, which would drive the market price very high. High prices, especially in the case of necessities, are undesirable with regard to those who cannot afford them. Traditionalist economists argue, however, that high prices act to reduce waste of the scarce resource while also providing an incentive to produce more.

Rationing using ration stamps is only one kind of non-price rationing. For example, scarce products can be rationed using queues. This is seen, for example, at amusement parks, where one pays a price to get in and then need not pay any price to go on the rides. Similarly, in the absence of road pricing, access to roads is rationed in a first-come, first-served queueing process, leading to congestion.

Authorities which introduce rationing often have to deal with the rationed goods being sold illegally on the black market.

Rationing has been instituted during wartime for civilians. For example, each person may be given “ration coupons” allowing him or her to purchase a certain amount of a product each month. Rationing often includes food and other necessities for which there is a shortage, including materials needed for the war effort such as rubber tires, leather shoes, clothing, and fuel.

Rationing of food and water may also become necessary during an emergency, such as a natural disaster or terror attack. In the U.S., the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has established guidelines for civilians on rationing food and water supplies when replacements are not available. According to FEMA standards, every person should have a minimum of 1 US quart (0.95 L) per day of water, and more for children, nursing mothers and the ill.[2]

Free Markets Work Well…Most of the Time

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invisible_hand and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spontaneous_order

The invisible hand is a term used by Adam Smith to describe the unintended social benefits of an individual’s self-interested actions.[citation needed] The phrase was employed by Smith with respect to income distribution (1759) and production (1776). The exact phrase is used just three times in Smith’s writings but has come to capture his notion that individuals’ efforts to pursue their own interest may frequently benefit society more than if their actions were directly intending to benefit society.

The idea of trade and market exchange automatically channeling self-interest toward socially desirable ends is a central justification for the laissez-faire economic philosophy, which lies behind neoclassical economics.[3] In this sense, the central disagreement between economic ideologies can be viewed as a disagreement about how powerful the “invisible hand” is. In alternative models, forces which were nascent during Smith’s lifetime, such as large-scale industry, finance, and advertising, reduce its effectiveness.[4]

Spontaneous order, also named self-organization in the hard sciences, is the spontaneous emergence of order out of seeming chaos. It is a process in social networks including economics, though the term “self-organization” is more often used for physical changes and biological processes, while “spontaneous order” is typically used to describe the emergence of various kinds of social orders from a combination of self-interested individuals who are not intentionally trying to create order through planning. The evolution of life on Earth, language, crystal structure, the Internet and a free market economy have all been proposed as examples of systems which evolved through spontaneous order.[1]

Spontaneous orders are to be distinguished from organizations. Spontaneous orders are distinguished by being scale-free networks, while organizations are hierarchical networks. Further, organizations can be and often are a part of spontaneous social orders, but the reverse is not true. Further, while organizations are created and controlled by humans, spontaneous orders are created, controlled, and controllable by no one.[citation needed] In economics and the social sciences, spontaneous order is defined as “the result of human actions, not of human design”.[2]

Spontaneous order is an equilibrium behavior between self-interested individuals, which is most likely to evolve and survive, obeying the natural selection process “survival of the likeliest”.[3]

Many economic classical liberals, such as Hayek, have argued that market economies are a spontaneous order, “a more efficient allocation of societal resources than any design could achieve.”[7] They claim this spontaneous order (referred to as the extended order in Hayek’s The Fatal Conceit) is superior to any order a human mind can design due to the specifics of the information required.[8] Centralized statistical data cannot convey this information because the statistics are created by abstracting away from the particulars of the situation.[9]

In a market economy, price is the aggregation of information acquired when the people who own resources are free to use their individual knowledge. Price then allows everyone dealing in a commodity or its substitutes to make decisions based on more information than he or she could personally acquire, information not statistically conveyable to a centralized authority. Interference from a central authority which affects price will have consequences they could not foresee because they do not know all of the particulars involved.

According to Barry, this is illustrated in the concept of the invisible hand proposed by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations.[1] Thus in this view by acting on information with greater detail and accuracy than possible for any centralized authority, a more efficient economy is created to the benefit of a whole society.

Lawrence Reed, president of the Foundation for Economic Education, describes spontaneous order as follows:

Spontaneous order is what happens when you leave people alone—when entrepreneurs… see the desires of people… and then provide for them.

