1.8 The Accounting Cycle

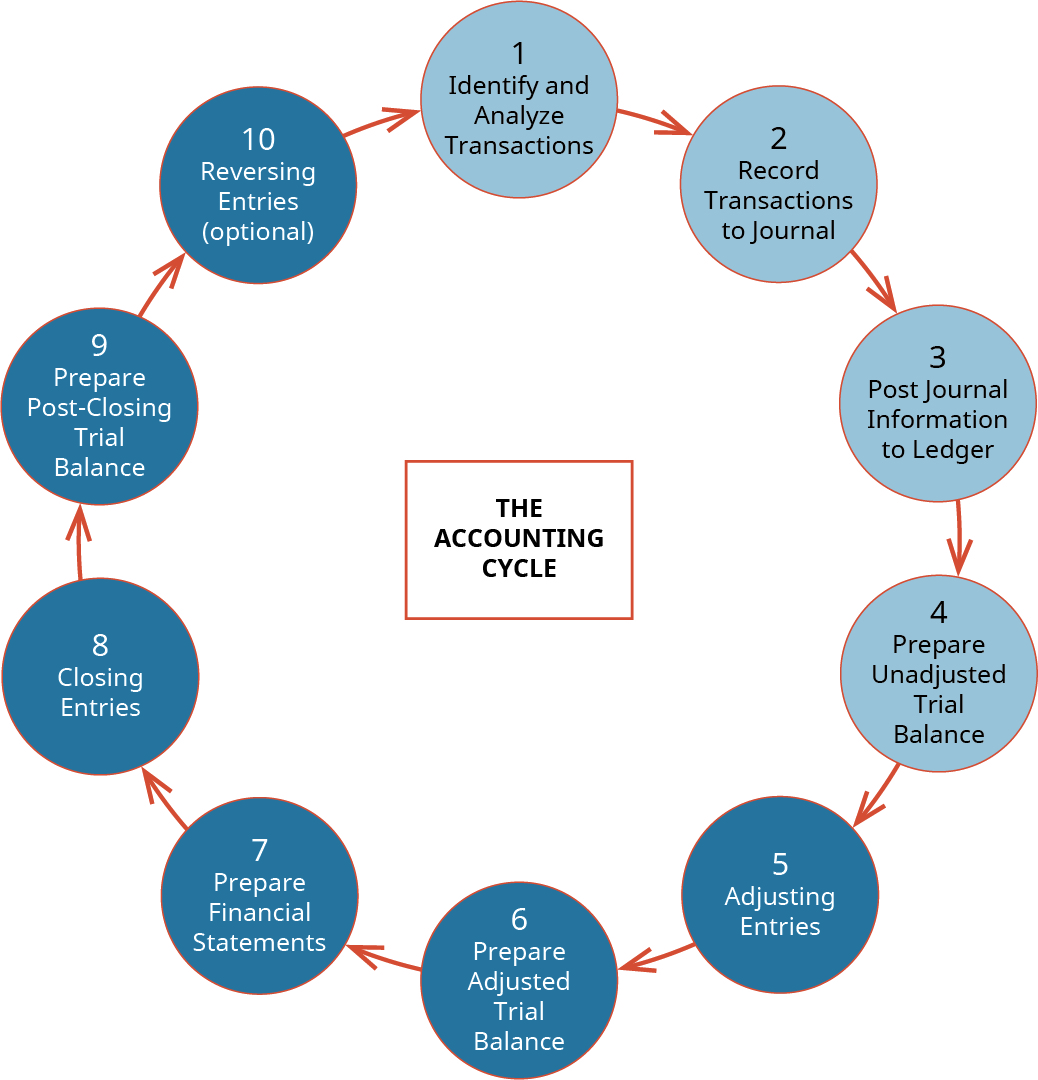

Analyzing and recording transactions represent the first steps in one continuous process known as the accounting cycle. The accounting cycle is a step-by-step process to record business activities and events to keep financial records up to date. The process occurs over one accounting period and will begin the cycle again in the following period. A period is one operating cycle of a business, which could be a month, quarter, or year. Review the accounting cycle in Figure 1.11.

As you can see, the cycle begins with identifying and analyzing transactions, and culminates in reversing entries (which we do not cover in this textbook). The entire cycle is meant to keep financial data organized and easily accessible to both internal and external users of information. In this chapter, we focus on the first four steps in the accounting cycle: identify and analyze transactions, record transactions to a journal, post journal information to a ledger, and prepare an unadjusted trial balance.

