Chapter 10: Disgust

Animal-Nature Disgust

Animal-nature disgust is the second type of disgust. When the eliciting event reminds us that we ourselves are animals, animal-nature disgust is elicited. Animal-nature disgust occurs when the boundaries between humans and animals are blurred, thus reminding us that we are just as vulnerable to death as other animals. This type of disgust may have developed after core disgust. Instead of focusing on the mouth like core disgust, animal-nature disgust expands the disgust emotion to the entire body.Haidt et al. (1997) asked participants to list the most disgusting things they could think of, then categorized their answers into groups based on similarity. They found that 25% of the items represented core disgust, whereas 75% of the items did not relate to the mouth, food, or bodily products. The remaining 75% of these events could be grouped into the following types of eliciting events:

| Type of Animal-Nature Disgust | Definitions and/or Examples |

|---|---|

| Inappropriate sexual acts (e.g.,) | bestiality, incest, child sexual abuse, large age differences in sexual partners |

| Poor hygiene | scabies, lice, skin diseases, foul odors |

| Death (e.g.,) | corpses, graveyards, smell of decay |

| Envelope Violations | when the external body is breached or altered; (e.g., gore, deformity, obesity, blood, surgery, open wounds) |

These four groups represent the eliciting events that cause animal-nature disgust. In fact, these four events are additional ways in which we could contract diseases or infections and thus animal-nature disgust may have evolved as an adaptation to maintain our health. When we hear about these four events occurring, or experience them ourselves, we are reminded of our animal nature and experience animal-nature disgust. Specifically, envelope violations, remind us that we are vulnerable animals whose bodies could be harmed at any time. Terror Management Theory (TMT; Greenberg et al., 1986) suggests that thinking about our own death is threatening and causes death anxiety or “terror.” In turn, this death anxiety lowers our self-esteem. TMT further states that when we experience this death-related anxiety we in turn engage in behaviors or thoughts to reduce the anxiety and to maintain our self-esteem. For example, when thoughts of death are accessible, people adhere more to their cultural worldviews (e.g., religion, culture, personal morals; Greenberg et al., 1990), draw closer to their relationship partners (Florian et al., 2002; Mikulincer et al. 2004), and engage in healthy behaviors (e.g., smoke less, exercise more; Arndt et al., 2003; Bozo et al., 2009).

