Chapter 8: Musculoskeletal Disorders

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to explain and discuss:

- Traumatic injuries to the bones, joints, extra-articular structures, and muscles.

- The effects of aging on the bones, joints, and muscles.

- Selected conditions affecting the bones, including the etiology, clinical presentation, progression, medical and physical therapy interventions, and prognosis of the disorders.

- Selected conditions affecting the joints, including the etiology, clinical presentation, progression, medical and physical therapy interventions, and prognosis of the disorders.

- Selected conditions affecting the muscles, including the etiology, clinical presentation, progression, medical and physical therapy interventions, and prognosis of the disorders.

- Medications commonly used to treat musculoskeletal conditions.

- The role of the physical therapist assistant in musculoskeletal conditions.

Chapter Contents

- 8.1 Trauma to the musculoskeletal system

- 8.2 Aging and the musculoskeletal system

- 8.3 Conditions affecting bones

- 8.4 Conditions affecting joints

- 8.5 Conditions affecting muscle

- 8.5.1 Myopathy

- 8.5.2 Inflammatory Myopathies

- 8.5.3 Inherited Muscular Myopathies: Muscular Dystrophy

- 8.5.4 Muscle conditions affecting other systems

- Fibromyalgia Syndrome

- Rhabdomyolysis

8.1 Trauma to the Musculoskeletal System

8.1.1 Bones

8.1.1.1 Fractures

Bone fractures are common injuries caused by many forms of trauma: falls, accidents, sports injuries, and intentional injuries can result in a complete, or incomplete, fracture of a bone. Fractures also occur due to weakness in bone, as in osteoporosis. These fractures are called “pathological fractures.” Common sites for pathological fractures include the vertebrae, hip (proximal femur), or tarsal and metatarsal bones of the foot. Wrist fractures are also a common result of falls on outstretched arms and hands, especially when the bone density is diminished.

8.1.1.1.1 Risk factors for Fracture

- Participation in activities that include high impact, collision, or fall risk

- Decreased bone density, as it osteopenia, osteoporosis, or Paget’s disease of the bone

- Balance and/or coordination deficit

- Cigarette smoking or other tobacco use

- Alcohol use

- Inadequate nutrition

8.1.1.1.2 Types of Fractures

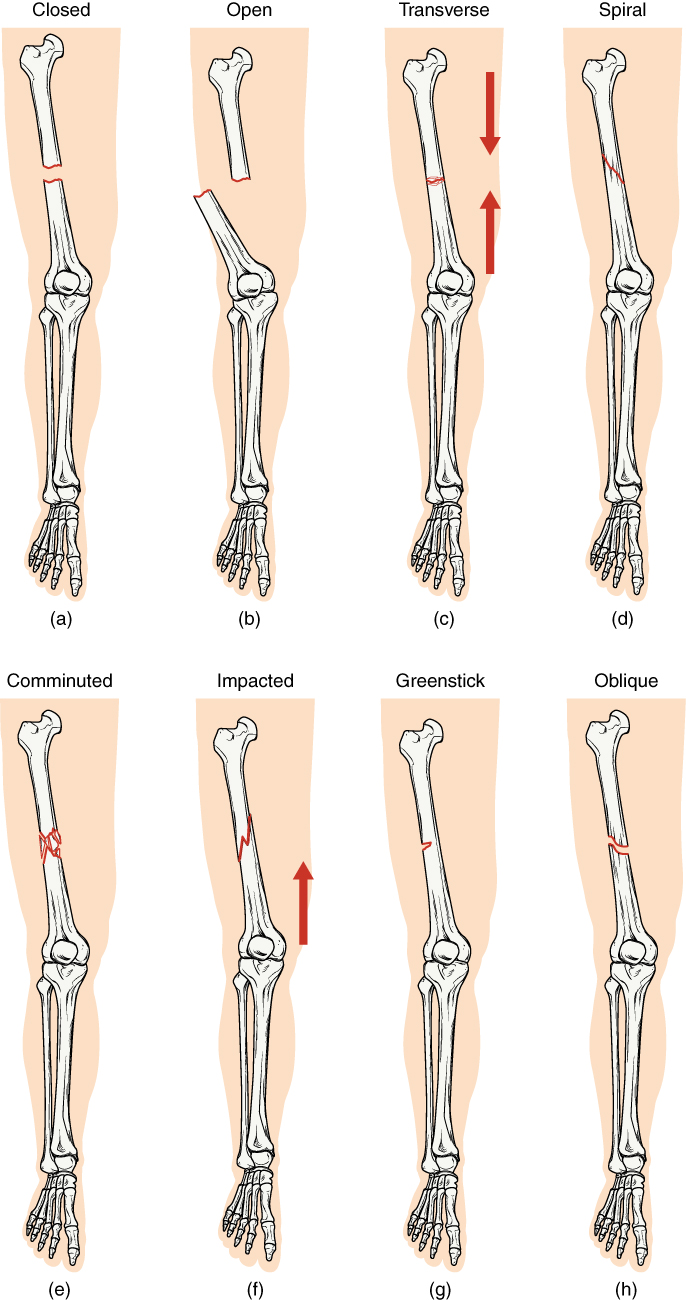

Bone fractures are categorized in several manners. Many are named specifically for the physician who first identified the particular fracture site and type (e.g. Colles’ fracture is a fracture of the distal radius with dorsal displacement of the wrist and hand). Often, the fracture is described by the site and type of fracture (e.g. transverse metaphyseal fracture of the right femur).

Two major categories of fracture are open and closed. A fracture is considered open if the skin is broken by the bone or if a wound exists that communicated with the bone or the hematoma caused by the fracture. An open fracture presents a higher risk for infection. An open fracture can also be called a compound fracture.

A spiral fracture often occurs when the bone was broken through a twisting mechanism. At least one part of the broken bone is twisted in a spiral fracture.

If there are several bone fragments, the term comminuted fracture is used.

The fracture is said to be impacted if the ends of the bone are crushed together.

A greenstick fracture can occur in children’s bones that are less brittle than adults’. The bone bends but does not actually crack or break.

An avulsion fracture occurs in an area of tendinous attachment. It causes a portion of bone to become detached due to a strong and sudden stretch of the tendon.

Nonunion fracture is a term applied to a condition in which a fracture has failed to heal after 9-12 months.

Stress fractures occur in bones that are under repeated stress, such as the tarsals, metatarsals, tibias, and vertebrae.

Special attention is paid to epiphyseal fractures in children. Since this is the area of growth in young bone, fractures in this area could stunt growth and lead to biomechanical asymmetries.

Another important distinction used in describing fractures is whether the bones are displaced or non-displaced. Displaced bones often need to be moved into alignment, a process often called reduction, before they are immobilized with a cast or other fixation device. The reduction process can be external, with or without anesthesia, or the fracture site might need to be aligned through surgery, which is known as an open reduction.

8.1.1.1.3 Healing and management of fractures

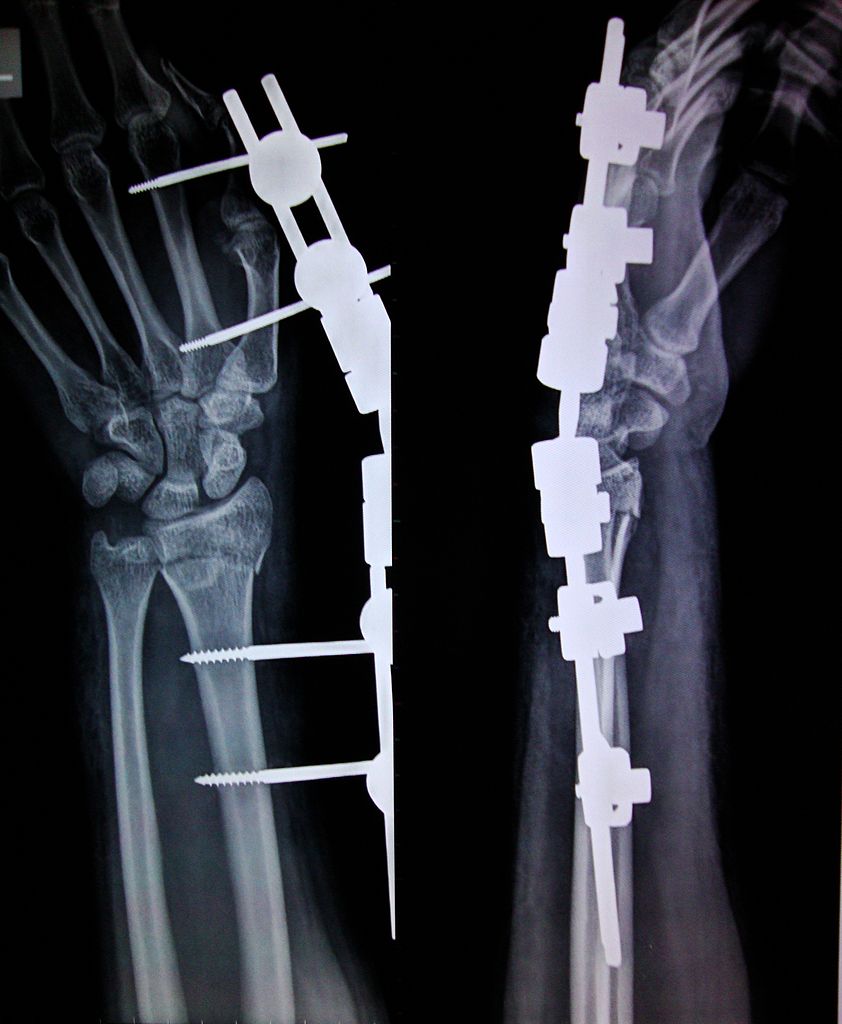

Immobilization of the bone segments is important for healing is often achieved by casting or splinting. Sometimes surgical implantation of screws, nails or plated, is necessary to achieve the bony alignment. This is called internal fixation. If “hardware” is surgically placed into the bone, but the metal supports are outside the body, the surgery is called external fixation.

