Chapter 8: Net Neutrality and the Digital Divide

31 Pros and Cons of Net Neutrality

From Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Net_neutrality

Arguments in favor

Proponents of net neutrality include consumer advocates, human rights organizations such as Article 19,[95] online companies and some technology companies.[96] Many major Internet application companies are advocates of neutrality. Yahoo!, Vonage,[97] eBay, Amazon,[98] IAC/InterActiveCorp. Microsoft, Twitter, Tumblr, Etsy, Daily Kos, Greenpeace, along with many other companies and organizations, have also taken a stance in support of net neutrality.[99][100] Cogent Communications, an international Internet service provider, has made an announcement in favor of certain net neutrality policies.[101] In 2008, Google published a statement speaking out against letting broadband providers abuse their market power to affect access to competing applications or content. They further equated the situation to that of the telephony market, where telephone companies are not allowed to control who their customers call or what those customers are allowed to say.[4] However, Google’s support of net neutrality was called into question in 2014.[102] Several civil rights groups, such as the ACLU, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Free Press, and Fight for the Future support net neutrality.[103]

Individuals who support net neutrality include World Wide Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee,[104] Vinton Cerf,[105][106] Lawrence Lessig,[107] Robert W. McChesney, Steve Wozniak, Susan P. Crawford, Marvin Ammori, Ben Scott, David Reed,[108] and U.S. President Barack Obama.[109][110] On 10 November 2014, Obama recommended that the FCC reclassify broadband Internet service as a telecommunications service in order to preserve net neutrality.[111][112][113] On 12 November 2014, AT&T stopped build-out of their fiber network until it has “solid net neutrality rules to follow”.[114] On 31 January 2015, AP News reported that the FCC will present the notion of applying (“with some caveats”) Title II (common carrier) of the Communications Act of 1934 and section 706 of the Telecommunications act of 1996 [115] to the Internet in a vote expected on 26 February 2015.[116][117][118][119][120]

Control of data

Supporters of net neutrality want to designate cable companies as common carriers, which would require them to allow Internet service providers (ISPs) free access to cable lines, the same model used for dial-up Internet. They want to ensure that cable companies cannot screen, interrupt or filter Internet content without a court order.[121] Common carrier status would give the FCC the power to enforce net neutrality rules.[122] SaveTheInternet.com accuses cable and telecommunications companies of wanting the role of gatekeepers, being able to control which websites load quickly, load slowly, or don’t load at all. According to SaveTheInternet.com these companies want to charge content providers who require guaranteed speedy data delivery – to create advantages for their own search engines, Internet phone services, and streaming video services – and slowing access or blocking access to those of competitors.[123] Vinton Cerf, a co-inventor of the Internet Protocol and current vice president of Google argues that the Internet was designed without any authorities controlling access to new content or new services.[124] He concludes that the principles responsible for making the Internet such a success would be fundamentally undermined were broadband carriers given the ability to affect what people see and do online.[105]Cerf has also written about the importance of looking at problems like Net Neutrality through the a combination of the Internet’s layered system and the multistakeholder model that governs it.[125] He shows how challenges can arise that can implicate Net Neutrality in certain infrastructure-based cases, such as when ISPs to enter into exclusive arrangements with large building owners, leaving the residents unable to exercise any choice in broadband provider.[126]

Digital rights and freedoms

Proponents of net neutrality argue that a neutral net will foster free speech and lead to further democratic participation on the internet. Senator Al Franken from Minnesota fears that without new regulations, the major Internet Service Providers will use their position of power to stifle people’s rights. He calls net neutrality the “First Amendment issue of our time.”[127] By ensuring that all people and websites have equal access to each other, regardless of their ability to pay, proponents of net neutrality wish to prevent the need to pay for speech and the further centralization of media power. Lawrence Lessig and Robert W. McChesney argue that net neutrality ensures that the Internet remains a free and open technology, fostering democratic communication. Lessig and McChesney go on to argue that the monopolization of the Internet would stifle the diversity of independent news sources and the generation of innovative and novel web content.[107]

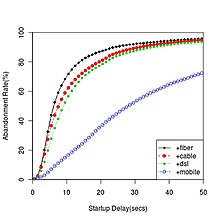

User intolerance for slow-loading sites

Users with faster Internet connectivity (e.g., fiber) abandon a slow-loading video at a faster rate than users with slower Internet connectivity (e.g., cable or mobile).[128] A “fast lane” in the Internet can irrevocably decrease the user’s tolerance to the relative slowness of the “slow lane”.

