Chapter 13: The Endocrine System

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the learner should be able to:

- Explain the function of the pancreas.

- Describe the function of insulin.

- Define diabetes mellitus.

- Discuss the differences between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- Discuss pathophysiological effects of diabetes mellitus.

- List the risk factors for and signs and symptoms of diabetes mellitus.

- Discuss the treatment of diabetes mellitus.

- Define insulin shock and ketoacidosis.

- Discuss the role of the PTA in the treatment and control of diabetes.

- Discuss the importance of education of patients and family members about risk factors, potential complications, treatments, and the importance of diet, exercise, and maintenance of appropriate blood sugar levels.

- Discuss the function and normal secretions of the pituitary, thyroid, parathyroid, and adrenal glands.

- Identify disorders associated with hypo/hyper functions of each of the above glands.

- Discuss metabolic disorders, focusing on causes, effects, complications, and management.

- Cushing’s disease

- Addison’s disease

- Thyroid conditions

- Pituitary conditions

Chapter Contents

- 13.1 Diabetes Mellitus

- 13.2 Cushing Disease

- 13.3 Addison Disease

- 13.4 Thyroid Conditions

- 13.5 Pituitary Conditions

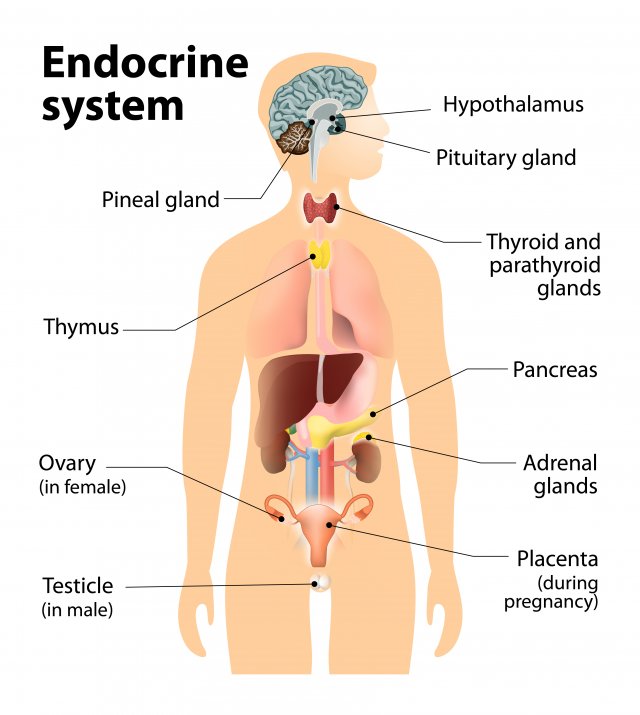

- Hypothalamus

- Pituitary gland (hypophysis)

- Adrenal glands (2)

- Thyroid gland

- Parathyroid glands (4)

- Pancreas

- Gonads (2)

Each of the glands or organs involved in the endocrine system secretes one or more hormones which help regulate metabolism and other body functions.

Long Description

Title: Endocrine system

An illustration of the human body shows internal organs. The following parts of the illustration are labelled:

- Pineal gland: points to the base of the brain

- Thymus: points to upper chest

- Ovary (in female): points to groin

- Testicle (in male): points to groin

- Hypothalamus: points to the base of the brain

- Pituitary gland: points to the base of the brain

- Thyroid and parathyroid glands: points to the throat

- Pancreas: points to mid torso

- Adrenal glands: points to mid torso

- Placenta (during pregnancy): points to groin

In general terms, endocrine glands or organs produce and secrete hormones. The hormones circulate through the blood stream until they encounter target cells. They enter their target cells perform their function. Excess hormones or waste products from their metabolism travel through the circulatory system and are metabolized by the liver. From there, they travel to the kidney for processing for excretion from the body.