Bone fracture healing

After a bone is broken, a hematoma forms between the ends of the bone fragments. New capillaries grow into the hematoma, and the increased blood supply brings macrophages to the area, which clean up dead tissue and other debris. Fibroblasts also increase in number and begin building a fibrocartilaginous callous in the proliferation stage of healing. This fibrocartilaginous callous unites the bony fragments and provides strong support for the area in a few weeks. The callous can be broken if subjected to substantial force. Some fibroblasts also lay down a bony matrix of collagen, which becomes bone through a mineralization process. A bony callous is in place in 6-8 weeks in normal bone healing in healthy adults. In children, the process is faster, and a bony callous can be in place in 3-4 weeks. The bony callous is reshaped and smoothed through osteoclastic activity in the remodeling stage. The remodeling should be complete in 18 months or less. Adult bone is generally considered strong enough to withstand normal forces 12 weeks after fracture.

Healing can be delayed, or in the case of non-union, many never completely occur. Factors that delay healing include:

- Tobacco use

- Alcohol use

- Some drugs

- Inadequate nutrition

- Presence of complications

- Infection

- Malunion

- Comorbidities, such as diabetes or osteoporosis

- Lack of weight-bearing or normal stresses on bone during healing process, as in the case of general immobilization (e.g. coma, head trauma, stroke, spinal cord injury)

8.1.1.1.4 Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a condition of decreased blood flow to an area that can occur following fracture. The condition is most common in the forearm and leg but can occur elsewhere in the body. Blood supply to an area can be compromised by a severe fracture, when blood vessels are torn and when edema is present. A cast adds to the pressure. Patients with compartment syndrome experience pain and paresthesia in the area. If allowed to continue, complete loss of sensation can occur, and the tissues, including the muscles and nerves, can become necrotic. Amputation may be the only option if this condition continues. In most cases, removal of the cast and elevation of the limb resolves the issue. Sometimes a surgical procedure called a fasciotomy might need to be performed to adequately reduce the pressure in the limb. Compartment syndrome is a serious condition. The PTA needs to ask every patient who has had a fracture about pain and sensation, and if compartment syndrome is suspected, needs to refer the patient to emergency medical attention right away.

8.1.1.1.5 Physical Therapy and Fractures

Physical therapy can play an important role in rehabilitation following bone fractures. In the early stages of fracture healing when inflammation is present, rest, ice, compression and elevation (RICE) are the most frequent interventions and recommendations. As the patient moves out of the acute inflammatory stage, common physical therapy interventions include range of motion, strengthening, gait training with and without assistive device, pain-reducing modalities, healing-inducing modalities, progressive exercise and functional training, proprioceptive training, and in some cases skin and wound care. Patient education is also an essential component of physical therapy, and patients recovering from fracture should be educated regarding risks factors for reinjury or delayed healing, appropriate exercise techniques and dosages, and progressive exercises and activities to promote successful return to previous activity level.

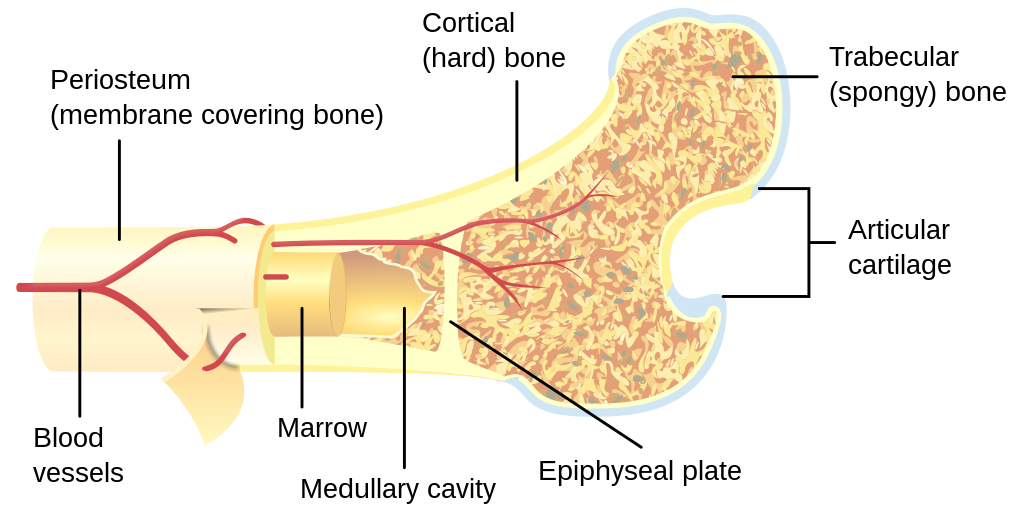

8.1.1.2 Bone Bruise

A bone is said to be bruised if it is damaged but the trabeculae within the bone remain intact. A collection of fluid and decomposing tissue can occur outside or inside the bone, just as it would in soft tissue under the outer layers of skin. A bone bruise can occur in response to traumatic injury or repetitive use. There are three types of bone bruise, depending upon location. A subperiosteal bone bruise occurs between the periosteum and bone. A subchondral bone bruise occurs between the cartilage and bone. An interosseous bone bruise occurs in the medullary canal of the bone. None of the types of bone bruise can be visualized through x-ray. MRI does detect bone bruises, but often the diagnosis is made by symptoms (pain, swelling, stiffness, color change of injured area, functional impairment) and lack of fracture noted on x-ray. Rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) are the recommended treatment for a bone bruise which could take 2-3 months to heal. Physical therapy is beneficial during and after healing to maintain or increase range of motion, strength, and endurance. An uncommon but serious complication of bone bruising is avascular necrosis of the bone and surrounding tissue.

Long “Description

Labelled items in the bone cross-section image.

- Periosteum (membrane covering bone)

- Cortical (hard) bone

- Trabecular (spongy) bone

- Articular cartilage

- Blood vessels

- Marrow

- Medullary cavity

- Epiphyseal plate

8.1.2 Joints

Sprains

A joint sprain is simply defined as an injury to a ligament. Sprains range from very mild (a stretch or minimal tearing of ligamentous tissue) to quite severe, involving complete or near complete severance of several ligaments. Joint sprains are common, especially in the ankle and wrist joints. Grades I, II, and III are used to describe the severity of sprain as follows:

- Grade I: mild pain and swelling, little no tear of the ligament

- Grade II: moderate pain and swelling, minimal instability of the joint, minimal to moderate tearing of the ligament, decreased range of motion

- Grade III: severe pain and swelling, substantial joint instability, total tear of the ligament, substantial decrease in range of motion; lack of stability may allow excessive joint motion, especially arthrokinematic motion

Swelling associated with sprains can either be due to effusion (swelling within the joint capsule) or effusion (swelling outside the joint capsule).

Sprains are diagnosed through physical examination and clinical presentation. X-rays do not show ligamentous damage but are often used to rule out fracture. Treatment for sprains includes RICE until acute inflammation has subsided. Patients might also benefit from protective splinting and bracing, and gait training with an assistive device for lower extremity injury. As healing continues, physical therapy interventions can progress to appropriate progressive exercise, proprioceptive retraining, muscular endurance training, and progressive return to activity. The length of time required to heal after a sprain is quite variable, depending upon the severity of the sprain, the previous level of activity of the patient, and general health and lifestyle of the patient. Mild sprains may heal in a few days or weeks. Severe sprains or those requiring surgical intervention may take many months for complete healing.

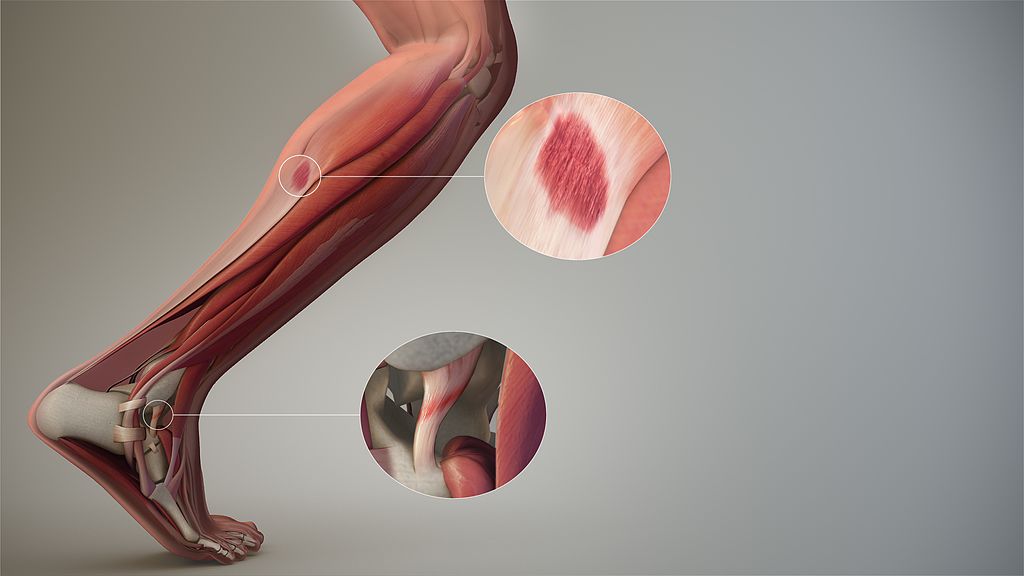

Picture shows sprain of anterior talofibular ligament and strain of lateral head of gastrocnemius at musculotendinous junction.

8.1.3 Muscles

8.1.3.1 Strains

Muscle or tendinous injuries, other than tendinitis and tendinosis, are called strains, tears, or pulls. Strains can occur in the muscle or tendon or at the musculotendinous junction where the muscle and the tendon meet. Strains can be acute or chronic conditions. Acute strains are usually the result of sudden trauma to the soft tissue, often a sudden and strong eccentric contraction. Chronic strains are the result of overuse of the muscle. According to the American College of Sports Medicine, strains are graded as follows:

- First degree (mildest) – little tissue tearing; mild tenderness; pain with full range of motion.