Proponents of net neutrality invoke the human psychological process of adaptation where when people get used to something better, they would not ever want to go back to something worse. In the context of the Internet, the proponents argue that a user who gets used to the “fast lane” on the Internet would find the “slow lane” intolerable in comparison, greatly disadvantaging any provider who is unable to pay for the “fast lane”. Video providers Netflix[129] and Vimeo[130] in their comments to FCC in favor of net neutrality use the research[128] of S.S. Krishnan and Ramesh Sitaraman that provides the first quantitative evidence of adaptation to speed among online video users. Their research studied the patience level of millions of Internet video users who waited for a slow-loading video to start playing. Users who had a faster Internet connectivity, such as fiber-to-the-home, demonstrated less patience and abandoned their videos sooner than similar users with slower Internet connectivity. The results demonstrate how users can get used to faster Internet connectivity, leading to higher expectation of Internet speed, and lower tolerance for any delay that occurs. Author Nicholas Carr[131]and other social commentators[132][133] have written about the habituation phenomenon by stating that a faster flow of information on the Internet can make people less patient.

Competition and innovation

Net neutrality advocates argue that allowing cable companies the right to demand a toll to guarantee quality or premium delivery would create an exploitative business model based on the ISPs position as gatekeepers.[134] Advocates warn that by charging websites for access, network owners may be able to block competitor Web sites and services, as well as refuse access to those unable to pay.[107] According to Tim Wu, cable companies plan to reserve bandwidth for their own television services, and charge companies a toll for priority service.[135] Proponents of net neutrality argue that allowing for preferential treatment of Internet traffic, or tiered service, would put newer online companies at a disadvantage and slow innovation in online services.[96] Tim Wu argues that, without network neutrality, the Internet will undergo a transformation from a market ruled by innovation to one ruled by deal-making.[135] SaveTheInternet.com argues that net neutrality puts everyone on equal terms, which helps drive innovation. They claim it is a preservation of the way the internet has always operated, where the quality of websites and services determined whether they succeeded or failed, rather than deals with ISPs.[123] Lawrence Lessig and Robert W. McChesney argue that eliminating net neutrality would lead to the Internet resembling the world of cable TV, so that access to and distribution of content would be managed by a handful of massive, near monopolistic companies, though there are multiple service providers in each region. These companies would then control what is seen as well as how much it costs to see it. Speedy and secure Internet use for such industries as health care, finance, retailing, and gambling could be subject to large fees charged by these companies. They further explain that a majority of the great innovators in the history of the Internet started with little capital in their garages, inspired by great ideas. This was possible because the protections of net neutrality ensured limited control by owners of the networks, maximal competition in this space, and permitted innovators from outside access to the network. Internet content was guaranteed a free and highly competitive space by the existence of net neutrality.[107]

Preserving Internet standards

Net neutrality advocates have sponsored legislation claiming that authorizing incumbent network providers to override transport and application layer separation on the Internet would signal the decline of fundamental Internet standards and international consensus authority. Further, the legislation asserts that bit-shaping the transport of application data will undermine the transport layer’s designed flexibility.[136]

Preventing pseudo-services

Alok Bhardwaj, founder of Epic Privacy Browser, argues that any violations to network neutrality, realistically speaking, will not involve genuine investment but rather payoffs for unnecessary and dubious services. He believes that it is unlikely that new investment will be made to lay special networks for particular websites to reach end-users faster. Rather, he believes that non-net neutrality will involve leveraging quality of service to extract remuneration from websites that want to avoid being slowed down.[137][138]

End-to-end principle

Some advocates say network neutrality is needed in order to maintain the end-to-end principle. According to Lawrence Lessig and Robert W. McChesney, all content must be treated the same and must move at the same speed in order for net neutrality to be true. They say that it is this simple but brilliant end-to-end aspect that has allowed the Internet to act as a powerful force for economic and social good.[107] Under this principle, a neutral network is a dumb network, merely passing packets regardless of the applications they support. This point of view was expressed by David S. Isenberg in his paper, “The Rise of the Stupid Network”. He states that the vision of an intelligent network is being replaced by a new network philosophy and architecture in which the network is designed for always-on use, not intermittence and scarcity. Rather than intelligence being designed into the network itself, the intelligence would be pushed out to the end-user’s device; and the network would be designed simply to deliver bits without fancy network routing or smart number translation. The data would be in control, telling the network where it should be sent. End-user devices would then be allowed to behave flexibly, as bits would essentially be free and there would be no assumption that the data is of a single data rate or data type.[139]

Contrary to this idea, the research paper titled End-to-end arguments in system design by Saltzer, Reed, and Clark[140] argues that network intelligence doesn’t relieve end systems of the requirement to check inbound data for errors and to rate-limit the sender, nor for a wholesale removal of intelligence from the network core.

