3.3 Bad Debt Expense and the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts

You lend a friend $500 with the agreement that you will be repaid in two months. At the end of two months, your friend has not repaid the money. You continue to request the money each month, but the friend has yet to repay the debt. How does this affect your finances?

Think of this on a larger scale. A bank lends money to a couple purchasing a home (mortgage). The understanding is that the couple will make payments each month toward the principal borrowed, plus interest. As time passes, the loan goes unpaid. What happens when a loan that was supposed to be paid is not paid? How does this affect the financial statements for the bank? The bank may need to consider ways to recognize this bad debt.

Fundamentals of Bad Debt Expenses and Allowances for Doubtful Accounts

Bad debts are uncollectible amounts from customer accounts. Bad debt negatively affects accounts receivable (see Figure 3.22). When future collection of receivables cannot be reasonably assumed, recognizing this potential nonpayment is required. There are two methods a company may use to recognize bad debt: the direct write-off method and the allowance method.

The direct write-off method delays recognition of bad debt until the specific customer accounts receivable is identified. Once this account is identified as uncollectible, the company will record a reduction to the customer’s accounts receivable and an increase to bad debt expense for the exact amount uncollectible.

Under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), the direct write-off method is not an acceptable method of recording bad debts, because it violates the matching principle. For example, assume that a credit transaction occurs in September 2018 and is determined to be uncollectible in February 2019. The direct write-off method would record the bad debt expense in 2019, while the matching principle requires that it be associated with a 2018 transaction, which will better reflect the relationship between revenues and the accompanying expenses. This matching issue is the reason accountants will typically use one of the two accrual-based accounting methods introduced to account for bad debt expenses.

It is important to consider other issues in the treatment of bad debts. For example, when companies account for bad debt expenses in their financial statements, they will use an accrual-based method; however, they are required to use the direct write-off method on their income tax returns. This variance in treatment addresses taxpayers’ potential to manipulate when a bad debt is recognized. Because of this potential manipulation, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires that the direct write-off method must be used when the debt is determined to be uncollectible, while GAAP still requires that an accrual-based method be used for financial accounting statements.

For the taxpayer, this means that if a company sells an item on credit in October 2018 and determines that it is uncollectible in June 2019, it must show the effects of the bad debt when it files its 2019 tax return. This application probably violates the matching principle, but if the IRS did not have this policy, there would typically be a significant amount of manipulation on company tax returns. For example, if the company wanted the deduction for the write-off in 2018, it might claim that it was actually uncollectible in 2018, instead of in 2019.

The final point relates to companies with very little exposure to the possibility of bad debts, typically, entities that rarely offer credit to its customers. Assuming that credit is not a significant component of its sales, these sellers can also use the direct write-off method. The companies that qualify for this exemption, however, are typically small and not major participants in the credit market. Thus, virtually all of the remaining bad debt expense material discussed here will be based on an allowance method that uses accrual accounting, the matching principle, and the revenue recognition rules under GAAP.

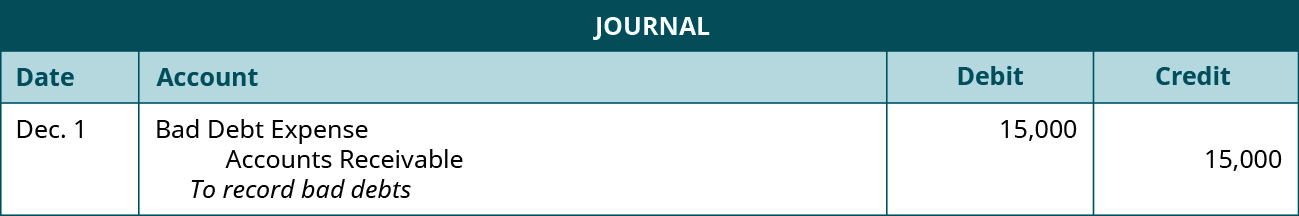

For example, a customer takes out a $15,000 car loan on August 1, 2018 and is expected to pay the amount in full before December 1, 2018. For the sake of this example, assume that there was no interest charged to the buyer because of the short-term nature or life of the loan. When the account defaults for nonpayment on December 1, the company would record the following journal entry to recognize bad debt.