- Second degree – torn muscle or tendon tissues; painful, limited motion; possibly some swelling or depression at the spot of the injury.

- Third degree (most severe) – limited or no movement; pain will be severe at first, but may be painless after the initial injury

Strains can produce swelling and ecchymosis over large areas and can be painful or incapacitating. Areas most commonly affected by strains include the muscles of the low back, hip adductor muscles, hamstring muscles, and ankle muscles. The Achilles tendon is particularly vulnerable to severe sprains (rupture) during strong eccentric contractions of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles.

Strains are generally treated with the PRICE interventions in the acute stage. As the soft tissue heals, progressive range of motion, stretching, and strengthening activities are incorporated. In the case of second- or third-degree strains, surgical repair could be necessary. Healing could take several days to up to a year, depending upon the severity of the injury.

4 days after a pulled hamstring

8.1.3.2 Atrophy

Muscles that are not used are prone to atrophy, or decrease in size. Inactivity for any reason causes muscles to atrophy. Nerve injuries, muscle injuries, bone injuries, casts, and splints can cause immobility leading to muscular atrophy. Patients recovering from surgery or serious illness may be sedentary or immobilized, which can also cause atrophy. Any muscle that is not used regularly will become smaller and weaker over time. Patients who are taking glucocorticoid medications for extended periods are also subject to atrophy as these chemicals increase the rate of breakdown of muscle tissue proteins.

Physical therapy can help to minimize muscular atrophy by incorporating exercises and activities early in recovery. Exercise should be progressed gradually according to accepted protocols for the patient’s diagnosis, the patient’s goals, and the patient’s general health and fitness level. It is important for a PTA to recognize that muscles tissue that has not been used becomes stiffer and weaker and is therefore more easily damaged than healthy muscle tissue. Caution is necessary when performing stretching and strengthening activities with muscles that have atrophied.

8.1.4 Articular and Extra-Articular Structures

Tendinopathy: Tendinitis and Tendinosis

Tendinitis involves the acute inflammation of a tendon. Swelling, warmth, redness and pain with movement occurs. Tendinitis usually occurs in response to a sudden forceful contraction of the muscle or sudden stretch of the muscle and tendon. Areas of the body where tendons are frequently stretched or used and areas where tendons are impinged or irritated by rubbing against other structures are the most likely to be involved. Tendons that are inflamed, especially for a long time, are more likely to rupture. Common areas for tendinitis include tendons of the biceps brachii, supraspinatus, patellar tendon, Achilles tendon, and the common extensor and common flexor tendons of the forearm.

Tendinosis is a common injury to tendons, which is associated with chronic overuse, rather than with microtrauma from sudden stretch or forceful contraction. The tendon damage, which appears as microscopic degeneration and disorganization of the fibers of the tendon, usually occurs in response to overuse, misuse, or joint misalignments. Cracking or grating sounds can sometimes be felt or heard with joint movement. Palpation will often reveal areas of tenderness, and lumps and bumps which can be felt on the tendon. Tendinosis also commonly occurs in the biceps brachii, supraspinatus, patellar tendon, Achilles tendon, and the common extensor and common flexor tendons of the forearm.

Physical therapy interventions for tendinitis generally include RICE in the early stages to help decease inflammation. Once the inflammation has subsided, gradual exercises for ROM, stretching, and strengthening can be incorporated. It is important for the PT or PTA to correct postural or joint misalignments during activity in order to prevent recurrence of the tendinitis. Tendinosis can also involve some inflammation, so RICE interventions can be useful at times. Tendionosis is long-standing injury, and may take many months to completely heal. Tendinitis generally heals within a few weeks.

Medical interventions for tendinitis include NSAIDs and steroidal medications (oral or injected), For tendinosis, NSAIDs can be helpful when inflammation is present, but should not be used for long periods of time. Sometimes surgical releases or tendon transfers are necessary in tendinosis.

Physical therapy can be very useful for either tendionsis or tendinitis. As stated above, RICE interventions are most often included in tendinosis treatment, and can be used initially when the condition is tendinitis. For both types of tendinopathy, physical therapy can be beneficial to the patient to help with stretching short or stiff structures and strengthening supporting structures. Improving posture and patterns of movement to avoid future injuries should also be included in physical therapy for either tendinitis or tendinosis.

Watch the video below for some good information about physical therapy and tendon injury.

8.1 – Resource-13 – FXNL Media – Tendinitis, Tendinosis, Tendinopathy?

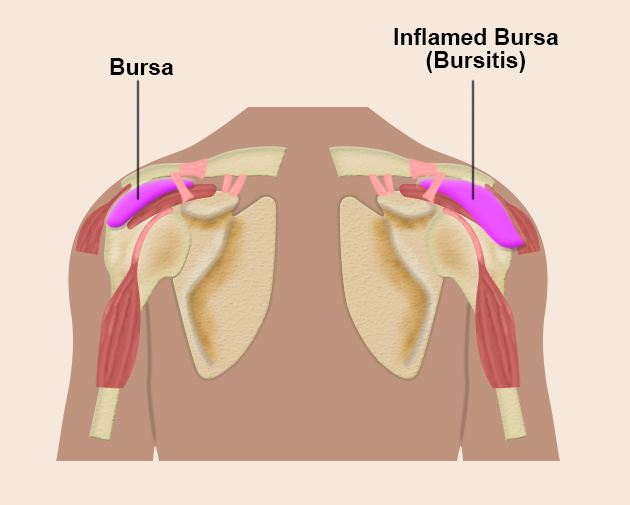

8.1.4.2 Bursitis

Bursitis is inflammation of the bursae in a joint. Bursae are common joint structures which help decrease friction between bony surfaces and between tendons and bones. Bursae that are compressed or irritated often are the most likely to become inflamed. The signs and symptoms include pain that is aggravated by movement, as the bursae can get “pinched” during motion. Tenderness, redness, and swelling are common signs, along with pain.

Physical therapy interventions are similar to those for tendinitis. RICE during periods of acute inflammation is the rule. Once the inflammation is decreased, gradual return to function with attention to posture and movement patterns is essential. Medical interventions include NSAIDs, steroids (oral, injected), and occasionally surgery.

The most common areas for bursitis are the shoulder, elbow, hip, knee, and ankle.

8.2 Aging and the Musculoskeletal System

8.2.1 Bones

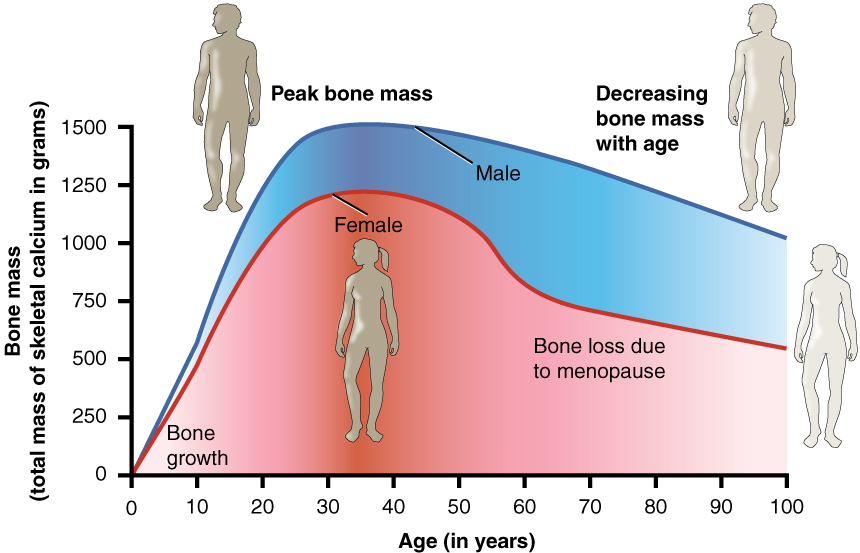

Bones are quite strong and able to absorb and transmit large forces throughout the human body. As people age, however, bone density decreases. Bone density begins decreasing around the age of 30 and continues to decrease every year thereafter. Although bone density decreases are found in both men and women, the biggest decreases in bone density occur in women when estrogen levels decrease after menopause. Bone density can decrease by 10% each year in postmenopausal women. For this reason, bone fractures (pathological and traumatic) are seen with much greater frequency in older adults than in younger people. The bones most likely to sustain fracture include the vertebrae, the hip (femoral neck), and the distal radius and ulna. Lack of density in the vertebral bodies can cause flattening and fracture which often lead to decreased overall height and kyphotic posturing. The effects of aging on bone density can be slowed by participation in weight-bearing exercise and maintaining a diet that contains adequate calcium and Vitamin D.

Long Description

A graph of Age versus bone mass, where the x axis is age and goes from 1 to 100 years, and the y axis is bone mass and goes from 0 to 1500 grams of calcium in the skeleton. Two curves (one for males, one for females) start at 0, 0 and peak around age 35 – 40. The female peak is around 1250 grams; the male peak is about 1500 grams. They then decline until age 100 where men are about 1100 grams and women are about 750 grams.

8.2.2 Joints

Decreased bone density along with misuse or overuse of joints and muscle weakness or imbalance can lead to changes in joint mechanics and structure. These changes are common in the aging adult, producing pain and stiffness associated with osteoarthritis. Ligaments which support the joint can become weak, stretched, stiff, or otherwise damaged with age. Ligamentous changes are associated with biomechanical changes in the joint motion, pain, and muscular weakness. Joint protection might be a necessary aspect of physical therapy care for older adults who have pain or weakness due to arthritic changes. Adaptive devices for ambulation and orthotic supports might be useful to help maintain function and decrease pain.

8.2.3 Muscles

Sarcopenia is a condition in which muscle tissue is lost. As people age, some sarcopenia is to be expected. It is estimated that 1 in 20 community dwelling older adults and 1 in 3 adults living in long-term care facilities has significant sarcopenia. The risk of falls increases in the presence of sarcopenia, as does the risk of increased morbidity and mortality associated with falls and other conditions and illnesses. Resistance exercise is effective in improving muscle strength and function, although increases in muscle mass are not observed. (Age Ageing. 2014 Nov; 43(6): 748–759.

