Chapter 7: The Hematological and Lymphatic Systems

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the learner should be able to:

- Define the basic terminology associated with blood and lymphatic disorders.

- Discuss signs and symptoms of blood and lymphatic disorders.

- Discuss basic medical diagnosis of blood and lymphatic disorders.

- Relate abnormal blood values to selected disorders.

- Discuss risk factors, etiologic factors, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations for the following blood and lymphatic conditions:

- Red Blood Cell Disorders

- (1) Anemia

- (2) Polycythemia

- White Blood Cell Disorders

- (1) Leukopenia

- (2) Leukocytosis

- (3) Leukemia

- Platelet Disorders

- (1) Thrombocytosis

- (2) Thrombocytopenia

- Clotting Factor Disorders: Hemophilia

- Lymphatic Disorders

- (1) Lymphedema

- (2) Lymphoma

- Red Blood Cell Disorders

- Describe medical, surgical and physical therapy interventions associated with blood and lymphatic conditions.

- Describe the pharmacological management of blood and lymphatic conditions.

- Discuss precautions, indications and contraindications to be considered in physical therapy interventions for patients with blood and lymphatic conditions.

Chapter Contents

For a good review of the different types of blood cells and a few hematologic disorders, watch the following video:

Diagnostic tools

The main diagnostic tool for hematologic disorders is a complete blood count, which is determined by drawing a sample of blood from a vein and viewing the different cells under a microscope. The cells are evaluated for number, sizes and shapes. Red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma cells are assessed in a CBC, or complete blood count. Clotting time tests and clotting assays are performed to determine the presence or absence of clotting factor.

The following are normal complete blood count results for adults:

| Category | Male and Female Amounts |

| Red blood cell count | Male: 4.35-5.65 trillion cells/L* (4.32-5.72 million cells/mcL**) Female: 3.92-5.13 trillion cells/L (3.90-5.03 million cells/mcL) |

| Hemoglobin | Male: 13.2-16.6 grams/dL*** (132-166 grams/L) Female: 11.6-15 grams/dL (116-150 grams/L) |

| Hematocrit | Male: 38.3-48.6 percent Female: 35.5-44.9 percent |

| White blood cell count | 3.4-9.6 billion cells/L (3,400 to 9,600 cells/mcL) |

| Platelet count | Male: 135-317 billion/L (135,000 to 317,000/mcL) Female: 157-371 billion/L (157,000-371,000/mcL) |

Other tools that are helpful to the PTA to determine the condition of the hematological system include: oxygen perfusion data, heart rate, blood pressure, respiration rate, and rate of perceived exertion.

Problems with Red Blood Cells

Anemia

Anemia is a condition caused by a decrease in the number of circulating erythrocytes or by a decrease in the functional abilities of the erythrocytes, namely diminished hemoglobin content or function. In either case, the oxygen delivery system, which is dependent upon the hemoglobin in the red blood cells (RBCs) is diminished and all areas of the body can be affected. In adults, normal hematocrit levels (measures the level of hemoglobin) is 14g/100ml in males and 12g/100ml in females. Any values below these are considered anemic. Anemia is often a sign of other conditions or diseases including:

- Dietary deficiency: most often an iron deficiency or generally decreased caloric intake; also decreased folic acid and Vit B12 intake can cause anemia

- Acute or chronic blood loss: from gastric ulcers (NSAID use can be the culprit), or from burns or trauma

- Chronic inflammatory disease, such as RA or SLE

- Infectious disease, such as TB or HIV/AIDS

- Neoplastic (cancerous) conditions that affect bone marrow and blood cell production

- Congenital defects in bone marrow or blood cell production (sickle cell anemia and thalassemia disorder are examples)

- Exposure to some industrial poisons, such as lead

- Hepatic or renal disease

Signs and symptoms of anemia are associated with lack of oxygen to different parts of the body, as listed below:

- Fatigue: heart, lungs and brain

- Confusion: brain

- Pallor: skin

- Brittle skin and nails

- Angina: heart

- Dyspnea and tachycardia: compensatory mechanisms to make up for lack of O2 in circulation

The treatment for anemia depends on the underlying cause. For nutritional deficiencies, supplemental iron, folic acid, and Vit B12 can be administered. If blood loss through gastric bleeding is the problem, NSAID use should be discontinued and possible Helicobactor pylori (H. pylori) bacteria infection should be investigated. Lead poisoning and other types of toxic exposures are treated by eliminating exposure to these elements. Other conditions associated with anemia, such as chronic disease, infections or diseases of the bone marrow, and hepatic and renal disease should be treated at the source, with possible dietary supplementation to help with the anemia. Bone marrow transplants and chemotherapy may be used in cancerous conditions and bone marrow disease. Blood transfusions are also useful in severe anemia.

The prognosis for relief from anemia is excellent in the case of nutritional etiology, as dietary supplements are generally available and effective. If the problem is with the bone marrow, congenital or cancerous condition, prognosis is generally less favorable, but varies with condition.

Thalassemia

Thalassemia is an inherited blood disorder in which hemoglobin is decreased and the number of RBCs is decreased, causing mild to severe anemia. There are several different genes involved in the development of thalassemia, and the condition varies in severity, depending upon the number of genes involved. In most cases, the condition can be managed through blood transfusions and medications. Signs and symptoms include:

- Fatigue

- Weakness

- Pale or yellowish skin

- Facial bone deformities

- Slow growth

- Abdominal swelling

- Dark urine

- Enlarged spleen

People with thalassemia disorder are at increased risk for infection and iron overload, which is detrimental to the heart, liver and endocrine system.

In cases of severe thalassemia, the following complications can occur:

- Bone deformities.Thalassemia can make your bone marrow expand, which causes your bones to widen. This can result in abnormal bone structure, especially in your face and skull. Bone marrow expansion also makes bones thin and brittle, increasing the chance of broken bones.

- Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly).The spleen helps your body fight infection and filter unwanted material, such as old or damaged blood cells. Thalassemia is often accompanied by the destruction of a large number of red blood cells. This causes your spleen to enlarge and work harder than normal. Splenomegaly can make anemia worse, and it can reduce the life of transfused red blood cells. If your spleen grows too big, your doctor may suggest surgery to remove it (splenectomy).

- Slowed growth rates.Anemia can cause a child’s growth to slow. And thalassemia may cause a delay in puberty.

- Heart problems.Heart problems — such as congestive heart failure and abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias) — may be associated with severe thalassemia.

