Chapter 2: Classical Theories of Emotion

Schachter-Singer Two-Factor Theory

Stanley Schachter was born in Queens, New York. He attended Yale University for art history, eventually switching to psychology. After his undergraduate years, he received a Master’s in Psychology from Yale University and worked closely with Clark Hull (a learning theorist; drive reduction theory). After working for a bit, he attended MIT for a doctoral degree under Kurt Lewin (a Gestalt psychologist and early founder of social psychology). His student peers included other famous social psychologists like Leon Festinger (cognitive dissonance theory), Harold Kelley (covariation model; interdependence theory), and John Thibaut (interdependence theory). When Lewin suddenly died, Festinger took over Lewin’s lab and became Schachter’s doctoral adviser. Eventually, Festinger moved the doctoral program to the University of Michigan, where Schachter was awarded his doctorate in psychology. Schachter held positions at the University of Minnesota and later returned to his roots at Columbia University.

Jerome Singer was born in the Bronx, New York. Singer attended a doctoral program in psychology at the University of Minnesota under his adviser – Stanley Schachter! He held professorships at Penn State University (woo hoo!) and the State University of New York’s Stony Brook. It is important to note that Schachter and Singer were trained as social psychologists, whereas Cannon and Bard were trained as medical doctors and physiologists. Their early academic programs clearly influenced their views of emotion.

Schachter and Singer’s (1962) Two-Factor Theory of Emotion suggests that physiological arousal determines the strength of the emotion, while cognitive appraisal identifies the emotion label. So, in this theory, the “two-factor” represents physiological change and cognitive appraisal change.

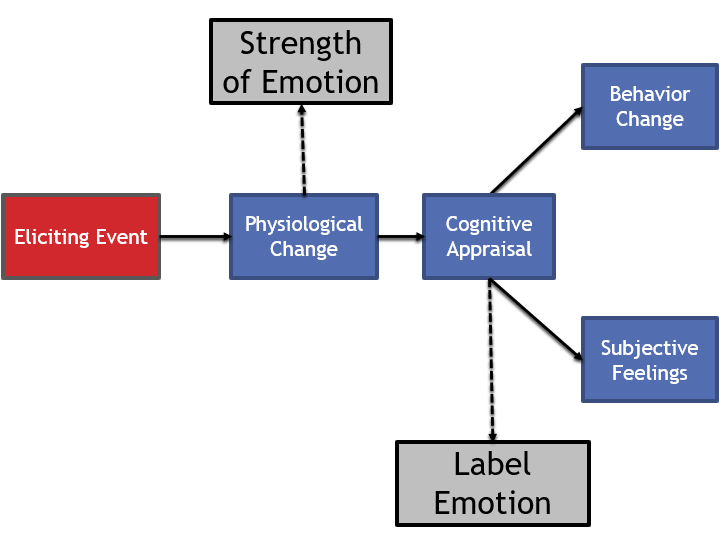

Figure 5

Model of Schachter-Singer’s Two-Factor Theory of Emotion

Long Description

The image is a flowchart illustrating the process of emotional response. It begins with a red rectangle labeled “Eliciting Event,” which points to a blue rectangle labeled “Physiological Change” via a black arrow. The “Physiological Change” box is connected by a solid black arrow to another blue rectangle labeled “Cognitive Appraisal.” Above these, a gray rectangle labeled “Strength of Emotion” is linked by a dashed arrow to the “Physiological Change” box. The “Cognitive Appraisal” box extends a solid black arrow to two blue rectangles labeled “Behavior Change” and “Subjective Feelings.” Below these, a gray rectangle labeled “Label Emotion” is connected via a dashed arrow from the “Cognitive Appraisal” box. The layout shows a series of causative and evaluative processes represented by arrows and colored boxes.

Figure 5 above shows their theory. The eliciting event causes a change in physiology and a change in cognitive appraisal. According to this theory, physical arousal occurs first and instigates the cognitive appraisal process. Physiological changes tell us how intensely we are experiencing the emotion. High levels of physiological arousal would represent a strong or intense emotion, whereas low levels of physiological arousal represent a weak or less intense level of arousal. According to Schachter and Singer, we cannot determine the emotion label from our arousal level. This is because most emotions evoke similar physiological responses (heart beating, sweating, pupil dilation). Our cognitive appraisal of the event and of our physiological changes determine the label we attach to our emotional experience. This cognitive appraisal could be quick and automatic or slow and conscious. Our cognitive appraisal determines our behavior changes and subjective feelings. In other words, we don’t know how to behave or how to consciously label our emotion until we appraise the situation!

