Chapter 5: The Respiratory System

rlb18

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the learner should be able to explain and discuss:

- General pulmonary anatomy and physiology

- Data collection, tests and measures for respiratory conditions

- General signs, symptoms, and effects of pulmonary and respiratory disease

- Infections of the respiratory system

- Explain effects, pathophysiology, and likely outcomes of pneumonia

- Explain effects, pathophysiology, and likely outcomes of tuberculosis

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Describe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Compare causes, chronic bronchitis and emphysema

- Restrictive lung disease

- Explain effects, pathophysiology, and likely outcomes of restrictive lung disease

- Give examples of restrictive lung disease

- Asthma

- Cystic fibrosis

- Lung cancer

- Medications commonly used to treat pulmonary conditions

- The role of the physical therapist assistant in pulmonary conditions

Chapter Contents

- 5.0 General Anatomy and Physiology Review

- 5.1 Breathing

- 5.2 Pulmonary Capacity

- 5.3 Respiratory Rates

- 5.4 General signs of pulmonary system condition or disease

- 5.5 Data Collection, Tests and Measure

- 5.6 Pulmonary Diseases and Conditions

- 5.6.1 General

- 5.6.1.1 Pneumothorax

- 5.6.1.2 Atelectasis

- 5.6.1.3 Pleural Effusion

- 5.6.1.4 Pulmonary Embolism

- 5.6.1.5 Respiratory Acidosis

- 5.6.1.6 Respiratory Alkalosis

- 5.6.1.7 Bronchiectasis

- 5.6.2 Infectious Lung Diseases

- 5.6.2.1 Pneumonia

- 5.6.2.2 Tuberculosis

- 5.6.3 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- 5.6.3.1 Chronic Bronchitis

- 5.6.3.2 Emphysema

- 5.6.4 Restrictive Lung Disease

- 5.6.5 Other Pulmonary Conditions

- 5.6.5.1 Asthma

- 5.6.5.2 Cystic Fibrosis

- 5.6.5.3 Lung Cancer

- 5.7 Medications Commonly Used to Manage Pulmonary Conditions

- 5.8 Pulmonary Conditions and the PTA

5.0 General Anatomy and Physiology Review

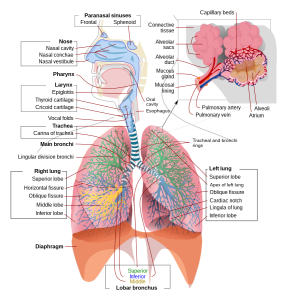

The pulmonary, or respiratory system, is a vital body system. The pulmonary and cardiovascular systems work together to bring oxygen into the body and distribute it throughout the body, and then release carbon dioxide and water from the body. The main components of the upper and lower respiratory tracts are shown below. The upper respiratory tract consists of all structures above the vocal folds: the nose and mouth, paranasal sinuses, pharynx, and larynx. The lower respiratory tract includes all those below the vocal folds: the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli.

Long Description

The illustration shows the following groups

- Paranasal sinuses

- Frontal

- Sphenoid

- Nose

- Nasal cavity

- Nasal conchae

- Nasal vestibule

- Pharynx

- Larynx

- Epiglottis

- Thyroid cartilage

- Cricoid cartilage

- Vocal folds

- Trachea

- Carina of trachea

- Main bronchi

- Lingular division bronchi

- Right lung

- Superior lobe

- Horizontal fissure

- Oblique fissure

- Middle lobe

- Inferior lobe

- Diaphragm

- Lobar bronchus

- Superior

- Inferior

- Middle

- Capillary beds

- Connective tissue

- Alveolar sacs

- Alveolar duct

- Mucous gland

- Mucosal lining

- Pulmonary artery

- Pulmonary vein

- Alveoli

- Atrium

- Tracheal and bronchi rings

- Left lung

- Superior lobe

- Apex of left lung

- Oblique fissure

- Cardiac notch

- Lingula of lung

- Inferior lobe

- Oral cavity

- Esophagus

For a review of the pulmonary system, please watch the following video.

5.0 – Resource 02 – “The lungs and pulmonary system | Health & Medicine | Khan Academy” by Khan Academy is licensed under Fair Use

5.1 Breathing

Breathing is accomplished by a combination of muscle activity and pressure gradients. When the diaphragm contracts, it pulls downward, elongating the pleural space. When the intercostal muscles contract, they pull the pleural cavity upward and outward. The result of this muscle action is that the pleural space and lung volume increase. This increase in volume creates a decrease of pressure inside the lungs relative to the air pressure outside the body. Since gasses always flow from an area of greater pressure to an area of lower pressure, air flows into the lungs. This is inspiration.

During expiration, the diaphragm returns to its upward position, and the relaxing intercostal muscles allow the ribs and lungs to return to the resting position. This decreases the lung volume, thereby increasing the pressure in the lungs, so the air rushes out to an area of lower pressure outside the body. For a good video explanation of this activity, watch this:

5.1 – Resource 01 – The Mechanisms of Breathing

To watch a real time video of breathing visualized through MRI, check out the link below:

5.2 Pulmonary Capacity and Volume

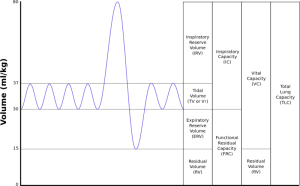

Refer to the chart below for a visual representation of breathing and lung capacities.

Long Description

Graph of lung volumes.

A graph shows Lung Volumes where the Y axis is Volume in milliliters per kilogram and goes from 0 to 80 with horizontal lines at 15, 30 and 37. The X axis has no units. A sinusoidal curve oscillates 4 times between 30 and 37, then has a larger oscillation between 15 and 80 then has 2 more between 30 and 37.

Sections of the graph:

- 0 to 80: Total lung capacity (TLC)

- 15 to 80: Vital capacity (VC)

- 0 to 15: Residual volume (RV)

- 30 to 80: Inspiratory capacity (IC)

- 0 to 30: Functional residual capacity (FRC)

- 37 to 80: Inspiratory reserve volume (IRV)

- 30 to 37: Tidal volume (TV) or (V sub T)

- 15 to 30: Expiratory reserve volume (ERV)

- 0 to 15: Residual volume (RV)

Regular relaxed breathing is the tidal volume of breathing. It includes gentle inspiration and expiration. If you take a really big breath in, the volume of air above the normal tidal volume inspiration is the inspiratory reserve volume. If you include the inspiratory volume that is part of the tidal volume, the total amount of inspiration is the inspiratory capacity. The amount of air that you are able to exhale after your normal expiration phase of the tidal volume is the expiratory reserve volume. As long as we are alive, there is a small amount of air that stays in the lungs, so that they do not deflate completely. This is the residual volume. If the expiratory reserve volume is added to the residual volume, the result is the functional residual capacity. The vital capacity includes the inspiratory capacity and expiratory reserve volume, which means a maximal inspiration plus a maximal expiration. If you add the reserve volume to the vital capacity, the result is the total lung capacity. The chart below will be helpful to refer to when learning about some pulmonary conditions and diseases.

5.3 Respiratory Rates

Respiratory rates are counted in breaths per minute (bpm) during times of quiet respiration. During infancy and childhood, normal respiratory rates are considerably higher than for an adult. If the pulmonary system is working well, the chest and abdomen should gently rise and fall in a rhythmic pattern. The shoulders should remain level, and there should be no signs of stress or strain with breathing.

