11.2 – Calcium

Learning Objective

- Discuss the roles of calcium in the body

- Describe the risks associated with deficiency or toxicity of calcium.

- List food groups that are dietary sources of calcium.

Calcium’s Functional Roles

Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the body and greater than 99 percent of it is stored in bone tissue. Although only 1 percent of the calcium in the human body is found in the blood and soft tissues, it is here that it performs the most critical functions. Blood calcium levels are rigorously controlled so that if blood levels drop the body will rapidly respond by stimulating bone breakdown, thereby releasing stored calcium into the blood. Thus, bone tissue sacrifices its stored calcium to maintain blood calcium levels. This is why bone health is dependent on the intake of dietary calcium and also why blood levels of calcium do not always correspond to dietary intake.

Calcium plays a role in a number of different functions in the body like bone and tooth formation. The most well-known calcium function is to build and strengthen bones and teeth. Recall that when bone tissue first forms during the modeling or remodeling process, it is unhardened, protein-rich tissue. In the process of bone mineralization, calcium phosphates (salts) are deposited on the protein matrix. The calcium salts typically make up about 65 percent of bone tissue. When your diet is calcium deficient, the mineral content of bone decreases causing it to become brittle and weak. Thus, increased calcium intake helps to increase the mineralized content of bone tissue. Greater mineralized bone tissue corresponds to a greater bone mineral density (BMD), and to greater bone strength. The remaining calcium plays a role in nerve impulse transmission by facilitating electrical impulse transmission from one nerve cell to another. Calcium in muscle cells is essential for muscle contraction because the flow of calcium ions are needed for the muscle proteins to interact. Calcium is also essential in blood clotting by activating clotting factors to fix damaged tissue.

In addition to calcium’s four primary functions calcium has several other minor functions that are also critical for maintaining normal physiology. For example, without calcium, the hormone insulin could not be released from cells in the pancreas and glycogen could not be broken down in muscle cells and used to provide energy for muscle contraction.

Maintaining Calcium Levels

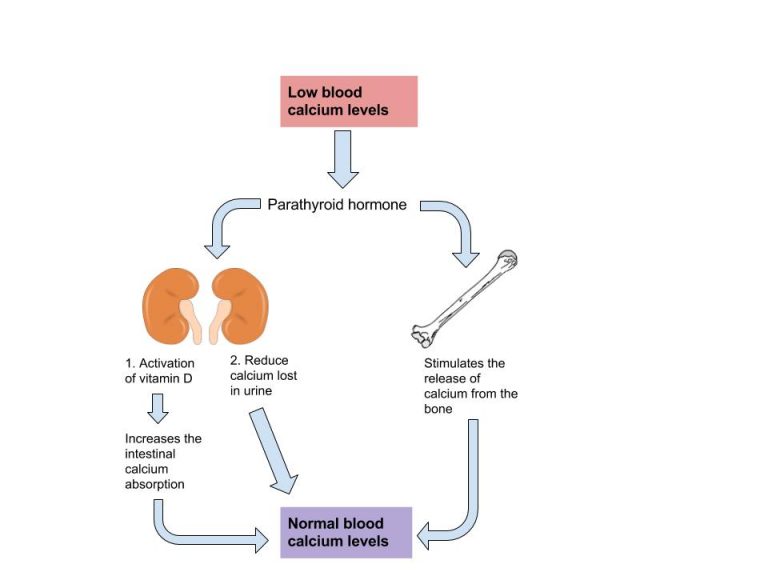

Because calcium performs such vital functions in the body, blood calcium level is closely regulated by the hormones parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcitriol, and calcitonin. When blood calcium levels are low, PTH is secreted to increase blood calcium levels via three different mechanisms. First, PTH stimulates the release of calcium stored in the bone. Second, PTH acts on kidney cells to increase calcium reabsorption and decrease its excretion in the urine. Third, PTH stimulates enzymes in the kidney that activate vitamin D to calcitriol. Calcitriol is the active hormone that acts on the intestinal cells and increases dietary calcium absorption. When blood calcium levels become too high, the hormone calcitonin is secreted by certain cells in the thyroid gland and PTH secretion stops. At higher nonphysiological concentrations, calcitonin lowers blood calcium levels by increasing calcium excretion in the urine, preventing further absorption of calcium in the gut and by directly inhibiting bone resorption.