Published online 2014 Sep 21. doi:

- Oxford Academic – Age and Ageing

- National Library of Medicine

- Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, Zúñiga C, Arai H, Boirie Y, Chen LK, Fielding RA, Martin FC, Michel JP, Sieber C, Stout JR, Studenski SA, Vellas B, Woo J, Zamboni M, Cederholm T.

Age Ageing. 2014 Nov;43(6):748-59. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu115. Epub 2014 Sep 21. Review.

Type II muscle fibers (fast-twitch) seem to be particularly susceptible to sarcopenia are seen at proportionately lower levels than Type I muscle fibers (slow-twitch) in older individuals. PTAs should know that muscle strengthening is possible at any age and appropriate resistance exercise can help decrease the decline of muscle strength in aging adults.

8.3 Conditions Affecting Bones

8.3.1 Osteoporosis and Osteopenia

Osteopenia and osteoporosis refer to the loss of bone mass density (BMD). Bone density decreases with age, but some individuals lose bone at a faster rate than others. Risk factors for osteopenia and osteoporosis include cigarette smoking, lack of weight-bearing exercise, being underweight, decreased levels of estrogen (post-menopausal, surgical removal of ovaries), alcoholism, kidney disease, hyperthyroidism, positive family history, and Caucasian or Asian ethnicities. Some medications, such as corticosteroids, anti-seizure medications, some anticoagulants, and chemotherapy drugs are linked to the development of osteopenia and osteoporosis.

Osteopenia and osteoporosis are diagnosed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA scan). If a person’s BMD T-score is between 1.0 and 2.5 standard deviations below the mean for the age and sex of the person being scanned, the diagnosis is osteopenia. If the BMD T-score falls below -2.5, the diagnosis is osteoporosis. Not every person who develops osteopenia will progress to osteoporosis, but a significant number of individuals do.

The pathophysiology of these disorders is that bone is broken down through osteoclastic activity at a faster rate than it is produced through osteoblastic activity. This leaves the cancellous bone with large air spaces within the bony matrix and bone that is very porous and easily damaged.

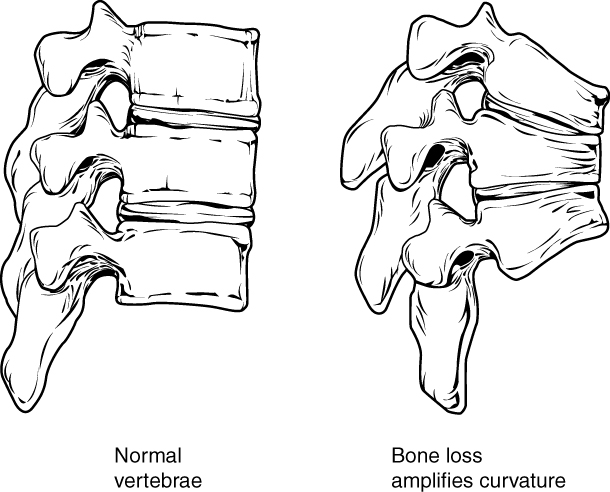

These disorders are silent, as they are symptom-free until osteoporosis is quite advanced. Fractures are the major concern with decreased BMD. Bones can be broken with little stress and healing can be difficult. The vertebral bodies, proximal femur, and distal forearm bones are the most common fracture sites in osteoporosis. Vertebral fractures often occur in result to continual pressure on the vertebral bodies in standing and sitting. The anterior portion of the vertebral bodies becomes crushed, and the spine takes on a kyphotic posture. Kyphosis can affect lung and heart functions and make ambulation and other exercise difficult.

Several medications are available for the treatment of osteoporosis and osteopenia, including bisphosphonates, which are most useful in preventing future fractures in a person who has already suffered one fracture from decreased BMD. Teriparatide (a recombinant parathyroid hormone) is sometimes used in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. There is less evidence of benefit for medications in people diagnosed with osteopenia than there is for those diagnosed with osteoporosis.

You can test your knowledge of bone density and osteoporosis through a Khan Academy quiz at:

8.3.2 Osteomalacia

Osteomalacia is a softening of the bones due to inadequate mineralization of bone. Whereas osteoporosis is caused by decreased density of bone secondary to loss of the bony matrix, osteomalacia is a demineralization of bone. It is linked to impaired mineralization of bone primarily due to inadequate levels of phosphate, calcium, and vitamin D, or because of increased resorption of calcium. Problems with absorption of calcium and other nutrients in the large intestine or problems with renal insufficiency can cause osetomalacia.

Osteomalacia is a generalized bone condition in which there is inadequate mineralization of the bone. Many of the effects of the disease overlap with the more osteoporosis, which is much more common, but the two diseases are significantly different. The symptoms of osteomalacia include:

- Diffuse joint and bone pain (especially of spine, pelvis, and legs)

- Muscle weakness

- Difficulty walking, often with waddling gait

- Hypocalcemia

- Compressed vertebrae diminished stature

- Pelvic flattening

- Weak, soft bones

- Easy fracturing

- Bending of bones

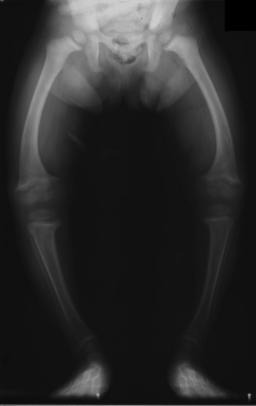

In children, a lack of calcium or Vit D causes a condition called Rickets, which is very similar to osteomalacia in adults.

Rickets and osteomalacia can be prevented or treated through exposure to sunlight, and/or dietary supplementation with Vit D, calcium, or phosphorus.

8.2.3 Paget’s Disease of Bone

Paget’s disease of bone, or Paget’s disease, is a disorder that causes bone to breakdown and rebuild and remodel, but in a very disorganized manner. This leads to thickened and weakened bones. Bone pain, pain with movement, and fracture are symptoms associated with Paget’s disease. The condition can affect one or more bones, most often the pelvis, spine, skull, and femur. If the skull is affected, hearing loss and headaches can occur.

Paget’s disease is genetic, but genetic patterns are less predictable than seen in most inherited conditions. There may be viral Paget’s disease affects men more often than women and is most common in people of European dissent. The overall incidence seems to be decreasing.

Most patients are diagnosed incidentally. That is, they are not experiencing signs or symptoms of Paget’s, but are being evaluated for another condition when bone deformities are noticed by a health care provider. Many patients remain asymptomatic for many years. Complications may develop with Paget’s disease, including osteoarthritis, heart failure, kidney stones, and nervous system involvement. Rarely, Paget’s progresses to bone cancer.

Paget’s disease has no known cure, but it can be managed. Treatment for Paget’s disease includes medications that are also used for osteoporosis: bisphosphonates are the most commonly prescribed. Physical therapy may be beneficial to reduce pain and improve movement patters and posture. Exercise is important for maintaining joint mobility, preventing weight gain, and maintaining cardiovascular fitness in patients with Paget’s disease. Because the bones may be weak and easily fractured, care must be taken to keep stress to a minimum on fragile bones. Assistive devices, orthotics, and splints can be useful for patients with Paget’s disease.

8.3.4 Osteochondrosis

Osteochondrosis is a group of orthopedic conditions that occur in children and adolescents. The growing bone, specifically the epiphyses are affected, as they undergo a period of avascular necrosis and then go through the process of rebuilding and remodeling. The cause of the condition is unknown, but heredity and anatomical configuration seem to be involved in the development of osteochondrosis. Rapid growth, trauma, overuse, and dietary imbalances have also been suggested as possible inciting factors. Pain is the major symptom of all types of osteochondrosis. Some types also cause significant swelling. Osteochondrosis is a self-limiting condition, but changes in bone structure can remain throughout life. The treatments and prognoses vary with the different types of disorder.

Three groups of osteochondritis exist: spinal, articular, and non-articular. Specific named conditions that fall under the osetochondritis umbrella are listed below.

8.3.4.1 Scheuermann’s disease

Spinal: Scheuermann’s disease: This disorder causes back pain and kyphosis of the thoracic spine in preadolescents and adolescents. The vertebral bodies compress anteriorly, in a process termed “anterior wedging.” The kyphosis of the thoracic spine is often accompanied by rounded shoulders, forward head, and increased lumbar lordosis as compensatory mechanisms. Barrel chests and large lung forced vital capacities are common compensations, as well. Patients with Scheuermann’s disease can experience pain in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, and they are structurally unable to maintain normal spinal alignment.

The etiology of Scheuermann’s disease is unknown. Several genes have been studied in relation to the disorder, but none has proven to be responsible for the condition. It is postulated that the cause is probably multifactorial.

Scheuermann’s disease is most often treated with a conservative approach involving physical therapy. The PT intervention generally includes postural education and ROM to the spine and strengthening to the spinal and abdominal muscles. General exercise instruction and cardiovascular conditioning are also important in helping patients manage their condition. Medications to control pain are sometimes used. In severe cases, surgical intervention to stabilize (fuse) the spine or prevent further deformity might be necessary. These surgeries are quite invasive and only used as a last resort.

8.3.4.2 Legg-Calve-Perthes disease

Articular: Legg-Calve-Perthes (LCP)

LCP affects the blood flow to the femoral head, causing necrosis and degeneration. The femoral head eventually revascularizes and remodels in the acetabulum, but this process takes several years. The disorder most commonly affects children ages 4 to 8 but can affect children as young as 2 or as old as 15. The etiology is unknown, and probably multifactorial.

Signs and symptoms of LCP include uneven gait (limping) and groin and hip pain.

The treatment for LCP is usually conservative, using bracing to maintain the legs in an abducted position while the femoral head is revascularizing and reforming. Nighttime traction is sometimes used to separate joint surfaces and relieve pressure on the hip joint. Physical therapy is usually included in the treatment. PT interventions include stretching of tight hip musculature, strengthening of supporting musculature and monitoring the condition for progress or regression. Children with LCP enjoy activity and will try to remain active throughout the healing process. Aquatic therapy can be particularly beneficial because of the decreased weight-bearing in the water.