Normal Respiratory Rates (bpm) for various ages

| Age | Rate |

|---|---|

| Adult | 12-20 |

| 16-year old | 15-20 |

| 3-year old | 20-30 |

| Newborn | 25-50 |

5.3 – Resource 01 – Normal Respiratory Rates (bpm) for various ages

5.4 General signs of pulmonary system condition or disease

- Sneeze: irritation or inflammation of nasal passages

- Cough:

- Irritation due to nasal discharge

- Inflammation, foreign material, or tumor in lower respiratory tract

- Effectiveness is determined by strength of respiratory muscles

- Productive or unproductive

- Hemoptysis

- Dyspnea: Subjective feeling in which the patient feel unable to inhale enough air

- Orthopnea: dyspnea in supine

- Tachypnea: breathing at a faster rate than expected

- Bradypnea: breathing at a slower rate than expected

- Chest pain: may radiate to shoulder or arm

- Cyanosis

- Central: mucous membranes of mouth, lips

- Peripheral: nail beds, nose, ends of fingers, toes

- Altered or irregular breathing patterns

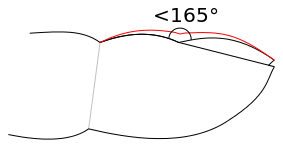

- Clubbing of fingernails: shape of nailbed changes; angle is flattened out (> 180 degrees); seen in pulmonary and cardiovascular disorders; can be hereditary; associated with enlarged capillary bed

5.4 – Resource 01 – Cyanosis of the fingers

5.4 – Resource 02 – Clubbing Fingers or Acopaquia

5.4 – Resource 03 – Clubbing in the fingernails. Note the change in angle of the nailbed. –

5.5 Data Collection, Tests and Measures

There are many tests and measures to help determine the state of the pulmonary system. Some can be observed or performed during a physical therapy treatment session, while others are performed by other health care professionals. PTAs should be aware of the many tests and the implications of the results for PT interventions.

- Subjective

- Dyspnea: patient’s complaint of feeling short or breath

- Fatigue:

- Objective

- Respiratory rate

- Tachypnea: breathing is at a higher rate than expected

- Bradypnea: breathing is at a lower rate than expected

- Breathing pattern

- Diaphragmatic: normal use of diaphragm and intercostals, contractions for inspiration, relaxation for expiration

- Accessory muscle use: Patients might use accessory muscles in the chest and neck to help with breathing. Common accessory muscles used for inspiration are the sternocleidomastoids, scalenes, pectoralis major and minor, trapezius, erector spinae, and latissimus dorsi. The abdominal muscles can be used for forced expiration.

- Apnea: absence of breathing

- Hypopnea: shallow breathing

- Hyperpnea: fast, deep breathing (normal during exercise)

- Paradoxical breathing: occurs in multiple rib fractures, such that a portion of the rib cage is separated; associated with flail chest; part of the rib cage is sucked inward during inspiration, as the diaphragm pulls downward; during expiration the same part distends

- Indrawing/intercostal indrawing: lower ribs pulled in with inspiration; seen in pneumonia and other pulmonary conditions

- Ataxic: uncoordinated breathing pattern

- Apneustic: abnormal breathing pattern characterized by a deep, gasping inspiration, followed by a short pause and then a short incomplete expiration; associated with brain damage

- Cheyne-Stokes: patterns of quick breaths followed by periods of apnea, associated with brain damage or heart failure.(This term is used interchangeably with Biot’s respiration in some sources.)

- Biot’s respiration: groups of shallow, quick breaths followed by periods of regular or irregular apnea; occurs with brain damage as in head injury or stroke, or as a result of opioid overdose

- Kussmaul breathing: Deep labored, gasping breathing associated with metabolic acidosis

- Cough

- Effective or ineffective

- Productive or non-productive for sputum

- Insidious or acute onset

- Chronic, frequent, infrequent

- Sounds: dry, barking,

- Sputum

- Assessed for amount produced, color, consistency

- Clear, translucent: normal

- Purulent: greenish; large numbers of white blood cells, as in infection

- Blood-tinged/ hemoptysis: associated with TB, lung cancer, or irritated pulmonary structures

- Carbon particles in the sputum

- Gray in smokers

- Black in coal miners

- Heart rate: most likely to increase in association with pulmonary disorders. This is a compensatory strategy for the body to get more oxygen distributed

- Breath sounds

- Crackles (rales): fine, rattling, or crackling noises heard through auscultation; associated with alveoli that are closed due to fluid, mucous, or lack of aeration “popping open” during inhalation; heard in many pulmonary conditions

- Wheeze: course, whistling sound heard on inspiration and/or expiration; associated with obstruction or narrowing of any part of the bronchial tree; may be heard with or without stethoscope

- Stridor: high-pitched sound associated with obstruction in the larynx or lower bronchial tree; associated with croup in children, epiglottitis, foreign body aspiration, and tumor obstruction

- Pleural rub: squeaking sound heard through auscultation; associated with pleural effusion

- Absent: no breath sound heard on auscultation; associated with collapsed lung due to atelectasis or pneumothorax

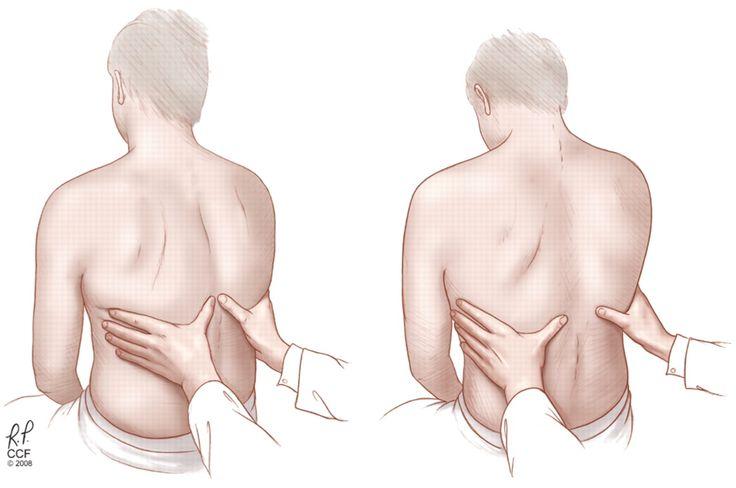

- Chest Excursion/ expansion: ******(missing image)*******

- Respiratory rate

5.5 – Resource 01 – Chest Excursion /Expansion –

- Measurement is taken with tape measure around the level of the 6th rib. Positive result yields < 2.5 cm, or 1 inch, excursion from maximal exhalation to maximal inhalation; associated with restrictive lung disease, or other lung condition; also seen in ankylosing spondylitis.

- chest expansion test

- Alternate measure for chest excursion: Hands placed at T9-10, as show; patient inhales; clinician’s hands should follow chest movement which is smooth and symmetrical; thumbs should spread 3-5 cm with inspiration.