Other Health Benefits of Calcium in the Body

Besides forming and maintaining strong bones and teeth, calcium has been shown to have other health benefits for the body, including:

- Cancer. The National Cancer Institute reports that there is enough scientific evidence to conclude that higher intakes of calcium decrease colon cancer risk and may suppress the growth of polyps that often precipitate cancer. Although higher calcium consumption protects against colon cancer, some studies have looked at the relationship between calcium and prostate cancer and found higher intakes may increase the risk for prostate cancer; however, the data is inconsistent and more studies are needed to confirm any negative association.

- Blood pressure. Multiple studies provide clear evidence that higher calcium consumption reduces blood pressure. A review of twenty-three observational studies concluded that for every 100 milligrams of calcium consumed daily, systolic blood pressure is reduced 0.34 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure is decreased by 0.15 mmHg.1

- Kidney stones. Another health benefit of a high-calcium diet is that it blocks kidney stone formation. Note that this benefit refers to diet, not supplements. Calcium inhibits the absorption of oxalate, a chemical in plants such as parsley and spinach, which is associated with an increased risk for developing kidney stones. Calcium’s protective effects on kidney stone formation occur only when you obtain calcium from dietary sources. Calcium supplements may actually increase the risk of kidney stones in susceptible people.

Calcium inadequacy is prevalent in adolescent girls and the elderly. Proper dietary intake of calcium is critical for proper bone health.

Despite the wealth of evidence supporting the many health benefits of calcium (particularly bone health), the average American diet falls short of achieving the recommended dietary intakes of calcium. In fact, in females older than nine years of age, the average daily intake of calcium is only about 70 percent of the recommended intake. Here we will take a closer look at particular groups of people who may require extra calcium intake.

- Adolescent teens. A calcium-deficient diet is common in teenage girls as their dairy consumption often considerably drops during adolescence.

- Amenorrheic women. Amenorrhea refers to the absence of a menstrual cycle. Women who fail to menstruate suffer from reduced estrogen levels, which can disrupt and have a negative impact on the calcium balance in their bodies. Exercise-induced amenorrhea and anorexia nervosa-related amenorrhea can decrease bone mass.2,3 In female athletes, as well as active women in the military, low BMD, menstrual irregularities, and individual dietary habits together with a history of previous stress issues are related to an increased susceptibility to future stress fractures.4,5

- The elderly. As people age, calcium bioavailability is reduced, the kidneys lose their capacity to convert vitamin D to its most active form, the kidneys are no longer efficient in retaining calcium, the skin is less effective at synthesizing vitamin D, there are changes in overall dietary patterns, and older people tend to get less exposure to sunlight. Thus the risk for calcium inadequacy and bone loss is great.6

- Postmenopausal women. Estrogen enhances calcium absorption. The decline in this hormone during and after menopause puts postmenopausal women especially at risk for calcium deficiency. Decreases in estrogen production are responsible for an increase in bone resorption and a decrease in calcium absorption. During the first years of menopause, annual decreases in bone mass range from 3–5 percent. After age sixty-five, decreases are typically less than 1 percent.7

- Lactose-intolerant people. Groups of people, such as those who are lactose intolerant, or who adhere to diets that avoid dairy products, may not have an adequate calcium intake.

- Vegans. Vegans typically absorb reduced amounts of calcium because their diets favor plant-based foods that contain oxalates and phytates.8

In addition, because vegans avoid dairy products, their overall consumption of calcium-rich foods may be less.

If you are lactose intolerant, have a milk allergy, are a vegan, or you simply do not like dairy products, remember that there are many plant-based foods that have a good amount of calcium and there are also some low-lactose and lactose-free dairy products on the market.

1 Birkett NJ. Comments on a Meta-Analysis of the Relation between Dietary Calcium Intake and Blood Pressure. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(3), 223–28. http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/148/3/223.long. Accessed June 30, 2019.