They respond to market signals, to prices. Prices tell them what’s needed and how urgently and where. And it’s infinitely better and more productive than relying on a handful of elites in some distant bureaucracy.[10]

Government Can Fix (Some) Market Failures

The government can, in the broadest of terms, improve market outcomes in the following three ways:

- The government can create and enforce rules to protect institutions.

- The government can promote efficiency in order to minimize market failures.

- The government can promote equity by creating policies to reduce gaps in economic well-being.

- The government can correct macroeconomic issues through the use of fiscal policy.

Property rights will be discussed in the next pillar, but let us look at efficiency and equity first.

Equity

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equity_(economics)

Equity or economic equality is the concept or idea of fairness in economics, particularly in regard to taxation or welfare economics. More specifically, it may refer to equal life chances regardless of identity, to provide all citizens with a basic and equal minimum of income, goods, and services or to increase funds and commitment for redistribution.[1]

Inequality and inequities have significantly increased in recent decades, possibly driven by the worldwide economic processes of globalization, economic liberalization, and integration.[2] This has led to states ‘lagging behind’ on headline goals such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and different levels of inequity between states have been argued to have played a role in the impact of the global economic crisis of 2008–2009.[2]

Equity is based on the idea of moral equality.[2] Equity looks at the distribution of capital, goods, and access to services throughout an economy and is often measured using tools such as the Gini index. Equity may be distinguished from economic efficiency in the overall evaluation of social welfare. Although ‘equity’ has broader uses, it may be posed as a counterpart to economic inequality in yielding a “good” distribution of wealth. It has been studied in experimental economics as inequity aversion. Low levels of equity are associated with life chances based on inherited wealth, social exclusion and the resulting poor access to basic services and intergenerational poverty resulting in a negative effect on growth, financial instability, crime, and increasing political instability.[2]

The state often plays a central role in the necessary redistribution required for equity between all citizens, but applying this in practice is highly complex and involves contentious choices.

Efficiency

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Productive_efficiency

Productive efficiency is a situation in which the economy could not produce any more of one good without sacrificing the production of another good. In other words, productive efficiency occurs when a good or service is produced at the lowest possible cost. The concept is illustrated on a production possibility frontier (PPF), where all points on the curve are points of productive efficiency.[1] An equilibrium may be productively efficient without being allocatively efficient— i.e. it may result in a distribution of goods where social welfare is not maximized. It is one type of economic efficiency.

Productive efficiency requires that all firms operate using best-practice technological and managerial processes. By improving these processes, an economy or business can extend its production possibility frontier outward, so that efficient production yields more output than previously.

Productive inefficiency, with the economy operating below its production possibilities frontier, can occur because the productive inputs physical capital and labor are underutilized—that is, some capital or labor is left sitting idle—or because these inputs are allocated in inappropriate combinations to the different industries that use them.

Due to the nature and culture of monopolistic companies, they may not be productively efficient because of X-inefficiency, whereby companies operating in a monopoly have less of an incentive to maximize output due to lack of competition. However, due to economies of scale, it can be possible for the profit-maximizing level of output of monopolistic companies to occur with a lower price to the consumer than perfectly competitive companies.