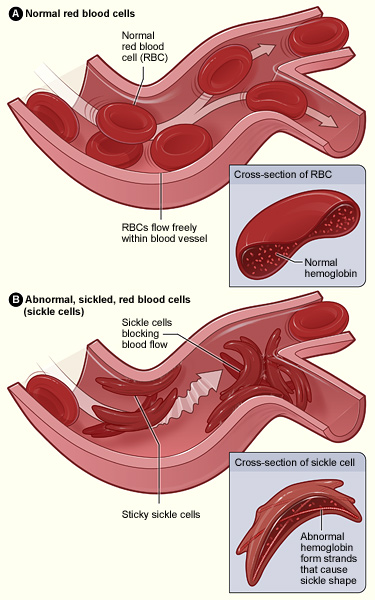

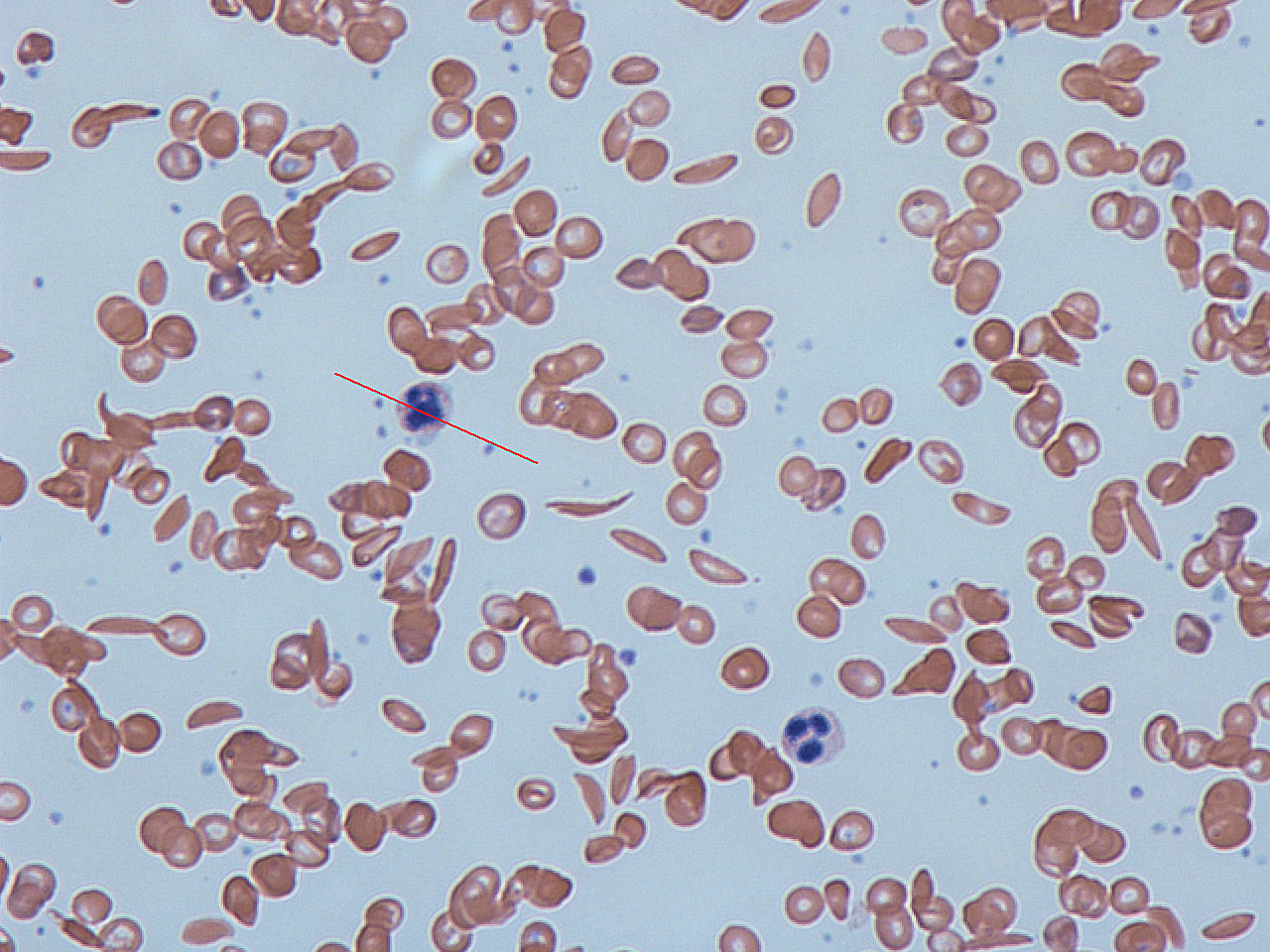

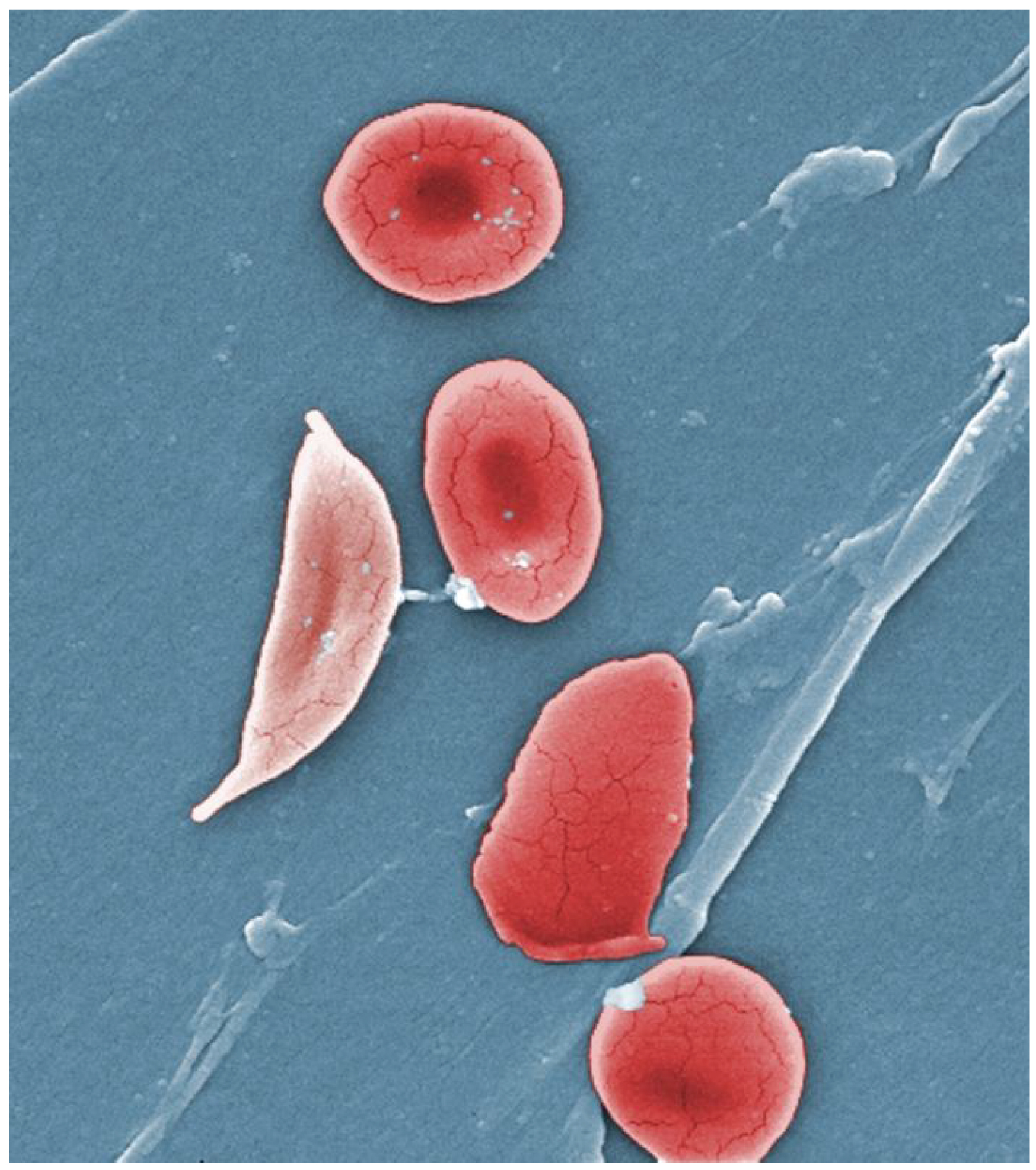

Sickle Cell Disease

The sickle cell trait is a recessive trait, found most commonly in people with origins in Africa, Hispanic cultures, the Middle East, the Mediterranean area, and India. Since it is a recessive trait, both parents must carry the gene for the offspring to develop the disease. One in 13 black or African American babies born in the US carry the sickle cell trait. One in 365 black or African American babies born in the US has sickle cell disease. (NIH: NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) In sickle cell disease, sometimes called sickle cell anemia, abnormal hemoglobin is formed, which causes the shape of the RBCs to be altered. Instead of soft, round doughnut forms, the RBCs are stiff and sickle-shaped. They are not able to carry oxygen to cells, so a state of anemia occurs. Their abnormal shape also allows for increased clotting of blood and more difficulty moving blood through the circulatory system. The abnormal RBCs also experience a shortened lifespan. Normally, RBCs remain in circulation for approximately 3 months, in sickle cell disease, the time is decreased to 20 days.

Early signs and symptoms of sickle cell disease include jaundice, fatigue, and painful swelling of the hands and feet, known as dactylitis.

Complications of sickle cell disease include:

- Acute chest syndrome: Sickling in blood vessels of the lungs can deprive a person’s lungs of oxygen. When this happens, areas of lung tissue are damaged and cannot exchange oxygen properly. This condition is known as acute chest syndrome. In acute chest syndrome, at least one segment of the lung is damaged. This condition is very serious and should be treated right away at a hospital. Acute chest syndrome often starts a few days after a painful crisis begins. A lung infection may accompany acute chest syndrome.