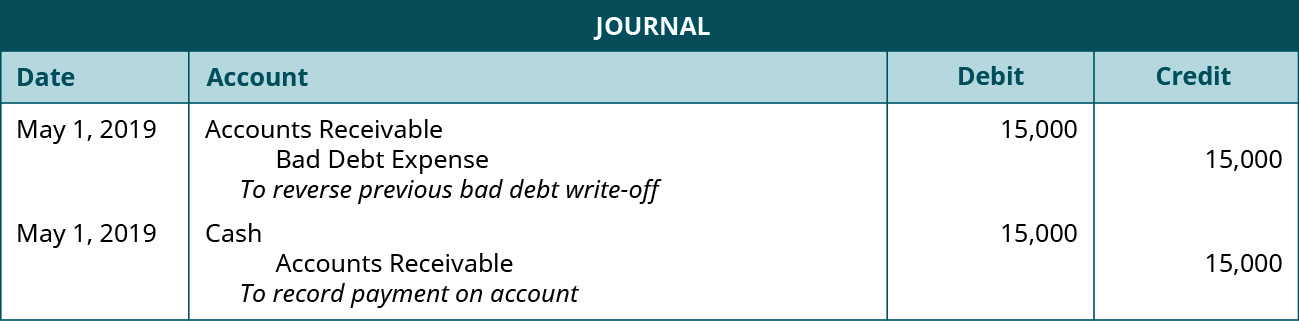

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit), and Accounts Receivable decreases (credit) for $15,000. If, in the future, any part of the debt is recovered, a reversal of the previously written-off bad debt, and the collection recognition is required. Let’s say this customer unexpectedly pays in full on May 1, 2019, the company would record the following journal entries (note that the company’s fiscal year ends on June 30)

The first entry reverses the bad debt write-off by increasing Accounts Receivable (debit) and decreasing Bad Debt Expense (credit) for the amount recovered. The second entry records the payment in full with Cash increasing (debit) and Accounts Receivable decreasing (credit) for the amount received of $15,000.

As you’ve learned, the delayed recognition of bad debt violates GAAP, specifically the matching principle. Therefore, the direct write-off method is not used for publicly traded company reporting; the allowance method is used instead.

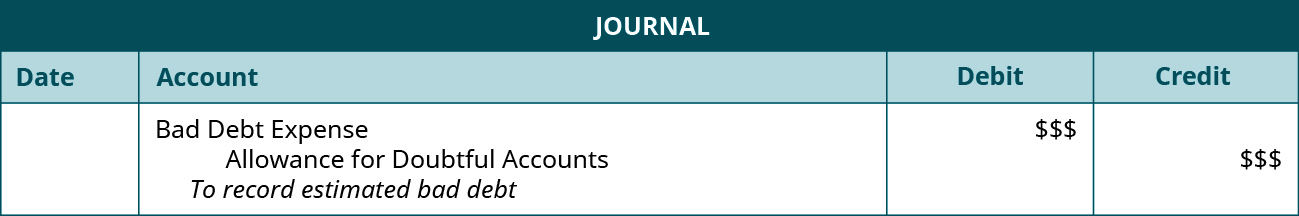

The allowance method is the more widely used method because it satisfies the matching principle. The allowance method estimates bad debt during a period, based on certain computational approaches. The calculation matches bad debt with related sales during the period. The estimation is made from past experience and industry standards. When the estimation is recorded at the end of a period, the following entry occurs.

The journal entry for the Bad Debt Expense increases (debit) the expense’s balance, and the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts increases (credit) the balance in the Allowance. The allowance for doubtful accounts is a contra asset account and is subtracted from Accounts Receivable to determine the Net Realizable Value of the Accounts Receivable account on the balance sheet. A contra account has an opposite normal balance to its paired account, thereby reducing or increasing the balance in the paired account at the end of a period; the adjustment can be an addition or a subtraction from a controlling account. In the case of the allowance for doubtful accounts, it is a contra account that is used to reduce the Controlling account, Accounts Receivable.

At the end of an accounting period, the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts reduces the Accounts Receivable to produce Net Accounts Receivable. Note that allowance for doubtful accounts reduces the overall accounts receivable account, not a specific accounts receivable assigned to a customer. Because it is an estimation, it means the exact account that is (or will become) uncollectible is not yet known.

To demonstrate the treatment of the allowance for doubtful accounts on the balance sheet, assume that a company has reported an Accounts Receivable balance of $90,000 and a Balance in the Allowance of Doubtful Accounts of $4,800. The following table reflects how the relationship would be reflected in the current (short-term) section of the company’s Balance Sheet.