2 Marcus R. et al. Menstrual Function and Bone Mass in Elite Women Distance Runners: Endocrine and Metabolic Features. Ann Intern Med.

1985; 102(2), 58–63. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3966752?dopt=Abstract. Accessed June 30, 2019

3 Nattiv A. Stress Fractures and Bone Health in Track and Field Athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2000; 3(3), 268–79. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11101266?dopt=Abstract. Accessed June 30, 2019

4 Johnson AO, et al. Correlation of Lactose Maldigestion, Lactose Intolerance, and Milk Intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993; 57(3), 399–401. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8438774?dopt=Abstract. Accessed June 30, 2019

5 Calcium and Vitamin D in the Elderly. International Osteoporosis Foundation. http://www.iofbonehealth.org/patients-public/about-osteoporosis/prevention/nutrition/calcium-and-vitamin-d-in-the-elderly.html. Published 2012. Accessed June 30, 2019

6 Osteoporosis Overview. NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center. Updated October 2018. Accessed June 30, 2019

7 Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D.Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 2010.

osteoporosis

There are several factors that lead to loss of bone quality during aging, including a reduction in hormone levels, decreased calcium absorption, and increased muscle deterioration. It is comparable to being charged with the task of maintaining and repairing the structure of your home without having all of the necessary materials to do so. However, you will learn that there are many ways to maximize your bone health at any age.

Osteoporosis is the excessive loss of bone over time. It leads to decreased bone strength and increased susceptibility to bone fracture. Sozen et al. wrote in the European j of Rheumatology that “currently, it has been estimated that more than 200 million people are suffering from osteoporosis. According to recent statistics from the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOG), worldwide, 1 in 3 women over the age of 50 years and 1 in 5 men will experience osteoporotic fractures in their lifetime.” 1 Osteoporosis is a debilitating disease that markedly increases the risks of suffering from bone fractures. A fracture in the hip causes the most serious consequences—and approximately 20 percent of senior citizens who have one will die in the year after the injury. These statistics may appear grim, but many organizations—including the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the IOF—are disseminating information to the public and to health-care professionals on ways to prevent the disease, while at the same time, science is advancing in the prevention and treatment of this disease.

As previously discussed, bones grow and mineralize predominately during infancy, childhood, and puberty. During this time, bone growth exceeds bone loss. By age twenty, bone growth is fairly complete and only a small amount (about 10 percent) of bone mass accumulates in the third decade of life. By age thirty, bone mass is at its greatest in both men and women and then gradually declines after age forty. Bone mass refers to the total weight of bone tissue in the human body. The greatest quantity of bone tissue a person develops during his or her lifetime is called peak bone mass. The decline in bone mass after age forty occurs because bone loss is greater than bone growth.

Osteoporosis is referred to as a silent disease, much like high blood pressure, because symptoms are rarely exhibited. A person with osteoporosis may not know he has the disease until he experiences a bone break or fracture. Detection and treatment of osteoporosis, before the occurrence of a fracture, can significantly improve the quality of life. To detect osteopenia or osteoporosis, BMD must be measured by the DEXA procedure.

Osteoporosis is categorized into two types that differ by the age of onset and what type of bone tissue is most severely deteriorated. Type 1 osteoporosis, also called postmenopausal osteoporosis, most often develops in women between the ages of fifty and seventy. Between the ages of forty-five and fifty, women go through menopause and their ovaries stop producing estrogen. Because estrogen plays a role in maintaining bone mass, its rapid decline during menopause accelerates bone loss. This occurs mainly as a result of increased osteoclast activity. The trabecular tissue is more severely affected because it contains more osteoclasts cells than cortical tissue. Type 1 osteoporosis is commonly characterized by wrist and spine fractures. Type 2 osteoporosis is also called senile osteoporosis and typically occurs after the age of seventy. It affects women twice as much as men and is most often associated with hip and spine fractures. In Type 2 osteoporosis, both the trabecular and cortical bone tissues are significantly affected. Not everybody develops osteoporosis as they age. Other factors also contribute to the risk or likelihood of developing the disease.