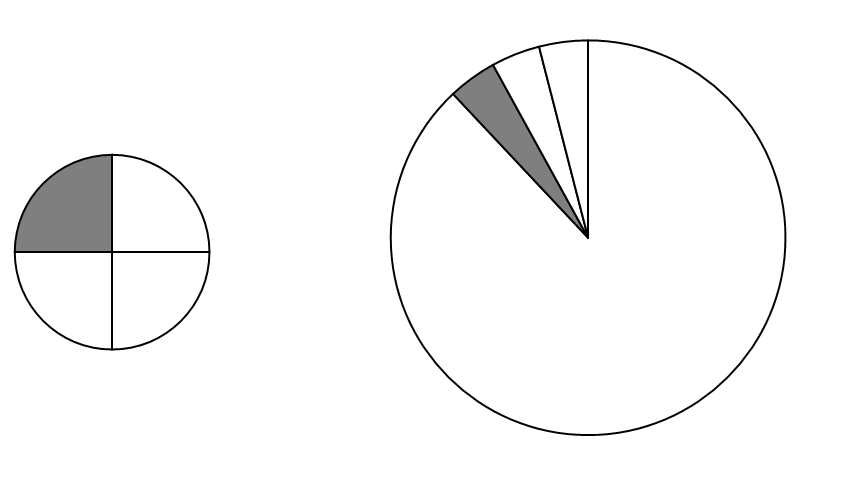

The Trade-off Between Efficiency and Equity

One issue that the modern economy faces is that of uneven economic growth. As the world continues to grow, some people, countries, and groups grow slower than others. When that growth is compounding over many years, the difference becomes staggering. Therefore, the following trade-off persist. If we promote policies focused on equity, we need to remove resources from the most successful and redistribute them to the least successful. But this is removing resources from those that are able to do the most with them. On the other hand, policies that are only concerned with efficiency allow for increasing inequality which also poses its own threat to the economy.

As an analogy, we can think of economics as the size of a pie and equity as the distribution of the pie.

1.4 Introductory Wrap-up

Economics as a Social Science

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_method

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is an empirical method of knowledge acquisition which has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century. It involves careful observation, which includes rigorous skepticism about what is observed, given that cognitive assumptions about how the world works influence how one interprets a percept. It involves formulating hypotheses, via induction, based on such observations; experimental and measurement-based testing of deductions drawn from the hypotheses; and refinement (or elimination) of the hypotheses based on the experimental findings. These are principles of the scientific method, as opposed to a definitive series of steps applicable to all scientific enterprises.[1][2][3]

How Economists (Try to) Use the Scientific Method

(From: https://openstax.org/details/books/principles-microeconomics-2e)

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), one of the greatest economists of the twentieth century, pointed out that economics is not just a subject area but also a way of thinking. Keynes famously wrote in the introduction to a fellow economist’s book: “[Economics] is a method rather than a doctrine, an apparatus of the mind, a technique of thinking, which helps its possessor to draw correct conclusions.” In other words, economics teaches you how to think, not what to think.

Economists see the world through a different lens than anthropologists, biologists, classicists, or practitioners of any other discipline. They analyze issues and problems using economic theories that are based on particular assumptions about human behavior. These assumptions tend to be different than the assumptions an anthropologist or psychologist might use. A theory is a simplified representation of how two or more variables interact with each other. The purpose of a theory is to take a complex, real-world issue and simplify it down to its essentials. If done well, this enables the analyst to understand the issue and any problems around it. A good theory is simple enough to understand, while complex enough to capture the key features of the object or situation you are studying.

Sometimes economists use the term model instead of theory. Strictly speaking, a theory is a more abstract representation, while a model is a more applied or empirical representation. We use models to test theories, but for this course we will use the terms interchangeably.

For example, an architect who is planning a major office building will often build a physical model that sits on a tabletop to show how the entire city block will look after the new building is constructed. Companies often build models of their new products, which are more rough and unfinished than the final product, but can still demonstrate how the new product will work.

Economists carry a set of theories in their heads like a carpenter carries around a toolkit. When they see an economic issue or problem, they go through the theories they know to see if they can find one that fits. Then they use the theory to derive insights about the issue or problem. Economists express theories as diagrams, graphs, or even as mathematical equations. (Do not worry. In this course, we will mostly use graphs.) Economists do not figure out the answer to the problem first and then draw the graph to illustrate. Rather, they use the graph of the theory to help them figure out the answer. Although at the introductory level, you can sometimes figure out the right answer without applying a model, if you keep studying economics, before too long you will run into issues and problems that you will need to graph to solve. We explain both micro and macroeconomics in terms of theories and models. The most well-known theories are probably those of supply and demand, but you will learn a number of others.

Realism versus Understanding

As with many concepts, what you are taught in this class is incomplete. That does not mean it is incorrect; rather, it simply means that we will be excluding pieces of the story. This is done because economists face a trade-off between realism and understanding. What this means is that the more realistic a model is, the more complex it is. On the other hand, if we try to make a model easier to understand, we accomplish this by simplifying certain components therefore making it less realistic (but again, not incorrect.)

For example, say we want to investigate the role of a price increase in the quantity of gasoline purchased. For our purposes, we are interested in the fact that the law of demand would say that an increase in the price of gas will reduce the consumption of gasoline. But in reality, there are other factors at play. For instance, how will an increase in the price of gas impact the availability of alternative fuels (and how will their availability impact the price and consumption of gasoline)? In reality, a change in the price of one good will have impacts on many, many other goods and those impacts have the ability to influence the original good. But, we need not worry about it. Instead, our goal is to study the main relationships, so we simply ignore the other components. If you progress further through the economics courses, you will start to move from understanding to realism.