There is one more point about the use of the contra account, Allowance for Doubtful Accounts. In this example, the $85,200 total is the net realizable value, or the amount of accounts anticipated to be collected. However, the company is owed $90,000 and will still try to collect the entire $90,000 and not just the $85,200.

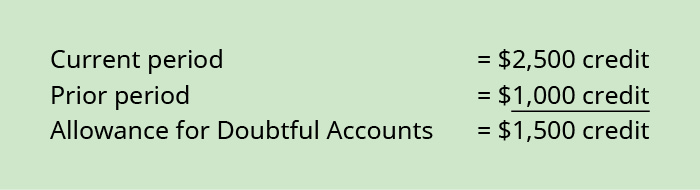

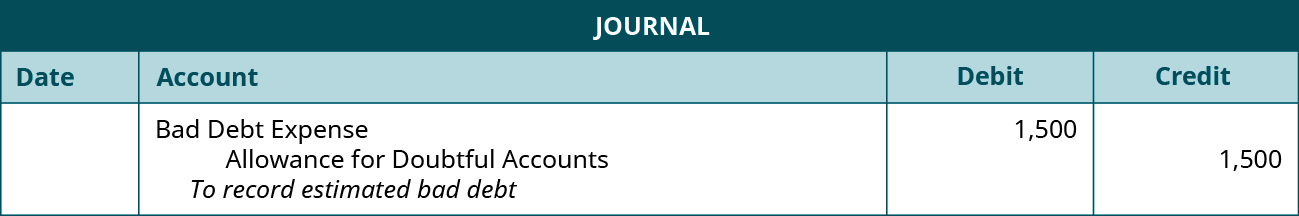

Under the balance sheet method of calculating bad debt expenses, if there is already a balance in Allowance for Doubtful Accounts from a previous period and accounts written off in the current year, this must be considered before the adjusting entry is made. For example, if a company already had a credit balance from the prior period of $1,000, plus any accounts that have been written off this year, and a current period estimated balance of $2,500, the company would need to subtract the prior period’s credit balance from the current period’s estimated credit balance in order to calculate the amount to be added to the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts.

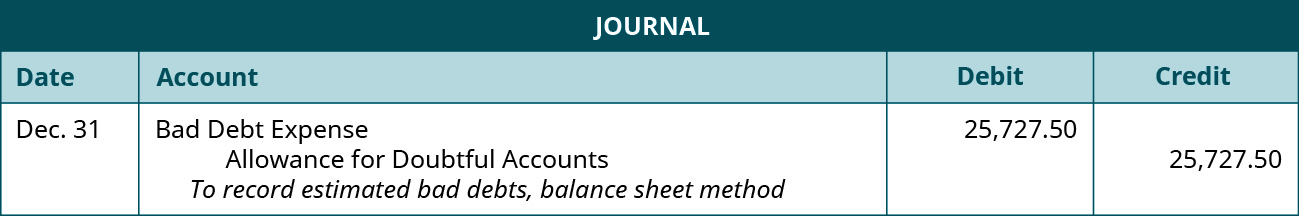

Therefore, the adjusting journal entry would be as follows.

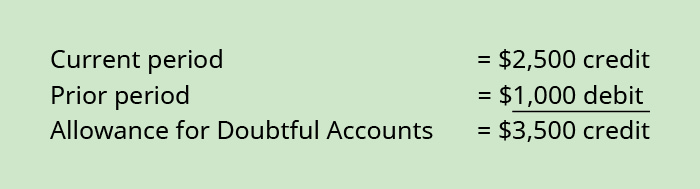

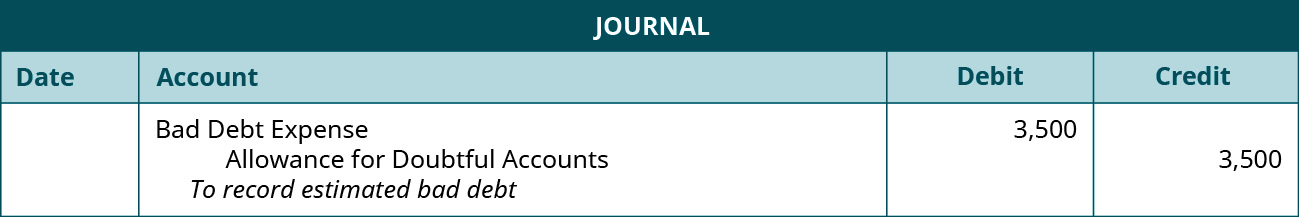

If a company already had a debit balance from the prior period of $1,000, and a current period estimated balance of $2,500, the company would need to add the prior period’s debit balance to the current period’s estimated credit balance.