- Acute pain crisis, also known as sickle cell or vaso-occlusive crisis. Acute pain crisis can occur without warning when sickle cells block blood flow and decrease oxygen delivery. People describe this pain as sharp, intense, stabbing, or throbbing. Severe crises can be even more uncomfortable than postsurgical pain or childbirth. Pain can strike almost anywhere in the body and in more than one spot at a time. Common areas affected by pain include the abdomen, chest, lower back, or arms and legs. A crisis can be brought on by high altitudes, dehydration, illness, stress, or temperature changes. Often a person does not know what triggers, or causes, the crisis.

- Brain complications, such as a clinical or silent stroke: In sickle cell disease, a clinical strokemeans that a person shows signs of a stroke. However, children and adults who have hemoglobin SS and hemoglobin Sβ0 thalassemia often have signs of silent brain injury, also called silent stroke. Silent brain injury is damage to the brain without showing outward signs of stroke. This injury is common and can be detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Silent brain injury can lead to difficulty in learning, making decisions, or holding down a job.

- Chronic pain: Many adolescents and adults who have sickle cell disease experience chronic pain. This kind of pain has been hard for people to describe, but it is usually different from crisis pain or the pain that results from organ damage.

- Delayed growth and puberty: Children who have sickle cell disease may grow and develop more slowly than their peers because of anemia. They will reach full sexual maturity, but this may be delayed.

- Eye problems: Sickle cell disease can injure blood vessels in the eye. The most common site of damage is the retina, where blood vessels can overgrow, get blocked, or bleed. The retina is the light-sensitive layer of tissue that lines the inside of the eye and sends visual messages through the optic nerve to the brain. Detachment of the retina can occur. When the retina detaches, it is lifted or pulled from its normal position. These problems can cause visual impairment or loss.

- Gallstones: When red cells undergo hemolysis, they release hemoglobin. Hemoglobin gets broken down into a substance called bilirubin. Bilirubin can form stones that get stuck in the gallbladder. The gallbladder is a small sac-shaped organ beneath the liver that helps with digestion. Gallstones are a common problem in sickle cell disease.

- Heart problems, including ischemic heart disease and pulmonary hypertension. People who have sickle cell disease who have received frequent blood transfusionsmay also have heart damage from iron overload.

- Infections:The spleen is important for protection against certain kinds of infections. People who have sickle cell disease and damaged spleens are at risk for certain kinds of infections, including chlamydia, haemophilus influenzae type B, salmonella, and staphylococcus.

- Joint complications: Sickling in the hip bones and, less commonly, the shoulder joints, knees, and ankles can decrease oxygen flow and result in a condition called avascular or aseptic necrosis, which severely damages the joints. Symptoms include pain and problems with walking and joint movement. A person may need pain medicines, surgery, or joint replacement if symptoms persist.

- Kidney problems: The kidneys are sensitive to the effects of red blood cell sickling. Sickle cell disease causes the kidneys to have trouble making the urine as concentrated as it should be. This may lead to a need to urinate often and to bedwetting or uncontrolled urination during the night. This often starts in childhood.

- Leg ulcers: Sickle cell ulcers are sores that usually start small and then get larger and larger. Some ulcers will heal quickly, but others may not heal and may last for long periods of time. Some ulcers come back after healing. People who have sickle cell disease usually do not get ulcers until after age 10.

- Liver complications: Sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis is an uncommon but severe type of liver damage that occurs when sickled red cells block blood vessels in the liver. This blockage prevents enough oxygen from reaching liver tissue. These episodes are usually sudden and may recur. Children often recover, but some adults may have chronic problems that lead to liver failure. People who have sickle cell disease who have received frequent blood transfusions may develop liver damage from iron overload.

- Pregnancy complications: Pregnancies in women who have sickle cell disease can increase the risk for high blood pressure and blood clots in the mother. Sickle cell disease also increases the risk for miscarriage, premature birth, and low birth weight babies.

- Priapism, which is an unwanted, sometimes prolonged, painful erection. Priapism happens when blood flow out of the erect penis is blocked by sickled cells. Over time, priapism can cause permanent damage to the penis and lead to impotence. Priapism that lasts for more than 4 hours is a medical emergency.

NIH: NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute)

Treatment for sickle cell disease includes: oxygen administration, fluid replacement, pain medications, blood transfusions, antibiotics, and bone marrow transplant. Hydroxyurea is a medication also prescribed to limit the number of sickle cell crises and painful chest episodes.

For a quick tutorial on sickle cell disease, check out this video.

Polycythemia

If the red blood cells are too plentiful, a condition known as polycythemia exists. Elevated erythrocyte counts can be a primary or secondary condition, but in either case, the excess of red blood cells causes the blood to be thicker than normal and more likely clot. When the blood is thick, it flows more slowly, and many areas of the body can suffer from oxygen deficiency. Some conditions associated with PV include:

- Bluish-red skin and mucosa

- Dizziness, blurred vision, fainting

- Headache

- Hypertension

- Splenic and hepatic enlargement

- Itchiness

- Thrombus formation

- Heart failure

- Stroke

- Peripheral vascular disease

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a primary polycythemia that is caused by an abnormal mutation in a gene that is responsible for turning off RBC production in the bone marrow. PV is a rare condition that can be managed, but not cured. People with PV manage their condition with periodic blood letting (removal of blood, as is done in blood donation), anticoagulating drugs, such as aspirin, heparin, or coumadin, and chemotherapy to kill hyperplastic cells in the bone marrow.

Secondary polycythemia occurs when the amount of oxygen available to cells is diminished, and the body compensates by producing more red blood cells. People who have had a stroke or heart attack are at risk for secondary polycythemia because of the oxygen deprivation experienced in the brain and heart. Even living at high altitudes, where the oxygen content of air is less than at sea level, can cause secondary polycythemia. In the case of secondary polycythemia, the condition is treated by correcting the primary causative factor.

Mayo Clinic: Polycythemia vera

Problems with White Blood Cells

Leukopenia

There are many different categories of white blood cells (WBCs), or leukocytes, in circulation. Monocytes, neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils can be affected in leukopenia. If there are too few of any or all of these leukocytes, the condition is termed leukopenia. Since one of the major functions of the white blood cells is to fight infection, people with decreased cell counts of WBCs are at risk for infection. Many conditions can cause a state of leukopenia, including HIV/AIDS, alcoholism, nutritional deficiencies, lupus erythematosus, bone marrow abnormalities and malignancies, Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, tuberculosis, and splenic abnormalities. Radiation therapy and drug therapies including chemotherapy and steroid therapy can also cause leukopenia.

The symptoms of leukopenia are those of infection: fever, sore throat, respiratory conditions, ulcerations. These infections occur frequently and are often long-lasting. It is very important for people with low white blood cell count avoid exposure to infectious agents and take precautions such as flu and pneumonia vaccinations.

Leukocytosis

If a higher than normal count of white blood cells in circulation exists, the result in a condition known as leukocytosis. Leukocytosis is most often a response to acute or chronic infection. Bone tumors and leukemia can also cause leukocytosis. Some medications, such as corticosteroids, can cause leukocytosis. There is no specific treatment for leukocytosis, but the underlying cause needs to be addressed.