Hormone levels in the body are controlled by negative feedback loops. That is, if the circulating hormone levels are too high, hormone production and release diminish. If circulating hormones are deficient, secretion from endocrine glands increases. Often, two or more hormones work in an antagonistic relationship, as one hormone might increase production of a substance, while a different hormone decreases the production of the substance. We see this in diabetes. When the hormone, insulin, is produced and used by cells, blood glucose levels drop, stimulating the pancreas to release a different hormone, glucagon, causes the liver to release stored glucose, which raises blood glucose to normal levels. In diabetes, insulin production and usage are impaired, so the glucose levels in the blood remain high (hyperglycemia).

The timing of hormone production and release varies according to the function of the hormone. For example, in females, estrogen production increases and decreases with a woman’s monthly cycle and increased dramatically during pregnancy. Many hormones remain at fairly constant levels all the time, and only in clinical cases of hyper- or hypo-function do we see dramatic changes in hormone levels.

In this chapter, we will discuss a few of the most common endocrine disorders.

13.1 Diabetes Mellitus

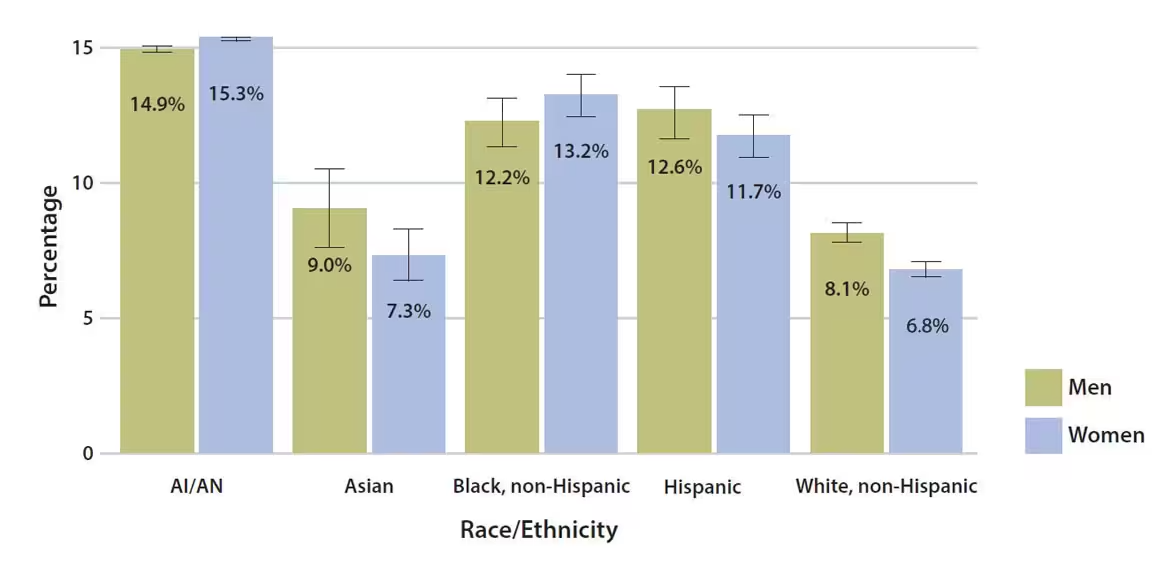

Long Description

Title: Estimated age-adjusted prevalence of diagnosed diabetes by race/ethnicity and sex among adults aged 18 and older, United States, 2013–2015

American Indian/Alaska Native

Men: 14.9%

Women: 15.3%

Asian

Men: 9.0%

Women: 7.3%

Black, non-Hispanic

Men: 12.2%

Women: 13.2%

Hispanic

Men: 12.6%

Women: 11.7%

White, non-Hispanic

Men: 8.1%

Women: 6.8%

Note: Error bars represent upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval.

Data source: 2013–2015 National Health Interview Survey, except American Indian/Alaska Native data, which are from the 2015 Indian Health Service National Data Warehouse.

Diabetes mellitus (DM), especially type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM-2), is a disease that is increasingly common throughout the world, and particularly in the United States. According to the CDC, more than 100 million people in the United States have diabetes. The demographic breakdown of gender and ethnicity can be appreciated in the chart below.

