Chapter 9: Anger

Behavior Changes

In this section, we will discuss evidence for both the basic emotion and social constructivist perspective of anger.

Facial Expressions of Anger: Basic or Social Constructivist?

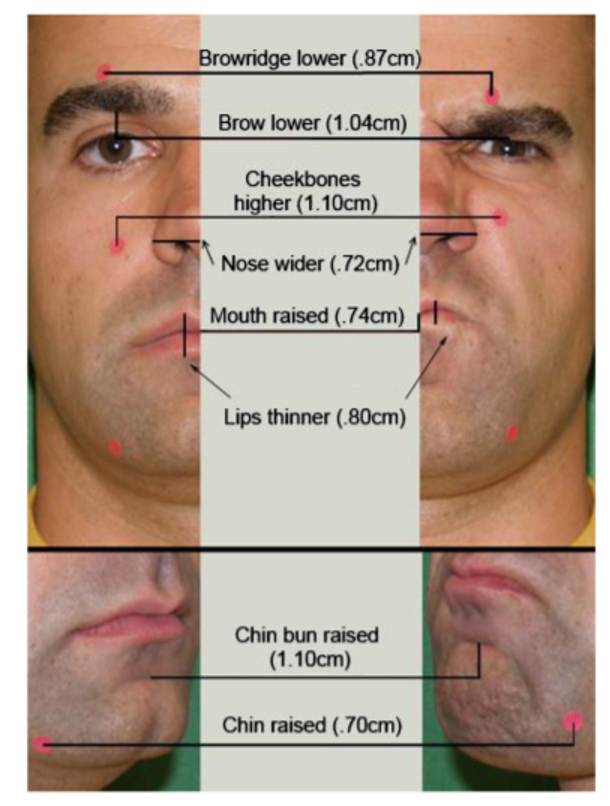

Facial expressions change during an anger experience. In the FACS (Ekman & Friesen, 1978, displayed in Figure 2), the following action units were associated with anger:

- AU 4: Brow lowerer

- AU 5: Upper lid raiser (“the glare”)

- AU 7: Lid-tightener (“the squint”)

- AU 10: Upper lip raiser

- AU 17: Chin raiser

- AU 22: Lip funneler

- AU 23: Lip tightener

- AU 24: Lip pressor

Figure 2

AUs for Anger

Note. Face on right represents anger expression; face on left represents opposite of each anger action unit. Reproduced from A. Sell, L. Cosmides, and J. Tooby, 2014, Evolution and Human Behavior 35(5), p. 426 (The human anger face evolved to enhance cues of strength). Copyright 2014 by Elsevier.

Visit this website for a live demonstration of how the AUs for anger change. Some believe this anger expression is a universal, adaptive signal. During eliciting events of anger, the anger facial expression functioned to display an individual’s strength and probability of winning a fight. In fact, research shows people perceive composite faces showing only one anger action unit change to be physically stronger than the same face showing opposite facial action changes (Sell et al., 2014). Across several industrialized and isolated cultures, Ekman has found people universally recognize the anger facial expression. Similar to findings on fear (Ekman et al., 1969, for a review click here), the majority of participants correctly identified anger, but the Fore and Borneo participants showed lower recognition rates than other countries (see Table 1). In the USA and Japan, some participants incorrectly labeled the anger expression disgust, while the Fore tribe mistakenly labeled anger fear. This is interesting because the Fore tribe also mislabeled fear as anger. So, there appears to be some overlap in anger and fear for the Fore tribe.

Table 1

Recognition Rates for Six Emotions Across Five Cultures

| Affect Category | United States | Brazil | Japan | New Guinea Pidgin Responses | New Guinea Fore Responses | Borneo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happy (H) | 97 H | 97 H | 87 H | 99 H | 82 H | 92 H |