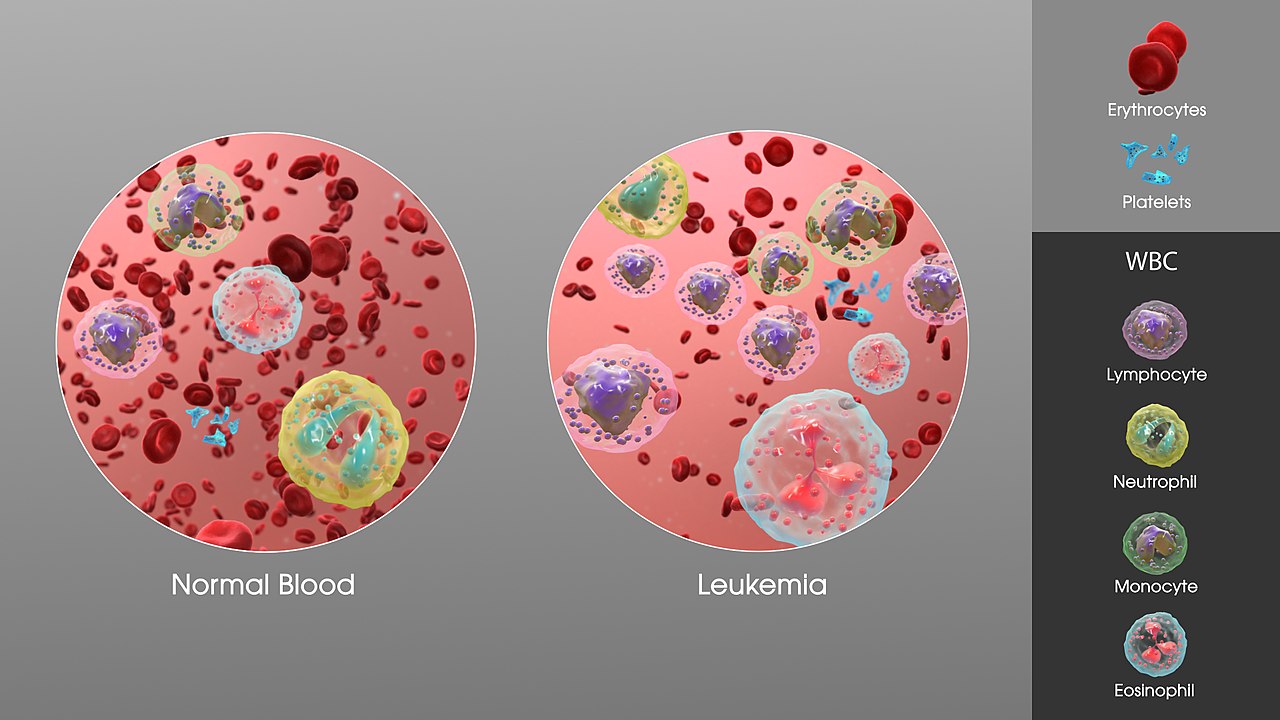

Leukemia

There are many different types of leukemia, but all involve mutations that occur during the production of WBCs in the bone marrow. An overproduction of immature WBC precursor cells “crowd out” normal blood cells in the bone marrow and in the circulating blood, leading to anemia, infection, bleeding and bruising, as the normal counts of mature RBCs, WBCs, and thrombocytes are diminished by the immature “blast” cells found in leukemia.

The major subdivisions of leukemia are acute and chronic, and lymphocytic and myelogenous.

Four major kinds of leukemia

| Cell type | Acute | Chronic |

|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytic leukemia (or “lymphoblastic”) |

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) |

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) |

| Myelogenous leukemia (“myeloid” or “nonlymphocytic”) |

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML or myeloblastic) |

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) |

Each of these divisions includes several specific types of leukemia, depending upon the etiology which causes certain markers to appear on the involved cells. It is important to determine which type of leukemia is present in order to provide the most appropriate medical intervention, but that level of specificity is beyond the scope of this book. An excellent description of the different types of acute leukemia is presented in the following video. The first several minutes of the video provide general information that is important for PTAs to know. The diagnostic markers and genetic basis of the different types of leukemia are less important for PTAs.

Chronic leukemias are explained in the following video link. This video gets pretty specific pretty quickly. Watch for general information only.

Etiology of Leukemia

Leukemia results for abnormal mutations in the DNA that occurs in the production of blood cells. Exactly why this happens is largely unknown. In adults, the development of leukemia has been linked to exposure to ionizing radiation, some viruses (human T-lymphotropic virus) and some chemicals, including some drugs used in chemotherapy. There appears to be a genetic component, as family members who share genetic material with someone with leukemia are at a higher-than-average risk for the development of leukemia. People with Down syndrome develop leukemia more often than people with out Down syndrome.

Signs and symptoms of leukemia

The signs and symptoms of leukemia are related to the pathophysiology. Bone pain can occur due to the excess blood cell production activity in the bone marrow. Because of the relative loss of normal red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets in the blood, oxygenation of tissues is diminished, causing fatigue and weakness, and bleeding and bruising under the skin occur. The lack of circulating leukocytes causes an increased risk for infection. The spleen, liver, and lymph nodes become enlarged because of the extra workload of handling the abnormal cells in the blood.

Long Description

Common Symptoms of Leukemia

- Systemic

- Weight loss

- Fever

- Frequent infections

- Lungs

- Easy shortness of breath

- Muscular

- Weakness

- Bones or joints

- Pain or tenderness

- Psychological

- Fatigue

- Loss of appetite

- Lymph nodes

- Swelling

- Spleen and/or liver

- Enlargement

- Skin

- Night sweats

- Easy bleeding and bruising

- Purplish patches or spots

Treatment for Leukemia

Leukemia can be treated, and in many cases cured, through pharmaceutical medication. Radiation and bone marrow transplants are also used in some cases. Treatment is aimed at suppressing the bone marrow production of blast cells and keeping organs free from effects of the condition. Steroidal medications, immunosuppressive medications, and disease modifying medications are all used in the treatment of leukemia. Some forms of leukemia are much more responsive to chemotherapy than are others, so the cure rate varies with the type of leukemia. Patients who are undergoing treatment for leukemia are at increased risk for infection, so it is important that PTAs and other health care providers are extremely careful about hand hygiene and other deterrents to disease transmission when working with this patient population.

Problems with Platelets

Thrombocytopenia

The thrombocytes, or platelets, in the blood stream help blood to clot by clumping together. They cause bleeding to stop by providing a physical barrier to blood leaving the blood vessels. If there are too few platelets, bleeding can go on unchecked and even small openings in blood vessels can allow large amounts of blood to escape. This condition is caused by a genetic disorder or is associated with other conditions, such as leukemia, nutritional deficit, systemic infection, liver failure, or autoimmune condition.

Thrombocytes, or platelets, are responsible for stopping the flow of blood by clotting and providing a physical barrier to blood escaping blood vessels. A normal platelet count ranges from 150,000 to 450,000 platelets per microliter of blood (NIH). If the platelet count is low, the disorder is termed thrombocytopenia. This condition causes bleeding from the gums and mucosa, spontaneous nose bleeds, bleeding under the skin, and bleeding from any area of the body. Petachiae, pupura, and echymosis are commonly seen when the platelet counts are very low.

Thrombocytopenia can be caused by several different factors. There are many inheritable genetic disorders associated with thrombocytopenia. Nutritional deficit, dehydration, liver failure, sepsis or other infection, leukemia, alcoholism and some medications (blood thinners such as coumadin and heparin, methotrexate) can also cause a state of thrombocytopenia.

Treatment of Thrombocytopenia

Once thrombocytopenia is diagnosed through total blood count, treatment is administered in relation to the underlying cause of the condition. Any anti-coagulating medications, including aspirin and ibuprofen, should be eliminated from the patient’s drug regime. Attention should be paid to the risk of thrombus formation with the change in the medication usage. Antibiotics are used in the case of bacterial infection or sepsis. Nutritional supplements can be used, such as folic acid. Corticosteroids can be administered to help increase platelet formation. Idiopathic thrombocytopenia is often not treated with medication, as it will go into remission in most cases. Rarely, a patient will have a platelet count that is so low that they might need a transfusion of platelets.

A PTA working with a patient with thrombocytopenia should avoid placing the patient in any activity where injury could occur. Bleeding under the skin or into joints can occur with even minor trauma. Pressure from orthotic devices or prosthetics can cause small cutaneous blood vessels to break, so a PTA should carefully observe the skin and underlying tissue in patients who have thrombocytopenia.

Thrombocythemia and Thrombocytosis

When the number of platelets is high, the condition can be either thrombocythemia or thrombocytosis. Thrombocythemia is often called essential or primary thrombocythemia. This term is applied when the platelet count is high, and no other hematologic conditions are present or contributing to the condition. Thrombocytosis is the term most often applied to secondary conditions, so it is most often called secondary or reactive thrombocytosis.