- Tactile fremitus: patient repeated says “99” as clinician places hands on various areas of the posterior thorax; clinician assess vibrations; helpful in identification of obstruction or pulmonary edema

- Chest shape/symmetry

- Barrel: chest extends in an anterior-posterior direction, causing a circular, or barrel-shaped appearance; occurs in COPD, cystic fibrosis, and other conditions that cause air to remain trapped in the lungs

- Flared: inferior rib widening secondary to long-term distension of the lower lobes of the lungs; occurs in COPD, cystic fibrosis, and other conditions that cause air to remain trapped in the lungs

- Pigeon chest/pigeon breast/pectus carinatum: protrusion of the sternum and chest seen in genetic conditions, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, Trisomy 21, Marfan’s syndrome, and other genetic conditions; little or no effect on breathing

5.5 – Resource 03 – Pigeon chest, Tolson411 – Own work Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0

-

-

Pectus excavatum (Funnel chest): depression of the sternum and chest; seen in genetic conditions, such as Noonan syndrome and Marfan’s syndrome; respiratory and cardiac function can be severely affected by pectus excavatum

5.5 – Resource 04 – Pectus excavatum chest, Author: en:User:The number c, Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0

-

- Spirometry (Incentive inspiratory spirometry): device used to assess inspiration volume; patient instructed to put the mouthpiece in the mouth and take a deep breath in and hold the breath for 2-6 seconds to help open alveoli; objective numerical values for inspiration are on the device; used following surgery, especially with general anesthesia, or in pulmonary conditions

5.5 – Resource 05 – Johntex, CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons - Peak expiratory flow measurement: a peak flow meter measures speed of maximal expiration; patient used a hand-held meter and maximally exhales through the mouthpiece; most often used in cases of pulmonary obstruction; as flow rates will be decreased in the presence of obstruction

5.5 – Resource 06 – Peak flow meter, Melvil, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 - Arterial blood gasses (PaO2 and PaCO2): blood is drawn and percentage of oxygen and carbon dioxide are determined

- Hypoxemia: diminished PaO2; result of hypoventilation

- Hypercapnia: excessive PaCO2; result of hypoventilation

- Hypocapnia: diminished PaCO2; result of hyperventilation

5.5 – Resource 07 – Saturometre: pulse oxymetry device, Rama, Wikimedia Commons, , CeCILL

- Acid/base balance of blood

- 7.35-7.45 pH

- < 7.35 pH: respiratory acidosis (increased PaCO2)

- >7.45 pH: respiratory alkalosis (decreased PaCO2)

- 7.35-7.45 pH

- Chest radiographs, CT scans, MRI: all used to image alterations in the internal structures; can be used with our without contrast materials; useful for visualizing masses or nodules on or in the lungs, bony changes in the ribs, sternum, vertebrae, hypertrophy or atrophy of structures (heart and lungs and structures with them), displacement of organs

- Arteriography (Angiography): contrast medium injected into blood supply and radiography used to visualize blood flow through the area

- Bronchoscopy: tube with a small camera inserted through the trachea and into the lungs to “see” abnormalities within the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles

5.6 Pulmonary Diseases and Conditions

5.6.1 General Conditions

An intact and efficient pulmonary system is essential to health and well-being. When people have difficulty with the mechanisms of breathing, it is often given the general term “respiratory distress.”

Read this article for a great lesson on the signs, symptoms, and reasons for respiratory distress

5.6.1.1 Pneumothorax

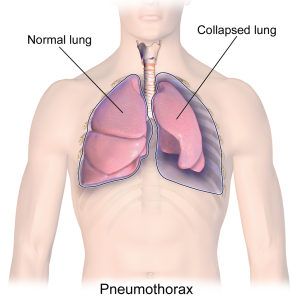

A pneumothorax is often referred to as a “collapsed lung” because it allows a lung to decrease in volume. In a pneumothorax, air accumulates between the lung and the chest wall which presses inward on the spongy lung tissue. This can occur as a result of trauma to the lung, as an associated disorder with other pulmonary conditions (asthma, emphysema, TB, pneumonia, history of smoking), or spontaneously for no apparent reason. When there is no trauma or underlying pathology, the pneumothorax is labeled “primary.” If there is an associated condition or disease, it is labeled “secondary.” If the pneumothorax is associated with an injury or medical procedure, it is labeled “traumatic.”

Signs and symptoms of a pneumothorax include sharp, one-sided chest pain and shortness of breath. A small, primary pneumothorax may require monitoring only as the body heals itself. For a larger pneumothorax, especially in the presence of chronic disease, the excess air is often removed with a syringe or chest tube. Surgery may be required to repair a large pneumothorax. If left untreated, a large pneumothorax can lead to respiratory distress or death. In the infrequent case of tension pneumothorax, a one-way movement of air out of the lung and into the pleural space exists, and lung expansion is impossible. This is a true medical emergency.

5.6.1.2 Atelectasis

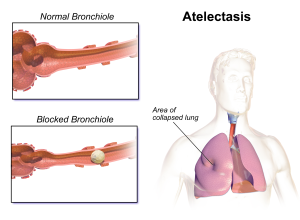

Atelectasis, like pneumothorax, is often referred to as “collapsed lung,” although the pathology is quite different. In atelectasis, the alveoli collapse and gasses are not able to be exchanged through these structures. This can be caused by a blockage in a bronchiole from a mucous plug or other material inside the bronchiole, or from pressure outside the bronchiole, perhaps from a tumor or fluid. In premature infants, the lack of surfactant surrounding the lung tissue can cause atelectasis. Poor production of or distribution of surfactant can also lead to atelectasis in adults. Smoking and underlying pulmonary disease are significant risk factors. Most cases of atelectasis occur during surgical recovery.

Physical therapy can be useful in the treatment of atelectasis. Deep breathing exercises and ambulation activities can help prevent atelectasis. Breathing exercises, coughing, percussion and postural drainage can help loosen and remove mucous plugs associated with atelectasis.

5.6.1.3 Pleural Effusion

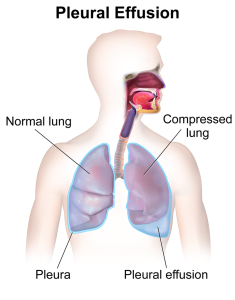

If fluid accumulates in the pleural space, the condition is called pleural effusion. This can occur because of chronic illnesses such as heart failure, kidney failure, or liver cirrhosis. When the normal air space of the lung is compromised by fluid accumulation, there is less space for the lung to expand and move air in and out of the body. This can cause shortness of breath, coughing, and fatigue for the patient. Chest expansion may be diminished over the area of effusion. A pleural rub (squeaking or grating sound) or other abnormal breath sounds may be appreciated through auscultation.

In the case of pleural effusion, the fluid is usually collected via needle biopsy and then tested for infectious agents. The fluid can be drained using a chest tube, if necessary. If infection is present, antimicrobial medications are prescribed.

5.6.1.4 Pulmonary Embolism

A pulmonary embolism (PE) occurs when a piece of a thrombus in the venous system (most often a DVT) breaks off and is carried back to the heart in the blood. Since the veins become larger as they approach the heart, the embolism is carried in the bloodstream through the heart and becomes lodged in a small pulmonary artery in the lung. For a PE to become symptomatic, the embolism must either be very large, or consist of several thrombi that have broken free from venous walls and formed a large blockage in the pulmonary circulation. A PE causes damage to lung tissue by occluding blood flow to the area supplied by a vessel, producing ischemia and tissue death. This dead tissue is unable to perform important gaseous exchanges, and less oxygen is available for circulation throughout the body.