In The Adjustment Process we review steps 5, 6, and 7 in the accounting cycle: record adjusting entries, prepare an adjusted trial balance, and prepare financial statements. In Completing the Accounting Cycle, we review steps 8 and 9: closing entries and prepare a post-closing trial balance. As stated previously, we do not cover reversing entries.

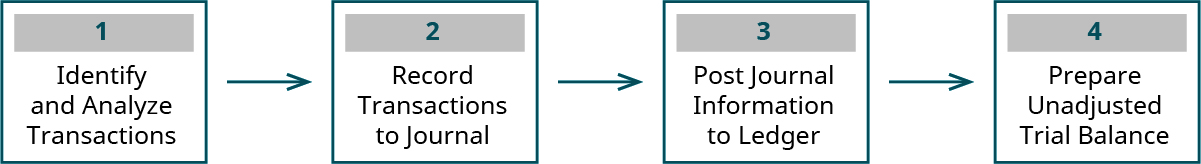

First Four Steps in the Accounting Cycle

The first four steps in the accounting cycle are (1) identify and analyze transactions, (2) record transactions to a journal, (3) post journal information to a ledger, and (4) prepare an unadjusted trial balance. We begin by introducing the steps and their related documentation.

These first four steps set the foundation for the recording process.

Step 1. Identifying and analyzing transactions is the first step in the process. This takes information from original sources or activities and translates that information into usable financial data. An original source is a traceable record of information that contributes to the creation of a business transaction. For example, a sales invoice is considered an original source. Activities would include paying an employee, selling products, providing a service, collecting cash, borrowing money, and issuing stock to company owners. Once the original source has been identified, the company will analyze the information to see how it influences financial records.

Let’s say that Mark Summers of Supreme Cleaners provides cleaning services to a customer. He generates an invoice for $200, the amount the customer owes, so he can be paid for the service. This sales receipt contains information such as how much the customer owes, payment terms, and dates. This sales receipt is an original source containing financial information that creates a business transaction for the company.

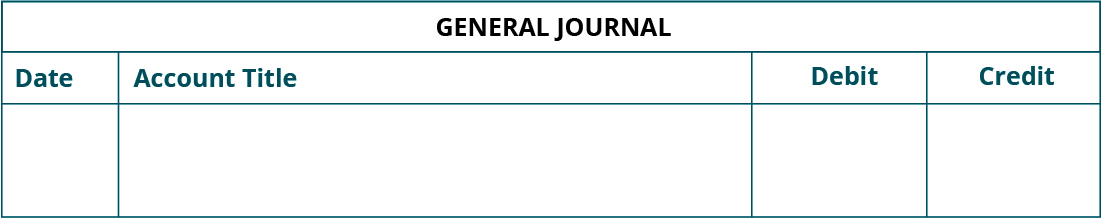

Step 2. The second step in the process is recording transactions to a journal. This takes analyzed data from step 1 and organizes it into a comprehensive record of every company transaction. A transaction is a business activity or event that has an effect on financial information presented on financial statements. The information to record a transaction comes from an original source. A journal (also known as the book of original entry or general journal) is a record of all transactions.

For example, in the previous transaction, Supreme Cleaners had the invoice for $200. Mark Summers needs to record this $200 in his financial records. He needs to choose what accounts represent this transaction, whether or not this transaction will increase or decreases the accounts, and how that impacts the accounting equation before he can record the transaction in his journal. He needs to do this process for every transaction occurring during the period.

Figure 1.13 includes information such as the date of the transaction, the accounts required in the journal entry, and columns for debits and credits.

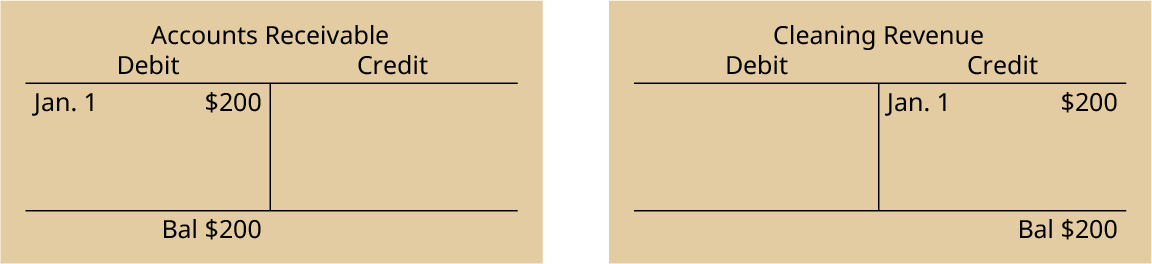

Step 3. The third step in the process is posting journal information to a ledger. Posting takes all transactions from the journal during a period and moves the information to a general ledger, or ledger. As you’ve learned, account balances can be represented visually in the form of T-accounts.