In primary thrombocythemia, faulty stem cells in the bone marrow produce too many platelets, which are abnormal and do not function well in their role to produce a clot. There is no known cause or risk factor for this disorder, although some more rare forms are inherited.

In secondary thrombocytosis, there is another condition that is associated with the decreased platelet count. Cancer, splenectomy, anemia, inflammatory or infectious disease, and some medications are causative for secondary thrombocytosis. The platelets in secondary thrombocytosis are normal, they are just too many in number.

Signs and symptoms

Most people with thrombocythemia or thrombocytosis will have few or no signs and symptoms. When symptoms do develop, they can include: weakness, bleeding, headache, dizziness, chest pain, and tingling in the hands and feet. These effects are due to clots developing in small arterioles and capillaries. Bleeding can occur because the abnormal platelets found in primary thrombocytopenia are unable to effectively clot.

Treatment

For many people who have thrombocythemia or thrombocytosis, treatment is unnecessary because the condition stabilizes, and they suffer little or no consequences. Sometimes aspirin is prescribed to keep the blood from clotting too much. If the condition is secondary to another condition, the primary condition is addressed. Some people do need to take medications for life if they have a history of unwanted clotting, have other risk factors, or have an extremely high platelet count (> 1 million). Some mediations they could take include: hydroxyurea, aspirin, anagrelide, and interferon alpha. Plateletpheresis (removal of platelets from the blood) is used in emergencies, such as stroke.

Clotting Factor Disorders: Hemophilia

Hemophilia is a common bleeding disorder that is hereditary. It includes two main types, Type A and Type B, with Type A being the more common. Both types are X-lined recessive disorders, so they are carried by the mother and expressed in sons. Spontaneous genetic mutations rarely occur. Hemophilia is a lack of a clotting factor specific to the type of hemophilia. Acquired hemophilia can occur with cancers, autoimmune disorders, and pregnancy.

Without the clotting factor, even very small bleeds continue to bleed and can cause life-threatening blood loss. Bleeding can occur anywhere in the body. Common sites are nosebleeds, bleeding from the gums, bleeding into the joints, or sometimes, bleeding into the brain.

Signs and Symptoms

Bleeding may continue long after an injury in hemophilia. Bleeding under the skin, which shows up as bruising, is common, even with little pressure or minimal injury. If bleeding occurs in the joints, pain is felt, and the joints can be permanently damaged due to the excess blood on the bone surfaces. Bleeding into the brain can cause headaches, seizures, and strokes.

Treatment

Hemophilia is treated with infusions of the missing clotting factor. These prophylactic treatments prevent life-threatening blood loss in the case of injury. Most people with hemophilia are able to perform self-infusions and manage their condition independently. Some people develop antibodies, or inhibitors, that cause the clotting factors not to work. These people are at a high risk for continued bleeding episodes and long-term damage from bleeding into the joints or brain.

Lymphatic Disorders

Lymphedema

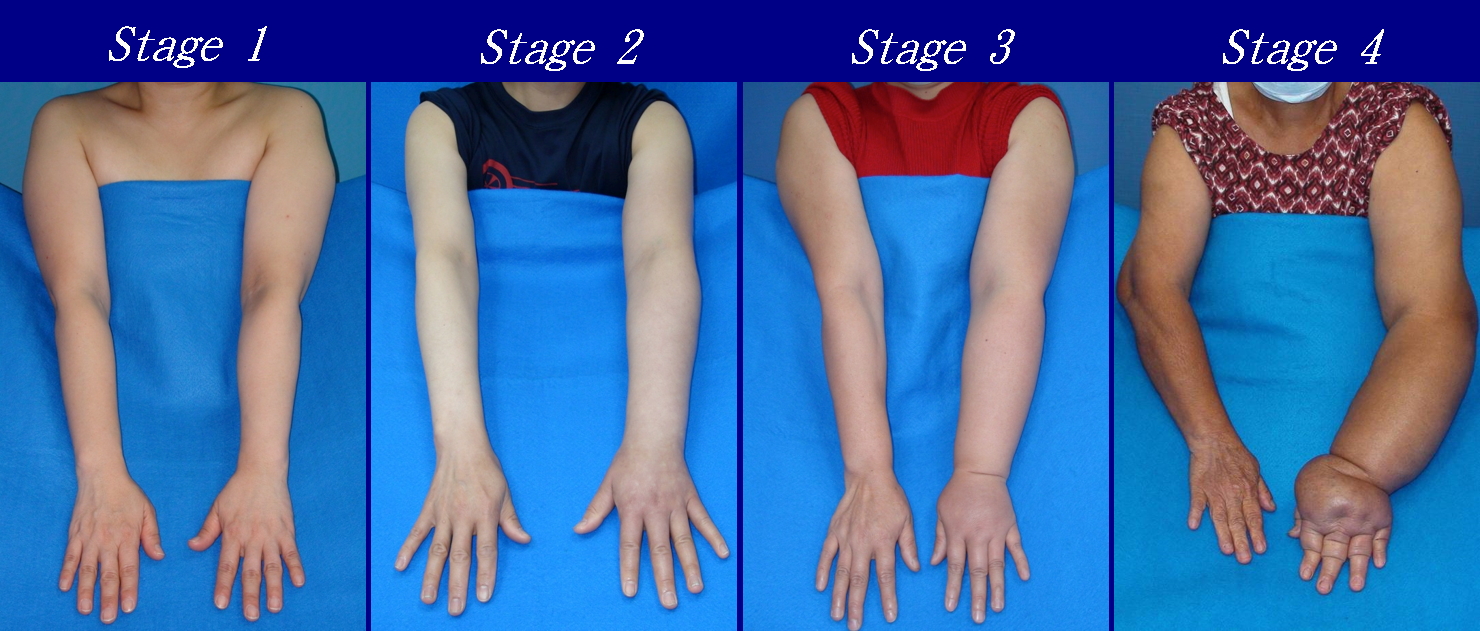

The lymphatic system is important for removal of extra fluid and waste products from the interstitial spaces in the body. It also plays an essential role in the storage and movement of lymphocytes (white blood cells), which help fight infection. If the lymphatic system is damaged lymph can accumulate in the trunk or extremities in a condition called lymphedema. Unlike other types of edema, lymphedema is an accumulation of lymphatic fluid, which is a protein-rich fluid. This fluid is more viscous that serous fluid associated with swelling in a mild injury, such as a sprained ankle. Lymphedema can be staged and can progress to a “woody” feel. The stages of lymphedema are listed below:

- Stage 0: The lymphatic vessels have sustained some damage that is not yet apparent. Transport capacity is sufficient for the amount of lymph being removed. Lymphedema is not present.

- Stage 1 : Swelling increases during the day and disappears overnight as the patient lies flat in bed. Tissue is still at the pitting stage: when pressed by the fingertips, the affected area indents and reverses with elevation. Usually upon waking in the morning, the limb or affected area is normal or almost normal in size. Treatment is not necessarily required at this point.

- Stage 2: Swelling is not reversible overnight, and does not disappear without proper management. The tissue now has a spongy consistency and is considered non-pitting: when pressed by the fingertips, the affected area bounces back without indentation. Fibrosis found in Stage 2 lymphedema marks the beginning of the hardening of the limbs and increasing size.

- Stage 3: Swelling is irreversible and usually the limb(s) or affected area become increasingly large. The tissue is hard (fibrotic) and unresponsive; some patients consider undergoing reconstructive surgery, called “debulking”. This remains controversial, however, since the risks may outweigh the benefits and the further damage done to the lymphatic system may in fact make the lymphedema worse.

- Stage 4: The size and circumference of the affected limb(s) become noticeably large. Bumps, lumps, or protusions (also called knobs) on the skin begin to appear.

- Stage 5: The affected limb(s) become grossly large; one or more deep skin folds is prevalent among patients in this stage.

- Stage 6: Knobs of small elongated or small rounded sizes cluster together, giving mossy-like shapes on the limb. Mobility of the patient becomes increasingly difficult.