Read the text and watch the videos on diabetes mellitus presented by Khan Academy. There are many different videos and readings available on this website. All are useful. The ones on Pathophysiology might be most useful for this class.

Work through the following activities to reinforce your understanding of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Case StudyA.B. is a retired 69-year-old man with a 5-year history of type 2 diabetes. He had symptoms indicating hyperglycemia for 2 years before diagnosis. He had fasting blood glucose records indicating values of 118–127 mg/dl, which were described to him as indicative of “borderline diabetes.” He also remembered past episodes of nocturia associated with large pasta meals and Italian pastries. At the time of initial diagnosis, he was advised to lose weight (“at least 10 lb.”), but no further action was taken.

Referred by his family physician to the diabetes specialty clinic, A.B. presents with recent weight gain, suboptimal diabetes control, and foot pain. He has been trying to lose weight and increase his exercise for the past 6 months without success.

A.B. also takes atorvastatin (Lipitor), 10 mg daily, for hypercholesterolemia (elevated LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated triglycerides). He has tolerated this medication and adheres to the daily schedule.

He does not test his blood glucose levels at home and expresses doubt that this procedure would help him improve his diabetes control. “What would knowing the numbers do for me?,” he asks. “The doctor already knows the sugars are high.”

A.B. states that he has “never been sick a day in my life.” He recently sold his business and has become very active in a variety of volunteer organizations. He lives with his wife of 48 years and has two married children. Although both his mother and father had type 2 diabetes, A.B. has limited knowledge regarding diabetes self-care management and states that he does not understand why he has diabetes since he never eats sugar. In the past, his wife has encouraged him to treat his diabetes with herbal remedies and weight-loss supplements, and she frequently scans the Internet for the latest diabetes remedies.

During the past year, A.B. has gained 22 lb. Since retiring, he has been more physically active, playing golf once a week and gardening, but he has been unable to lose more than 2–3 lb. He has never seen a dietitian and has not been instructed in self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG).

A.B.’s diet history reveals excessive carbohydrate intake in the form of bread and pasta. His normal dinners consist of 2 cups of cooked pasta with homemade sauce and three to four slices of Italian bread. During the day, he often has “a slice or two” of bread with butter or olive oil. He also eats eight to ten pieces of fresh fruit per day at meals and as snacks. He prefers chicken and fish, but it is usually served with a tomato or cream sauce accompanied by pasta. His wife has offered to make him plain grilled meats, but he finds them “tasteless.” He drinks 8 oz. of red wine with dinner each evening. He stopped smoking more than 10 years ago, he reports, “when the cost of cigarettes topped a buck-fifty.”

The medical documents that A.B. brings to this appointment indicate that his hemoglobin A1c (A1C) has never been <8%. His blood pressure has been measured at 150/70, 148/92, and 166/88 mmHg on separate occasions during the past year at the local senior center screening clinic. Although he was told that his blood pressure was “up a little,” he was not aware of the need to keep his blood pressure ≤130/80 mmHg for both cardiovascular and renal health.

A.B. has never had a foot exam as part of his primary care exams, nor has he been instructed in preventive foot care. However, his medical records also indicate that he has had no surgeries or hospitalizations, his immunizations are up to date, and, in general, he has been remarkably healthy for many years.

(Case reported adapted from American Diabetes Association: Case Study)

Name at least 3 areas of concern for this patient.

Which ones could PT best address?

Name some possible adverse outcomes for this patient if nothing changes in the management of his diabetes.

