9.1 Traditional Overhead Allocation

Barry thinks of his education as a job and spends forty hours a week in class or studying. Barry estimates he has about eighty hours per week to allocate between school and other activities and believes everyone should follow his fifty-fifty rule of time allocation. His roommate, Kamil, disagrees with Barry and argues that allocating 50 percent of one’s time to class and studying is not a great formula because everyone has different activities and responsibilities. Kamil points out, for example, that he has a job tutoring other students, is involved with student activities, and plays in a band, while Barry spends some of his nonstudy time doing volunteer work and working out.

Kamil plans each week based on how many hours he will need for each activity: classes, studying and coursework, tutoring, and practicing and performing with his band. In essence, he considers the details of each week’s needs to budget his time. Kamil explains to Barry that being aware of the activities that consume his limited resources (time, in this example) helps him to better plan his week. He adds that individuals who have activities with lots of time commitments (class, work, study, exercise, family, friends, and so on) must be efficient with their time or they risk doing poorly in one or more areas. Kamil argues these individuals cannot simply assign a percentage of their time to each activity but should use each specific activity as the basis for allocating their time. Barry insists that assigning a set percentage to everything is easy and the better method. Who is correct?

Both roommates make valid points about allocating limited resources. Ultimately, each must decide which method to use to allocate time, and they can make that decision based on their own analyses. Similarly, businesses and other organizations must create an allocation system for assigning limited resources, such as overhead. Whereas Kamil and Barry are discussing the allocation of hours, the issue of allocating costs raises similar questions. For example, for a manufacturer allocating maintenance costs, which are an overhead cost, is it better to allocate to each production department equally by the number of machines that need to be maintained or by the square footage of space that needs to be maintained?

In the past, overhead costs were typically allocated based on factors such as total direct labor hours, total direct labor costs, or total machine hours. This allocation process, often called the traditional allocation method, works most effectively when direct labor is a dominant component in production. However, many industries have evolved, primarily due to changes in technology, and their production processes have become more complicated, with more steps or components. Many of these industries have significantly reduced their use of direct labor and replaced it with technology, such as robotics or other machinery. For example, a mobile phone production facility in China replaced 90 percent of its workforce with robots.1

In these situations, a direct cost (labor) has been replaced by an overhead cost (e.g., depreciation on equipment). Because of this decrease in reliance on labor and/or changes in the types of production complexity and methods, the traditional method of overhead allocation becomes less effective in certain production environments. To account for these changes in technology and production, many organizations today have adopted an overhead allocation method known as activity-based costing (ABC). This chapter will explain the transition to ABC and provide a foundation in its mechanics.

Activity-based costing is an accounting method that recognizes the relationship between product costs and a production activity, such as the number of hours of engineering or design activity, the costs of the set up or preparation for the production of different products, or the costs of packaging different products after the production process is completed. Overhead costs are then allocated to production according to the use of that activity, such as the number of machine setups needed. In contrast, the traditional allocation method commonly uses cost drivers, such as direct labor or machine hours, as the single activity.

Because of the use of multiple activities as cost drivers, ABC costing has advantages over the traditional allocation method, which assigns overhead using a single predetermined overhead rate. Those advantages come at a cost, both in resources and time, since additional information needs to be collected and analyzed. Chrysler, for instance, shifted its overhead allocation to ABC in 1991 and estimates that the benefits of cost savings, product improvement, and elimination of inefficiencies have been ten to twenty times greater than the investment in the program at some sites. It believes other sites experienced savings of fifty to one hundred times the cost to implement the system.2