Figure 11.2.3: Osteoporosis in Vertebrae. Osteoporosis is characterized by a gradual weakening of the bones, which leads to poor skeletal formation. (CC BY-SA 3.0)– Own work

During the course of both types of osteoporosis, BMD decreases and the bone tissue microarchitecture is compromised. Excessive bone resorption in the trabecular tissue increases the size of the holes in the lattice-like structure making it more porous and weaker. A disproportionate amount of resorption of the strong cortical bone causes it to become thinner. The deterioration of one or both types of bone tissue causes bones to weaken and, consequently, become more susceptible to fractures.

When the vertebral bone tissue is weakened, it can cause the spine to begin to curve (Figure 11.2.3). The increase in spine curvature not only causes pain but also decreases a person’s height. The curvature of the upper spine produces what is called Dowager’s hump, also known as kyphosis. The severe upper-spine deformity can compress the chest cavity and cause difficulty breathing. It may also cause abdominal pain and loss of appetite because of the increased pressure on the abdomen.

1 Sözen T, Özışık L, Başaran NÇ. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017;4(1):46–56. DOI:10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048

Calcium Supplements: Which One to Buy

Many people choose to fulfill their daily calcium requirements by taking calcium supplements. Calcium supplements are sold primarily as calcium carbonate, calcium citrate, calcium lactate, and calcium phosphate, with elemental calcium contents of about 200 milligrams per pill. It is important to note that calcium carbonate requires an acidic environment in the stomach to be used effectively. Although this is not a problem for most people, it may be for those on medication to reduce stomach-acid production or for the elderly who may have a reduced ability to secrete acid in the stomach. For these people, calcium citrate may be a better choice. Otherwise, calcium carbonate is the cheapest. The body is capable of absorbing approximately 30 percent of the calcium from these forms.

Beware of Lead

There is public health concern about the lead content of some brands of calcium supplements, as supplements derived from natural sources such as oyster shell, bone meal, and dolomite (a type of rock containing calcium magnesium carbonate) are known to contain high amounts of lead. In one study conducted on twenty-two brands of calcium supplements, it was proven that eight of the brands exceeded the acceptable limit for lead content. This was found to be the case in supplements derived from oyster shell and refined calcium carbonate. The same study also found that brands claiming to be lead-free did, in fact, show very low lead levels. Because lead levels in supplements are not disclosed on labels, it is important to know that products not derived from an oyster shell or other natural substances are generally low in lead content. In addition, it was also found that one brand did not disintegrate as is necessary for absorption, and one brand contained only 77 percent of the stated calcium content.8

8 Ross EA, Szabo NJ, Tebbett IR. Lead Content of Calcium Supplements. JAMA. 2000; 284, 1425–33.Accessed June 30, 2019.

Diet, Supplements, and Chelated Supplements

In general, calcium supplements perform to a lesser degree than dietary sources of calcium in providing many of the health benefits linked to higher calcium intake. This is partly attributed to the fact that dietary sources of calcium supply additional nutrients with health-promoting activities. It is reported that chelated forms of calcium supplements are easier to absorb as the chelation process protects the calcium from oxalates and phytates that may bind with the calcium in the intestines. However, these are more expensive supplements and only increase calcium absorption up to 10 percent. In people with low dietary intakes of calcium, calcium supplements have a negligible benefit on bone health in the absence of vitamin D. Remember that vitamin D has to be activated and in the bloodstream to promote calcium absorption. Thus, it is important to maintain an adequate intake of vitamin D. It is best to limit calcium supplementation to less than 500 mg per day and strive to get most of your calcium from food.

The Calcium Debate

A recent study published in the British Medical Journal reported that people who take calcium supplements at doses equal to or greater than 500 milligrams per day in the absence of a vitamin D supplement had a 30 percent greater risk for having a heart attack.9

Does this mean that calcium supplements are bad for you? If you look more closely at the study, you will find that 5.8 percent of people (143 people) who took calcium supplements had a heart attack, but so did 5.5 percent of the people (111) people who took the placebo. While this is one study, several other large studies have not shown that calcium supplementation increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. While the debate over this continues, we should focus on the things we do know:

- There is overwhelming evidence that diets sufficient in calcium prevent osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.