Ceteris Paribus

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceteris_paribus

Ceteris paribus or caeteris paribus is a Latin phrase meaning “other things equal”. English translations of the phrase include “all other things being equal” or “other things held constant” or “all else unchanged“. A prediction or a statement about a causal, empirical, or logical relation between two states of affairs is ceteris paribusif it is acknowledged that the prediction, although usually accurate in expected conditions, can fail or the relation can be abolished by intervening factors.[1]

A ceteris paribus assumption is often key to scientific inquiry, as scientists seek to screen out factors that perturb a relation of interest. Thus, epidemiologists for example may seek to control independent variables as factors that may influence dependent variables—the outcomes or effects of interest. Likewise, in scientific modeling, simplifying assumptions permit illustration or elucidation of concepts thought relevant within the sphere of inquiry.

There is ongoing debate in the philosophy of science concerning ceteris paribus statements. On the logical empiricist view, fundamental physics tends to state universal laws, whereas other sciences, such as biology, psychology, and economics, tend to state laws that hold true in normal conditions but have exceptions, ceteris paribuslaws (cp laws).[2] The focus on universal laws is a criterion distinguishing fundamental physics as fundamental science, whereas cp laws are predominant in most other sciences as special sciences, whose laws hold in special cases.[2] This distinction assumes a logical empiricist view of science. It does not readily apply in a mechanistic understanding of scientific discovery. There is reasonable disagreement as to whether mechanisms or laws are the appropriate models, though mechanisms are the favored method.[3]

One of the disciplines in which ceteris paribus clauses are most widely used is economics, in which they are employed to simplify the formulation and description of economic outcomes. When using ceteris paribus in economics, one assumes that all other variables except those under immediate consideration are held constant. For example, it can be predicted that if the price of beef increases—ceteris paribus—the quantity of beef demanded by buyers will decrease. In this example, the clause is used to operationally describe everything surrounding the relationship between both the price and the quantity demanded of an ordinary good.

This operational description intentionally ignores both known and unknown factors that may also influence the relationship between price and quantity demanded, and thus to assume ceteris paribus is to assume away any interference with the given example. Such factors that would be intentionally ignored include: a change in the price of substitute goods, (e.g., the price of pork or lamb); a change in the level of risk aversion among buyers (e.g., due to an increase in the fear of mad cow disease); and a change in the level of overall demand for a good regardless of its current price (e.g., a societal shift toward vegetarianism).

The clause is often loosely translated as “holding all else constant.” It does not imply that no other things will in fact change; rather, it isolates the effect of one particular change.

Making Economic Statements

Positive Economic Statements

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Positive_economics

Positive economics (as opposed to normative economics) is the branch of economics that concerns the description and explanation of economic phenomena.[1] It focuses on facts and cause-and-effect behavioral relationships and includes the development and testing of economics theories.[2] An earlier term was value-free (German: wertfrei) economics.

Positive economics as science, concerns analysis of economic behavior.[3] A standard theoretical statement of positive economics as operationally meaningful theorems is in Paul Samuelson‘s Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947). Positive economics as such avoids economic value judgments. For example, a positive economic theory might describe how money supply growth affects inflation, but it does not provide any instruction on what policy ought to be followed.

Still, positive economics is commonly deemed necessary for the ranking of economic policies or outcomes as to acceptability,[1] which is normative economics. Positive economics is sometimes defined as the economics of “what is”, whereas normative economics discusses “what ought to be”. The distinction was exposited by John Neville Keynes (1891)[4] and elaborated by Milton Friedman in an influential 1953 essay.[5]

Positive economics concerns what is. To illustrate, an example of a positive economic statement is as follows: “The unemployment rate in France is higher than that in the United States.”

Normative Economic Statements

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Normative_economics

Normative economics (as opposed to positive economics) is a part of economics that expresses value or normative judgments about economic fairness or what the outcome of the economy or goals of public policy ought to be.[1]

Economists commonly prefer to distinguish normative economics (“what ought to be” in economic matters) from positive economics (“what is”). Many normative (value) judgments, however, are held conditionally, to be given up if facts or knowledge of facts changes, so that a change of values may be purely scientific.[2] On the other hand, welfare economist Amartya Sen distinguishes basic (normative) judgments, which do not depend on such knowledge, from nonbasic judgments, which do. He finds it interesting to note that “no judgments are demonstrably basic” while some value judgments may be shown to be nonbasic. This leaves open the possibility of fruitful scientific discussion of value judgments.[3]

Positive and normative economics are often synthesized in the style of practical idealism. In this discipline, sometimes called the “art of economics,” positive economics is utilized as a practical tool for achieving normative objectives.

