Chapter 2: Classical Theories of Emotion

Schachter-Singer; Unexplained Arousal

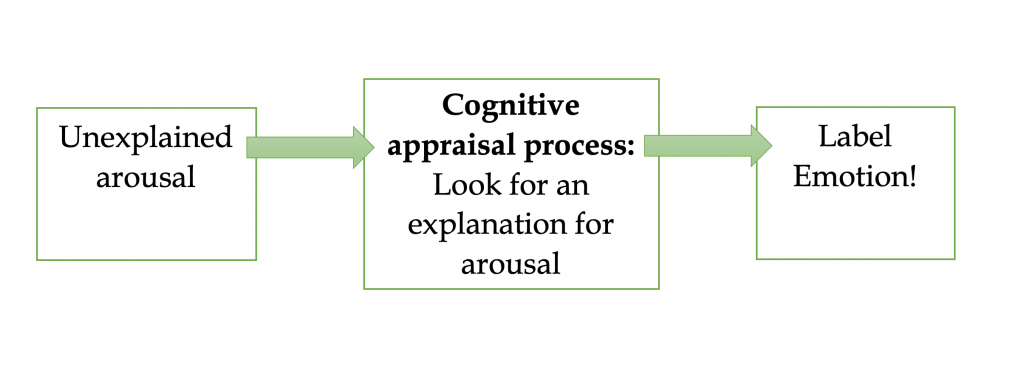

Schachter and Singer called changes in physiological arousal prior to cognitive appraisal processes unexplained arousal. Unexplained arousal is how intensely we experience an emotion before we label the emotion. It’s unexplained because the cognitive appraisal has not yet occurred. This concept suggests that we will not engage in cognitive appraisal unless we are experiencing physiological arousal first (see figure below). In their theory, unexplained arousal is important because often people identify the eliciting event incorrectly, and this causes them to mis-label their emotion experience. Schachter and Singer called this misattribution of arousal. Misattribution of arousal occurs when we pick the wrong attribution or explanation for our physiological change.

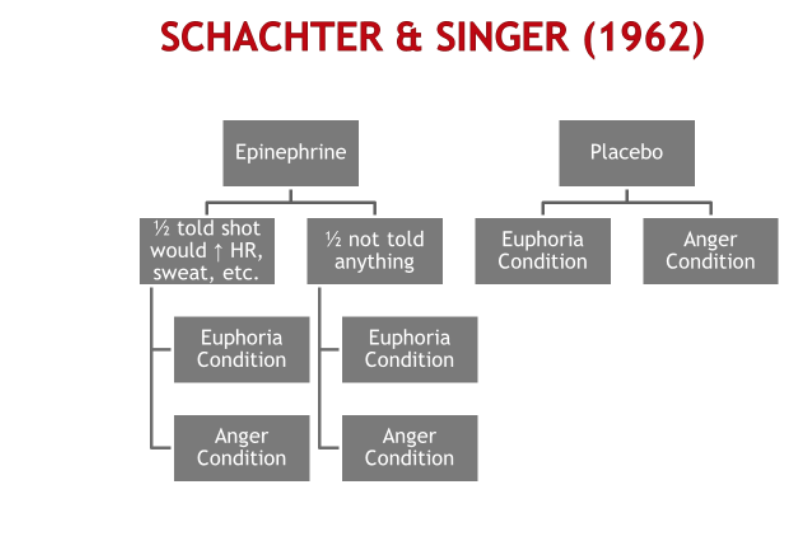

The more important results come from participants in the epinephrine condition.

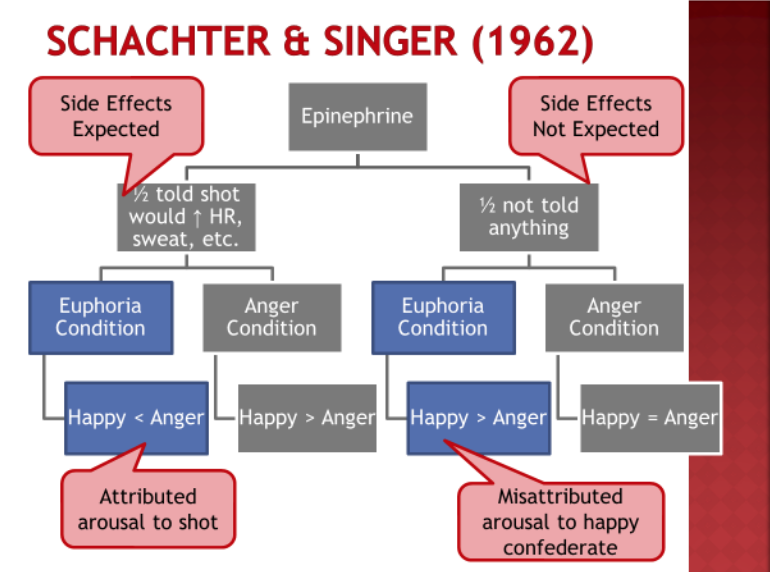

First, let’s compare participants in the euphoria condition (highlighted in blue in the figure below).