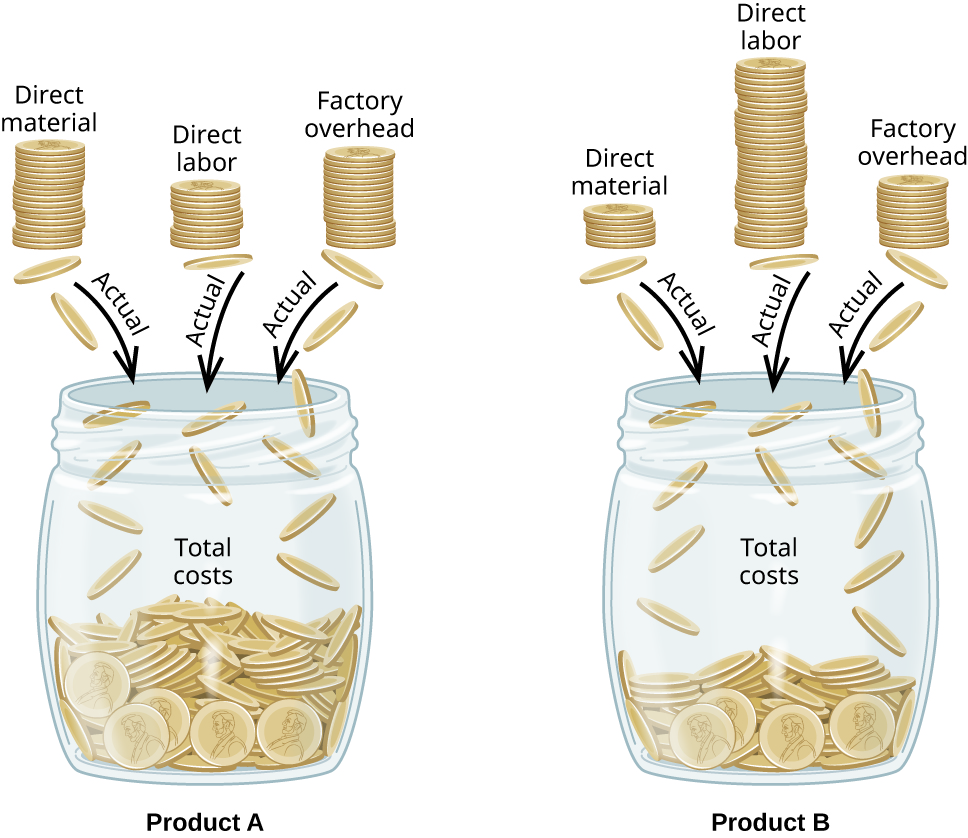

As you’ve learned, understanding the cost needed to manufacture a product is critical to making many management decisions (Figure 9.1). Knowing the total and component costs of the product is necessary for price setting and for measuring the efficiency and effectiveness of the organization. Remember that product costs consist of direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead. It is relatively simple to understand each product’s direct material and direct labor cost, but it is more complicated to determine the overhead component of each product’s costs because there are a number of indirect and other costs to consider. A company’s manufacturing overhead costs are all costs other than direct material, direct labor, or selling and administrative costs. Once a company has determined the overhead, it must establish how to allocate the cost. This allocation can come in the form of the traditional overhead allocation method or activity-based costing..

Component Categories under Traditional Allocation

Traditional allocation involves the allocation of factory overhead to products based on the volume of production resources consumed, such as the amount of direct labor hours consumed, direct labor cost, or machine hours used. In order to perform the traditional method, it is also important to understand each of the involved cost components: direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead. Direct materials and direct labor are cost categories that are relatively easy to trace to a product. Direct material comprises the supplies used in manufacturing that can be traced directly to the product. Direct labor is the work used in manufacturing that can be directly traced to the product. Although the processes for tracing the costs differ, both job order costing and process costing trace the material and labor through materials requisition requests and time cards or electronic mechanisms for measuring labor input. Job order costing traces the costs directly to the product, and process costing traces the costs to the manufacturing department.

Estimated Total Manufacturing Overhead Costs

The more challenging product component to track is manufacturing overhead. Overhead consists of indirect materials, indirect labor, and other costs closely associated with the manufacturing process but not tied to a specific product. Examples of other overhead costs include such items as depreciation on the factory machinery and insurance on the factory building. Indirect material comprises the supplies used in production that cannot be traced to an individual product, and indirect labor is the work done by employees not directly involved in the manufacturing process, such as the supervisors’ salaries or the maintenance staff’s wages. Because these costs cannot be traced directly to the product like direct costs are, they have to be allocated among all of the products produced and added, or applied, to the production and product cost.

For example, the recipe for shea butter has easily identifiable quantities of shea nuts and other ingredients. Based on the manufacturing process, it is also easy to determine the direct labor cost. But determining the exact overhead costs is not easy, as the cost of electricity needed to dry, crush, and roast the nuts changes depending on the moisture content of the nuts upon arrival.

Until now, you have learned to apply overhead to production based on a predetermined overhead rate typically using an activity base. An activity base is considered to be a primary driver of overhead costs, and traditionally, direct labor hours or machine hours were used for it. For example, a production facility that is fairly labor intensive would likely determine that the more labor hours worked, the higher the overhead will be. As a result, management would likely view labor hours as the activity base when applying overhead costs.