The concern in LCP is that the head of the femur with not remodel in the most optimal shape, leading to osteoarthritis and poor hip biomechanics in the future. Coxa plana (flattening of the femoral head) is not uncommon in the aftermath of LCP. Hip arthroplasties are common in adults who had LCP as children.

8.3.4.3 Sever’s disease

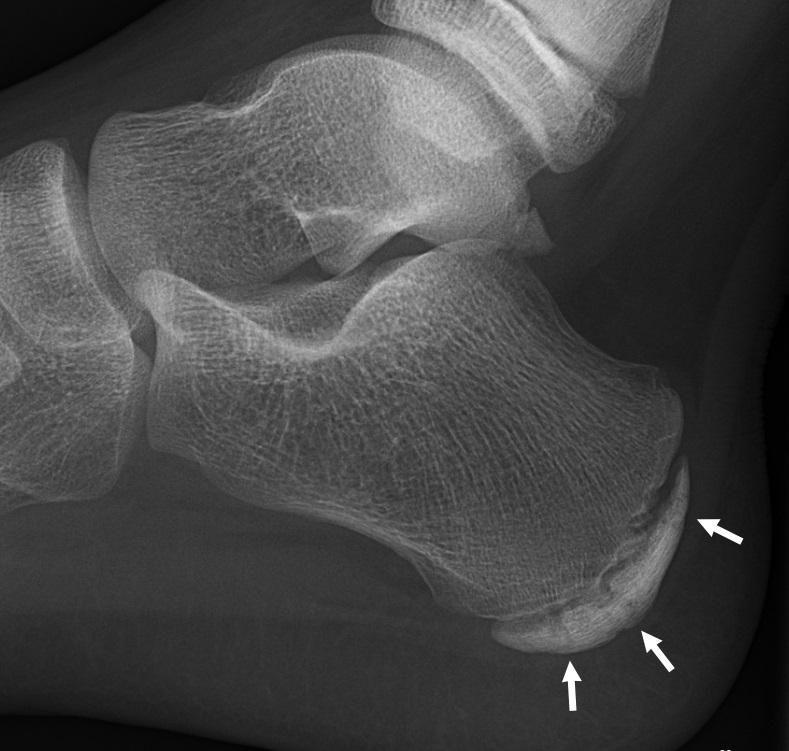

Non-articular: Sever’s disease

Sever’s disease affects the calcaneus (calcaneal apophysitis) and is associated with overuse. This disorder occurs in children, involving the growth plate in the calcaneus. It is more common in children who “over-pronate” when walking and running and in those who participate in activities involving running and jumping. The etiology is purely overuse.

The signs include a painful heel (posterior and plantar surface) that is aggravated by activity and a positive “squeeze test” (pain when squeezing the calcaneus). Conservative treatments, including RICE, avoiding activities or footwear that irritate the heel area, stretching the plantar fascia and gastrocnemius, soleus, and hamstring muscles, and gradual strengthening of supporting musculature and returning to activity. Icing several times per day is often recommended. Custom-made orthotics might be useful in maintaining proper foot and ankle alignment.

Sever’s disease is self-limiting, that is it will get better over time. Physical therapy can be useful in educating the patient regarding appropriate stretches and activities. Over-the-counter NSAIDs are usually sufficient for decreasing pain and swelling associated with Sever’s disease.

8.3.4.4 Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Non-articular: Osgood-Schlatter’s Disease

Osgood-Schlatter’s disease (aka apophysitis of tibial tuberosity) is a common inflammation of the tibial tuberosity in response to overuse of the quadriceps and patellar tendon. It occurs most often in children and adolescents who participate in sports that involve running and jumping.

The cause of the injury is entirely overuse in a skeletally immature person. Signs and symptoms include tenderness and swelling over the tibial tuberosity where the patellar tendon inserts into the tibia. A prominent “bump” on the tibial tuberosity is often observed.

The treatment for Osgood-Schlatter’s disease is to avoid aggravating activities, incorporate RICE activities, and stretch and strengthen the quadriceps and hamstrings. Ice is an important modality to incorporate after activity. NSAIDs are sometimes useful if the pain and swelling are remarkable. Physical therapy can be very helpful in educating the patient about safe return-to-activity planning, appropriate stretches and exercises, and the use of RICE. The condition is self-limiting, although the bump on the tibial tuberosity may remain throughout life. Rarely, the pull of the patellar tendon on the tibial tuberosity is so great that an avulsion occurs. Surgery could be recommended in severe cases.

8.3.5 Osteomyelitis

An infection of bone is called osteomyelitis. Bone is most often infected by bacteria, and less commonly, fungi. The most common type of infection is staph aureus, which infects the bone through the blood supply or because of infection in adjacent areas. Children are affected by osteomyelitis more often than adults because of the abundant blood supply to the growing bones. The long bones of the extremities are the most common sites for infection in children. If adults get osteomyelitis, it is most often associated with a penetrating wound or an adjacent infection, such as cellulitis. Infections occurring during surgery, such as joint arthroplasty or bony fixation can also be the source of infection. In adults, the pelvis and vertebrae are the most common sites for infection. The immunocompromised are most susceptible to bone infections. This would include the very old and very young, people with diabetes or other immunosuppressive condition, and IV drug users. Osteomyelitis can be a secondary complication to tuberculosis, in which case it most often affects the vertebral bodies of the spine.

The symptoms of osteomyelitis include pain, redness, swelling, weakness, and fever. In children with lower extremity involvement, decreased weight-bearing can be the first sign of osteomyelitis.

Osteomyelitis can be cured with high doses of antimicrobial medications. The earlier the intervention the more likely the complete recovery of the patient. If a patient has poor blood supply to the area of infection, amputation is sometimes the necessary intervention.

8.3.6 Osteogenesis imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a genetic disorder that causes weakness in bones. It is often referred to as “brittle bone disease” because of poor bone density and likeliness of fracture. Osteogenesis imperfecta is a dominant trait, passed from parent to child, or it can occur as a spontaneous mutation. There are at least 8 types of osteogenesis imperfecta, with Type I being least severe, and Type II being most severe.

The underlying problem with osteogenesis imperfecta is a disorder of the connective tissue, where type 1 collagen is deficient. The signs and symptoms include frequent fractures, blue sclera of the eyes, short height, hypermobility of joints, hearing loss, breathing problems, and tooth loss and decay.

There is no cure for this condition. Treatment for osteogenesis imperfecta includes lifestyle modifications to avoid stress and injury to bones, assistive devices to help with mobility, orthotics to protect vulnerable bones and joints, and surgery to prevent or repair conditions caused by the disease. Physical therapy can play a major role in injury prevention and in rehabilitation following fracture or surgery. Smoking and tobacco use in general should be avoided to help maintain bone strength. Medications to decrease pain are often prescribed for osteogenesis imperfecta. Bisphosphonates are also often prescribed, although their effectiveness is questionable.

8.4 Conditions Affecting Joints

For general information and categorization of different types of arthritis, watch the following video.

8.4 – Resource 01 – Khan Academy – What is arthritis?

8.4.1 Osteoarthritis (OA)

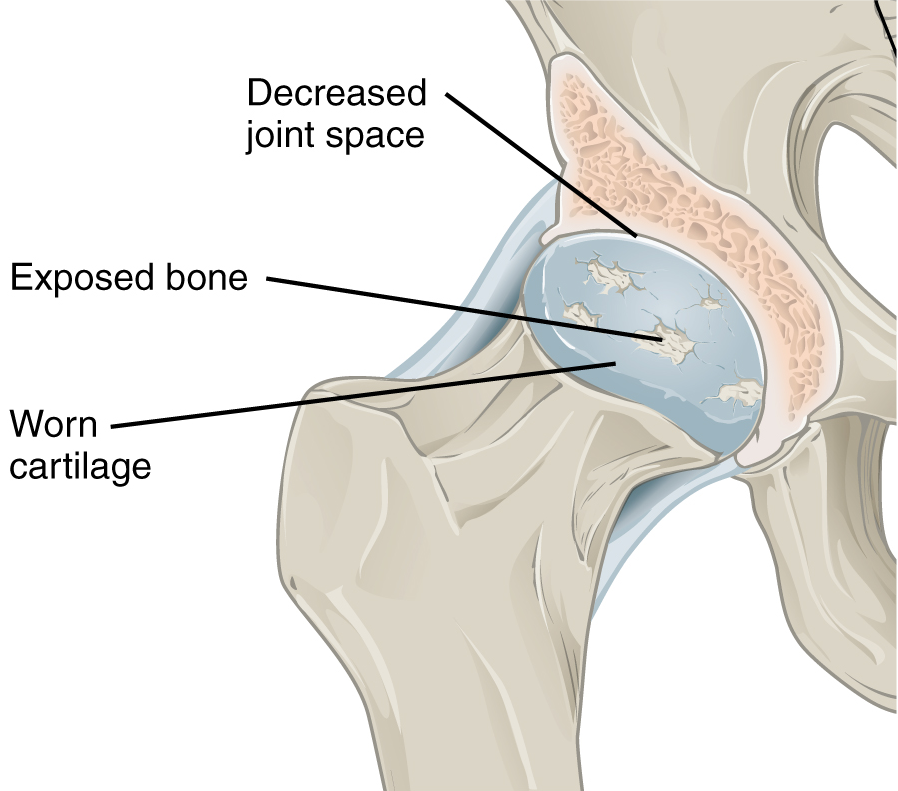

Osteoarthritis (OA), also known as degenerative joint disease (DJD), is a common disorder that causes destruction of the articular cartilage and underlying bones. It is associated with joint use or overuse, primarily in the case of joint malalignment, previous injury, or muscular weakness. Other factors that have been identified as risk factors for OA include advancing age, being overweight, and having a positive family history for OA. The hip, knees, spine, and hands are the joints most common affected by OA. The disorder does not appear in symmetrical patterns and may affect only one or 2 joints in the body.