The most important risk factor for PE is DVT. Other risk factors include recent immobilization or surgery, obesity, pregnancy, inherited blood conditions, smoking, estrogen replacement therapy, and heart disease. Signs and symptoms of a PE include dyspnea, chest pain, coughing, and hypoxia. The signs and symptoms can be very similar to those of a heart attack, and either diagnosis should receive immediate attention. Other signs and symptoms may include hemoptysis, lower extremity edema, cyanosis, wheezing, diaphoresis, syncope, and weak, rapid pulse.

Anticoagulation medications, such as heparin and coumadin, are the treatment of choice for patients experiencing PE and/or DVT. Supplemental oxygen may also be required.

5.6.1.5 Respiratory Acidosis

The normal pH of blood is 7.35-7.45. If the pH is below 7.35, and the blood is too acidic, the condition is called acidosis. This can occur because of hypoventilation, in which case it is termed respiratory acidosis. If a patient’s breathing is too slow (bradypnea) or shallow, or breathing is suppressed because of disease or drugs, the lungs are unable to remove adequate amounts of CO2. The CO2 builds up in the blood, which is a state of hypercapnia. The excessive CO2 causes bicarbonate (HCO3-) levels to decrease, and the kidneys try to compensate by releasing extra bicarbonate into the blood.

Respiratory acidosis can be an acute or chronic condition and is a symptom of many different etiologies. Acute respiratory acidosis a medical emergency that is associated with head trauma, cerebral disease, neuromuscular disease, drugs, or airway obstruction, as in COPD or an acute asthma attack. Chronic respiratory acidosis is a secondary condition caused by several conditions, including COPD, neurological disease, interstitial lung disease, pneumonia, obesity, and severe scoliosis.

Treatment of respiratory acidosis is directed at treating the underlying condition causing the acidosis.

5.6.1.6 Respiratory Alkalosis

If the pH of the blood is greater than 7.45, a state of alkalosis exists. Hyperventilation is the most common cause of respiratory alkalosis. Hyperventilation (tachypnea) causes too much CO2 to be released through the pulmonary system, causing a state of hypocapnia. Hydrogen (H+) levels also decrease in this condition. Respiratory alkalosis can occur secondary to many conditions, such as COPD, asthma, pulmonary embolism, hyperthyroidism, and sepsis. It can also be a response to living at high altitudes or as a CNS response to fever, anxiety, pain, or trauma.

Respiratory alkalosis can be an acute or chronic condition. Both types require treatment of the primary source of the hyperventilation.

Complete the following chart for Respiratory Alkalosis and Respiratory Acidosis.

5.6.1.7 Bronchiectasis

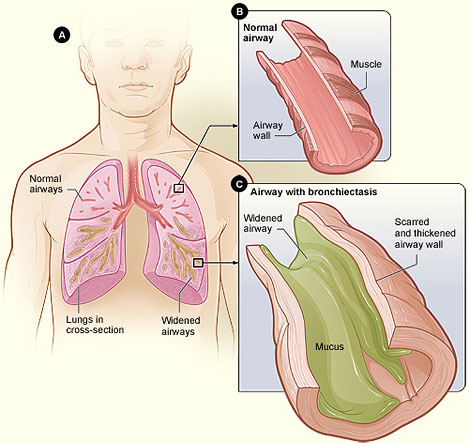

Bronchiectasis is a condition in which the airways of the lungs are permanently widened. It occurs in association with pneumonia, tuberculosis, lung cancer, immunosuppressive disorders, and cystic fibrosis. The breakdown of the airway walls is caused by continual excessive inflammatory responses in the lungs, and the expansion of the airways causes excessive mucus production. This mucus presents fertile ground for infection, especially for bacteria. Patients with bronchiectasis have frequent lung infections and can cough up copious amounts of purulent sputum. This disorder can be categorized as an obstructive disease, but since it is a condition associated with other lung and systemic conditions, it is categorized as a general condition here.

Signs and symptoms of bronchiectasis include cough with mucus production, shortness of breath, coughing up blood (hemoptosis), fatigue, fever and chills during exacerbations. Wheezing, chest pain, and clubbing of the fingers are also possible signs. The progression of bronchiectasis is marked by periods of exacerbation, when symptoms can be more pronounced and hospitalization may be necessary.

Treatment includes pulmonary physical therapy (percussion and postural drainage, breathing exercises, postural correction) and medications. Antibiotics, mucus-thinning medications, and mucus thinning devices, such expiratory pressure devices or Flutter devices (see section on Cystic Fibrosis below), are also useful in eliminating excess mucus. Lung transplantation surgeries are performed in severe cases. It is important that patients with bronchiectasis avoid smoking and are regularly vaccinated for flu and pneumonia.

Review Exercise

5.6.2 Infectious Lung Diseases

5.6.2.1 Pneumonia

Pneumonia is a condition that causes inflammation of one or both lungs, mainly in and about the alveoli. Many different infectious agents can cause pneumonia. Viral and bacterial infections are most common, but fungal and mycoplasma microbes can all cause pneumonia. Pneumonia can be the result of these organisms entering the lungs through inhalation of germs spread through coughing, sneezing, or speaking (community acquired), through insertion of ventilator tubes or other medical instruments (nosocomial). Some forms of pneumonia (histoplasmosis, for example) are acquired from breathing in microbes from soil infected with fungal agents associated with bird or bat droppings. In addition, pneumonia can be an effect of aspiration of food, liquids, or other substances or items.

Patients with pneumonia will most often exhibit a cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, and fever. Pneumonia can be relatively mild or very serious, depending upon the infectious agent and overall health of the individual. In Pneumonia, fluid collects in the areas of infection in the alveoli, which makes it difficult for the O2 and CO2 transfers to occur. The people who are at greatest risk for developing pneumonia are those with weakened immune systems due to comorbities, immobility, poor nutrition, advanced age, and inadequate medical care. A weak or absent gag reflex is also a significant risk factor for aspiration pneumonia. Anytime a breathing tube is inserted, as in surgery, also places a patient at risk for developing pneumonia.

Treatment for pneumonia includes medications directed at eliminating the inciting infection and decreasing the lung inflammation. Percussion and postural drainage may be useful in assisting patients to clear areas of mucous and fluid retention in the lungs. In addition, general mobility and breathing and coughing exercises can be incorporated to help with lung function.

Click this link to watch a video on pneumonia.

Test Your Knowledge

- What are the two most common types of community acquired pneumonia, and what can we do to help prevent them?

- Is pneumonia primarily a problem of obstruction, restriction, ventilation, or perfusion? (Hint: You might want to look back on the Kahn Academy video of Respiratory Distress.)