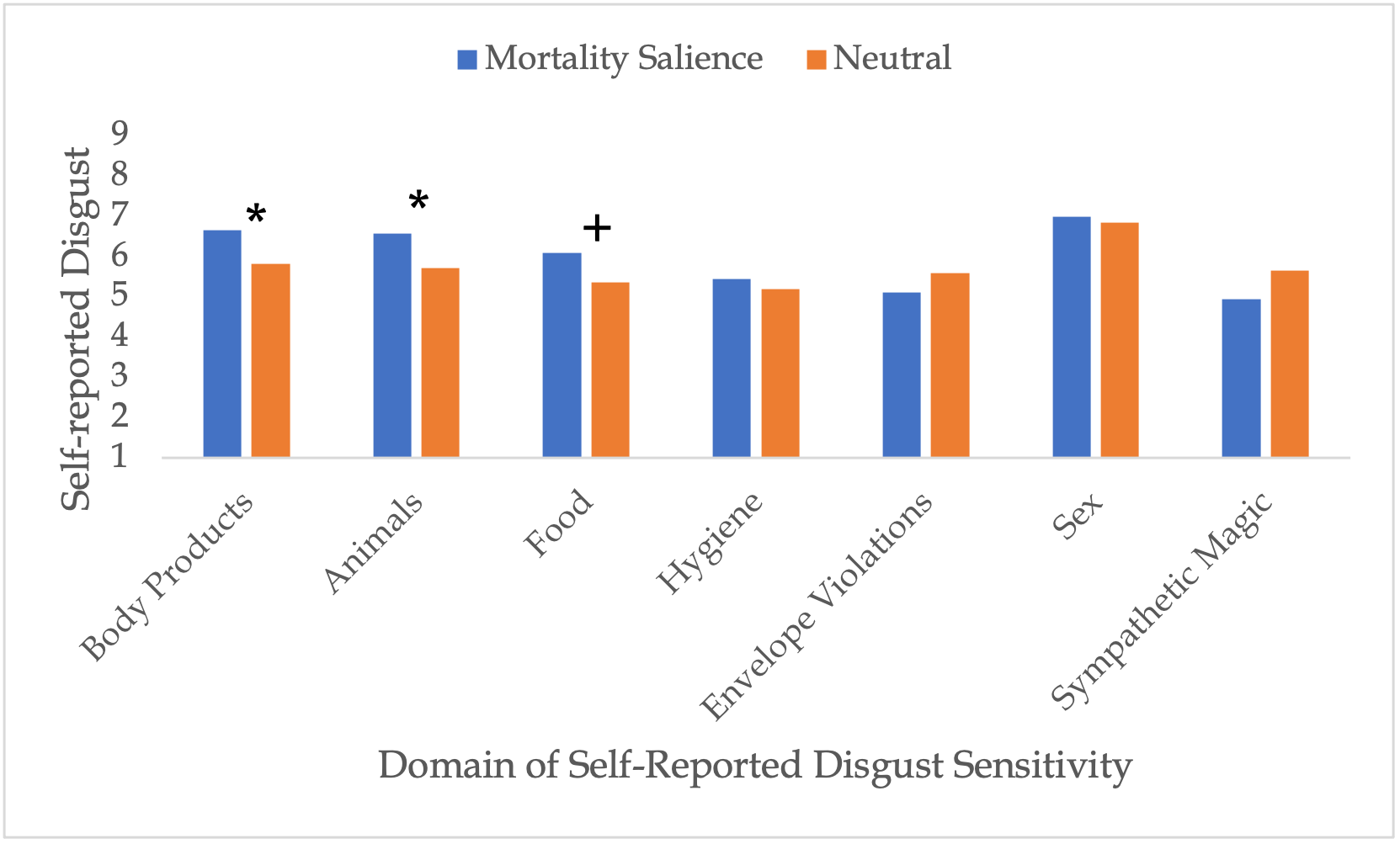

TMT emphasizes that humans are the only animals that have conscious thoughts and awareness of their own death. Extending TMT theory, Goldenberg et al. (2001) suggested that making death salient would elicit a disgust response in humans. In this study, participants were randomly assigned to either a control condition or a mortality salience condition. In the mortality salience condition, participants were asked to describe the emotions they experience when contemplating their own death and to describe what will happen to them after they die. Then, participants completed a disgust sensitivity measure. Participants who thoughts about their death reported more disgust in the domains of body products and animals; food-disgust approached significance (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Influence of Mortality Salience on Domains of Disgust Sensitivity

Adapted from “I am not an Animal: Mortality Salience, Disgust, and the Denial of Human Creatureliness,” by J.L. Goldenberg, T. Pyszczynski, J. Greenberg, S. Solomon, B. Kluck, and R. Cornwell, 2001, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(3), p. 431, (https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.427). Copyright 2001 by the American Psychological Association.