Arguments against

Opponents of net neutrality regulations include civil rights groups, economists, internet providers and technologists. Among corporations, opponents include AT&T, Verizon, IBM, Intel, Cisco, Nokia, Qualcomm, Broadcom, Juniper, dLink, Wintel, Alcatel-Lucent, Corning, Panasonic, Ericsson, and others.[73][141][142] Notable technologists who oppose net neutrality include Marc Andreessen, Scott McNealy, Peter Thiel, David Farber, Nicholas Negroponte, Rajeev Suri, Jeff Pulver, John Perry Barlow, and Bob Kahn.[143][144][145][146][147][148][149][150][151][152]

Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker‘s paper titled, “Net Neutrality and Consumer Welfare”, published by the Journal of Competition Law & Economics, alleges that claims by net neutrality proponents “do not provide a compelling rationale for regulation” because there is “significant and growing competition” among broadband access providers.[144][153] Google Chairman Eric Schmidt states that, while Google views that similar data types should not be discriminated against, it is okay to discriminate across different data types—a position that both Google and Verizon generally agree on, according to Schmidt.[154][155] According to the Journal, when President Barack Obama announced his support for strong net neutrality rules late in 2014, Schmidt told a top White House official the president was making a mistake.[155]

Several civil rights groups, such as the National Urban League, Jesse Jackson‘s Rainbow/PUSH, and League of United Latin American Citizens, also oppose Title II net neutrality regulations,[156] who said that the call to regulate broadband Internet service as a utility would harm minority communities by stifling investment in undeserved areas.[157][158]

A number of other opponents created Hands Off The Internet,[159] a website created in 2006 to promote arguments against internet regulation. Principal financial support for the website came from AT&T, and members included BellSouth, Alcatel, Cingular, and Citizens Against Government Waste.[160][161][162][163][164]

Robert Pepper, a senior managing director, global advanced technology policy, at Cisco Systems, and former FCC chief of policy development, says: “The supporters of net neutrality regulation believe that more rules are necessary. In their view, without greater regulation, service providers might parcel out bandwidth or services, creating a bifurcated world in which the wealthy enjoy first-class Internet access, while everyone else is left with slow connections and degraded content. That scenario, however, is a false paradigm. Such an all-or-nothing world doesn’t exist today, nor will it exist in the future. Without additional regulation, service providers are likely to continue doing what they are doing. They will continue to offer a variety of broadband service plans at a variety of price points to suit every type of consumer”.[165] Computer scientist Bob Kahn [150] has said net neutrality is a slogan that would freeze innovation in the core of the Internet.[143]

Farber has written and spoken strongly in favor of continued research and development on core Internet protocols. He joined academic colleagues Michael Katz, Christopher Yoo, and Gerald Faulhaber in an op-ed for the Washington Post strongly critical of network neutrality, essentially stating that while the Internet is in need of remodeling, congressional action aimed at protecting the best parts of the current Internet could interfere with efforts to build a replacement.[166]

Reduction in innovation and investments

According to a letter to key Congressional and FCC leaders sent by 60 major ISP technology suppliers including IBM, Intel, Qualcomm, and Cisco, Title II regulation of the internet “means that instead of billions of broadband investment driving other sectors of the economy forward, any reduction in this spending will stifle growth across the entire economy. This is not idle speculation or fear mongering…Title II is going to lead to a slowdown, if not a hold, in broadband build out, because if you don’t know that you can recover on your investment, you won’t make it.”[73][167][168][169] According to the Wall Street Journal, in one of Google’s few lobbying sessions with FCC officials, the company urged the agency to craft rules that encourage investment in broadband Internet networks—a position that mirrors the argument made by opponents of strong net neutrality rules, such as AT&T and Comcast.[155] Opponents of net neutrality argue that prioritization of bandwidth is necessary for future innovation on the Internet.[142] Telecommunications providers such as telephone and cable companies, and some technology companies that supply networking gear, argue telecom providers should have the ability to provide preferential treatment in the form of tiered services, for example by giving online companies willing to pay the ability to transfer their data packets faster than other Internet traffic.[170] The added revenue from such services could be used to pay for the building of increased broadband access to more consumers.[96]