An example of a normative economic statement is as follows:

-

- The price of milk should be $6 a gallon to give dairy farmers a higher living standard and to save the family farm.

This is a normative statement because it reflects value judgments. This specific statement makes the judgment that farmers deserve a higher living standard and that family farms ought to be saved.[1]

Subfields of normative economics include social choice theory, cooperative game theory, and mechanism design.

Some earlier technical problems posed in welfare economics and the theory of justice have been sufficiently addressed as to leave room for consideration of proposals in applied fields such as resource allocation, public policy, social indicators, and inequality and poverty measurement.[4]

Examples

- The government should provide healthcare to all of its citizens.

- If the government provides healthcare, total healthcare expenditures will increase.

- Higher interest rates will increase home purchases.

- Penn State Behrend should ban tobacco on its entire campus.

- Pennsylvania should raise its minimum wage to $15 per hour.

- A car scrapping rebate will reduce the price of used cars.

- Normative. This is an opinion. There is nothing to test.

- Positive. If the government begins to provide healthcare we could compare expenditures before and after the change in healthcare provision to determine whether the statement is true or false.

- Positive. This statement is false, but it is still testable. When interest rates increase, it makes getting a loan more expensive. This is part of the cause of the housing market failure leading up to 2008. But none of that matters to this question. We can see that when interest rates go up, housing sales fall. So we can state that the above statement is false. Whenever we can state whether something is true or false, it is positive (regardless of the answer.)

- Normative. This is an opinion. There is nothing to test.

- Normative. This is also an opinion. If the statement were “raising minimum wage to $15/hour would increase employment,” then the statement would be positive. But, in the given statement, there is nothing to test.

- Positive. This was actually done in 2008 in a program called Cash for Clunkers. This ended up increasing the price of used cars because many of them (the fuel inefficient ones) were taken off the road. A lower supply means a higher price. But, like #3, this does not matter. We can state whether the statement would be true or false, thereby making it a positive statement.

Microeconomics versus Macroeconomics

Microeconomics

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microeconomics

Microeconomics (from Greek prefix mikro- meaning “small” + economics) is a branch of economics that studies the behaviour of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms.[1][2][3]

One goal of microeconomics is to analyze the market mechanisms that establish relative prices among goods and services and allocate limited resources among alternative uses. Microeconomics shows conditions under which free markets lead to desirable allocations. It also analyzes market failure, where markets fail to produce efficient results.

Microeconomics stands in contrast to macroeconomics, which involves “the sum total of economic activity, dealing with the issues of growth, inflation, and unemployment and with national policies relating to these issues”.[2] Microeconomics also deals with the effects of economic policies (such as changing taxation levels) on the aforementioned aspects of the economy.[4] Particularly in the wake of the Lucas critique, much of modern macroeconomic theory has been built upon microfoundations—i.e. based upon basic assumptions about micro-level behavior.

Macroeconomics

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics (from the Greek prefix makro- meaning “large” + economics) is a branch of economics dealing with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole. This includes regional, national, and global economies.[1][2]

Macroeconomists study aggregated indicators such as GDP, unemployment rates, national income, price indices, and the interrelations among the different sectors of the economy to better understand how the whole economy functions. They also develop models that explain the relationship between such factors as national income, output, consumption, unemployment, inflation, savings, investment, international trade, and international finance.

While macroeconomics is a broad field of study, there are two areas of research that are emblematic of the discipline: the attempt to understand the causes and consequences of short-run fluctuations in national income (the business cycle), and the attempt to understand the determinants of long-run economic growth (increases in national income). Macroeconomic models and their forecasts are used by governments to assist in the development and evaluation of economic policy.

Macroeconomics and microeconomics, a pair of terms coined by Ragnar Frisch, are the two most general fields in economics.[3] In contrast to macroeconomics, microeconomics is the branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions and the interactions among these individuals and firms in narrowly-defined markets.