Therefore, the adjusting journal entry would be as follows.

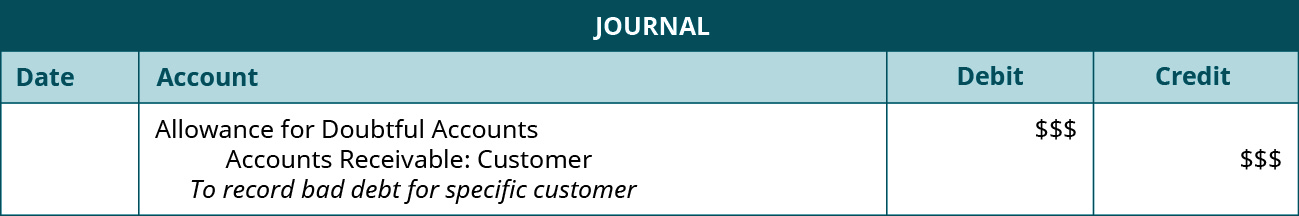

When a specific customer has been identified as an uncollectible account, the following journal entry would occur.

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts decreases (debit) and Accounts Receivable for the specific customer also decreases (credit). Allowance for doubtful accounts decreases because the bad debt amount is no longer unclear. Accounts receivable decreases because there is an assumption that no debt will be collected on the identified customer’s account.

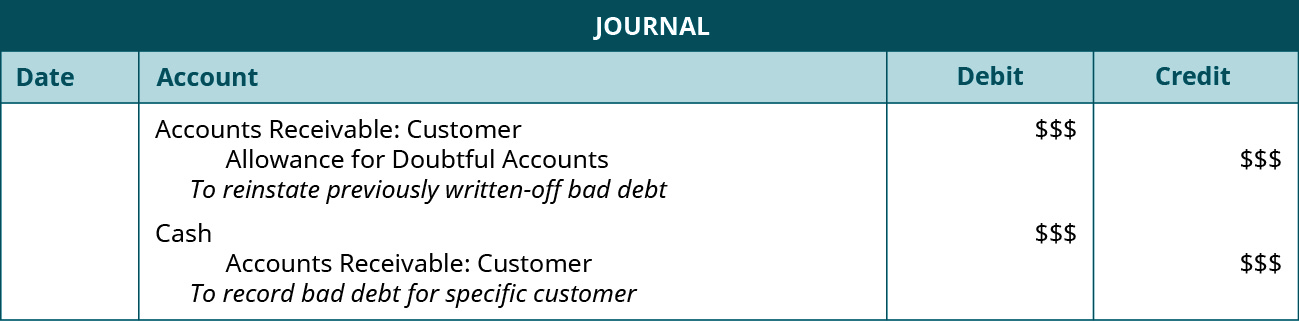

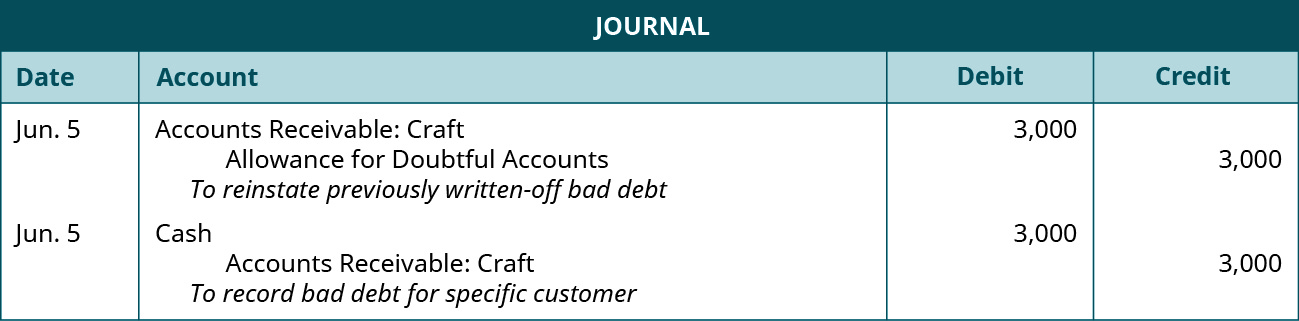

Let’s say that the customer unexpectedly pays on the account in the future. The following journal entries would occur.