- People with risk factors for osteoporosis are advised to take calcium supplements if they are unable to get enough calcium in their diet. The National Osteoporosis Foundation advises that adults age fifty and above consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium per day. This includes calcium both from dietary sources and supplements.

- Consuming more calcium than is recommended is not better for your health and can prove to be detrimental. Consuming too much calcium at any one time, be it from diet or supplements, impairs not only the absorption of calcium itself but also the absorption of other essential minerals, such as iron and zinc. Since the GI tract can only handle about 500 milligrams of calcium at one time, it is recommended to have split doses of calcium supplements rather than taking a few all at once to get the R.D.A. of calcium.

9 Bolland MJ. et al. Effect of Calcium Supplements on Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Cardiovascular Events: Meta-Analysis. Br Med J. 2010; 341(c3691).

Dietary Reference Intake for Calcium

The recommended dietary allowances (R.D.A.) for calcium are listed in Table 10.2.1. The R.D.A. is elevated to 1,300 milligrams per day during adolescence because this is the life stage with accelerated bone growth. Studies have shown that a higher intake of calcium during puberty increases the total amount of bone tissue that accumulates in a person. For women above age fifty and men older than seventy-one, the R.D.A.s are also a bit higher for several reasons including that as we age, calcium absorption in the gut decreases, vitamin D3 activation is reduced, and maintaining adequate blood levels of calcium is important to prevent an acceleration of bone tissue loss (especially during menopause). Currently, the dietary intake of calcium for females above age nine is, on average, below the R.D.A. for calcium. The Institute of Medicine (I.O.M.) recommends that people do not consume over 2,500 milligrams per day of calcium as it may cause adverse effects in some people.

| Age Group | R.D.A. (milligrams per day) | U.L. (milligrams per day) |

|---|---|---|

| Infants (0–6 months) | 200* | None |

| Infants (6–12 months) | 260* | None |

| Children (1–3 years) | 700 | 2,500 |

| Children (4–8 years) | 1,000 | 2,500 |

| Children (9–13 years) | 1,300 | 2,500 |

| Adolescents (14–18 years) | 1,300 | 2,500 |

| Adults (19–50 years) | 1,000 | 2,500 |

| Adult females (50–71 years) | 1,200 | 2,500 |

| Adults, male & female (> 71 years) | 1,200 | 2,500 |

Denotes Adequate Intake

Source: Ross AC, Manson JE, et al. The 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What Clinicians Need to Know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011; 96(1), 53–8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21118827. Accessed June 30, 2019.

Dietary Sources of Calcium

In the typical American diet, calcium is obtained mostly from dairy products, primarily cheese. A slice of cheddar or Swiss cheese contains just over 200 milligrams of calcium. One cup of nonfat milk contains approximately 300 milligrams of calcium, which is about a third of the R.D.A. for calcium for most adults. Foods fortified with calcium such as cereals, soy milk, and orange juice also provide one third or greater of the calcium R.D.A.. Although the typical American diet relies mostly on dairy products for obtaining calcium, there are other good non-dairy sources of calcium.

Tools For Change

If you need to increase calcium intake, are a vegan, or have a food allergy to dairy products, it is helpful to know that there are some plant-based foods that are high in calcium. Tofu (made with calcium sulfate), turnip greens, mustard greens, and Chinese cabbage are good sources. For a list of non-dairy sources, you can find the calcium content for thousands of foods by visiting the USDA National Nutrient Database. When obtaining your calcium from a vegan diet, it is important to know that some plant-based foods significantly impair the absorption of calcium. These include spinach, Swiss chard, rhubarb, beets, cashews, and peanuts. With careful planning and good selections, you can ensure that you are getting enough calcium in your diet even if you do not drink milk or consume other dairy products.