Returning to Supreme Cleaners, Mark identified the accounts needed to represent the $200 sale and recorded them in his journal. He will then take the account information and move it to his general ledger. All of the accounts he used during the period will be shown on the general ledger, not only those accounts impacted by the $200 sale.

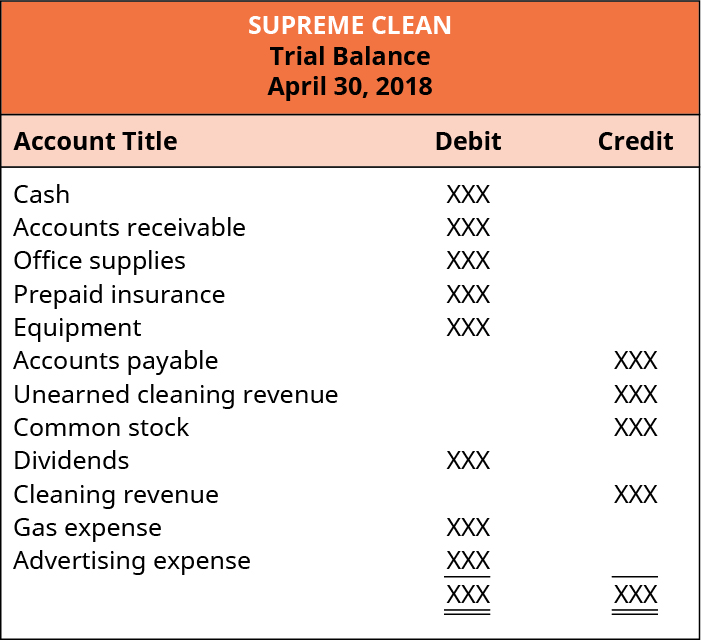

Step 4. The fourth step in the process is to prepare an unadjusted trial balance. This step takes information from the general ledger and transfers it onto a document showing all account balances, and ensuring that debits and credits for the period balance (debit and credit totals are equal).

Mark Summers from Supreme Cleaners needs to organize all of his accounts and their balances, including the $200 sale, onto a trial balance. He also needs to ensure his debits and credits are balanced at the culmination of this step.

It is important to note that recording the entire process requires a strong attention to detail. Any mistakes early on in the process can lead to incorrect reporting information on financial statements. If this occurs, accountants may have to go all the way back to the beginning of the process to find their error. Make sure that as you complete each step, you are careful and really take the time to understand how to record information and why you are recording it. In the next section, you will learn how the accounting equation is used to analyze transactions.

CONCEPTS IN PRACTICE

Forensic Accounting

Ever dream about working for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)? As a forensic accountant, that dream might just be possible. A forensic accountant investigates financial crimes, such as tax evasion, insider trading, and embezzlement, among other things. Forensic accountants review financial records looking for clues to bring about charges against potential criminals. They consider every part of the accounting cycle, including original source documents, looking through journal entries, general ledgers, and financial statements. They may even be asked to testify to their findings in a court of law.

To be a successful forensic accountant, one must be detailed, organized, and naturally inquisitive. This position will need to retrace the steps a suspect may have taken to cover up fraudulent financial activities. Understanding how a company operates can help identify fraudulent activities that veer from the company’s position. Some of the best forensic accountants have put away major criminals such as Al Capone, Bernie Madoff, Ken Lay, and Ivan Boesky.

Long Description

A large circle labeled, in the center, The Accounting Cycle. The large circle consists of 10 smaller circles with arrows pointing from one smaller circle to the next one. Circles 1 through 4 are highlighted. The smaller circles are labeled, in clockwise order: 1 Identify and Analyze Transactions; 2 Record Transactions to Journal; 3 Post Journal Information to Ledger; 4 Prepare Unadjusted Trial Balance; 5 Adjusting Entries; 6 Prepare Adjusted Trial Balance; 7 Prepare Financial Statements; 8 Closing Entries; 9 Prepare Post-Closing Trial Balance; 10 Reversing Entries (optional). Return

Supreme Clean, Trial Balance, April 30, 2018. The balance of each account, whether debit or credit, is listed as XXX. Debit balance accounts are listed as: Cash, Accounts receivable, Office supplies, Prepaid insurance; Equipment, Dividends, Gas expense, and Advertising expense. Credit balance accounts are listed as: Accounts payable, Unearned cleaning revenue, Common stock, and Cleaning revenue. Return

Media Attributions

- General Journal © Rice University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 2 T-accounts © Rice University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- fig2.10SupCln © Rice University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license