The first entry reverses the previous entry where bad debt was written off. This reinstatement requires Accounts Receivable: Customer to increase (debit), and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts to increase (credit). The second entry records the payment on the account. Cash increases (debit) and Accounts Receivable: Customer decreases (credit) for the amount received.

To compute the most accurate estimation possible, a company may use one of three methods for bad debt expense recognition: the income statement method, balance sheet method, or balance sheet aging of receivables method.

The income statement method (also known as the percentage of sales method) estimates bad debt expenses based on the assumption that at the end of the period, a certain percentage of sales during the period will not be collected. The estimation is typically based on credit sales only, not total sales (which include cash sales). In this example, assume that any credit card sales that are uncollectible are the responsibility of the credit card company. It may be obvious intuitively, but, by definition, a cash sale cannot become a bad debt, assuming that the cash payment did not entail counterfeit currency. The income statement method is a simple method for calculating bad debt, but it may be more imprecise than other measures because it does not consider how long a debt has been outstanding and the role that plays in debt recovery.

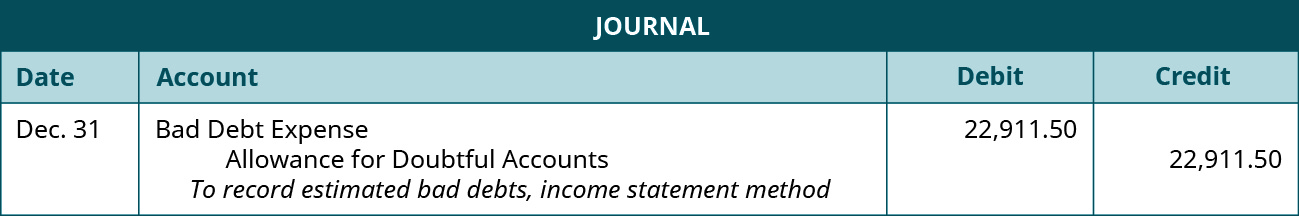

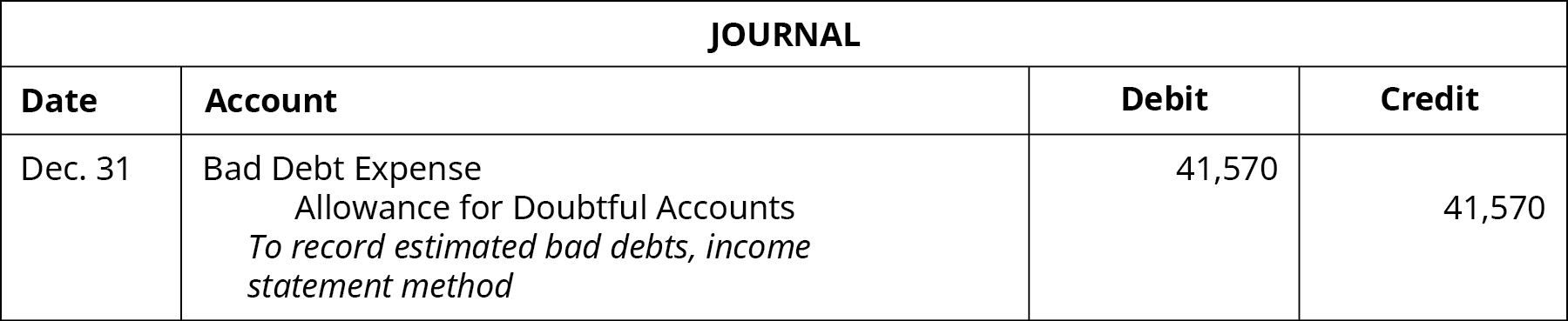

To illustrate, let’s continue to use Billie’s Watercraft Warehouse (BWW) as the example. Billie’s end-of-year credit sales totaled $458,230. BWW estimates that 5% of its overall credit sales will result in bad debt. The following adjusting journal entry for bad debt occurs.