| Fear (F) | 88 F | 77 F | 71 F

26 Su |

46 F

31 A |

54 F

25 A |

40 F

33 Su |

| Disgust-contempt (D) | 82 D | 86 D | 82 D | 29 D

23 A |

44 D

30 A |

26 Sa

23 H |

| Anger (A) | 69 A

29 D |

82 A | 63 A

14 D |

56 A

22 F |

50 A

25 F |

64 A |

| Surprise (Su) | 91 Su | 82 Su | 87 Su | 38 Su

30 F |

45 F

19 A |

36 Su

23 F |

| Sadness (Sa) | 73 Sa | 82 Sa | 74 Sa | 55 Sa

23 A |

56 A | 52 Sa |

Reproduced from “Pan-cultural Elements in Facial Displays of Emotion,” by P. Ekman, E.R. Sorenson, and W.V. Friesen, 1969, Science, 164(3875), p. 87, (Pan-Cultural Elements in Facial Displays of Emotion). Copyright Note. For the Fore tribe, some words were in Pidgin language, others in Fore language.

Table 2

Results for Adult Participants (Ekman & Friesen, 1971)

Anger Story

| Emotion Shown in the three photographs | Numbers | % Choosing correct face |

|---|---|---|

| Anger, Sadness, surprise | 66 | 82% |

| Anger, Disgust, surprise | 31 | 87% |

| Anger, Fear, sadness | 31 | 87% |

Reproduced from “Constants across Cultures in the Face and Emotion,” by P. Ekman, E.R. and W.V. Friesen, 1971, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(2), p. 127, (Constants across cultures in the face and emotion.). Copyright 2016 by the American Psychological Association

Table 3

Results for Child Participants (Ekman & Friesen, 1971)

Anger Story

| Emotion Shown in the two photographs | Numbers | % Choosing correct face |

|---|---|---|

| Anger, Sadness | 69 | 90% |

Reproduced from “Constants across Cultures in the Face and Emotion,” by P. Ekman, E.R. and W.V. Friesen, 1971, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(2), p. 127, (Constants across cultures in the face and emotion.). Copyright 2016 by the American Psychological Association

Finally, Ekman and colleagues (1987, for review of study click here) found that across 10 cultures, the majority of participants identified anger in facial expressions and rated anger facial expressions as most intensely anger out of 7 possible emotions.

Let’s review some other studies we discussed in the fear section. You might recall that is Matsumoto’s (1992) study, participants saw 48 photos of six emotional expressions (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise). Each emotion was displayed in 8 different photos. Participants viewed all 48 photos one at a time. While viewing each photo, participants picked an emotion label from the following seven emotions: anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. Results for anger showed that 89.58% of American participants and 64.20% of Japanese participants correctly labeled the anger expression as anger across the 8 fear photos. This parallels findings for fear, in which about 82% of Americans and 54% of Japanese answered correctly. Similar to findings on fear, two cultural differences were found: 1) a significantly greater number of Americans identified anger in the angry facial expressions and 2) on average, Americans identified 7.17 out of the 8 photos as anger, whereas Japanese identified fewer – about 5.14 photos. A similar study by Matsumoto and Ekman (1989) found that 87.12% of Americans and 69.64% of Japanese correctly identified anger across eight photos, demonstrating universality in facial expression identification.

Recall that Crivelli, Russell, and colleagues (2016) asked Spaniards and Trobrianders (Study 1) and Mwani children (Study 2) to pick the correct photo or video of an emotional expression that showed one of five different emotions. In Study 1 in the anger condition, a significantly greater percentage of Spaniards (91%) than Trobrianders (7%) correctly selected the photo of the angry scowl facial expression. Most of the Trobrianders picked the fear gasp (30%) as the photo that represented anger, followed by the disgust nose scrunch (20%), the happy smiling face (20%), and the sad pouting face (17%). Only 9% of the Spaniards incorrectly picked the disgust nose scrunch. These findings show that the angry scowl most Western cultures perceive to display anger does not hold in other cultures. In Study 2, only 18-26% of Mwani children selected the angry scowl in the video or photo as representative of anger. Mwani children also selected the fear gasp, disgust nose scrunch, and pouting face as showing anger.

In Barrett’s study (Gendron et al., 2014b), the American participants free sorted scowl faces into the same piles, while the Himba did not. Instead, sometimes the Himba grouped scowls into piles with nose scrunches, neutral faces, OR even pouting faces! Thus, although this study found universality for fear and joy, these findings did not present for the emotion anger.