People with OA experience pain, stiffness, and swelling in joints. The pain is aggravated by use and relieved by rest. Stiffness is made worse by immobility and is generally worse in the morning or after long periods of sitting. The morning stiffness associated with OA is usually less than that associated with RA. Activity helps alleviate stiffness, but overactivity can increase pain. Over time, pain in the affected joints become more painful, range of motion decreases, and daily activities can be adversely affected. Crepitus (cracking noises) during joint motion is associated with OA. In the fingers, Bouchard’s nodes and Heberden’s nodes are frequent signs. Bouchard’s nodes are bony over growths on the PIP joints, while Heberden’s nodes appear on the DIP joints.

The formation of hard knobs at the middle finger joints (known as Bouchard’s nodes) and at the farthest finger joints (known as Heberden’s nodes) are a common feature of osteoarthritis in the

Osteoarthritis in the knee. Note the narrowed joint space, osteophyte formation and increased bone density in the lateral tibial condyle.

Many changes in the joint can be noted in the presence of OA. The synovium and joint capsule can become inflamed, weakened, and the supporting ligaments can become thickened and fibrotic. Osteophytes, or bone spurs, can form on the edges of the bone. The subchondral bone volume increases, while bone mineralization decreases.

Gentle activity and joint motion are recommended in the prevention and treatment of OA. The condition can worsen over time, and braces, supports, splints, or orthotics can be considered to offer support and protection to painful joints. Ambulation assistance could be necessary, so canes, crutches, and walkers can be considered. Surgical joint replacement is an option, particularly in the hips, knees, and shoulders. For severe OA with stenosis in the cervical or lumbar spine, laminectomies or other decompressive surgeries or fusions are available.

Physical therapy is very helpful in the management of OA. Supportive joint protection, ambulation assistance and gait training, postural training, and specific exercise with special attention to joint mechanics are common physical therapy interventions for people with OA. Thermal modalities may also be helpful in relief of inflammation and pain associated with OA. Aquatic therapy is also often employed to decrease stress on joints during exercise.

Medications for OA are usually NSAIDs, injected steroids and other pain-relieving drugs. Opioids can be used, but because of their addictive qualities, they should be used with caution.

8.4.2 Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a condition that causes joint stiffness, pain, and impaired function, but it is quite different than OA. RA is an autoimmune disorder that affects the synovium of the joints. The synovium becomes quite inflamed and produces pannus, a type of granulation tissue that is formed in response to inflammation. The granulation tissue causes contraction of the joint capsule and alters the shape of the joint. RA usually appears in a symmetrical pattern, that is it affects the same joints on the right and left sides of the body at the same time. It is systemic, so it can affect any joint in the body, but is most likely to affect the joints of the hands or feet first. The DIP joints of the fingers are generally spared in RA, so Bouchard’s nodes may be present, but not Heberden’s nodes. Over time, joint motion becomes painful, then impossible, joint deformities ensue, and the joints fuse, or ankylose.

Because RA is inflammatory, joints can be warm and red during an exacerbation, or flare. Because it is systemic, fever and malaise might also accompany flares. Sometimes, other areas of the body are involved, and conditions associated with RA include cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, interstitial lung disease, fatigue, and depression. Joints affected by RA are stiffer in the morning and respond positively to moderate exercise. It is important for people with RA to maintain adequate muscle strength around the joints to help support the joints and preserve normal joint motion.

Deformities of the hands are particularly noticeable in RA. Swan neck deformities and boutonniere deformities are common. Ulnar drift is noted in the fingers and metacarpals. The carpals can fuse. Similar issues can be found in the feet, resulting in hammer toes, claw toes, and bunions.

X-ray of the wrist of a woman with rheumatoid arthritis, showing unaffected carpal bones in the left image, and ankylosing fusion of the carpal bones 8 years later in the right image.

Physical therapy can be very helpful for patients with RA. Energy conservation techniques can be employed to help a patient manage symptoms and prevent flares from overuse. Modalities for pain (cold during flares, heat or cold in other times), postural exercises, muscle strengthening, cardiovascular conditioning, joint range of motion exercises, joint protection through splinting or bracing, and ambulation aids when needed are important aspects of physical therapy intervention. Patients with RA often respond positively to aquatic exercise, which decreases joint stress associated with weight-bearing.

Medications for RA include glucocorticoid (steroidal) drugs, NSAIDs, biologic response modifying drugs, and disease modifying drugs. Some common ones include hydroxycholoroquine sulfate (Plaquenil) and methotrexate (disease modifying), etanercept (Enbril) and adalimumab (Humira) (biologic), prednisone (steroid), and Celebrex, Motrin, Advil, or Voltaren (NSAIDs). Because the biologic response and glucocorticoid medications cause immunosuppression, patients who are taking these medications are susceptible to communicable diseases, and they should get flu and pneumonia vaccines. They also need frequent liver function testing to check on the liver’s ability to function as it process some of these strong medications.

See the video below for a good summary contrasting OA and RA.

8.4 – Resource 09 – Khan Academy – Osteo vs. rheumatoid: symptoms

8.4 – Resource 10 – Khan Academy – Osteo vs. rheumatoid: pathophysiology

8.4.3 Degenerative Disc Disease (DDD) (aka: Degenerative Intervetebral Disc Disease)

Degenerative Disc Disease (DDD) is a disorder of the intervertebral discs of the spinal column. It is not a disease, rather it is a condition, and it is not particularly degenerative, so the name is sometimes alarming and confusing for patients. It is similar to osteoarthritis, and indeed, osteophyte formation and other bony changes found in OA can also be present in DDD. But because it occurs in the intervertebral joints and involves the discs, rather than synovial joints, it is a separate condition. In DDD, fibrotic changes and herniations occur in the discs of the spine. This decreases the joint space between vertebrae and causes narrowing of the intervertebral foramen. This narrowing can irritate nerve roots, pain is often present centrally, over the area of involvement or pain can radiate along peripheral nerves. Sensory disturbances, such as numbness and tingling in the dermatome are also common. The facet joints (zygopophyseal joints) can become misaligned because of changes in the disc, causing further pain and dysfunction.

Physical therapy can help patients with DDD by correcting postural faults, improving range of motion, and strengthening supporting musculature. Habitual patterns of movement can also be addressed and improved. Pain and the use of modalities may also be useful in physical therapy sessions. Other options for medical treatment include steroidal injections and surgeries to remove or replace the disc, and fusions of adjacent vertebral bodies.

8.4.4 Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS)

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory arthritic condition, affecting the spine. Genetics are involved in the development of AS, but there seems to be an environmental trigger, as almost all people with AS have a common genetic marker HLA B-27), but not many people with the genetic marker have AS. Males are more often affected by AS than are females, and it generally becomes apparent in late adolescence or early adulthood.

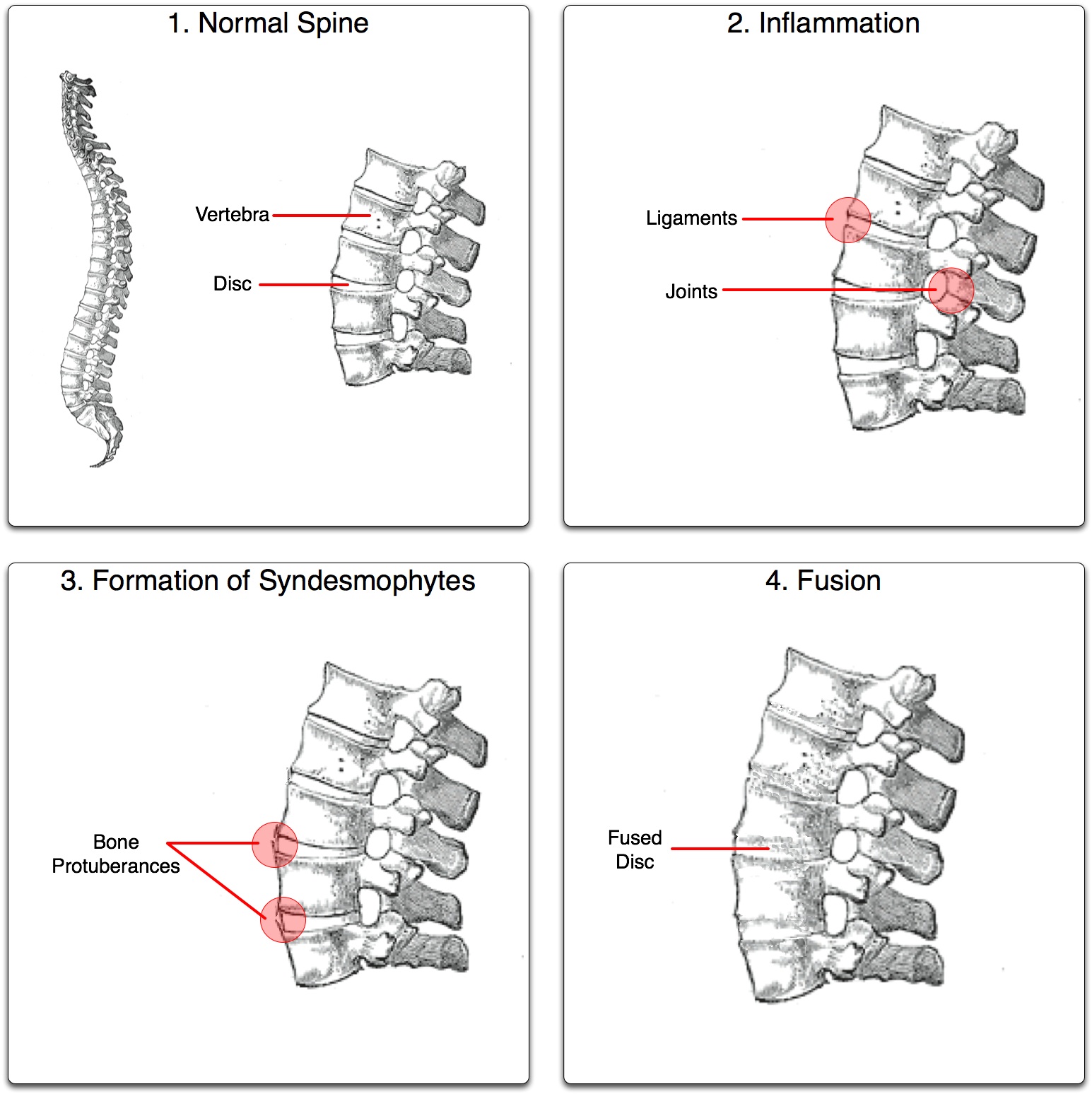

The pathophysiology of AS includes arthritic changes in the spine, starting in the sacral and lumbar areas, and progressing upward to involve the thoracic and cervical spines. The disorder begins with pain and stiffness, and over time, the vertebral bodies become fused, or ankylosed, with bony tissue. AS is sometimes called “bamboo spine” because of the bamboo-like appearance of the spine on x-rays. In the auto-fusion process the thoracic spine often fuses in a kyphotic posture, which can lead to pulmonary and cardiac dysfunction. Because AS is systemic, broad symptoms, such as fever and malaise may accompany the disease, and other areas of the body can be involved. Inflammation of the eye, aorta, and aortic valve are present in some individuals with AS. Other problems can include fibrosis of the lungs and inflammation of the prostate in men.