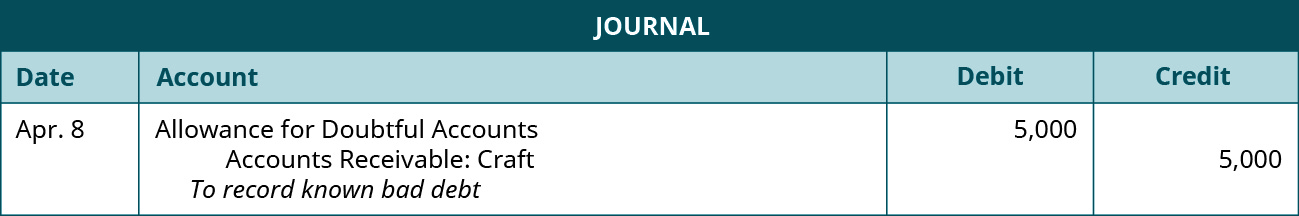

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit), and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts increases (credit) for $22,911.50 ($458,230 × 5%). This means that BWW believes $22,911.50 will be uncollectible debt. Let’s say that on April 8, it was determined that Customer Robert Craft’s account was uncollectible in the amount of $5,000. The following entry occurs.

In this case, Allowance for Doubtful Accounts decreases (debit) and Accounts Receivable: Craft decreases (credit) for the known uncollectible amount of $5,000. On June 5, Craft unexpectedly makes a partial payment on his account in the amount of $3,000. The following journal entries show the reinstatement of bad debt and the subsequent payment.

The outstanding balance of $2,000 that Craft did not repay will remain as bad debt.

Income Statement Approach: Percentage of Sales

YOUR TURN

Heating and Air Company

You run a successful heating and air conditioning company. Your net credit sales, accounts receivable, and allowance for doubtful accounts figures for year-end 2018, follow.

- Compute bad debt estimation using the income statement method, where the percentage uncollectible is 5%.

- Prepare the journal entry for the income statement method of bad debt estimation.

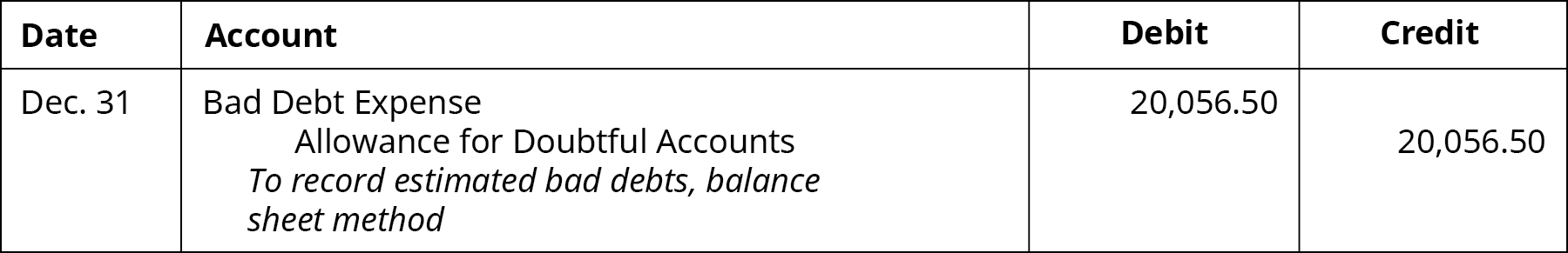

- Compute bad debt estimation using the balance sheet method of percentage of receivables, where the percentage uncollectible is 9%.

- Prepare the journal entry for the balance sheet method bad debt estimation.

Solution

- $41,570; $831,400 × 5%

Figure 3.37 By: Rice University Source: Openstax CC BY-NC-SA - $20,056.50; $222,850 × 9%

Figure 3.38 By: Rice University Source: Openstax CC BY-NC-SA

Balance Sheet Method for Calculating Bad Debt Expenses

The balance sheet method (also known as the percentage of accounts receivable method) estimates bad debt expenses based on the balance in accounts receivable. The method looks at the balance of accounts receivable at the end of the period and assumes that a certain amount will not be collected. Accounts receivable is reported on the balance sheet; thus, it is called the balance sheet method. The balance sheet method is another simple method for calculating bad debt, but it too does not consider how long a debt has been outstanding and the role that plays in debt recovery. There is a variation on the balance sheet method, however, called the aging method that does consider how long accounts receivable have been owed, and it assigns a greater potential for default to those debts that have been owed for the longest period of time.