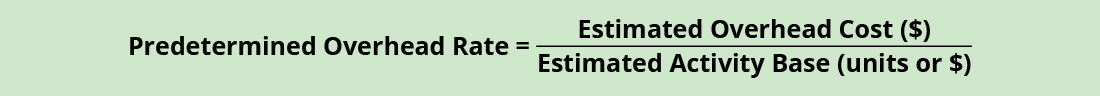

A predetermined overhead rate is calculated at the start of the accounting period by dividing the estimated manufacturing overhead by the estimated activity base. The predetermined overhead rate is then applied to production to facilitate determining a standard cost for a product. This estimated overhead rate will allow a company to determine a cost for the product without having to wait, possibly several months, until all of the actual overhead costs are determined, and to help with issues such as seasonal production or variable overhead costs, such as utilities.

Calculation of Predetermined Overhead and Total Cost under Traditional Allocation

The predetermined overhead rate is set at the beginning of the year and is calculated as the estimated (budgeted) overhead costs for the year divided by the estimated (budgeted) level of activity for the year. This activity base is often direct labor hours, direct labor costs, or machine hours. Once a company determines the overhead rate, it determines the overhead rate per unit and adds the overhead per unit cost to the direct material and direct labor costs for the product to find the total cost.

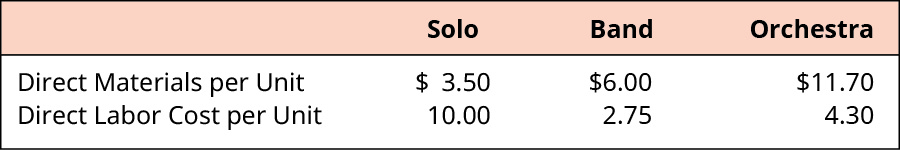

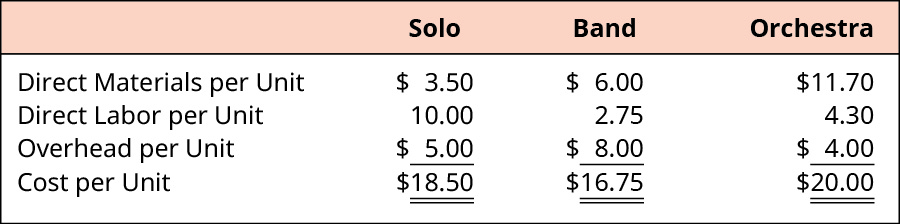

To put this method into context, consider this example. Musicality Manufacturing developed a recording device similar to a microphone that allows musicians and music aficionados to record their playing or singing along with any song publicly available. There are three products that vary in features and ability: Solo, Band, and Orchestra. Musicality was started by musicians who majored in math and software engineering while in college. Their main concern was building a quality manufacturing plant, so they used the simpler traditional allocation method. They started by determining their direct costs, which are shown in Figure 9.3.

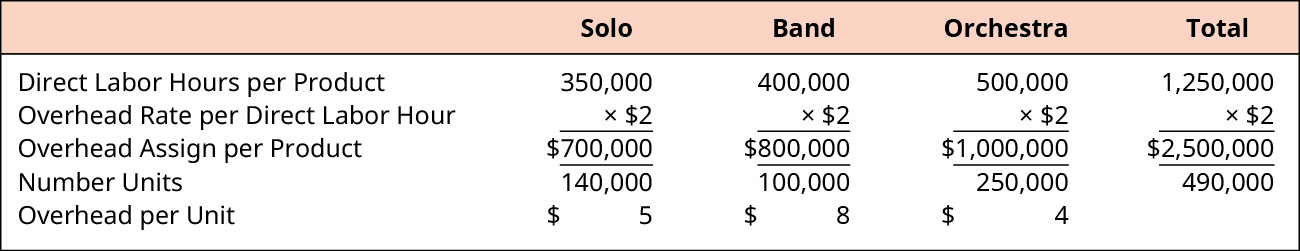

Musicality determines the overhead rate based on direct labor hours. At the beginning of the year, the company estimates total overhead costs to be $2,500,000 and total direct labor hours to be 1,250,000. The predetermined overhead rate is

Musicality uses this information to determine the cost of each product. For example, the total direct labor hours estimated for the solo product is 350,000 direct labor hours. With $2.00 of overhead per direct hour, the Solo product is estimated to have $700,000 of overhead applied. When the $700,000 of overhead applied is divided by the estimated production of 140,000 units of the Solo product, the estimated overhead per product for the Solo product is $5.00 per unit. The computation of the overhead cost per unit for all of the products is shown in Figure 9.4.

The overhead cost per unit from Figure 9.4 is combined with the direct material and direct labor costs as shown in Figure 9.3 to compute the total cost per unit as shown in Figure 9.5.