5.6.2.2 Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease that has been targeted by the CDC to be eliminated by 2100. Unfortunately, efforts toward eradication are behind schedule, and reducing the number of cases in the US and around the world is proving to be challenging. Health care workers are considered an at-risk population because of the possibility of exposure to TB, and the communicability of the disease in the active form. The populations most at-risk for developing TB include those born outside of the US in countries with high incidence of TB and those living in congregate settings (correctional institutions, long-term care facilities, homeless shelters). TB is also more common in people who have diabetes or AIDS, or those whoabuse drugs or alcohol. World-wide, one-quarter of the population is infected with TB, and it is the leading cause of death due to infectious disease. (CDC statistics, obtained August 12, 2018. )

TB is caused by the bacterium Mycobacteruim tuberculosis. It is communicable in the active state through airborne transmission, as in coughing, sneezing, or talking. It most often affects the lungs, but can also affect the kidneys, bone, CNS, lymphatic system, and genito-urinary system. The most common signs and symptoms of the active form of the disease include coughing, hemoptysis (blood-tinged sputum), weight loss, fever, and night sweats. Lung tissue infected with TB will develop areas of caseous necrosis called “granulomas.”

The initial exposure to the TB bacterium is considered the primary infection. Following the primary infection, the bacterium could cause a progressive primary infection, in which the patient would exhibit the signs and symptoms of TB and would be at risk for lung damage or even death. More often, the TB bacterium exists in a latent state (90% of US cases are latent). A person who has the latent form is more likely to develop a reactivation of TB, often called the secondary progressive state, if they experience a depression of the immune system. This might include HIV/AIDs, diabetes, or auto-immune disease. The signs and symptoms of the secondary progressive infection are the same as for the primary progressive infection, at in this state, the affected person is highly contagious.

The Mantoux tuberculin skin test detects the presence of latent or active forms of TB. A positive result on the skin test will be followed up with blood work, which can detect the presence of the TB bacterium. If active TB is suspected, chest x-rays and sputum sample testing are used to determine active disease. TB is only communicable in the active state.

Vaccination is available for prevention of some forms of TB and is routinely given to children in high-risk populations. It is not used in most US-born infants because it can lead to false positive results on the skin test, making that screening tool less valuable.

Treatment of TB includes many months of anti-microbial medications for the patient and family members and caretakers. Some strains of TB are resistant to the most commonly used medications and require very expensive medication regimes, with less optimistic prognoses than the non-resistant forms.

Kahn academy video on TB:

5.6 – Resource 06 – Primary and Secondary TB – Khan Academy

5.6.3 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

5.6.3.1 Chronic Bronchitis

Watch the video on chronic bronchitis:

5.6 – Resource 07 – Chronic Bronchitis – Khan Academy

Chronic bronchitis is a pulmonary condition that affects people who smoke or who are exposed to smoke, air pollution, coal dust, asbestos, or have allergies that constantly irritate the lungs. A diagnosis of chronic bronchitis is given when a person has a productive cough for 3 consecutive months for 2 consecutive years. The hallmark of this condition is excessive mucous production that is a response to irritation of the bronchioles, which are inflamed. Because of this over-production of mucous, airways can become plugged with mucous and breathing becomes difficult. Expiration is more difficult than inspiration and the residual volume of the lungs increases, while the tidal volume and inspiratory volumes decrease. Also, air exchange is less efficient, so the amount of oxygen in the blood will be less than optimal (hypoxia), and the amount of CO2 will be higher than normal. The oxygen saturation deficiency will show up in pulse oximetry and the nailbeds and lips can take on a bluish tone (cyanosis). Air is trapped in the lungs because of the mucous plugs, so over time, the chest can become larger, and take on a barrel shape. Because of the bluish coloration and the enlarged chest, patients with chronic bronchitis are often referred to as “blue bloaters.”

Chronic bronchitis is a chronic disease, but acute episodes are not uncommon. These episodes include increased mucous production and coughing and can be caused by further irritation of the bronchioles from a cold, allergies, or other increased irritation.

The most important treatment for chronic bronchitisis to decrease the source of irritation. If the patient is a smoker, they should stop smoking. Exposure to other allergens or environmental irritants should be avoided, if possible. Corticosteroids (e.g. Prednisone) are prescribed to decrease the swelling and inflammation of the bronchiole walls and bronchodilators are employed to open the bronchioles. Sometimes, supplemental oxygen therapy is used to help raise the oxygen saturation rates. During acute attacks, antibiotics are prescribed to decrease the risk of developing pneumonia. All patients with chronic bronchitis should receive flu and pneumonia vaccines. Percussion and postural drainage may be useful in clearing mucous plugs. Patients also can benefit from breathing exercises and general physical conditioning.

5.6.3.2 Emphysema

Watch the following video on emphysema.