In the euphoria – side effects not expected group, participants reported more happiness than anger. Remember, participants in this group are experiencing physiological arousal, but since they do not know what was in the shot, they misattribute their arousal to the euphoric condition (the happy confederate), instead of attributing their arousal to the shot. Participants in this group might be thinking “My heart is beating. Why is my heart beating? Oh, it’s because of that happy participant! I must be happy,” and so they report more happiness than anger.

In the euphoria – side effects expected group, participants reported more anger than happiness. Now, participants in this group are also experiencing physiological arousal, but they were told the shot would increase their arousal. So, they correctly attribute their unexplained arousal to the shot, and not to the euphoric confederate. These participants might be thinking “My heart is beating because of the shot. So, my heart can’t be beating because of the happy confederate. So, I am not really happy” and they reported low levels of happiness.

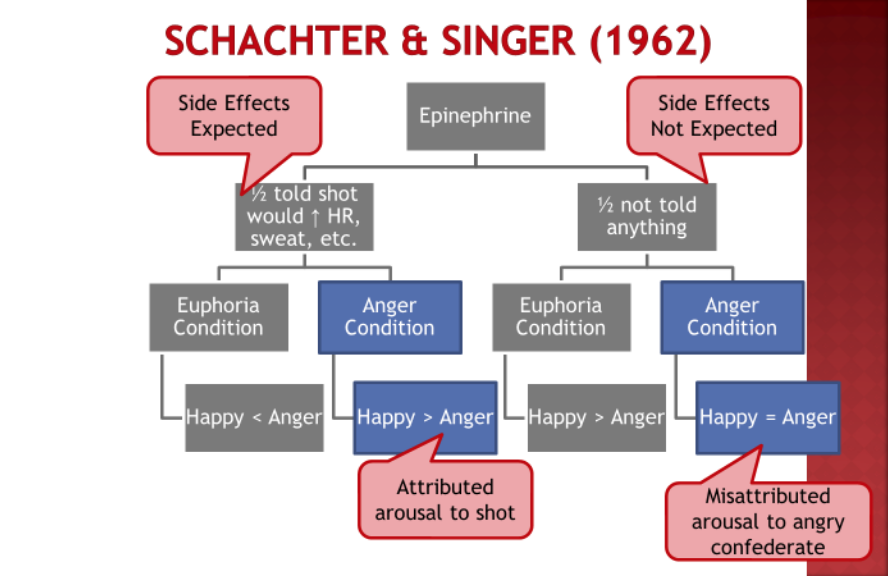

Now, let’s compare participants in the anger condition (highlighted in blue in the figure below)

In the anger – side effects not expected group, participants did not expect the shot to increase their arousal. So, they misattributed the side effects of the shot to the angry confederate. This group should have reported more anger than happiness, but they actually reported equal levels of anger and happiness. Participants in this group might be thinking “My heart is beating. Why is my heart beating? Oh, it’s because of that angry participant! I must be angry,” and they should have reported more anger than happiness.

In the anger – side effects expected group, participants did expect arousal to be caused by the shot. So, these participants correctly attributed their change in arousal to the shot and not to the angry confederate. These participants reported more happiness than anger because they were thinking “My heart is beating because of the shot. So, my heart can’t be beating because of the angry confederate. So, I am not really angry” and they reported low levels of anger.

Overall, Schachter and Singer’s (1962) study demonstrated that people can experience misattribution of arousal because their cognitive appraisals identified the wrong eliciting event (it’s the confederate, not the shot, that is causing my arousal!). Their work shows that emotion labels are determined by our interpretation of the situation and not by our physiological arousal. Further their work shows that when we experience physiological first, we then look to the situation to identify the cause of the arousal and to label our emotion. Finally, their theory shows that our environment includes several situational variables, and these variables may interrupt the cognitive appraisal process, such that the type of emotion people report changes.

Some criticisms of this early study exist. First, the ratio of happy : angry feelings is confusing. Today, we would measure happiness and anger as separate dimensions. Second, baseline measures of arousal were not included. Epinephrine could change people’s physiology in different amounts. This study focused on slow, cognitive appraisals – participants had the time to think about why they felt aroused and to consciously determine the emotion label. Today, we know that quick, automatic appraisal are important as well.