Physical therapy is beneficial for patients with AS. Pain relief through exercise and modalities is often used. The pool is a good place for exercise because the buoyancy of the water creates a comfortable environment for motion. Particular attention should be paid to the spinal posture of patients with AS, as kyphosis is common, and emphasis on posture and strengthening of spinal extensor muscles may help the spine to fuse in a more erect position.

Medications used to manage the symptoms of AS include anti-inflammatories NSAIDs such as (buprofen, COX-2 inhibitors, indomethacin, and naproxen. Disease modifying drugs, such as sulfasalazine are also used. Opioid pain killers are used on occasion for AS, but their use should be limited because of the addictive nature of the drugs.

8.4.5 Infectious Arthritis

Most infectious arthritis cases are due to staphylococcal infections or gonorrhea infections. The problem is an active infection locally in a joint, rather than an autoimmune disorder like reactive arthritis. The joint most often infected is the knee, and the knee appears red and swollen and is quite painful. The most important reason to treat this disorder with antibiotics is that is can progress to septic arthritis and affect the whole body.

8.4 – Resource 13 – Khan Academy – Infectious Arthritis

8.4.6 Reactive Arthritis (Reiter’s Syndrome)

In reactive arthritis, or Reiter’s Syndrome, the immune system attacks its own body cells as a latent reaction to a previous infection. The most common initial infections are gastro-intestinal infections, such as salmonella, or genito-urinary infections, such as gonorrhea or chlamydia. It is most common in males in the young adult years. Areas of the body most involved include the eyes, the urinary tract, the cervix in females, and the joints. Asymmetrical involvement of large synovial joints is most common.

Treatment for reactive arthritis includes antibiotics for the original infection and pain relief for the arthritis. Chronic arthritis and heart disease are possible if reactive arthritis is not treated.

8.4 – Resource 14 – Khan Academy – Reiter’s Syndrome

8.4.7 Gout

Gout is a disorder of metabolism that is associated with an excess or uric acid in the body. This uric acid crystalizes into needle-like crystals and lodges in the joints. Males are more often affected than females and the disorder tend to be most common in older individuals. Positive family history, being overweight, and consuming a diet that is heavy in alcohol and meats are considered risk factors for the developing gout. An association between metabolic syndrome and gout has been established.

The most common first joint affected is the metatarsal phalangeal joint of the big toe, but any joint can be affected. Attacks develop very quickly and may be associated with physical or psychological stress or trauma. Joints affected by gout appear red, swollen, and warm. Unrelenting, extreme pain is the hallmark of gout. Uric acid crystals can coalesce and become hard in the joints. These deposits are known as tophi. Gout can lead to continual arthritic pain in the joints and kidney failure.

Treatment includes lifestyle changes, mainly to decrease the intake of purines which break down to uric acid in the body. Meat and alcohol consumption should be decreased or eliminated. Anti-inflammatory medications and steroids are used to decrease the inflammation and pain in the joints. Other pain reducing medications can also be used. Prophylactic drugs that reduce the uric acid levels in the blood are helpful once a flare is over.

8.4 – Resource 15 – Khan Academy – Gout and pseudogout

8.4.8 Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) / Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis (JRA)

This form of arthritis is a noninfective arthritis that appears in children under the age of 16. Most often, it is diagnosed in young children, but can also emerge in adolescence. Girls are affected at a higher rate than boys. Any number of joints can be involved in JIA, and the categorization of types of JIA is noted in the following list.

- Pauciarticular: 50% of cases, 4 or fewer joints involved; relatively mild

- Polyarticular: 30-40% of cases, more than 4 joints involved; moderately severe

- Systemic (Still’s disease): 10-20% of cases, Systemic; fever, rash, eye involvement; most severe

Genetic predisposition is a major factor in the development of the disease, but there is most likely an environmental trigger or infectious process that causes the disorder to appear. The process is an autoimmune type, where destruction of the joints and other organs occurs through the body’s own immune system.

The signs and symptoms of JIA include joint inflammation, stiffness and pain that lasts more than 6 weeks. All joint structures can be affected, and especially in the case of Still’s disease, involvement includes other organs. The eyes, skin, spleen, heart, and liver can all be involved. Many patients with JIA are also anemic.

Management of JIA includes pharmacological suppression of the immune system, NSAIDs, disease-modifying medications, and corticosteroids. Physical therapy is important in the treatment of JIA, consisting of ROM, exercise, and pain control. PTs and PTAs can employ interventions to assist with functional mobility, endurance, and strengthening. Modalities, splints, and orthotics can be useful, as well. Surgical soft tissue releases, osteotomies, and arthroplasties are sometimes necessary for severe joint involvement.

The eventual outcome of JIA is dependent upon the type and severity of the disease. Some patients “outgrow” JIA, seemingly unaffected as adults. Other people are affected with joint pain and other systemic complications throughout life.

8.4.9 Other Forms of Arthritis

Arthritis is associated with many different pathologies. Lyme disease, psoriasis, and systemic lupus erythematosus are sources of joint inflammation and destruction. Their pathophysiologies are discussed elsewhere in this text. For the PTA, the interventions for most arthritic conditions will be similar. It is necessary for physical therapy interventions to address pain, mobility, and endurance in assisting patients to improve participation levels in work and recreational activities.

8.5 Conditions Affecting Muscle

8.5.1 Myopathy

Myopathy is a term used to refer to disease of muscle that leads to muscular weakness. Many different pathologies can cause a myopathy. Some of these include: endocrine, inflammatory, paraneoplastic, infectious, drug- and toxin-induced, critical illness myopathy, metabolic, collagen related, and myopathies with other systemic disorders. Myopathies can be inherited, such as muscular dystrophy, mitochondrial myopathy, or dermatomyositis. Others are acquired, such as drug-induced myopathy (often from overuse of steroids) or alcohol-induced myopathy. For an excellent tutorial on Duchene’s muscular dystrophy, which is the most common form of muscular dystrophy, please check out this video.

Treatments for the various myopathies are specific to the cause of the disease. Physical therapy can be beneficial to patients with myopathy to help strengthen weak muscles, improve muscular stability, improve patterns of movement, improve functional abilities, and increase cardiovascular endurance. Assistive devices, such as canes, crutches, and walkers might be necessary for ambulation. Splinting and bracing might also be employed to help maintain stability and alignment in joints.

8.5.2 Inflammatory Myopathies

There are four major groups of inflammatory myopathies: dermatomyositis, polymyositis, inclusion body myositis (IBM), and necrotizing autoimmune myopathy. These disorders are believed to be autoimmune conditions with no known cause. All can affect adults and children, although dermatomysitis most often affects children and IBM most often affects people over the age of 50. Females are more often affect than males in both polymyositis and dermatomyositis. All inflammatory myopathies are considered rare conditions.

Signs and symptoms common for all forms include muscle weakness which progressively attacks skeletal muscles in a bilateral, proximal-to-distal pattern. Muscle fatigue, incoordination (tripping, falling), and swallowing difficulties are signs in all four disorders. Dermatomyositis includes a skin rash, in addition to the muscle weakness.

Inflammatory myopathies are treatable disorders with variable outcomes. Interventions usually include physical therapy to slow or diminish muscle atrophy and maintain strength and range of motion. Corticosteroid and immunosuppressive drug therapies are incorporated to decrease inflammation and autoimmune activity, respectively.

The prognosis for dermatomyositis is generally good, with approximately one third of patients recovering completely, one third progressing to a relapsing-remitting disorder, and one third facing chronic myositis. Polymyositis can vary, with some people responding well to drug therapies and PT, while others have life-long disability from the disease. IBM generally does not respond to current therapy regimes. Necrotizing autoimmune myopathy usually requires long-term immunosuppressive therapy, but does not impose severe disability.

**Test your knowledge of musculoskeletal disorders by completing the following drag-n-drop.

Inherited Myopathies: Muscular Dystrophy

There are many types of muscular dystrophy; all are inherited conditions in which genes interfere with protein production necessary for the formation of normal muscle tissue. All cause progressive loss of muscle tissue and mass. The most common type of muscular dystrophy is Duchene’s Muscular Dystrophy, which is an X-linked condition, carried by females and expressed in male offspring. For complete description, including videos, of Duchene’s Muscular Dystrophy, see Chapter on Genetic and Developmental Disorders.

Fibromyalgia

https://www.osmosis.org/learn/Fibromyalgia

View the Osmosis video above to gain understanding of fibromyalgia, which is a condition that is not well understood. It includes symptoms of widespread pain: pain in all 4 body quadrants and/or pain in at least 11/14 tender points throughout the body. The location of pain may vary day to day, making it difficult for health care professionals to understand the source of pain. If the pain persists for 3 months, without other known cause, the diagnosis of fibromyalgia can be applied.