5.6 – Resource 08 – What is Emphysema – Khan Academy

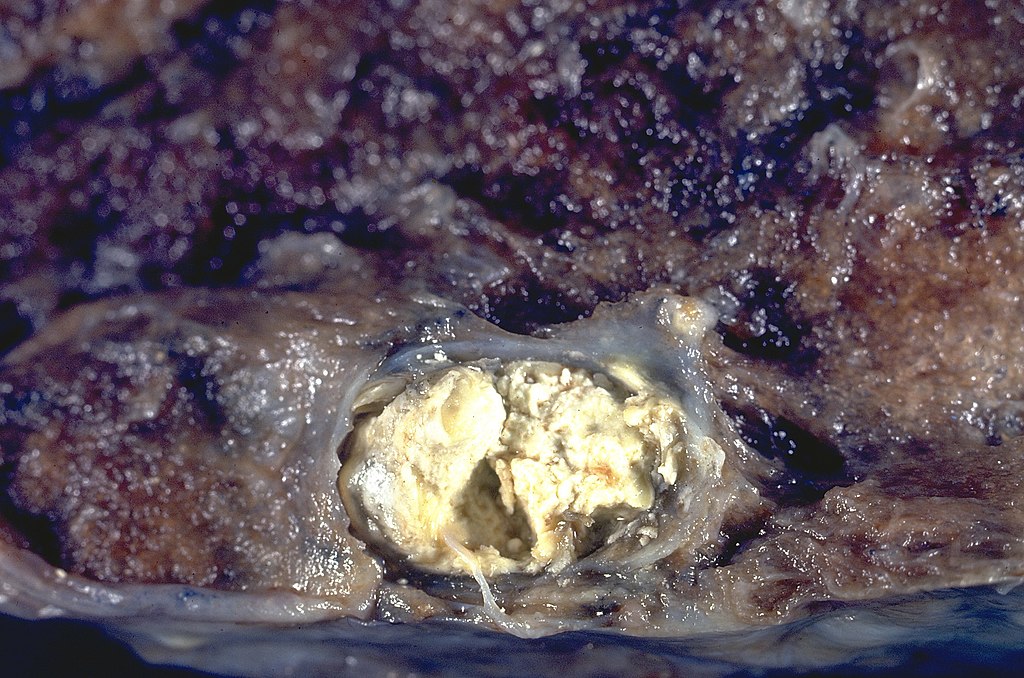

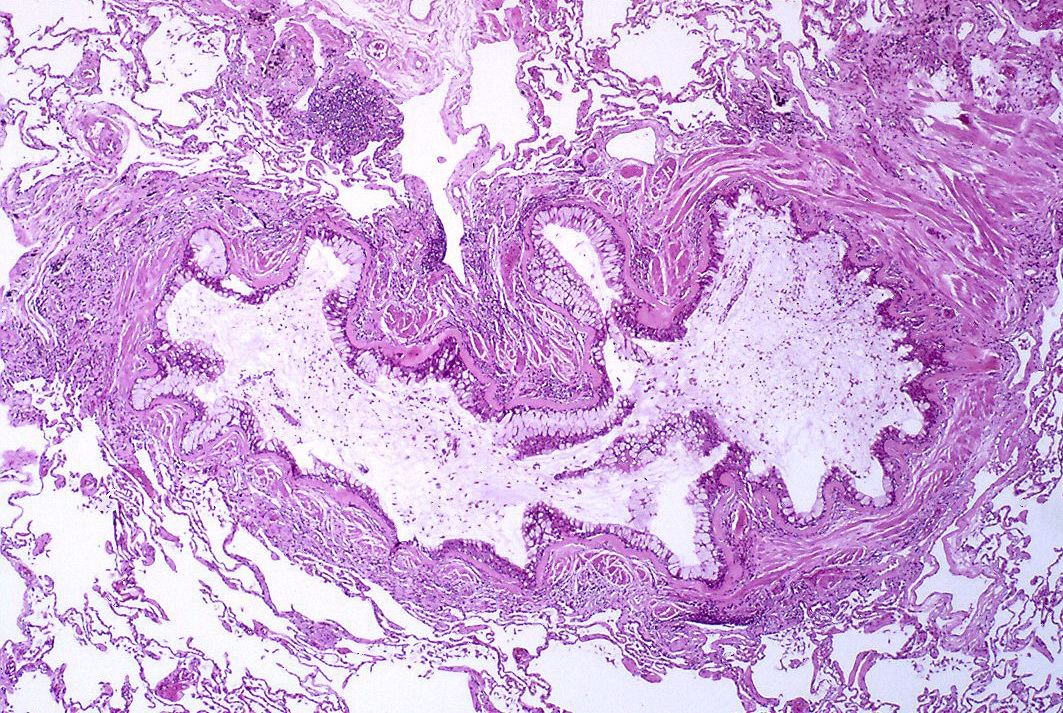

The other pulmonary disorder that is included in every COPD discussion is emphysema. Emphysema is similar to chronic bronchitis in that the main problem is one of obstructed breathing and air exchange. Both are highly associated with smoking, but the pathophysiology is quite different. Emphysema is the result of the loss of elastin in the alveoli structures. This causes these important structures to collapse, making oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange very difficult. Air pockets, known as blebs, form between the alveolar spaces. Air pockets can also form in the lung parenchyma; these are called bullae.

The oxygen delivery into the lung is less affected than the removal of the CO2, so people with emphysema do not tend to be cyanotic. They develop coping mechanisms, which include increasing breathing rate, but not depth of breathing. Over time, they develop a barrel chest, and they will often assume a pursed-lip breathing pattern. Because of these characteristics, people with emphysema are sometimes referred to as “pink puffers.” People with emphysema also develop wheezing, dyspnea, and centralized chest pain, and they can develop right-sided heart failure as congestion backs up from the lungs to the right side of the heart.

Gross pathology of lung showing centrilobular emphysema characteristic of smoking. Closeup of fixed, cut surface shows multiple cavities lined by heavy black carbon deposits.

Risk factors for emphysema include smoking or exposure to second hand smoke, chronic bronchitis, respiratory infections, and genetic factors. Environmental factors, such as exposure to coal dust, asbestos, or air pollution also contribute to the development of emphysema. Treatment of emphysema includes smoking cessation and daily use of bronchodilators. During acute exacerbations, antibiotics and steroids are used. Supplemental oxygen might be beneficial, also. All patients with chronic bronchitis should receive flu and pneumonia vaccines. Percussion and postural drainage may be useful in clearing mucous plugs. Patients also can benefit from breathing exercises and general physical conditioning.

5.6.4 Restrictive Lung Disease

Restrictive lung disease is a condition in which lung expansion is limited, most often because of infiltration of fibrotic tissue in the lungs. Specific conditions that can cause scaring and fibrosis include Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), infant respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS), radiation fibrosis, and pneumoconiosis (long term exposure to irritants, such as coal dust, asbestos). Structural problems, such as scoliosis, kyphosis, and obesity can also lead to restrictive lung disease. Inspiration is a greater problem than expiration in restrictive lung disease and total lung capacity is decreased. Forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume are also decreased. Symptoms of the disorder include dyspnea and coughing.

Treatment for restrictive lung disease focuses on the source of the problem. For infections causing restriction, antimicrobial medications can be utilized. For structural or postural issues, postural training, muscular training, and orthopedic surgeries can be helpful. Most patients with restrictive lung disease will benefit from breathing exercises and general conditioning. For some patients, lung transplantation or heart-lung transplantation is a good option.

5.6.5 Other Pulmonary Conditions

5.6.5.1 Asthma

Asthma is a common disorder that can be quite variable in severity. Asthma attacks can occur with extreme variation in frequency. Most people who have asthma can manage the chronic illness with lifestyle modifications and medications, but sometimes attacks can be acute and severe with life-threatening symptoms.

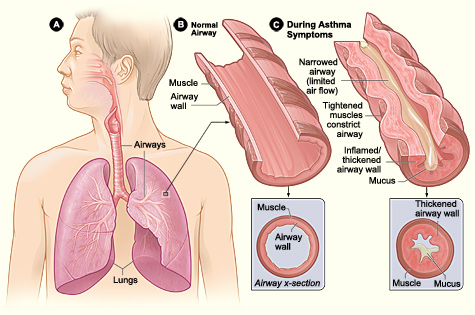

The cause of asthma is not known, but the incidence of asthma in the US has risen steadily in the past 50 years. There are some common triggers for asthma attacks: smoke, pollen, dust, perfumes or other chemicals, animal dander, mold, air pollution, aspirin, certaon foods, exercise, and stress are among the most common. When a person is exposed to a trigger or allergen, the body produces a strong immune reaction, mobilizing large numbers of mast cells containing histamine to the lungs. The smooth muscle in the bronchioles constricts and the mucosal layer of the inner walls of the bronchioles swells, narrowing the lumen. Extra fluid and mucous are released into the bronchioles, which narrows the lumen even more. Breathing becomes difficult and the irritated airways cause coughing. Wheezing, generally on exhalation, can be heard through auscultation, and even sometimes without the use of a stethoscope. Asthma is a disorder of obstruction, so exhalation is affected more acutely than inspiration, and CO2 builds up in the lungs and in the blood.

Long Description

Asthma attack

The illustration shows 3 parts.

- Part A: the lungs of a transparent person.

- Airways and lungs are labelled;

- Part B: A normal airway.

- Muscle and airway walls are labelled;

- Part C: During Asthma symptoms.

- The airway is extremely reduced from mucus.

- The following are labelled:

- narrowed airway (limited air flow);

- tightened muscles constrict airway;

- inflamed/thickened airway wall; mucus.

Asthma is managed through avoidance of known triggers and preventive measures. Many patients have inhalers or nebulizers which deliver inhaled steroids or bronchodilators, such as albuterol. These are useful prior to exercise (think physical therapy) to prevent attacks. Patients use some medications for short term relief from attacks. Some patients also use longer-acting medications for management of the chronic condition. There is no cure for asthma, although some children “outgrow” the condition. Medications are useful in treating the symptoms. There are rare times when a patient is non-responsive to the usual medications and they can enter a life-threatening state of acute severe asthma attack (previously called status asthmaticus). This is a medical emergency, and large amounts of medications are administered to decrease the pulmonary edema and mucous production, reduce the bronchospasm, and improve O2 levels in the blood.