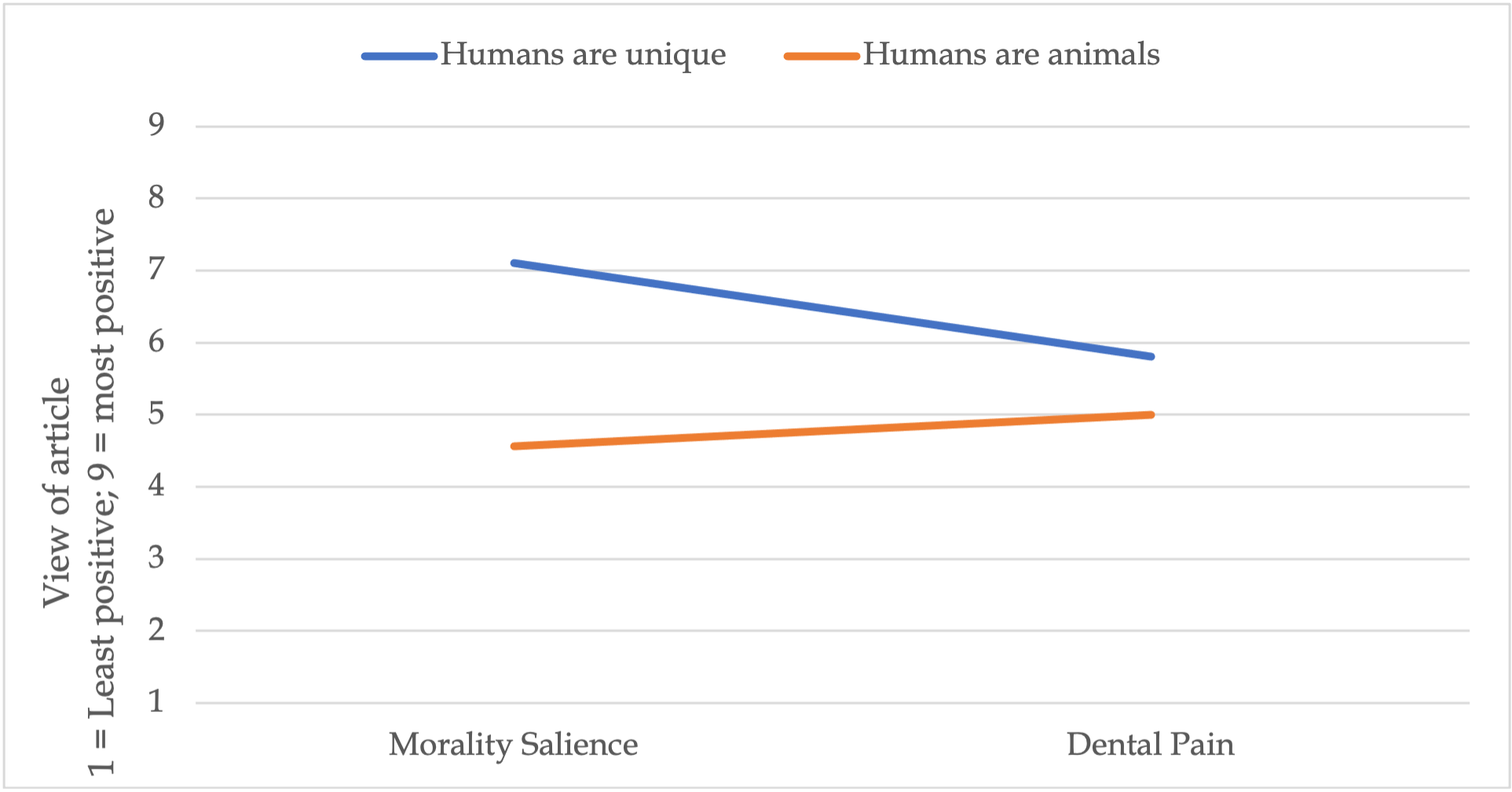

Figure 4

Self-related positivity of article as a function of morality prime and essay theme

Adapted from “I am not an Animal: Mortality Salience, Disgust, and the Denial of Human Creatureliness,” by J.L. Goldenberg, T. Pyszczynski, J. Greenberg, S. Solomon, B. Kluck, and R. Cornwell, 2001, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(3), p. 432, (https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.427). Copyright 2001 by the American Psychological Association.

Table 2

Death-related Dependent Variable Word Fragments

| Word Fragment | Possible Answers |

|---|---|

| D E _ _ | Dead or Deed |

| K I _ _ E D | Killed or Kissed |

| S K _ _ L | Skull or Skill |

| C O F F _ _ | Coffin or Coffee |

| G R A _ _ | Graver or Grape |

Adapted from “Disgust, Creatureliness and the Accessibility of Death‐related Thoughts,” by C.R. Cox, J.L. Goldenberg, T. Pyszczynski, and D. Weise, 2007, European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(3), p. 500, (https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.370). Copyright 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