Besides pain, patients who are diagnosed with fibromyalgia also often complain of any of the following signs and symptoms:

- fatigue

- disordered sleep

- headache

- “fibrofog” (lack of clarity of thought)

- digestive disorders

- emotional disorders (depression/anxiety)

Fibromyalgia often first appears following a traumatic event, either physical or emotional. Its onset is sometimes associated with infection, such as viral infection. The vague and misleading symptoms often cause the patient to experience frustration in getting a diagnosis, as it can take many months to determine that the symptoms are caused by fibromyalgia.

There is no cure for fibromyalgia, but it can be managed. Pharmaceuticals to help with sleep, decrease pain, and improve mood are often prescribed. Patients often get emotional support or psychological services to help them learn to live with the pain. Physical therapy can be useful in helping improve muscle strength, cardiovascular endurance, and range of motion. Aquatic therapy in a warm-water pool provides an excellent medium for exercise, as it helps support against gravity and it provides even pressure on body surfaces. People who have fibromyalgia generally dislike cold therapies, and enjoy warmer temperatures.

Rhabdomyolysis

Rhabdomyolysis is a condition in which muscle breaks down, releasing the contents of muscle cells in to the extracellular spaces and blood stream. These released contents cause muscle pain (myalgia), muscle fatigue, and swelling in and around the muscle.

The development of rhabdomyolysis is associated with any of the following factors:

- musculoskeletal trauma

- overexertion

- infection (bacterial, viral, including Covid)

- immobility for an extended period of time

- compartment syndrome, or other condition causing muscular ischemia

Musculoskeletal Disorders Resources:

Section 8.1

Resource 01 – Types of Fractures – “File:612 Types of Fractures.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

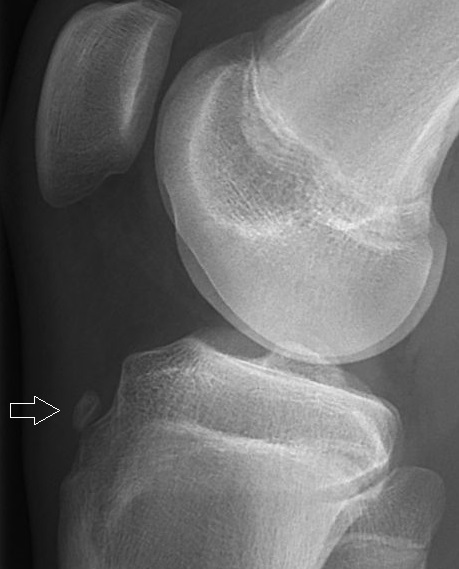

Resource 02 – Avulsion Fracture of the tibial tuberosity in 15 year-old male – “File:Avulsion fracture of tibial tuberosity, annotated.jpg” by Mikael Häggström is in the Public Domain, CC0

Resource 03 – X-ray of periosteal reaction of a stress fracture of the radius – “File:X-ray of periosteal reaction of a stress fracture of the radius.jpg” by Mohamed Jarraya, Daichi Hayashi, Frank W. Roemer, Michel D. Crema, Luis Diaz, Jane Conlin, Monica D. Marra, Nabil Jomaah and Ali Guermazi is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Resource 04 – Internal fixation in the tibia

Resource 05 – External fixation in the forearm and hand

Resource 06 – Surgical decompression of compartment syndrome – “File:Fasciotomyforearm.jpg” by TPompert is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Resource 07 – Basic anatomy of bone – “File:Bone cross-section.svg” by Pbroks13 is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Resource 08 – Strain of gastrocnemius and sprain of anterior talo-fibular ligament

Resource 09 – Sprained ankle tears tendons and ligaments. By Wade Shumaker

Resource 10 – Ankle Sprain – “File:Ankle Sprain.jpg” by hor Injurymap is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Resource 11 – 4 days after a pulled hamstring – “File:2010-10-02 pulled hamstring.jpg” by Daniel.Cardenas is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Resource 12 – Achilles tendonitis – “File:Achilles tendonitis.svg” by Injurymap is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Resource-13 – FXNL Media – Tendinitis, Tendinosis, Tendinopathy?

Resource 14 – Bursitis of the elbow – “File:Bursitis Elbow WC.JPG” by en:User:NJC123 is in the Public Domain

Resource 15 – Illustration of a normal bursa and an inflamed bursa (bursitis) – By Wade Shumaker

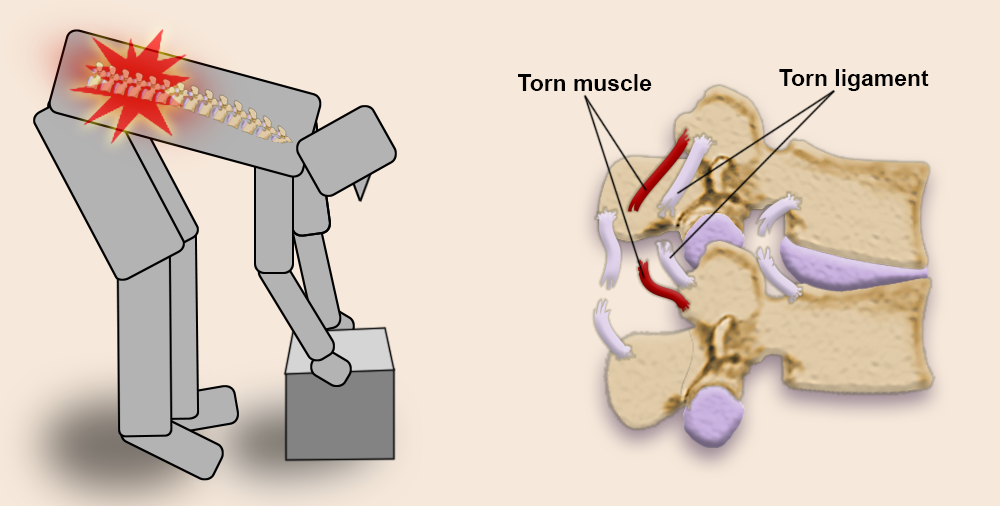

Resource 16 – Illustration: a person bending over to lift a box hurts their back. 2 vertebrae show torn muscles and ligaments. – By Wade Shumaker

Section 8.2

Resource 01 – Age and Bone Mass Graph – “File:615 Age and Bone Mass.jpg” by Author Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Resource 02 – Photo of seated senior citizen with leg cast from toes to mid thigh. – Renee Borromeo, Own work

Section 8.3

Resource 01 – Elderly person walking – OsteoCutout – “File:OsteoCutout.png” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 02 – Feature Osteoprosis of Spine – “File:722 Feature Osteoprosis of Spine.jpg” by Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site, OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Resource 03 – Xray Rickets legs – “File:XrayRicketsLegssmall.jpg” by Mrich is licensed under CC BY-SA 1.0

Resource 04 – Scheuermann’s disease in x-ray – “File:Scheuermanns70.jpg” by Daniel McFadden is in the Public Domain

Resource 05 – LCP in x-ray; Note the destruction of the femoral head on the right side of the x-ray – “File:Roe-perthes.jpg” by J. Lengerke, Praxis Dr. Lengerke is in the Public Domain

Resource 06 – Calcaneal apophysitis in Sever’s Disease – “File:Sclerosis and fragmentation of the calcaneal apophysis.jpg” by Mikael Häggström is in the Public Domain, CC0

Resource 07 – Radiograph of human knee with Osgood Schlatter disease – “File:Radiograph of human knee with Osgood–Schlatter disease.png” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 08 – Blue sclera in Osteogenesis Imperfecta – “File:Characteristically blue sclerae of patient with osteogenesis imperfecta.jpg” by Herbert L. Fred, MD and Hendrik A. van Dijk is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 09 – Bowing and fractures seen in osteogenesis imperfecta – “File:XrayOITypeV-Audult.jpg” by ShakataGaNai is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5

Section 8.4

Resource 01 – Khan Academy – What is arthritis?

Resource 02 – Osteoarthritis Hip – “File:0910 Oateoarthritis Hip A.png” by CFCF is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Resource 03 – Bouchards nodes – “File:Heberden-Arthrose.JPG” by Drahreg01 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 04 – Osteoarthritis in the knee – “File:Osteoarthritis left knee.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 05 – Swan neck deformities of fingers in RA – “File:Swan neck deformity in a 65 year old Rheumatoid Arthritis patient- 2014-05-27 01-49.jpg” by User:Phoenix119 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 06 – Butonierre deformity in RA – “File:RA hand deformity.JPG” by Prashanthns is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 07 – X-ray of RA with unaffected carpal bones Rheumatoid arthritis with unaffected carpal bones 2009 – “File:Rheumatoid arthritis with unaffected carpal bones 2009.jpg” by Mikael Häggström is in the Public Domain, CC0

Resource 08 – X-ray of RA with ankylosed carpal bones, 8 years later Rheumatoid arthritis with fusion of the carpal bones 8 years later in the right image – “File:Rheumatoid arthritis with carpal ankylosis 2017.jpg” by Mikael Häggström is in the Public Domain, CC0

Resource 09 – Khan Academy – Osteo vs. rheumatoid: symptoms

Resource 10 – Khan Academy – Osteo vs. rheumatoid: pathophysiology

Resource 11 – Cervical Spine MRI showing degenerative changes close up – “File:Cervical Spine MRI showing degenerative changes closeup.jpg” by Stillwaterising is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 12 -The ankylosis process – “File:Ankylosing process.jpg” by User:Senseiwa is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Resource 13 – Khan Academy – Infectious Arthritis

Resource 14 – Khan Academy – Reiter’s Syndrome

Resource 15 – Khan Academy – Gout and pseudogout

Section 8.5

Resource 01 – Grotton’s papules in dermatomyositis – “File:Dermatomyositis.jpg” by Author Elizabeth M. Dugan, Adam M. Huber, Frederick W. Miller, Lisa G. Rider is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0