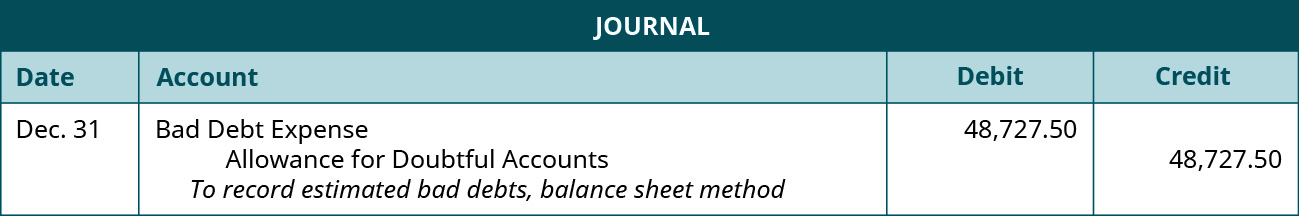

Continuing our examination of the balance sheet method, assume that BWW’s end-of-year accounts receivable balance totaled $324,850. This entry assumes a zero balance in Allowance for Doubtful Accounts from the prior period. BWW estimates 15% of its overall accounts receivable will result in bad debt. The following adjusting journal entry for bad debt occurs.

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit), and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts increases (credit) for $48,727.50 ($324,850 × 15%). This means that BWW believes $48,727.50 will be uncollectible debt. Let’s consider that BWW had a $23,000 credit balance from the previous period. The adjusting journal entry would recognize the following.

This is different from the last journal entry, where bad debt was estimated at $48,727.50. That journal entry assumed a zero balance in Allowance for Doubtful Accounts from the prior period. This journal entry takes into account a credit balance of $23,000 and subtracts the prior period’s balance from the estimated balance in the current period of $48,727.50.

Balance Sheet Aging of Receivables Method for Calculating Bad Debt Expenses

The balance sheet aging of receivables method estimates bad debt expenses based on the balance in accounts receivable, but it also considers the uncollectible time period for each account. The longer the time passes with a receivable unpaid, the lower the probability that it will get collected. An account that is 90 days overdue is more likely to be unpaid than an account that is 30 days past due.

With this method, accounts receivable is organized into categories by length of time outstanding, and an uncollectible percentage is assigned to each category. The length of uncollectible time increases the percentage assigned. For example, a category might consist of accounts receivable that is 0–30 days past due and is assigned an uncollectible percentage of 6%. Another category might be 31–60 days past due and is assigned an uncollectible percentage of 15%. All categories of estimated uncollectible amounts are summed to get a total estimated uncollectible balance. That total is reported in Bad Debt Expense and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts, if there is no carryover balance from a prior period. If there is a carryover balance, that must be considered before recording Bad Debt Expense. The balance sheet aging of receivables method is more complicated than the other two methods, but it tends to produce more accurate results. This is because it considers the amount of time that accounts receivable has been owed, and it assumes that the longer the time owed, the greater the possibility that individual accounts receivable will prove to be uncollectible.

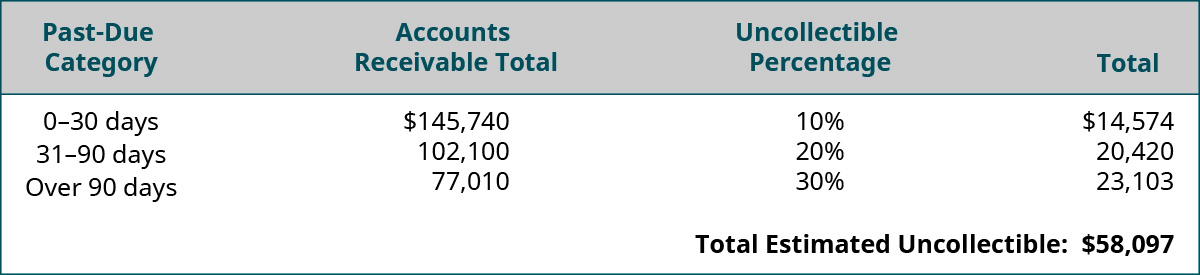

Looking at BWW, it has an accounts receivable balance of $324,850 at the end of the year. The company splits its past-due accounts into three categories: 0–30 days past due, 31–90 days past due, and over 90 days past due. The uncollectible percentages and the accounts receivable breakdown are shown here.