5.6 – Resource 13 – What is Asthma? Khan Academy

5.6 – Resource 14 – Asthma pathophysiology – Khan Academy

5.6.5.2 Cystic Fibrosis

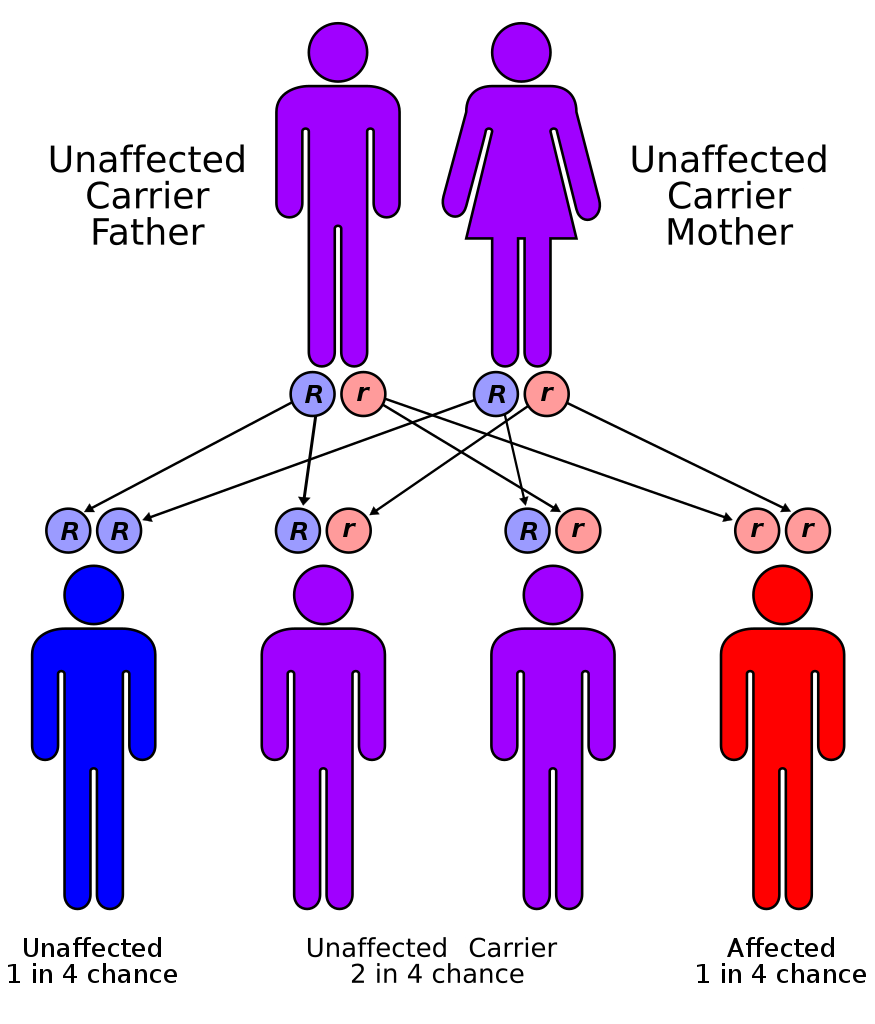

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder that affects many parts of the body, but its most devastating effects are on the lungs. The disease is an autosomal recessive gene, so a child of two carrier parents (they do not actually have, or express, the disease) has a 25% chance of actually being affected by CF, a 50% chance of being a carrier, and a 25% chance of being completely free of the gene.

Long Description

Autorecessive

Illustration with human stick figures labelled and connected by arrows. 2 parents are shown: an unaffected carrier father and mother. Below each is a blue R and a red R. Below the parents are 4 children. Child 1 is labelled “Unaffected, 1 in 4 chance” and has 2 blue R’s, 1 from dad and 1 from mom. Child 2 is labelled “Unaffected carrier: 2 in 4 chance” and has 1 blue R from dad and 1 red r from mom. Child 3 is also labelled “Unaffected carrier: 2 in 4 chance” and has has 1 blue R from mom and 1 red r from dad. Child 4 is labelled “Affected: 1 in 4 chance” and has 2 red R’s, 1 from dad and 1 from mom.

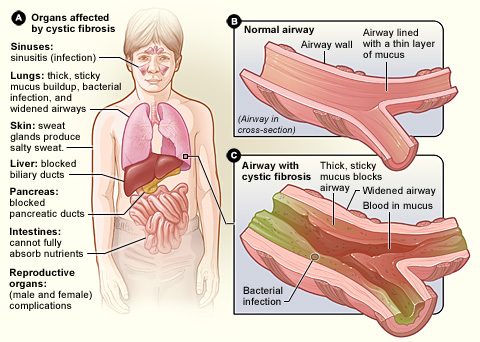

People with CF have abnormalities with their lungs, pancreas, kidneys, liver, and intestines. Almost all males with CF are sterile. The problem is with a protein involved with the creation of sweat and mucous throughout the body. The sweat and skin are very salty and the mucous is very thick in people with CF. The thick mucus affects the pulmonary, digestive, renal, and reproductive systems. The most profound symptoms are generally associated with lung function: respiratory infections, coughing up mucous, barrel chest, clubbing of the fingers and toes, difficulty breathing, wheezing, and in later stages, right-sided heart failure.

Long Description

Cystic fibrosis

Illustration with 3 sections – A: Organs affected by cystic fibrosis. B: Normal airway. C: Airway with cystic fibrosis.

- A: Organs affected by cystic fibrosis

- Sinuses: sinusitis (infection) infection, and widened airways

- Skin: sweat glands produce salty sweat.

- Liver blocked biliary ducts

- Pancreas: blocked pancreatic ducts

- Intestines: cannot fully absorb nutrients

- Reproductive organs:

- (male and female) complications

- B: Normal airway

- (Airway in cross section)

- Airway wall

- Airway lined with a thin layer of mucus

- C: Airway with cystic fibrosis

- Bacterial infection

- Thick, sticky mucus blocks airway

- Widened airway , blood in mucus

The disorder is often diagnosed in infancy or early childhood. There is no cure for the disease, but it can be managed. The life expectancy for a person with CF is now 40-50 years, which marks a huge improvement in the past 30 years. The disorder can be managed through various medications and procedures, which focus on improving the quality of life for most patients.

Since the thick, sticky mucous in the lungs is such a rich environment for bacterial infection, patients take antibiotics almost all the time. Health care workers need to be very careful regarding transmission of bacteria and other organisms to and from CF patients. Medications to thin mucus secretions, replace pancreatic enzymes, reduce inflammation, and assist with breathing are also employed. Chest physical therapy is useful in providing percussion, postural drainage, vibration, breathing and assisted coughing techniques, and ventilatory muscle training. Other areas of PT that should be included are postural training, mobilization of the thorax, and breathing exercises. General cardiovascular conditioning is also helpful. There are several devices that can provide mechanical assistance in moving the mucus into larger airways. These include autogenic drainage devices, such as positive expiratory pressure (PEP) devices or Flutter valve therapy devices, and mechanical percussion devices. Patients with CF need to use these devices and/or manual methods for moving secretions in the lungs several times each day.