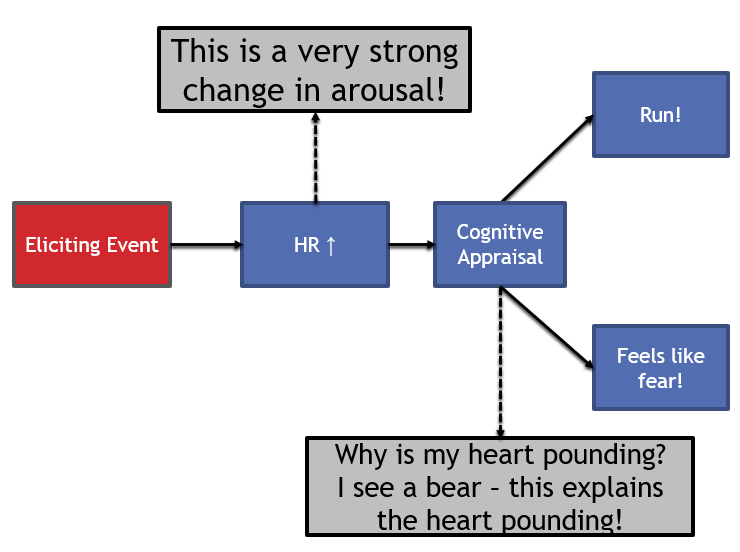

Long Description

The image depicts a flowchart illustrating a psychological response process. It begins with a red rectangle labeled “Eliciting Event” on the left, which points to a blue rectangle labeled “HR ↑” in the center, indicating an increase in heart rate. Above this, a gray box with dashed lines reads, “This is a very strong change in arousal!” The “HR ↑” box points to another blue rectangle labeled “Cognitive Appraisal.” From here, two arrows extend: one leading to a blue rectangle with “Run!” and another leading to another blue rectangle with “Feels like fear!” Below the “Cognitive Appraisal” box, a gray box connected with dashed lines reads, “Why is my heart pounding? I see a bear – this explains the heart pounding!”

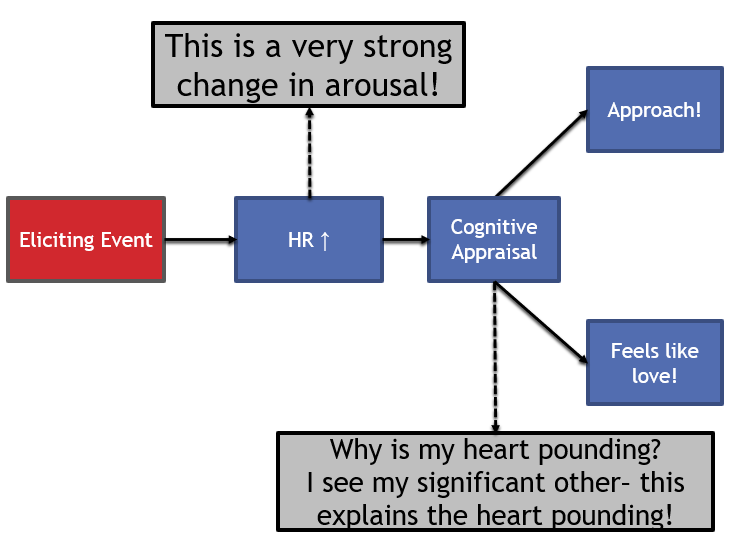

Long Description

The image is a flowchart illustrating a psychological process involving an eliciting event leading to cognitive appraisal. It begins with a red rectangle labeled “Eliciting Event” on the left. An arrow points from this box to a blue rectangle labeled “HR ↑,” indicating an increase in heart rate. From here, two arrows emerge. One arrow leads upwards to a gray rectangle labeled “This is a very strong change in arousal!” The second arrow leads to another blue rectangle labeled “Cognitive Appraisal.” From “Cognitive Appraisal,” two additional arrows branch out to blue rectangles labeled “Approach!” and “Feels like love!” respectively. Below these, another arrow leads to a gray rectangle with the text “Why is my heart pounding? I see my significant other—this explains the heart pounding!”