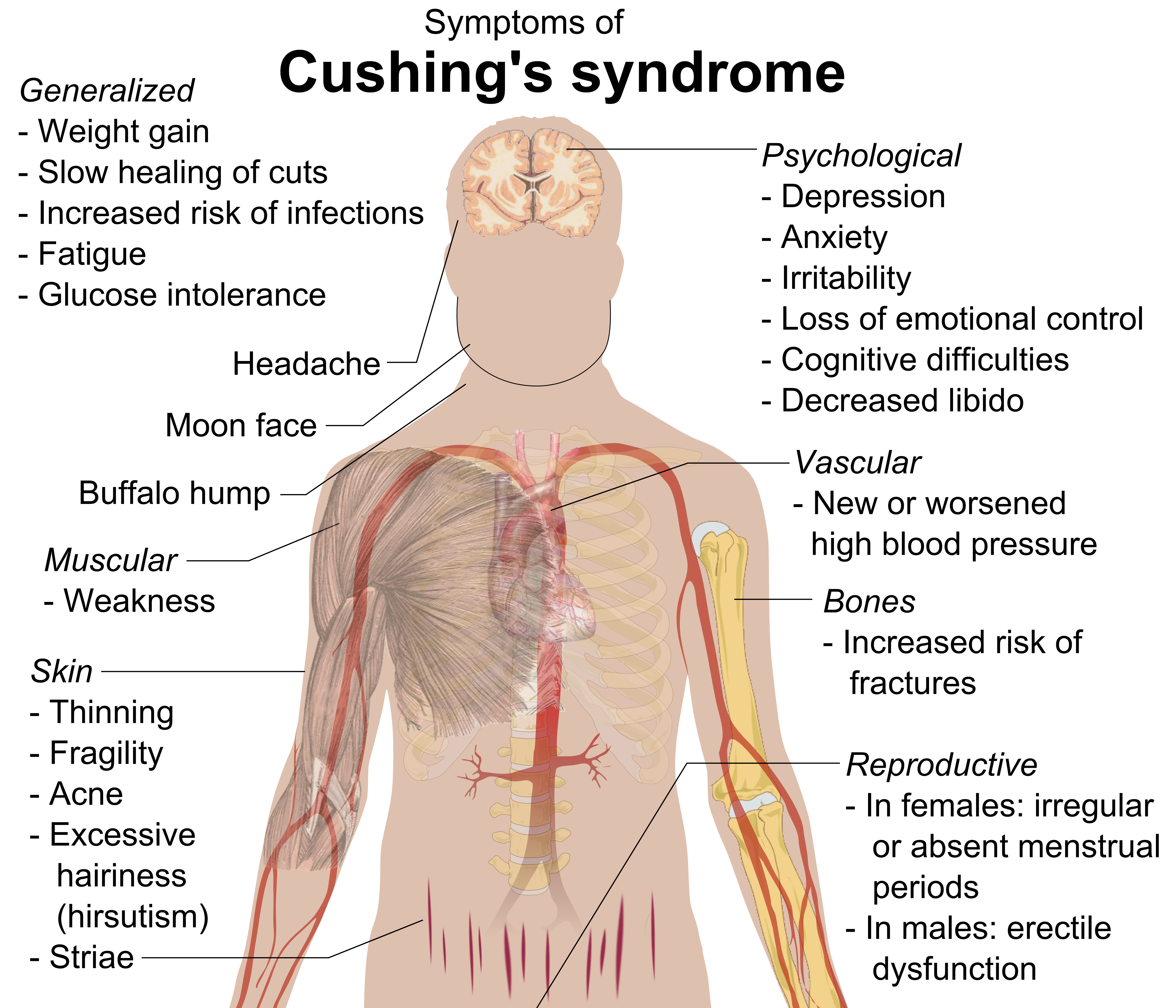

13.2 Cushing Disease and Cushing Syndrome (Adrenal glands/ pituitary gland/ hypothalamus)

Cushing disease is caused by a pituitary gland tumor (usually benign) that over-secretes the hormone ACTH, thus overstimulating the adrenal glands’ cortisol production. Cushing syndrome refers to the signs and symptoms associated with excess cortisol in the body, regardless of the cause. Cushing syndrome can be caused by endogenous or exogenous problems. Endogenous causes include adenoma (tumor) on the pituitary gland, adenoma on the adrenal gland, and tumors that produce cortisol elsewhere in the body, often small cell carcinoma in the lung. Exogenous causes include long term use of steroidal medications (e.g. prednisone, hydrocortisone) for autoimmune disease, or other chronic illness. These medications act as cortisol in the body, so the signs and symptoms of the conditions relate to the excessive cortisol levels. Signs and symptoms of Cushing syndrome are: hypertension, hyperglycemia, hirsutism, round, moon-shaped face, excess fat in the abdomen and trunk, buffalo hump on the back, high blood pressure, fluid retention and weight gain, osteoporosis and easily fractured bones, and thin skin with wounds and sores that are slow to heal. The arms and legs often appear thin and frail, while the trunk is full and round. Purple striae often appear on the trunk, and sometimes on the face, resulting from sudden weight gain and skin stretch.