- Stage 7: The patient becomes handicapped, and is unable to independently perform daily routine activities such as walking, bathing and cooking. Assistance from the family and health care system is needed.

Lymphedema is divided into two main categories: primary and secondary. Primary lymphedema is a congenital condition. Secondary lymphedema, or acquired lymphedema, occurs in association with another disorder, most often cancer with lymph node dissection.

The signs and symptoms of lymphedema include: increased limb girth, a feeling of heaviness, postural changes, and functional impairment of the affected limb. Patients often feel social-emotional isolation, as the appearance of the affected limb is noticeable to the public. Movement can be difficult for the patient, especially when the lower extremities are involved. Meticulous skin care is necessary in the case of lymphedema. The skin is subject to breakdown and the impaired immune system associated with lymphedema causes the body to have difficulty fighting infection.

Lymphedema is managed using manual lymphatic drainage (specialized massage), compression therapy, compression bandaging, compression garments, cardiovascular training, and ROM and strengthening exercises. Sequential pneumatic pumps and manual lymphatic drainage can be used to help push stagnant lymphatic fluid from the extremities into the larger lymphatic vessels in more proximal body areas. Low-stretch bandaging is used to provide the appropriate pressure to the underlying tissue and lymphatic structures, as high-stretch bandages (Ace bandages) are less effective because they compress superficial lymphatic vessels. Likewise, manual lymphatic drainage is a low-pressure massage technique designed to help lymphatic vessels open and receive more lymphatic fluid. Compressive garments are elasticized sleeves or stockings that are more easily applied than bandages. All the management therapy for lymphedema can be provided through physical therapy.

There is no known cure for lymphedema, but it is manageable for most patients. Surgeries are available for some patients with lymphedema. Surgeries involve re-routing the lymphatic flow, transplanting lymph nodes from one area of the body to another, or suction assisted lipectomy (SAL or liposuction).

Lymphoma

Lymphoma is cancer of the lymphatic system, specifically hyperplastic production of abnormal lymphocytes. All organs involved in the lymphatic system are affected by lymphoma, which is divided into 2 main categories: Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The diagnosis of lymphoma is performed through lymph node and fluid biopsy and blood tests.

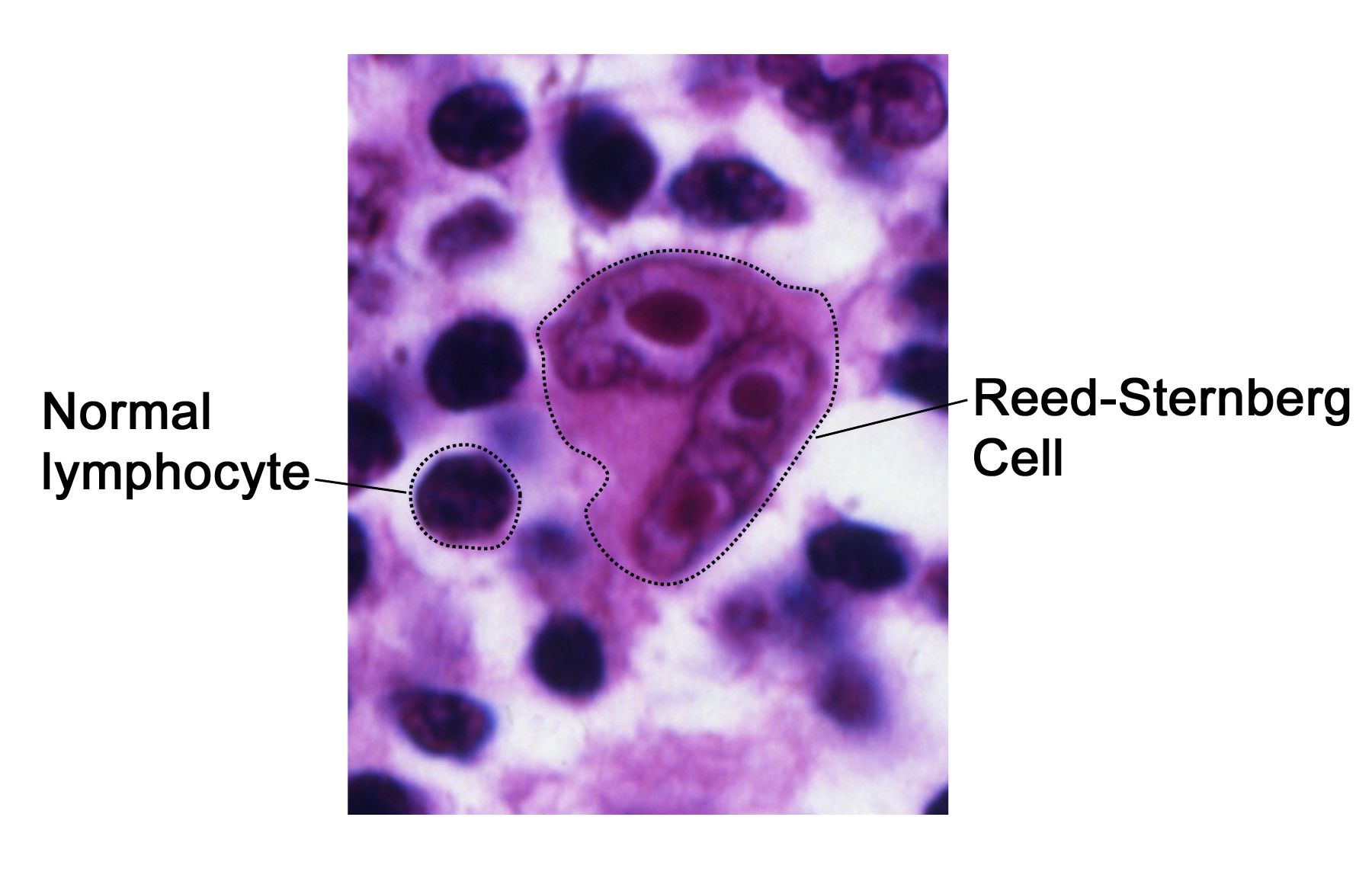

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) is diagnosed by microscopic visual inspection of fluid from a lymph node biopsy for the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells. These are large polynuclear lymphatic cells found only in Hodgkin lymphoma. Hodgkin lymphoma is more common in males and affects 2 age groups most often: 15-35-year-olds most often, with the over 55-year-olds second most often. Younger ages carry a more favorable diagnosis.

Infections by the Epstien-Barr virus, human T-cell lymphotrophic virus, and HIV are risk factors for the development of Hodgkin lymphoma. Other risk factors include a positive family history, and exposure to ionizing radiation.