Table 11.2.2: Calcium Content of Various Foods

| Food | Serving | Calcium (milligrams) | Percent Daily Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yogurt, low fat | 8 oz. | 415 | 42 |

| Mozzarella | 1.5 oz. | 333 | 33 |

| Sardines, canned with bones | 3 oz. | 325 | 33 |

| Cheddar Cheese | 1.5 oz. | 307 | 31 |

| Milk, nonfat | 8 oz. | 299 | 30 |

| Soymilk, calcium-fortified | 8 oz. | 299 | 30 |

| Orange juice, calcium-fortified | 6 oz. | 261 | 26 |

| Tofu, firm, made with calcium sulfate | ½ c. | 253 | 25 |

| Salmon, canned with bones | 3 oz. | 181 | 18 |

| Turnip, boiled | ½ c. | 99 | 10 |

| Kale, cooked | 1 c. | 94 | 9 |

| Vanilla Ice Cream | ½ c. | 84 | 8 |

| White bread | 1 slice | 73 | 7 |

| Kale, raw | 1 c. | 24 | 2 |

| Broccoli, raw | ½ c. | 21 | 2 |

Source: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals: Calcium. National Institute of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/. Updated September 26, 2018. Accessed June 30, 2019.

Calcium Bioavailability

In the small intestine, calcium absorption primarily takes place in the duodenum (first section of the small intestine) when intakes are low, but calcium is also absorbed passively in the jejunum and ileum (second and third sections of the small intestine), especially when intakes are higher. The body doesn’t completely absorb all the calcium in food. Interestingly, the calcium in some vegetables such as kale, Brussel sprouts, and bok choy is better absorbed by the body than are dairy products. About 30 percent of calcium is absorbed from milk and other dairy products.

The greatest positive influence on calcium absorption comes from having an adequate intake of vitamin D. People deficient in vitamin D absorb less than 15 percent of calcium from the foods they eat. The hormone estrogen is another factor that enhances calcium bioavailability. Thus, as a woman ages and goes through menopause, during which estrogen levels fall, the amount of calcium absorbed decreases and the risk for bone disease increases. Some fibers, such as inulin, found in jicama, onions, and garlic, also promote calcium intestinal uptake.

Chemicals that bind to calcium decrease its bioavailability. Substances with a negative effect on the bioavailability of calcium absorption include the oxalates in certain plants, the tannins in tea, phytates in nuts, seeds, and grains, and some fibers. Oxalates are found in high concentrations in spinach, parsley, cocoa, and beets. In general, the calcium bioavailability is inversely correlated to the oxalate content in foods. High-fiber, low-fat diets also decrease the amount of calcium absorbed, an effect likely related to how fiber and fat influence the amount of time food stays in the gut. Anything that causes diarrhea, including sickness, medications, and certain symptoms related to old age, decreases the transit time of calcium in the gut and therefore decreases calcium absorption. As we get older, stomach acidity sometimes decreases, diarrhea occurs more often, kidney function is impaired, and vitamin D absorption and activation are compromised, all of which contribute to a decrease in calcium bioavailability.

Key Takeaways

- The most well-known role of calcium is to build and strengthen bones and teeth.

- Calcium plays a role in nerve impulse transmission by facilitating electrical impulse transmission from one nerve cell to another.

- Calcium in muscle cells is essential for muscle contraction because the flow of calcium ions are needed for the muscle proteins to interact.

- Calcium is also essential in blood clotting by activating clotting factors to fix damaged tissue.

- In addition to calcium’s four primary functions calcium has several other minor functions that are also critical for maintaining normal physiology. Without calcium, the hormone insulin could not be released from cells in the pancreas and glycogen could not be broken down in muscle cells and used to provide energy for muscle contraction.

- Proper dietary intake of calcium is critical for proper bone health. Calcium inadequacy is prevalent in adolescent girls and the elderly.

- Describe the risks associated with deficiency or toxicity of calcium.

- List food groups that are dietary sources of calcium.

- Bone mineral density (BMD) is an indicator of bone quality and correlates with bone strength.

- Excessive bone loss can lead to the development of osteopenia and eventually osteoporosis. Osteoporosis affects women more than men but is a debilitating disease for either sex. Osteoporosis is often a silent disease that doesn’t manifest itself until a fracture is sustained.

- Consuming more calcium than is recommended is not better for your health and can prove to be detrimental. If you take a calcium supplement, take 500 mg or less at one time.

Contributors

University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program: Allison Calabrese, Cheryl Gibby, Billy Meinke, Marie Kainoa Fialkowski Revilla, and Alan Titchenal