Opponents say that net neutrality would make it more difficult for Internet service providers (ISPs) and other network operators to recoup their investments in broadband networks.[171] John Thorne, senior vice president and deputy general counsel of Verizon, a broadband and telecommunications company, has argued that they will have no incentive to make large investments to develop advanced fibre-optic networks if they are prohibited from charging higher preferred access fees to companies that wish to take advantage of the expanded capabilities of such networks. Thorne and other ISPs have accused Google and Skype of freeloading or free riding for using a network of lines and cables the phone company spent billions of dollars to build.[142][172][173] Marc Andreessen states that “a pure net neutrality view is difficult to sustain if you also want to have continued investment in broadband networks. If you’re a large telco right now, you spend on the order of $20 billion a year on capex [capital expenditure]. You need to know how you’re going to get a return on that investment. If you have these pure net neutrality rules where you can never charge a company like Netflix anything, you’re not ever going to get a return on continued network investment — which means you’ll stop investing in the network. And I would not want to be sitting here 10 or 20 years from now with the same broadband speeds we’re getting today.”[174]

Counterweight to server-side non-neutrality

Those in favor of forms of non-neutral tiered Internet access argue that the Internet is already not a level playing field: large companies achieve a performance advantage over smaller competitors by providing more and better-quality servers and buying high-bandwidth services. Should prices drop for lower levels of access, or access to only certain protocols, for instance, a change of this type would make Internet usage more neutral, with respect to the needs of those individuals and corporations specifically seeking differentiated tiers of service. Network expert[175] Richard Bennett has written, “A richly funded Web site, which delivers data faster than its competitors to the front porches of the Internet service providers, wants it delivered the rest of the way on an equal basis. This system, which Google calls broadband neutrality, actually preserves a more fundamental inequality.”[176]

Broadband infrastructure

Proponents of net neutrality regulations say network operators have continued to under-invest in infrastructure.[177] However, according to Copenhagen Economics, US investment in telecom infrastructure is 50 percent higher that of the European Union. As a share of GDP, The US’s broadband investment rate per GDP trails only the UK and South Korea slightly, but exceeds Japan, Canada, Italy, Germany, and France sizably.[178] On broadband speed, Akamai reported that the US trails only South Korea and Japan among its major trading partners, and trails only Japan in the G-7 in both average peak connection speed and percentage of the population connection at 10 Mbit/s or higher, but are substantially ahead of most of its other major trading partners.[178]

The White House reported in June 2013 that U.S. connection speeds are “the fastest compared to other countries with either a similar population or land mass.”[179] Akamai’s report on “The State of the Internet” in the 2nd quarter of 2014 says “a total of 39 states saw 4K readiness rate more than double over the past year.” In other words, as ZDNet reports, those states saw a “major” increase in the availability of the 15Mbit/s speed needed for 4K video.[180] According to the Progressive Policy Institute and ITU data, the United States has the most affordable entry-level prices for fixed broadband in the OECD.[178][181]

In Indonesia, there is a very high number of Internet connections that are subjected to exclusive deals between the ISP and the building owner, and changing this dynamic could unlock much more consumer choice and higher speeds.[126] FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai and Federal Election Commission’s Lee Goldman wrote in a Politico piece in February 2015, “Compare Europe, which has long had utility-style regulations, with the United States, which has embraced a light-touch regulatory model. Broadband speeds in the United States, both wired and wireless, are significantly faster than those in Europe. Broadband investment in the United States is several multiples that of Europe. And broadband’s reach is much wider in the United States, despite its much lower population density.” [182]

Significant and growing competition

A 2010 paper on net neutrality by Nobel Prize economist Gary Becker and his colleagues stated that “there is significant and growing competition among broadband access providers and that few significant competitive problems have been observed to date, suggesting that there is no compelling competitive rationale for such regulation.”[153] Becker and fellow economists Dennis Carlton and Hal Sidler found that “Between mid-2002 and mid-2008, the number of high-speed broadband access lines in the United States grew from 16 million to nearly 133 million, and the number of residential broadband lines grew from 14 million to nearly 80 million. Internet traffic roughly tripled between 2007 and 2009. At the same time, prices for broadband Internet access services have fallen sharply.”[153] The PPI reports that the profit margins of U.S. broadband providers are generally one-sixth to one-eighth of companies that use broadband (such as Apple or Google), contradicting the idea of monopolistic price-gouging by providers.[178]