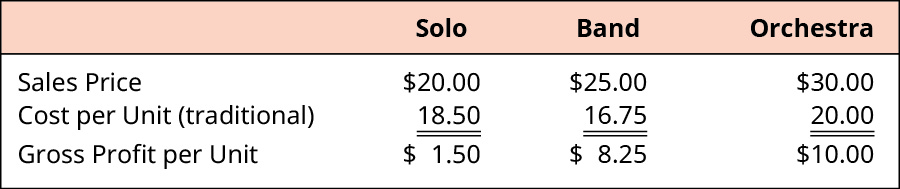

After reviewing the product cost and consulting with the marketing department, the sales prices were set. The sales price, cost of each product, and resulting gross profit are shown in Figure 9.6.

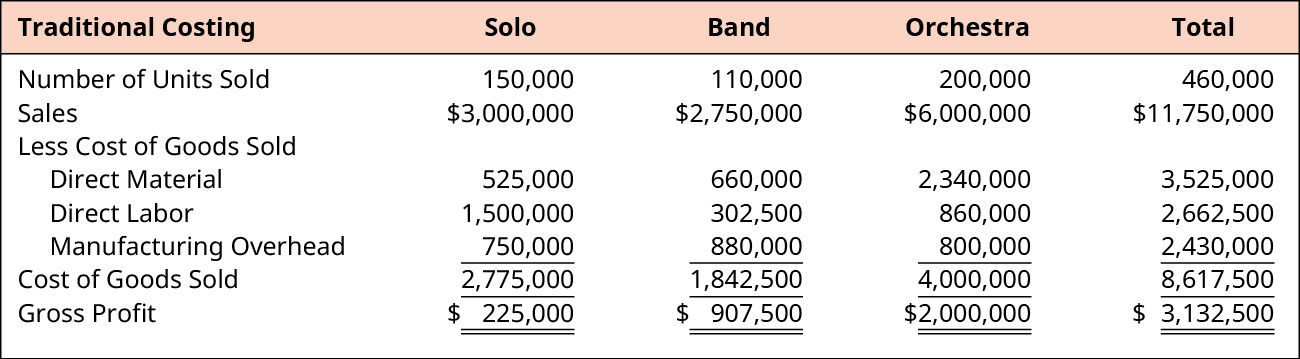

Sales of each product have been strong, and the total gross profit for each product is shown in Figure 9.7. Using the Solo product as an example, 150,000 units are sold at a price of $20 per unit resulting in sales of $3,000,000. The cost of goods sold consists of direct materials of $3.50 per unit, direct labor of $10 per unit, and manufacturing overhead of $5.00 per unit. With 150,000 units, the direct material cost is $525,000; the direct labor cost is $1,500,000; and the manufacturing overhead applied is $750,000 for a total Cost of Goods Sold of $2,775,000. The resulting Gross Profit is $225,000 or $1.50 per unit.

Long Descriptions

Computation of overhead per unit for Solo, Band, Orchestra, and total, respectively. Direct Labor Hours per Product: 350,000, 400,000, 500,000, 1,250,000. Times Overhead Rate per Direct Labor Hour: $2.00 for all columns. Equals Overhead Assigned per Product: $700,000, $800,000, $1,000,000, $2,500,000. Divide by the Number of Units: 140,000, 100,000, 250,000, 490,000. Equals Overhead per Unit: $5, $8, $4. Return

Calculation of Total Gross Profit for Solo, Band, Orchestra, and Total, respectively. Number of Units Sold: 150,000, 110,000, 200,000, 460,000. Sales: $3,000,000, $2,750,000, $6,000,000, $11,750,000. Less Cost of Goods Sold. Direct Material: 525,000, 660,000, 2,340,000, 3,525,000. Direct Labor: 1,500,000, 302,500, 860,000, 2,662,500. Manufacturing Overhead: 750,000, 880,000, 800,000, 2,430,000. Cost of Goods Sold: 2,775,000, 1,842,500, 4,000,000, 8,617,500. Gross Profit: $225,000, $907,500, $2,000,000, $3,132,500. Return

Footnotes

- 1 June Javelosa and Kristin Houser. “This Company Replaced 90% of Its Workforce with Machines. Here’s What Happened.” Futurism / World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/02/after-replacing-90-of-employees-with-robots-this-companys-productivity-soared

- 2 Joseph H. Ness and Thomas G. Cucuzza. “Tapping the Full Potential of ABC.” Harvard Business Review. July-Aug. 1995. https://hbr.org/1995/07/tapping-the-full-potential-of-abc