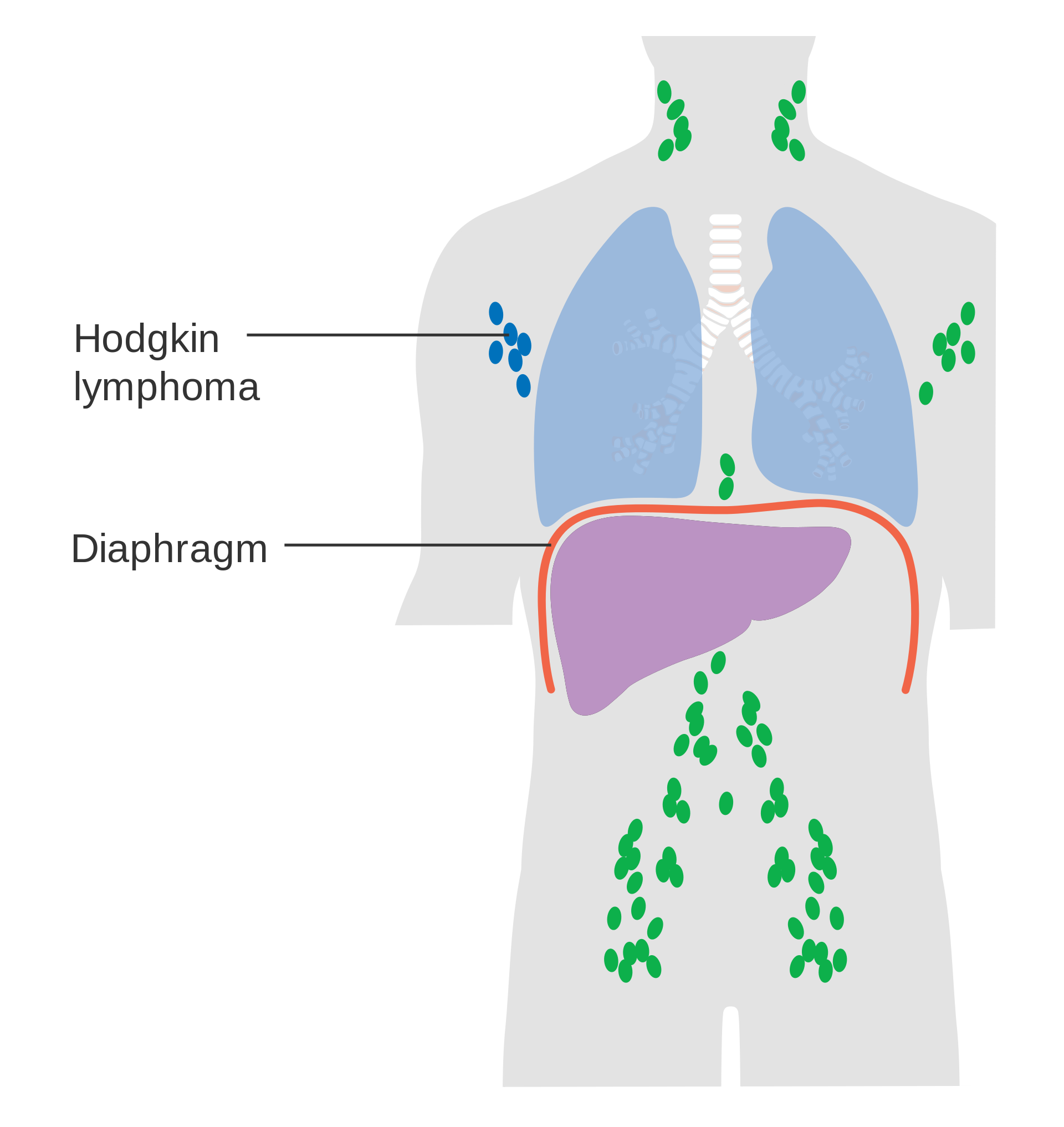

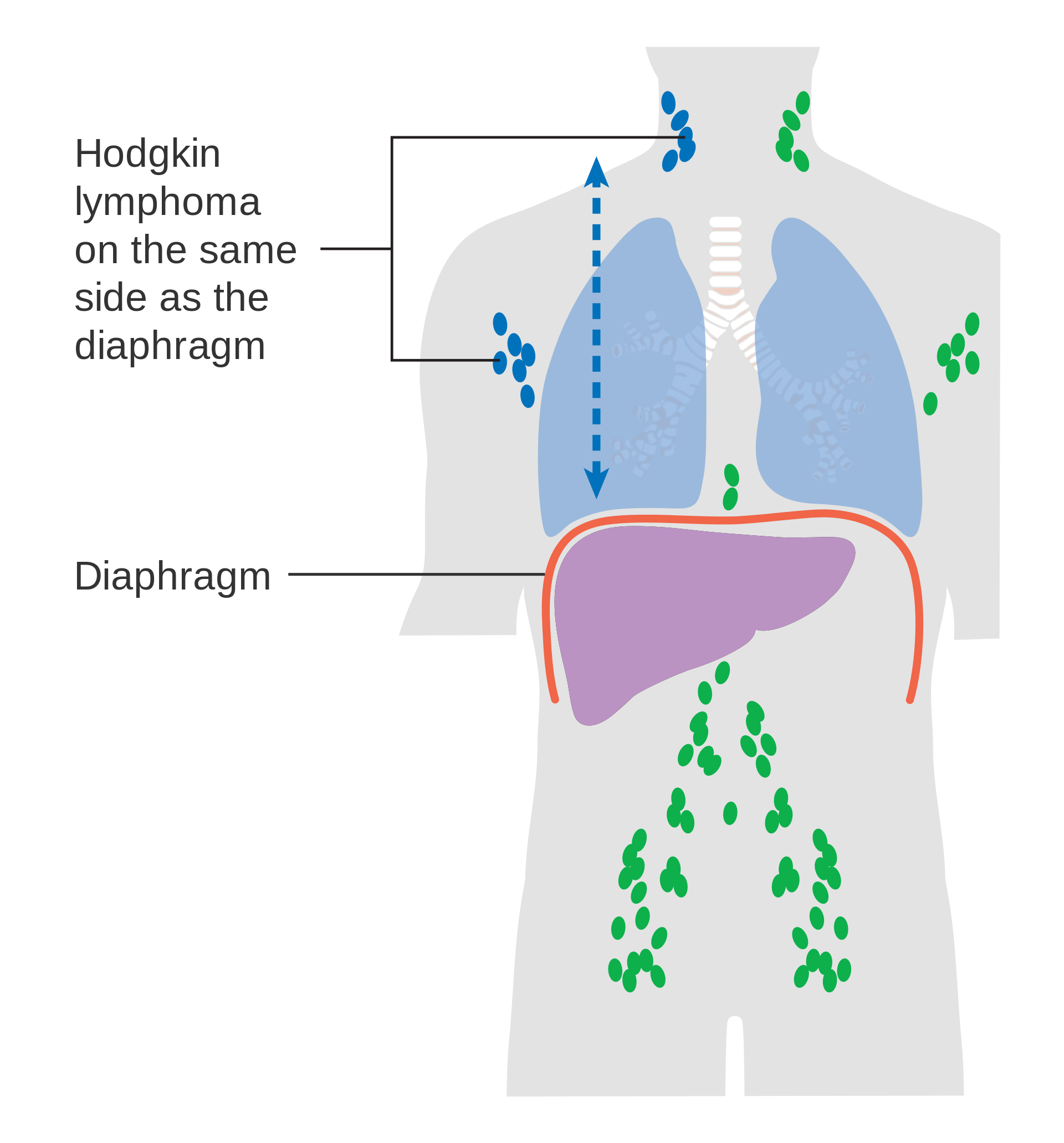

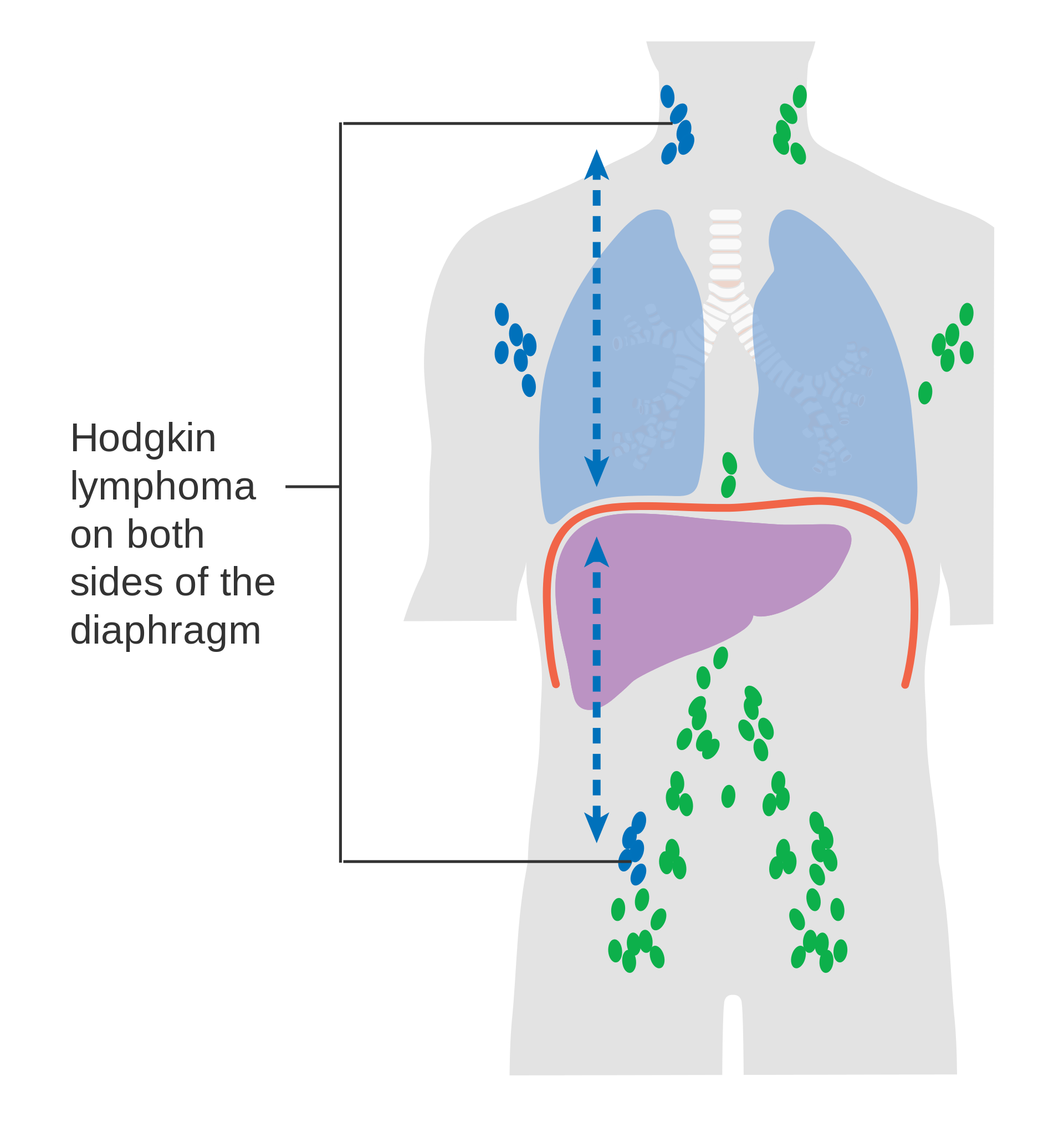

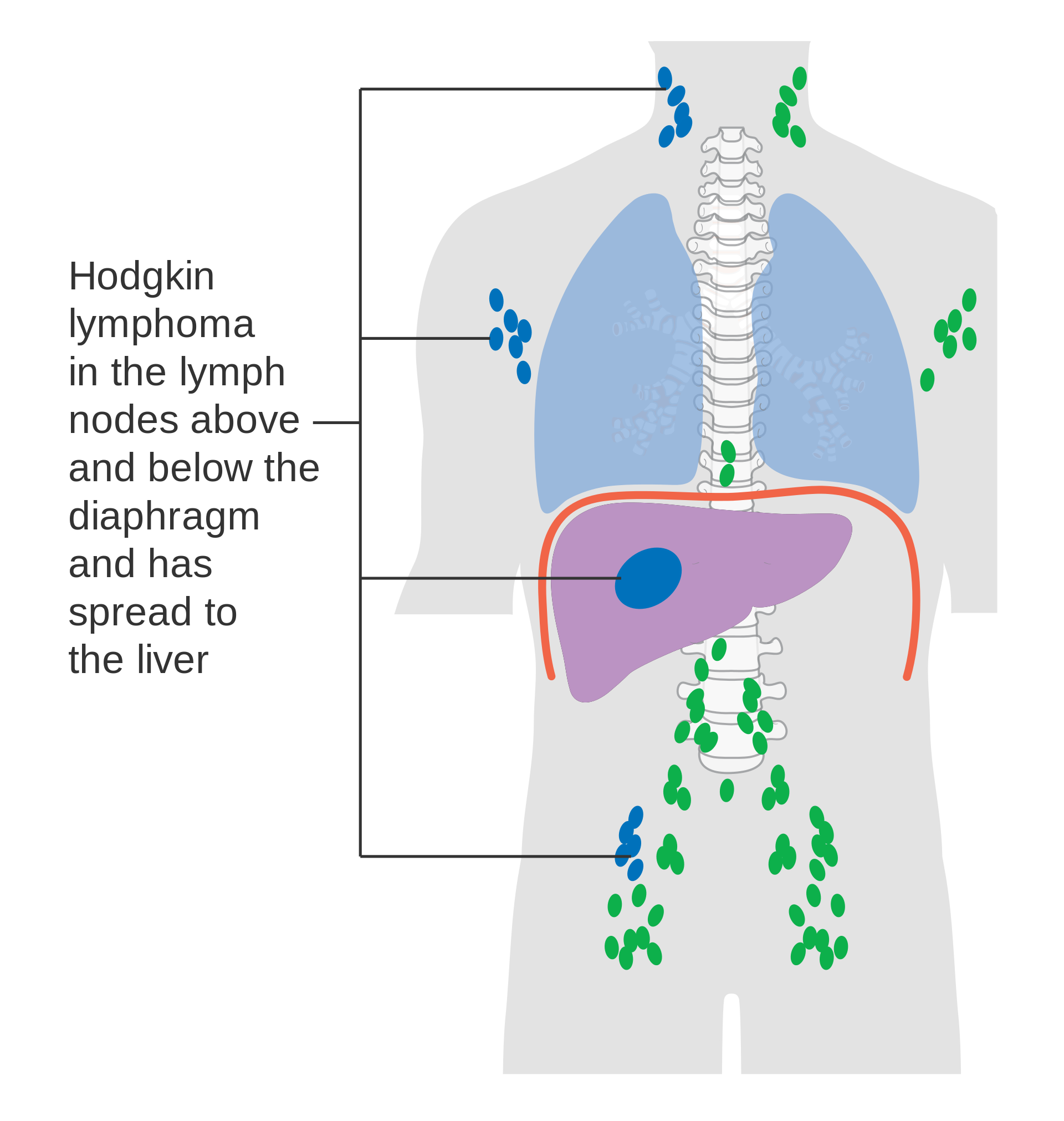

Hodgkin lymphoma begins in one area of the body and spreads in an orderly fashion throughout, so signs and symptoms appear as organs are involved. The signs and symptoms of Hodgkin lymphoma include: enlarged, painless lymph nodes, fever, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, itchy skin, and back pain.

There are subcategories of Hodgkin lymphoma and there are 4 stages of progression for the disease.

The treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma depends upon the subtype and stage of the disease process. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy are used with great success, especially in the early stages of the disease. The overall prognosis for Hodgkin lymphoma is relatively good, with almost all forms carrying a greater than 85% 5-year survival rate, and some forms nearly 100% 5-year survival rate. There are some concerns regarding long-term consequences of the radiation and chemotherapies used in managing Hodgkin lymphoma, namely leukemia, other forms of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and endocrine dysfunction.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Forms of cancer involved in lymphocyte production and lymphatic function that do no stain positively for Reed-Stemberg cells are categorized as non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or NHL. Either B-lymphocytes or T-lymphocytes are affected in NHL, and these two main categories are used to determine medical interventions for the disorders. The other level of categorization involved the speed of spread of the disease, and these categories are indolent or aggressive. There are some forms of NHL that do not fit into these categories, but most do. NHL affects older adults (over 60 years-old) more commonly than young adults and children. Other risk factors include: male gender, positive family history, weakened immune system (autoimmune disease, organ transplant), exposure to radiation, exposure to certain viruses (HTML-1, human papilloma virus, EBV), race, ethnicity, and geography (more common in wealthier nations, more common in Caucasians), chronic infections, and exposure to some chemicals, including drugs.

Signs and symptoms of NHL include: painless, swollen lymph nodes, abdominal pain or swelling, chest pain, coughing, trouble breathing, persistent fatigue, fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss.

Stages I-IV are used to describe the progression of the disease, much like Hodgkin lymphoma, but the progression of areas of involvement is not as orderly as in Hodgkin lymphoma. Treatment includes radiation, chemotherapy, stem cell transplants, and immunotherapy medications. Treatments are targeted to specific lymphatic cells or their precursors to help slow the disease process. Prognosis depends upon the subtype of NHL.

General Resources for information in this chapter

NIH National Cancer Institute: Lymphoma-Health Professional Version

NIH National Cancer Institute: Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®)-Health Professional Version