Broadband choice

A report by the Progressive Policy Institute in June 2014 argues that nearly every American can choose from at least 5-6 broadband internet service providers, despite claims that there are only a ‘small number’ of broadband providers.[178] Citing research from the FCC, the Institute wrote that 90 percent of American households have access to at least one wired and one wireless broadband provider at speeds of at least 4 Mbit/s (500 kbyte/s) downstream and 1 Mbit/s (125 kbyte/s) upstream and that nearly 88 percent of Americans can choose from at least two wired providers of broadband disregarding speed (typically choosing between a cable and telco offering). Further, three of the four national wireless companies report that they offer 4G LTE to between 250-300 million Americans, with the fourth (T-Mobile) sitting at 209 million and counting.[178] Similarly, the FCC reported in June 2008 that 99.8 percent of zip codes in the United States had two or more providers of high speed Internet lines available, and 94.6 percent of zip codes had four or more providers, as reported by University of Chicago economists Gary Becker, Dennis Carlton, and Hal Sider in a 2010 paper.[153]

When FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler redefined broadband from 4 Mbit/s to 25 Mbit/s (3.125 MB/s) or greater in January 2015, FCC commissioners Ajit Pai and Mike O’Reilly believed the redefinition was to set up the agency’s intent to settle the net neutrality fight with new regulations. The commissioners argued that the stricter speed guidelines painted the broadband industry as less competitive, justifying the FCC’s moves with Title II net neutrality regulations.[183]

Deterring competition

FCC commissioner Ajit Pai states that the FCC completely brushes away the concerns of smaller competitors who are going to be subject to various taxes, such as state property taxes and general receipts taxes.[184] As a result, according to Pai, that does nothing to create more competition within the market.[184] According to Pai, the FCC’s ruling to impose Title II regulations is opposed by the country’s smallest private competitors and many municipal broadband providers.[185] In his dissent, Pai noted that 142 wireless ISPs (WISPs) said that FCC’s new “regulatory intrusion into our businesses…would likely force us to raise prices, delay deployment expansion, or both.” He also noted that 24 of the country’s smallest ISPs, each with fewer than 1,000 residential broadband customers, wrote to the FCC stating that Title II “will badly strain our limited resources” because they “have no in-house attorneys and no budget line items for outside counsel.” Further, another 43 municipal broadband providers told the FCC that Title II “will trigger consequences beyond the Commission’s control and risk serious harm to our ability to fund and deploy broadband without bringing any concrete benefit for consumers or edge providers that the market is not already proving today without the aid of any additional regulation.”[141]

Potentially increased taxes

FCC commissioner Ajit Pai, who opposed the net neutrality ruling, claims that the ruling issued by the FCC to impose Title II regulations explicitly opens the door to billions of dollars in new fees and taxes on broadband by subjecting them to the telephone-style taxes under the Universal Service Fund. Net neutrality proponent Free Press argues that, “the average potential increase in taxes and fees per household would be far less” than the estimate given by net neutrality opponents, and that if there were to be additional taxes, the tax figure may be around $4 billion. Under favorable circumstances, “the increase would be exactly zero.”[186] Meanwhile, the Progressive Policy Institute claims that Title II could trigger taxes and fees up to $11 billion a year.[187]Financial website Nerd Wallet did their own assessment and settled on a possible $6.25 billion tax impact, estimating that the average American household may see their tax bill increase $67 annually.[187]

FCC spokesperson Kim Hart said that the ruling “does not raise taxes or fees. Period.”[187] However, the opposing commissioner, Ajit Pai, claims that “the plan explicitly opens the door to billions of dollars in new taxes on broadband…These new taxes will mean higher prices for consumers and more hidden fees that they have to pay.” [188] Pai explained that, “One avenue for higher bills is the new taxes and fees that will be applied to broadband. Here’s the background. If you look at your phone bill, you’ll see a ‘Universal Service Fee,’ or something like it. These fees —- what most Americans would call taxes — are paid by Americans on their telephone service. They funnel about $9 billion each year through the FCC. Consumers haven’t had to pay these taxes on their broadband bills because broadband has never before been a Title II service. But now it is. And so the Order explicitly opens the door to billions of dollars in new taxes.”[141]