As the disease progresses and lung function diminishes, some patients are the recipients of lung or heart-lung transplantations, which can extend life. Gene therapy is in the experimental stages and shows promise as an effective cure for this disease.

For some really cool research going on to help people with CF, read this short article.

Watch the video on cystic fibrosis.

5.6 – Resource 17 – What is Cystic Fibrosis? – Khan Academy

5.6.5.3 Lung cancer

The lung can be a primary site for cancer, or a secondary site for cancers that have metastasized. The strongest risk factor for primary lung cancer is smoking. Other risk factors include genetic factors, exposure to asbestos, coal dust, air pollution, or radon gas. Genetic factors also play a role; 10-15% of lung cancers occur in individuals who have never smoked.

In lung cancer, the epithelial cells lining the lungs are damaged and undergo many generations of mutations. In the mutations, DNA can be damaged, creating abnormal cancer cells that proliferate and grow without control. From the lung, tumors can metastasize and colonize in any part of the body. One reason lung cancer remains the deadliest cancer in the US for both men and women is that lung cancer tends to grow and metastasize very quickly. The tumors in the lungs take up space normally occupied by functioning lung parenchyma, and they can obstruct air passageways in the lung. Symptoms include dyspnea, wheezing, coughing, hemoptysis, chest pain, weight loss, fever, clubbing of the fingernails, and fatigue.

X-rays, CT scans, MRIs, tissue biopsies, and sputum sample testing are used to diagnose lung cancer. Treatment for this condition includes chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgical resection of part of or of an entire lung.

Think about this….

- Why would a patient who is having difficulty breathing lean forward and support themselves with their arms on a walker or countertop? Why would this position help them to breath more easily?

- One recommendation PTAs can make for patients who have pulmonary difficulties, particularly COPD, is to employ pursed-lip breathing. In this breathing pattern, the patient purses their lips on expiration. Why is this helpful?

- If a patient experiences long-standing pulmonary dysfunction, are they more likely to have associated right-sided or left-sided heart failure? Why?

- A patient who is hyperventilating is more likely to experience:

- Respiratory alkalosis

- Respiratory acidosis

5.7 Medications Commonly Used to Manage or Treat Pulmonary Conditions

Bronchodilators, inhaled: most often used to treat asthma and COPD; can be used in other conditions that obstruct the pulmonary system

Short-acting beta-2-adrenergic agonists: quickly decrease bronchial constriction and open airways in the case of asthma attack or respiratory distress due to obstructed breathing, as in COPD or CF; can be used 20 minutes before an exercise session to prevent an asthma attack (example: salbutamol)

Long-acting beta-2-adrenergic agonists: act to maintain open airways and prevent bronchoconstriction; used mainly for asthma (examples: salmeterol, salbutermol (albuterol), and formoterol, corticosteroids)

Anticholinergics: used to improve lung function and prevent exacerbations; used for asthma and COPD (examples: tiotropium (Spiriva) and ipratropium bromide)

Side effects of bronchodilators: dry mouth, tremor, headache, palpitations, muscle cramps, coughing, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea)

Antibiotics: used to treat pulmonary bacterial infections, such as pneumonia or infections associated with CF (examples: Levofloxacin (Levaquin), Clindamycin (Cleocin), Piperacillin-tazobactam (Zosyn)

Side effects of antibiotics: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, increased sun sensitivity, yeast infections

Antivirals: used to treat pulmonary viral infections, such as pneumonia (examples: oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), or peramivir (Rapivab))

Side effects of antivirals: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache

Antifungals; used to treat pulmonary lung infections, especially fungal pneumonias, including histoplasmosis; (examples: amphotericin B, amphotericin, itraconazole)

Side-effects of antifungals: can cause life-threatening allergic reactions

Expectorants (Mucus-thinning drugs): these drugs thin the mucus and lubricate the airway; assists patients to mobilize secretions out of airways where they obstruct airflow; (example: guaifenesin/hydrocodone)

Side effects of expectorants: headache, dizziness, sedation, nausea, diarrhea, decreased blood pressure

Flu and pneumonia vaccines are very important preventative measures for people with chronic pulmonary conditions. They are also important for anyone in an immunocompromised state, including autoimmune disease or other chronic condition, in chemo- or radiation therapy, elderly, or affected by other cormorbitidies, such as diabetes, heart failure, kidney disease, or liver disease. Flu and pneumonia vaccines can help prevent dangerous pulmonary infections from occurring in those at risk.

5.8 Pulmonary Conditions and the PTA

Many patients seen in physical therapy will be affected by some sort of pulmonary condition. Asthma is very common, and attacks are often triggered by exercise. Many patients will have had recent surgery and are at risk for pneumonia and pulmonary emboli. Smoking and exposure to asbestos, coal or air pollution are common risk factors, as well. The PTA needs to have a working knowledge of the pulmonary system and conditions. Patient education regarding smoking cessation and avoidance of substances or situations that put patients at risk for pulmonary conditions needs to be addressed in physical therapy sessions. The PTA needs to be vigilant regarding signs of respiratory difficulties and needs to be able to react quickly and appropriately if signs become evident. Familiarity with and confidence in taking vital signs are extremely important for the PTA.

Here are a few questions for a quick review:

The Pulmonary System Resources

Section 5.0

Resource 01 – The Respiratory Complete System

Resource 02 – “The lungs and pulmonary system | Health & Medicine | Khan Academy” by Khan Academy is licensed under Fair Use

Section 5.1

Resource 01 – The Mechanisms of Breathing

Section 5.2

Resource 01 – Breathing and Lung Capacities

Section 5.3

Resource 01 – Normal Respiratory Rates (bpm) for various ages

Section 5.4

Resource 01 – Chest Excursion /Expansion

Resource 02 – Clubbing Fingers or Acopaquia

Resource 03 – – Clubbing illustration

Section 5.5

Resource 01 – Chest Excursion/Expansion

Resource 02 – Alternate Measure for Chest Excursion

Resource 03 – Pigeon chest/pigeon breast/pectus carinatum

Resource 04 – Pectus excavatum (Funnel chest)

Resource 05 – Spirometry (Incentive inspiratory spirometry)

Resource 06 – Spirometry (Incentive inspiratory spirometry)

Resource 07 – Pulse oximeter

Section 5.6

Resource 01 – Pneumothorax

Resource 02 – Atelectasis

Resource 03 – Pleural Effusion

Resource 04 – Bronchiectasis

Resource 05 – Tuberculosis

Resource 06 – Primary and Secondary TB – Khan Academy

Resource 07 – Chronic Bronchitis – Khan Academy

Resource 08 – What is Emphysema? – Khan Academy

Resource 09 – Gross Pathology of lung showing centrilobular emphysema characteristics of smoking

Resource 11 – Asthma

Resource 12 – Asthma

Resource 13 – What is Asthma? – Khan Academy

Resource 14 – Asthma pathoshysiology – Khan Academy

Resource 15 – Cystic Fibrosis

Resource 16 – Cystic Fibrosis

Resource 17 – What is Cystic Fibrosis? – Khan Academy

Resource 18 – Lung Cancer

Section 5.7

Section 5.8