Long Description

Title: Symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome

An illustration of the body is transparent and shows the brain, muscles, heart, bones and blood vessels. Symptoms are listed below. They have arrows pointing to the parts of the body they affect.

On the left side of the body:

Generalized

- Weight gain

- Slow healing of cuts

- Increased risk of infections

- Fatigue

- Glucose intolerance

Headache: points to headMoon face: points to cheeks

Buffalo hump: points to neck

Muscular: point to muscles in shoulder

- Weakness

Skin: points to surface of arm

- Thinning

- Fragility

- Acne

- Excessive hairiness (hirsutism)

Striae: point to lower abdomen

On the right side of the body:

Psychological: points to brain

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Loss of emotional control

- Cognitive difficulties

- Decreased libido

Vascular: points to heart

- New or worsened high blood pressure

Bones: points to humerus

- Increased risk of fractures

Reproductive: points to groin

- In females: Irregular or absent menstrual periods

- In males: Erectile dysfunction

The treatment for Cushing syndrome depends upon the etiology. If exogenous steroids are the source of the condition, they need to be tapered slowly and replaced by other medications. The tapering must be done slowly, as the adrenal glands have been in a state of hypofunction due to the exogenous steroids in the body. If the steroid medications are removed suddenly, there will not be enough cortisol, and the patient’s blood pressure could drop dramatically, and the patient could die. This sudden drop in blood pressure associated with too little cortisol is call an Addisonian crisis. If the cause of Cushing syndrome is endogenous (tumor), the tumor needs to be surgically removed, and/or treated with radiation or chemotherapy. The patient will most likely require life-long hormone replacement therapy.

Wikipedia page for Cushing’s Syndrome

13.3 Addison Disease (Adrenal glands/pituitary gland/hypothalamus)

Addison disease is really the opposite of Cushing syndrome. In the case of Addison disease, there is too little cortisol in the body. This condition is most often caused by immune system dysfunction (autoimmune adrenalitis) or infection, or by other problems, such as tumors on the adrenal glands, pituitary gland, or hypothalamus. The signs and symptoms of Addison disease include: weight loss, dehydration, decreased blood pressure, hypoglycemia, increased skin pigmentation, abdominal pain, and generalized weakness. If left untreated, an Addisonian crisis will occur, with a loss of blood pressure, resulting in death. This condition can be managed through life-long hormone replacement therapy (steroids). There is no cure for Addison disease, but a person with Addison disease can lead a relatively normal life. They will need increased steroids if they are in any kind of stressful situation, such as hospitalization, surgery, infection, or emotional stress.

For a video explanation of Addison disease and Cushing syndrome, watch the video below. Keep in mind this video is presented from a nursing perspective, so some of the information is “nice to know” but not “necessary to know” for PTAs.

“Endocrine | Addisons vs Cushings NCLEX RN” by Simple Nursing is licensed under Fair Use

13.5 Thyroid Conditions

The function of the thyroid gland is to take iodine, found in many foods, and convert it into thyroid hormones: thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Thyroid cells are the only cells in the body which can absorb iodine. These cells combine iodine and the amino acid tyrosine to make T3 and T4. These hormones are responsible for controlling metabolism throughout the body.

13.5.1 Hyperthyroidism

The most common condition of increased thyroid function is Graves’ disease, which is an autoimmune condition in which the immune system directly attacks the thyroid gland. It predominantly affects women under the age of 40. Symptoms of Graves’ disease include hypermetabolic states: cardiac tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety and irritability, tremor, weight loss, frequent bowel movements and diarrhea, bulging eyes, fatigue, thick red skin, and sexual disorders, such as amenorrhea and reduced libido. An enlarged thyroid glad (goiter) may also be present.