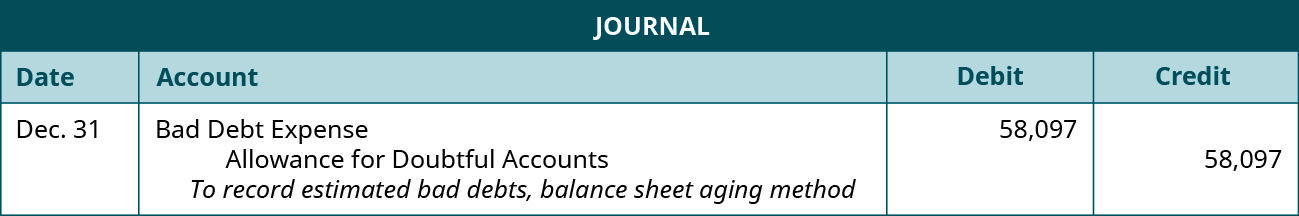

For each of the individual categories, the accountant multiplies the uncollectible percentage by the accounts receivable total for that category to get the total balance of estimated accounts that will prove to be uncollectible for that category. Then all of the category estimates are added together to get one total estimated uncollectible balance for the period. The entry for bad debt would be as follows, if there was no carryover balance from the prior period.

Bad Debt Expense increases (debit) as does Allowance for Doubtful Accounts (credit) for $58,097. BWW believes that $58,097 will be uncollectible debt.

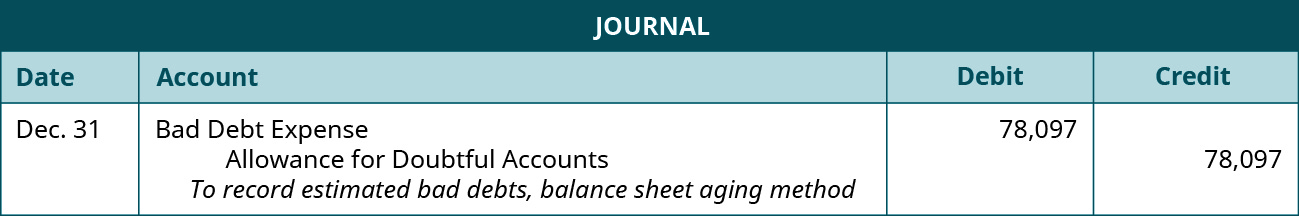

Let’s consider a situation where BWW had a $20,000 debit balance from the previous period. The adjusting journal entry would recognize the following.

This is different from the last journal entry, where bad debt was estimated at $58,097. That journal entry assumed a zero balance in Allowance for Doubtful Accounts from the prior period. This journal entry takes into account a debit balance of $20,000 and adds the prior period’s balance to the estimated balance of $58,097 in the current period.

You may notice that all three methods use the same accounts for the adjusting entry; only the method changes the financial outcome. Also note that it is a requirement that the estimation method be disclosed in the notes of financial statements so stakeholders can make informed decisions.

CONCEPTS IN PRACTICE

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

As of January 1, 2018, GAAP requires a change in how health-care entities record bad debt expense. Before this change, these entities would record revenues for billed services, even if they did not expect to collect any payment from the patient. This uncollectible amount would then be reported in Bad Debt Expense. Under the new guidance, the bad debt amount may only be recorded if there is an unexpected circumstance that prevented the patient from paying the bill, and it may only be calculated from the amount that the providing entity anticipated collecting.

For example, a patient receives medical services at a local hospital that cost $1,000. The hospital knows in advance that the patient will pay only $100 of the amount owed. The previous GAAP rules would allow the company to write off $900 to bad debt. Under the current rule, the company may only consider revenue to be the expected amount of $100. For example, if the patient ran into an unexpected job loss and is able to pay only $20 of the $100 expected, the hospital would record the $20 to revenue and the $80 ($100 − $20) as a write-off to bad debt. This is a significant change in revenue reporting and bad debt expense. Health-care entities will more than likely see a decrease in bad debt expense and revenues as a result of this change.1

Footnotes

- 1 Tara Bannow. “New Bad Debt Accounting Standards Likely to Remake Community Benefit Reporting.” Modern Healthcare. March 17, 2018. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180317/NEWS/180319904