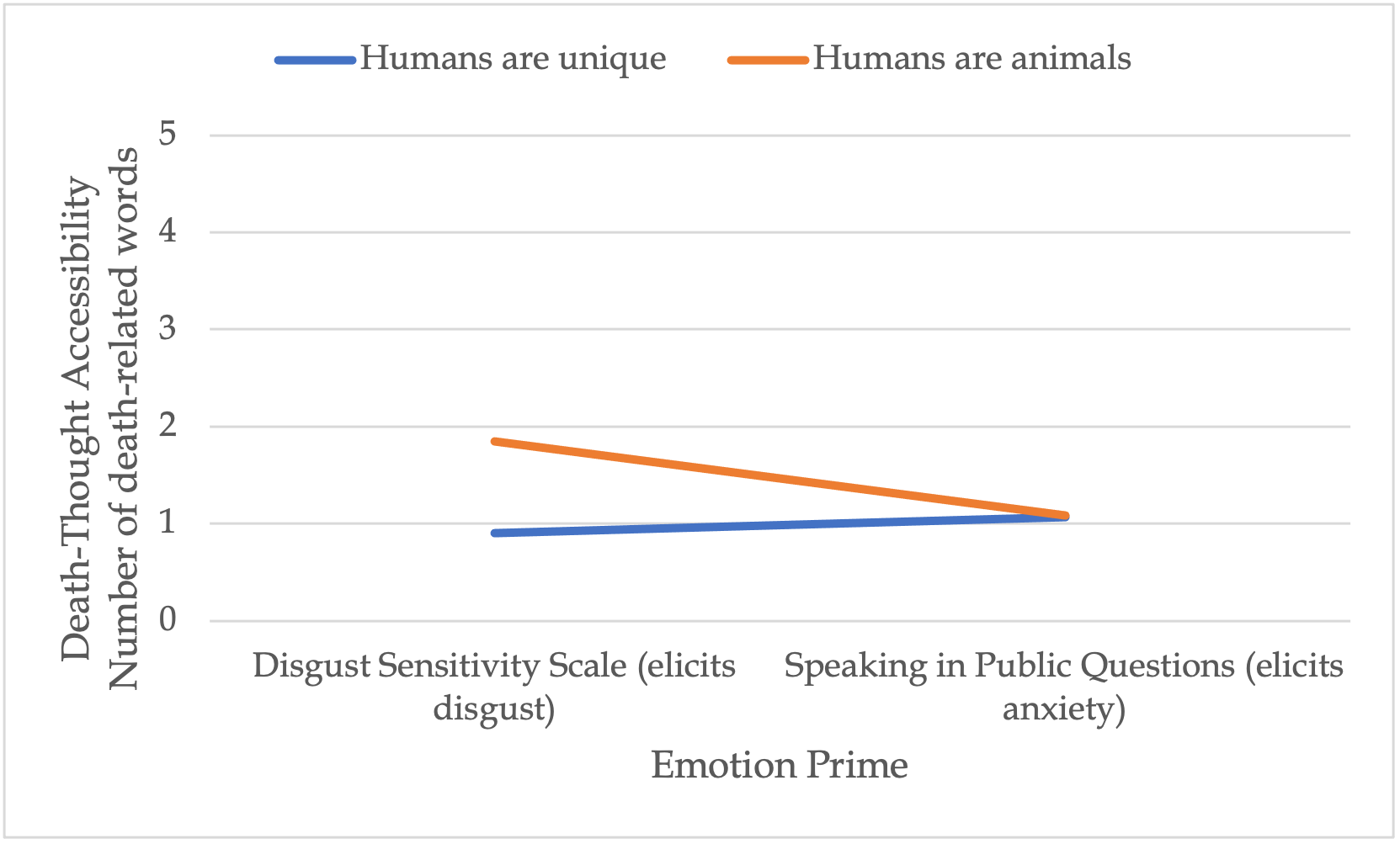

Figure 5

Number of death-related thoughts as a function of emotion prime and essay theme

Adapted from “Disgust, Creatureliness and the Accessibility of Death‐related Thoughts,” by C.R. Cox, J.L. Goldenberg, T. Pyszczynski, and D. Weise, 2007, European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(3), p. 503, (https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.370). Copyright 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.