Graves’ disease is treated with radioactive iodine therapy, anti-thyroid medications, beta blockers, and surgeries to remove all or part of the thyroid. Graves’ ophthalmopathy can be treated with steroids, eye surgery, and corrective lenses (prism glasses).

13.5.2 Thyroid Storm

In the case of an episode of extreme hyperthyroidism, the term “thyroid storm” is used. This is a life-threatening condition that is considered a medical emergency. A thyroid storm is often precipitated by a stressful event, such as illness, hospitalization, surgery, or emotional stress. The symptoms are hyperthermia (fever and hot, sweaty skin), tachycardia, hypertension, irritability and delirium. This state is followed by heart failure, and without medication, death. Anti-thyroid medications are administered as soon as thyroid storm is suspected. Up to 75% of people experiencing a thyroid storm will die.

13.5.3 Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is the opposite problem, where the thyroid is not functioning to an appropriate level. Autoimmune disorders, such as Hashimoto’s hyperthyroidism, are the most common cause of thryroiditis. Other causes include surgical removal of the thyroid, radiation treatment, some medications, and lack of iodine in the diet. If the pituitary gland is not functioning properly and not releasing thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), the function of the thyroid will also be depressed. The body’s metabolism is decreased in hypothyroidism, so symptoms include bradycardia, decreased blood pressure, weight gain, lethargy, depression, constipation, coldness, and dry skin. A goiter may be present in hypothyroidism, as the thyroid hypertrophies in an attempt to produce more T3 and T4.

Hypothyroidism is treated with hormone replacement therapy, usually for life. The hormones TSH, T3, and T4 can be replaced with synthetic hormones, and the patient can live a relatively symptom-free life.

13.5.4 Myxedema

If thyroid function is extremely low, a condition know as myxedema or myxedema coma can occur. Characteristics of a patient in this condition include: non-pitting edema, facial puffiness, thick tongue, slurred speech, hoarse voice, hypotension, bradycardia, hypoglycemia, hypothermia, cool, dry skin, decreasing mental abilities, and eventually, coma and death. Fortunately, this is a rare occurance in the US, where hypothyroidism is recognized and carefully managed in most cases. This condition is treated with synthetic T3 and T4.

For a video tutorial on hyper- and hypo-thyroid conditions, please watch the following video.

“Endocrine l Thyroid Hyperthyroidism vs. Hypothyroid NCLEX” by Simple Nursing is in the Public Domain

13.5 Pituitary Gland Disorders

The pituitary gland is often called the “master gland” because it secretes many different hormones that affect other endocrine glands. The pituitary gland can be dysfunctional due to congenital conditions, tumors (benign or metastatic), and reaction to some drugs. The hormones produced by the pituitary gland are listed below:

- Hormones (anterior lobe)

- Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH)

- Luteinizing hormone (LH)

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

- Thyroid stimulation hormone (TSH)

- Prolactin

- Endorphins

- Somatotropin (growth hormone) (GH)

- Hormones (posterior lobe)

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH)

- Oxytocin

If the pituitary gland is overactive, the condition is hyperpituitarism, and depending upon which area of the pituitary is affected any one or more of the hormones can be increased. If growth hormone (HGH or GH) production is increased during childhood, gigantism is the result, and the patient’s bones could grow to be very long, making the person unusually tall. If this hormone is produced in excessive amounts in an adult, acromegaly is the result. In acromegaly, the bones grow thicker, but not longer. TSH and other hormones can also be affected, leading to conditions of hyperfunction of the target organ for that hormone.

If the pituitary gland is underactive, the most common results are thyroid conditions ( decreased TSH), dwarfism (decreased GH), fatigue (decreased ACTH), and diabetes insipidus (decreased ADH).

Pituitary conditions are treated by tumor removal, if necessary, and often life-long hormone replacement therapy.

Endocrine System Resources

CDC site page for type 2 diabetes

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases