Chapter 8: Net Neutrality and the Digital Divide

32 The Digital Divide

The Digital Divide

From Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_divide

A digital divide is an economic and social inequality with regard to access to, use of, or impact of information and communication technologies(ICT).[1] The divide within countries (such as the digital divide in the United States) may refer to inequalities between individuals, households, businesses, or geographic areas, usually at different socioeconomic levels or other demographic categories. The divide between differing countries or regions of the world is referred to as the global digital divide,[1][2] examining this technological gap between developing and developed countries on an international scale.[3]

Definitions and usage

The term digital divide describes a gap in terms of access to and usage of information and communication technology. It was traditionally considered to be a question of having or not having access,[4] but with a global mobile phone penetration of over 95%,[5] it is becoming a relative inequality between those who have more and less bandwidth[6] and more or less skills.[7][8][9][10] Conceptualizations of the digital divide have been described as “who, with which characteristics, connects how to what”:[11]

- Who is the subject that connects: individuals, organizations, enterprises, schools, hospitals, countries, etc.

- Which characteristics or attributes are distinguished to describe the divide: income, education, age, geographic location, motivation, reason not to use, etc.

- How sophisticated is the usage: mere access, retrieval, interactivity, intensive and extensive in usage, innovative contributions, etc.

- To what does the subject connect: fixed or mobile, Internet or telephony, digital TV, broadband, etc.

Different authors focus on different aspects, which leads to a large variety of definitions of the digital divide. “For example, counting with only 3 different choices of subjects (individuals, organizations, or countries), each with 4 characteristics (age, wealth, geography, sector), distinguishing between 3 levels of digital adoption (access, actual usage and effective adoption), and 6 types of technologies (fixed phone, mobile… Internet…), already results in 3x4x3x6 = 216 different ways to define the digital divide. Each one of them seems equally reasonable and depends on the objective pursued by the analyst”.[11]

Means of connectivity

Infrastructure

The infrastructure by which individuals, households, businesses, and communities connect to the Internet address the physical mediums that people use to connect to the Internet such as desktop computers, laptops, basic mobile phones or smart phones, iPods or other MP3 players, gaming consoles such as Xbox or PlayStation, electronic book readers, and tablets such as iPads.[12]

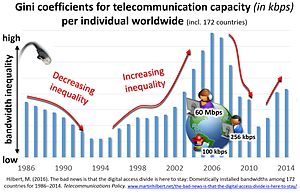

The digital divide measured in terms of bandwidth is not closing, but fluctuating up and down. Gini coefficients for telecommunication capacity (in kbit/s) among individuals worldwide.[13]

Traditionally the nature of the divide has been measured in terms of the existing numbers of subscriptions and digital devices. Given the increasing number of such devices, some have concluded that the digital divide among individuals has increasingly been closing as the result of a natural and almost automatic process.[4][14] Others point to persistent lower levels of connectivity among women, racial and ethnic minorities, people with lower incomes, rural residents, and less educated people as evidence that addressing inequalities in access to and use of the medium will require much more than the passing of time.[7][15][16] Recent studies have measured the digital divide not in terms of technological devices, but in terms of the existing bandwidth per individual (in kbit/s per capita).[6][13] As shown in the Figure on the side, the digital divide in kbit/s is not monotonically decreasing, but re-opens up with each new innovation. For example, “the massive diffusion of narrow-band Internet and mobile phones during the late 1990s” increased digital inequality, as well as “the initial introduction of broadband DSL and cable modems during 2003–2004 increased levels of inequality”.[6] This is because a new kind of connectivity is never introduced instantaneously and uniformly to society as a whole at once, but diffuses slowly through social networks. As shown by the Figure, during the mid-2000s, communication capacity was more unequally distributed than during the late 1980s, when only fixed-line phones existed. The most recent increase in digital equality stems from the massive diffusion of the latest digital innovations (i.e. fixed and mobile broadband infrastructures, e.g. 3G and fiber optics FTTH).[17] Measurement methodologies of the digital divide, and more specifically an Integrated Iterative Approach General Framework (Integrated Contextual Iterative Approach – ICI) and the digital divide modeling theory under measurement model DDG (Digital Divide Gap) are used to analyze the gap existing between developed and developing countries, and the gap among the 27 members-states of the European Union.[18][19]

The bit as the unifying variable

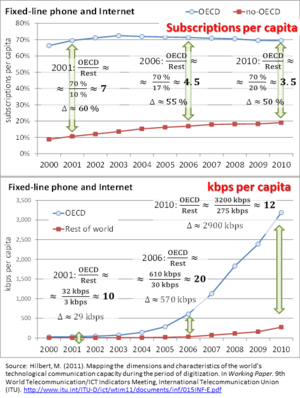

Fixed-line phone and Internet 2000–2010: subscriptions (top) and kbit/s (bottom) per capita[20]

Instead of tracking various kinds of digital divides among fixed and mobile phones, narrow- and broadband Internet, digital TV, etc., it has recently been suggested to simply measure the amount of kbit/s per actor.[6][13][21][22] This approach has shown that the digital divide in kbit/s per capita is actually widening in relative terms: “While the average inhabitant of the developed world counted with some 40 kbit/s more than the average member of the information society in developing countries in 2001, this gap grew to over 3 Mbit/s per capita in 2010.”[22] The upper graph of the Figure on the side shows that the divide between developed and developing countries has been diminishing when measured in terms of subscriptions per capita. In 2001, fixed-line telecommunication penetration reached 70% of society in developed OECD countries and 10% of the developing world. This resulted in a ratio of 7 to 1 (divide in relative terms) or a difference of 60% (divide in measured in absolute terms). During the next decade, fixed-line penetration stayed almost constant in OECD countries (at 70%), while the rest of the world started a catch-up, closing the divide to a ratio of 3.5 to 1. The lower graph shows the divide not in terms of ICT devices, but in terms of kbit/s per inhabitant. While the average member of developed countries counted with 29 kbit/s more than a person in developing countries in 2001, this difference got multiplied by a factor of one thousand (to a difference of 2900 kbit/s). In relative terms, the fixed-line capacity divide was even worse during the introduction of broadband Internet at the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, when the OECD counted with 20 times more capacity per capita than the rest of the world.[6] This shows the importance of measuring the divide in terms of kbit/s, and not merely to count devices. The International Telecommunications Union concludes that “the bit becomes a unifying variable enabling comparisons and aggregations across different kinds of communication technologies”.[23]

Skills and digital literacy

However, research shows that the digital divide is more than just an access issue and cannot be alleviated merely by providing the necessary equipment. There are at least three factors at play: information accessibility, information utilization and information receptiveness. More than just accessibility, individuals need to know how to make use of the information and communication tools once they exist within a community.[24] Information professionals have the ability to help bridge the gap by providing reference and information services to help individuals learn and utilize the technologies to which they do have access, regardless of the economic status of the individual seeking help.[25]

Location

Internet connectivity can be utilized at a variety of locations such as homes, offices, schools, libraries, public spaces, Internet cafe and others. There are also varying levels of connectivity in rural, suburban, and urban areas.[26][27]

Applications

Common Sense Media, a nonprofit group based in San Francisco, surveyed almost 1,400 parents and reported in 2011 that 47 percent of families with incomes more than $75,000 had downloaded apps for their children, while only 14 percent of families earning less than $30,000 had done so.[28]

Reasons and correlating variables

The gap in a digital divide may exist for a number of reasons. Obtaining access to ICTs and using them actively has been linked to a number of demographic and socio-economic characteristics: among them income, education, race, gender, geographic location (urban-rural), age, skills, awareness, political, cultural and psychological attitudes.[29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36] Multiple regression analysis across countries has shown that income levels and educational attainment are identified as providing the most powerful explanatory variables for ICT access and usage.[37] Evidence was found that caucasians are much more likely than non-caucasians to own a computer as well as have access to the Internet in their homes. As for geographic location, people living in urban centers have more access and show more usage of computer services than those in rural areas. Gender was previously thought to provide an explanation for the digital divide, many thinking ICT were male gendered, but controlled statistical analysis has shown that income, education and employment act as confounding variables and that women with the same level of income, education and employment actually embrace ICT more than men (see Women and ICT4D).[38]

One telling fact is that “as income rises so does Internet use […]”, strongly suggesting that the digital divide persists at least in part due to income disparities.[39] Most commonly, a digital divide stems from poverty and the economic barriers that limit resources and prevent people from obtaining or otherwise using newer technologies.

In research, while each explanation is examined, others must be controlled in order to eliminate interaction effects or mediating variables,[29] but these explanations are meant to stand as general trends, not direct causes. Each component can be looked at from different angles, which leads to a myriad of ways to look at (or define) the digital divide. For example, measurements for the intensity of usage, such as incidence and frequency, vary by study. Some report usage as access to Internet and ICTs while others report usage as having previously connected to the Internet. Some studies focus on specific technologies, others on a combination (such as Infostate, proposed by Orbicom-UNESCO, the Digital Opportunity Index, or ITU‘s ICT Development Index). Based on different answers to the questions of who, with which kinds of characteristics, connects how and why, to what there are hundreds of alternatives ways to define the digital divide.[11] “The new consensus recognizes that the key question is not how to connect people to a specific network through a specific device, but how to extend the expected gains from new ICTs”.[40] In short, the desired impact and “the end justifies the definition” of the digital divide.[11]

Economic gap in the United States

During the mid-1990s the US Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications & Information Administration (NTIA) began publishing reports about the Internet and access to and usage of the resource. The first of three reports is entitled “Falling Through the Net: A Survey of the ‘Have Nots’ in Rural and Urban America” (1995),[41] the second is “Falling Through the Net II: New Data on the Digital Divide” (1998),[42] and the final report “Falling Through the Net: Defining the Digital Divide” (1999).[43] The NTIA’s final report attempted to clearly define the term digital divide; “the digital divide—the divide between those with access to new technologies and those without—is now one of America’s leading economic and civil rights issues. This report will help clarify which Americans are falling further behind, so that we can take concrete steps to redress this gap.”[43] Since the introduction of the NTIA reports, much of the early, relevant literature began to reference the NTIA’s digital divide definition. The digital divide is commonly defined as being between the “haves” and “have-nots.”[43][44]

Overcoming the divide

An individual must be able to connect in order to achieve enhancement of social and cultural capital as well as achieve mass economic gains in productivity. Therefore, access is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for overcoming the digital divide. Access to ICT meets significant challenges that stem from income restrictions. The borderline between ICT as a necessity good and ICT as a luxury good is roughly around the “magical number” of US$10 per person per month, or US$120 per year,[37] which means that people consider ICT expenditure of US$120 per year as a basic necessity. Since more than 40% of the world population lives on less than US$2 per day, and around 20% live on less than US$1 per day (or less than US$365 per year), these income segments would have to spend one third of their income on ICT (120/365 = 33%). The global average of ICT spending is at a mere 3% of income.[37] Potential solutions include driving down the costs of ICT, which includes low cost technologies and shared access through Telecentres.

Furthermore, even though individuals might be capable of accessing the Internet, many are thwarted by barriers to entry such as a lack of means to infrastructure or the inability to comprehend the information that the Internet provides. Lack of adequate infrastructure and lack of knowledge are two major obstacles that impede mass connectivity. These barriers limit individuals’ capabilities in what they can do and what they can achieve in accessing technology. Some individuals have the ability to connect, but they do not have the knowledge to use what information ICTs and Internet technologies provide them. This leads to a focus on capabilities and skills, as well as awareness to move from mere access to effective usage of ICT.[8]

The United Nations is aiming to raise awareness of the divide by way of the World Information Society Day which has taken place yearly since May 17, 2006.[45] It also set up the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Task Force in November 2001.[46] Later UN initiatives in this area are the World Summit on the Information Society, which was set up in 2003, and the Internet Governance Forum, set up in 2006.

In the year 2000, the United Nations Volunteers (UNV) programme launched its Online Volunteering service,[47] which uses ICT as a vehicle for and in support of volunteering. It constitutes an example of a volunteering initiative that effectively contributes to bridge the digital divide. ICT-enabled volunteering has a clear added value for development. If more people collaborate online with more development institutions and initiatives, this will imply an increase in person-hours dedicated to development cooperation at essentially no additional cost. This is the most visible effect of online volunteering for human development.[48]

Social media websites serve as both manifestations of and means by which to combat the digital divide. The former describes phenomena such as the divided users demographics that make up sites such as Facebook and Myspace or Word Press and Tumblr. Each of these sites host thriving communities that engage with otherwise marginalized populations. An example of this is the large online community devoted to Afrofuturism, a discourse that critiques dominant structures of power by merging themes of science fiction and blackness. Social media brings together minds that may not otherwise meet, allowing for the free exchange of ideas and empowerment of marginalized discourses.

Libraries

A laptop lending kiosk at Texas A&M University–Commerce‘s Gee Library

Attempts to bridge the digital divide include a program developed in Durban, South Africa, where very low access to technology and a lack of documented cultural heritage has motivated the creation of an “online indigenous digital library as part of public library services.”[49] This project has the potential to narrow the digital divide by not only giving the people of the Durban area access to this digital resource, but also by incorporating the community members into the process of creating it.

Another attempt to narrow the digital divide takes the form of One Laptop Per Child (OLPC).[50] This organization, founded in 2005, provides inexpensively produced “XO” laptops (dubbed the “$100 laptop”, though actual production costs vary) to children residing in poor and isolated regions within developing countries. Each laptop belongs to an individual child and provides a gateway to digital learning and Internet access. The XO laptops are specifically designed to withstand more abuse than higher-end machines, and they contain features in context to the unique conditions that remote villages present. Each laptop is constructed to use as little power as possible, have a sunlight-readable screen, and is capable of automatically networking with other XO laptops in order to access the Internet—as many as 500 machines can share a single point of access.[50]

To address the divide The Gates Foundation began the Gates Library Initiative. The Gates Foundation focused on providing more than just access, they placed computers and provided training in libraries. In this manner if users began to struggle while using a computer, the user was in a setting where assistance and guidance was available. Further, the Gates Library Initiative was “modeled on the old-fashioned life preserver: The support needs to be around you to keep you afloat.”[9]

In nations where poverty compounds effects of the digital divide, programs are emerging to counter those trends. Prior conditions in Kenya—lack of funding, language and technology illiteracy contributed to an overall lack of computer skills and educational advancement for those citizens. This slowly began to change when foreign investment began. In the early 2000s, The Carnegie Foundation funded a revitalization project through the Kenya National Library Service (KNLS). Those resources enabled public libraries to provide information and communication technologies (ICT) to their patrons. In 2012, public libraries in the Busia and Kiberia communities introduced technology resources to supplement curriculum for primary schools. By 2013, the program expanded into ten schools.[51]

Effective use

Community Informatics (CI) provides a somewhat different approach to addressing the digital divide by focusing on issues of “use” rather than simply “access”. CI is concerned with ensuring the opportunity not only for ICT access at the community level but also, according to Michael Gurstein, that the means for the “effective use” of ICTs for community betterment and empowerment are available.[52] Gurstein has also extended the discussion of the digital divide to include issues around access to and the use of “open data” and coined the term “data divide” to refer to this issue area.[53]

Implications

Social capital

Once an individual is connected, Internet connectivity and ICTs can enhance his or her future social and cultural capital. Social capital is acquired through repeated interactions with other individuals or groups of individuals. Connecting to the Internet creates another set of means by which to achieve repeated interactions. ICTs and Internet connectivity enable repeated interactions through access to social networks, chat rooms, and gaming sites. Once an individual has access to connectivity, obtains infrastructure by which to connect, and can understand and use the information that ICTs and connectivity provide, that individual is capable of becoming a “digital citizen”.[29]

Criticisms

Knowledge divide

Since gender, age, racial, income, and educational gaps in the digital divide have lessened compared to past levels, some researchers suggest that the digital divide is shifting from a gap in access and connectivity to ICTs to a knowledge divide.[54] A knowledge divide concerning technology presents the possibility that the gap has moved beyond access and having the resources to connect to ICTs to interpreting and understanding information presented once connected.[55]

Second-level digital divide

The second-level digital divide, also referred to as the production gap, describes the gap that separates the consumers of content on the Internet from the producers of content.[56] As the technological digital divide is decreasing between those with access to the Internet and those without, the meaning of the term digital divide is evolving.[54] Previously, digital divide research has focused on accessibility to the Internet and Internet consumption. However, with more and more of the population with access to the Internet, researchers are examining how people use the Internet to create content and what impact socioeconomics are having on user behavior.[10][57] New applications have made it possible for anyone with a computer and an Internet connection to be a creator of content, yet the majority of user generated content available widely on the Internet, like public blogs, is created by a small portion of the Internet using population. Web 2.0 technologies like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Blogs enable users to participate online and create content without having to understand how the technology actually works, leading to an ever increasing digital divide between those who have the skills and understanding to interact more fully with the technology and those who are passive consumers of it.[56] Many are only nominal content creators through the use of Web 2.0, posting photos and status updates on Facebook, but not truly interacting with the technology.

Some of the reasons for this production gap include material factors like the type of Internet connection one has and the frequency of access to the Internet. The more frequently a person has access to the Internet and the faster the connection, the more opportunities they have to gain the technology skills and the more time they have to be creative.[58]

Other reasons include cultural factors often associated with class and socioeconomic status. Users of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to participate in content creation due to disadvantages in education and lack of the necessary free time for the work involved in blog or web site creation and maintenance.[58] Additionally, there is evidence to support the existence of the second-level digital divide at the K-12 level based on how educators’ use technology for instruction.[59] Schools’ economic factors have been found to explain variation in how teachers use technology to promote higher-order thinking skills.[59]

The global digital divide

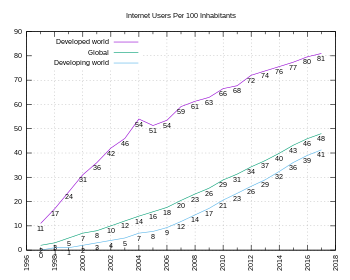

Internet users per 100 inhabitantsSource: International Telecommunications Union.[60][61]

Global bandwidth concentration: 3 countries have almost 50 %; 10 countries almost 75 %[13]

| 2005 | 2010 | 2014a | |

| World population[62] | 6.5 billion | 6.9 billion | 7.2 billion |

| Not using the Internet | 84% | 70% | 60% |

| Using the Internet | 16% | 30% | 40% |

| Users in the developing world | 8% | 21% | 32% |

| Users in the developed world | 51% | 67% | 78% |

| a Estimate. Source: International Telecommunications Union.[63] |

|||

| 2005 | 2010 | 2014a | |

| Africa | 2% | 10% | 19% |

| Americas | 36% | 49% | 65% |

| Arab States | 8% | 26% | 41% |

| Asia and Pacific | 9% | 23% | 32% |

| Commonwealth of Independent States |

10% | 34% | 56% |

| Europe | 46% | 67% | 75% |

| a Estimate. Source: International Telecommunications Union.[63] |

|||

Mobile broadband Internet subscriptions in 2012

as a percentage of a country’s populationSource: International Telecommunications Union.[64]

| 2007 | 2010 | 2014a | |

| World population[62] | 6.6 billion | 6.9 billion | 7.2 billion |

| Fixed broadband | 5% | 8% | 10% |

| Developing world | 2% | 4% | 6% |

| Developed world | 18% | 24% | 27% |

| Mobile broadband | 4% | 11% | 32% |

| Developing world | 1% | 4% | 21% |

| Developed world | 19% | 43% | 84% |

| a Estimate. Source: International Telecommunications Union.[63] |

|||

| Fixed subscriptions: | 2007 | 2010 | 2014a |

| Africa | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.4% |

| Americas | 11% | 14% | 17% |

| Arab States | 1% | 2% | 3% |

| Asia and Pacific | 3% | 6% | 8% |

| Commonwealth of Independent States |

2% | 8% | 14% |

| Europe | 18% | 24% | 28% |

| Mobile subscriptions: | 2007 | 2010 | 2014a |

| Africa | 0.2% | 2% | 19% |

| Americas | 6% | 23% | 59% |

| Arab States | 0.8% | 5% | 25% |

| Asia and Pacific | 3% | 7% | 23% |

| Commonwealth of Independent States |

0.2% | 22% | 49% |

| Europe | 15% | 29% | 64% |

| a Estimate. Source: International Telecommunications Union.[63] |

|||

The global digital divide describes global disparities, primarily between developed and developing countries, in regards to access to computing and information resources such as the Internet and the opportunities derived from such access.[65] As with a smaller unit of analysis, this gap describes an inequality that exists, referencing a global scale.

The Internet is expanding very quickly, and not all countries—especially developing countries—are able to keep up with the constant changes. The term “digital divide” doesn’t necessarily mean that someone doesn’t have technology; it could mean that there is simply a difference in technology. These differences can refer to, for example, high-quality computers, fast Internet, technical assistance, or telephone services. The difference between all of these is also considered a gap.

In fact, there is a large inequality worldwide in terms of the distribution of installed telecommunication bandwidth. In 2014 only 3 countries (China, US, Japan) host 50% of the globally installed bandwidth potential (see pie-chart Figure on the right).[13] This concentration is not new, as historically only 10 countries have hosted 70–75% of the global telecommunication capacity (see Figure). The U.S. lost its global leadership in terms of installed bandwidth in 2011, being replaced by China, which hosts more than twice as much national bandwidth potential in 2014 (29% versus 13% of the global total).[13]

Versus the digital divide

The global digital divide is a special case of the digital divide, the focus is set on the fact that “Internet has developed unevenly throughout the world”[33]:681 causing some countries to fall behind in technology, education, labor, democracy, and tourism. The concept of the digital divide was originally popularized in regard to the disparity in Internet access between rural and urban areas of the United States of America; the global digital divide mirrors this disparity on an international scale.

The global digital divide also contributes to the inequality of access to goods and services available through technology. Computers and the Internet provide users with improved education, which can lead to higher wages; the people living in nations with limited access are therefore disadvantaged.[66] This global divide is often characterized as falling along what is sometimes called thenorth-south divide of “northern” wealthier nations and “southern” poorer ones.