Prevent overuse of bandwidth

Since the early 1990s, Internet traffic has increased steadily. The arrival of picture-rich websites and MP3s led to a sharp increase in the mid-1990s followed by a subsequent sharp increase since 2003 as video streaming and Peer-to-peer file sharing became more common.[189][190] In reaction to companies including YouTube, as well as smaller companies starting to offer free video content, using substantial amounts of bandwidth, at least one Internet service provider (ISP), SBC Communications (now AT&T Inc.), has suggested that it should have the right to charge these companies for making their content available over the provider’s network.[191]

Bret Swanson of the Wall Street Journal wrote in 2007 that the popular websites of that time, including YouTube, MySpace, and blogs, were put at risk by net neutrality. He noted that, at the time, YouTube streamed as much data in three months as the world’s radio, cable and broadcast television channels did in one year, 75 petabytes. He argued that networks were not remotely prepared to handle the amount of data required to run these sites. He also argued that net neutrality would prevent broadband networks from being built, which would limit available bandwidth and thus endanger innovation.[192] One example of these concerns was the “series of tubes” analogy, which was presented by US senator Ted Stevens during a committee hearing in the US senate in 2006.

High costs to entry for cable broadband

According to a Wired magazine article by TechFreedom’s Berin Szoka, Matthew Starr, and Jon Henke, local governments and public utilities impose the most significant barriers to entry for more cable broadband competition: “While popular arguments focus on supposed ‘monopolists’ such as big cable companies, it’s government that’s really to blame.” The authors state that local governments and their public utilities charge ISPs far more than they actually cost and have the final say on whether an ISP can build a network. The public officials determine what requirements an ISP must meet to get approval for access to publicly owned “rights of way” (which lets them place their wires), thus reducing the number of potential competitors who can profitably deploy Internet service—such as AT&T’s U-Verse, Google Fiber, and Verizon FiOS. Kickbacks may include municipal requirements for ISPs such as building out service where it isn’t demanded, donating equipment, and delivering free broadband to government buildings.[193]

Unnecessary regulations

According to PayPal founder and Facebook investor Peter Thiel, “Net neutrality has not been necessary to date. I don’t see any reason why it’s suddenly become important, when the Internet has functioned quite well for the past 15 years without it…. Government attempts to regulate technology have been extraordinarily counterproductive in the past.”[144] Max Levchin, the other co-founder of PayPal, echoed similar statements, telling CNBC, “The Internet is not broken, and it got here without government regulation and probably in part because of lack of government regulation.”[194] Opponents of new federal net neutrality policies point to the success of the internet as a sign that new regulations are not necessary. They argue that the freedom which websites, ISPs and consumers have had to settle their own disputes and compete through innovation is the reason why the internet has been such a rapid success. One of Congress’s most outspoken critics of net neutrality regulations is Senator Ted Cruz from Texas, who points out that “innovation [on the internet] is happening without having to go to government and say ‘Mother, may I?’ What happens when the government starts regulating a service as a public utility is it calcifies everything and freezes it in place.”[195] In regulating how the internet is provided, opponents argue that the government will hinder innovation on the web.

FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai, who was one of the two commissioners who opposed the net neutrality proposal, criticized the FCC’s ruling on internet neutrality, stating that the perceived threats from ISPs to deceive consumers, degrade content, or disfavor the content that they don’t like are non-existent: “The evidence of these continuing threats? There is none; it’s all anecdote, hypothesis, and hysteria. A small ISP in North Carolina allegedly blocked VoIP calls a decade ago. Comcast capped BitTorrent traffic to ease upload congestion eight years ago. Apple introduced Facetime over Wi-Fi first, cellular networks later. Examples this picayune and stale aren’t enough to tell a coherent story about net neutrality. The bogeyman never had it so easy.”[141] FCC Commissioner Mike O’Reilly, the other opposing commissioner, also claims that the ruling is a solution to a hypothetical problem, “Even after enduring three weeks of spin, it is hard for me to believe that the Commission is establishing an entire Title II/net neutrality regime to protect against hypothetical harms. There is not a shred of evidence that any aspect of this structure is necessary. The D.C. Circuit called the prior, scaled-down version a ‘prophylactic’ approach. I call it guilt by imagination.”[196] In a Chicago Tribune article, FCC Commissioner Pai and Joshua Wright of the Federal Trade Commission argue that “the Internet isn’t broken, and we don’t need the president’s plan to ‘fix’ it. Quite the opposite. The Internet is an unparalleled success story. It is a free, open and thriving platform.”[74]